An Online Collaborative Approach to Developing Ontologies to Study Questions About Behaviour

Abstract

1. Introduction

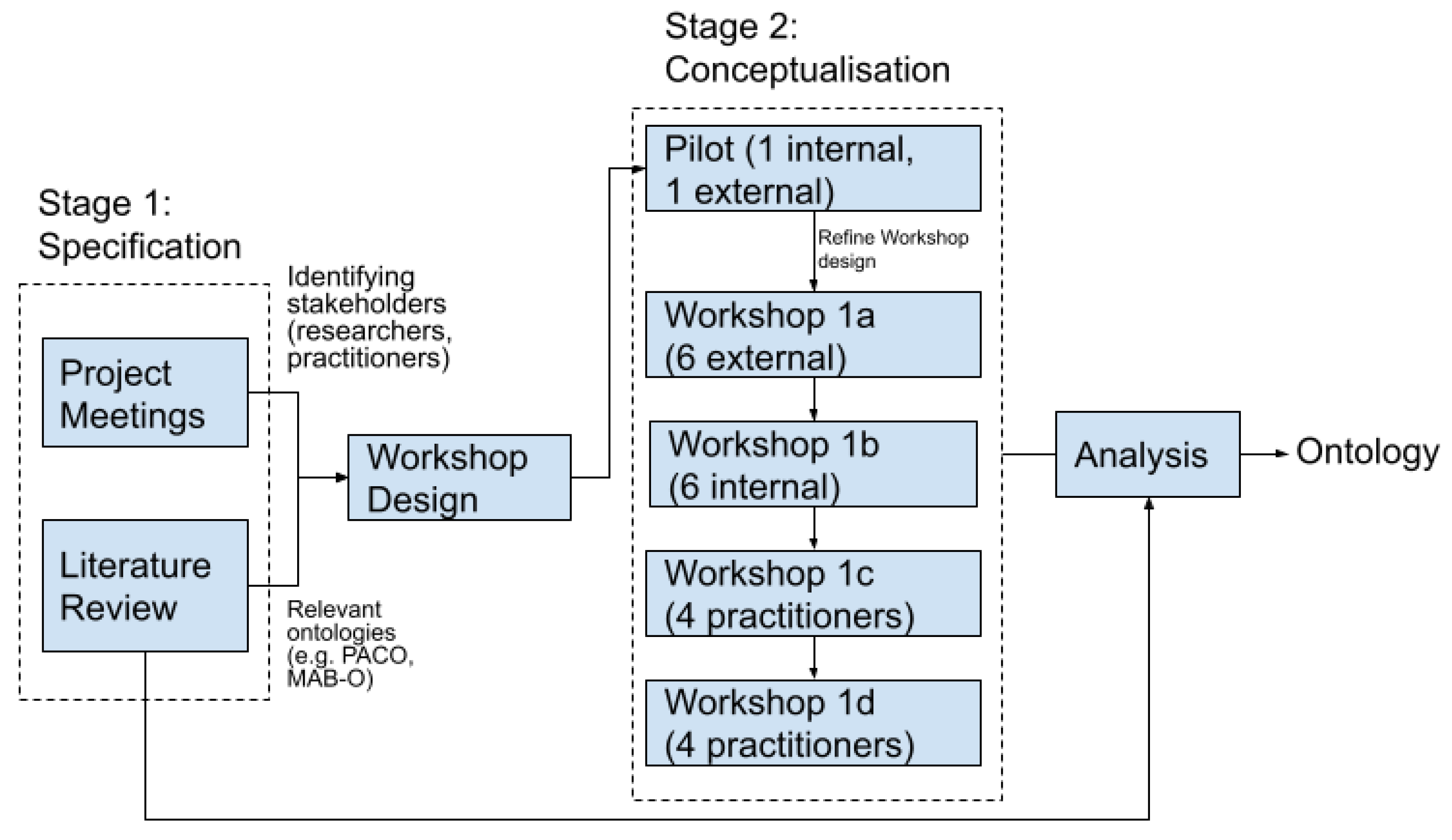

1.1. Ontologies and Ontology Design

- Specification: where the scope and requirements of the stakeholders are understood,

- Conceptualisation: where the generic abstract description of the concepts needed to represent a purpose are created [6],

- Formalisation: where the conceptual model is translated,

- Implementation: where the formal model is implemented in standard ontology language,

- Maintenance: where the ontology is evolved and evaluated into a formal model.

