1. Beginnings

Before you hear the story of our project, we invite you to take a moment to reflect on your own wellbeing. If you painted it, what would it look like? What colors, shapes, textures would it take? If you heard it in a song, what would it sound like? What lyrics or rhythms do you hear? As you live in your body, what sensations are elicited when you think about your wellbeing?

Meditating on these questions, you have obtained a first taste of how our own collective research process grew into a multisensory engagement with the question of wellbeing amongst Latine youth. In this paper, we describe the first phase of an intergenerational participatory action research project exploring how Latine youth and young adults in the U.S. understand wellbeing. It represents a slice of a larger national project measuring youth and young adult perspectives across three racial/ethnic affinity groups on the concept of wellbeing.

As a multi-voiced, collaboratively constructed piece, this writing will move between first and third person, hosting both collective or “we” experiences, as well as individual ones, with members narrating their personal accounts. In keeping with our commitments to collective wellbeing, we focus on process as well as product: wellbeing should be centered not only in what we study, but how we study it and with whom. Following a principle of using a creative praxis, we also embrace multiple forms of expression; we move between poetry and prose, visual and performing arts, and academic writing in this article. First, we situate our work in the broader literature of wellness, wellbeing and mental health.

2. Wellness, Wellbeing and Bienestar

Wellbeing and wellness are concepts receiving much scholarly attention. They are distinct yet interconnected constructs, where “wellness is a process (people embark on a path of wellness) and wellbeing is a state at any given point in time (at the end of the path are degrees of being well)” [

1]. However, in the literature, they are often used interchangeably, and as such, will be similarly referenced in this paper, though the focus here is on wellbeing. Measures of wellbeing examine multiple dimensions of an individual state or sense of personal satisfaction. Two of the most popular wellness metrics, Satisfaction with Life Scale and Scale of Psychological wellbeing, “support the view that wellbeing at its core is an individualistic process of contentment, satisfaction, or happiness derived from optimal functioning” [

2]. Another popular scale, I COPPE (Interpersonal, Community, Occupational, Physical, Psychological, Economic) is based on Prilleltensky’s framing of wellbeing “as a positive state of affairs in one’s life”, measuring this perception both in an overall sense as well as within multiple domains [

3]. These domains include satisfaction with interpersonal relationships with family and friends, the neighborhood or community people live in, their work or employment situation, their physical health, their emotional health, and their financial conditions [

3]. In their review spanning ten years of the family and consumer science literature on wellness and wellbeing, Kihm and McGregor identified nine areas consisting of emotional, social, spiritual, political, environmental, physical, economic or financial, occupational and intellectual domains [

1]. Noting that occupational, intellectual, and political domains are understudied, they joined the call for a more nuanced treatment and conceptualization of wellbeing.

Across these dimensions, one commonality is the framing of wellbeing and wellness as individualistic, internal states or processes [

2]. Wellbeing within communities of color can take a more relational and holistic approach considering multiple factors, including the individual within the context of the larger community they are a part of [

3,

4]. Fulfillment, happiness and achievement are relational (for example, for the family or community) rather than individual accomplishments [

3,

5]. In a qualitative study of immigrant Latinx adults, Rojas Perez and colleagues [

3] examined psychosociocultural dimensions of wellbeing/bienestar. They identified general themes of wellbeing across psychological, social and cultural dimensions. Specifically, they defined the psychological dimension of what they termed tranquilidad interconectada or interconnected tranquility as an individual feature nested in the social, such that participants found inner tranquility in knowing their loved ones were safe and well. The social component was described as “convivir con los demas”, or the ability to share their lives in harmony with others. Within the cultural dimension, they discussed the central roles of family responsibility and connection to spirituality, specifically the relationship to God and faith. Finally, they added a dimension of physical health, also in connection to its role in serving self and family wellbeing. Across these areas, wellbeing for Latines was rooted in and connected to relational and community-level concerns. This relational focus is also reflected in the oft-cited cultural characteristic of familismo.

Among Latine communities, familia emerges as a critical component of wellbeing. Familismo, a cultural-value-centering family, has been consistently demonstrated to be a supportive factor in terms of meeting social, material and emotional needs [

3,

6,

7]. Its most protective factors feature reciprocity, unconditional support, and collectivism [

6]. However, some scholars [

6,

8] argue that the relationship between familia and wellbeing is more complex than is often depicted in Latine communities. Caro and colleagues [

8] found that though family were “indispensable for maintaining emotional health”, they also presented as sources of stress. Specifically, worries over family members, particularly in transnational contexts, and conflict with family were significant stressors, in part because of how strongly valued these relationships are. Patron [

6] adds that for LGTBQ+ Latine, “precarious familism” may more accurately describe the disparate experiences of acceptance and rejection from family members. One outcome is that “familismo may diminish queer Latino sexuality in favor of familial ties” [

6]. There can also be distancing or even exit from the family (in the form of migration for example), further potentially alienating them from their supportive aspects [

6,

8]. Not simply a cultural feature, these dynamics are understood as being situated within a larger patriarchal framework within systems of interlocking oppressions [

6].

Critical scholars argue for conceptualizations of wellbeing that situate it within an ecological and intersectional context, taking into account the role of power, oppression and liberation [

9,

10,

11]. Personal wellbeing is shaped by structural conditions, and is tied to family and community wellbeing within a broader ecological frame [

9]. In order to achieve a fuller understanding of wellbeing, particularly for communities of color, it is important to attend to relations of power and the context of White supremacy, xenophobia, heteropatriarchy and racial capitalism [

9,

10,

11,

12]. For communities of color, the historical impact of these structural oppressions has been articulated through intergenerational trauma. The next section will focus on trauma, mental health and healing in connection to wellbeing.

3. Mental Health, Trauma and Healing

When considering the field of mental health, we see that there are disparities in access, use, representation and cultural responsiveness. For instance, the 2019 American Psychological Association data found that 83% of the US psychology workforce was White, and in 2022, the Bureau of Labor Statistics similarly found that 82.4% of all mental health counselors were White. The lack of cultural diversity within the mental health/wellness arena is a testament to “a field that has historically neglected the needs and concerns of minority groups” [

13]. Even when services are available, “retention, attendance, and success rates tend to be low” among the Latine community [

10]. Some authors believe that the low success/utilization of mental health services within the Latine community reflects a rejection of the White supremacist notion that to be “well” requires a denial of one’s cultural identity, traditions, and experiences of systemic oppression [

12].

The lack of diversity within the wellness field has also contributed to a definition and practice of wellness that does not take the holistic, collective orientations of people of color, nor their experiences of oppression seriously [

12]. Minsky-Kelly and Hornung [

12] discuss this as “structural whiteness in the framing of mental health”, offering as an example that intergenerational racial and colonial violence does not meet the threshold for trauma in a way that is eligible for mental health services. They also argue that traditional counseling approaches are based on White/Western views of wellness that are individualistic, episodic, and internal to the person, with solutions involving medical or cognitive interventions. Some notions of self-care can also fall under this framing, as Okello and colleagues [

11] argue, because of its consumerist (you need to be able to afford to engage it), individualist, whitestream-framing, and temporary nature, as the underlying structures creating the need for it remain. As such, these approaches fail to meaningfully engage people’s experiences with systemic injustice, including racial battle fatigue, intergenerational, and migration trauma [

11,

12,

14].

