Western Individualism and the Psychological Wellbeing of Young People: A Systematic Review of Their Associations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

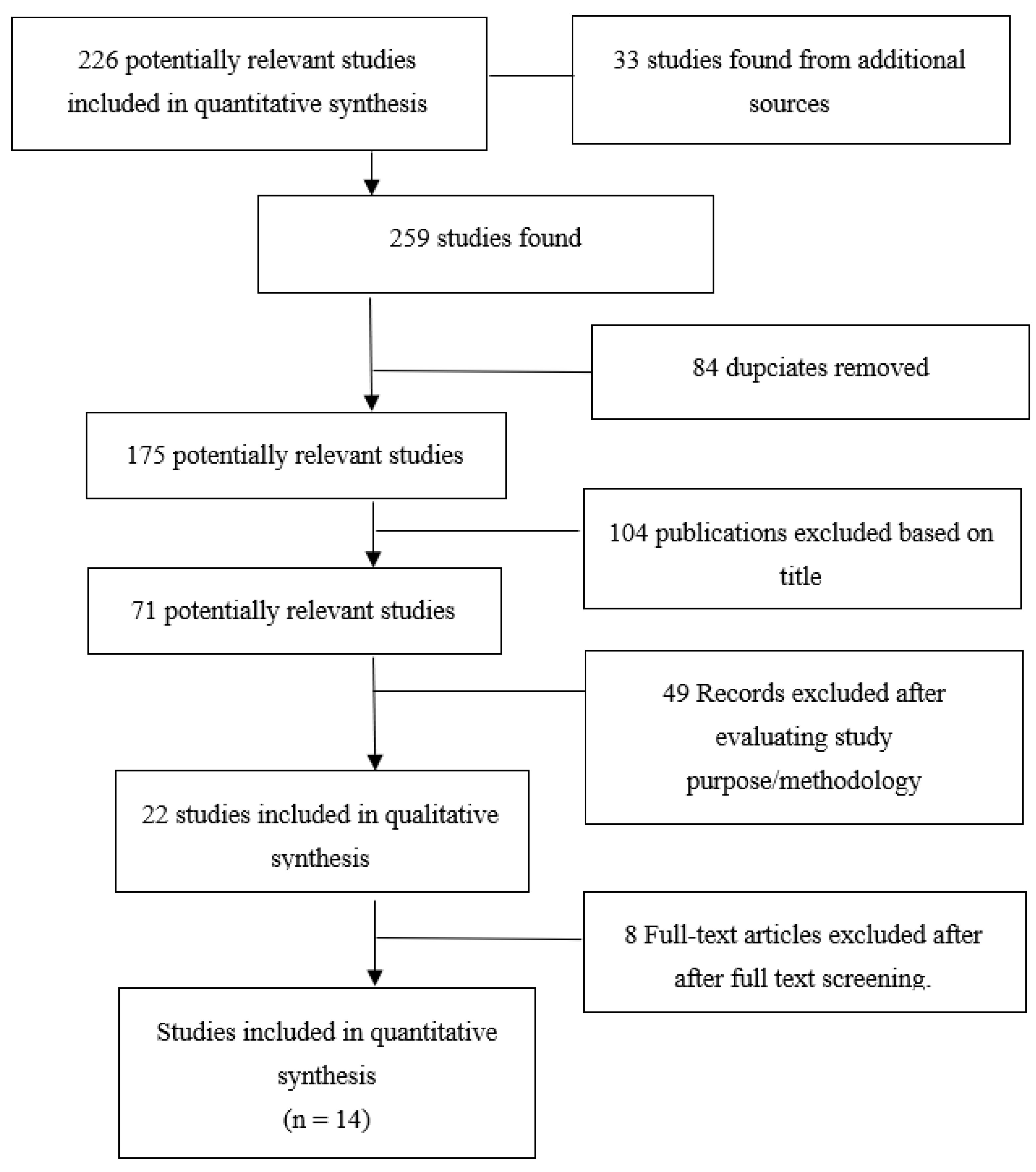

2. Methods

3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

4. Findings

4.1. Characteristics of the Studies Reviewed

Instruments and Methods Used

5. Results

Findings: Individualism and Wellbeing

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Implications of Findings for Further Research