1.2. Novelty and Contribution

- RQ1: How do participants engage with identifying characteristics of (human) behaviour?

- RQ2: How do participants experience a “hands-on” ontology co-design process in an online setting?

- RQ3: What kind of discussions and interactions emerge when co-designing an ontology in an online setting?

- RQ4: What potential application contexts do participants envisage the ontology to support?

- 1.

- We present our approach and experiences in the specification and conceptualisation stages of co-creating an upper ontology of the characteristics of human behaviour;

- 2.

- To our knowledge, this is one of the first times that a synchronous online distributed approach has been used to support the co-design of an ontologies with domain experts;

- 3.

- Drawing from our experiences, we share practical recommendations for developing ontologies using online co-design processes.

2. Related Work

2.1. Co-Design in Ontology Development

2.2. Ontology Co-Design Approaches

2.3. Online Collaboration Tools

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Stage 1: Specification

3.1.1. Approach

- A systematic review of how existing ontologies have characterised behaviour [29];

- Identification of relevant stakeholders who could participate in a series of online workshops.

3.1.2. Identifying the Scope of the Ontology

- Researchers interested in human behaviour across a wide range of disciplines (e.g., psychologists, economists, sociologists, political scientists), for whom the ontology would help them to understand the relationships between behaviours;

- Researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers designing interventions intended to increase or reduce specific behaviours (e.g., physical activity), for whom the ontology would help to (i) identify ‘core’ behaviours (e.g., behaviours that are likely to co-occur with others and potentially influence them [33]) and (ii) estimate the possible effects of any changes on other behaviours;

- Businesses that need to understand how behaviours are related. For example, a supermarket that needs to understand whether and how behaviours like reusing coffee cups are associated with other actions, such as avoiding meat.

3.2. Step 2: Conceptualisation

3.2.1. Method

3.2.2. Participants

- Pilot—internal project researcher and external academic stakeholder (n = 2);

- Workshop 1a—external academic stakeholders (n = 6, all academics);

- Workshop 1b—internal project researchers (n = 6, all academics);

- Workshop 1c—practitioners, businesses, and charities interested in behaviour (n = 4, comprising government health agency (1), conservation (1), transport company (1), pet food company (1);

- Workshop 1d—practitioners, businesses, and charities interested in behaviour (n = 4, comprising practitioners from charity (1), local government (1), government health agency (1), academic (1)).

3.2.3. Pre-Workshop Activities

3.2.4. Facilitation

3.2.5. Materials and Activities

- Task 1: “Thinking about behaviour, what are the core (high level) concepts that are needed to describe and model it? Can you list some concepts?”

- Task 2: “Which five concepts are the most important ones?”, “How would you characterise the concepts?” (looking at the concepts everyone has listed)

- -

- “Choose some concepts and add comments with the relevant properties (i.e., name, etc.)”

- -

- “Can you connect pairs of concepts with a relation?”

- Task 3: “Imagine you had a system that uses the concepts and relationships to find relevant information from studies of behaviour. What kind of questions would you be interested in answering using such a system?”

3.2.6. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Co-Designed Ontology

- RQ1: How do participants engage with identifying characteristics of (human) behaviour?

4.2. Characteristics of Behaviour

4.3. Identifying Associated Concepts

| <Behaviour> correlatesWith <Behaviour> <Behaviour> largeCorrelation <Behaviour> <Behaviour> mediumCorrelation <Behaviour> <Behaviour> smallCorrelation <Behaviour> |

4.4. Participant Experiences

- RQ2: How do participants experience a “hands-on” ontology co-design process in an online setting?

4.4.1. Nature of Online Collaboration

- “Where should it go… I would probably leave it there.”