Moving away from medical models of wellness and wellbeing, scholars have discussed the ways in which BIPOC communities use healing-centered engagement [

15] rooted in artistic and cultural practices. Engaging in creative productions, such as music, dance, theater and other body work can be mechanisms of both personal healing from trauma and social change [

13,

16,

17,

18]. Minsky-Kelly and Hornung explain that such creative and embodied activities can heal by “help[ing] rebuild rhythmic systems of engagement that are disrupted by trauma through cultural practices involving song and dance” [

12]. Personal transformation and healing with and through collective work [

16] is a theme in some of the literature, where liberation from oppressive structures is both the process and goal of wellness [

10,

11,

16,

18]. Okello et al. [

11], posit that self-definition in the context of White supremacy, is itself a healing act, one of “resistance and liberation” [

11]. Similarly, Mayorga discusses the work of conocimiento with Latine youth, adopting Anzaldua’s term to describe a “process of ongoing self-examination and consciousness-raising” based on her “ theory of consciousness in motion, where the inner life of the mind and spirit is connected to the outer worlds of action with the struggle for social change” [

10]. The role of historical memory is discussed by both authors and integrated into Caro et al.’s [

8] model of healing they term HEART (Healing Ethno-Racial Trauma). In their model, both symptoms and systems of trauma and oppression are addressed in the healing of Latine immigrants, where problems are situated within its socio-historical context, there is recovery and reconnection to ancestral wisdom and historical memory, and oppression is operationalized as a “collective assault that needs collective action”. Taken together, this literature suggests that collective framings, creative actions, community care, conocimiento (which involves contextualizing and historicizing of the conditions of one’s wellness), and liberation can be features and goals of wellbeing for Latine youth.

5. Methods

5.1. Forging the Latine Bienestar Collective

As part of a larger grant-funded, multiphase initiative studying youth/young adult understandings of Latine wellbeing, an intergenerational group of six Latines (ages 22–46 at the time of the study) were brought together to form an affinity-based collective. This project is part of a larger initiative on Youth and Young Adult wellbeing organized by the Aspen Institute’s Forum for Community Solutions and Fresh Tracks. (See also ref. [

20]). Hailing from Colorado, the New York/New Jersey metropolitan area, and Washington state, the collective, eventually naming themselves Latine Bienestar, met regularly over Zoom over the period of a year for the first phase of the study. Two of us identify as cisgender men and three as cisgender women who originate or are descended from Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba/Ecuador and Peru. One of our youth designers also identifies as Afro-Latino. We range in fluency of our native tongues (Spanish), education, immigration status and ages. Two members of the collective (Jennifer and Jose) are referred to as the research navigators; one is a university professor and is the director of a center for undocumented students, and the other, at the time of this study, was a Department of Education administrator and doctoral student. The three young adult members of the Phase One research design team (Alexia and Israel, with Desiree as the peer research mentor) work as community leaders and organizers, researchers, and artists.

In order to have a common grounding of the issues and methods, the team joined two other affinity groups self-labeled as Black Expressions and AIAN (American Indian/Alaska Native) Wellbeing, in a series of quarterly whole-group virtual workshops in 2021. These sessions ranged from 2 h to half days and consisted of training in theories of participatory action research, data collection strategies, writing research protocols and questioning types. Later sessions covered approaches to analyzing qualitative data, such as through the Dedoose data analysis platform. Between whole-group sessions, the Latine Bienestar team would meet, at times weekly, over Zoom to develop our group’s region-specific research strategies. Our youth/young adult research team members then implemented these strategies in conducting their own research in their local communities.

Part of our process involved routines of intention. For example, we would begin each meeting with a check-in and opening question. Sometimes, we practiced breathing and meditation together, sharing our emotions through words or silent tears. On weeks that we did not meet synchronously, alternating team members would ask a question or share a video, song or meme through a group chat. Once, we even had a “onesie” day where everyone wore their pajamas on screen. This was important community building and community wellbeing work; it was our way of finding joy and connection in a virtual space during the time of the pandemic. At one point, four out of the five team members contracted COVID-19 and commiserated on the experience. We were there for each other and gave each other space in times it was needed, always with the support of the larger collective.

5.2. Study Design

These practices were aligned with elements of a Critical Participatory Action Research [

18,

19] and PAR EntreMundos [

21,

22], based on Anzaldúan notions of living between worlds. First, PAR projects embrace an approach to research where those most impacted by an issue are at the center of its study design and implementation, what makes research participatory [

18,

19]. As this was a study about Latine young adult wellbeing, the core group of three Latine young adult members of the intergenerational research team were deeply involved in decision making through all aspects of the research process, from framing the issues, to co-developing interview questions, recruiting and interviewing participants, analyzing and making meaning of the interviews, deciding on and carrying out presentations and other creative productions. In keeping with the larger group’s commitment to value youth/young adult time and labor as co-researchers, they, and not just the research navigators, received stipends for their work.

Other principles of a PAR Entremundos approach used in this study involved (1) creative praxis, where different parts of the research process are integrated with cultural and artistic expressions [

16,

17,

22]; (2) the concept of “power with/in”, drawn from eco-feminist Starhawk defined in a PAR context as attending to the relational aspects of collective work and the power dynamics they are situated within; and (3) indigenous cosmologies, where spirituality and healing work are named as part of the research process [

22]. In this study, the research team, as described above, consisted of an intergenerational group of Latine who centered their young adult members as this was the focus of the research. Throughout the training process and in the methods used, arts were deeply integrated in the form of music, painting, and poetry. The collective and healing processes described earlier were part of our commitments and also reflect the final two principles.

For this phase of the research (Phase 1), the collective decided that qualitative methods were most appropriate to explore the question of how Latine young adults understand wellbeing. As a group, we developed a common protocol made up of a set of inquiry areas with open-ended prompts, check-ins with participants during the interview about where the questions were landing on their bodies, and a closing breathing exercise followed by a list of online mental health resources. Participants were given $50 e-cards for the gift of their participation after interviews were completed. Interview questions were developed in sessions where research team members reflected on their own experiences and observations in writing, discussion and art-based prompts as part of larger brainstorming sessions led by the Fresh Tracks/Aspen Community Forum for Solutions teams. Based on the material generated in these sessions, research team members synthesized then narrowed down a set of seven common inquiry areas. Inquiry areas consisted of the following: framing wellbeing (What comes to mind when you think of wellbeing?), physical, financial and emotional health (How much do you feel like you -or people in your community- can afford to make the healthy choices you want?), identity (What are some ways you connect with your language and culture?), family (What are some of your family responsibilities?), spirituality (What are the ways spirituality has impacted your wellbeing, good or bad?) and community and social change (How do you feel that your community and local government impacts wellbeing?), and wellbeing practices and healing (What are some tools or practices you use?). As a final question, participants were invited to offer feedback on what questions might be missing when discussing wellbeing (What’s one question you think we should’ve asked about wellbeing, or that you yourself have?). The interview protocol was also translated to Spanish, so that participants can have the choice to listen to or respond to questions in the language of their choice (though limited to English/Spanish).

5.3. Participant Overview

Participants were recruited through personal contacts and connections in the three sites where research team members resided: Colorado, New Jersey and Washington. Across these sites, 19 young adults were interviewed virtually using variations of the collectively developed protocol. Participants identified as women, men and non-binary, and ranged in age from 19 to 24. Most of our participants were either currently enrolled or had completed at least one higher education degree, and almost all were either first- or second-generation immigrants. The following sections will detail the data collection processes.

