Mental Skills Training for Youth Experiencing Multiple Disadvantage

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Adversity, Stress, and Development in Youth

1.2. Need for Strengths-Based Approaches

1.2.1. Self-Determination Theory and Basic Psychological Needs

1.2.2. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy

1.2.3. Positive Youth Development

1.3. Summary

2. Mental Skills Training (MST)

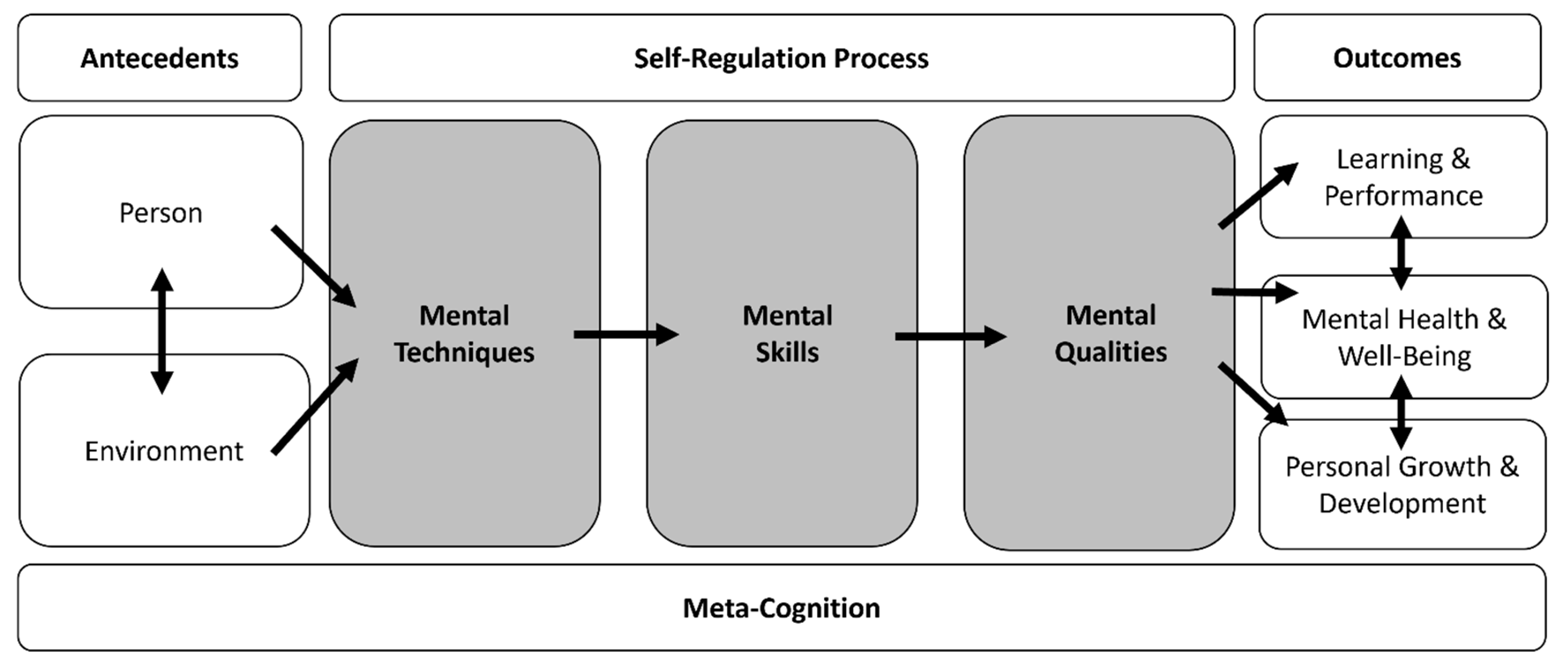

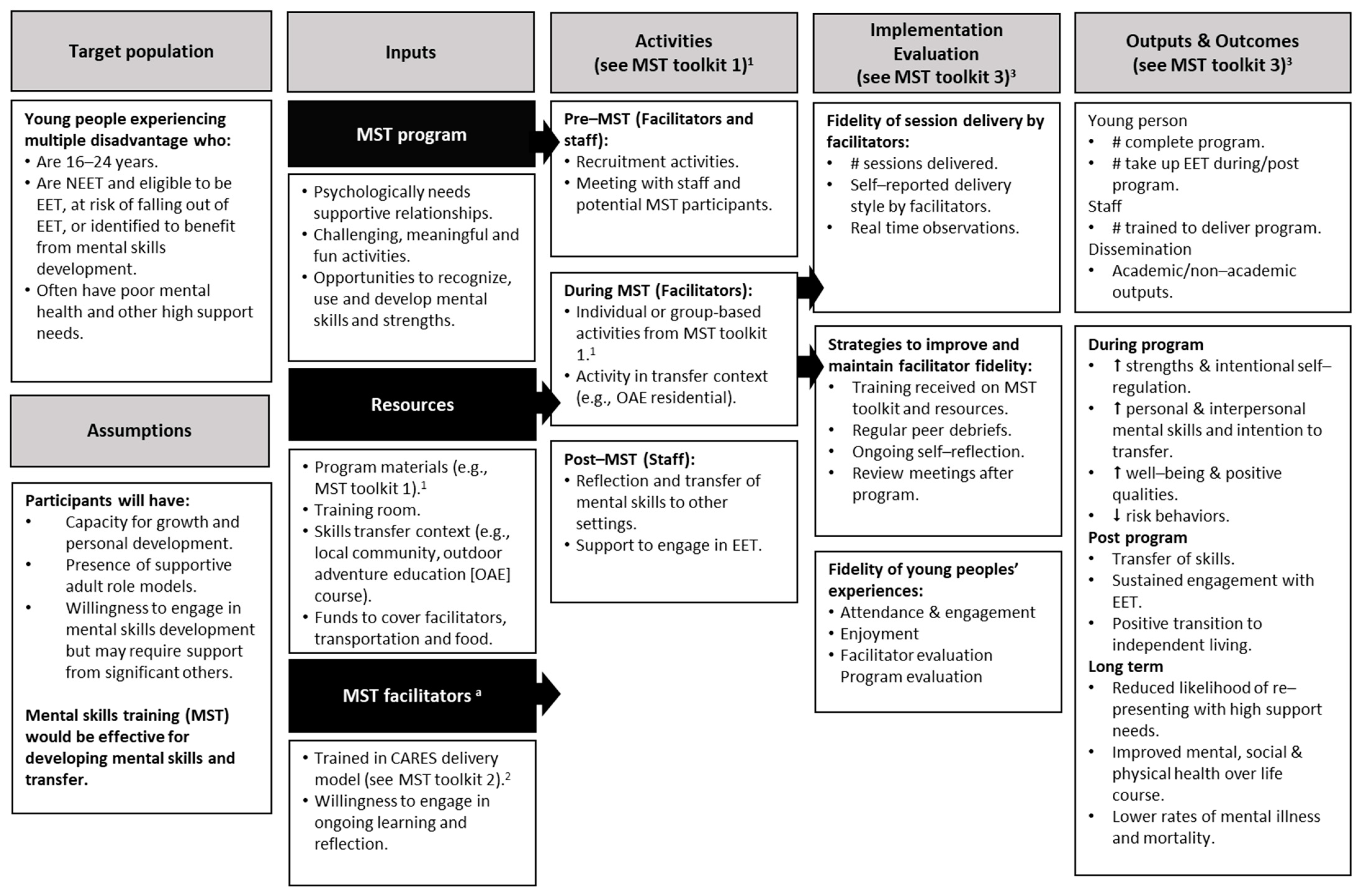

2.1. How MST Works

2.2. LifeMatters

2.3. My Strengths Training for Life™ (MST4Life™)

| Characteristics | LifeMatters | MST4Life™ |

|---|---|---|

| Yes [82,83,85] | Yes [37,71] |

| Unclear | Yes [11,37,71] |

| Unclear | Yes [39] |

| Yes [82] | Yes [37,89] |

| Yes [85] | Yes [37,94,97] |

| Unclear 1 | Yes [37,97] |

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreton, R.; Welford, J.; Collinson, B.; Greason, L.; Milner, C. Improving access to mental health services for those experiencing multiple disadvantage. Hous. Care Support. 2022, 25, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, R.D. Defining severe and multiple disadvantage from the inside: Perspectives of young people and of their support workers. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 1470–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, J.; Regan, S. Meeting Complex Needs: The Future of Social Care; IPPR: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, G.; Fitzpatrick, S. Hard Edges: Mapping Severe and Multiple Disadvantage; London, UK. 2015. Available online: https://e9a68owtza6.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Hard-Edges-Mapping-SMD-2015.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Moreton, R.; Welford, J.; Howe, P. Evaluation of Fulfilling Lives: Why We Need to Invest in Multiple Disadvantage. 2021. Available online: https://www.tnlcommunityfund.org.uk/media/insights/documents/Why-we-need-to-invest-in-multiple-disadvantage-2021.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Prince, D.M.; Rocha, A.; Nurius, P.S. Multiple disadvantage and discrimination: Implications for adolescent health and education. Soc. Work. Res. 2018, 42, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centrepoint Summary Report: The Youth Homeless Databank 2022–2023; London, UK. 2023. Available online: https://centrepoint.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-10/Centrepoint%20-%20Youth%20Homelessness%20Databank%202023%20Summary.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Homeless Link. We Have a Voice, Follow Our Lead: Young and Homeless 2020; Homeless Link: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Homeless Link. Young & Homeless 2018; Homeless Link: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, K.; Thompson, S.J.; McManus, H.; Lantry, J.; Flynn, P.M. Capacity for survival: Exploring strengths of homeless street youth. Child Youth Care Forum 2007, 36, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, S.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Holland, M.J.G.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. The experiences of homeless youth when using strengths profiling to identify their character strengths. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronley, C.; Evans, R. Studies of resilience among youth experiencing homelessness: A systematic review. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2017, 27, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevington, D.; Fuggle, P.; Fonagy, P. Applying attachment theory to effective practice with hard-to-reach youth: The AMBIT approach. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2015, 17, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, L.D.; Carroll, P.; Hamilton, W.K. Evaluation of an intervention promoting emotion regulation skills for adults with persisting distress due to adverse childhood experiences. Child. Abus. Negl. 2018, 79, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, K.; Murphy, D.; Everitt, G.; Tickle, A. Use of one-to-one psychotherapeutic interventions for people experiencing severe and multiple disadvantages: An evaluation of two regional pilot projects. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2022, 23, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.L.; Norton, E.S.; Mackey, A.P. A systematic review of interventions to ameliorate the impact of adversity on brain development. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 153, 105391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, M.D. How early life adversity transforms the learning brain. Mind Brain Educ. 2021, 15, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J.; Robbins, T.W. Decision-Making in the adolescent brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Choudhury, S. Development of the adolescent brain: Implications for executive function and social cognition. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindle, R.C.; Pearson, A.; Ginty, A.T. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) relate to blunted cardiovascular and cortisol reactivity to acute laboratory stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 134, 104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; COPACFH; COFCAKC; SODBP; Siegel, B.S.; Dobbins, M.I.; Earls, M.F.; Garner, A.S.; McGuinn, L.; et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Acad. Pediatr. 2009, 9, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, D.A.; Farah, M.J.; Meaney, M.J. Socioeconomic status and the brain: Mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.W.; Rosanbalm, K.; Christopoulos, C.; Hamoudi, A.; OPRE; ACF; HHS. Self-Regulation and Toxic Stress: Foundations for Understanding Self-Regulation from an Applied Developmental Perspective; Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease: Central links between stress and SES. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 190–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willingham, D.T. Ask the cognitive scientist: Why does family wealth affect learning? Am. Educ. 2012, 36, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Eldesouky, L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation goals: An individual difference perspective. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2019, 13, e12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Lerner, R.M. Positive development in adolescence: The development and role of intentional self-regulation. Hum. Dev. 2008, 51, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp-Paglicci, L.; Stewart, C.; Rowe, W. Can a self-regulation skills and cultural arts program promote positive outcomes in mental health symptoms and academic achievement for at-risk youth? J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2011, 37, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahranavard, S.; Miri, M.R.; Salehiniya, H. The relationship between self-regulation and educational performance in students. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, L.; Richardson, E.W.; Goetz, J.; Futris, T.G.; Gale, J.; DeMeester, K. Financial self-efficacy: Mediating the association between self-regulation and financial management behaviors. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2021, 32, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L.; Belsky, D.; Dickson, N.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Houts, R.; Poulton, R.; Roberts, B.W.; Ross, S. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 2693–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadsworth, M.E. Development of maladaptive coping: A functional adaptation to chronic, uncontrollable stress. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2015, 9, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Kim, P. Childhood poverty and young adults’ allostatic load: The mediating role of childhood cumulative risk exposure. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackie, P.; Thomas, I. Nations Apart? Experienced of Single Homeless People Across Great Britain; Crisis: London, UK, 2014; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, J.; Whiting, R.; Parry, B.J.; Clarke, F.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cooley, S.J.; Quinton, M.L. The My Strengths Training for Life program: Rationale, logic model, and description of a strengths-based intervention for young people experiencing homelessness. Eval. Program. Plan. 2022, 91, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Icenogle, G.; Shulman, E.P.; Breiner, K.; Chein, J.; Bacchini, D.; Chang, L.; Chaudhary, N.; Giunta, L.D.; Dodge, K.A.; et al. Around the world, adolescence is a time of heightened sensation seeking and immature self-regulation. Dev. Sci. 2018, 21, e12532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Holland, M.J.G.; Thompson, J.L.; Cumming, J. Improving outcomes in young people experiencing homelessness with My Strengths Training for Life (TM) (MST4Life (TM)): A qualitative realist evaluation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.R.; Shogren, K.A.; Wehmeyer, M.L. Supports and support needs in strengths-based models of intellectual disability. In Handbook of Research-Based Practices for Educating Students with Intellectual Disability, 1st ed.; Shogren, K.A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, A.; Filson, B.; Kennedy, A.; Collinson, L.; Gillard, S. A paradigm shift: Relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych Adv. 2018, 24, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magwood, O.; Leki, V.Y.; Kpade, V.; Saad, A.; Alkhateeb, Q.; Gebremeskel, A.; Rehman, A.; Hannigan, T.; Pinto, N.; Sun, A.H. Common trust and personal safety issues: A systematic review on the acceptability of health and social interventions for persons with lived experience of homelessness. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caiels, J.; Milne, A.; Beadle-Brown, J. Strengths-based approaches in social work and social care: Reviewing the evidence. J. Long. Term. Care 2021, 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, W.; Lovell, M.; Langenberg, J.; Heron, M. Deficit Discourse and Strengths-Based Approaches: Changing the Narratives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Health and Wellbeing; Melbourne, Australia. 2018. Available online: https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/deficit-discourse-strengths-based.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Caiels, J.; Silarova, B.; Milne, A.J.; Beadle-Brown, J. Strengths-based approaches: Perspectives from practitioners. Br. J. Soc. Work 2024, 54, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, C.A.; Saleebey, D.; Sullivan, W.P. The future of strengths-based social work. Adv. Soc. Work. Spec. Issue Futures Soc. Work 2006, 6, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.; Ziglio, E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model. Promot. Educ. 2007, 14, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M. The positive youth development perspective: Theoretical and empirical bases of strengths-based approach to adolescent development. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology, 2nd ed.; Lopez, S.J., Snyder, C.R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J.G.; Cadell, S. Power, pathological worldviews, and the strengths perspective in social work. Fam. Soc. 2009, 90, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scerra, N. Strengths-based practices: An overview of the evidence. Dev. Pract. Child. Youth Fam. Work. J. 2012, 31, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, C.A.; Shapiro, V.B.; Accomazzo, S.; Manthey, T.J. Strengths-based social work: A meta-theory to guide social work research and practice. In Theoretical Perspectives for Direct Social Work Practice, 3rd ed.; Coady, N., Lehmann, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Bosch, J.A.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. Self-determination theory and diminished functioning: The role of interpersonal control and psychological need thwarting. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1459–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination research: Reflections and future directions. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, C.; Ding, X.; Kim, J.; Zhang, A.; Hai, A.H.; Jones, K.; Nachbaur, M.; O’Connor, A. Solution-focused brief therapy in community-based services: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2024, 34, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, S. The applicability of two strengths-based systemic psychotherapy models for young people following Type 1 Trauma. Child. Care Pract. 2014, 20, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, J.; Guse, T. A solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) intervention model to facilitate hope and subjective well-being among trauma survivors. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2021, 51, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, H.; George, E.; Iveson, C. Solution Focused Brief Therapy: 100 Key Points and Techniques; Routledge: Hove, East Sussex, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- de Shazer, S.; Dolan, Y.; Korman, H.; Trepper, T.; McCollum, E.; Kim Berg, I. More than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Gestsdóttir, S.; Urban, J.B.; Bowers, E.P.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Intentional self-regulation, ecological assets, and thriving in adolescence: A developmental systems model. New Dir. Child. Adolesc. Dev. 2011, 2011, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdóttir, S.; Geldhof, G.J.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. What drives positive youth development? Assessing intentional self-regulation as a central adolescent asset. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2017, 11, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, C.M.; Bowers, E.P.; Gestsdóttir, S.; Chase, P.A. The development of intentional self-regulation in adolescence: Describing, explaining, and optimizing its link to positive youth development. In Advances in Child Development and Behavior; Lerner, R.M., Lerner, J.V., Benson, J.B., Eds.; JAI: Stamford, CT, USA, 2011; Volume 41, pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tidmarsh, G.; Thompson, J.L.; Quinton, M.L.; Cumming, J. Process evaluations of positive youth development programmes for disadvantaged young people: A systematic review. J. Youth Dev. 2022, 17, 106–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vealey, R. Future directions in psychological skills training. Sport. Psychol. 1998, 2, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlick, T. Pursuit of Excellence, 5th ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Estanol, E.; Shepherd, C.; MacDonald, T. Mental skills as protective sttributes against eating disorder risk in dancers. J. Appl. Sport. Psychol. 2013, 25, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golby, J.; Wood, P. The effects of psychological skills training on mental toughness and psychological well-being of student-athletes. Psychology 2016, 7, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.J.; Forneris, T.; Wallace, I. Sport-based life skills programming in the schools. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2005, 21, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, L.-A.; Woodcock, C.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cumming, J.; Duda, J.L. A qualitative evaluation of the effectiveness of a mental skills training program for youth athletes. Sport. Psychol. 2013, 27, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, J.; Clarke, F.J.; Holland, M.J.G.; Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.L.; Cooley, S.J. A feasibility study of the My Strengths Training for Life™ (MST4Life™) Program for young people experiencing homelessness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, M.J.G.; Cooley, S.J.; Cumming, J. Understanding and assessing young athletes’ psychological needs. In Sport Psychology for Young Athletes, 1st ed.; Knight, C.J., Harwood, C.G., Gould, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan, S.J. LifeMatters: Using physical activities and games to enhance the self-concept and well-being of disadvantaged youth. In Positive Psychology in Sport and Physical Activity, 1st ed.; Brady, A., Grenville-Cleave, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R. Thinking about thinking: Developing metacognition in children. Early Child. Dev. Care 1998, 141, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, M.J.; Woodcock, C.; Cumming, J.; Duda, J.L. Mental qualities and employed mental techniques of young elite team sport athletes. J. Clin. Sport. Psychol. 2010, 4, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vealey, R. Mental skills training in sport. In Handbook of Sport Psychology, 3rd ed.; Tenenbaum, G., Eklund, R., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2007; pp. 287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan, S.J. Using games to enhance life satisfaction and self-worth of orphans, teenagers living in poverty, and ex-gang members in Latin America. In Case Studies in Sport Development: Contemporary Stories Promoting Health, Peace and Social Justice; Schinke, R.J., Lidor, R., Eds.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2013; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Almerigi, J.B.; Theokas, C.; Phelps, E.; Gestsdóttir, S.; Naudeau, S.; Jelicic, H.; Alberts, A.; Ma, L.; et al. Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, S.J.; Francke Ramm, M.D.L. Improving life satisfaction, self-concept, and happiness of former gang members using games and psychological skills training. J. Sport. Dev. 2015, 3, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, R.F.; Skinner, M.L.; Alvarado, G.; Kapungu, C.; Reavley, N.; Patton, G.C.; Jessee, C.; Plaut, D.; Moss, C.; Bennett, K.; et al. Positive youth development programs in low- and middle-income countries: A conceptual framework and systematic review of efficacy. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.G.; Hanrahan, S.J. Life Matters: Exploring the influence of games and mental skills on relatedness and social anxiety levels in disengaged adolescent students. J. Appl. Sport. Psychol. 2019, 32, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanrahan, S.J.; Tshube, T. Developing Batswana coaches’ competencies through the LifeMatters programme: Teaching mental skills through games. Botsw. Notes Rec. 2018, 50, 189–198. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/90026908 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Page, D.; Hanrahan, S.; Buckley, L. Positive youth development program for adolescents with disabilities: A pragmatic trial. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2024, 71, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.T.; Hanrahan, S.; Buckley, L. Real-world trial of positive youth development program “LifeMatters” with South African adolescents in a low-resource setting. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 146, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, L.; Kjeldsted, E.; Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Bentsen, P. Mental, physical and social health benefits of immersive nature-experience for children and adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment of the evidence. Health Place 2019, 58, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Macmillian: New York, NY, USA, 1963. (Original work published 1938). [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, M.L.; Tidmarsh, G.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. A Kirkpatrick model process evaluation of reactions and learning from my strengths training for life™. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 11320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.; Cumming, J. Mental Skills Training Toolkit: A Resource for Strengths-Based Development; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, M.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. Mental Skills Training Toolkit: Ensuring Psychologically Informed Delivery; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, F.J.; Parry, B.J.; Quinton, M.; Cumming, J. Mental Skills Training Commissioning and Evaluation Toolkit: Improving Outcomes in Young People Experiencing Homelessness; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lethem, J. Brief Solution Focused Therapy. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2002, 7, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidmarsh, G.; Whiting, R.; Thompson, J.L.; Cumming, J. Assessing the fidelity of delivery style of a mental skills training programme for young people experiencing homelessness. Eval. Program. Plan. 2022, 94, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, B.J.; Thompson, J.L.; Holland, M.J.G.; Cumming, J. Promoting personal growth in young people experiencing homelessness through an outdoors-based program. J. Youth Dev. 2021, 16, 157–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, M.L.; Clarke, F.J.; Parry, B.J.; Cumming, J. An evaluation of My Strengths Training for Life for improving resilience and well-being of young people experiencing homelessness. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidmarsh, G.; Thompson, J.L.; Quinton, M.L.; Parry, B.J.; Cooley, S.J.; Cumming, J. A platform for youth voice in MST4Life: A vital component of process evaluations. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 17, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, L.; Siu, J. Outcome and Economic Evaluation of the My Strengths Training for Life™ Programme with St Basils; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Page, D.T. The LifeMatters Program Implemented in South Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Bowers, E.P.; Boyd, M.J.; Mueller, M.K.; Napolitano, C.M.; Schmid, K.L.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Creation of short and very short measures of the Five Cs of Positive Youth Development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Martin-Barrado, A.D.; Muñoz-Parralo, M.; Roh, M.; Garcia-Moro, F.J.; Mendoza-Berjano, R. The 5Cs of positive youth development and risk behaviors in a sample of spanish emerging adults: A partial mediation analysis of gender differences. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 2410–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Kirkpatrick, W. An Introduction to the New World Kirkpatrick Model. Available online: https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Introduction-to-The-New-World-Kirkpatrick%C2%AE-Model.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Sukhera, J. Narrative reviews: Flexible, rigorous, and practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larter, N.; Jersky, M.; Ryan, L.; Harding, G.; Moore, M.; Hamill, L.; Caplice, S.; Woolfenden, S.; Zwi, K. Strength-Based Approaches to Providing an Aboriginal Community Child Health Service. Int. J. Indig. Health 2024, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mental techniques | Cognitive or behavioral techniques used to build mental skills and qualities [72]. | Action planning Goal setting Positive self-talk Support seeking |