6.3. Limitations of the Review

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Twenge, J.M.; Cooper, A.B.; Joiner, T.E.; Duffy, M.E.; Binau, S. Age, Period, and Cohort Trends in Mood Disorder Indicators and Suicide-Related Outcomes in a Nationally Representative Dataset, 2005–2017. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collishaw, S. Annual Research Review: Secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collishaw, S.; Maughan, B.; Natarajan, L.; Pickles, A. Trends in adolescent emotional problems in England: A comparison of two national cohorts twenty years apart. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Gentile, B.; Dewall, N.; Ma, D.; Lacefield, K.; Schurtz, D. Birth cohort increases in psychopathology among young Americans, 1938–2007: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the MMPI. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M. Generational Differences in Mental Health: Are Children and Adolescence Suffering More, or Less? Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R. A New Narrative of Young People’s Health and Wellbeing. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezlek, J.; Humphrey, A. Individualism, Collectivism, and Well-being Among a Sample of Young Americans. Emerg. Adulthood. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K.; Freeman, T. Generational Differences in Young Adults Life Goals, Concern for Others, and Civic Orientation, 1966–2009. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Triandis, H.; Gelfland, M. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; Revised and Expanded 3rd Edition; McGraw-Hill USA: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Christoffersen, K.; Davidson, H.; Snell, P. Lost in Translation: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, A.; Forbes-Mewett, H. Social Value Systems and the Mental Health of International Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Int. Stud. 2021, 11, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Diener, M.; Diener, C. Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrindell, W.A.; Hatzichristou, C.; Wensink, J.; Rosenberg, E.; Van Twillert, B.; Stedema, J.; Meijer, D. Dimensions of national culture as predictors of cross-national differences in subjective well- being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1997, 23, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, P. Cross-national differences in happiness: Economic and cultural factors explored. Soc. Indic. Res. 1998, 43, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. Quality of life in individualistic society. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 48, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuvia, A. Individualism/Collectivism and Cultures of Happiness: A Theoretical Conjecture on the Relationship between Consumption, Culture and Subjective Wellbeing at the National Level. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.; Ciarrochi, J.; Deane, F.P. Disadvantages of being an individualist in an individualistic culture: Idiocentrism, emotional competence, stress, and mental health. Aust. Psychol. 2004, 39, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R.; Dear, K. Cultural correlates of youth suicide. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 1891–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, M. The Effects of Individualistic-Collectivistic Value Orientations on Non-Fatal Suicidal Behavior and Attitudes in Turkish Adolescents and Young Adults. Scand. J. Psychol. 2013, 54, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, A.; Bliuc, A.; Molenberghs, P. The Social Contract Revisited: A re-examination of the influence individualistic and collectivistic value systems have on the psychological wellbeing of young people. J. Youth Stud. 2020, 23, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germani, A.; Delvecchio, E.; Li, J.B.; Lis, A.; Nartova-Bochaver, S.K.; Vazsonyi, A.T.; Mazzeschi, C. The link between individualism–collectivism and life satisfaction among emerging adults from four countries. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.M.; Zawadzka, A. Subjective well-being and citizenship dimensions according to individualism and collectivism beliefs among Polish adolescents. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2016, 4, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steele, L.G.; Lynch, S.M. The Pursuit of Happiness in China: Individualism, Collectivism, and Subjective Well-Being During China’s Economic and Social Transformation. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 339. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.C.; Bontempo, R.; Villareal, M.J.; Asai, M.; Lucca, N. Individualism and collectivism: Cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, H.C. Measurement of individualism-collectivism. J. Res. Personal. 1988, 22, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Luhtanen, R.K.; Cooper, M.L.; Bouvrette, A. Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 894–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Cheung, M.; Montasem, A.; International Network of Well-Being Studies. Explaining Differences in Subjective Well-Being Across 33 Nations Using Multilevel Models: Universal Personality, Cultural Relativity, and National Income. J. Personal. 2016, 84, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, E.; Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Triandis, H.C. The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Basanez, M.; Moreno, A. Human Values and Beliefs: A Cross-Cultural Sourcebook; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.; Wong, J.L.; Bagge, C.L.; Freedenthal, S.; Gutierrez, P.M.; Lozano, G. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21): Further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 68, 1322–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eskin, M. The effects of religious versus secular education on suicide ideation and suicidal attitudes in adolescents in Turkey. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogihara, Y.; Uchida, Y. Does individualism bring happiness? Negative effects of individualism on interpersonal relationships and happiness. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Krys, K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Capaldi, C.A.; Park, J.; Tilburg, W.; Osch, Y.; Haas, B.W.; Bond, M.H.; Dominguez-Espinoza, A.; Xing, C.; et al. Putting the “we” into well-being: Using collectivism-themed measures of well-being attenuates well-being’s association with individualism. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 22, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bettencourt, B.A.; Dorr, N. Collective self-esteem as a mediator of the relationship between allocentrism and subjective well-being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chew, P.Y.G.; Wilkinson, R.B. Young adults’ attachment orientations and psychological health across cultures: The moderating role of individualism and collectivism. J. Relatsh. Res. 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yetim, U. The Impacts of Individualism/Collectivism, Self-Esteem, and Feeling of Mastery on Life Satisfaction among the Turkish University Students and Academicians. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 61, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S. Goals as cornerstones of subjective well-being: Linking individuals with cultures. In Subjective Well-Being Across Cultures; Diener, E.F., Suh, E.M., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

