Abstract

Young adults are disproportionally affected by mental illnesses (MIs) and often encounter numerous obstacles to accessing healthcare. Untreated MIs have high chronicity and recurrence and are associated with worse health and life outcomes. The aim of the study described in this protocol is to characterize and better understand the barriers and facilitators to accessing mental healthcare for young adults with mental health-related disabilities (YMHDs), focusing on the impact of functional impairment, determinants of health, and unmet healthcare needs. The study protocol, guided by critical realism, uses a patient-oriented sequential mixed-methods design and involves patient research partners (PRPs) to ensure the voices and perspectives of those directly impacted are central to the research process. This study includes a quantitative analysis of secondary data from the Canadian Community Health Survey and a qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews with YMHDs. The data will be integrated by themes-by-statistics joint display. The study protocol follows the Tri-Agency Statement of Principles for data collection, storage, retention, sharing, and analysis, adheres to ethical guidelines to ensure participant confidentiality and informed consent, and has received institutional ethics approvals. This study will provide valuable insights into factors that act as barriers or facilitators to accessing care and inform the development of targeted interventions to improve access and support for YMHDs. This study has several strengths, including a participatory research approach that involves PRPs and other relevant stakeholders in the research process, a targeted focus on a specific age group, and the use of mixed-methods research and critical realism. This protocol describes a study that will inform policy, service delivery, and treatment options. This study has the potential to drive systemic change and significantly improve the lives and health of young people with mental health needs.

1. Introduction

Mental disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, are the leading contributors to years lived with disability and are the most significant contributor to disability in young people, with over 75% of mental disorders arising between early adolescence and young adulthood [1,2,3]. While there is no universally accepted age range for young adulthood [4], informed by theories such as Arnett’s emerging adulthood [5] and the millennial odyssey [6], the range of 18 to 30 years for young adults has been deemed appropriate both chronologically and developmentally. Despite the significant magnitude of this problem, leaders in disability research confirm that mental impairments—referred to in the literature as “hidden” disabilities—are less readily perceived as disabilities because the conditions are often unobservable and highly stigmatized, tend to fluctuate, are unapparent to outside observers, and defy the outward social construction of disability [7].

Other factors that impact young adults with mental health-related disabilities (YMHDs) are the critical developmental stages of adolescence and emerging adulthood for identity formation and self-acceptance [8,9]. The presence of a hidden disability can significantly hinder this process, leading to further negative outcomes. For YMHDs, day-to-day interaction with a non-disabled world exposes them to ableist, discriminatory, stigmatic, and oppressive social norms and values, which may become internalized [7].

Moreover, the interpersonal relationships of persons with a hidden disability are more strained than those of persons with visible disabilities due to the doubt and suspicion surrounding disability status. As YMHDs’ limitations are not immediately obvious, their struggles are assumed to be less real or difficult than those of people with more apparent disabilities. Thus, YMHDs are in a compounded situation of invisibility—mental illness and disability—and are subject to a multiplication of stigma, discrimination, oppression, and potential disbelief or dismissal of the severity or significance of their healthcare needs [10,11,12].

1.1. Aim

The urgent need to confront the disparities in youth mental health cannot be overstated. Untreated mental disorders often trigger a cascade of long-term negative consequences, highlighting the need for researchers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers to collaborate in championing equitable, accessible, and effective mental healthcare for all young people [13]. This protocol describes a study aimed at enhancing the lives of young adults with mental illness by examining the effects of mental health-related disabilities on access to healthcare services. This study carries practical significance for policymakers and healthcare providers as it seeks to pinpoint the specific obstacles and difficulties experienced by YMHDs.

The results of this study can lead to changes in funding priorities, service delivery models, and policy development, ultimately promoting inclusion, equity, and empowerment. Equally important, the resulting interventions and recommendations could bring about a paradigm shift in the approach to mental health, leading to the development of innovative treatments and interventions, such as the integration of self-directed models of access and artificial intelligence to optimize access to care and support self-management, potentially transforming mental healthcare.

1.2. Mixed-Methods Research Question

What is the relationship between determinants of health, functional impairments, and unmet healthcare needs for Canadian young adults with mental health-related disabilities, and how do these quantitative factors relate to their lived experiences, perceptions, and understandings of accessing healthcare?

