Abstract

Throughout history, Black women have taken their unique lived experiences to make changes through civic behaviors. At the same time, they hold a complex position in society, located at the intersection of multiple marginalizing identities that put them at risk of experiencing distinct forms of discrimination. To date, little research has examined the patterns of Black women’s civic behaviors and associations with discrimination experiences and well-being. This may be particularly salient during emerging adulthood, a key period of sociopolitical development and increasing mental health problems. The current study seeks to address this gap, drawing from theories of intersectionality and sociopolitical development. Participants included 103 emerging adult Black women (Mage = 24.27, SD = 2.76) with a range of civic experiences. Overall, anti-racist action was the most prevalent domain of civic behavior. Participants were about twice as likely to engage in traditional political behaviors (e.g., signing petitions, giving money) than political protest. Latent class analysis was used to identify three unique subgroups of civic behaviors: Stably Committed, Traditionally Engaged, or Low Engagement. Findings also showed that emerging adult Black women classified as Stably Committed experienced more discrimination and higher depressive symptoms. The current findings inform the creation of safe spaces for emerging adult Black women to be civically engaged as they navigate racism and sexism and take action to seek racial justice.

1. Introduction

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”Audre Lorde

The words of Audre Lorde, which embody Kimberlé Crenshaw’s [1] intersectionality scholarship, remind us that we have multiple positionalities that intersect to influence our social experiences and well-being across development. Intersectionality [1] refers to the systems of power, privilege, and oppression that are woven into the legislation, policies, principles, and practices of a society and which combine to give meaning to social categories such as race, gender, sexual orientation, and more [2,3,4]. Intersectionality is a field of study, analytical strategy, and critical praxis meant to be incorporated into all research and practice, as intersectionality is essential to understanding all social phenomena because we live in a diverse society [5]. Even though Crenshaw coined the term, related ideas can be found in the works of Patricia Hill Collins [3], bell hooks [6], Sojourner Truth [7], The Combahee River Collective [2], and others. Intersectionality emerged, in part, as a response to the realization that most theories and mobilization efforts challenging gender and racial inequality solely focused on white women’s and Black men’s perspectives [6,8]. However, Black women hold a unique position in society, as they are living at the intersection of racism and sexism, two deeply rooted systems of oppression within the United States [9,10].

Black women have taken their unique lived experiences to make changes through civic engagement [11], often starting in adolescence and young adulthood [12]. Channeling intersectionality and guided by sociopolitical development theory, we seek to describe young Black women’s civic behaviors and examine links with discrimination experiences and depressive symptoms. This study is vital given the complexity and intersectional nature of Black women’s experiences, which are not fully captured in mainstream research [13]. Further, Black women have often been overlooked and rendered invisible, including in civil rights history [14,15]. Therefore, we begin with a brief review of the history of Black women’s civic engagement.

1.1. The History of Black Women’s Civic Activism

Black communities were historically discouraged or even forbidden from active civic participation due to the potential for challenging society’s dominant class [16]. Exclusionary practices, cultural factors, and structural oppression adversely affected—and continue to affect—the civic participation of Black adolescents and young adults [16,17,18]. For example, the suffrage movement was a fight for voting rights among women and Black men through the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments [19]. However, Black women were often conflicted, feeling they had to prioritize either race or gender [7]. Joining forces with white suffrage activists meant allying with white women who had publicly admitted their racism [7,19] while supporting suffrage solely for Black men, ignoring the rights of Black women, and endorsing a patriarchal structure [7,19].

This uneasiness persists among Black women and girls today, as evidenced by their voices during the 2017 Women’s March [20] and reactions to the overturning of Roe vs. Wade [21,22]. Black women navigating both sexism and racism, commonly referred to as gendered racism, within these respective movements face unique burdens that their white and male counterparts do not encounter [1]. They are often marginalized by male leaders in civil rights movements and sidelined in feminist movements prioritizing issues of white women [3]. This dual struggle forces Black women to advocate for racial and gender equality simultaneously, often without the full support of their peers [2]. Consequently, their contributions and experiences are frequently overlooked, adding an additional layer of strain to their activism and leadership efforts [4].

Black women have used their unique lived experiences to make changes through civic actions at the macro- and micro-levels [11]. Black women have engaged in civic action during slave revolts, the suffrage movement, the club movement, and the civil rights movement [23,24,25], working as suffragists, educators, organizers, lawyers, voters, writers, officeholders, and more [11]. Black women have utilized Black spaces, including clubs, churches, anti-slavery societies, civil rights organizations, and Young Women’s Christian Associations (YWCA), to carve out their agenda, work out their ideas, and do the work of civil rights and racial equality. Organizations such as the Third World Women’s Alliance (New York City, 1968–1977; San Francisco/Oakland, 1971–1978/9), the National Black Feminist Organization (New York City, 1973–1975), the Combahee River Collective (Boston, 1975–1980), the National Alliance of Black Feminists (Chicago, 1976–1980), and Black Women Organized for Action (San Francisco/Oakland, 1973–1980) have been the spaces Black women have used to push the needle forward [11] for more inclusive agendas. Activists in the civil rights movement and historians consider leaders such as Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Septima Clark as the “Mothers of the Movement” [11]. They are recognized for their powerful, steady presence and grassroots analysis of racism despite history trying to erase these women’s stories and contributions.

1.2. Emerging Adult Civic Engagement and Well-Being

Emerging adulthood, the unique developmental period between 18–29 years old, is widely recognized as a critical period for civic development and participation [26,27]. Across this transitory developmental period, emerging adults formulate and test their civic values, examine aspects of their identity, and become increasingly aware of social issues. Overall, civic engagement (including civic attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors) increases during emerging adulthood. Using data from Monitoring the Future, an ongoing national multi-cohort, multi-wave longitudinal study, Wray-Lake et al. [28] found that electoral engagement and political voice rise from ages 18 to 30. However, there is also important heterogeneity in civic engagement across emerging adulthood, demonstrated by Finlay et al. [29] using a large sample of 19–29 year-old emerging adults from the AmeriCorps National Study. Results pointed to three unique civic engagement trajectories: inactive (little to no civic activity across emerging adulthood), voting-involved (often or always vote in all elections, volunteer, and do other civic actions), and highly committed (participate in many types of civic actions, with an emphasis on attending community events and meetings) [29].