- “Can someone remind me what was the value exchange?”,which was followed by another participant responding with examples of value exchange, explaining how the concept links with behaviour.

4.4.2. User Experience

- “I have to say, I absolutely love this this system!… I find it mesmerising watching people move about.”

- “I like the fact that you can literally see people’s thought process by the movement of their cursor.”

- “Yeah. Exactly! I need to stop moving around while I’m thinking”

4.5. Discussions and Interactions During the Workshops

- “I don’t know if I understood what you were getting at”: trying to confirm whether the difficult concepts have been sufficiently well articulated.

- “I just needed some moral support for that” before adding the concept, confirming with other participants. In understanding how the conversations emerged during the workshops, we answer the following research question:

- RQ3: What kind of discussions and interactions emerge when co-designing an ontology in an online setting?

4.5.1. Think-Aloud Strategy

- “… it would be very useful if you could try to verbalise why you are doing specific things or what you refer to when you create specific concepts so the others may suggest and agree…”

- “So it’s really helpful if we do this a bit like a think-aloud study so we say what we are writing.”The prompts initiated a variety of conversations, most of which could be categorised as (i) announcing contributions; (ii) co-working discussions; (iii) seeking opinions; (iv) seeking clarification; or (v) inviting contributions. We identified these types of conversations by manually re-playing video recordings of the sessions and coding the different themes of the discussions using a thematic analysis approach [41]. We describe the different types of conversations together with some examples in the following subsections.

4.5.2. Announcing Contributions

- “I’m making a little cluster here of aspects that involve other people: individual vs. collective.”Participants would, additionally, also often provide some rationale for why they created a concept or positioned the concept in a specific location and why they felt that the concept was important. At times, this would also involve questioning the meaning of concepts that others had created. For example, one participant said:

- “…I moved certain concepts near to one another, i.e., habitual behaviour, frequency which is a component of whether behaviour is habitual or not. I initially thought [about] whether a behaviour is biologically driven, thinking of food- and sleep-related behaviours… and somebody else had written ‘need’. Maybe we were thinking on similar lines, perhaps a broader construct? So, I positioned them close to one another.”

- “So, I’ve got this one here: context and shifting priorities. So with that… I mean…maybe in one circumstance, my behaviour would be one thing but in another, in a different circumstance, I don’t know… I mean a different group of people, or in a different geography, my behaviour would change.” In reply to the participant raising the context of the behaviour, another participant explained how their concepts align with the broader topic of the context of the behaviour:

- “Yeah, it also links to this group here (pointing to another section of the ontology). So with compliance, personal desire, wanting to do the behaviour, that might also change with your wanting to do and the motivation of the behaviour.”

4.5.3. Discussions During Collaboration

- “Just added something about complexity, thinking about something very simple almost reflex-related behaviours vs. much more complex behaviours and how a lot of the drives might interact in different levels depending on the complexity of the behaviour.”Another participant, in response, mentioned that their contribution also aligned with the notion of complexity, albeit with a different framing:

- “I put something related to that; so, I put effortfulness, ease, and difficulty and positioned it next to the complex tag.”During the task, participants also announced how they were contributing to the co-design of the ontology. For example, in deleting or adding new concepts:

- “It’s there already. I’ll delete that.”

- “I stuck that in, and I just stuck a couple of examples in.”

4.5.4. Asking for Opinions

- “I’ve just put something on ‘behaviour is changeable’, but I’m now thinking that some behaviour is changeable in some circumstances… I’m just wondering where that might fit?…”

- “Behaviours are harder to change, aren’t they? Can we say they are completely unchangeable?”The second participant responded, linking to the effort involved in conducting a behaviour:

- “Maybe it links to the effort for (the) most bit…” The first participant, who initiated this discussion, also indicated the role of habit:

- “I think it partly relates to habit and habit formation…”

- “I’m just wondering if short term/long term cost benefits might go somewhere closer to prevention/promotion? Whether these things are positive or negative, whether we are promoting them or preventing them. So just shifted that there…”

4.5.5. Seeking Clarification

- “Who wrote that behaviours co-occur? Because I was kind of thinking the same thing.”One participant asked:

- “I was thinking about the idea of world view: who put world view in there? what did you mean by world view?”Another participant responded:

- “That was me. I guess I was trying to think about a collection of influences about how individuals see the world, that’s often influenced by values, social norms… as a broader umbrella of how we see the world-threats, opportunities…”Some participants also wanted to clarify the meaning of existing concepts before adding any new concepts. At times, requests for clarifications invited some further discussions around the topic, where participants shared why the concepts that were added were relevant, based on research or experience in practice.

