Economic Importance of Aquaculture in Spain Compared to Other European Countries: European Court of Auditors’ Report on Aquaculture in the EU

Abstract

:1. Introduction

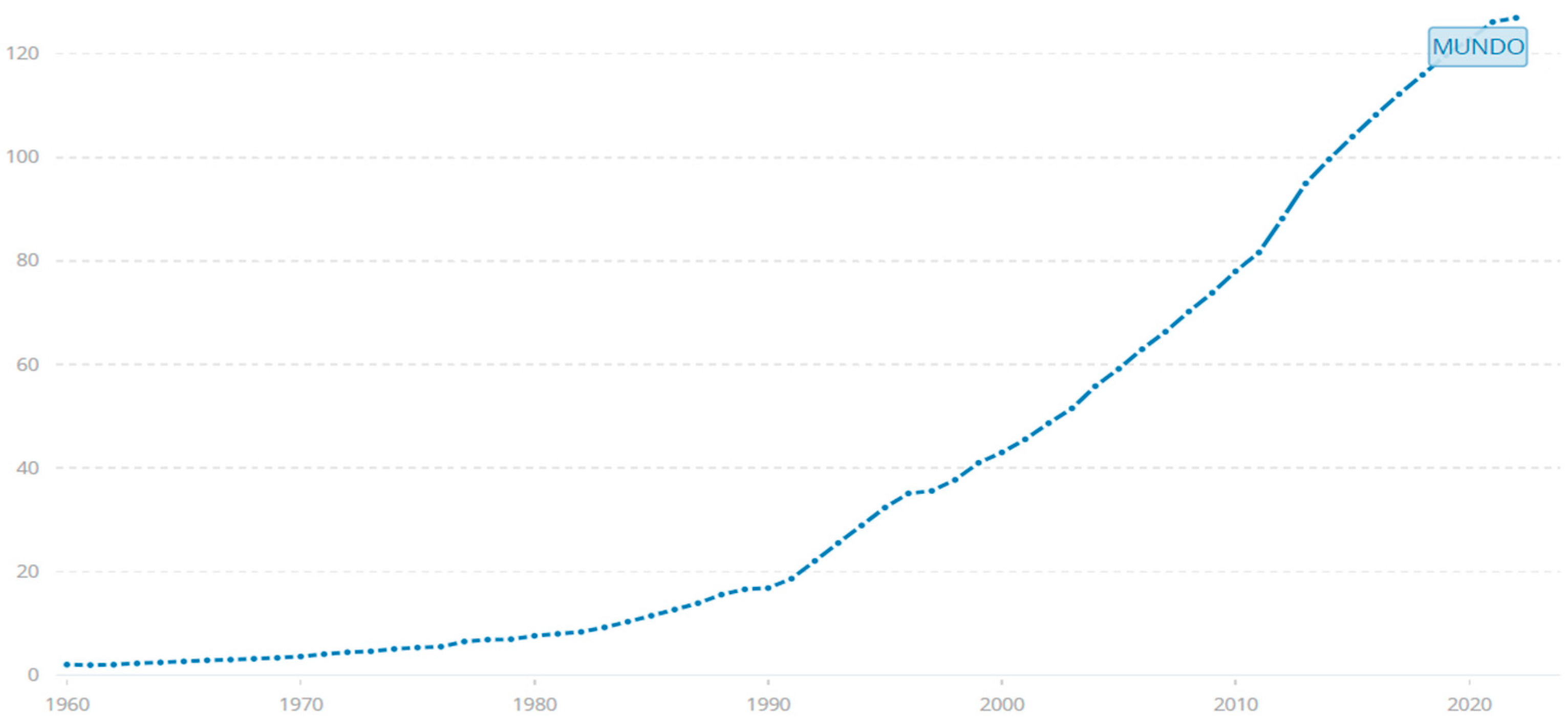

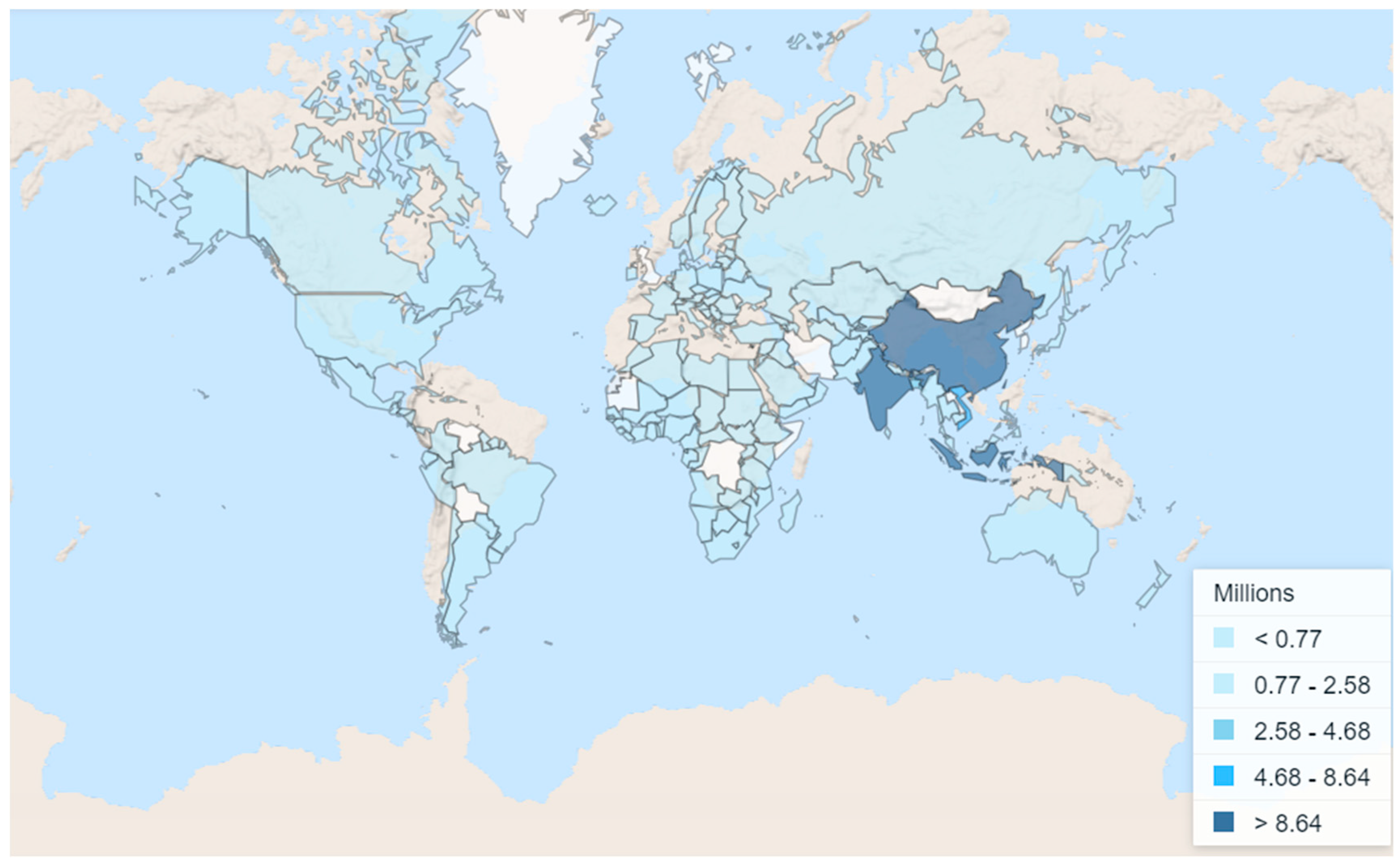

2. The Importance of Aquaculture in the EU

3. Main Definitions of Aquaculture Activity

3.1. Key Concepts [8]

- Aquaculture Products: Products derived from aquaculture animals, which may include breeding materials such as eggs and gametes or products intended for human consumption.

- Marine Crops: Activities related to the reproduction or growth of one or more species of marine fauna and flora or those associated with them.

- Vivero: A floating device or bottom-fixed frame used for cultivating marine species through ropes, boxes, or similar attachments.

- Cage: A floating structure or bottom installation that retains marine fauna species for cultivation using nets, grids, bars, or other systems.

- Breeder: A facility designed to stimulate spawning and induce laying or any other method aimed at enhancing reproduction to obtain marine species during their early life cycles.

- Seedbed: An establishment for pre-fattening and acclimatization of juveniles obtained from hatcheries; these juveniles are referred to as “seed” when destined for fattening.

3.2. Types of Aquaculture [8]

- Aquaculture can be categorized by type as follows:

- Polloducts: Cultivation of bivalve mollusks.

- Mitiliculture: Mussel cultivation.

- Venericulture: Clam cultivation.

- Ostriculture: Oyster farming.

- Pisciculture: Fish farming.

- Salmoniculture: Salmon and trout farming.

- Cypriniculture: Cultivation of cyprinids (e.g., carps).