1.3. Integrated Analysis Framework

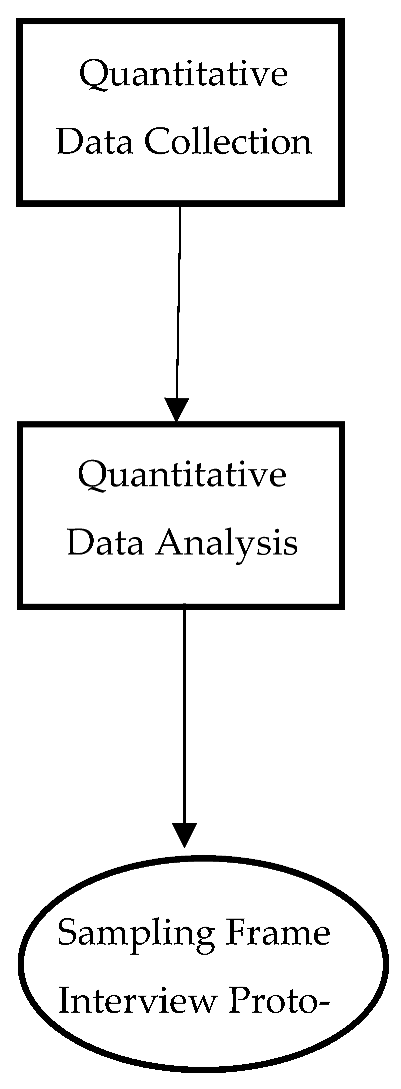

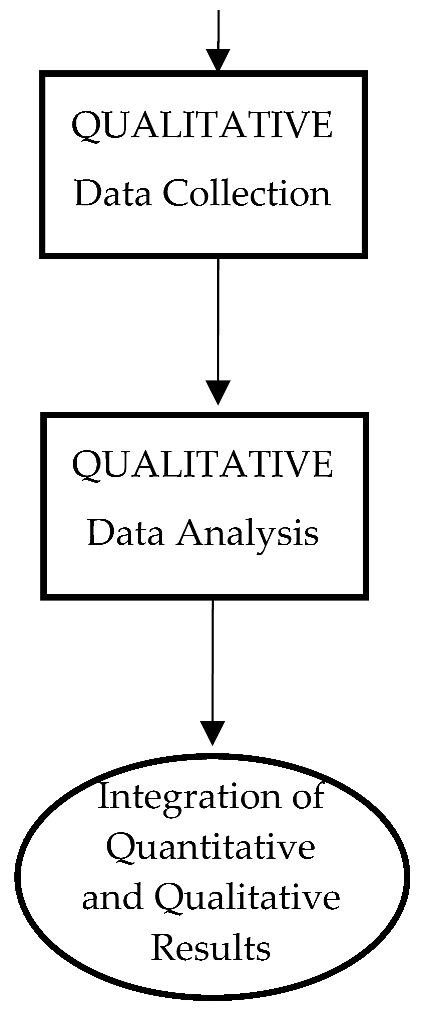

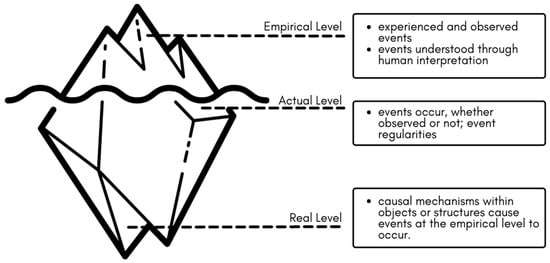

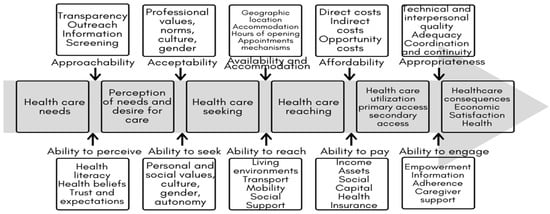

This protocol utilizes an integrated analysis framework (Figure 1) that considers the layered complexity of health system access, mental illness, mental health-related disability, and impairment. First, conducting research with YMHDs requires powerful tools to “see” the unseen and hidden. This protocol will use critical realism (CR), a theoretical framework that examines complex issues through three levels of reality: empirical, actual, and real (Figure 2). CR is viewed as having the unique potential to effectively frame, identify, and understand complex phenomena [14,15].

