1. Introduction

The concept of ‘

competency’ is sensitive and muti-dimensional. It encompasses a wide range of potentials, abilities, skills, and knowledge that individuals possess [

1,

2,

3]. Competency empowers individuals to perform various tasks effectively across different domains and contexts [

4]. Emphasising that it is not a one-size-fits-all (and, in fact, not a unique and constant) concept, scholars and organisations acknowledge the complexity of competency. Understanding the nuances of competency is key to unlocking the full potential of both individuals and organisations, especially when the central focus comprises knowledge and knowledge development. In this article, we will conceptually deal with how the interconnections between individual competencies and organisational goals can drive knowledge in modern organisations.

1.1. Literature Review Methodology

To ground our exploration of competency mapping as a driver of knowledge in contemporary organisations, we report that we, in this paper, have undertaken a dynamic investigation into relevant scholarly work. Our main goal was to interconnect a wide range of perspectives. Since we wanted to understand how individual strengths could contribute to collective objectives, we engaged with diverse sources across organisational theory and knowledge creation.

Rather than adhering to a strict methodology, our approach was shaped by a genuine curiosity to uncover insights that reflect the dynamic and multi-dimensional nature of today’s workplaces. We examined how competencies operate across different settings—ranging from formal educational environments to fast-paced organisational contexts—with a focus on their potential to promote innovation and adaptability. This involved exploring narratives that illustrate how skills and intelligence intersect to support organisational growth, while also acknowledging the personal and relational aspects of knowledge work. Through this integrative process, we developed a conceptual base for our word exploration, and here, we attempt to present the intriguing concept of ‘competency mapping’ to readers as a strategic tool for building knowledge-centred organisations, where human talent aligns with broader visions for success.

Our literature review drew on a diverse set of scholarly works, including academic articles, books, and industry reports, spanning from foundational studies to recent publications. We prioritised sources that explored competency mapping, knowledge management, intelligence quotients, and organisational strategy, selecting those that addressed how individual and collective skills drive innovation, flexibility, and adaptability. This selection process involved reviewing works in fields such as organisational behaviour, business psychology, human resource management, strategic management, and emotional intelligence to ensure a comprehensive synthesis that supports our theoretical framework. By integrating these perspectives, we aimed to provide a robust foundation for understanding competency mapping as a tool for knowledge-driven organisations.

To clarify the foundation of our competency mapping framework, we outline its key constructs and their basis in the literature. Cognitive competencies, encompassing abilities for problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making, are informed by studies exploring analytical skills and their role in strategic decision-making within organisations (with their internal and external stakeholders). Technical competencies, which include job-specific skills such as proficiency in tools or software, draw on works in the literature examining technical expertise and its impact on organisational innovation. Interpersonal competencies, covering skills for communication, interaction, and teamwork, are grounded in research on collaboration and conflict resolution in workplace settings. Intrapersonal competencies, involving self-awareness and personal emotional regulation, are derived from works on emotional intelligence and adaptability in dynamic environments in business and academic settings. This synthesis of the literature across these constructs supports our theoretical framework, demonstrating how competency mapping drives knowledge development in organisations.

1.2. Scope and Contribution of the Study

This paper is a theoretical exploration that advances knowledge management by proposing a framework for competency mapping to align individual capabilities with organisational goals to develop knowledge-driven workplaces. It synthesises perspectives from organisational theory, emotional intelligence, and strategic management to offer practical insights for modern organisations. By integrating cognitive, technical, emotional, interpersonal, and intrapersonal competencies in line with organisational values and strategies, mission, and vision, the framework emphasises emotional and cultural factors in knowledge creation, shaping, and sharing. This contributes to the journal’s focus on innovative knowledge management approaches, particularly in technology-driven and globalised settings, by providing a structured model to transform individual potential into collective organisational success.

2. Competency Across Contexts

Competency is a very wide notion encompassing various aspects that must be viewed from different angles. For this, the way we view ‘competency’ needs to be flexible and adapted to the context in which it is applied (i.e., become contextualised) [

5], since the operational context and the intermingled situational consequences can have a great influence on our diverse competency levels.

In an educational setting, competency may refer to the level of knowledge and skills that students possess to meet the learning objectives of their courses. Here, competency can be evaluated through exams, assignments, tasks, homework, performance in class discussions, and other formative/summative assessments that measure students’ ability to apply their knowledge to solve problems and make efficient decisions. Moreover, in educational settings, when transmitting knowledge to the students, educators, as well as considering the competencies of students, should also focus on their learning types, namely, (i) auditory, (ii) visual, (iii) haptic, (iv) kinaesthetic, etc. Usually, a combination of these approaches in an educational setting can greatly stimulate the knowledge acquisition of students, making the task of educators easier and more efficient. We strongly believe that it is the task of each and every educator to reveal the potential and learning types of their students, to generate successful outputs and eventual good results.