There is increasing attention to how early civic engagement benefits young people and society [30]. The positive effects of civic engagement among young people can be felt both at the individual level (e.g., better emotional regulation, a greater sense of empowerment and social responsibility) and at the community level (e.g., a greater likelihood of participation in civic and political activities as an adult, increased tolerance toward people from disadvantaged communities) [31,32]. Further, these associations may have long-term developmental significance. For example, using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, Ballard and colleagues [33] found that civic engagement during adolescence and emerging adulthood was positively associated with socioeconomic position later in adulthood, and some forms of engagement (i.e., voting, volunteering) were associated with improved mental health and health behaviors in adulthood, too.

Civic engagement can also be a protective factor for young people facing sociopolitical stress and/or promote positive identity development [34,35]. In particular, there is evidence that engagement in anti-racist civic participation could be a coping mechanism for marginalized youth who experience inequality, such as racial/ethnic discrimination [36]. Chan et al. [37] found that emerging adults of color who actively participated in civic activities were more hopeful about the future, more satisfied with their lives, attained higher levels of education, were less likely to engage in criminal acts, and were more likely to participate in future civic activities.

However, little is known about patterns of civic engagement among emerging adult Black women, specifically [38]. The unique experiences and challenges of Black women and girls, shaped by their intersectional, multiply marginalized lived experiences, are often the catalyst for their sociopolitical development (SPD), a process of growth in knowledge, analytical skills, emotional faculties, and capacity for civic engagement [39]. In particular, the SPD framework argues that experiences of marginalization (e.g., structural and individual discrimination) can contribute to critical social analysis, leading to action that promotes social change [39]. For example, emerging adults from traditionally marginalized backgrounds, including women, are more likely to engage in system-challenging civic engagement (e.g., activism in support of the Black community) than those from more privileged backgrounds [40].

Despite the potential positive outcomes of early civic engagement, certain civic behaviors among Black individuals may carry risks or costs, including police violence against people of color [41,42]. Physical and mental health may be compromised by the fear experienced by Black individuals when engaging in protest and being potentially exposed to violence [43,44]. Finally, civic engagement is likely directly related to discrimination in a few key ways. Discrimination could catalyze civic engagement among Black emerging adults, with engagement sometimes described as an adaptive coping strategy for those facing oppression [45,46,47]. On the other hand, civic engagement has been associated with higher self-reported discrimination by youth of color [45], and discrimination may lead people from marginalized groups to withdraw from civic participation entirely [48,49]. Overall, the link between civic engagement and discrimination experiences may vary based on the domain and type of civic action and/or measurement of discrimination. However, discrimination experiences among Black women must be examined beyond civic engagement, as it has a bearing on their well-being.

1.3. Discrimination and Well-Being

Discrimination, a form of structural racism, is a serious problem that functions as a cultural norm woven through the fabric of American society. It is defined as rules, norms, routines, patterns of attitudes, and behavior in individuals, institutions, and other societal structures that represent obstacles to groups or individuals in achieving the same rights and opportunities that are available to the majority of the population [50]. Discrimination continues to contribute to the historical and contemporary marginalization of Black communities through traditional political and social systems in the U.S. [51]. Numerous discriminatory practices have had significant immediate and long-term repercussions on Black people’s psychological health [52,53].

Specifically for emerging adult Black women, discrimination is a complex experience given their multiple marginalized identities. In alignment with Crenshaw’s [4] intersectionality framework, intersectional discrimination is a dynamic experience based on the inseparable embodiment of Blackness and girl/womanhood, creating distinct and specific forms of discrimination, such as gendered racism and misogynoir [54]. Misogynoir was created to highlight “the specific hatred, dislike, distrust, and prejudice directed toward Black women” [55]. Misogynoir illuminates one example of intersectional marginality—how people and society perceive and treat Black women defines the bounds of them being (un)worthy of respect and care. This marginality specific to Black women is broadly reflected in culture and society (e.g., cultural racism) and can be useful in understanding experiences of and reactions to (e.g., coping) intersectional discrimination. Understanding this reality has real implications for health outcomes and coping mechanisms among Black women [56,57]. These assertions are much more complex than the simplistic representation of uni-dimensional discrimination [1,4,58].

Although research on intersectional discrimination and health is still evolving, there is growing evidence that discrimination based on race/ethnicity or sex can lead to adverse outcomes such as declining physical and mental health, psychiatric symptoms, and health inequalities [59,60,61,62,63]. For example, a meta-analysis of 29 studies found that self-reported racial discrimination was related to poor mental health, preclinical indicators of disease, and negative health behaviors [62]. Beyond individual experiences, even second-hand or vicarious experiences of discrimination [64] may lead to poor health through psychological and behavioral responses, biological and neural processes, and healthcare underutilization [65,66,67]. These adverse effects must be examined from a structural lens rather than examined at an individual level.

1.4. Theoretical Framing

SPD theory is rooted in the perspectives of liberation psychology and developmental psychology as it aims to advance social equality [68]. While this framework has been primarily used to explain positive youth development (PYD) regarding civic engagement (e.g., critical action) among younger adolescents, it can also be applied to emerging adults. For example, a multidimensional framework of Black college women’s SPD and activism [38] calls for researchers and scholars to more deeply examine communities’ experiences of intersecting oppressions and their agentic and resistant responses to such oppression. Leath et al. discussed eight themes—gaining knowledge, self-advocacy, sisterhood, self-love, educating others, collective organizing and leadership, community care, and career aspirations—as the basis of the framework regarding Black women’s SPD and activism [38]. Hence, the traditional SPD framework can be modified to illuminate the circumstances in which emerging adult Black women become civically engaged.

SPD draws on intersectionality as a framework to examine how one’s political development is influenced by one’s intersecting identities, communities, and experiences of oppression and marginalization [69]. Most closely tied to political intersectionality, SPD points to the “ways that those who occupy multiple subordinate identities, particularly women of color, may find themselves caught between the sometimes conflicting agendas of two political constituencies to which they belong” [4] and illuminates the sociopolitical development process of emerging adult Black women that is grounded in their lived experiences and understandings of interlocking systems of oppression. While SPD is highlighted across civic engagement literature, the field has yet to incorporate intersectionality with SPD, which is imperative to understand the nuances of civic development among young Black women from a structural lens.

