Smartphone Use and Mental Health among Youth: It Is Time to Develop Smartphone-Specific Screen Time Guidelines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

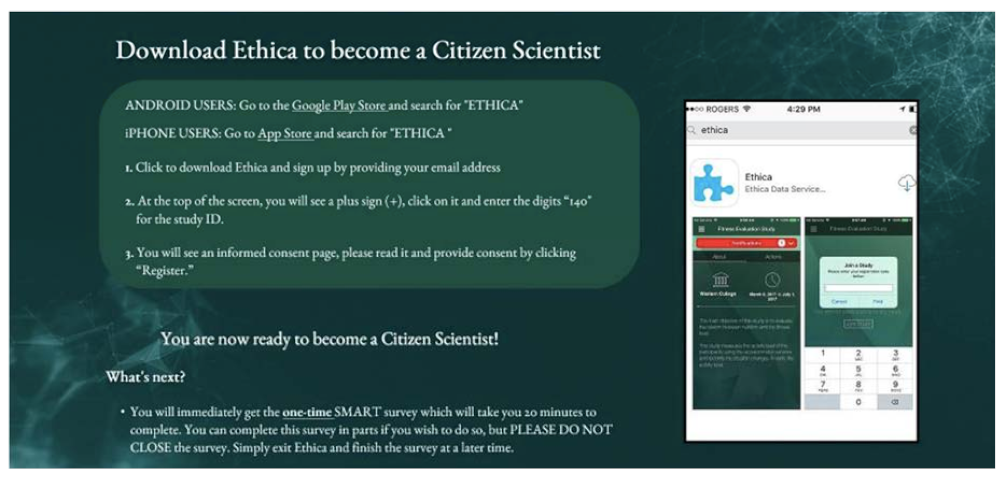