In a workplace setting, competency is often viewed as a combination of technical skills, interpersonal skills, and work-related knowledge that employees possess to perform their job duties/functions effectively [

2,

6,

7]. Employers may assess employees’ competency through job interviews, practical tests, interval and resultant performance evaluations, and training programmes to ensure that they have the necessary skills and knowledge to meet the organisation’s goals. So, in various organisational settings, it can be interpreted that some competency is defined and analysed based on (i) contextual analysis of organisations, as well as the identification of their overall (quantitative and qualitative) goals, (ii) conceptual and logical analysis of how individuals’ skills and knowledge are interrelated to the organisations’ goals, and (iii) the DEIB (namely, diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) approach of a certain company, which adds immense value to the shaping of a new set of skills adhering to the protection of human rights, protecting human psychological well-being and equality for all parties involved.

It is also worth mentioning here that competency can also be viewed from a broader perspective (that can still be in line with our analysis of organisations). Here, competency encompasses any individual’s ability to navigate and adapt to their complex and rapidly changing world. In this case, competency may include skills such as decision-making, problem-solving, adaptability, flexibility, digital literacy development, critical thinking, emotional intelligence, creativity, invention, innovation, and technology development [

8]. These skills are essential for individuals to thrive in a world that is constantly developing, where innovation and social and digital transformation are happening faster than ever before.

At this point, to fully appreciate the role of competencies in modern organisations, we must establish a clear taxonomy, as this forms the foundation for aligning individual capabilities with organisational goals. Competencies can be broadly classified into four categories: (i) cognitive, (ii) technical, (iii) interpersonal, and (iv) intrapersonal, each contributing uniquely to knowledge development, cognitive and psychological fitness and resultant organisational success.

Cognitive Competencies: These encompass abilities related to problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making. For example, a marketing analyst leveraging data to identify consumer trends demonstrates cognitive competency, enabling strategic decision-making aligned with organisational objectives.

Technical Competencies: These refer to job-specific skills and knowledge, such as proficiency in tools, software, or machinery. An engineer skilled in CAD software to design innovative products exemplifies technical competency, directly supporting organisational innovation goals.

Interpersonal Competencies: These involve skills for effective interaction, including communication, teamwork, engagement, collaboration, psychological and mental well-being, and conflict resolution. A project manager facilitating cross-departmental collaboration to meet deadlines showcases interpersonal competency, fostering a cohesive work environment, where everything is aligned with the company’s needs and values.

Intrapersonal Competencies: These include self-awareness, self-management, emotional regulation, social awareness, flexibility and adaptability. An employee managing stress well to maintain productivity under tight deadlines demonstrates a high level of intrapersonal competency, contributing to personal and organisational resilience and meeting targets.

In a nutshell, all the aforementioned competencies are of high importance in building a strong arsenal of skills that can greatly stimulate professional growth and aid in meeting educational and/or company goals and ensuring a bright future.

3. Aligning Competency with Organisational Values

An organisation’s values are the guiding principles that shape its culture, behaviours, decisions, and actions [

7,

9,

10]. These values define what the organisation, quantitatively and qualitatively, stands for and what its leaders aim for. An organisation’s values also influence how it interacts with the environment (in particular, with customers, consumers, partners, external stakeholders, and competitors); see [

8].

The specific values that any organisation adopts depend on its mission, vision, and strategic objectives, as well as its company culture, history, values, and leadership styles.

An organisation’s ‘mission’ is, in fact, a statement that defines and describes its purpose, target, scope and core values. A mission explains (i) why the organisation exists, (ii) what the organisation does, (iii) who the organisation serves, and (iv) what the core values of the organisation are. Also, an organisation’s ‘vision’ provides a long-term perspective on (i) what the organisation wants to achieve by means of setting short-term and long-term goals and (ii) where the organisation wants to be in the shorter and longer run.

Generally, it is very important for any organisation to have a crystal-clear mission and vision that will be part and parcel of their strategy so that they can lead the entire team towards success by following clear guidelines, since, with the help of these, a corporation can navigate times of adversities and challenges.

Importantly, values are closely related to human competency in organisations. They provide a framework for employees to understand and apply their skills, knowledge, actions, and verbal and non-verbal communicative behaviours [

11] in alignment with the organisation’s expectations, beliefs, and strategic goals. For instance, if an organisation values teamwork, collectivism, and group-based activities, it will seek to recruit and develop employees who have strong interpersonal skills, collaboration skills, and conflict resolution skills. Likewise, if an organisation values innovation, it will encourage employees to experiment, take risks, creatively innovate, and learn from their failures, since failure is the first step towards success.

Also, if the organisation acknowledges and values the emotions and feelings of its employees, as well as their aspirations and intentions, motivations and desires, emotions and feelings, paying closer attention to the so-called ‘soft skills’ (alongside hard technical skills), which are increasingly being referred to as ‘human skills’, since AI technologies are currently acquiring these very soft skills to cooperate more efficiently and smoothly with their human counterparts, companies can eventually thrive in any sector of human activity, since the human ability to deal with one’s very own emotions and the emotions of others adds to the so-called ‘emotional capital’ of the company [

12,

13]. It is also highly important to mention here that the emotional capital includes the level of one’s ability to deal not only with one’s own emotions but also with the emotions of others. Moreover, our ability to build long-lasting fruitful relations with our colleagues, co-workers, business partners, customers, students, stakeholders, and clients is of great importance in enhancing the emotional capital of an organisation.