1.5. Current Study

Despite a history of Black women being civically aware and active [11], few studies have looked at the unique patterns of civic behaviors among emerging adult Black women [70]. Modern examples of Black women’s activism and power include those leading the BLM movement, such as Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi. These women intentionally resisted the homophobic and sexist leadership models of past movements, fostering a space that valued the contributions of queer individuals and women, ensuring that their voices were fully included within the movement. Further, little developmental research has examined youth civic engagement outside institutional socializing agents (e.g., schools and universities). Overall, we lack a critical understanding of emerging adult Black women’s sociopolitical development, specifically how different patterns of civic behaviors relate to their well-being. Informed by theories of intersectionality and SPD, the current study explores civic behavior patterns, discrimination experiences, and depressive symptoms among emerging young adult Black women (aged 19–29) using descriptive, latent class, and regression analyses.

Three aims guide this study: (1) Examine how emerging adult Black women are engaged in different civic behaviors across sociopolitical causes, identifying unique subgroups of civic participation; (2) Describe the discrimination experiences of emerging adult Black women; and (3) Examine associations between civic behavior classes and (a) perceived discrimination and (b) depressive symptoms. Based on the literature, we hypothesized there would be high, low, and mixed civic behavior classes. We also hypothesized that Black women will mostly attribute their discrimination experiences to both race and gender. Finally, we hypothesize that emerging adult Black women categorized as highly engaged will report higher discrimination and better mental health.

It is important to note that this study took place during 2016–2017, a period marked by the active and salient presence of the BLM movement in the USA and the election of Donald Trump as the 45th President. This sociopolitical context is crucial as it highlights the connection between the contemporary sociopolitical landscape and Crenshaw’s scholarly work on intersectionality. Specifically, we acknowledge two key influences: (1) the rise of the BLM movement, which confronted systemic racism and violence while emphasizing the interconnected challenges of race, gender, and sexuality, and (2) the 2016 election of Donald Trump, which was marked by racially charged and sexist rhetoric that exacerbated stress and deepened inequalities experienced by marginalized groups during this period [71]. This sociopolitical context underscores the importance of intersectional analysis in addressing the multifaceted nature of discrimination and resistance within social justice movements.

2. Methods

2.1. Researcher Reflexivity and Positionality

The authors of this project are three Black women and one white woman with variations in their own civic engagement. In writing this piece, we reflected on our own connections and disconnections to civic engagement and discrimination. We acknowledge our positions of power, privilege, and marginalization.

2.2. Sample Demographics

This study uses secondary data collected from the Health + Activism study [72], created to semi-replicate the Women’s Life Paths Study (WLPS) [73] with a more diverse sample (i.e., more racial and gender diversity). The WLPS longitudinally tracked career development and life changes among a group of women from the University of Michigan who graduated between 1967 and 1973. Data collection for the Health + Activism survey continued over six months, beginning in October 2016 and ending in March 2017. The sample total was 722 individuals. The age of respondents ranged from 19 to 38 years old, and the sample was 54.3% women and 43.4% men. Using a stratified sampling method to oversample for traditionally underrepresented groups, the racial-ethnic diversity of the sample yielded 37.1% Black/African American, 28.3% white, 15.2% Asian, 15.2% Latinx/Hispanic, 3.3% American Indian/Native American/Indigenous, and 0.7% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander respondents. The current study uses a subsample of emerging Black women (n = 103), with the average age being 24.27 years old (19–29 yr old; SD = 2.76). The majority of the Black women identified as heterosexual (83.5%), moderate in political orientation (35.0%), and had some college experience (54.4%) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Demographics.

2.3. Procedures

This study was approved by Wesleyan University’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited exclusively through Amazon MTurk. Compared to the general population, MTurk workers closely resemble undergraduate subject pools and other internet samples and are likely to be more ethnically and socioeconomically diverse [72]. The survey was administered through Qualtrics, an online platform, and included sociodemographic information and measures related to general social and political attitudes. An initial screening question was, “Have you ever attended any of the following activities? Check all that apply”. Answer options were (1) Concert, (2) Happy hour, (3) Service trip, (4) Church, (5) Fundraiser, (6) Rally, (7) Bonfire, (8) Retreat, (9) Lecture, (10) Sporting event, (11) Pep rally, and (12) Volunteer event. In addition to a screener question, the research team screened and hand-checked duplicate email and IP/ID addresses. Due to the forced-answer format applied to survey items, there were no missing data on major variables.

2.4. Measures

Civic Behaviors. Modified from Duncan’s [73] women’s rights activism measure, respondents were asked about their participation in twenty civic causes of various domains (e.g., women’s rights, racial equality, The Democratic Party/Candidate). The instructions read, “Please indicate how you have been involved in any of the following causes during the past two years by checking all boxes that are applicable”. Involvement pertained to six actions: signed a petition, attended a rally or demonstration, attended a meeting, wrote a letter or called a public office, being an active member of an organization, and/or giving money. Responses ranged from 0 to 6 actions taken.

We divided civic behaviors into two categories based on Hope, Pender, and Riddick’s [74] conceptualization of high-risk and low-risk activism in the Black community. Five actions (signed a petition, attended a meeting, wrote a letter or called a public office, was an active member of an organization, and gave money) were combined into one category labeled “Traditional Political” as these actions demonstrate traditional forms of civic behaviors deemed as relatively safe and pose minimal risks. Attending a rally or demonstration was labeled as “Political Protest” as it is a riskier civic behavior that could potentially result in physical harm or arrest. After creating the binary action categories for each civic cause, we organized the civic causes into six civic behavior domains: Anti-Racism, Reproductive Rights & Healthcare, Liberal Values, Humanitarian, Immigration and International Human Rights, and Conservative Values. These domains were conceptually created based on underlying themes of civic causes. For example, anti-racism consists of the Black Lives Matter Movement, civil rights, and racial equality (see Supplementary Table S1).