5.4. Data Collection Overview

5.4.1. Data Collection in Region 1, Colorado: Paired Interview

Two participants were interviewed together over a Zoom call. They identify as 22 and 23 year old, first-generation Mexican Americans. They also shared that they did not attend university. Israel asked participants to write down their thoughts throughout the interview with the goal of hopefully creating their own wellness song. The session ran for about 45 min.

5.4.2. Data Collection in Region 2, New Jersey: Paint and Speaks

Interview sessions were structured around a “Paint and Sip” activity, each lasting 1.5 to 2.5 h. In that time, participants responded to questions from the collectively developed protocol, with some modifications, painted, and took breaks in between. Ten participants were divided into seven sessions, leading to a mix of five individual and two group sessions (one group of three and a paired interview) over two months.

Although all regions agreed to use the same protocol, there was some flexibility to curate introductions and conclusions when talking to folks. The participants were made aware of the nature of the interviews beforehand; the initial point of contact and the following consent agreement was explicit about participants agreeing to painting while answering the questions. The same clarifying note was added to the protocol so as to remind participants that painting was allowed during the interview, if not extremely encouraged. We sent participants a “wellness box”. Each box had a paint set, a small canvas, an apron, a towel, and a small bag of treats, hand sanitizer, Play-Doh and relaxing tea.

5.4.3. Data Collection in Region 3: Washington

Alexia, the site lead in Washington state, interviewed four women and two men, all in their early to mid twenties, in pairs. These three paired interviews were conducted virtually using the Zoom platform and were anywhere from 45 min to one hour. Unlike the other sites, Alexia conducted one paired interview in Spanish; they preferred discussing wellbeing in their native tongue. At the end of the session, Alexia shared links to relevant mental health resources to all her participants and also followed up via email.

5.5. Young Adult Reflections on Data Collection Process

5.5.1. Reflection by Israel

My process was team-led but also very individually uplifting. Being an artist, I decided that no matter what way I went, I would take a creative approach. We decided to go with interviews instead of surveys because we wanted to collect real conversations—which is still collecting data. Anyone can answer questions on a survey, but asking the survey questions and getting to know who is filling out our survey is more impactful in my eyes. We decided to tackle mental health as one of the areas of focus because you can look at the world today and some people do not want to be here on this earth. A lot of this stems from mental health. It can be similar to cousins we do not like or a pimple we are trying to hide, but mental health does not discriminate. It affects a lot of the Latine community, especially when we are taught from a young age not to talk about our issues and to hold what we feel inside. Mental is what should be pushed over the mountain to help our new leaders grow personally and in community.

- I’ve been thinking of my mental health to find some joy before my mental melt…

I wrote this lyric in a song about mental health, at the end of phase one of the project. What it means is that I want to be happy and find peace because I am one mental health episode away from losing my life. I talk about this with the line about my mental melting, which I see as slowly dying to the heat of the world.

- Other lyrics from the song:

- What is wellbeing when you

- by your self

- I was the oldest out my momma house

- Comiendo frijoles and government lies

- My binsta has been drifted

I break these lyrics down like this: when you are dealing with mental health, you feel lonely and closed out from the world. Where even self-care feels depressing because you shut the whole world out. It stems from growing up in a Mexican

Section 8 home where beans for most people sounds like a cool taco night; for me, it was fed on a plastic spoon by the government; for them, I was just another bean in the pot. The environment I was raised in was a reflection of that. I worked a job at 13 to help because I was the oldest in a family of three new to the U.S.

Music is key to mental health and wellness. From an early age, sound is a very important part of our lives, from hearing my mom’s loud Mexican music, our cousins playing old school R&B, and my uncle’s rap music playing in his beat-down car. Music is part of our wellness story; it is what shapes our world. One song can take us to happy or sad places. For better or worse, all I know is that music saved my life and gave me purpose. I know a lot of other people who could relate or feel the same way, even branch away from our mom’s music. We find our community of music to the point where every moment is a sound track. Even with depression on the rise and anxiety reaching all time highs, music is what our young people lean on for an escape. It is like when the music is playing nothing else matters; so, with that information, I believe everyone should have a wellness song.

5.5.2. Reflection by Des

I was inspired by a video I had seen on Instagram showing a Paint & Sip session. Everyone was singing along, drinking, and painting in community. There was this sense of unity despite the possibility that most participants were not familiar with each other. Being moved by the energy created in that video, I believed that having youth paint while answering difficult questions could also be an enjoyable and comforting experience. Thus, in addition to creating a dedicated space for thinking about wellness, we can ease into these topics and ideas through a “childlike” activity, opening up our minds and letting participants create a familiar environment before talking.

We wanted our participants to feel comfortable and safe while answering our questions; so, we provided folks with items that would keep their hands busy and mind from wandering as we sat for more than 60 min. Again, we wanted to emphasize the inherent joy that comes from engaging in arts-based activities, giving us the mental capacity to think about our most personal experiences while recreating our happiest moments.

Given my understanding of how uncomfortable and lonely Zoom calls can be, especially interviews, I wanted to incorporate an activity that would soothe folks who felt uneasy about appearing with their camera (especially with strangers). I thought about the things that help me relax while stressed and I landed on painting. Doing something with my hands that feels satisfying to do and is colorful gives me joy. I thought it would be the perfect way to invite folks to be open about their wellbeing without making the process seem too solitary.

Art also allows folks to express their ideas in ways that are verbally indescribable, especially with such an abstract and complex idea like having to describe one’s wellbeing. And better yet, folks were given something to take back with them. We reminded folks that their paintings and supplies were theirs to keep and reuse; this was intentionally carried out to build a reciprocal relationship between interviewer and interviewee, unlike other methods that might feel extractive and/or exploitative to a vulnerable young person. We did not want the conversation to feel rushed or forced, and we believed that having at least 1.5 h to paint and talk would give us sufficient data regarding Latine youth’s current understanding of wellbeing and healing.

5.6. Data Analysis

Interview transcriptions followed a two-step process. The first was using a talk-to-text program within the Zoom platform that recorded the session. Research team members then reviewed these transcripts while listening to the audio, to revise any inaccuracies and construct a more coherent final transcript. Interviews conducted in Spanish were transcribed but not translated; instead, they were analyzed in their original language. As is common in qualitative data analysis, the research team used an iterative process to read through the transcripts and develop a set of codes with memos grounded in the data. Part of our iterative process involved a first review of three transcripts, where we each identified excerpts that stood out to or resonated with us, and noted any questions or thoughts we had. We discussed these excerpts and processed the feelings they may have elicited. After this, we carried out a closer read of a subset of transcripts and created an initial list of codes that emerged. We compared lists, condensed similar ideas, and combined others to create a codebook with 52 parent codes with an additional 35 child codes and input these into Dedoose. Dedoose is a cloud-based qualitative data analysis software program we used to code each transcript using the set we co-developed.

Finally, we collectively refined and organized our codes to formulate a set of themes, which are reported in the following section.

6. Findings

In this section, we focus on six themes that emerged from the data: Sad Boi Vibes, Familia, All About the Pesos, Convivencia, Rootedness and Movement, and Healing and Joy. In each section, we engage with the data by offering images, participant quotes, and song lyrics and/as analysis. All participant names used are pseudonyms.