As we can see from

Table 1, all the aforementioned

intrapersonal (within a person) and

interpersonal (between two or more people) competencies can form a proper basis for a strong socio-economic capital in a company where one’s own emotions and those of others are also taken into account when carrying out business, representing a solid basis for efficient cooperation and strong decision-making that ensures better turnover in the business sphere.

Thus, we can assume that alongside important factors such as human capital and financial capital, emotional capital and socio-economic capital too can represent a great asset for a company in terms of sustainable success and flourishing.

All of the aforementioned skills represent a great value for the smooth and efficient operations of a company, where all the parties involved feel themselves seen and heard, highly valued, acknowledge, and cherished: this will eventually stimulate the overall success of the company that will in its turn be very beneficial for the flourishing of the society at large, where all the group members hugely invest not only in the generation of the business ventures, but also leverage eventual success by means of maintaining strong interpersonal community interrelations and an adequate level of self care.

4. Aligning Competency with Strategic Goals

An organisation’s

strategic goals are specific measurable targets that define what the organisation wants to achieve within a certain timeframe [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Strategic goals help organisations direct their efforts, prioritise their resources, and monitor their progress towards achieving their mission and vision. Strategic goals could be interpreted as dynamic functions transforming missions into visions. Correspondingly, considering the various categories and types of missions and visions, leaders and employees may make different strategic decisions to achieve their targets and values. So, in the context of competency analysis, some scholars believe that an organisation’s strategic goals are closely linked to the competencies of its employees [

5,

20]. Thus, there is no doubt that organisations need individuals with the potentials, skills, knowledge, and behaviours essential in the attainment of these specific goals.

For example, if an organisation’s strategic goal is to increase sales revenue by 20% within the next year, it will require and recruit employees who are competent in marketing, sales, customer service, generating leads, and data analysis (and who, in fact, have proper knowledge in these domains). In this case, we can deduce that the company is a market- and sales-driven one and that these employees need the ability to identify target markets, craft compelling marketing campaigns, close deals, provide exceptional customer service, and leverage data to optimise sales efforts. As another example, if an organisation’s strategic goal is to develop and launch a new product within 6 months, it will need employees with extensive knowledge in market research and development, product design, production, and project management. These individuals must possess the expertise to identify market demands, leverage innovative technologies, and coordinate cross-functional multinational teams to ensure timely and successful delivery for a goal-driven company. Additionally, their understanding of regulatory compliance and quality assurance processes will play a critical role in achieving this goal. Similarly, as another example, if an organisation aims to reduce its carbon footprint by 30% over the next five years, it will require employees who are well-versed in environmental science, renewable energy solutions, and sustainability practices when sustainability is one of the most important values of the company and meeting the SDGs (the Sustainability Development Goals) is of crucial importance. These employees should be capable of implementing energy-efficient processes, conducting comprehensive carbon audits, and developing eco-friendly products. Furthermore, their ability to educate and inspire others within the organisation about sustainable practices will be instrumental in achieving this strategic objective. All in all, in any case, we can conclude by stating that the top C-suite-level management should set clear goals and have a clear-cut idea of what essential criteria should be met, to detect competent talent and recruit accordingly.