Figure 1.

Integrated analysis framework to guide data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results adapted from (Bhaskar [15] Levesque et al. [16]; WHO [17].

Figure 2.

Critical realism stratified reality/depth ontology, adapted from Bhaskar and Danermark [18]; Fletcher [19]; Porpora [20]; Vincent and O’Mahoney [21].

Second, this study will use the patient-centered definition and conceptual framework of access to healthcare (CFAH) developed by Canadian researchers Levesque et al. [16] (Figure 3). The CFAH presents a sophisticated model of healthcare access, defining it as the opportunity to identify, seek, reach, utilize, and ultimately benefit from appropriate healthcare services in situations of perceived need. The model operates on the interplay between supply-side and demand-side factors at each stage. Supply-side factors refer to the characteristics and distribution of healthcare services themselves, including their availability, affordability, and approachability. These aspects determine the ease with which services can be accessed by YMHDs. On the other hand, demand-side factors pertain to the personal attributes and circumstances of YMHDs seeking care, such as their ability to recognize health needs, financial capacity to seek treatment, and physical and psychological readiness to engage with healthcare systems.

Figure 3.

Levesque et al. [16], conceptual framework of access to healthcare.

Finally, the framework includes the environmental factors, such as determinants of health, that make up the physical, social, and attitudinal environment in which YMHDs live and conduct their lives, captured by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health [22]. The integrated analysis framework will be used as the scaffolding for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

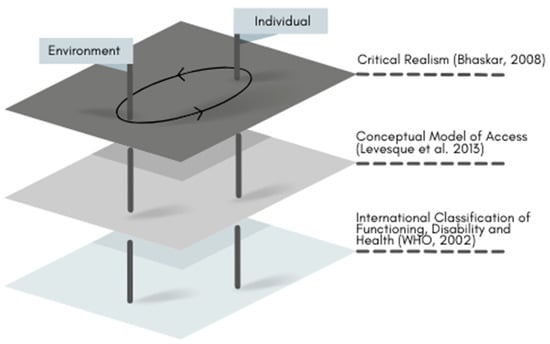

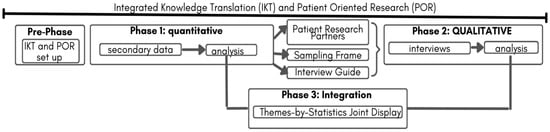

This protocol uses a patient-oriented sequential mixed-methods study design (Figure 4). Patient-oriented research (POR) involves individuals with personal health experiences as partners in the research process [23]. Involving YMHDs as patient research partners (PRPs) is an innovative and important piece of the protocol that ensures that the voices and perspectives of those directly impacted by the research are central to the research process.

Figure 4.

Patient-oriented mixed-methods sequential explanatory design.

POR recognizes that YMHDs have unique needs and experiences in accessing healthcare, and involving them as partners can lead to more relevant and effective research outcomes while destigmatizing mental illness and mental health-related disabilities, thus promoting inclusion and empowerment and creating a more equitable and patient-centered healthcare system.

By utilizing sequential mixed methods, both quantitative and qualitative data can be integrated through CR’s intensive and extensive methods. This approach ensures that there are no methodological inconsistencies or paradigmatic slurring and leads to a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem [19,20].

2.2. Pre-Phase: POR and Integrated Knowledge Translation

Phase 1 was shaped by input from existing youth advisory councils. Six young adult advisory councils, which consisted of 35 youth participants, were involved in the process of informing the design, implementation, recruitment strategies, and knowledge translation approaches to ensure relevance to YMHDs. Structures for integrated knowledge translation will be formalized to partner with potential knowledge users (KUs) such as health system funders, policy analysts, clinicians, and program architects. KU participation and feedback will be incorporated systematically through the use of technology, and clear communication channels will be established to ensure KUs are kept informed and involved throughout the research process [24].

2.3. Phase 1: Quantitative Extensive Data

2.3.1. Research Question

What is the association between functional impairments and unmet healthcare needs among Canadian young adults aged 18–30 years with mental illness, and how do demographic factors and determinants of health modify this association?

