Abstract

Violence in adolescent intimate relationships poses a real threat to adolescent well-being and is a risk factor for recurrent violent patterns in adult marital relationships. The present study aimed to understand the relationship between different dimensions of childhood trauma and dating violence perpetration and the mediating role of temperament. The sample was composed of 3497 adolescents (n = 1549 boys, n = 1948 girls; M = 1.56, SD = 0.497) aged between 10 and 22 years (M = 15.15, SD = 1.83). Instruments used in this study included the Social Desirability Scale, the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), and the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ). The results show that temperament plays a mediating role in the relationship between dating violence perpetration and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. Furthermore, the results suggest that adolescents who have been abused in childhood tend to demonstrate more temperamental problems and a greater susceptibility to the perpetration of teen dating violence, but only in the more severe dimensions of childhood trauma.

1. Introduction

Adolescent dating violence (ADV) constitutes a significant problem in our society, and it is being considered as a strong predictor of domestic violence given that violent behaviors that start in a dating relationship could continue in future marital relationships [1]. Factors associated with ADV include interactional patterns that increase the likelihood of conflict and the perpetration of violence [2]. In this line, research suggests a strong association between experiencing child maltreatment and later perpetration of aggressive behavior [3,4,5]. More clearly, other studies indicate a relationship between experienced child abuse and later partner perpetration [6,7]. These early traumatic experiences (e.g., neglect, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse) are a broad phenomenon that includes harm or potential harm or threat of harm to the child even if is not intentional. The most common behavioral problem among emotionally abused children is the externalization of behavior, such as aggressive and destructive behavior [4], due to a familial atmosphere of hostility and rejection [5,8].

Evidence in the literature appears to support the social learning theory and the intergenerational transmission of violence [9,10]. These theories explain that in environments of chronic or cyclical violence, family dynamics and caregiving can impact children’s functioning and their role in reproducing violence throughout the various stages of their lives [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Therefore, family conflict, harsh parenting, physical and psychological abuse, and neglect may worsen negative effects of exposure to community violence and contribute to processes that reproduce violence [13,17,19,20,21,22]. Additionally, several studies evidence that individual initial dating relationships likely provide a bridge between the attachment patterns established in childhood between individuals and their caregivers and the attachment styles that are expressed in future adult intimate relationships [23]. This is in line with Bowlby’s theory [24] about attachment styles. Insecure attachment dimensions have been associated with dating violence perpetration [25,26]. However, dating violence perpetration might occur differently depending on attachment style. For example, individuals high on avoidant attachment may use violence to maintain their psychological distance in the relationship, whereas individuals high on anxious attachment may perpetrate violence in response to their jealousy, emotional dysregulation, or fear of abandonment [25].

There is evidence of associations related to temperament and various psychological problems, such as behavioral disorders, difficulties in social skills, prosocial behavior, and anger or aggression [27]. Temperament consists of relatively consistent basic dispositions, inherent to the person, which shape and modulate the expression of activity, reactivity, emotionality, and sociability. The main elements of temperament are present early in life and are strongly influenced by biological factors [28]. On one hand, youths with conduct problems from childhood show temperamental characteristics that contribute to their deviant behavior [29], and some studies have examined how difficult temperament can contribute to the development of conduct problems. So far, two developmental pathways have been identified: problems with emotional regulation and problems with low emotional arousal [30,31,32]. On the other hand, there have been recent calls for the importance of examining both cognitive and emotional processes early in adolescence as potential mediators of family violence and ADV [33], as is the example of temperament. That contributes to a greater understanding of the processes mediating the intergenerational transmission of partner violence that could inform family violence theory and interventions designed to interrupt this cycle [34]. For example, a study by Reyes et al. [33] revealed a direct exposure to violence led to increased acceptance of ADV and anger dysregulation, which in turn led to an increased risk for ADV perpetration. Given these characteristics, it becomes pertinent to explore the role of temperament in maltreated children and the perpetration of violence in a dating relationship to have a better understanding and perspective of the reasoning behind the behavior. Analyzing this link can provide information for implementing timely and targeted prevention interventions.