5. Competency Mapping: A Strategic Tool in Knowledge Development

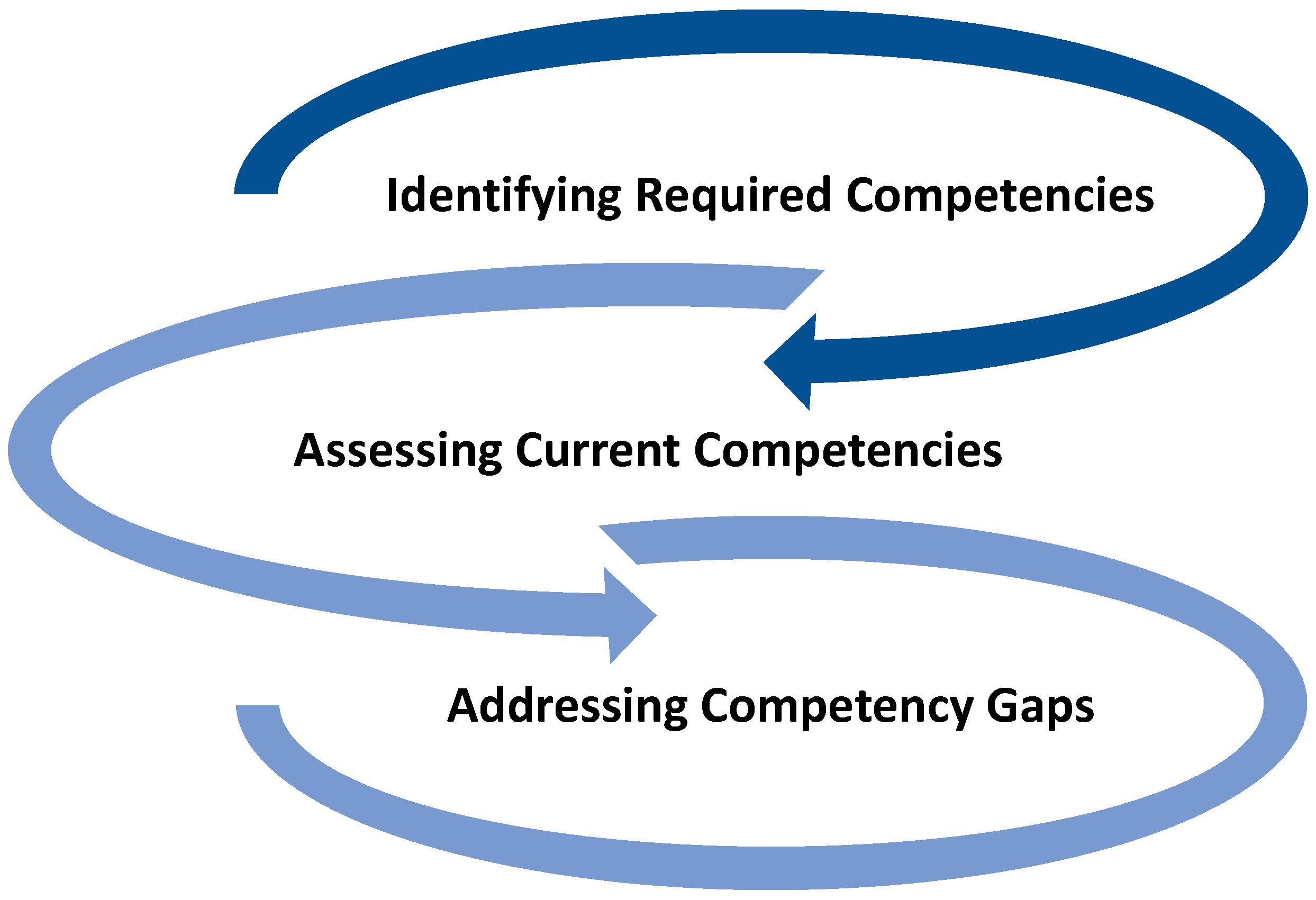

Competency mapping bridges the gap between organisational goals and individual knowledge and capabilities. It allows organisations to ensure that their workforce possesses the necessary knowledge to execute strategic objectives. As you can see in

Figure 1, this process involves three key steps:

The first functional role is to

identify the required competencies. Organisations must initially determine the specific knowledge and skill-sets essential in achieving each strategic objective. This involves a detailed breakdown of (1)

Factual Knowledge (understanding foundational informative data [

21] and domain-specific concepts); (2)

Technical Knowledge (proficiency in using tools, software, or machinery related to job functions); (3)

Interhuman Knowledge (the mastery of communication, teamwork, cooperation, and leadership abilities); (4)

Technical Skills (the integration of knowledge and techniques for effective task execution); (5)

Problem-Solving Abilities (analytical thinking and creativity for addressing challenges); (6)

Intrapersonal Skills (these involve the social-awareness and relationship management of a person), and (7)

Interpersonal Skills (these involve the self-awareness and self-regulation of a person). All of these can stimulate the overall success of a company.

For instance, in a survey conducted by [

22], 74% of executives highlighted the importance of aligning workforce competencies with long-term strategic goals. This step is typically supported by job analysis tools, industry benchmarks, and competency frameworks such as the SHRM Competency Model (see [

23]) or UNESCO’s Competency Development Framework (see [

24]). Such models provide a structured approach to defining competencies at different levels in an organisation.

The second functional role is a comprehensive assessment of the current competencies of all employees. This process aims to identify the gap between the current state and the desired competency level. Methods commonly employed here include the following:

Performance Evaluations: The assessment of employees’ practical application of their knowledge. For example, a performance metric might involve evaluating an employee’s ability to meet project deadlines with accuracy, which is quantified using Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

Skills Assessments:

Evaluation of task-specific abilities often scored using standardised tests or practical simulations. According to [

25], 42% of companies use digital tools and AI-powered platforms to evaluate employee skills.

Behavioural Interviewing: Behavioural interviewing is a technique that assesses a candidate’s ability to meet the job requirements based on their previous and current experience. This technique is based on the idea that past performance and current emotional and psychological state are the best indicators of future performance.

Self-Reported Data: Surveys and self-assessments provide insight into employees’ perceptions of their own skills and abilities. Combining self-assessments with peer reviews or manager feedback often improves reliability.

Statistical tools, such as ‘360-degree feedback analysis’ or ‘gap analysis matrices’ (see [

26,

27]), can be utilised to visualise and interpret the difference and imbalance between existing and required competencies across teams or departments. For example, a gap analysis at an IT firm revealed that 63% of employees lacked proficiency in cloud computing technologies (that was a critical skill for the organisation’s future strategy).

The third functional role is addressing competency gaps. Based on the assessment findings, organisations can design targeted interventions to bridge these gaps. This involves the following:

Designing Tailored Training Programmes: Drawing upon the theory of adult learning (in [

28]), programmes can incorporate experiential learning, e-learning modules, and hands-on workshops to cater for diverse learning styles. A meta-analysis in [

29] found that tailored training programmes improve knowledge retention by 23% compared to generic training.