6.1. “Sad Boi Vibes”

Our participants repeatedly expressed that they experience prolonged periods of sadness and exhaustion. Although not all are clinically diagnosed with depression, our young Latines associate their constant state of exhaustion with stress and anxiety. We felt that the most appropriate way to capture the state of their mental health was to use the term “sad boi vibes”, rather than “depression” or other more clinical terms. The term “sad boi vibes” is a popular internet meme/saying mostly used by young teenage boys who have recently suffered from heartbreak. Common visualizations of the meme include teenagers in a dimly lit bedroom, listening to music on their bed, and covered in blankets. Although the term “sad boi vibes” can have a despairing meaning, it is frequently cited in humorous social media posts and is intended to form a connection between the viewer and the digital content. The meme is supposed to make young people feel less alone, remind them that others are also going through similar situations, and that humor can be used to lessen the severity of woeful feelings.

We want to honor our participants’ experiences through the ways that young people popularly express themselves online. We also want to highlight young peoples’ incredible ability to transform a chronic, debilitating sadness into something that is humorous and human. It is our way of giving back to our participants and the greater community by emphasizing the validity of our creative expression and outlet, even if it does not sound “professional”. We believe that the term “sad boi vibes” is a firm representation of how young Latines describe and manage aspects of their mental health.

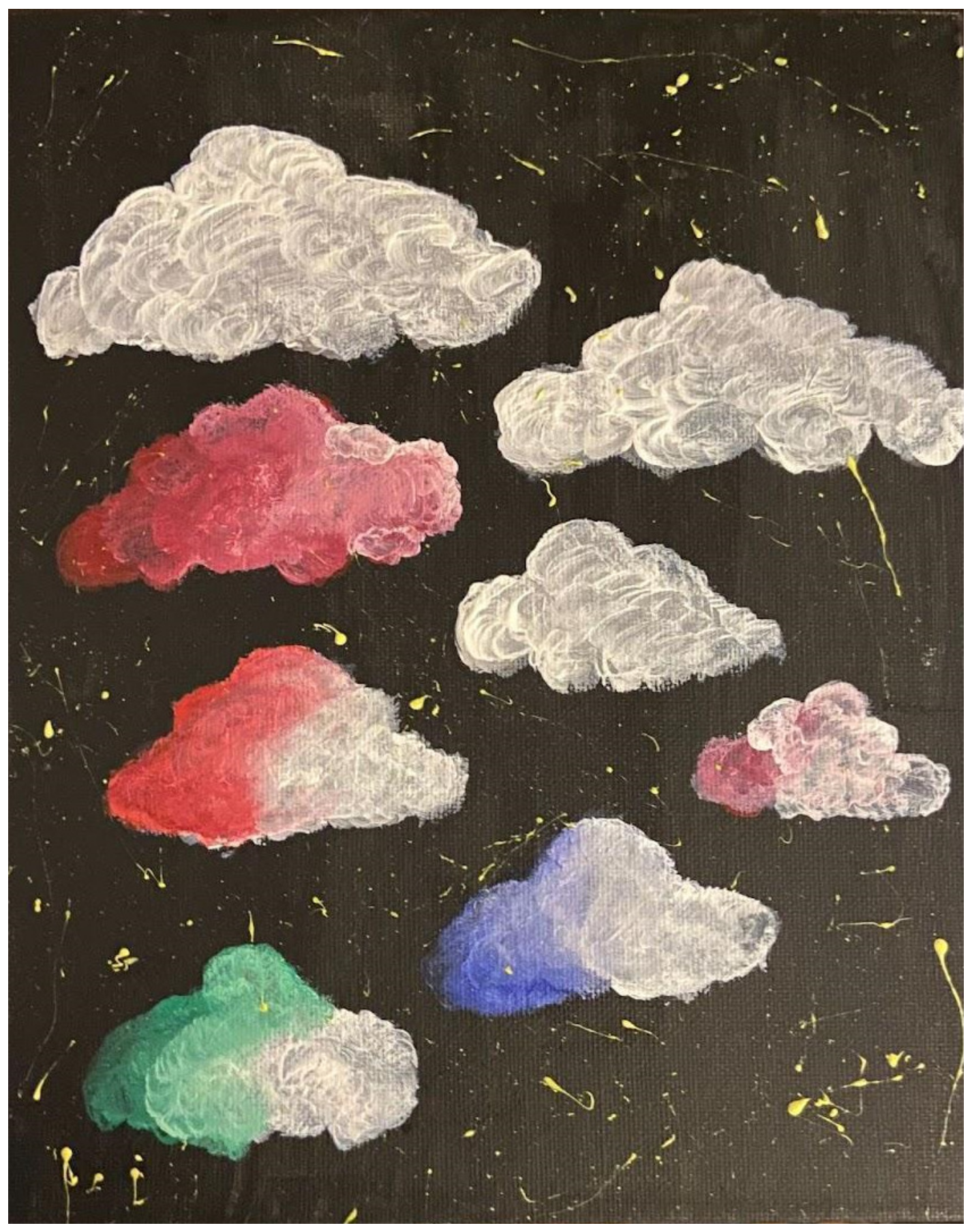

One of the pillars of “Sad Boi Vibes” is depression itself. Many of our participants spoke about their daily struggles with perpetual exhaustion: “Like just exhaustion you know what I mean when you can’t get out of bed and you’re just so tired and you just feel like sitting in the dark”. And these feelings of weariness can ultimately accumulate when not addressed early, like one participant, Melanie, said in describing what they painted (see

Figure 1): “…when your mind’s cluttered is just like this or when you’re sad. A lot of the colors that are relevant to those emotions it’s like really dark colors or just feeling like down in the dumps…”

Young Latines are struggling. They are suffering. Unlike past generations, today’s Latine youth are not afraid to acknowledge that they feel “off” and that always feeling tired or being unable to take care of themselves is not a sign of inept “laziness”. It is actually the manifestation of unresolved and deeply complex emotional needs that the young person is forced to mask in order to survive their day to day.

According to our participants, the need to manage an insurmountable amount of stress leads them into a cycle of perpetual ill-being, as two participants described:

“Another part it’s like almost this panicky feeling of like this pressure I feel like.”

“I’m just overthinking and stressing about what’s going to happen next, or a lot of stuff.”

The concept of stress is not new but its impact can vary depending on the youth’s race/ethnicity and background. For example, a young Latine in high school who must financially support their family is burdened with another layer of stress a White, middle class high schooler usually would not have to consider. In fact, our participants were very transparent with their inability to quickly “bounce back”. Some of our participants revealed they have trouble with time management and/or lack of energy. These are common indicators of depression and are reflective of the body’s continual fight to expend as little energy as possible. These feelings of weariness are constant: they are what’s left of a young Latine person who has tried not to deplete their limited energy too early. These same conditions were also placed on our elders, parents, grandparents and their ancestors alike, who also experienced that burnout and these same negative health outcomes. The sadness and exhaustion is carried on, almost synonymous to carrying on our culture and language. Does perpetual tiredness make us who we are as young Latine people? Like one participant said, “…when you’re like first waking up in the morning and you’re not excited for the day but more so, like oh here goes another day.”

Until it ultimately reaches a climax:

“I’ve had several times where I’m just like stressed and stressed for like a good week but there’s a point where, in my brain it just crashes and you’re just like all right, like I need to do something else, where it is something that needs to change.”

Feelings of emotional overwhelm can easily trigger states like the one mentioned above. Our youth are led to believe that they only have themselves to rely on. Young Latine youth might feel isolated from their family members or their friends. They could blame themselves for their misgivings and fight against their body’s urgent need for rest because of the expectations set on them. We can see why our participants had a hard time defining wellbeing when they were first prompted during our interviews. If you are constantly worried about your next task, when do you have time to think about yourself? Asking young Latine adults to define their wellbeing and how they can achieve it helped us unlock an understanding of the state of mental health amongst young Latines in the U.S., and that feelings of helplessness and disillusion can ultimately cause them to burn out and lose their grounding. Offering young Latines a chance to sit down and meditate on their innate understanding of themselves and their mental wellbeing is the first step in securing better emotional health across young Latine people.