In the light of the foregoing, this study aims to assess the association of childhood exposure to abuse and neglect with dating violence perpetration in a community sample and examine the moderating effect of temperament characteristics on the association between childhood exposure to abuse and neglect and adolescent dating violence perpetration. This is particularly important because, while recognizing the multidetermined nature of behavior problems, much research has focused on single causal factors. However, as Frick [35] indicates, a better understanding of the phenomenon involves considering the interaction of different factors for the development of behavior problems. Considering the proposed objective, the present study sought to investigate that temperament mediates the relationship between all dimensions of childhood trauma and dating violence perpetration (DVP), since it is associated with relatively consistent basic dispositions, present early in life, that can shape and modulate reactivity, emotionality, and sociability responses of the adolescent. Therefore, five hypotheses were defined, namely: (1) temperament mediates the relationship between emotional neglect; (2) temperament mediates the relationship between emotional abuse and DVP; (3) temperament mediates the relationship between physical abuse and DVP; (4) temperament mediates the relationship between physical neglect and DVP; (5) temperament mediates the relationship between sexual abuse and DVP.

2. Materials and Methods

Data were drawn from the Interpersonal Violence Prevention Program (PREVINTTM [36]). PREVINTTM is an original psychological intervention program designed to prevent the development and expression of aggression in adolescence. Previous to the intervention process, the sample integrated 3803 adolescents from 52 Portuguese public middle and high schools, in rural and urban areas, from various districts of the country, both mainland and islands. The final sample consisted of 3497 participants (n = 1549 boys, n = 1948 girls; M = 1.56, SD = 0.497), with ages between 10–22 years (M = 15.15, SD = 1.83). About 1291 adolescents self-reported no involvement in DVP (n = 571 boys, n = 720 girls), while 2206 adolescents (n = 978 boys, n = 1228 girls,) self-reported DVP.

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

To gather data related to the participants, a sociodemographic questionnaire was used. This instrument was composed of questions regarding sociodemographic questions, personal information (e.g., age, sex, and school grade), and family-related questions.

2.1.2. Social Desirability Scale

Social desirability scale (SDS [37]) is a self-report measure, with 20 items of dichotomous response (yes/no), validated for the age groups in this sample. Example items include “Have you ever hated someone?” and “Have you ever taken advantage of someone?”. Each item is quoted with 1 point if the answer is in the sense of social desirability and 0 points if it is in the opposite direction. Prior to data analyses, all participants were screened for social desirability, ruling out adolescents who scored over M = 14.73, which corresponds to two standard deviations above the mean, as suggested by Almiro et al. (2016), as they showed a tendency to transmit socially desirable responses rather than choosing responses that were a true reflection of their behaviors or feelings [38]. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.68.

2.1.3. Dating Violence Perpetration

Adolescents were asked two questions regarding several violent behaviors: (a) “Have you ever been violent towards anyone?” and (b) “With whom?”. For these two questions, the adolescents answered if it was physical violence, psychological violence, sexual violence, control behavior violence, and severe pattern of behavior violence (e.g., threatening and mutilating). Answers were rated as 0 = No, 1 = Yes, and the victim (e.g., romantic relationship—girlfriend/boyfriend). Thus, DVP is a dichotomous variable that classifies participants as juveniles who have committed aggressive behavior (JAB) and juveniles who have not committed aggressive behavior (JNAB).

2.1.4. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

To assess childhood trauma, the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al. [39], Portuguese version by Dias et al. [40]), was used. CTQ is a 28-item questionnaire aimed to quantify self-reported childhood trauma history in adolescent and adult populations (from 12 years old). Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Never true”) to 5 (“Very often true”). Childhood trauma was measured using five subscales: Emotional abuse (e.g., “I thought that my parents wished I had never been born”; α = 0.83), Emotional neglect (e.g., “I felt loved”; α = 0.84), Sexual abuse (e.g., “I believe that I was sexually abused”; α = 0.91), Physical abuse (e.g., “I believe that I was physically abused”; α = 0.87), and Physical neglect (e.g., “I don’t have enough to eat”; α = 0.65). Each subscale contains five items, and an additional three items are intended to measure any tendency to minimize or deny the abuse.

