Community-Based Alternatives to Secure Care for Seriously At-Risk Children and Young People: Learning from Scotland, The Netherlands, Canada and Hawaii

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Secure Care, Community-Based Alternative Models of Care, and Cohort—Definitions, Practice and Research

2.1. Secure Care

Regrettably, three decades of research into the effectiveness of compulsory treatment have yielded a mixed, inconsistent, and inconclusive pattern of results, calling into question the evidence-based claims made by numerous researchers that compulsory treatment is effective in the rehabilitation of substance users.

2.2. Alternatives to Secure Care

The challenge for society is to provide the kind of structure, safety and quality of care that these [secure care] facilities provide without depriving young people of their liberty and of the opportunity to develop into individuals who can cope with freedom.

2.3. Profile of the Children Admitted to Secure Care

3. Materials and Methods

- Background: What is/are a jurisdiction’s model/s of secure care? What is the evidence to support its effectiveness? What were the enablers for reform—what is the context, how did the alternative to secure care come about?

- Service: What is the alternatives to secure care model? Who delivers it?

- Efficacy: Is there any evidence of effectiveness of the alternatives to secure care?

- Challenges: What are the primary challenges relating to alternatives to secure care?

- Hawaii has a First Nations population and has a bifurcated youth justice and child protection system. Hawaii offers a unique, culturally grounded, evidence-based alternative model of care, characterised by self-determination and responding to the needs of traumatised youth. Hawaii also has two non-secure models for responding to sexual exploitation.

- Canada (Alberta) has a First Nations population and a bifurcated youth justice and child protection system. It has secure care that is also a short-term crisis intervention, similar to the Victoria/Western Australian models of secure care. Canada (Alberta) offers a comprehensive spectrum of intensive specialist interventions surrounding and diverting from secure care within a mental health framework.

- The Netherlands has a bifurcated youth justice and child protection system with a very similar timeline as to why and when this occurred. The Netherlands demonstrates how powerful the voice of lived experience of secure care can be in driving reform. The Netherlands have committed to using virtually no secure care by 2030 and demonstrated how providers of secure care can quickly evolve to open models of care focusing on outreach and multidisciplinary alternatives.

- Scotland has introduced the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Act 2024, which ended the placement of under 18-year-olds in Young Offenders Institutions and raised the age of referral to the Children’s Hearings System to include all 16- and 17-year-olds. The future model of secure care is being considered in light of these reforms. Scotland offers models of intensive community-based support. The alternatives to secure care are the culmination of system-wide reform and reflect strong research partnerships and a rights-based approach.

- Findings are primarily based on qualitative data provided by system experts. Due to the highly politically sensitive nature of secure care and reluctance of jurisdictions to share quantitative data, only a limited amount of quantitative data was available.

- No outcomes or comparative data (between secure care and alternatives) were evident and/or made available by any jurisdiction.

- International case study data are limited in scope to the representative meetings and sites visited in the countries of Hawaii, Canada, The Netherlands and Scotland.

- Case studies were, in part, chosen by the researcher, who has experience predominately specific to the state of Victoria, Australia. Further analysis will need to be completed to determine applicability to other jurisdictional contexts.

4. Results

4.1. Alternatives to Secure Care in Scotland

- Case Study 1. Glasgow City Council community-based intensive services.

| Background: Informed by the Independent Care Review [9] and the promise, Glasgow City Council have developed a suit of intensive services and continued care up until the age of 26, with a corresponding Family Support Strategy. Glasgow City Council’s intensive services are enabled by the local authorities’ collective leaderships’ willingness to hold risk in the community. It is based on the belief that secure care provides system relief rather than being driven by children’s outcomes. Glasgow City Council have a Secure Screening Group with representation from mental health, education, residential care and Alcohol and Other Drugs providers. The Secure Screening Group was initially developed to determine who met the criteria for secure care and make referrals to intensive services when possible as a direct, immediate, bespoke wraparound support, as opposed to a secure care admission. The scope of the group later expanded to also consider young people on the edge of a secure care intervention. As such, the Secure Screening Group divert away from secure care to intensive services when appropriate. Service Intensive Services: The suite of intensive services include the following (with additional information on some interventions in the following, and a spotlight on ISMS):