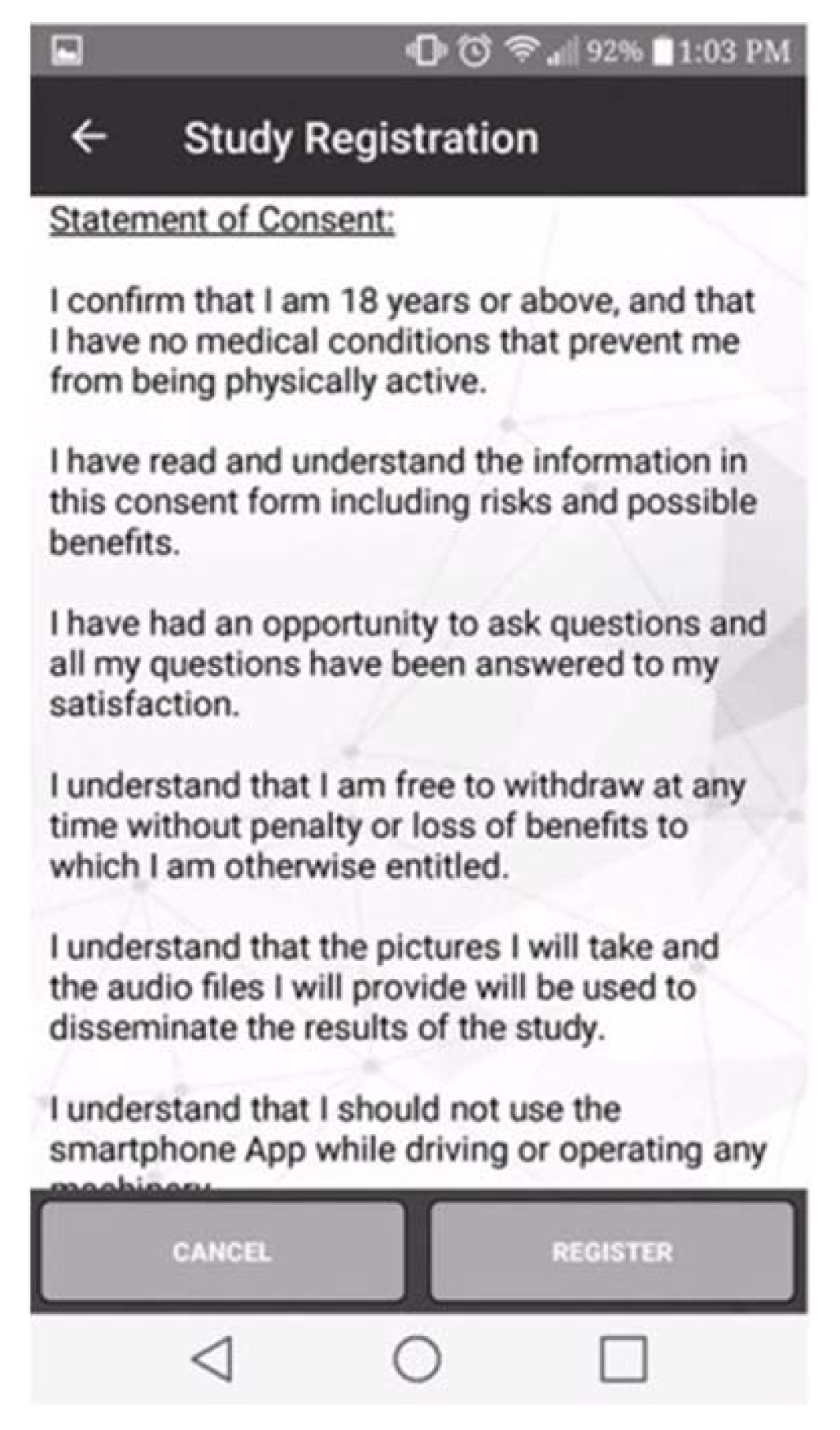

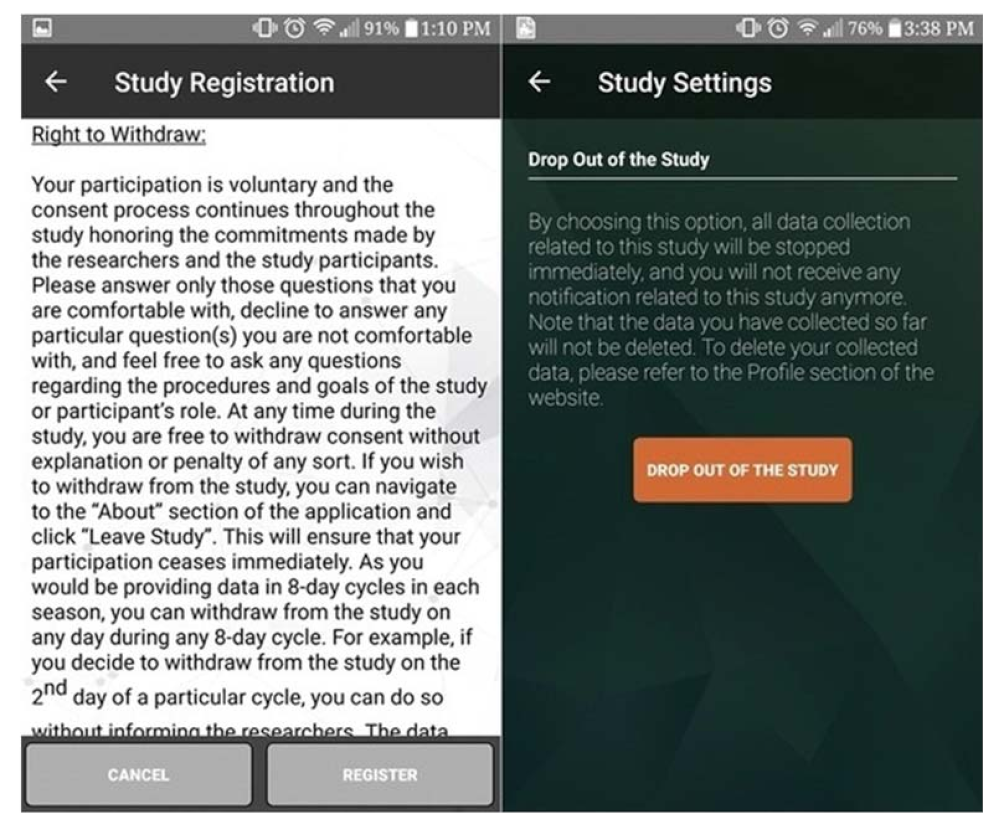

2.1. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data and Risk Management