| Lead Author (Year) | Sample Type | Ind/Coll Measure | Outcome Measure(s) | Level of Analysis | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nezlek 2021 | US: Emerging adults | Triandis 1998 | CES-D, Ryff WB (1989) | Individual | Found that individualism was negatively related to wellbeing, with this relationship varied between horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism. Both horizontal and vertical collectivism were laregly positively related to all measures of wellbeing. |

| Germani 2021 | US, Italy, Russia and China: Emerging adults | Triandis 1998 | SWLS | Individual & National | When compared across four cultures, life satisfaction was unrelated to horizontal or vertical individualism, but was positively associated with horizontal and vertical collectivism. Similarly at the individual level both dimensions of collectivism related positively to life satisfaction, while individualism was insignificant across all nations investigated. |

| Humphrey 2020 | Australia: Emerging adults | Triandis 1998 | DASS21 | Individual | Orientations towards vertical individualism predicted lower levels of psychological wellbeing, while orientations towards horizontal collectivism predicted higher psychological wellbeing. Horirontal individualism and vertical colelctivism were non-signfigant. |

| Krys 2019 | Cross Cultural: Emerging adults | Singelis 1994 | SWLS | Individual & National | Based on data collected from 12 countries, a positive association shown between life satisfaction and individualism was found when compared across cultures. These associations between individualism and wellbeing were reduced however when measured agianst modified social based items of the SWLS. |

| Lin 2017 | Australia/Singapore: Emerging Adults | Triandis 1998 | DASS21 | National | Individualism and collectivism were significantly associated with attachment avoidance but not anxiety. |

| Zalewska 2016 | Polish: Emerging Adults | Triandis 1998 | SWLS | Individual | Found a positive relationships between the horizontal and vertical dimensions of collectivism, and horizontal dimension of individualism and wellbeing, whereas vertical individualism related negatively to wellbeing. |

| Cheng 2016 | Cross-Cultrual: Emerging Adults | Hofstede 2014/Suh 1998 | SWLS | National | Individualism was not significantly linked with any components of subjective wellbeing at the national level. |

| Ogihara 2014 | US/Japan: Emerging Adults | Crocker, 2003 | SWLS | National | Individualism not associated with any negative shift in subjective wellbeing in US populations, however it is shown to associate negatively with wellbeing in a Japanese context. |

| Eskin 2013 | Turkey: Emerging Adults | Singelis 1994 | Eskin EATSS | Individual | Individualistic tendencies associated with more permissive attitudes toward suicide when compared with collectivistic tendencies. |

| Scott 2004 | Australia: Emerging adults | Triandis 1998 | BDI 1996 | Individual | Individualism associated with poorer social support, less satisfying social networks and diminished psychological wellbeing indicators. |

| Yetim 2003 | Turkey: Emerging adults | Hui 1988 | SWLS 1985 | Individual | Findings specific to the University student cohort within this participant sample revealed that individualism predicted high life satisfaction and collectivism predicted low life satisfaction in Turkish young people. |

| Eckersley 2002 | Cross-cultural: adolecsents/Emerging adults | Veenhoven 1999 | WHO Suicide data | National | Individualism associated with higher levels of wellbeing when looked at across cultures, however individualistic cultures also associated with a higher suicide rates for young people when compared to collectivistic ones. |

| Oishi 2000 | Cross-cultural: Emerging adults (College Students) | Traindis 1995 | SWLS | National | Horizontal individualism positively associated with wellbeing in the pre-identified individualistic nations (but not in the collectivistic nations), while horizontal collectivism was positively associated with wellbeing in most collectivistic nations. Vertical individualism related negatively to wellbeing in most countries investigated. |

| Bettencourt 1997 | US: Emerging Adults | Traindis 1988 | SWLS | Individual | Across 2 studies individualism was negatively correlated with wellbeing, while collectivism related positively with wellbeing. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Humphrey, A.; Bliuc, A.-M. Western Individualism and the Psychological Wellbeing of Young People: A Systematic Review of Their Associations. Youth 2022, 2, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010001

Humphrey A, Bliuc A-M. Western Individualism and the Psychological Wellbeing of Young People: A Systematic Review of Their Associations. Youth. 2022; 2(1):1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleHumphrey, Ashley, and Ana-Maria Bliuc. 2022. "Western Individualism and the Psychological Wellbeing of Young People: A Systematic Review of Their Associations" Youth 2, no. 1: 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010001

APA StyleHumphrey, A., & Bliuc, A.-M. (2022). Western Individualism and the Psychological Wellbeing of Young People: A Systematic Review of Their Associations. Youth, 2(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth2010001