Discrimination. Discrimination was assessed using the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS), a ten-item measure of general mistreatment without reference to a specific social category [75]. The frequency of each type of mistreatment was assessed on a 4-point scale (1 = never; 4 = often. Sample items: “People act as if they think you are not smart”, “You are treated with less respect than other people”). Participants were asked to rate their experiences of everyday discrimination over the past year. The measure was calculated by taking the average of the ten items. The sample mean was 2.09 (SD = 0.56). An additional prompt asked participants to describe the reason(s) for their experiences if they answered “sometimes” or “often” to at least one of the ten items. Response categories included race/ethnicity, gender, age, income level, language, physical appearance, sexual orientation, and others. The EDS has been found to be reliable in Black samples. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84 in our sample of young Black women.

Depressive Symptoms. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Mental Health Inventory (MHI), an eleven-item questionnaire measuring characteristic attitudes and symptoms of depression [76]. The frequency of each item was assessed on a six-point scale (1 = none of the time; 6 = all the time. Sample item: “Have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up?”). The measure was calculated by taking the average of the 11 items. The sample mean for depressive symptoms was 2.94 (SD = 1.02; α = 0.90).

2.5. Analytic Plan

The data was analyzed using RStudio Version 2023. First, descriptive analysis was employed to examine patterns of civic engagement and discrimination among Black Women. Then, latent class analysis (LCA) was employed to identify different subgroups of civic engagement based on individual differences in civic actions (i.e., Traditional Political or Political Protest) and domains (i.e., Anti-Racism, Reproductive Rights & Healthcare, Liberal Values, Humanitarian, Immigration and International Human Rights, and Conservative Values) within the sample [77]. This statistical method provides a person-centered approach to multidimensional constructs like civic engagement, enabling us to identify the dynamics of emergent subpopulations and patterns across the intersection of the civic engagement domain and specific actions Black women engage in [78]. We used the poLCA package in R, designed to handle polytomous outcome variables [79]. We fitted seven models to the data. Model fit was determined by comparing standard fit indices, including the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Entropy was used as an index of classification accuracy. We also evaluated each solution’s interpretability to determine which model fit best. The model with a low BIC was chosen as the best fitting model, as some researchers state that lower BICs indicate better fit and BIC is the most reliable indicator of model fit [80,81]. In addition, entropy values above 0.80 are deemed acceptable as it is indicative of a clear delineation of classes [82]. Linear regression was employed to examine the relationship between civic engagement class and discrimination and mental health. Discrimination and depressive symptoms were regressed on civic engagement classes, with separate models for each dependent variable.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Civic Behaviors

Half of all Black women in the sample reported at least one form of involvement in anti-racist civic behaviors (50.0%) in the past two years (i.e., BLM, civil rights, racial equality), which was the most prevalent civic domain. Black women in this sample were also highly involved in domain causes that aligned with liberal values, reproductive rights & healthcare, and humanitarianism, with 40–47% of the sample involved in at least one activity in each of these domains in the past two years. Fewer participants were civically engaged in international human rights or conservative causes (see Table 2). Overall, participants were about twice as likely to be engaged in traditional political actions (e.g., petitioning, giving money, calling public office) than political protest. For example, 24.3% of women participated in some sort of political protest for anti-racism versus 49.9% who engaged in other civic activities such as writing a letter or donating money. The one exception is humanitarian issues: very few participants engaged in protest activities for civic issues like homelessness, anti-war, and environmental rights and concerns.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Black Women’s Civic Engagement (N = 159).

Within the 24.3% of Black women who participated in a political protest for anti-racism, 21 (41.2%) also participated in traditional civic actions for anti-racism. Out of the 40.8% of Black women who participated in traditional political activities for reproductive rights & healthcare, 10 (23.8%) Black women also participated in some sort of political protest for this domain. For traditional political liberal actions, 27.3% (n = 12) also participate in a protest for liberal civic issues. Within the humanitarian domain, international human rights, and conservative civic domains, less than 10% of women engaged in traditional and protest actions. Overall, 33.0 percent of women engaged in both traditional and political protest actions compared to 35.0 percent only engaged in traditional actions, and 3.9 percent only engaged in a protest.

3.2. Classes of Civic Engagement

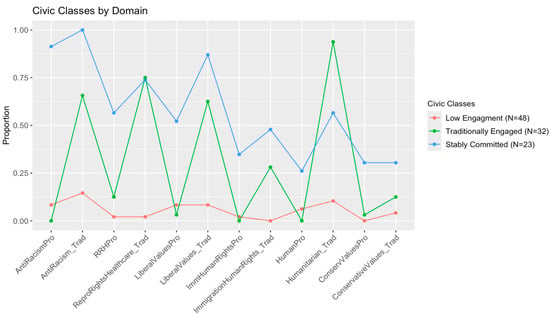

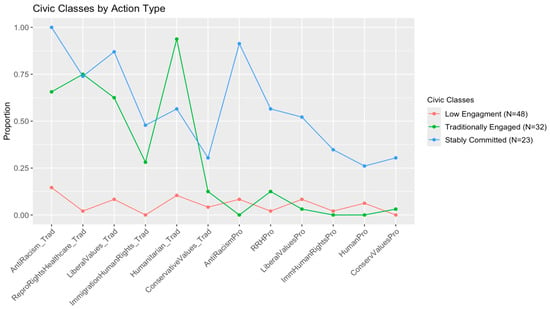

Using standard fit indices, a three-class solution was selected. The three-class solution had a low BIC and aBIC deemed acceptable and acceptable entropy (see Table 3). The largest class was labeled Low Engagement (n = 48), given that participants in this class reported the lowest civic engagement across both traditional political actions and political protests. The second-largest class was labeled Traditionally Engaged (n = 32). Participants in this class had mixed civic engagement as they were highly engaged in traditional political actions around anti-racism, liberal values, and reproductive rights & healthcare, but low protest actions across all civic domains. The smallest class was labeled Stably Committed (n = 23). Participants in this class were stably committed to both traditional and protest actions across all civic cause domains. The highest participation for this class was traditional political anti-racist action, meaning that all women engaged in at least one form of traditional civic engagement for anti-racism causes (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Table 3.

Fit indices for computing the best-fit model for Civic Engagement Classes.