6.2. All about the Pesos

Financially Free

- Creativity im rich financial Im struggling

- Trying make a dollar off 99 cents

- I got one second left

- As take my last breath

- Im fulled of music and long term successes…

- I’m 3 generation of broke

- But first generation of woke

- I walk across mountains and jump

- over valleys

- My goals is write songs and shine Grammys

— Poem by Israel

“It’s like capitalism, you know work work work…and then those people that are like grind time prime time like makes me want to throw up like for the longest time I thought, if I wasn’t hustling I wasn’t doing it right”. Quote from Melanie

Hustling. The Grind. Being Young. Why are they so tied together and how does this impact our Latine youth and young adults? When we asked our participants to identify if they could afford health-related services like insurance, healthy food and other medical needs, most of them answered no. For those who are in higher education, they feel the need to constantly work in order to offset the high costs of university tuition, books, and other materials needed as a student. Some of our participants told us that they need to work while still excelling academically and caring for their siblings as a promise to their parents and families. These expectations and external and internal pressures to succeed in all areas of life can lead to a tired and weary young person, all for the sake of obtaining a livable income.

For instance, in the quote above, the participant noted that because of the capitalist system in which they find themselves, they have to work to afford basic needs, especially as a student who finds it shameful to ask their parents for additional income when they are busy supporting their families and household. Many of our participants highlighted that their parents are immigrants who yearn for a better future for their children. The concept of the “American Dream” has misled older Latine parents and individuals into believing in the “pick yourself up by the bootstraps” theory of success in the United States, and (un)knowingly have subjected their children to the same flawed theory. Knowing that their parents sacrificed everything for their children’s futures, leaving behind their families and homeland ties possibly forever, can place a heavy burden on a youth’s shoulders. Since young Latine adults are expected to have the “privilege” of young age and ability, presumably no children (not in all circumstances) and no ties to property, what else should youth be doing but making money?

“If I need something, like I really like, hustle like…Hustle hustle hustle. Like, anything I need. And I feel like that I also do it because I don’t if [my mom’s] done already so much for me and I don’t want to like [have] her to have to worry about me.”

There is a lot of pressure for a young Latine adult to succeed in this country. Sometimes, that pressure can come from educators or leaders that insist that good grades, dedication and willingness to achieve something can get you everywhere in life. Other times, that pressure can come from their family members. They can place an unattainable expectation on them to achieve an ultra-wealthy lifestyle, have them take care of their elders when they’re older and look after their siblings. And as youth, sometimes they are consumed by the idea of always having to work for something. They are led to believe that nothing good can ever be free and if there was no sacrifice there can never be a reward.

“I feel like people don’t realize, yes, we have things that we want in life, but in order to get where we want in life, we have to work twice as hard just because the world that we live in, refuses to pay what we deserve to be paid.”

As such, young Latines are overworking themselves to meet their parent’s vicarious desire of personal wealth and independence or to meet the needs of the American capitalist economy, not to mention that youth must also provide for themselves and prioritize their own personal goals. Are young Latines not allowed to rest? Do they not deserve rest? Or, can they simply not afford it?

Like Denise expresses in her painting, (see

Figure 2),

“It costs money to be born for people that don’t have insurance. Those hospital bills, they cost money to be born and when you die it costs people more to die! Like that’s it there’s no ending.”

Even young Latine adults who are lucky enough to be in tune with their health needs face very real structural obstacles in healthcare. If the stigmatization of mental health and Western healing practices (psychotherapy and psychiatry, for example) in Latine families were not enough (more on this in the Familia section), young people who acknowledge that they need professional help and are ready to seek therapy cannot do so because of high costs. As Latine youth ourselves, we empathize with our interviewees because we know how difficult it can be to attain well-deserved, culturally relevant and compassionate care: it’s too expensive, the therapist’s office is too far, and not to mention… it’s too White! These structural barriers are preventing young Latine people from achieving the healing they deserve; its effects can eventually snowball to the point where they feel too exhausted to listen to their body’s needs.

The need for money and wealth in this country is destructive and its impact on Latine young adults can be seen through their desperate call for more affordable healthcare, higher wages, visibility and empathy from their elders and policy makers. They face pressure from family members, educators, the ultra-wealthy and elite, and are left to face the sinister ideology of the “American Dream” and not to mention the pressure they put on themselves. The need to “grind” and “hustle” is tiring them out. It’s tiring us out. Do we not deserve to be young?

6.3. Familia

Families can be a source of positivity and joy for young people, especially Latine young adults. Some of our participants shared that they feel their best when talking to their parents about their issues or struggles. They also shared that they feel heard and cared for by their parents. Even with the most delicate of issues, some of our young Latine adults revealed that their parents are a source of consolation.

“It’s funny like we how we still like all like hang out and stuff like here and like work with like my parents like if we go to a store really yeah let’s go together or if we go if we do go to a family event it’s all of us like we’re always a big family.”

On the other hand, there were some participants who shared that they did not feel safe talking to their parents about their mental health struggles. They spoke about how some Latine parents refuse to acknowledge their child’s sadness or anxiety; some even minimize these feelings as symptoms of laziness. Instead, some of our young people looked to their siblings, other close friends and younger family members for the kind of nurture they were seeking from their parents (see

Figure 3, Elena’s depiction of her goth sisters).

“My sisters of course they’re like my support. I love them like so much and we share, like so many experiences together and they know everything about me. I know, I think I know, everything about them and we just share so much time together.”

However, considering that many young people live with a parent or elder, it can be difficult to access these nurturing avenues. This kind of household can lead to a strained parent–child relationship in which a child feels unheard. We saw that many older Latines responded with similar advice: “you should be so lucky” and “stop being lazy.”

“Me sentía triste y deprimida estos últimos días y se lo dije a mi mama y lo único que me dijo: ‘deja de andar con tus dramas, ponte a limpiar tu cuarto’ y hace el comentario like, girl, yo solo nomas queria que me dijera, “oh you need to talk about it?” “Que sientes?” Eso, pero no, a las mamas le dices “me siento deprimida” [y responden] “andas de floja, andas toda ahi nomas con tus dramas”. Translation: I felt sad and depressed these last few days and I told my mom and the only thing she said: “Stop messing around with your dramas, start cleaning your room” and make the comment like, girl, I just wanted her to tell me “oh you need to Talk about it? What do you feel?” That, but no, to the moms you tell them “I feel depressed” [and they respond with] “you are lazy, you are all there just with your dramas.”

Our participants have a shared understanding that their parents did not have the tools necessary to cope with their own struggles as children and young adults, and sadly this inability to understand their emotions seeps into parenthood. Our participants noted that it can be difficult to soothe themselves when they find that their parents also need soothing, and that many of the difficulties that their parents faced with their own parents continue into the next generation. As young Latine adults in this period of time and in this country, our participants are (forced to be) more in tune with themselves and their mental health needs, and despite the validity of their feelings and experiences, their parents have a lifetime of emotional scars that were left untreated. This can lead young Latine people to second guess the legitimacy of their own struggles, often comparing the severity of what they are going through to the traumas of their parents. Young Latine adults begin to think of their mental health issues as juvenile tantrums and not debilitating mental health issues because our parents or Latine elders have ingrained in them the concept of true struggle. Latine youth are left feeling guilty.