4.5.6. Inviting Contributions from Others

- “I’m making a little cluster here of aspects that involve other people; so, I’ve got individual vs. collective, whether the behaviour benefits others or not, does the behavior necessarily require others. I don’t know if others have other ideas that could be added to this cluster?”

4.5.7. Participant Choices

- “…when you click ‘sticky notes’, you get to choose the colour. I noticed that people are creating notes of different colours. I wonder if there is any purpose to their colours?”

- “not for me, (team member name)—I used yellow because I am familiar with yellow post-it notes.”Another participant (jokingly) added: “I think you are giving us too much credit”.A third participant added that their choice of colour was to differentiate their contribution from others: “The blue one’s just me.”

- “So just thinking, where we’ve got the purply blue colour vs. our pink colour, I feel like … I don’t know there is a distinction between them that I am not going to be able to articulate, but I think for me…maybe the determinants is almost like we’ve got high level determinants like the environment and then we have the proximally distal ones which then map to some of the pink ones…so we could look at the determinants that way? Would others be okay with that?”

4.6. Potential Applications

- RQ4: What potential application contexts do participants envisage the ontology to support?

5. Discussion

5.1. Recommendations for Using Online Tools to Support Ontology Co-Design

5.1.1. The Value of Pre-Recording

5.1.2. Recording Workshop Sessions

5.1.3. The Value of Note-Taking

5.1.4. Multiple Facilitators with Dedicated Roles

5.1.5. Length of Workshops and Importance of Pilot

5.1.6. Participant Numbers and Stakeholder Groups

5.2. Future Directions and Applications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Webb, T.; Baird, H.; Maikore, F.; West, R.; Hastings, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Lanfranchi, V.; Michie, S. A method for evaluating the interoperability of ontology classes in the behavioural and social sciences. Wellcome Open Res. 2025, submitted. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pérez, A.; Fernández-López, M.; Corcho, O. Ontological Engineering: With Examples from the Areas of Knowledge Management, e-Commerce and the Semantic Web; Springer London: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bechhofer, S.; Van Harmelen, F.; Hendler, J.; Horrocks, I.; McGuinness, D.L.; Patel-Schneider, P.F.; Stein, L.A. OWL web ontology language reference. W3C Recomm. 2004, 10, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bleumers, L.; Jacobs, A.; Sulmon, N.; Verstraete, M.; Van Gils, M.; Ongenae, F.; Ackaert, A.; De Zutter, S. Towards ontology co-creation in institutionalized care settings. In Proceedings of the 2011 5th International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare (PervasiveHealth) and Workshops, Dublin, Ireland, 23–26 May 2011; pp. 559–562. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, H.S.; Martins, J.P. Ontologies: How can they be built? Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2004, 6, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genesereth, M.R.; Nilsson, N.J. Logical Foundations of Artificial Intelligence; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, VT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, D.; Namioka, A. Participatory Design: Principles and Practices; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ongenae, F.; Bleumers, L.; Sulmon, N.; Verstraete, M.; Van Gils, M.; Jacobs, A.; De Zutter, S.; Verhoeve, P.; Ackaert, A. Participatory design of a continuous care ontology-towards a user-driven ontology engineering methodology. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development, Paris, France, 26–29 October 2011; pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, E.; Hastings, J.; Marques, M.M.; Mutlu, A.N.F.; Zink, S.; Michie, S. Why and how to engage expert stakeholders in ontology development: Insights from social and behavioural sciences. J. Biomed. Semant. 2021, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongenae, F.; Duysburgh, P.; Sulmon, N.; Verstraete, M.; Bleumers, L.; De Zutter, S.; Verstichel, S.; Ackaert, A.; Jacobs, A.; De Turck, F. An ontology co-design method for the co-creation of a continuous care ontology. Appl. Ontol. 