2.1.5. Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire

The Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ [28], Portuguese version by Carvalho [41]), contained 168 items assessing 14 scales, and the number of items assessing each scale ranged from 10 to 13. Items were designed to be concrete and relevant to the experience of middle schoolers without being too narrow in applicability or gender-specific [28]. The questionnaire used a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (“Very False”) to 5 (“Very True”). In the present study, the Portuguese version of the EATQ was used, consisting of 65 items, each answered on a 5-point graded scale, from “almost never applies to you” to “almost always applies to you”. The instrument is composed of two dimensions and five respective categories: temperament (i.e., self-regulation, reactivity, and emotionally), and behavior (i.e., aggression and depressive mood). In this study, the EATQ revealed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 in temperament subscale.

3. Procedure

The participants were students from Portuguese schools. In addition to the institutional authorization from the Portuguese Ministry of Education, all participants were informed of the goals of the study, and the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses were guaranteed. The research protocol was approved by a university ethics committee. Written consent was collected from participants’ parents/legal guardians. Data collection took place through computer-based questionnaires that participants would complete, in quiet classrooms, using an Internet-based survey hosted on a secure institutional server. Participation was voluntary and did not involve any monetary payment or delivery of material goods.

4. Analytic Plan

The present study has a methodological aspect to be quantitative and cross-sectional, which was realized at the time of data collection. Data was analyzed by using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). First, instruments were categorized, and dimensions were constructed in each. Missing values were identified and removed to not bias the effects of the statistical analysis. To be able to compare perpetrators from nonperpetrators, from the 3803 participants, there were 2206 selected adolescents who self-reported engagement in DVP, and 1291 adolescents self-reported no engagement in such behaviors.

After checking and ensuring the assumptions of normality and homogeneity, the statistical analysis was carried out. The Pearson and Spearman Correlation Coefficient (r) was used to determine the degree of association between the variables. The hypothesis was tested using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro, testing the mediating effect of temperament on the relationship between childhood trauma and DVP. The PROCESS macro uses the product of coefficients approach to test indirect effects and Monte Carlo confidence intervals to determine the significance of the indirect effects. The bootstrap confidence intervals determine if the effects on Model 4 are significant, which is the case if they do not include zero [42]. The bootstrap method does not require a normal distribution assumption and provides a more powerful test than other traditional methods based on formulas with a normality assumption [42].

5. Results

5.1. Preliminary Analyses

Means and SDs for the study variables are reported in Table 1. The total score for the CTQ showed that there were significant differences (t (3401.118) = −14.561, p = 0.000, and d = 0.49) in the scores between juveniles who have committed aggressive behavior (JAB) (M = 50.42, SD = 13.15) and juveniles who have not committed aggressive behavior (JNAB) (M = 44.93, SD = 9.09) in a relationship. For each subscale, namely, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse, and physical abuse, it was possible to find that JAB in a relationship had higher scores than JNAB. Regarding the EATQ total score, significant differences were found (t (2694.798) = −4.168, p = 0.000, and d = 0.15) between the group of JAB in a relationship (M = 196.78, SD = 29.91) having a higher score than JNAB (M = 192.40, SD = 29.99). For each subscale, it was found that when it comes to the subscale belonging/affiliation, fear, and self-regulation, there were no significant differences between JAB and JNAB in a relationship. Regarding aggression, depressive mood, frustration, perceptive sensitivity, and behavior subscales, the results show significant differences where JAB presented a high score in comparison to JNAB in a relationship. However, for the subscales of pleasurable sensitivity (t (3495) = 3.004, p = 0.003, and d = 0.11) and temperament (t (2531.345) = 3.162, p = 0.002, and d = 0.01), JAB presented lower scores than JNAB (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Group Differences for Childhood Trauma and Temperament in Dating Violence.

5.2. Correlation Analyses

A series of correlation analyses were used to test the association between DVP (i.e., dichotomic variable composed of JAB and JNAB groups), childhood trauma, and temperament (see Table 2). The results show that temperament was negatively correlated with every dimension of childhood trauma, except emotional abuse. In addition, DVP was positively correlated with every dimension of childhood trauma and negatively correlated with temperament.