Upskilling and Reskilling Initiatives: These are particularly relevant in industries experiencing rapid technological changes. For example, companies like Amazon have committed USD 700 million to upskill 100,000 employees by 2025.

Continuous Monitoring and Feedback Mechanisms: Post-training evaluations and periodic reviews help in assessing whether interventions are effectively addressing the gaps identified. Data from [

30] showed that companies with robust feedback mechanisms were 30% more likely to meet their upskilling goals.

Competency mapping is not just a static exercise; it is a dynamic and iterative process that ensures ongoing alignment between individual capabilities and organisational goals. Regular reviews of competency frameworks and periodic reassessments of the workforce are critical in adapting to changing business environments. For example, organisations implementing agile competency mapping have reported a 15–20% increase in operational efficiency; see [

31]. By leveraging competency mapping as a strategic tool, organisations can not only enhance knowledge development but also build a resilient and future-ready workforce. Through the systematic identification, assessment, and bridging of competency gaps, businesses can position themselves to achieve sustainable growth and competitive advantages.

6. Performance Measurement and Recognition

Strategic performance metrics and reward systems play a critical role in incentivising and recognising the development and application of competencies that drive both organisational and broader strategic goals. By integrating these metrics into a cohesive competency framework, organisations can align individual efforts (of course, based on individuals’ knowledge, skills, and abilities) with collective objectives, developing a culture of accountability, responsibility, dedication, innovation, as well as continuous development and improvement.

6.1. Aligning Performance Metrics with Strategic Objectives

Effective performance measurement begins with the establishment of clear, (quantitatively) measurable objectives that align closely with an organisation’s strategic goals. In the context of competency mapping, these objectives should reflect both functional competencies (specific to roles, duties and/or tasks) and core competencies (shared organisational capabilities). This alignment enables employees to understand how their individual contributions—rooted in their unique knowledge, skills, competencies, and abilities—directly impact organisational success.

For example, Kaplan and Norton’s Balanced Scorecard framework ([

32]) can be used as a tool to align performance metrics across four perspectives: (i) financial, (ii) customer, (iii) internal processes, and (iv) learning and growth. Each perspective can incorporate competency-based metrics, such as learning and growth perspectives and customer perspectives. By aligning these metrics, employees can gain clarity on how their work contributes to the organisation’s overarching goals and, accordingly, make sense of individual-based overall purpose and direction.

To illustrate the alignment of performance metrics with competencies, we draw on the Balanced Scorecard framework [

32], which integrates metrics across financial, customer, and internal processes and learning and growth perspectives. This approach ensures that individual efforts, rooted in specific competencies, contribute meaningfully to organisational goals. For example, an organisation that aims to enhance customer satisfaction by 10% might measure an employee’s ability to resolve customer complaints within 24 h. This metric reflects interpersonal competencies, such as empathy, effective communication, and cooperation, that aid in developing stronger customer relationships and driving knowledge-sharing within teams. Similarly, to meet the strategic goal of launching a new product within 6 months, an organisation could track the timely completion of design iterations. This metric assesses technical competencies in product design, ensuring that employees’ expertise translates into innovative outcomes. In the context of learning and growth, an organisation might evaluate the proportion of employees who complete training in AI tools. Such a metric highlights cognitive competencies, like learning agility, and brain plasticity, that can enable employees to adapt to technological advancements and contribute to a culture of continuous improvement. These examples truly demonstrate how competency-based metrics can create a bridge between individual capabilities and strategic objectives, nurturing knowledge-driven environments, skills, and innovation.

6.2. Recognising Competency-Driven Success

Recognition programmes should be designed to reward not just outcomes but also the underlying competencies of individuals that enable success. This approach not only reinforces desired behaviours but also promotes the continuous development of critical skills. For instance, an employee who leverages advanced analytical skills to optimise supply chain operations might receive a performance-based bonus, or a team that collaborates effectively to develop a new knowledge-sharing platform could be acknowledged through a formal award or public recognition. In knowledge-driven environments, organisations can establish mechanisms to systematically identify and reward competency-driven achievements. Recognition can here take various forms (e.g., promotions, bonuses, benefit packages, recognition awards, covering conference travel costs, reimbursing publications costs, and informal acknowledgments), through which organisations can greatly stimulate the performance of the involved parties.

By embedding competency mapping into performance metrics and recognition systems, organisations can indeed create an integrated framework where individuals’ potentials are transformed into collective achievement. The most significant characteristic of this approach is that it does not only drive immediate results but also ensures long-term sustainability by creating and developing a skilled, motivated, and innovative workforce, where are the parties involved are taken good care of.

Figure 2 represents the alignment of strategic objectives, competency mapping, performance metrics, and recognition systems to drive organisational success where both parties involved are well-aware of their assets and willing to pursue mutually beneficial goals where their aspirations, motivation, intentions, desires, dreams, competencies, and skills can be of great value.

As we can see in the infographic above, competency mapping is not a homogeneous unit but a linear sequence that encompasses a succession of various interrelated processes, that altogether stimulate the eventual success of this or that organisation at hand.