3. Measures

3.1. Smartphone Use (Independent Variables)

3.2. Mental Health Problems (Dependent Variables)

3.3. Subjective Mental Health (Dependent Variables)

3.4. Control Variables

4. Statistical Analyses

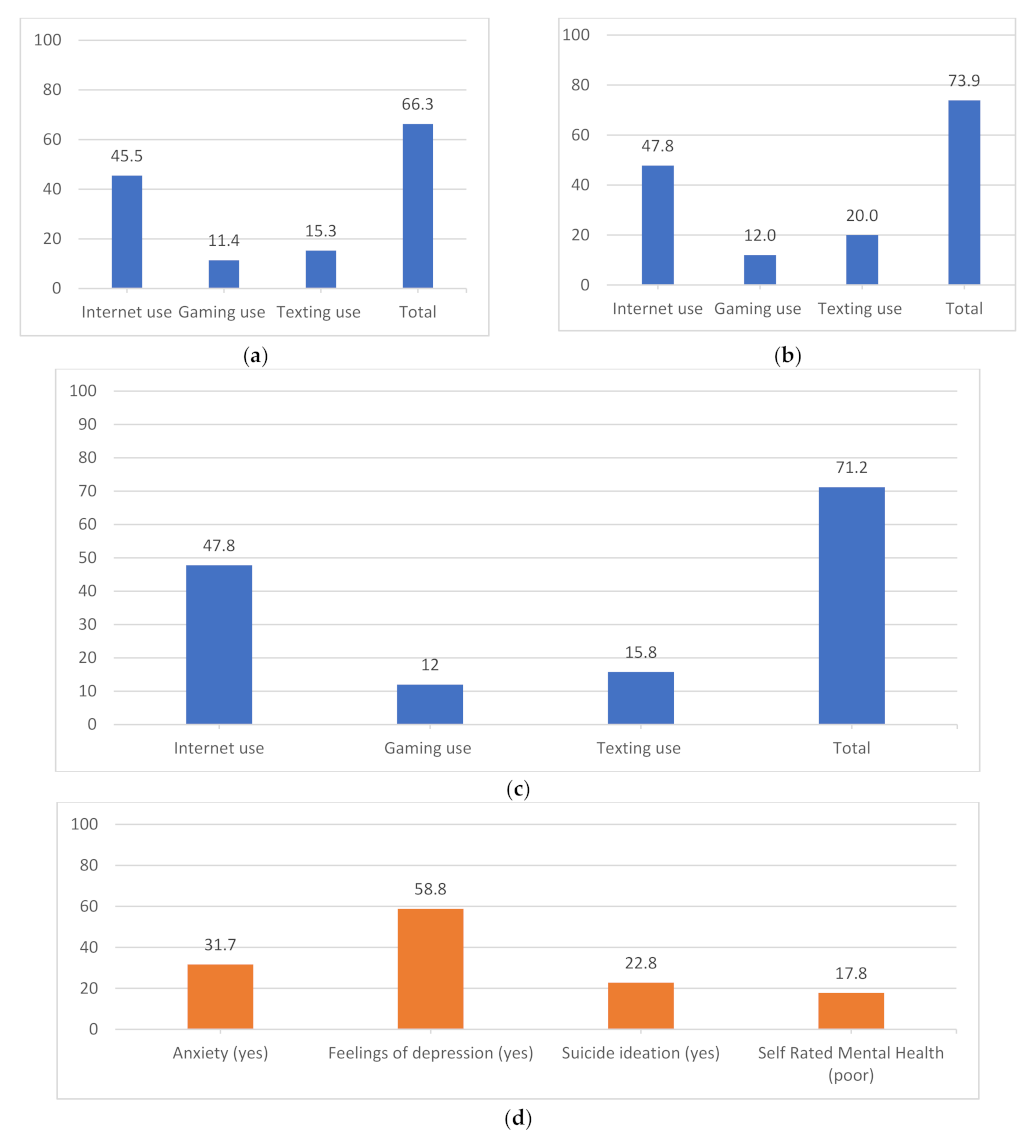

5. Results

6. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Number of Smartphone Users from 2016 to 2021 (In Billions) 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/ (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Anderson, M.; Jiang, J. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew. Res. Cent. 2018, 31, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Abi-Jaoude, E.; Naylor, K.T.; Pignatiello, A. Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E136–E141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoare, E.; Milton, K.; Foster, C.; Allender, S. The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N.; Campbell, W.K. Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion 2018, 18, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, N.; Viner, R.M. Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javed, S.; Azmi, S.A.; Khan, S.M. Electronic screen use and Mental Well-Being in Early Adolescents. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2017, 20, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell, K.E.; Flament, M.F.; Buchholz, A.; Henderson, K.A.; Obeid, N.; Schubert, N.; Goldfield, G.S. Examining the bidirectional relationship between physical activity, screen time, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time during adolescence. Prev. Med. 2016, 88, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomée, S. Mobile phone use and mental health. A review of the research that takes a psychological perspective on exposure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vahedi, Z.; Saiphoo, A. The association between smartphone use, stress, and anxiety: A meta-analytic review. Stress Health 2018, 34, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwood, S.; Anglim, J. Problematic smartphone usage and subjective and psychological well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David, M.E.; Roberts, J.A.; Christenson, B. Too Much of a Good Thing: Investigating the Association between Actual Smartphone Use and Individual Well-Being. Int. J. Human-Comput. Interact. 2017, 34, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A. Cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.G.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin. Q. 1973, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Hall, B.J.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D. Types of smartphone usage and relations with problematic smartphone behaviors: The role of content consumption vs. socialsmartphone use. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marty-Dugas, J.; Smilek, D. The relations between smartphone use, mood, and flow experience. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020, 164, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, A. The Psychology of Addictive Smartphone Behavior in Young Adults: Problematic Use, Social Anxiety, and Depressive Stress. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetta, E.; Harkin, L.; Billieux, J.; Kanjo, E.; Kuss, D.J. Problematic smartphone use: An empirically validated model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 100, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, R.; Pandey, N.; Pal, A. Impact of digital surge during COVID-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Saskatchewan. Public Health Orders|Public Measures|Government of Saskatchewan 2020. Available online: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/health-care-administration-and-provider-resources/treatment-procedures-and-guidelines/emerging-public-health-issues/2019-novel-coronavirus/public-health-measures/public-health-orders#current-public-health-orders (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- United Nations. UN/DESA Policy Brief #61: COVID-19: Embracing Digital Government during the Pandemic and Beyond|Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-61-covid-19-embracing-digital-government-during-the-pandemic-and-beyond/ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Clark, B. Cellular phones as a primary communications device: What are the implications for a global community? Glob. Med. J. 2013, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Katapally, T.R.; Chu, L.M. Methodology to derive objective screen-state from smartphones: A smart platform study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katapally, T.R. A global digital citizen science policy to tackle pandemics like COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katapally, T.R.; Bhawra, J.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Ferguson, L.; Longo, J.; Rainham, D.; Larouche, R.; Osgood, N. The Home of the SMART Platform: A Digital Epidemiological and Citizen Science Initiative—A big data toolkit for digital health, precision medicine, and social innovation. JMIR Public Heal. Surveill. 2018, 4, e31. Available online: https://tarunkatapally.com/the-smart-platform/ (accessed on 25 January 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katapally, T.R. The SMART framework: Integration of citizen science, community-based participatory research, and systems science for population health science in the digital age. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, D.L.; Stanley, K.G.; Osgood, N.D. A field-validated architecture for the collection of health-relevant behavioural data. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics, Verona, Italy, 15–17 September 2014; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, A.; Sizo, A.; Qian, W.; Knowles, A.D.; Tavassolian, A.; Stanley, K.; Bell, S. Exploring mobility indoors: An application of sensor-based and GIS systems. Trans. GIS 2014, 18, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, M.; Stanley, K.G.; Knowles, D.L.; Calver, J.; Osgood, N.D. Human network data collection in the wild: The epidemiological utility of micro-contact and location data. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium, Miami, FL, USA, 28–30 January 2012; pp. 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapally, T.R.; Hammami, N.; Chu, L.M. A randomized community trial to advance digital epidemiological and mHealth citizen scientist compliance: A smart platform study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, D.E.; Norman, G.J.; Wagner, N.; Patrick, K.; Calfas, K.J.; Sallis, J.F. Reliability and validity of the sedentary behavior questionnaire (SBQ) for adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Janssen, I.; Kho, M.E.; Hicks, A.; Murumets, K.; Colley, R.C.; Duggan, M. Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for Children and Youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Löwe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; Spitzer, C.; Glaesmer, H.; Wingenfeld, K.; Schneider, A.; Brähler, E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Monahan, P.O.; Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 2017 Standard Questionnaire Item Rationale; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp: College Station, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, S.; Rees, P.; Wildridge, B.; Kalk, N.J.; Carter, B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: A systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rideout, V.; Robb, M.B. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens; Common Sense Media: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kleppang, A.L.; Steigen, A.M.; Ma, L.; Finbråten, H.S.; Hagquist, C. Electronic media use and symptoms of depression among adolescents in Norway. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandola, A.; Owen, N.; Dunstan, D.W.; Hallgren, M. Prospective relationships of adolescents’ screen-based sedentary behaviour with depressive symptoms: The Millennium Cohort Study. Psychol. Med. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wu, L.; Yao, S. Dose–response association of screen time-based sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents and depression: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 50, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daugherty, D.A.; Runyan, J.D.; Steenbergh, T.A.; Fratzke, B.J.; Fry, B.N.; Westra, E. Smartphone delivery of a hope intervention: Another way to flourish. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heron, K.E.; Smyth, J.M. Ecological momentary interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapally, T.R.; Rainham, D.; Muhajarine, N. Factoring in weather variation to capture the influence of urban design and built environment on globally recommended levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity in children. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e009045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katapally, T.R.; Rainham, D.; Muhajarine, N. The Influence of Weather Variation, Urban Design and Built Environment on Objectively Measured Sedentary Behaviour in Children. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Proportion (in Percent) | Frequency (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Grade | ||

| 9 | 29.7 | 125 |

| 10 | 20.4 | 86 |

| 11 | 14.5 | 61 |

| 12 | 35.4 | 149 |

| School | ||

| 1 | 25.3 | 110 |

| 2 | 17.1 | 74 |

| 3 | 11.5 | 50 |

| 4 | 18.0 | 78 |

| 5 | 28.1 | 122 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Indigenous | 5.0 | 21 |

| Canadian | 39.8 | 166 |

| Other | 55.2 | 230 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 55.7 | 233 |

| Male | 38.5 | 161 |

| Transgender/other/did not disclose | 5.7 | 24 |

| Mean | SD | |

| Age | 16.0 | 1.8 |

| Weekly Smartphone Use b | Weekend Day Smartphone Use c | Weekday Smartphone Use c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