Figure 1.

Civic behavior classes among Black women categorized by civic domains.

Figure 2.

Civic behavior classes among Black women are categorized by type of civic action.

3.3. Descriptive Analysis of Discrimination

Overall, race was the primary attribute of discrimination experiences. Among the sample, 52.4 percent of Black women reported race as the reason for people acting as if they were better than them. Regarding gender, 29.1% of Black women reported this attribute as the reason for people acting as if they think they are not smart. Also, twenty-nine women (28.2%) marked age as the reason for people acting as if they think they are not smart. About 22% of women reported appearance as the reason people treated them with less courtesy (see Supplementary Table S2).

3.4. Civic Behavior Classes Relationship to Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms

Regression analysis revealed a significant difference between the Low Engagement and Traditionally Engaged classes and between the Low Engagement and Stably Committed classes. The Traditionally Engaged class exhibited significantly higher discrimination scores than the Low Engagement class (b = 0.31, p = 0.009). The Stably Committed class exhibited significantly higher discrimination scores than the Low Engagement class (b = 0.35, p = 0.042). Everyday discrimination was positively associated with depressive symptoms among Black women in this sample: For each one-unit increase in EDS, there was a 0.592-unit increase in depressive symptoms (p = 0.001). There was also some evidence suggesting that more civically engaged women (i.e., those in the Stably Committed class) had more depressive symptoms compared to the other two classes. Women in the Stably Committed class had more depressive symptom scores compared to both women in the Low Engagement class (b = 0.741, p = 0.017) and the Traditionally Engaged class (b = 0.678, p = 0.031), controlling for everyday discrimination (See Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Regressions Analysis for Civic Engagement Classes and EDS.

Table 5.

Regressions Analysis for Civic Engagement Classes and Depressive Symptoms.

4. Discussion

One of the tenets of transformative intersectionality links lived experiences (e.g., misogynoir) to systems of structural oppression (gendered racism), considering applications to social justice, activism, and systems change, which is representative of the current study [83]. Our study found that anti-racist action dominated civic behavior, and Black women’s involvement in traditional political behavior was about twice as common as political protest. We also found three unique subgroups of civic behaviors among Black women (i.e., Stably Committed, Traditionally Engaged, and Low Engagement), as well as emerging adult Black women who were classified as Stably Committed reporting higher depressive symptoms and more discrimination. Applying an intersectional lens to sociopolitical development theory, this study points to the complex relationship between civic behaviors, discrimination, and well-being among emerging adult Black women.

4.1. Black Women’s Civic Engagement

Given the lack of studies examining Black women’s civic engagement, Aim 1 was descriptive. It was hypothesized that Black women would be more engaged in the race-based civic domain, given the salience of race and racism in the United States, and engage in higher levels of political protest. In addition, it was also hypothesized that high, low, and mixed civic engagement classes would emerge. Overall, for aim 1, support for our hypotheses was mixed as Black women had the highest engagement for the Anti-Racism civic domain but were twice as likely to be engaged in traditional political activities (e.g., sign a petition, give money, call public office) than political protest. One potential reason for differences across the two types of civic engagement action is that one’s marginalized identity may influence whether one engages in low-risk (i.e., traditional political) vs. high-risk (i.e., political protest) activism [74]. As Black women recognize and experience the pervasiveness of misogynoir within society, they may be inclined to less risky activism that is manageable and accessible to combat this massive social structure. However, these findings center on Black women’s civic engagement and suggest that Black women are engaged despite media portrayals and even academic scholarship that may lead one to believe that Black men are at the forefront of these movements, which is historically incomplete. We also acknowledge that depending on certain contextual factors, such as geographic location or political climate, actions that are deemed low-risk (e.g., signing a petition) can be high-risk actions. For example, while the act of signing a petition is deemed low-risk, in certain contexts—during the Supreme Court case of protecting or overturning Roe v. Wade, for example—it can be high risk as it can have social, physical, and/or financial implications [84].

As for our LCA findings, our results supported previous research [29] in which emerging adults were categorized into three groups, which were labeled: Stably Committed (i.e., Black women who participate in many types of civic actions and support many civic causes), Traditionally Engaged (i.e., engaged in traditional political, civic actions such as voting and donating money), and Low Engagement (i.e., little to no engagement across all civic domains). While these classes show the variation of civic engagement, they also illuminate the need to be inclusive of ways of being and actions that extend the definition of civic engagement. Particularly for Black women, resistance may be a more appropriate construct to uniquely capture the breadth of Black women’s actions toward liberation and against oppression. Despite low civic engagement being the biggest class, these findings highlight that Black women continue to push for a more just and equitable society in different magnitudes.

4.2. Civic Engagement, Discrimination, and Depressive Symptoms

With regard to discrimination, our hypothesis that race and gender would be primary attributions for discrimination was not supported as race was the primary attribute for discrimination experiences across all contexts. Using recent data from the Health + Activism study [73], these findings provide a snapshot of Black women’s experiences with discrimination in the United States. Despite public perceptions of racism not being an issue anymore [85], Black women continue facing significant barriers to equal treatment across multiple contexts, negatively affecting their health and safety. The primacy of race and racism in America is ingrained into the very fabric of this country, making it the most salient attribute of discrimination [86]. However, taking into account the specific lived experience of Black women, the finding of race being the primary attribute of discrimination is still rooted in misogynoir and viewed through an intersectional lens. As we know, racism and sexism are mutually interlocked; therefore, Black women’s gender is racialized, and their race is gendered.

The discrimination experienced by Black Americans does not simply contradict American values of fairness and equality of opportunity. It also has very real health consequences, such as mortality, hypertension, depression, anxiety, and psychological distress [63,87,88,89]. For Black women, those subjected to higher levels of discrimination report decreased well-being and are deemed more likely to report mental health issues and overall health concerns [90]. Our findings show that Black women in the Stably Committed class experienced more everyday discrimination, and when controlling for discrimination experiences, the Stably Committed women had more depressive symptoms than the other two groups. This highlights the potential health risks of civic engagement, which suggests that civic engagement could be detrimental to mental health. We must acknowledge the heavy load they carry in the face of misogynoir, and at times, their mental health is the cost they pay. So, where do we go from here, as we know that civic engagement alone is not enough to mitigate the negative effects of discrimination and declining mental well-being? We need system-level changes to reduce these adverse effects.