7. The Dynamic Nature of Competency in Knowledge Communities

Competency requirements are constantly developing (and self-organising) because of technological advancements, globalisation, digitalisation, and the changing nature of work. As we have discussed and analysed in [

8], the rise of automation technologies and artificial intelligence necessitates a workforce equipped with skills to complement and collaborate with developing technologies. Globalisation (and, more specifically, moving from individual and local values to group and global community values) demands an intercultural understanding, presupposing a high level of CQ (cultural intelligence), that we will discuss shortly, as well as the ability to navigate complex global landscapes. In addition, the increasing shift towards remote and flexible work models requires strong communication, self- and social-awareness, self-management, and digital literacy skills.

In this dynamic environment, organisations must develop a culture of life-long learning and adaptability. This includes providing employees with opportunities for continuous learning and further development through different training programmes, workshops, and access to professional development resources. Encouraging a growth mindset and a willingness to embrace new skills and knowledge is crucial, as it can be beneficial in the success of any individual. Yet, it is also highly important to point out that globalisation does not refer to the abandonment of cultural values; instead it involves finding a common ground, where the cultural specifics of each and every nation are acknowledged and cherished.

Here, the cultural dimensions of [

33] can be very beneficial in understanding the performances, actions, verbal and non-verbal communicative behaviours of people of different cultural backgrounds, namely, (i) long-term orientations versus short-term orientation, (ii) masculinity versus femininity, (iii) indulgent versus restrained, (iv) the power distance index, (v) individualism versus collectivism, and (vi) uncertainty avoidance, all of which can have a great influence on the verbal and non-verbal behaviour and linguistic choices of interactants in various cross-cultural settings, thereby ensuring smooth interpersonal interactions.

All the aforementioned cultural dimensions are of crucial significance in understanding an individual’s or even an entire nation’s attitude towards diverse situations and, bearing these in mind, we can really make sense of the underlying factors that can make us become more socially and self aware and able to cooperate successfully and productively across different cultures and situations in a globalised world.

8. The Strategic Advantage of Competency in Knowledge Communities

When speaking about competency and performance levels in different communities across cultures and situations, we have to bear in mind that we all have different skill-sets and represent different learning types that together can add great value to a company’s performance, while also taking into account cultural, educational, vocational, gender, and personal specifics.

To ensure that targets are met successfully and efficiently, we have to take into consideration that for a company or an educational institution to excel in their endeavours, they have to have quantifiable objectives, measurable goals, and accountable strategies, all of which guarantee success in achieving the goals set. This is correlated with the assumption that goals, missions, and visions cannot be set without taking into account the human factor: humans are not devoid of emotions and feelings possessing different skill-sets, and by valuing the range of benefits offered by humans, we can truly promote talent and achieve our short-term and long-term objectives (see [

34]).

Moreover, in relation to this, we have to state that our human knowledge is not purely rational and that it also encompasses emotional elements, which provide us with very important pieces of information for logical thinking. Here, we can mostly speak of the dichotomy of

rationality and

emotionality; see [

35]. Usually, there is a balance between these two, but in the heat of an emotional moment or in response to an external or internal trigger, the balance therein can be lost and emotions can gain power over the rational part of the brain, which is mostly the left hemisphere, emotions mainly belonging to the right hemisphere of the human brain. Thus, we can deduce that for harmonious cooperation between the two, there should be a balance between the IQ (the rational quotient) and EQ (the emotional intelligence). Thus, in essence, as Daniel Goleman asserts, we can state that we have two minds, namely, the

rational mind (representing our IQ, the rational quotient) and the

emotional mind (representing our EQ, the emotional quotient); see [

36].