This aspect of familia is deeply connected with the expectations placed on a young Latine by their elders. According to our participants, young Latine adults have trouble talking to their parents about sensitive topics, especially when concerning issues that the youth identified as being perpetrated by the parent. As Latine youth ourselves, we recognize our need to fulfill the desires of our parents and live up to what they wish us to be; knowing that despite the harm caused, their intentions are wholehearted. We are left to reckon with knowing that our deepest desires would go against what our parents dreamed and prayed for us. As such, it is only just that we associate these feelings of guilt to the concept of intergenerational trauma. Our parents probably faced similar mixed emotions with the way our grandparents envisioned their futures; if they were not able to meet their parents’ expectations, that guilt, pressure and shame is sadly “passed down” to the next generation.

“I literally needed to like call my mom so she can give me that extra push she, she literally like call me because I was texting her, I was like should I go like I’m not sure she was like call me and then I call and she’s like leave! Like go home and go to sleep!”

“There’s a lot of shame and guilt that goes along with not following the path that your family wants you to take.”

Our participants highlighted the gendered family structure that remains pervasive in their community. For example, some of our participants shared that as the eldest daughter of the family, there are certain duties and responsibilities that are placed on them and not their other siblings, even if they have older brothers. Although this account falls under the “Machismo and other isms” theme (something that is not directly discussed in this paper but was a theme), we cannot deny the burden that women in a Latine family carry on their shoulders. This adds another form of generational trauma and set of expectations to a young Latine. What will it take to stop the perpetuation of what our colonizers did to our ancestors? Why does the hurt continue and live on for centuries?

6.4. Convivencia

As the research team analyzed interview transcripts, the theme of community emerged in a way that was difficult to define in English. One team member, Alexia, suggested that what people were describing was actually convivencia.

Convivir, directly translated, means to “live together”, but it is also more than just sharing a physical space. Convivencia encompasses a depth of knowing the other and a sense of togetherness. It is sharing life with one another [

2,

23]. Throughout our interviews, convivencia was deeply present. Many individuals talked about the importance of belonging, friendships, family and how their wellbeing was positively impacted by feeling seen, known and connected to others. As one participant shared, “somehow talking to people makes me feel happier, and like, more energized, like, I’m getting closer to, like, forming these deeper connections”. Some noted that this idea of convivencia, of being there for one another, is a cultural feature of their experiences as Latines. As one young adult explained,

“At least with my personal experience, everyone’s kind of there for each other in one way or another, so it’s a comforting Community for the most part. There are some instances where, you know its competitiveness, so you don’t want to associate but, for the most part it’s a more welcoming Community.”

With the caveats that this reflected their own experience, and cautions of “for the most part”, this participant described community members in support of one another, being present, and being part of a comforting and welcoming community. Critical to wellbeing is this feeling of welcome and support, though convivencia does not mean a lack of all conflict. The participant also acknowledges that convivencia can suggest a sense of being present despite the tensions, especially tensions that result from competing with others for limited resources. Convivencia is expressed as a deserved reality and invokes a deep desire for it when it is not present. Several participants talked about this as having a need for safe spaces as a public good and not just a private obligation. For some, home and familia serve this need but home is not always safe, as explained previously, and having a place to go for this kind of connection is important:

“Encourage like having safe places whether that’s at home or in some other space, you know, it doesn’t matter it’s just encouraging that because a lot people don’t feel good at home, so they go somewhere else, [whereas] a lot of [other] people feel good at home so that’s why they don’t go anywhere else for that. So I feel like there should be, like sections for people when like encouraging “hey it’s okay to open up” and “it’s okay.”

This young person envisioned spaces where people can go to “open up” in a safe environment with others. Not necessarily in a medically therapeutic context, but in a community healing sense—as a sanctuary space [

14].

For some, these deeper connections of convivencia were formed through the bonding experiences of community organizing and other solidarity work. More than one participant indicated that they are committed to giving back to their community and frame this work as one facet of convivencia and collective wellbeing. One participant pair discussed how the work they carried out as part of a Latine-community-based organization was meaningful in terms of affecting change in the community, but also for the wellbeing of those engaged in the work:

“Like working with [CBO name] before and doing stuff like that, has also helped me because that feeling that it feels so good…”

“[the work] really impacted me in a way, in a positive way, because I was like I, I want to help out my community.”

It is important to highlight this aspect as it underscores the need to understand wellbeing, not just from an individualistic, self-care standpoint, but a collective one [

2,

11]. And this collective or community wellbeing can be action-oriented, through movement work, community education efforts, or expressing solidarity with others through emotional and material support [

24,

25]. One young adult explained the importance of more material supports and mutual aid as a concrete form of solidarity:

“I just think like we definitely need to like get just… straight up support one another, that support like… yes you’ll see it over instagram like oh support this support that but it’s like where’s that support in reality? Like put your money in where your mouth is. You can put it all over social media as much as you want, but are you actually there in the present?”

Particularly during the pandemic, mutual aid arose as a more material way of expressing solidarity with one another as government support failed them [

26,

27]. Again, this idea of people coming together as a collective was seen as something critical to their individual and community wellbeing. For young people to thrive, certain conditions need to be met which can only be brought about through structural change. And it is through collective efforts, even if incremental, that these changes can happen:

“I feel like the only way that’s going to happen is that if we just collectively wake up and say enough is enough. But I feel like that’s happening; that’s happening, little by little. So it’s like, hope is there.”

In this quote, the participant asserts her belief in collective efforts to effectuate change. This entails developing a critical consciousness around the systemic inequalities that permeate their lives and collectively moving towards changing these conditions. She is deciding, in her words, that “enough is enough”, though frustrated with how slow this change is to come. Despite all of this, the participant expresses hope that change will happen by observing and being part of those moments where it is apparent. Hope/

esperanza is often a strand of healing. Not as an empty optimism, but a working hope grounded in the critique of social structures and cushioned by convivencia [

14].

6.5. Rootedness and Movement

“Trees also represent family, you know your roots. And the age when you cut you know, a tree and you look at it, you know little circles and you see how old it is and how much shit it’s gone through and still here and stuff like that right, and you know. How it’s lasted all these decades and it’ll grow around things and stuff like that that it probably shouldn’t be going around but no matter what it’s still growing.”

— Quote from Sandra

In the interviews, the interplay of rootedness and freedom of movement emerged as a theme. Many Latines are part of transnational families, and as such, we consider what wellbeing looks like in these in-between spaces. We use the term rootedness to describe a sense of cultural connection, historical memory and belonging. Connection to a sense of home and place is an important dimension to wellbeing; they are the soils from which community is forged and nourished. As Sandra beautifully describes in the above quote and image (see

Figure 4) using tree system imagery, knowing your roots gives a person a sense of place, history and social embeddedness. The rings in a tree, she further notes, represent the passage of time, of presence, survival and growth despite oppressive conditions—capturing the indigenous concept of survivance as the “active sense of presence over absence, deraciation and oblivion” [

28].

This resonates with other participants who spoke of cultural rootedness in connection with family and its importance to their sense of identity. It is often in the absence of this rootedness that its significance is most felt. Some spoke of the impact it had, as a sense of spirit loss to have these parts of themselves, whether it was in traditions, language, or ways of being, be suppressed or denied. As one participant lamented,

“… the pueblo that my parents came from, there was an indigenous language but at some point, they just stopped like teaching it to, like my parents never learned it and that makes me sad.”