| Internet use | 1.27 | (0.77–2.10) | 1.36 | (0.84–2.22) | 1.20 | (0.73–2.00) |

| Gaming use | 1.62 | (0.77–3.40) | 1.45 | (0.70–3.00) | 1.72 | (0.81–3.65) |

| Texting use | 1.57 | (0.82–3.03) | 1.37 | (0.77–2.42) | 1.50 | (0.80–2.96) |

| Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||

| Total smartphone use | 1.83 * | (1.06–3.15) | 1.71 | (0.97–3.00) | 1.88 * | (1.13–3.13) |

| Weekly Smartphone Use b | Weekend Day Smartphone Use c | Weekday Smartphone Use c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | |

| Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | ||||

| Internet use | 1.16 | (0.66–2.03) | 0.99 | (0.58–1.71) | 1.00 | (0.58–1.75) |

| Gaming use | 1.64 | (0.76–3.54) | 2.90 ** | (1.39–6.03) | 1.79 | (0.82–3.88) |

| Texting use | 1.69 | (0.85–3.36) | 1.25 | (0.67–2.30) | 1.66 | (0.83–3.30) |

| Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | ||||

| Total smartphone use | 1.58 | (0.87–2.89) | 2.57 ** | (1.28–5.15) | 1.66 | (0.94–2.92) |

| Weekly Smartphone Use b | Weekend Day Smartphone Use c | Weekday Smartphone Use c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | |

| Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | ||||

| Internet use | 0.85 | (0.53–1.35) | 0.90 | (0.57–1.41) | 1.07 | (0.67–1.70) |

| Gaming use | 0.53 | (0.26–1.07) | 0.39 * | (0.19–0.79) | 0.51 | (0.250–1.06) |

| Texting use | 0.65 | (0.35–1.23) | 0.69 | (0.40–1.19) | 0.67 | (0.35–1.26) |

| Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | ||||

| Total smartphone use | 0.40 *** | (0.25–0.67) | 0.27 *** | (0.16–0.47) | 0.54 ** | (0.34–0.85) |

| Weekly Smartphone Use b | Weekend Day Smartphone Use c | Weekday Smartphone Use c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | |

| Model 19 | Model 20 | Model 21 | ||||

| Internet use | 1.30 | (0.71–2.40) | 1.65 | (0.91–2.98) | 1.15 | (0.63–2.10) |

| Gaming use | 1.02 | (0.40–2.63) | 1.03 | (0.40–2.64) | 1.13 | (0.44–2.92) |

| Texting use | 0.89 | (0.39–2.05) | 0.66 | (0.31–1.41) | 0.82 | (0.35–1.91) |

| Model 22 | Model 23 | Model 24 | ||||

| Total smartphone use | 1.87 | (0.93–3.74) | 2.67 * | (1.20–5.96) | 1.68 | (0.89–3.16) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brodersen, K.; Hammami, N.; Katapally, T.R. Smartphone Use and Mental Health among Youth: It Is Time to Develop Smartphone-Specific Screen Time Guidelines. Youth 2022, 2, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010003

Brodersen K, Hammami N, Katapally TR. Smartphone Use and Mental Health among Youth: It Is Time to Develop Smartphone-Specific Screen Time Guidelines. Youth. 2022; 2(1):23-38. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrodersen, Kayla, Nour Hammami, and Tarun Reddy Katapally. 2022. "Smartphone Use and Mental Health among Youth: It Is Time to Develop Smartphone-Specific Screen Time Guidelines" Youth 2, no. 1: 23-38. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010003

APA StyleBrodersen, K., Hammami, N., & Katapally, T. R. (2022). Smartphone Use and Mental Health among Youth: It Is Time to Develop Smartphone-Specific Screen Time Guidelines. Youth, 2(1), 23-38. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010003