4.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study centers young Black women’s civic engagement, using an intersectional lens and a person-centered approach to understand their unique patterns of civic engagement, across both domains and actions. Given the minimal representation of Black women’s experiences and actions in civic scholarship and how they are often excluded from larger conversations on activism and civic engagement within the United States, this study addressed a vital dearth in research. While the small sample size and cross-sectional data limit the interpretation of temporal precedence and generalizability of our findings, this work aims to provide foundational scholarship with an overlooked and marginalized population as well as contribute to the developmental literature of civic engagement and the utility of understanding how folks engage with different forms and domains of engagement. Additionally, given challenges with MTurk, such as vulnerability to web bots, self-misrepresentation, social desirability bias, and MTurker non-naïvete [91], these research questions should be explored in community samples.

Additional limitations include the limited focus on traditional and political protest actions. Digital or online activism (e.g., social media, blogs) has become an increasingly popular tool for young people to get involved in politics and social movements [92,93]; however, online activism was not measured in the current study. Future research should examine online activism as a space that young Black women use to resist systems of oppression in their everyday lives and find community and support. Future research should also examine how routine resistance (i.e., a novel concept defined here as the micro-level civic actions that Black women may employ to combat daily experiences of oppression) impacts Black women’s sociopolitical development and well-being. This study did not examine causal factors, particularly regarding the extent to which heightened experiences of discrimination and depression among Black women activists may drive their activism. While the current research highlights the relationship between these experiences and activist engagement, it does not delve into the underlying mechanisms that may explain this relationship. Future research should aim to explore the causal pathways that link discrimination and depression to activism among Black women. While we acknowledge our use of an intersectional lens in this cross-sectional, quantitative study, future research should utilize mixed methods to ascertain the deeper nuances of the lived experiences of Black women regarding intersectional discrimination, mental health, and civic engagement that cannot be fully captured through a quantitative approach.

Despite these limitations, this study provides insight into potential ways to promote Black girls’ and women’s health and well-being. First, given that civic engagement could be a protective factor or risk factor for Black women’s mental health, as suggested by this study and others [40,94], it may be helpful for parents, school administrators, and community organizers to consider various ways to participate in and create opportunities for young Black girls to engage in civic and political activities while being aware of the risk and mental input associated with being civically engaged. For example, civic engagement could promote well-being as a way to exhibit agency in the face of oppression [95]. Youth programs, such as Generation Citizen [96] and Brotherhood Sister Sol [97], aim to create opportunities for youth to be civically involved, which is linked to benefits for the youth and their community [98]. Second, these findings suggest the need to create safe spaces that offer Black women and girls a place to unload, create community, and have critical dialogue tailored to their unique societal location. Affinity groups and spaces where Black women and girls can escape for affirmation, understanding, and solidarity are crucial for their mental health, academic functioning, and positive identity development [99,100].

5. Conclusions

The present study advances the literature on young Black women’s unique civic engagement profiles. Emerging adult Black women who were stably committed to both traditional and protest actions across a variety of civic domains experienced more discrimination and worse mental well-being than their peers. The current findings and future directions can come together to inform the creation of safe spaces for Black women to be civically engaged in as they navigate racism and sexism and take action to seek racial justice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/youth4030068/s1, Table S1: Civic Domains; Table S2: Frequency Percentages of Black Women’s Perceived Discrimination Attributes.

Author Contributions

J.B.J., H.S.V. and L.T.H. conceptualized the study design and methodology; H.S.V. supervised the data collection for the Health + Activism Study; J.B.J. wrote the original draft of this paper; L.T.H. drafted sections of the paper and critically reviewed and edited the paper; H.S.V. and N.L.B. critically reviewed and edited the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wesleyan University (Project Number: 20160229-sversey-HAS–PC 04.04.17) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Crenshaw, K.W. Toward a Race-Conscious Pedagogy in Legal Education. Nat. Black Law J. 1989, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- The Combahee River Collective. The Combahee River Collective Statement. 1978. Available online: https://americanstudies.yale.edu/sites/default/files/filesKeyword%20Coalition_Readings.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, 12th ed.; South End Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Truth, S. Ain’t I a Woman? Women’s Rights Convention, Old Stone Church: Akron, OH, USA, 1851. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, G.T.; Hull, A.G.; Bell-Scott, P.; Smith, B. All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies; Feminist Press at CUNY: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, F.M. Double jeopardy: To be Black and female. In The Black Woman: An Anthology; Cade, T., Ed.; Signet: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.A.; Williams Awodeha, N.F.; Jones, D.S.; Flowers-Roe, L. Experiences of Sexism and Racism among Black Women Who Hold a Doctorate. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2022, 00221678221113099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.S. Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All; First Trade Paperback Edition; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, E.D.; Harris, J.; Smith, C.D.; Ross, L. Facing the rising sun: Political imagination in Black adolescents’ sociopolitical development. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 867749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (Revised Tenth Anniversary Edition), 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, S.M.; Pasek, J. Intersectional Invisibility Revisited: How Group Prototypes Lead to the Erasure and Exclusion of Black Women. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2020, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Shorter-Gooden, K. Shifting: The Double Lives of Black Women in America; Perennial, HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Jankowski, M. Minority Youth and Civic Engagement: The Impact of Group Relations. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2002, 6, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, L.D. Prejudice as Group Position: Microfoundations of a Sociological Approach to Racism and Race Relations. J. Soc. Issues 1999, 55, 445–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, B.C. “There’s Still Not Justice”: Youth Civic Identity Development amid Distinct School and Community Contexts. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2007, 109, 449–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, T.L. Commemorating the Forgotten Intersection of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments. St. John’s Law Rev. 2022, 94, 899–926. [Google Scholar]