H1: Mid- to high-functional impairments will be associated with more unmet healthcare needs among Canadian young adults aged 18–30 years with mental illness compared to young adults with no mental illness. This association will be modified by demographic factors and determinants of health.

2.3.2. Sample and Measures

This study will use the 2018 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) annual microdata, file reference period 2 January 2018 to 24 December, with a stratified sample and a cross-sectional design [25]. The CCHS collects information related to health status, impairment, distress, disability, healthcare utilization, and health determinants, surveying approximately 130,000 Canadian respondents aged 12 or older residing in households in all provinces and territories, and is designed to provide reliable estimates at the health region level every two years. The CCHS 2017–2018 is the most current comprehensive national dataset for examining the variables of interest. We acknowledge this predates the COVID-19 pandemic and thus will specifically address pandemic-related questions in Phase 2.

The exclusion criteria include persons living on reserves and other Indigenous settlements in the provinces; full-time members of the Canadian Forces; the institutionalized population; children aged 12–17 that are living in foster care; and persons living in the Quebec health regions of Région du Nunavik and Région des Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James, who represent less than 3% of the Canadian population aged 12 and over. The quality of estimates produced with CCHS data is measured with the coefficient of variation (CV), produced using bootstrap weights. The CCHS employs a sophisticated weighting process to ensure its data reflect the Canadian population accurately. Each participant is assigned a survey weight, representing the number of individuals in the overall population the respondent’s data is meant to represent. This methodological rigor facilitates the reliable estimation of health statuses and trends across various demographics, ensuring the data are representative at both the provincial and national levels. A detailed description of the survey methodology is provided on the Statistics Canada website [25]. The questionnaire is voluntary, available in both official languages, and can be completed by interview in either English or French. The variable measures are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Canadian Community Health Survey measures list [25].

2.3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

STATA version 17 will be used to perform the data analysis. First, the data would be cleaned, transformed, and recoded. The analysis would be conducted in two stages: first, descriptive statistics, then inferential with the recommended replicate bootstrap weighting procedure used in all analyses. The proposed analysis plan is based on nominal data (categorical factors) and dichotomous (binary) data.

In the first stage, measures of central tendency and frequency distributions of selected independent variables, based on the integrated analysis framework, would be computed by unmet needs in a sample of young adults aged 18 to 30. The age range is identified by the literature as the population at highest risk. Then, selected mental health-related disability measures (e.g., participation, cognition, self-care) will be cross-tabulated with unmet healthcare needs. To ensure compatibility with the replicate bootstrap weighting procedure, Wald tests associated with a logistic regression model will be used to assess the significance of the bivariate association, and the strength of the association will be quantified using the crude odds ratio. This part of the study is descriptive.

In the second stage, a series of binary logistic regressions that includes covariates and associated interaction terms will be used to assess effect modification and confounding. Wald tests for the interaction terms will assess effect modification, and a comparison of crude to adjusted odds ratios will be used to assess confounding.

Long [26] suggests that sample sizes of less than 100 should be avoided and that 500 observations should be adequate for these types of statistical analysis. Binary logistic regression modeling is proposed as it is among the most frequently used approaches for developing multivariable models for binary outcomes [27,28]. Linearity will likely not need to be checked to ensure that the predictor variables are linearly related to the log of the dependent variable, as all predictor variables are categorical. However, the assumption of multicollinearity will need to be evaluated using variance inflation factors.

Data Integration: The first integration of Phase 1 data will inform Phase 2 recruitment guidelines, the appropriate PRPs (Table 2) to engage, and the interview guide questions (Table 3).

Table 2.

Sample template for participant selection: joint display.

Table 3.

Sample template for interview questions: joint display.

2.4. Phase 2: Qualitative Intensive Study

2.4.1. Research Questions:

- What are the experiences and perceptions of YMHDs regarding access to mental healthcare?

- How do YMHDs perceive the impact of functional impairments on their access to mental healthcare?

- How do demographic factors and determinants of health shape the experiences and perceptions of YMHDs regarding access to mental healthcare?

- What do young adults perceive as barriers and facilitators to accessing mental healthcare for YMHDs?