Table 2.

Correlations (r) among Variables of Interest.

5.3. Mediation Analyses

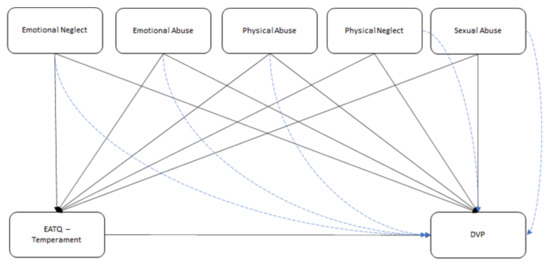

Childhood trauma was selected as the independent variable; DVP was defined as the dependent variable, and temperament was considered the mediator. Mediation effects were measured using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, [42]; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Statistical mediation effects.

According to the obtained results, it was found that emotional neglect (β = −1.33, SE = 0.06, and p < 0.000) had a negative and significant relationship with temperament. The relationship between emotional neglect and DVP was positive and significant (β = 0.06, SE = 0.01, and p < 0.000), but the relationship between temperament and DVP was found to be negative and not significant (β = −0.00, SE = 0.00, and p = 0.90). The indirect effect between emotional neglect and DVP was not mediated by temperament (Indirect Effect = 0.00, SE = 0.00, 95% CI = [−0.01, 0.01]). Therefore, hypothesis 1, regarding the dimension of emotional neglect, was not supported, indicating that temperament was not a mediator on the relationship between emotional neglect and DVP.

It was found that emotional abuse (β = 0.18, SE = 0.06, and p < 0.013) had a positive and significant relationship with temperament. The relationship between emotional abuse and DVP was positive and significant (β = 0.15, SE = 0.01, and p < 0.000), and the relationship between temperament and DVP was negative and significant (β = −0.01, SE = 0.00, and p < 0.000). The indirect effect between emotional abuse and DVP was found to be mediated by temperament (Indirect Effect = −0.00, SE = 0.00, 95% CI = [−0.00, −0.000]). Therefore, temperament partially mediated the relationship between emotional abuse and DVP, supporting the presented hypothesis 2.

It was found that physical abuse had a negative and significant relationship with temperament (β = −0.40, SE = 0.06, p < 0.000). The relationship between physical abuse and DVP was positive and significant (β = 0.17, SE = 0.02, and p < 0.000), and the relationship between temperament and DVP was negative and significant (β = −0.00, SE = 0.00, and p = 0.022). The indirect effect between physical abuse and DVP was mediated by temperament (Indirect Effect = 0.00, SE = 0.00, 95% CI = [0.00, 0.00]). Therefore, hypothesis 3 was supported, indicating that temperament partially mediated the relationship between physical abuse and DVP.

In addition, it was found that physical neglect had a negative and significant relationship with temperament (β = −1.90, SE = 0.10, and p < 0.000). The relationship between physical neglect and DVP was positive and significant (β = 0.09, SE = 0.01, and p < 0.000), and the relationship between temperament and DVP was negative and significant (β = −0.00, SE = 0.00, and p = 0.394). The indirect effect between physical neglect and DVP was not mediated by temperament (Indirect Effect = 0.00, SE = 0.00, 95% CI = [−0.00, 0.01]). Therefore, hypothesis 4 was not supported, indicating that temperament was not a mediator on the relationship between physical neglect and DVP.

Finally, regarding sexual abuse, it was possible to find a negative and significant relationship with temperament (β = −0.57, SE = 0.06, and p < 0.000). The relationship between sexual abuse and DVP was positive and significant (β = 0.14, SE = 0.02, and p < 0.000), and the relationship between temperament and DVP was negative and significant (β = −0.00, SE = 0.00, and p = 0.022). The indirect effect between sexual abuse and DVP was mediated by temperament (Indirect Effect = 0.00, SE = 0.00, 95% CI = [0.00, 0.01]). Therefore, hypothesis 5 was supported, revealing that temperament partially mediated the relationship between sexual abuse and DVP.