2014, 9, 27–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuziemsky, C.E.; Lau, F. A four stage approach for ontology-based health information system design. Artif. Intell. Med. 2010, 50, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hocker, J.; Schindler, C.; Rittberger, M. Participatory design for ontologies: A case study of an open science ontology for qualitative coding schemas. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 72, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehndorf, R. What is an upper level ontology? Ontogenesis. 2010. Available online: https://research.aber.ac.uk/en/publications/what-is-an-upper-level-ontology/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Schenk, P.M.; West, R.; Castro, O.; Hayes, E.; Hastings, J.; Johnston, M.; Marques, M.M.; Corker, E.; Wright, A.J.; Stuart, G.; et al. An ontological framework for organising and describing behaviours: The human behaviour ontology. Wellcome Open Res. 2024, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; West, R.; Finnerty, A.N.; Norris, E.; Wright, A.J.; Marques, M.M.; Johnston, M.; Kelly, M.P.; Thomas, J.; Hastings, J. Representation of behaviour change interventions and their evaluation: Development of the Upper Level of the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 5, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, N.; Paul, C.; Turon, H.; Oldmeadow, C. Which modifiable health risk behaviours are related? A systematic review of the clustering of Smoking, Nutrition, Alcohol and Physical activity (‘SNAP’) health risk factors. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simperl, E.; Mochol, M.; Bürger, T. Achieving maturity: The state of practice in ontology engineering in 2009. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2010, 7, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, G.; Druin, A.; Guha, M.L.; Bonsignore, E.; Foss, E.; Yip, J.C.; Golub, E.; Clegg, T.; Brown, Q.; Brewer, R.; et al. DisCo: A co-design online tool for asynchronous distributed child and adult design partners. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Bremen, Germany, 12–15 June 2012; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.A.; Weistroffer, H.R. A new look at the relationship between user involvement in systems development and system success. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2009, 24, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemman, M.; Kleppe, M. User required? on the value of user research in the digital humanities. In Proceedings of the CLARIN 2014 Conference, Soesterberg, The Netherlands, 24–25 October 2014; number 116. pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C. Studying users in digital humanities. Digit. Humanit. Pract. 2012, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsun, M.; Myers, T.; Hardy, D. C-DOM: A structured co-design framework methodology for ontology design and development. In Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Science Week Multiconference, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 29 January–2 February 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Horton, J.J.; Ozimek, A.; Rock, D.; Sharma, G.; TuYe, H.Y. COVID-19 and Remote Work: An Early Look at US Data; Technical Report; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold, B.K. Beyond zoom: The new reality. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, B.K. Connecting through technology during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Avoiding “Zoom Fatigue”. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudorache, T.; Vendetti, J.; Noy, N.F. Web-Protege: A Lightweight OWL Ontology Editor for the Web. In Proceedings of the OWLED, Washington, DC, USA, 1–2 April 2008; Volume 432, p. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann, S.; Negru, S.; Haag, F.; Ertl, T. Visualizing ontologies with VOWL. Semantic Web 2016, 7, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Figueroa, M.C.; Gómez-Pérez, A.; Villazón-Terrazas, B. How to write and use the ontology requirements specification document. In Proceedings of the OTM Confederated International Conferences “On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems”, Vilamoura, Portugal, 1–6 November 2009; pp. 966–982. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, H.; Norman, P.; Webb, T.; Huddy, V.; Scott, A.; Rowe, R.; Sabiu Maikore, F.; Mazumdar, S.; Lanfranchi, V.; Ciravegna, F. A systematic review of how existing ontologies characterise behaviour. Paper presented at the 36th Conference of the European Health Psychology Society, Bratislava, Slovakia, 23–27 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, K.R.; Ramsay, L.J.; Godinho, C.A.; Gershuny, V.; Hovorka, D.S. IC-Behavior: An interdisciplinary taxonomy of behaviors. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachan, R.R.; Lawton, R.J.; Conner, M. Classifying health-related behaviours: Exploring similarities and differences amongst behaviours. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.O.; Heron, T.E.; Heward, W.L. Applied Behavior Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman, G.; Kalish, Y.; Shiloh, S. The centrality of health behaviours: A network analytic approach. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Beck, M.; Bryman, A.E.; Liao, T.F. The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelan, S.A. Group size, group development, and group productivity. Small Group Res. 2009, 40, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, N.F.; McGuinness, D.L. Ontology Development 101: A Guide to Creating Your First Ontology; Stanford Knowledge Systems Laboratory: Stanford, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Charters, E. The use of think-aloud methods in qualitative research an introduction to think-aloud methods. Brock Educ. J. 2003, 12, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madill, A.; Jordan, A.; Shirley, C. Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. Br. J. Psychol. 2000, 91, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 2, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, D.; Gosling, A.; Weinman, J.; Marteau, T. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology 1997, 31, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ariss, T.; Caumiant, E.P.; Fairbairn, C.E.; Kang, D.; Bosch, N.; Morris, J.K. Exploring associations between drinking contexts and alcohol consumption: An analysis of photographs. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2025, 134, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerinen, A.; Tauber, R. Ontology development by domain experts (without using the “O” word). Appl. Ontol. 2017, 12, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, M.; Constabaris, A.; Brickley, D. Foaf: Connecting people on the semantic web. Cat. Classif. Q. 2007, 43, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijgersberg, H.; Van Assem, M.; Top, J. Ontology of units of measure and related concepts. Semantic Web 2013, 4, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, M.H.; Shefchek, K.A.; Haendel, M.A. SEPIO: A Semantic Model for the Integration and Analysis of Scientific Evidence. In Proceedings of the ICBO/BioCreative, Corvallis, OR, USA, 1–4 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, J.R.; Pan, F. Time ontology in OWL. W3C Work. Draft. 2006, 27, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar, S.; Maikore, F.; Lanfranchi, V.; Roychowdhury, S.; Webber, R.; Baird, H.M.; Basir, M.; Huddy, V.; Norman, P.; Rowe, R.; et al. Understanding the relationship between behaviours using semantic technologies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28 July 2023; pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers, M.W.; Steen, T.; Van Den Bos, C.; Geenen, M. The think aloud method: A guide to user interface design. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2004, 73, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadzie, A.S.; Bhagdev, R.; Chakravarthy, A.; Chapman, S.; Iria, J.; Lanfranchi, V.; Magalhães, J.; Petrelli, D.; Ciravegna, F. Applying semantic web technologies to knowledge sharing in aerospace engineering. J. Intell. Manuf. 2009, 20, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.; Zhang, L.; Schenk, P.; West, R.; Gehrke, B.; Hogan, W.R.; Chorpita, B.; Johnston, M.; Marques, M.M.; Webb, T.L.; et al. The BSSO Foundry: A community of practice for ontologies in the behavioural and social sciences. Wellcome Open Res. 2024, 9, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.; Brown, J.; Shahab, L.; Baird, H.; Webb, T.; Squires, H.; Tattan-Birch, H.; Gillespie, D.; Purshouse, R.; Brennan, A.; et al. Annotating datasets in behavioural and social sciences to promote interoperability: Development of the Schema for Ontology-based Dataset Annotation (SODA) version 1.0. Wellcome Open Res. 2025, 10, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Workshop and Composition | Concepts Contributed |