2.4.2. Sample

Recruitment

Participants for this study will be recruited from a provincial health services clinical registry. This registry includes individuals who have utilized the healthcare system and have pre-consented to participate in research studies. While the sample will be determined by the Phase 1 sampling frame included here is general criteria, inclusion criteria: 18 to 30 years old, current or former diagnosis of mood and/or anxiety disorder, experience with the health system, English speaking or able to access translation support, not in active treatment.

Ethical concerns led to the decision to recruit participants with some distance from treatment. However, it is recognized that recovery from mental illness is a long and ill-defined process; thus, allowing participants to self-define themselves as recovered or “on the road to recovery” feels respectful of participants’ autonomy. Exclusion criteria: unable to consent, which includes intellectual disabilities, fluctuating capacity, or other reasons where individuals may not have decision-making capacity at the time of the study.

2.4.3. Sample Size

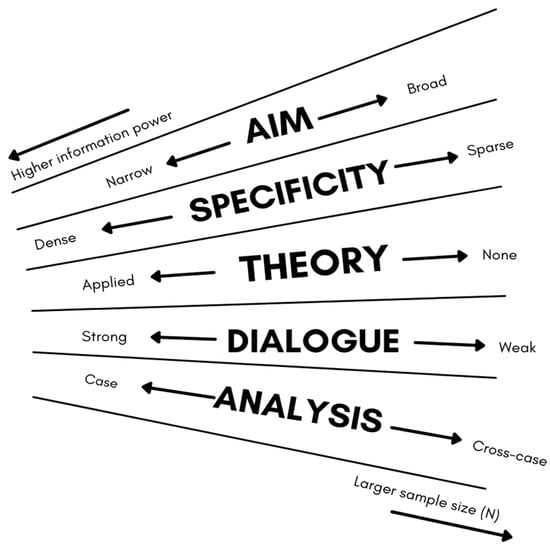

The sample size will be determined from information power [29] (Figure 5) where 6–10 participants are deemed an appropriate sample size to explore individual experiences and themes/patterns across the group as a whole.

Figure 5.

Information power items and dimensions, adapted from Malterud et al. [29].

2.4.4. Data Collection

A semi-structured interview schedule will be developed from Phase 1, supported by the literature and PRPs, to ensure that both the unique experiences and beliefs of each participant are heard and that the research questions are addressed. Potential types of anticipated questions include:

- “Can you think back to the times when you didn’t get the healthcare you needed? Why do you think that happened?”

- “What troubles do you run into when trying to look after your health because you have trouble remembering things or staying focused?”

- “Have there been times when you think your trouble with memory or focusing, and feeling anxious, stopped you from getting healthcare? Tell me about that.”

Participants can choose the location and format of their interview, which may enhance feelings of safety and control. Interviews will be conducted by an experienced registered psychotherapist, lasting 60–90 min. Participants will receive therapeutic resources before and after the interview. Audio recording and orthographic transcription will be conducted using a digital voice recorder if face-to-face or by phone, and university-approved virtual software if online.

2.4.5. Data Analysis

Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) [30] was chosen for its emphasis on thematic patterning and not idiographic meaning alongside its flexible theoretical and analytic scope aligning with CR. RTA allows for the participants’ experiences to be treated as real and true to them, yet inextricably mediated and shaped at the intersections of environmental factors. The analysis process begins during the interview phase, with individual transcripts analyzed using NVivo 11 in an iterative and recursive manner to ensure quality and rigor.

The study protocol will employ CR’s retroductive and retrodictive approach [31,32,33,34,35] to extend the common deductive and inductive methods. PRPs will be invited to partner in the analysis; to facilitate meaningful engagement, data will be organized in advance to encourage PRP development of new insights. Quality practices in RTA prioritize the researcher’s depth of engagement and reflexive practice, rather than measures of intercoder agreement. Braun and Clarke’s [36] tool for evaluating RTA, which includes 20 evaluation questions, will be used to assess the RTA analysis and write-up.

2.5. Phase 3: Integration of Data Themes by Joint Display

The Phase 1 and Phase 2 data will be integrated by themes-by-statistics joint display [37,38]. The themes-by-statistics integration approach aims to improve the validity and reliability of mixed-methods research by providing a more comprehensive understanding of the research question or problem being studied. This approach involves comparing and contrasting themes or patterns identified in the qualitative data with statistical findings from the quantitative data to identify relationships or discrepancies between them. To achieve this integration, a joint display is created, which consists of a table or matrix that visually displays the themes or patterns from the qualitative data and the statistical findings from the quantitative data side by side.