6. Discussion

Dating violence reveals itself to be a problem of great importance in society, tending to manifest in the marital context. The main objective of this study was to understand the rationale behind dating violence perpetration (DVP), since its prevalence has been predominant amongst adolescents and, due to the lack of research that may explain it, through the analysis of the mediating role of temperament in the relationship between childhood trauma and DVP.

The present study found that the dimensions of childhood trauma, such as emotional neglect, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, had a positive and significant relationship with DVP. Research suggests that childhood trauma can cause psychological harm to the child [4], creating distance between its caregiver and causing the development of an insecure attachment that later can make the child more susceptible to low self-esteem, known as a risk factor for DVP [43]. Previous research highlights that DVP is a common problem in adolescents as a form of externalization of aggressive behavior due to experiences related to childhood trauma [4,5,44]. In addition, one of the main reasons for the perpetration of these behaviors can be associated with children tending to imitate their parents or caregivers’ antisocial characteristics and internalize aggressive behavior as a normative response [5]. According to Sansone et al. [44], children who witness violence during their childhood can become violent or aggressive individuals later in life.

Regarding temperament, it was found that it has a major role as a mediator in the relationship between all dimensions of childhood trauma and DVP, having a positive and significant impact on it. These findings meet previous research on the subject where difficult temperament can contribute to the development of aggressive behavior [1,27,29]. Therefore, it is possible to identify two developmental pathways: (a) problems with emotional regulation and (b) problems with low emotional arousal [30,31]. Sometimes, partners in a relationship go through periods of anger, jealousy, and confusion [5], having difficulty controlling their negative emotions. It is possible that perpetrators have problems with excessive emotional reactivity, having difficulty responding in adaptative, flexible, and age-appropriate ways to stressors that can lead to aggressive behaviors. The excessive emotional reactivity can interfere with their social problem-solving skills, making them react impulsively in decision-making situations, adopting aggressive actions to resolve their problems in the relationship. In fact, refraining from engaging in aggressive behaviors in a relationship may require greater self-regulation skills [45]. Another explanation can be related to low levels of emotional arousal [31]. Having a reduction in autonomic activity, perpetrators may show a tendency to engage in high-risk behaviors to experience the same feelings as typical adolescents, which may interfere with the development of conscience and the capacity of moral reasoning [46], since they do not seem to experience typical fear and guilt regarding their violent behavior. In this sense, DVP can use aggression and manipulation to solve problems due to their lack of guilt and lack of moral reasoning.

Although temperament plays a mediating role in the relationship between emotional abuse and DVP, the results are contrary to the literature. According to the obtained results, the relationship between temperament and DVP was negative and significant. These results indicate that experiencing emotional abuse during childhood enhances the probability of developing temperament, and, in turn, temperament decreases DVP. According to Lang et al. [47], maternal emotional abuse was associated with low levels of frustration and fast recovery from distress in infants, which may explain the relationship between emotional abuse and temperament.

Several limitations were found throughout this study. First, considering that the present study investigated a largely functional sample with a cross-sectional approach, it is recommended that future studies consider these findings to establish a clearer way through the approach of longitudinal studies to understand possible variations over time. It is also important to investigate the relationship between emotional abuse and temperament since the results did not support the existing literature. Second, the data collection was performed using self-report instruments, incurring the risk of its content being perceived in a participatory manner and the risk of omission by the participants.