|---|---|

| Pilot | |

| Internal and external (n = 2) | Characteristics of behaviour, material, goals, participants, temporality |

| Workshop 1a External academic stakeholders | |

| (n = 6) | Characteristics of behaviour, material, goals, participants, temporality, needs and emotions, norms, beliefs, impact and consequence |

| Workshop 1b | |

| Internal project researchers (n = 6) | Characteristics of behaviour, participants, temporality |

| Workshop 1c | |

| Practitioners, businesses, and charities interested in behaviour (n = 4) | Goals, context of behaviour, needs and emotions, norms, belief, impact and consequences, motivations and determinants |

| Workshop 1d | |

| Practitioners, businesses, and charities interested in behaviour (n = 4) | Material, goals, needs and emotions, norms, belief, motivations and determinants |

| Metrics | Upper Level | FOAF | OM | SEPIO | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axiom | 651 | 70 | 24 | 163 | 88 |

| Logical axiom count | 170 | 15 | 3 | 12 | 12 |

| Declaration axioms count | 168 | 13 | 6 | 28 | 15 |

| Class count | 73 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 6 |

| Object property count | 43 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Data property count | 25 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Individual count | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Annotation property count | 31 | 4 | 3 | 14 | 6 |

| Class axioms | |||||

| SubClassOf | 46 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 4 |

| EquivalentClasses | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DisjointClasses | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Object property axioms | |||||

| SubObjectPropertyOf | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| ObjectPropertyDomain | 41 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| ObjectPropertyRange | 39 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| SubPropertyChainOf | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Data property axioms | |||||

| SubDataPropertyOf | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FunctionalDataProperty | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DataPropertyDomain | 18 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| DataPropertyRange | 20 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Annotation axioms | |||||

| AnnotationAssertion | 297 | 42 | 15 | 123 | 61 |

| AnnotationPropertyDomain | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AnnotationPropertyRangeOf | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Competency Question | Candidate Answer |

|---|---|

| What is the name of the study that measured/observed this behaviour? | Name of the study |

| What is the sample size of the study that is used to measure this behaviour? | Sample size values |

| Given a behaviour, what is the name of a correlated behaviour and the correlation coefficient? | Name of the correlated behaviour (e.g., recycling, sleeping), a value of r (e.g., 0.1, 0.5) |

| Where does ’this behaviour’ occur (location)? | At home, at work, at the park, etc. |

| If this behaviour requires the use of materials, what are the materials? | Car, Walking stick |

| What is the weighted correlation between two behaviours that are measured in more than one study? | A calculated weighted correlation (Pearson, Spearman, etc.) |

| What is the association between two behaviours that have not been measured/compared in the same study | The relationship represented as the list of behaviours that link the two behaviours |

| Is this behaviour legal? | Yes, No, Unsure |

| Behaviour A | Correlation_r | Behaviour B |

|---|---|---|

| Moving/Exercising | 0.19 | Eating Vegetables |

| Moving/Exercising | 0.01 | Smoking Cigar(ette) |

| Moving/Exercising | 0.69 | Using Alcohol |

| Moving/Exercising | 0.11 | Using Alcohol |

| Moving/Exercising | 0.16 | Smoking Marijuana |

| Moving/Exercising | 0.125 | Smoking Cigar(ette) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazumdar, S.; Maikore, F.; Lanfranchi, V.; Baird, H.; Ciravegna, F.; Huddy, V.; Norman, P.; Rowe, R.; Scott, A.J.; Webb, T.L. An Online Collaborative Approach to Developing Ontologies to Study Questions About Behaviour. Knowledge 2025, 5, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge5040026

Mazumdar S, Maikore F, Lanfranchi V, Baird H, Ciravegna F, Huddy V, Norman P, Rowe R, Scott AJ, Webb TL. An Online Collaborative Approach to Developing Ontologies to Study Questions About Behaviour. Knowledge. 2025; 5(4):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge5040026

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazumdar, Suvodeep, Fatima Maikore, Vitaveska Lanfranchi, Harriet Baird, Fabio Ciravegna, Vyv Huddy, Paul Norman, Richard Rowe, Alexander J. Scott, and Thomas L. Webb. 2025. "An Online Collaborative Approach to Developing Ontologies to Study Questions About Behaviour" Knowledge 5, no. 4: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge5040026

APA StyleMazumdar, S., Maikore, F., Lanfranchi, V., Baird, H., Ciravegna, F., Huddy, V., Norman, P., Rowe, R., Scott, A. J., & Webb, T. L. (2025). An Online Collaborative Approach to Developing Ontologies to Study Questions About Behaviour. Knowledge, 5(4), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge5040026