| Mental skills | The capacity to intentionally self-regulate thoughts, emotions, and behaviors [72]. | Focusing attention Handling pressure Self-awareness Self-control |

| Mental qualities | Positive intrapersonal and/or interpersonal characteristics displayed by or within an individual [72]. | Intrinsic motivation Resilience Self-confidence Self-worth |

| Mental skills transfer | The application of mental skills developed in one context and then applied to a new one. | Learning positive self-talk from support worker and then using positive self-talk before a job interview. |

| Mental skills training | The systematic development, application, and implementation of mental techniques for developing mental skills to promote the mental qualities needed for well-being and optimal development [37,72]. | LifeMatters [73] MST4Life™ [37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cumming, J.; Quinton, M.L.; Tidmarsh, G.; Reynard, S. Mental Skills Training for Youth Experiencing Multiple Disadvantage. Youth 2024, 4, 1591-1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040102

Cumming J, Quinton ML, Tidmarsh G, Reynard S. Mental Skills Training for Youth Experiencing Multiple Disadvantage. Youth. 2024; 4(4):1591-1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040102

Chicago/Turabian StyleCumming, Jennifer, Mary L. Quinton, Grace Tidmarsh, and Sally Reynard. 2024. "Mental Skills Training for Youth Experiencing Multiple Disadvantage" Youth 4, no. 4: 1591-1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040102

APA StyleCumming, J., Quinton, M. L., Tidmarsh, G., & Reynard, S. (2024). Mental Skills Training for Youth Experiencing Multiple Disadvantage. Youth, 4(4), 1591-1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4040102