- Haumesser, L. The Women’s March Is Riddled with Divisions. But That Doesn’t Mean Feminism Is in Crisis. The Washington Post. 2019. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/01/18/womens-march-is-riddled-with-divisions-that-doesnt-mean-feminism-is-crisis/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Council, J.; Philogene, H. The Three Biggest Implications for Black Women from Roe v. Wade’s Fall. Forbes. 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jaredcouncil/2022/06/28/how-the-overturning-of-roe-v-wade-disproportionately-affects-black-women/?sh=6b165f7f14c1 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Gonzales, M. Race and Roe: Black Women Talk Effects of Court Decision. Society for Human Rights Management; SHRM. 2022. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/behavioral-competencies/global-and-cultural-effectiveness/pages/race-and-roe-black-women-talk-effects-of-court-decision.aspx (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Giddings, P. When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America, 1st ed.; W. Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Guy-Sheftall, B. Daughters of Sorrow: Attitudes toward Black Women, 1880–1920; Black Women in United States History; Carlson Pub: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Terborg-Penn, R. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920; Blacks in the Diaspora; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, A.; Wray-Lake, L.; Flanagan, C. Civic engagement during the transition to adulthood: Developmental opportunities and social policies at a critical juncture. In Handbook of Research on Civic Engagement in Youth; Sherrod, L.R., Torney-Purta, J., Flanagan, C.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, M.; Wilkenfeld, B. The stability of political attitudes and behaviors across adolescence and early adulthood: A comparison of survey data on adolescents and young adults in eight countries. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray-Lake, L.; Arruda, E.H.; Schulenberg, J.E. Civic Development across the Transition to Adulthood in a National U.S. Sample: Variations by Race/Ethnicity, Parent Education, and Gender. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 1948–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, A.K.; Flanagan, C.; Wray-Lake, L. Civic Engagement Patterns and Transitions over 8 Years: The AmeriCorps National Study. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 1728–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, E.C. Rethinking Civic Engagement: How Young Adults Participate in Politics and the Community. 2022. Available online: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/rethinking-civic-engagement (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- McGuire, J.; Gamble, W. Community service for youth: The value of psychological engagement over number of hours spent. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, M.; Youniss, J. A developmental perspective on community service in adolescence. Soc. Dev. 1996, 5, 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, P.J.; Hoyt, L.T.; Pachucki, M.C. Impacts of Adolescent and Young Adult Civic Engagement on Health and Socioeconomic Status in Adulthood. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 1138–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, E.C.; Spencer, M.B. Civic engagement as an adaptive coping response to conditions of inequality: An application of Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST). In Handbook on Positive Development of Minority Children and Youth; Cabrera, N.J., Leyendecker, B., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Rollero, C.; Rizzo, M.; Di Carlo, S.; De Piccoli, N.; Fedi, A. Educating Youth to Civic Engagement for Social Justice: Evaluation of a Secondary School Project. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshner, B.; Ginwright, S. Youth Organizing as a Developmental Context for African American and Latino Adolescents. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.Y.; Ou, S.-R.; Reynolds, A.J. Adolescent Civic Engagement and Adult Outcomes: An Examination among Urban Racial Minorities. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1829–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leath, S.; Ball, P.; Mims, L.; Butler-Barnes, S.; Quiles, T. “They Need to Hear Our Voices”: A Multidimensional Framework of Black College Women’s Sociopolitical Development and Activism. J. Black Psychol. 2022, 48, 392–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, R.J.; Williams, N.C.; Jagers, R.J. Sociopolitical development. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornbluh, M.; Davis, A.; Hoyt, L.T.; Simpson, S.B.; Cohen, A.K.; Ballard, P.J. Exploring civic behaviors amongst college students in a year of national unrest. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 2950–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajana, M. Black Lives Matter Activist Oluwatoyin Salau Found Dead | Time. Time. 2020. Available online: https://time.com/5853752/oluwatoyin-salau-black-lives-matter-death/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Pavilonis, V. Fact Check: Thousands of Black Lives Matter Protesters Were Arrested in 2020. USA Today. 2020. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2022/02/22/fact-check-thousands-black-lives-matter-protesters-arrested-2020/6816074001/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Anyiwo, N.; Palmer, G.J.; Garrett, J.M.; Starck, J.G.; Hope, E.C. Racial and Political Resistance: An Examination of the Sociopolitical Action of Racially Marginalized Youth. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 35, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, J.M.; Danforth, L.; Frisby, C.M.; Warner, B.R.; Ferguson, M.W.; Houston, J.B. Posttraumatic Stress Related to the Killing of Michael Brown and Resulting Civil Unrest in Ferguson, Missouri: Roles of Protest Engagement, Media Use, Race, and Resilience. J. Soc. Soc. Work. Res. 2020, 11, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophe, N.K.; Martin Romero, M.Y.; Hope, E.; Stein, G.L. Critical Civic Engagement in Black College Students: Interplay between Discrimination, Centrality, and Preparation for Bias. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2021, 92, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, E.C.; Gugwor, R.; Riddick, K.N.; Pender, K.N. Engaged Against the Machine: Institutional and Cultural Racial Discrimination and Racial Identity as Predictors of Activism Orientation among Black Youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 63, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Johnson, R.L. Prosocial Involvement among African American Young Adults: Considering Racial Discrimination and Racial Identity. J. Black Psychol. 2012, 38, 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskooii, K.A.R. Perceived Discrimination and Political Behavior. Br. J. Political Sci. 2020, 50, 867–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja, A.D.; Ramirez, R.; Segura, G.M. Citizens by Choice, Voters by Necessity: Patterns in Political Mobilization by Naturalized Latinos. Political Res. Q. 2001, 54, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.A.; Arkin, E.; Proctor, D.; Kauh, T.; Holm, N. Systemic and Structural Racism: Definitions, Examples, Health Damages, and Approaches to Dismantling: Study examines definitions, examples, health damages, and dismantling systemic and structural racism. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, E.C.; Skoog, A.B.; Jagers, R.J. “It’ll Never Be the White Kids, It’ll Always Be Us”: Black High School Students’ Evolving Critical Analysis of Racial Discrimination and Inequity in Schools. J. Adolesc. Res. 2015, 30, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, A.D.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Boyle, A.E.; Polk, R.; Cheng, Y.P. Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 855–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaton, E.K.; Caldwell, C.H.; Sellers, R.M.; Jackson, J.S. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1288–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens-Watkins, D.; Perry, B.; Pullen, E.; Jewell, J.; Oser, C.B. Examining the Associations of Racism, Sexism, and Stressful Life Events on Psychological Distress among African-American Women. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2014, 20, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M. Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.S.; Womack, V.; Jeremie-Brink, G.; Dickens, D.D. Gendered racism and mental health among young adults U.S. black women; The moderating roles of gendered racial identity centrality and identity shifting. Sex Roles 2021, 85, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, Y.L. Gendered Racism: A Phenomenological Study of African American Female Leaders in Counselor Education. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.A. Contributions of Black psychology scholars to models of racism and health: Applying intersectionality to center Black women. Am. Psychol. 2023, 78, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.A. Discrimination: A Social Determinant of Health Inequities. 2020. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/discrimination-social-determinant-health-inequities (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Klonoff, E.A.; Landrine, H.; Campbell, R. Sexist Discrimination May Account for Well-Known Gender Differences in Psychiatric Symptoms. Psychol. Women Q. 2020, 24, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Subich, L.M. A Concomitant Examination of the Relations of Perceived Racist and Sexist Events to Psychological Distress for African American Women. Couns. Psychol. 2003, 31, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A.; Vu, C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54, 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, M.D.; Browning, W.R.; Hossain, M.; Clay, O.J. Vicarious experiences of major discrimination, anxiety symptoms, and mental health care utilization among Black Adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 316, 114997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, U.S.; Miller, E.R.; Hegde, R.R. Experiences of discrimination are associated with greater resting amygdala activity and functional connectivity. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korous, K.M.; Causadias, J.M.; Casper, D.M. Racial discrimination and cortisol output: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 193, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, D.J.; Ding, Y.; Hargreaves, M.; Van Ryn, M.; Phelan, S. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2008, 19, 894–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozada, F.T.; Jagers, R.J.; Smith, C.D.; Bañales, J.; Hope, E.C. Prosocial Behaviors of Black Adolescent Boys: An Application of a Sociopolitical Development Theory. J. Black Psychol. 2017, 43, 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A. Understanding political development through an intersectionality framework: Life stories of disability activists. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2016, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangri, S.S.; Jenkins, S.R. The University of Michigan class of 1967: The Women’s Life Paths Study. In Women’s Lives through Time: Educated American Women of the Twentieth Century; Hulbert, K.D., Schuster, D.T., Eds.; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 259–281. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versey, H.S.; Kakar, S.A.; John-Vanderpool, S.D.; Sanni, M.O.; Willems, P.S. Correlates of affective empathy, perspective taking, and generativity among a sample of adults. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 2474–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, L.E. Motivation for Collective Action: Group Consciousness as Mediator of Personality, Life Experiences, and Women’s Rights Activism. Political Psychol. 1999, 20, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, E.C.; Pender, K.N.; Riddick, K.N. Development and Validation of the Black Community Activism Orientation Scale. J. Black Psychol. 2019, 45, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-economic Status, Stress and Discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza, S.T. Latent Class Analysis for Developmental Research. Child Dev. Perspect. 2016, 10, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C.; Hoffman, M. Variable-Centered, Person-Centered, and Person-Specific Approaches. Organ. Res. Meth. 2018, 21, 846–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, D.A.; Lewis, J.B. poLCA: An R Package for Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 42, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, J.K. Latent class analysis of complex sample survey data: Application to dietary data: Comment. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2002, 97, 736–737. [Google Scholar]