2.5.1. Data Management and Storage

The study protocol follows the Tri-Agency Statement of Principles on data management [39] and includes a comprehensive data management plan that adheres to ethical guidelines for data collection, storage, retention, sharing, and analysis. The plan prioritizes participant confidentiality and informed consent, while ensuring the data are stored securely and backed up regularly. All participant data will be deidentified before sharing with the PRPs for analysis and feedback.

2.5.2. Ethical Considerations

This study protocol has received institutional ethics approvals (REB22-1063). Guillemin and Gillam [40] draw a distinction between “procedural ethics”, which involves seeking approval from relevant ethics committees, and “ethics in practice”, or the everyday ethical issues that arise in conducting research. POR and integrated knowledge translation approaches ensure that ethics in practice will remain at the forefront.

2.5.3. Informed Consent

Prospective participants will be provided with a detailed explanation of this study and asked to sign a consent form indicating their willingness to participate. The consent form will include information about the purpose of this study, the procedures that will be involved, and any potential risks or benefits. Participants will also be informed that participation is voluntary and that they can withdraw at any time without penalty.

Confidentiality and privacy will be protected throughout the study. All participant data will be stored securely and will only be accessible to members of the research team. Participants’ identities will be protected by the use of participant codes or pseudonyms. Any personal identifying information, such as name or contact information, will be kept separate from the study data.

Participants will be informed of the limitations of confidentiality during the informed consent process in the event that a participant expresses intent to harm themselves or others. However, the research team will take all necessary steps to protect the participant’s privacy and dignity while ensuring their safety.

2.5.4. Risk–Benefit Analysis

The Kipnis model [41,42,43] will be utilized to assess vulnerability and methods to remedy them and an adapted version of Rid et al.’s [44] Magnitude of Harm Scale to assess potential risks prior to study commencement and through to study completion (Table 4). Participatory research assumes reciprocity between researcher and participant; as such, it is the duty of the study to provide some benefit in return for the participant’s efforts. The study protocol looks to provide the following benefits (Table 5).

Table 4.

Magnitude of Harm Scale, adapted from Rid et al. [44].

Table 5.

Potential benefits for participants, adapted from Sieber [43].

3. Anticipated Results

This research will investigate the relationship between determinants of health, functional impairments, unmet healthcare needs, access to mental healthcare for YMHDs, and how these factors relate to their lived experiences and perceptions of accessing healthcare. The results will provide valuable insights into which factors act as barriers or facilitators to accessing care and can inform the development of targeted interventions to improve access and support for young adults.

Phase 1: It is anticipated that YMHDs with higher levels of functional impairments will report more unmet healthcare needs and less access to care, even after adjusting for demographic factors and determinants of health. This study also anticipates that age, gender, income, education, and geographic location will significantly affect access to care for YMHDs.

Phase 2: It is anticipated that interviews with YMHDs will highlight a range of systemic and personal factors that contribute to the treatment gap and limited access to mental health services. This study also expects to gain insights into the effectiveness of current service delivery models and identify areas for improvement. The integrated findings will inform recommendations for policy changes and service delivery improvements to address the treatment gap and improve access to mental health services for YMHDs.

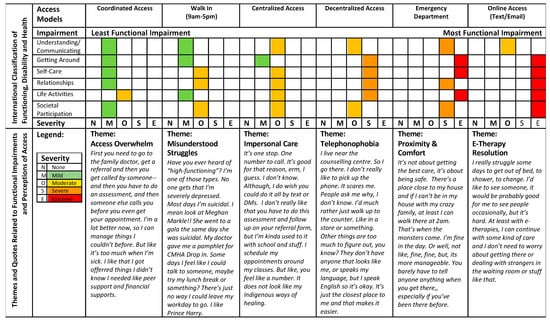

Phase 3: Figure 6 provides an example of the potential integration of quantitative and qualitative data.

Figure 6.

Example of themes-by-statistics joint display organized by severity of functional impairments (quantitative data) mapped to access models recoded to the functions required to utilize the program/service and the perceptions and experiences of YMHDs (qualitative data).