7. Conclusions

From a clinical point of view, future research should take into consideration investigations of longitudinal nature to better understand the problem. In addition, the present findings can help refine cognitive and emotional strategies to end and prevent the cycle of violence perpetration in dating and possibly marital contexts. In this sense, instead of focusing on identifying warning signs that may constitute abuse, interventions can focus on how reactions can be attenuated in the moment to prevent aggressive behaviors. Adolescence is a period of growth in social and affective processing that may increase vulnerability to engaging impulsively in disruptive behaviors, and these interventions could include cognitive behavioral therapy and de-escalation tools (e.g., mindfulness strategies) or even the development of biosensor technologies providing immediate feedback following the detection of heightened emotions [48].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B., E.R. and P.F.; methodology, R.B., E.R. and P.F.; software, E.R. and P.F.; validation, I.M., R.B., E.R. and P.F.; formal analysis, I.M., R.B., E.R. and P.F.; investigation, R.B., E.R. and P.F.; resources, R.B., E.R. and P.F.; data curation, I.M., R.B., E.R. and P.F.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M., R.B., E.R. and P.F.; writing—review and editing, I.M., R.B., E.R. and P.F.; visualization, I.M., R.B., E.R. and P.F.; supervision, R.B.; project administration, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (protocol code 76/2018; 19 November 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, C.; Stith, S. Factors predicting dating violence perpetration among male and female college students. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2008, 17, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivolo-Kantor, A.; Massetti, G.; Niolon, P.; Foshee, V.; Reyes, L. Relationship characteristics associated with teen dating violence perpetration. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2016, 25, 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, R.; Ramião, E.; Figueiredo, P.; Araújo, A. Abusive sexting in adolescence: Prevalence and characteristics of abusers and victims. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 610474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertürk, I.; Kahya, Y.; Gör, N. Childhood maltreatment and aggression: The mediator role of the early maladaptive schema domains and difficulties in emotion regulation. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2018, 29, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.; Maxwell, S. Assessing the effects of witnessed parental conflict and guilt on dating violence perpetration among south Korean college students. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 36, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, X.B.; Foshee, V.A. Adolescent dating violence: Do adolescents follow in their friends’, or their parents’, footsteps? J. Interpers. Violence 2004, 19, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, N.; Oliffe, J.L.; Bungay, V.; Kelly, M.T. Male perpetration of adolescent dating violence: A scoping review. Am. J. Men’s Health 2020, 14, 1557988320963600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, R.; Ramião, E.; Figueiredo, P. Parental violence before, during and after COVID-19 lockdown. Psicologia 2022, 36, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Widom, C.S.; Wilson, H.W. Intergenerational Transmission of Violence. In Violence and Mental Health; Lindert, J., Levav, I., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, T.S.; McBain, R.K.; Newnham, E.A.; Brennan, R.T. The intergenerational impact of war: Longitudinal relationships between caregiver and child mental health in postconflict Sierra Leone. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Gómez, J. The sound of barking dogs: Violence and terror among Salvadoran families in the postwar. Med. Anthropol. Q. Int. J. Anal. Health 2002, 16, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, E.; Sturzenhofecker, G.; Sanabria, H.; Johnson, B.D. Mothers and daughters: The intergenerational reproduction of violence and drug use in home and street life. J. Ethn. Subst. Abus. 2004, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, S.; Zimmerman, M.A. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman-Smith, D.; Tolan, P. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Dev. Psychopathol. 1998, 10, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.; LaNoue, M.; Lee, C.; Freeland, L.; Freund, R. Involving parents in a community-based, culturally grounded mental health intervention for American Indian youth: Parent perspectives, challenges, and results. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 40, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, F.; Farrington, D.P. Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, S68–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.B.J.; Van Brakle, M. The everyday struggle: Social capital, youth violence and parenting strategies for urban, low-income black male youth. Race Soc. Probl. 2013, 5, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, K.; Nuttall, A.K.; Comas, M.; Borkowski, J.G.; Akai, C.E. Intergenerational continuity of child abuse among adolescent mothers: Authoritarian parenting, community violence, and race. Child Maltreat. 2012, 17, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Cicchetti, D. An ecological-transactional analysis of children and contexts: The longitudinal interplay among child maltreatment, community violence, and children’s symptomatology. Dev. Psychopathol. 1998, 10, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palosaari, E.; Punamaki, R.; Qouta, S.; Diab, M. Intergenerational effects of war trauma among Palestinian families mediated via psychological maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, E.M.; Taylor, L.K.; Merrilees, C.E.; Goeke-Morey, M.C.; Shirlow, P. Emotional insecurity in the family and community and youth delinquency in Northern Ireland: A person-oriented analysis across five waves. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R.; Shaver, P. Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2000, 42, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and Anger; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala, J.; Zdaniuk, B. Adult attachment styles and aggressive behavior within dating relationships. J. Interpers. Violence 1998, 17, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, B. An adult attachment theoretical perspective of gender symmetry in intimate partner violence. Sex Roles 2005, 24, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortis, M.; Gándara, V. Study on the relations between temperament, aggression, and anger in children. Aggress. Behav. 2006, 32, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, S.; Rothbart, M. Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. J. Early Adolesc. 1992, 13, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahey, B.; Hulle, C.; Keenan, K.; Rathouz, P.; D’Onofrio, B.; Rodgers, J.; Waldman, I. Temperament and parenting during the first year of life predict future child conduct problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008, 36, 1139–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P. Developmental pathways to conduct disorders: Implications for serving youth who show severe aggressive and antisocial behavior. Psychol. Sch. 2004, 41, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.; Morris, A. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004, 33, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostlund, B.; Myruski, S.; Buss, K.; Pérez-Edgar, K. The centrality of temperament to the research domain criteria (RDoC): The earliest building blocks of psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 33, 1584–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, H.L.M.; Foshee, V.A.; Fortson, B.L.; Valle, L.A.; Breiding, M.J.; Merrick, M.T. Longitudinal Mediators of Relations Between Family Violence and Adolescent Dating Aggression Perpetration. J. Marriage Fam. 2015, 77, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouriles, E.N.; McDonald, R.; Mueller, V.; Grych, J.H. Youth experiences of family violence and teen dating violence perpetration: Cognitive and emotional mediators. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 15, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J. Conduct Disorders and Severe Antisocial Behavior; Plenum Press: Boston, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, R.; Figueiredo, P.; Ramião, E. Intervenção no âmbito da violência nas relações de namoro: Resultados preliminares do projeto Violentómetro. In Violências no Namoro; Neves, S., Correia, A., Eds.; Edições ISMAI: Maia, Portugal, 2018; pp. 153–174. [Google Scholar]