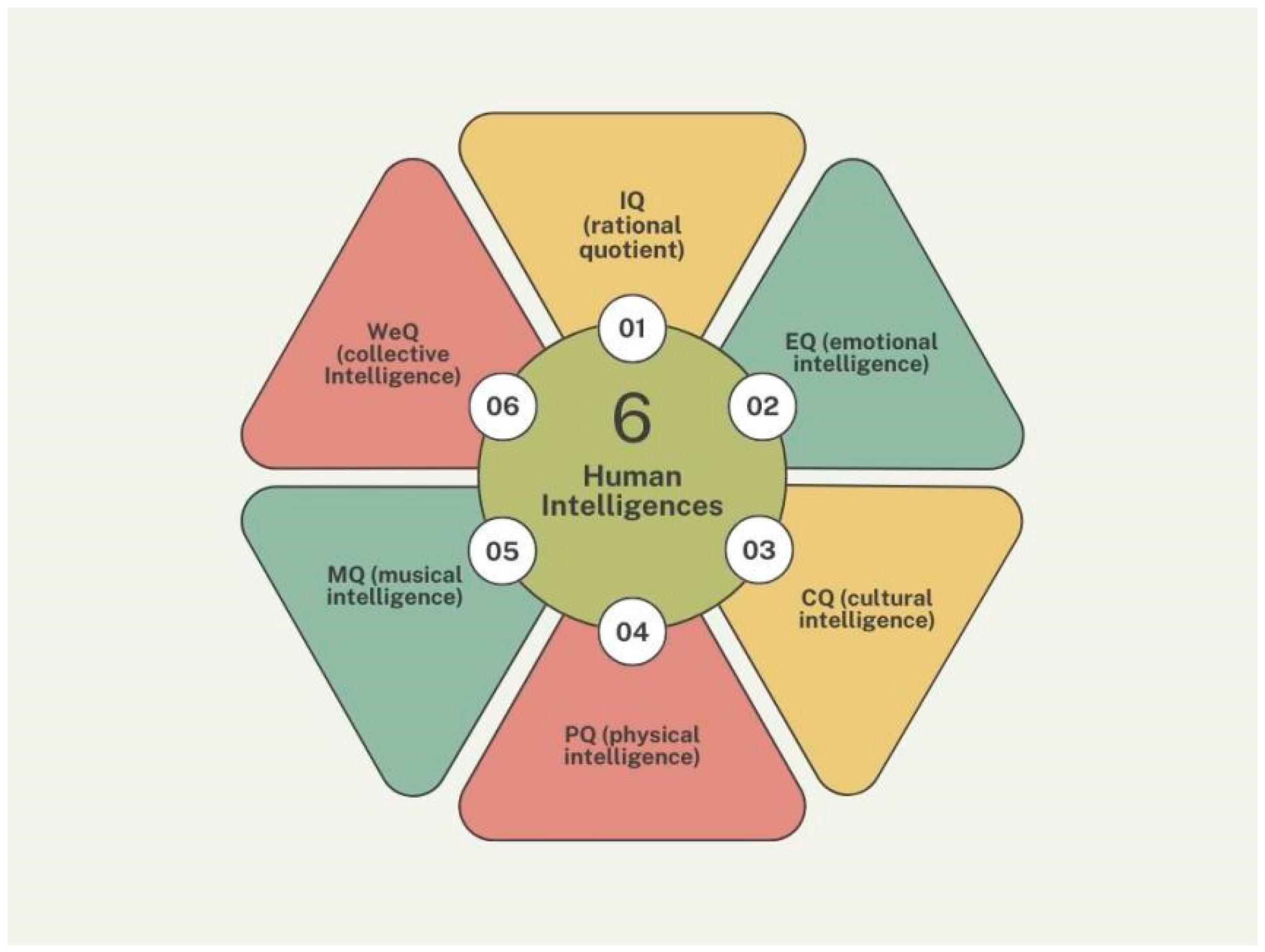

In this respect, as it can be detected in

Figure 3 adduced below, it is of the utmost importance to state that more and more people are referring to EQ (emotional quotient) as EI (emotional intelligence), with the initial letters of the notion in the abbreviation: in the German language, it has always been referred to as “EI” (emotionale Intelligenz), but nowadays, this is becoming the case in the English language, as well. In the French language, it is referred to as IE (intelligence émotionnelle). Concerning this change in the abbreviation, we are inclined to believe that this was to showcase that humans (as we have EI) with diverse soft skills and human skills are closer to technology (AI, artificial intelligence) than ever before, with the introduction of the concept of

affective computing, otherwise called ‘Emotion AI’, wherein AI technologies not only understand human emotions but also respond to them empathetically, logically, and emotionally ([

37]).

Furthermore, human intelligence is formed not only from the interconnection between (i) IQ, our

rational quotient, and (ii) EQ, which is our

emotional intelligence, but also some other quotients, like (iii) SQ,

social intelligence, which, with EQ, forms social awareness and relationship management components, or our

spiritual quotient, which is also sometimes referred to as ‘spiritual intelligence’ since the social aspect is already encompassed in our EQ skills, (iv) PQ, which is our

physical quotient, (v) CQ, which is our

cultural intelligence in terms of being able to recognise our cultural differences and adapt to them to harmoniously cooperate in cross-cultural settings ([

38]), and (vi) MQ, which is our

musical intelligence, i.e., our ability to perceive, distinguish, transform, and express sounds and musical forms, in addition to a capacity to discern rhythm, pitch, and timbre ([

39]), as well as (vii) WeQ, which is our

collective intelligence ([

40]), which is the sum of individuals’ intelligence within a group in a certain organisation; see [

41].

As a matter of fact, all the aforementioned ‘intelligences’ add a great value to human competencies, and all of them are very important and greatly stimulate the functioning of the other quotients. For example, if one has gone in for piano classes but has not become a Johann Sebastian Bach or Johann Strauss, this does not mean that one has failed; on the contrary, research shows that in those of us who have a high MQ (musical intelligence), the neural interconnections are functioning better, and we comprehend the world around us from a very creative viewpoint. Also, it is said that bilingualism, multilingualism, and plurilingualism greatly stimulate the functioning of our IQ, as they also lead to stronger neural connections in our brain circuits; see [

42,

43]. The same holds true for PQ (physical intelligence); research shows that physical exercise can greatly stimulate the generation of new innovative ideas and ensure the better functioning of our higher cognitive processes by means of supplying the brain with enough oxygen and blood; even a mere walk in the fresh air can greatly stimulate the enhancement of our skills and better functioning of our higher cognitive processes. Also, our social skills (SQ) stimulate the generation of happy hormones such as oxytocin that ensure our psychological well-being, so that we can happily thrive in our endeavours: this is especially essential since we perform better when we are happy.