4. Strengths and Limitations

This study protocol has several strengths to ensure its relevance and applicability. The protocol involves YMHDs as partners and other relevant stakeholders in the research process, ensuring that their lived experiences and perspectives inform the study protocol and process. By doing so, the approach can lead to more patient-centered interventions and policies, and the involvement of YMHD partners in the analysis can enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of this study’s results.

This study’s targeted focus on YMHDs aged 18–30 allows for a specific understanding of access and addresses a gap in the literature, providing tangible insights for policy and practice changes. The use of a sequential mixed-methods design, buttressed by CR, allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the research questions, aims, and objectives. The protocol also avails itself of the use of secondary data to reduce the time associated with collecting primary data and rolling analysis of qualitative data to manage the workload for the researchers and PRPs.

The use of mixed-methods research provides methodological flexibility for the integration of quantitative and qualitative data, offering a more nuanced understanding of the research question. Multiple methods and data sources can also increase the validity of the research findings. Finally, CR provides several strengths, including epistemological diversity, allowing for the integration of subjective experiences and objective realities to provide a more complete understanding of MHDs and access. CR offers a nuanced understanding of causality by acknowledging that social phenomena are influenced by various social, cultural, economic, and historical factors, seeking to identify the underlying mechanisms and structures that contribute to observable outcomes while also recognizing the importance of context and contingency. CR offers a more complex and nuanced interpretation of causality compared to more traditional research paradigms.

While this study protocol has many strengths, there are also limitations and challenges to consider upon replication. The mixed-methods research approach may pose challenges for managing and integrating qualitative and quantitative data and the sequential design may result in lengthy timeframes for data collection and analysis. Challenges may arise in recruiting and engaging young adult participants, such as building trust, maintaining confidentiality, and addressing potential stigmatization associated with mental health.

Moreover, the measures used in the Canadian Community Health Survey may not capture all relevant mental health-related disability information and certain populations are also excluded from the survey, noted above, limiting the transferability of the findings. Finally, the scope of the research question and the available resources, including time and funding, also pose limitations.

5. Timeline

Table 6 provides an example timeline of the protocol.

Table 6.

Example timeline of a patient-oriented sequential mmple timeline of a patient-oriented sequential mixed-methods study.

6. Budget

Table 7 provides a proposed budget for the study.

Table 7.

Proposed budget for patient-oriented sequential mixed-methods study.

7. Conclusions and Implications

This study protocol represents a significant contribution to the field of youth mental health research, as it purposefully integrates critical realism, mixed methods, patient-oriented research, and integrated knowledge translation to generate comprehensive and nuanced interpretations of the complex phenomena being studied. Through a participatory research approach that includes YMHDs as partners, this protocol offers an innovative avenue to improve the relevance, applicability, and impact of research findings.

The potential implications of this study extend beyond the immediate population and context, enabling researchers to explore the underlying structures and mechanisms that shape social reality and influence health outcomes. By informing policy, service delivery, and treatment options, this protocol has the potential to drive systemic change and significantly improve the lives and health of young people with mental health needs. This study protocol represents a model for future research initiatives in the field of youth mental health, with the potential to inspire similar impactful initiatives and progress in the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.; methodology, All; validation, All; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.; writing—review and editing, All; supervision, G.D. and S.B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol has received institutional ethics approvals (REB22-1063) by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (CHREB) at the University of Calgary. The CHREB is constituted and operates in compliance with the requirements and policies of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (current version); the International Conference on Harmonization—Good Clinical Practice Guideline (current version); the Health Information Act, R.S.A., 2000 c. H-5; and the Food and Drugs Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. F-27.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent will be obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. As this is a protocol paper, there is no data that is collected because the study has not been completed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chaudhury, P.K.; Deka, K.; Chetia, D. Disability associated with mental disorders. Indian J. Psychiatry 2006, 48, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Survey on Disability. 2017. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2019005-eng.htm (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Wiens, K.; Bhattarai, A.; Pedram, P.; Dores, A.; Williams, J.; Bulloch, A.; Patten, S. A growing need for youth mental health services in Canada: Examining trends in youth mental health from 2011 to 2018. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Young Adult Health and Well-Being: A Position Statement of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2017, 60, 758–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore, K.J.; Meersand, P. The Little Book of Child and Adolescent Development; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-989922-7. [Google Scholar]