- Almiro, P.; Almeida, D.; Ferraz, M.; Ferreira, R.; Perdiz, C.; Dias, I.; Gonçalves, S.; Simões, M. Escala de desejabilidade social de 20 itens (EDS-20) [20-item social desirability scale]. In Avaliação Psicológica em Contextos Forenses: Instrumentos Validados Para Portugal; Psychological Assessment in Forensic Contexts: Validated Instruments for Portugal; Simões, M., Almeida, L., Gonçalves, M., Eds.; Pactor/Lidel: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, P. Social desirability bias. In International Encyclopedia of Marketing; Sheth, J.N., Malhotra, N.K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Newcomb, M.D.; Walker, E.; Pogge, D.; Ahluvalia, T.; Stokes, J.; Handelsman, L.; Medrano, M.; Desmond, D.; et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.; Sales, L.; Carvalho, A.; Castro-Vale, I.; Kleber, R.; Cardoso, R.M. Estudo de propriedades psicométricas do questionário de trauma de infância—Versão breve numa amostra portuguesa não clínica. Laboratório Psicol. 2013, 11, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.A. Vinculação, Temperamento e Processamento de Informação: Implicações nas Perturbações Emocionais e Comportamentais no Início da Adolescência. Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto de Educação e Psicologia, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, A.; Paradis, A.; Todorov, E.; Blais, M.; Hébert, M. Trajectories of psychological dating violence perpetration in adolescence. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 97, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.; Leung, J.; Wiederman, M. Five forms of childhood trauma: Relationships with aggressive behavior in adulthood. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012, 14, 27279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Courtain, A.; Glowacz, F. Youth’s conflict resolution strategies in their dating relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchaine, T.; Hinshaw, S. Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 3rd ed.; John Wiley Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A.; Gartstein, M.; Rodgers, C.; Lebeck, M. The impact of maternal childhood abuse on parenting and infant temperament. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 23, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, P.; Ridenour, T.; Chung, S.; Adhia, A.; Grieb, S.; Poole, E.; Huettner, S.; Rothman, E.; Merritt, M. Adolescent and young women’s daily reports of emotional context and episodes of dating violence. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).