- Celeux, G.; Soromenho, G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J. Classif. 1996, 13, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, R.Q.; Welch, J.C.; Kaya, A.E.; Yeung, J.G.; Obana, C.; Sharma, R.; Vernay, C.N.; Yee, S. The intersectionality framework and identity intersections in the Journal of Counseling Psychology and The Counseling Psychologist: A content analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, D. Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer. Am. J. Soc. 1986, 92, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.; Horowitz, J.; Mahl, B. On Views of Race and Inequality, Blacks and Whites Are Worlds Apart; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gillborn, D. Intersectionality, Critical Race Theory, and the Primacy of Racism: Race, Class, Gender, and Disability in Education. Qual. Inq. 2015, 21, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colen, C.G.; Ramey, D.M.; Cooksey, E.C.; Williams, D.R. Racial disparities in health among non poor African Americans and Hispanics: The role of acute and chronic discrimination. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 199, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.T.; Cogburn, C.D.; Williams, D.R. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 407–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B.L.; Harp, K.L.H.; Oser, C.B. Racial and Gender Discrimination in the Stress Process: Implications for African American Women’s Health and Well-Being. Sociol. Perspect. 2013, 56, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Villamor, I.; Ramani, R.S. MTurk Research: Review and Recommendations. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilf, S.; Maker Castro, E.; Gupta, K.G.; Wray-Lake, L. Shifting Culture and Minds: Immigrant-Origin Youth Building Critical Consciousness on Social Media. Youth Soc. 2022, 55, 1589–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, N.; Hoyt, L.T.; Maker Castro, E.; Cohen, A.K. Sociopolitical Influences in Early Emerging Adult College Students’ Pandemic-Related Civic Engagement. Emerg. Adulthood 2022, 10, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shodiya-Zeumault, S.; Aiello, M.; Hinger, C.L.; DeBlaere, C. “We Were Loving Warriors!”: A Content Analysis of Black Women’s Resistance Within Psychological Science. Psychol. Women Q. 2022, 46, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, E.C. Towards an Understanding of Civic Engagement and Civic Commitment among Black Early Adolescents. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Generation Citizen. (n.d.). Generation Citizen. Available online: https://www.generationcitizen.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- The Brotherhood Sister SOL | Educating, Organizing, and Training for Social Justice. (n.d.). The Brotherhood Sister SOL. Available online: https://brotherhood-sistersol.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Checkoway, B.; Allison, T.; Montoya, C. Youth Participation in Public Policy at the Municipal Level. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2005, 27, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.D.; Hunter, C.D. Counterspaces: A unit of analysis for understanding the role of settings in marginalized individuals’ adaptive responses to oppression. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grier-Reed, T.L. The African American student network: Creating sanctuaries and counterspaces for coping with racial microaggressions in higher education settings. J. Humanist. Couns. Educ. Dev. 2010, 49, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).