- Valeras, A. “We don’t have a box”: Understanding Hidden Disability Identity Utilizing Narrative Research Methodology. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2010, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, D.S.; Burcaw, S. Disability identity: Exploring narrative accounts of disability. Rehabil. Psychol. 2013, 58, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Baillie, L. Usher Syndrome, an Unseen/Hidden Disability: A Phenomenological Study of Adults across the Lifespan Living in England. Disabil. Soc. 2022, 37, 1636–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, S. Out of the frame: Disability and the body in the writings of Karl Marx. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2017, 19, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, D. Dis/entangling critical disability studies. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanebutt, R.; Mueller, C. Disability Studies, Crip Theory, and Education. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-1392 (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Malla, A.; Shah, J.; Iyer, S.; Boksa, P.; Joober, R.; Andersson, N.; Lal, S.; Fuhrer, R. Youth Mental Health Should Be a Top Priority for Health Care in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. Explaining Society: An Introduction to Critical Realism in the Social Sciences, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. A Realist Theory of Science; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health; The international Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organizatioin: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar, R.; Danermark, B. Metatheory, Interdisciplinarity and Disability Research: A Critical Realist Perspective. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2006, 8, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.J. Applying Critical Realism in Qualitative Research: Methodology Meets Method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpora, D.V. Reconstructing Sociology: The Critical Realist Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, S.; O’Mahoney, J. Critical Realism and Qualitative Research: An Introductory Overview. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods: History and Traditions; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2018; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustün, T.B.; Chatterji, S.; Bickenbach, J.; Kostanjsek, N.; Schneider, M. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: A new tool for understanding disability and health. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research—Patient Engagement Framework—CIHR. Available online: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Gagliardi, A.R.; Berta, W.; Kothari, A.; Boyko, J.; Urquhart, R. Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: A scoping review. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada Canadian Community Health Survey—Annual Component (CCHS). Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=795204 (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Long, S. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables; Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bujang, M.A.; Sa’at, N.; Sidik, T.M.I.T.A.B.; Joo, L.C. Sample Size Guidelines for Logistic Regression from Observational Studies with Large Population: Emphasis on the Accuracy Between Statistics and Parameters Based on Real Life Clinical Data. Malays. J. Med. Sci. MJMS 2018, 25, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Smeden, M.; Moons, K.G.; de Groot, J.A.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Reitsma, J.B. Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2019, 28, 2455–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P.K.; O’Mahoney, J.; Vincent, S. Critical Realism and Mixed Methods Research. In Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism; Edwards, P.K., O’Mahoney, J., Vincent, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariadis, M.; Scott, S.; Barrett, M. Methodological Implications of Critical Realism for Mixed-Methods Research. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 855–879. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43826004 (accessed on 17 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Mukumbang, F.C. Retroductive Theorizing: A Contribution of Critical Realism to Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2021, 17, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, D. Some implications of critical realism for mental health research. Soc. Theory Health 2014, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, D. Critical realism and mental health research. In Routledge International Handbook of Critical Mental Health; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T.C. Descriptions of Sampling Practices within Five Approaches to Qualitative Research in Education and the Health Sciences. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2015, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.E.; Grove, A.L.; Clarke, A. Pillar Integration Process: A Joint Display Technique to Integrate Data in Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2019, 13, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, I. Tri-Agency Research Data Management Policy. Available online: https://science.gc.ca/site/science/en/interagency-research-funding/policies-and-guidelines/research-data-management/tri-agency-research-data-management-policy (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Guillemin, M.; Gillam, L. Ethics, Reflexivity, and “Ethically Important Moments” in Research. Qual. Inq. 2004, 10, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipnis, K. Seven Vulnerabilities in the Pediatric Research Subject. Theor. Med. Bioeth. 2003, 24, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipnis, K. Vulnerability in Research Subjects: A Bioethical Taxonomy; Commissioned Papers: Rockville, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sieber, J. Planning Ethically Responsible Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rid, A.; Emanuel, E.J.; Wendler, D. Evaluating the risks of clinical research. JAMA 2010, 304, 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCambridge, J.; Witton, J.; Elbourne, D.R. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).