All this suggests that the aforementioned ‘intelligences’ are very tightly interrelated and intertwined and that the stimulation of one of them can greatly stimulate the functioning of the others. Last but not least, thinking collectively and benefiting from WeQ (our collective intelligence) can immensely stimulate the generation of brighter ideas; the strength of all the group members is of utmost importance and is essential in building stronger communities across cultures and situations.

9. Limitations

When speaking of the high importance of the aforementioned aspects of human intelligence, we should also mention that sometimes it can become a real challenge to measure them in separation and to draw a distinct divide between them, since they usually function in unison. Here, the advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) can help us in the future to gain deeper insights into the distinct functions and characteristic features of these ‘intelligences’.

The measurement of competencies, particularly interconnected intelligences such as emotional (EQ), social (SQ), and cultural intelligence (CQ), poses significant challenges due to their overlapping and dynamic nature. These intelligences often function in unison, making it difficult to isolate and quantify their individual contributions to organisational performance. For instance, an employee’s emotional intelligence, assessed through self-reported surveys, may be influenced by personal biases. This can lead to inaccuracies that could misguide competency mapping efforts. Such measurement difficulties can result in training programmes that fail to address the precise needs of the workforce and will not equip them with the skills that they need to develop a better picture of themselves, others, and the company at large. Additionally, the rapid evolution of industries further complicates assessments, as technical competencies, like proficiency in emerging technologies, may quickly become outdated, requiring constant recalibration. To address these limitations, organisations can leverage advanced tools, such as AI-driven analytics for sentiment analysis, to measure complex competencies like cultural intelligence with greater precision. Furthermore, integrating multiple data sources, such as 360-degree feedback from peers and managers, enhances the reliability of assessments. By adopting these strategies, organisations can refine competency mapping processes, ensuring that they remain robust, competent, compatible, just, and aligned with the goal of fostering knowledge-driven environments.

10. Conclusions

In conclusion, the mission and vision, as well as the values and goals, of a company are of great importance, and to foster employee retention, there should be a match, to meet the expected targets. Also, to lead a sustainable business, it is of great importance to pay attention to the emotional capital of the people involved in a company alongside the financial and human capitals.

Here, the competencies (both hard skills and soft skills) are of great value, with all the skill-sets being beneficial for successful cooperative and communicative interaction (both human–human and human–machine). Moreover, there are several strategies and tools to measure competency, and competency mapping is not merely a static exercise; it is a dynamic and iterative process that ensures an ongoing alignment between individual capabilities and organisational goals.

Thus, regular reviews of competency frameworks and periodic reassessments of the workforce are critical in adapting to changing business environments. By leveraging competency mapping as a strategic tool, organisations can not only enhance knowledge development, but also build a resilient, stronger, and future-ready workforce.

Furthermore, to summarize, we can firmly conclude that all of the interconnected ‘intelligences’ discussed in this paper make up the basis of the generation of competencies that help us operate successfully in life. Moreover, the active functioning of most of them ensures the acquisition of new skills that make up the basis of our knowledge, which is stored in our long-term memory and helps us to learn new things in life more easily, which is of great relevance in efficient human co-existence.

Therefore, our framework advances knowledge management by integrating emotional, rational, and cultural factors into competency mapping, offering a structured approach to align individual skills with organisational strategies, as well as organisational short-term and long-term targets. By synthesising diverse perspectives from organisational theory and human intelligence, it provides a practical model for fostering innovation and enhancing adaptability in modern workplaces. Organisations can thus use this framework to identify and develop competencies that enhance knowledge sharing, such as better self-awareness and self-regulation, better social awareness and relationship management, as well as resultant stronger collaboration skills that improve project efficiency or emotional intelligence that strengthens the overall team dynamics and eventual overall success. This approach supports the journal’s mission to explore innovative knowledge management strategies that can truly be very beneficial, in our opinion, in this globalised world.

Besides, competency mapping stands as a transformative tool for driving knowledge in modern organisations, aligning individual competencies with strategic goals to create vibrant ecosystems for knowledge creation and sharing. By systematically identifying, assessing, developing and improving competencies—ranging from technical expertise to emotional and cultural intelligences—organisations can unlock the full potential of their workforce. This alignment not only enhances immediate performance, but also builds a resilient, competent, and future-ready workforce capable of navigating technological advancements and global complexities. Our analysis, therefore, highlights that competencies, when mapped effectively, foster continuous learning and innovation, as evidenced by studies showing that targeted training programmes, informed by competency assessments, improve knowledge retention by 23%. Furthermore, integrating competency mapping into performance metrics, such as those outlined in the Balanced Scorecard framework, ensures that individual efforts contribute to collective organisational success. Thus, to sustain this impact, organisations must embrace iterative competency mapping processes, regularly reassessing workforce capabilities to adapt to evolving business landscapes. This way, they can transform individual potential into collective intellectual capital, securing a competitive edge in knowledge-driven environments.

In summary, we strongly encourage organisations to adopt this dynamic approach, fostering a culture where knowledge, skills, and human connections thrive, to meet both present and future challenges, which will not only stimulate overall organisational success, but will also be very beneficial for the included individuals’ knowledge, health and well-being, which is one of the prerequisites of success for any establishment.