Initial pilot funding of ISMS helped introduce a new mindset in Scotland regarding the use of alternatives to secure care. There is also evidence to suggest it is an effective alternative to secure care (e.g., Glasgow City Council ISMS evaluation, detailed below). However, there has been inconsistent availability and implementation across Scotland. Intensive Monitoring and Support Service Education: Provide education directly to young people (3 × 1.5 h sessions) in conjunction with school and Interrupted Learners Services. They also bring together the three education providers and coordinate service delivery. There is consideration that this service converts to education facilitation rather than education provision. Outdoor Resource Centre: A highly flexible, creative method of responding to crisis. Support is provided by 8 trauma-trained staff who can work 1:1 with children up to 25 h a week for a long period of time (e.g., 2–3 years). Staff work alongside other intensive supports. Support varies significantly depending on the children’s interests and can include boat trips or weekends away. Glasgow Intensive Family Support Service: Support service for families going through tough times with children at risk of being placed elsewhere. About 50% of the Glasgow Intensive Family Support Services provide placement support (e.g., in foster care), with a particular focus on support in kinship arrangements so the child can return to the family. Effectiveness Glasgow City Council attribute their intensive services to dramatic reductions in their rates of child removal and use of residential care, which they believe has led to a significantly reduced demand on secure care. Based on the cost of secure care (approximately GBP 6500 a week) and intensive services (approximately GBP 2000 a week), it is believed that for approximately every 30 children, Glasgow City Council are saving about 10.4 million pounds. The evaluation of ISMS found that ‘evidence from the case studies and local evaluation and monitoring work indicate that the ISMS and intensive support service programmes have been effective for … improved attendance rates on programmes, reducing absconding and reducing substance misuse. There is particularly wide support for the intensive support provision’. Glasgow City Council have also reported:

|

4.2. Alternatives to Secure Care—The Netherlands

- Case Study 2. Een thuis voor noordje—Bovenregionaal Expertisenetwerk Jeugd Noord-Holland (bennh.nl)

| Background: Thuis voor Noordje is a cooperation in the north of Noord Holland (province), which came together with a shared commitment to no longer provide secure care. This cooperation has brought together those responsible for care provision and governance to support children and young people in North Holland who are threatened in their development by complex problems or situations. Parlan is the care provider in this cooperation [59]. Thuis voor Noordje covers a large geographical area with approximately a 2 million population. Parlan previously delivered a large 80-bed closed care facility with restrictive practices. The average length of stay was six months. Young people admitted to closed youth care had high levels of placement breakdown and/or movement (averaging 8–10 placements) between open residential care and secure residential care. As such, Thuis voor Noordje see housing stability as core to their reform agenda of closed youth care. As the result of funding changes, including the decentralisation of services to local municipalities, in 2018 it became clear to Parlan that its large-scale closed youth care was no longer financially viable. Parlan believe this financial crisis provided an opportunity for reform. It prompted the establishment of Thuis voor Noordje and what they described as a moral decision to no longer provide closed youth care. Service: The following three elements form the crux of Parlan’s alternative service delivery response:

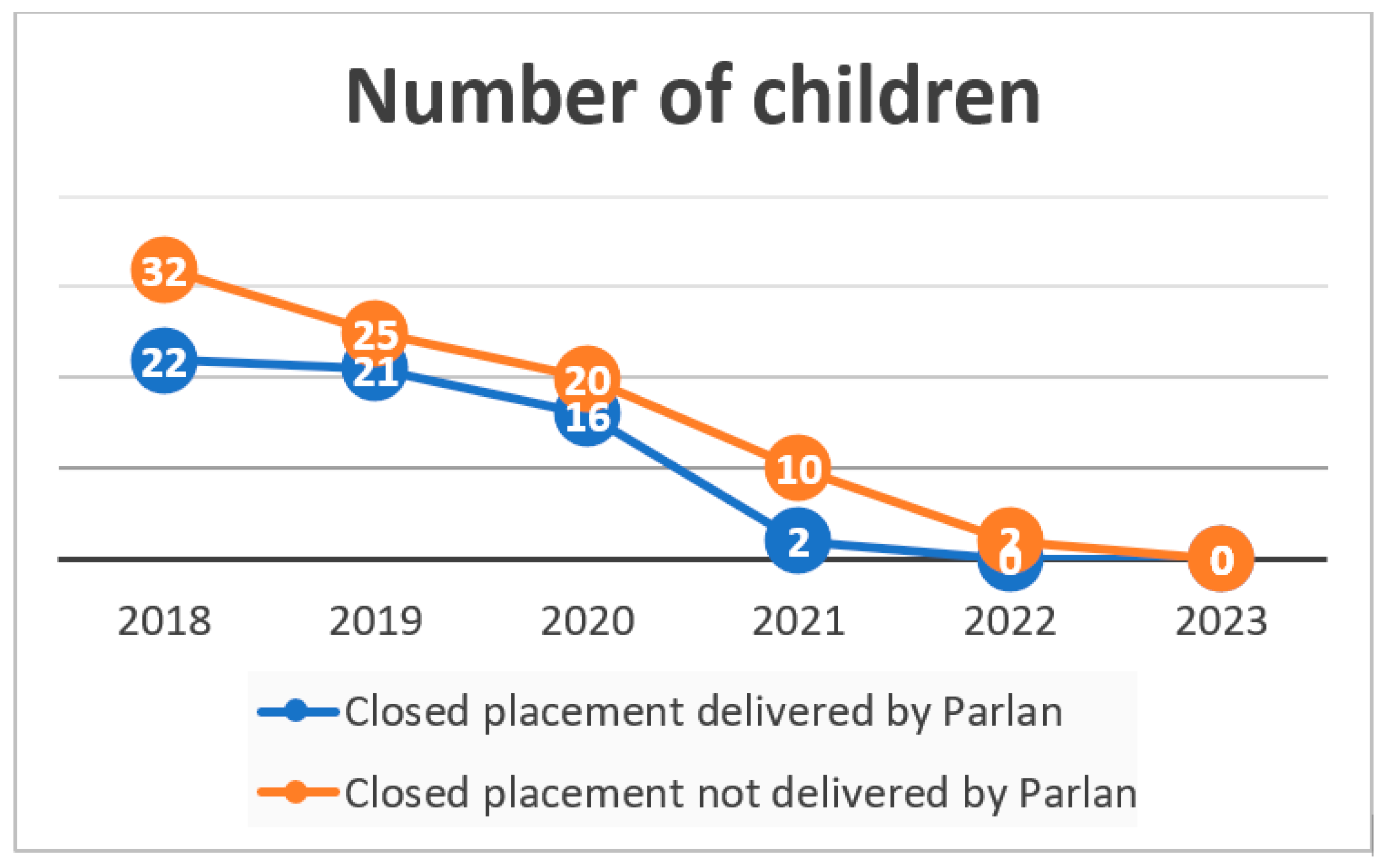

The residential care offered is intended to provide housing stability and, as such, there is no time period allocated. Parlan currently have two, four- to six-bed (three ‘in-house’ and three independent living units linked to housing for the older/transitioning cohort) centrally located mixed-gender houses, with 24/7 wraparound support and high staff ratios. Young people are supported to engage with nearby generalist education. There are no restrictive practices or cameras—a harm reduction approach and relational security are utilised. Effectiveness: Thuis voor Noordje believe the key to the success of their reform agenda is that their vision/commitment to no longer provide closed youth care is shared by all key stakeholders, across all levels of government (e.g., local municipalities and councils), secondary education partnerships and youth care providers. Ending the use of closed youth care reflected a shared cultural change to the conceptualisation and response to risk—in line with values/principles of all areas/sectors. Saying ‘no’ to a closed youth care response has meant a lot of crisis management in the community and supporting stakeholders through this time. Parlan initially converted their closed youth care to a combination of closed and open residential care; however, it quickly became clear once alternatives were in place that they could convert all closed placements to open placements. The below Figure 1 clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of their alternative service provision in ending the use of closed youth care. The process of closed youth care reform commenced in 2020, and the area now generally has no closed youth care admissions. Challenges Parlan identified the following challenges associated with the implementation of their alternative service provision model:

|

5. Alternatives to Secure Care—Canada (Alberta)

- Case Study 3. Acute@Home (Wood’s Homes)

| Background: In 2018, Wood’s Homes partnered with the Alberta Children’s Hospital—Psychiatric Emergency Services—to provide immediate, in-home support, advocacy and system navigation for young people and their families/carers. The aim is to provide a continuum of mental health care through short-term support, which will keep a child at home when there is no imminent risk but the child or young person is:

The Acute@Home team includes five family support counsellors, a team leader and psychiatric and nursing support from the hospital. The top-five presenting disorders they respond to are:

Through safety planning, psychoeducation, facilitating referrals and building family connections, Acute@Home supports families in developing the tools to prevent further escalation and establish stability. This program offers one to three sessions that take place with the family over the course of six to eight weeks to help mitigate the need for further hospital presentations. Clients are referred to the Acute@Home program by Alberta Children’s Hospital Emergency Department following a mental health assessment. Once the child is referred, the Acute@Home team will contact the family/carer within 72 h to discuss the child’s needs. The Acute@Home program provides:

The hard-copy factsheet for Acute@Home stated that the outcomes of Acute@Home include:

This intervention primarily supports community (as opposed to children on child protection orders) clients at risk of a mental health inpatient admission; however, it could be adapted to support transitions from secure care facilities. |

Alternatives to Secure Care—Hawaii

- Case Study 4. Kawailoa Youth and Family Wellness Center.

Background:

|

6. Discussion

- Community-based multi-agency intensive support, i.e., holistic, multi-systems and bespoke.

- Intensive specialist services, i.e., alternative care or community-based targeted specialist interventions, such as mental health, sexual exploitation, disability or sexualised behaviours.

- Diversionary and/or transitional support, i.e., alternative non-secure interventions built into a model of secure care service provision, including outreach, support after discharge and transitional housing.

- Secure care was placed within the scope of broader system-wide reform, and there was a systems emphasis on alternative service provision and pathways from secure interventions.

- There was an interrogation of the need for and minimising/eliminating the use of restrictive practices relating to children and ensuring that legislation, oversight and practice relating to restrictive practices are consistent across disciplines (mental health, youth justice, disability and secure care).

- Analysis of children’s pathways into secure care to identify and rectify service delivery gaps and/or blockers to service accessibility was completed.

- Insight was gained from children and young people with lived experience of secure care, listening to their views and placing them at the forefront of reform and ongoing policy decisions.

- All available legal protections were in place to adequately protect children’s rights.

- Multidisciplinary approaches to secure care and alternatives were enabled.

- Can risk be better managed in non-secure alternatives than secure care?

- Can alternatives lead to better outcomes than secure care?

- How can outcomes be best measured?

- What elements made alternative interventions effective in response to what cohorts need?