This cultural erasure, stemming from colonial and White supremacist logics, is one factor that dampens individual and community wellbeing [

29]. It serves to detach a people from the wealth of their knowledge, to force them to conform to subordination within a racial capitalist system. For some, regaining a sense of rootedness meant traveling to the lands of their ancestors and reconnecting with these lost parts of themselves. As one participant explained,

“[Going to Mexico one year] really made me feel connected to like my culture and to my like where my parents grew up. And now I embrace it and I love, like I love being like Latina and even though there are obviously, like, obstacles we have to go through, like I still like where I come from.”

We see those in authority loudly proclaim how countries in Latin America and Africa are undesirable places whose people are threatening and suspect, and use these discourses to justify oppressive and inhumane policies. Pushing these narratives not only has clear material implications, but also mental health ones that push people to disassociate or deny their roots or feel shame. In the quote above, Elena’s trip to Mexico served to counter these narratives and better connect to her origins whilst prioritizing care for self. As she states, “now I embrace it and love it”, suggesting that she had not before. In these ways, rootedness can be tied to place (though not just a single one) and movement.

The freedom to move is another condition of wellbeing expressed by many Latine participants. In transnational families, the freedom to move between places is important to maintain familial and community ties. And for many youth and families, it is critical to survival. Global economic, political, and climate factors push, and some argue, force migration as wealthier nations strengthen their power on the backs of the rest. As conditions in their home nations deteriorate, people move to find better conditions for themselves and their families. Powerful nations like the United States have been impeding this freedom of movement at different points in history; currently, U.S. immigration and asylum policies have been more steeply eroded since the previous administration and our current one has been falling well short of its campaign promises. Immigration status and pressures, thus, become factors impacting youth wellness [

14,

29,

30,

31]. As one young person describes,

“Once I figured out like no I’m not a citizen, I was just like okay well it’s not a big deal I’m still here I’m going to school like it’s not like the police are chasing us so like we didn’t do anything wrong we’re fine. So once the whole DACA thing came into play and I actually had to like you know talk to the lawyer and, like, go through the whole proceeding I realized like wow I’m not okay like I literally could have been deported at any point.”

In this interview, Rose describes the moment when she grasped what it meant to be an undocumented immigrant. After meeting with an attorney to obtain the temporary protections initially offered by the 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the realization that she could have been deported left her feeling shaken: “wow, I am not okay”. Moving through the U.S. as an undocumented young person means there are many moments like this, realizations that their place here, their home, is precarious. This uncertainty is one that sits in their minds and bodies, sometimes as an uncomfortable background noise, and other times a wailing siren, permeating every thought and breath [

30,

31].

Despite all this, young people find strength and healing amidst these uncertainties and traumatic separations. Another participant describes:

“…My dad got deported like, I think like, 10 years ago, 11 years ago. So then, after that that was like a big big thing because you know now my mom was a single mom she had to make up for his income and like you know rent was not going to stop, stop coming just because my dad wasn’t here. So I feel like that really, like, motivates me now since I saw her, she never once like you know, gave up, you know she’s always been so independent and, like, showed me to be, like, really strong.”

In this narrative, we see how the respondent describes the impact of her father’s deportation in her life. In addition to the emotional trauma of the separation, there was an economic one, as her mother had to take sole responsibility of financially providing for the family and in terms of caregiving. Later in the interview, the participant explains how responsibilities at home were also shared with her as she had more linguistic, cultural, and eventually economic access to U.S. society in comparison to her mother (though not her U.S.-born peers). Holding up her spirits, what “motivates her” was observing her mother’s strength and what Cuadraz and Pierce [

32] have termed endurance labor; watching her mother not “give up” though the circumstances were crushing.

6.6. Healing and Joy

- On days where I wanna quit I remember I’m blessed

- I remember to breathe, I remember to rest

- I went to therapy to help with my mommas stress

- Like I’ve been thinking of my mental health …

— lyrics by Israel

“A lot of people say this and it’s probably a stereotype … but it’s like we we’re all so loud we’re also full of life, we were all so happy to be surrounded about each other.”

— Quote from Melanie

At the end of our interviews, we created a space for participants to ask us questions or share their recommendations about wellbeing. Most participants wished we had asked more about our joy and our hope. While young Latine adults described navigating multiple pressures, there were specific mentions of them working towards healing and finding joy in their lives.

There were conversations about all the different ways they find healing, whether through music and the arts or everyday actions like smiling to strangers or taking a walk in nature. And as the opening quote illustrates, some even found healing in reminding themselves that they are a loud people and full of life and connection.

Young Latine adults are at a point in their adulthood where they acknowledge that they are hurting and are working to heal intergenerational traumas. As they narrated the ways in which the pain of exclusions based on race/phenotype, gender, immigration status, language/accent, socioeconomic status and sexuality from outside and within their communities, they shared places of comfort and joy. Music and the arts was one such source for young people:

“…[I] just found comfort in my music, I found songs that could perfectly explain how I’m feeling…There’s like certain songs that I would listen to, where it explains how I feel and I’m not being judged on my emotions…So if anybody ever asks, what’s wrong with me and I send them the song they’ll just be like why? I’m like this is why. This is how I feel.”

Another young woman explained how music helps her process emotions like anger and sadness:

“Music affects my mood in ways it’s kind of scary but…Nobody asked but Hamilton is what I listened to, whenever I feel a certain type of way, and when I had that realization because I would find myself like going to that to that album like when I’m mad, when I was sad, when I wanted to do some damage.”

When spaces where young people can process and express emotions are unavailable, limited or discouraged, they create their own. With beats, rhythms and lyrics expressed in song, they can connect to others and themselves in ways that feel less scrutinized.

This feeling of being under constant scrutiny or surveillance was a pressure, an anxiety, from which young people sought healing. Where music was one popular medium, creating visual arts or crafts was another. A young adult Latina participant explained how crafting represented a judgment free-space for her, one that helped build confidence and hope during stressful times:

“…there’s no like repercussion if you fuck up a craft. You just get to do it. And you just chill and then not only that, but when you’re going through it, and life fucking sucks, all you need is like a little win and when you finish that fucking craft that’s like a little win. You finish it and you just feel like you’ve … accomplished something…it can help push you to get other wins, in my mind, because every time I complete something that I’ve started as a craft I’m like, ‘shit this feels amazing,’ like, ‘look at me.’”

Whereas the arts represented one healing tool, others spoke about being aware and present in their minds, bodies and spirits. Being able to see themselves on the other side of the harms and pains they experienced over time:

“I think for me healing means being able to look at myself and not see the things that used to hurt me anymore, and I could actually see myself again.”

There was a deep desire, for moments, even if they are few, where they can allow themselves to experience the sensations of joy and fulfillment, and a sense of belonging with others and the earth. A desire to be able to really thrive, rather than feel an absence of hurt. One participant explained that, for her, wellbeing and healing were evident:

“when you take in that deep breath and you’re not taking a deep breath because you’re stressed, or because you need to, you’re taking a deep breath because you’re finally where you’re sitting in a spot where you finally feel like you’re where you belong.”

The relationship between a sense of belonging, connection with others and nature came up in several interviews. As one person put it “I just enjoy nature, it gives me peace”. Variations of this sentiment came up frequently during the interviews and in the images participants created. In one of the paired interviews, the young men discussed the healing they experienced both being in nature and in community with others.