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nowak, M. United Nations Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty. 2019. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/treaty-bodies/crc/united-nations-global-study-children-deprived-liberty (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Stefanovic, L. Ending Deprivation of Liberty of Children, Institutions: A Review of Promising Practice. 2022. Available online: https://omnibook.com/view/b72aef58-a6c6-4727-92f6-11e87e83ca31/page/2 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Corr, M.-L.; Hanna, A. Children’s lives in Jersey—Secure Accommodation Orders. Internal CONFIDENTIAL Report. 2022. Available online: https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/publications/childrens-lives-in-jersey-secure-accommodation-orders-internal-co (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Enell, S.; Wilińska, M. Negotiating, opposing, and transposing dangerousness: A relational perspective on young people’s experiences of secure care. Young 2001, 29, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, A.; Prieur, A. ‘So, Why Am I Here?’ Ambiguous Practices of Protection, Treatment and Punishment in Danish Secure Institutions for Youth. Br. J. Criminol. 2019, 200, 1161–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andow, C. ‘Am I supposed to be in a prison or a mental hospital?’ The nature and purpose of secure children’s homes. Child. Soc. 2024; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Barclay, A.; Hunter, L.; Kendrick, A.; Malloch, M.; Hill, M.; McIvor, G. Secure Accommodation in Scotland: Its Role and Relationship with ‘Alternative Services’; Scottish Executive Education Department: Livingston, UK, 2005; Available online: https://www.sccjr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/Secure_Accommodation_in_Scotland.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Brogi, L.; Bagley, C. Abusing victims: Detention of child sexual abuse victims in secure accommodation. Child Abus. Rev. J. Br. Assoc. Study Prev. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 7, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Independent Care Review. The Promise. 2020. Available online: https://www.carereview.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/The-Promise.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- O’Brien, D.; Hudson-Breen, R. Grasping at straws, experiences of Canadian parents using involuntary stabilization for a youth’s substance use. Int. J. Drug Policy 2023, 117, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorian Department of Human Services. Placement in Secure Welfare Services. Child Protection Practice Manual. 2024. Available online: https://www.cpmanual.vic.gov.au/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Western Australia Department for Child Protection. Kath French Secure Care Centre Practice Guidelines. Government of Western Australia. 2011. Available online: https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-communities/casework-practice-manual#article/337-secure-care-arrangements (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Williams, A.; Wood, S.; Warner, N.; Cummings, A.; Hodges, H.; El-Banna, A.; Daher, S. Unlocking the Facts: Young People Referred To Secure Children’s Homes. 2020. Available online: https://whatworks-csc.org.uk/research-report/unlocking-the-facts-young-people-referred-to-secure-childrens-homes/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Care Inspectorate—Scotland. Position Paper—Depriving and Restricting Liberty for Children and Young People in Care Home, School Care and Secure Accommodation Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.careinspectorate.com/images/documents/Depriving_and_restricting_liberty_for_children_and_young_people_in_care_home_school_care_and_secure_accommodation_services.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Crowe, K. Unlocking Doors: Learning from Alternatives to Secure Care in Scotland, The Netherlands, Canada and Hawaii Report by Kate Crowe, 2022 Churchill Fellow. pp. 31–35. Available online: https://www.churchilltrust.com.au/fellow/kate-crowe-vic-2022/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Pilarinos, A.; Kendall, P.; Fast, D.; DeBeck, K. Secure care: More harm than good. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2018, 190, 1219–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enell, S.; Vogel, M.A.; Henriksen, A.E.; Pösö, T.; Honkatukia, P.; Mellin-Olsen, B.; Hydle, I.M. Confinement and Restrictive Measures Against Young People in the Nordic Countries—A Comparative Analysis of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden 2022. Available online: https://www.idunn.no/doi/10.1080/2578983X.2022.2054536 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Pösö, T.; Kitinoja, M.; Kekoni, T. Locking up for the best interests of the child: Some preliminary remarks on ‘special care’. Youth Justice 2010, 10, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessell, S.; Gal, T. Forming partnerships: The human rights of children in need of care and protection. Int. J. Child. Rights 2009, 17, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldson, B. Child imprisonment: A case for abolition. Youth Justice 2005, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldson, B. Child protection and the ‘juvenile secure estate’ in England and Wales: Controversies and concerns. In Youth Justice and Child Protection; Lockyer, A., Stone, F., Hill, M., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2006; pp. 104–119. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, T. Children in Secure Accommodation: A Gendered Exploration of Locked Institutional Care for Children in Trouble; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; Gardner, R. Secure accommodation under the Children Act 1989: Legislative confusion and social ambivalence. J. Soc. Welf. Fam. Law 1996, 18, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muncie, J. Governing young people: Coherence and contradiction in contemporary youth justice. Crit. Soc. Policy 2006, 26, 770–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettmann, J.E.; Jasperson, R.A. Adolescents in residential and inpatient treatment: A review of the outcome literature. Child Youth Care Forum 2009, 38, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eronen, R.; Laakso, R.; Pösö, T. Now you see them—Now you don’t: Institutions in child protection policy. In Social Work and Child Welfare Politics: Through Nordic Lenses 2010; Forsberg, H., Kroger, T., Eds.; Policy Press Scholarship Online: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBeck, K.; Kendall, P.; Fast, D.; Pilarinos, A. The authors respond to comments on the use of secure care in youth. CMAJ 2019, 191, E199–E200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne, R.; Annemarieke, B.; van der Rijken, R.; Scholte, R.; Lange, A. Treatment Outcomes of a Shortened Secure Residential Stay Combined With Multisystemic Therapy: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2019, 63, 2654–2671. [Google Scholar]

- Sköld, J.; Swain, S. Apologies and the Legacy of Abuse of Children in ‘Care’; International Perspectives; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. Available online: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/6895107 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Klag, S.; O’Callaghan, F.; Creed, P. The use of legal coercion in the treatment of substance abusers: An overview and critical analysis of thirty years of research. Subst. Use Misuse 2005, 40, 1777–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevers, S.W.M.; Poelen, E.A.P.; Scholte, R.H.J.; Otten, R.; Koordeman, R. Individualized behavioral change of externalizing and internalizing problems and predicting factors in residential youth care. Psychol. Serv. 2020, 18, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltink, E.M.A.; Ten, H.J.; De Jongh, T.; Van der Helm, G.H.P.; Wissink, I.B.; Stams, G.J.J.M. Stability and change of adolescents’ aggressive behavior in residential youth care. Child Youth Care Forum 2018, 47, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutterswijk, R.V.; Kuiper, C.H.; Harder, A.T.; Bocanegra, B.R.; van der Horst, F.C.; Prinzie, P. Associations between Secure Residential Care and Positive Behavioral Change in Adolescent Boys and Girls. Resid. Treat. Child. Youth 2023, 40, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayfield, H.; Williams, A.; Elliot, M.; Evans, R.; Long, S.; Young, H. The Experience and Outcomes of Young People From Wales Receiving Secure Accommodation Orders. Four Nations Secure Care Symposium. 2023. Available online: https://padlet.com/CYCJ_/four-nations-secure-care-symposium-7vr3313feh6rvm41/wish/2532797565 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Marshall, K. Child Sexual Exploitation in Northern Ireland; Report of the Independent Inquiry. 2014. Available online: https://www.cjini.org/getattachment/f094f421-6ae0-4ebd-9cd7-aec04a2cbafa/Child-Sexual-Exploitation-in-Northern-Ireland.aspx (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Haydon, D. Detained children: Vulnerability, violence and violation of rights. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr. 2020, 9, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority. A Report on the Inspection of the Care Pathways of a Select Group of Young People who Met the Criteria for Secure Accommodation in Northern Ireland; RQIA: Belfast, UK, 2011; Available online: https://www.rqia.org.uk/reviews/review-reports/2009-2012/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Warshawski, T.; Charles, G.; Vo, D.; Moore, E.; Jassemi, S. Secure care can help youth reduce imminent risk of serious harm and prevent unnecessary death. CMAJ 2019, 191, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, F.; Balck, A. Gender Injustice: System-Level Juvenile Justice Reforms for Girls. 2015. Available online: https://njjn.org/uploads/digital-library/Gender_Injustice_Report_Sept-2015.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Creegan, C.; Scott, S.; Smith, R. Use of Secure Accommodation and Alternative Provisions for Sexually Exploited Young People in Scotland. 2005. Available online: https://www.barnardos.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-11/secure_accommodation_and_alternative_provisions_for_sexually_exploited_young_people_in_scotland_2005.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Young, M.P. The struggle of the closed youth care sector with regard to children with very serious problems. Juv. Law Pract. 2016, 1, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jong-de Kruijf, M.P. Decisions on closed placements: The juvenile court needs more freedom of choice. In 100 Years of Juvenile Court; de Graaf, C., Ruitenberg, G., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Deventer, The Netherland, 2022; pp. 89–92. Available online: https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/deprivation-of-liberty-a-review-of-published-judgments (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Roe, A.; Ryan, M. Children Deprived of Their Liberty: An Analysis of the First Two Months of Applications to the National Deprivation of Liberty Court. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. 2023. Available online: https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/children-deprived-of-their-liberty-an-analysis-of-the-first-two-months-of-applications-at-the-national-deprivation-of-liberty-court (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Clark, B.A.; Preto, N.; Everett, B.; Young, J.M.; Virani, A. An ethical perspective on the use of secure care for youth with severe substance use. CMAJ 2019, 191, E195–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northern Territory Council of Social Service. Submission from the Northern Territory Council of Social Service to the Department of Children and Families Secure Care and Protection (Therapeutic Orders) Amendment Bill 2012. Northern Territory, Australia. 2012. Available online: https://www.ntcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Secure-Care-Submission.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Miller, B. Talking Hope. Glasgow: CYCJ. Talking-Hope-Report.pdf. Available online: www.cycj.org.uk (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Harder, A.T.; Knorth, E.J.; Kalverboer, M.E. The inside out? Views of young people, parents, and professionals regarding successful secure residential care. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2017, 34, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldson, B.; Kilkelly, U. International human rights standards and child imprisonment: Potentialities and limitations. Int. J. Child. Rights 2013, 21, 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. ACEs, Distance and Sources of Resilience, Children and Young Peoples Centre for Justice. 2024. Available online: https://www.cycj.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ACEs-Distance-and-Resilience.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Haydon, D. Promoting and Protecting the Rights of Young People Who Experience Secure Care in Northern Ireland. Children’s Law Centre. 2016. Available online: https://damgeohost1.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/CLC/webDocs/Promoting_and_Protecting_the_Rights_of_Young_People_who_Experience_Secure_Care_in_Northern_Ireland_January_2016_final.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Roe, A. What Do We Know about Children and Young People Deprived of Their Liberty in England and Wales? An Evidence Review—Nuffield Family Justice Observatory 2021. Available online: https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/children-and-young-people-deprived-of-their-liberty-england-and-wales (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Williams, A.; Bayfield, H.; Elliot, M.; Smith, L.J.; Evans, R.; Young, H.; Long, S. The Experiences and Outcomes of Children and Young People from Wales Receiving Secure Accommodation Orders; Social Care Wales: Cardiff, UK, 2019; Available online: https://socialcare.wales/cms-assets/documents/The-experiences-and-outcomes-of-children-and-young-people-from-Wales-receiving-Secure-Accommodation-Orders.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Victorian Ombudsman. Own Motion Investigation into Child Protection—Out of Home Care. 2010. Available online: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/4973068 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- State of Victoria. Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Final Report, Summary and Recommendations. 2021. Available online: https://finalreport.rcvmhs.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/RCVMHS_FinalReport_Vol1_Accessible.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Spivakovsky, C.; Steele, L.; Wadiwel, D. Restrictive Practices: A Pathway to Elimination. Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. 2023. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/323642 (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Boyle, J. Evaluation of Intensive Support and Monitoring Services (ISMS) within the Children’s Hearings System. 2018. Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/9517/1/0064165.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Nina Vaswan, N. Intensive Support and Monitoring Service (ISMS) ISMS and beyond a Snapshot of the Service in the Last Two Years and a Longer Term Follow Up. 2009. Available online: https://lx.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/youthjusticeintensivesupportandmonitoringservicereportaug09.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- The Forgotten Child. Stop Gesloten Jeugdzorg|Het Vergeten Kind. Available online: https://www.hetvergetenkind.nl/stop (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Parlan. Available online: https://www.parlan.nl/over-ons (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Youth & Family Wellness Center. 2024. Available online: https://www.kamakakoi.com/kawailoa (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Kawailoa Youth and Family Wellness Center. Available online: https://wearekawailoa.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Gillespie, L.; (Office of Youth Services, Department of Human Services Meeting, Honolulu, HI, USA). Personal communication, 2022.

- Kellogg, W.K. Foundation. 2024. Available online: https://www.wkkf.org/news-and-media/article/2022/10/five-awardees-to-receive-80-million-to-advance-racial-equity-globally/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Patterson, M.; (Juvenile Justice Administrator, Office of Youth Services, Department of Human Services, Honolulu, HI, USA). Personal communication. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crowe, K. Community-Based Alternatives to Secure Care for Seriously At-Risk Children and Young People: Learning from Scotland, The Netherlands, Canada and Hawaii. Youth 2024, 4, 1168-1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030073

Crowe K. Community-Based Alternatives to Secure Care for Seriously At-Risk Children and Young People: Learning from Scotland, The Netherlands, Canada and Hawaii. Youth. 2024; 4(3):1168-1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030073

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrowe, Kate. 2024. "Community-Based Alternatives to Secure Care for Seriously At-Risk Children and Young People: Learning from Scotland, The Netherlands, Canada and Hawaii" Youth 4, no. 3: 1168-1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030073

APA StyleCrowe, K. (2024). Community-Based Alternatives to Secure Care for Seriously At-Risk Children and Young People: Learning from Scotland, The Netherlands, Canada and Hawaii. Youth, 4(3), 1168-1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth4030073