“We went to this trip my sophomore year into Utah, the canyons and, like the last day they had a campfire and it was weird because it was me and my friends. We actually like ended up all like crying and it was weird because, like we kind of talked about already like emotions and just like thoughts that were on our head. Like yeah. And it was like the whole camping trip for a week and for the last day to be like full of that and your friends and like just knowing it’s an area that like kind of way from my home and stuff and I just [being] around each other, like it free in a way. It was pretty cool because it was like we were the only ones crying. And it was funny because, like we were just thinking like dang we look so funny to like all the like white kids and things like that.”

This camping trip represented a time and space away from their daily pressures, a freedom to just experience their emotions with others and the land they were sitting on. The young men released the tensions and frustrations they carried, and shared these vulnerable moments with humored discomfort—as they added “dang we look so funny”—since healing spaces can often be denied or stigmatized particularly for Latinos and other young men of color.

Though nature and land were described as spaces where young people felt peace, not everyone felt like they had access to such spaces. Others felt the act of healing, or achieving wellbeing, was an ideal to strive for, but not necessarily reach. Rather than an abstract sense of fulfillment, it was seen by some as the freedom to not have to worry about survival: “Yo creo que bienestar es cuando llegas a un punto en la vida cuando no te tienes que preocupar económicamente para sobrevivir dia a dia”. The precarity of their circumstances sometimes left young people uncertain about whether healing was a possibility for them, as one young woman expressed: “I really don’t know what it is like to heal, and like, sometimes I think like, will it ever happen?” Yet, there was a sense of hope, if not for themselves, then for their younger siblings, and the generations that follow.

“I think that my life, healing would be [for] the future generations, and after me and stuff like that. And I might not get to be there to see it come true, you know, and my parents probably won’t get to be there to see it come true. [But] I hope one day that we get there, and that my generation’s just going to chill. You know they get to God, they get to chill with the world, they get to chill in their home and not have somebody remind them that there’s something about them that makes them different.”

7. Discussion

Using the emerging information from our interviews and collective group synthesis, we landed on the following definition for Latine bienestar:

“Wellbeing is existing freely, not just surviving. It is living in convivencia with a sense of peace and balance with ourselves, communities and nature.”

We want to capture the varying aspects of wellbeing in our definition so that we can better understand and act on what Latine youth in this country really need. Latine wellbeing demands that we exist freely by listening to our own needs and desires, as embedded within our communities. This freedom also calls for the end of “hustle culture” and of racial capitalism and its incessant demands on young people, especially young adult Latine who are expected to uphold the “American Dream” success narratives. Some scholars have talked about this as a dimension of economic wellbeing [

1,

3], and within the context of feeling financially secure for survivability and not necessarily great wealth [

5,

11]. We frame this as freedom from racial capitalism to highlight the structural nature of the issue rather than focus on how young Latine should learn to better navigate “the grind” to achieve wellbeing [

9,

11,

12].

In line with what researchers have found with Latine adults, wellbeing can center on convivencia, or sharing life together [

2,

23]. A term whose meaning is difficult to translate, Jasis and Ordóñez-Jasis [

23] offer the following description of convivencia: “the flowing moments of collective creation and solidarity, the bonding that developed from a joint, emerging moral quest against the backdrop of experiential sharing”. We are called to respect, love and cherish those around us, to build community, as we work on joint projects of liberation. To truly live in community also means being able to rely on each other and seek help without fearing judgment, shame or anxiety. One of the first embedded circles in which Latine youth practice convivencia is with our families. Like much of the literature on Latines, familia was an important factor in our participants’ wellbeing and sense of happiness [

2,

5,

6,

7]. Often, these were sources of strength and support, but like other scholars have found, young adult Latine also described how families can be sources of stress and worry. This stemmed from gendered expectations, the structural conditions and oppressive policies that put pressure on families, and guilt for expressing their own needs and desires amidst at times overwhelming obligations [

6,

8].

Expanding on the idea of convivencia in our definition of wellbeing, we also emphasize the importance of collective wellness and community care [

2,

4,

10,

11,

14]. Our participants shared their personal experiences with understanding their own wellbeing but they also highlighted the additional need for the community’s wellbeing. We find common ground with other scholars who have also argued for a community focus on wellbeing, with a view towards collective liberation [

4,

10,

11,

14]. This makes us ask ourselves: what about others in the Latine community who are not youth? The wellbeing of our elders so greatly impacts our own trajectory; as such, we hope to see our elders connect with our discussion on family dynamics amongst Latine families in the U.S. Our wellbeing is interlinked, and having more opportunities for intergenerational conversations and projects around wellbeing, with both elders and youth engaged and willing to be genuine about their feelings and experiences, is important for family wellbeing.

For this to happen, we also recognize that broader social changes are necessary, to create the conditions where these opportunities can flourish. As such, we want to provoke policymakers and other leaders to make the necessary policy changes that support financial stability and the freedom of movement. As noted in our analysis of rootedness and movement, it is very important that our Latine youth can see their family members and vice versa [

8,

33]. The ability to physically connect with our elders and our culture is critical to our wellbeing as young people [

5,

10,

12,

14]. Forcing us to be physically separated from our relatives can lead to feelings of erasure, disconnect and distress [

8,

15,

33].

In addition, we ask our adult allies to think about the types of support they are offering young Latine adults, especially our allies that work as mental health professionals and wellness or wellbeing practitioners. We join critical mental health scholars in asking professionals to consider the following: Is your work creatively and culturally grounded? Are you using healing-centered engagement? When speaking to Latine youth, are you situating their experiences within larger structural conditions and understandings of historical trauma? [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Having practitioners that are aware of the (young) Latine struggle in the U.S. can help us open up about what is on our mind without feeling ashamed, exploited or guilty. It can be difficult (or nearly impossible) to speak to an elder or a parent in our own households, so we want to make sure that our (Latine) mental health professionals are aware of the impact they can hold on young people. They can do this by hearing us and asking questions about our family dynamics, our understanding of healing and joy, how we feel about our rootedness and movement, being cognizant of the deathly implications of racial capitalism on Latine young adults.

Finally, we want policymakers and affiliate community organizations to continue to engage in public investment, especially in urban, industrial areas. This involves (re)investing in public spaces, our schools, libraries, community centers and parks. The Latine youth we interviewed discussed the spaces and practices they found to be healing, where they found joy, and these often involved cultural and creative productions like music, art making, and community work. The spaces where such creative healing engagements can be enacted, where youth can “embody their knowledge in an otherwise form”, [

34] are limited and under threat. Our Latine youth are demanding further care in our community spaces, to create more opportunities for what Goessling [

16] terms youthspaces, so that we have free and accessible areas to gather with friends and family and engage in creative, liberatory projects. This also includes expanding limited green spaces in urban areas and providing basic safety fixtures like lamp posts and designated walking areas. Our interviewees expressed their understanding of wellbeing through their depictions of public landscape, access to trees and the healing power of nature (see also [

35]). They revealed that being in tune with our physical environment provides us with the space to think about how we fit with our surroundings and allows us to breathe.

Already, the programs in schools, libraries and communities where such opportunities are offered, the arts and body activities, the teaching of anti-racism, our histories, cultures, and resistance stories, are being defunded, often on the basis of White supremacist logics of dangerous “woke” curricula [

36,

37]. Connecting with other youth, and mobilizing with our adult allies, we can creatively engage and interrupt these oppressive narratives and structures that benefit from our not being healthy [

18,

19,

24,

38].