3.3. By Cultural Density

- Intensive Cultivation: A production system that aims for high output in the smallest possible space and within the shortest time frame.

- Extensive Cultivation: A production system characterized by minimal human intervention, primarily involving two functions: the capture of postlarvae and/or fry and the harvesting of adults once they reach commercial size.

- Semi-Intensive Cultivation: A system that combines controlled feeding with the addition of fry and water renewal.

3.4. By Type Crops

- Cantabrian Coast and Northwest Region: Mussel farming on rafts and turbot farming on land farms predominate. Other notable species include oysters cultivated on rafts or other floating structures, as well as clams and cockles grown in crop parks. Pectenids, salmon, and emerging octopus farming (with experimental crops) are of secondary importance. Additionally, red seabream is identified as a species with potential for future development. Galicia is the Autonomous Community that focuses predominantly on these crops.

- Warmer Mediterranean and South-Atlantic Areas: Gilt-head bream and sea bass are primarily cultivated on land farms and in floating cages alongside other species, such as oysters, clams, mussels, and prawns, which are of secondary importance. Bluefin tuna, octopus, dentex, and sole are species expected to develop further in the coming years. Notably, Andalusia produces gilt-head bream and sea bass in estuaries and ancient salt flats dedicated to fish breeding due to their exceptional biogeographical conditions.

- Canary Islands: Gilt-head bream and sea bass are produced in floating cages. The temperate waters throughout the year provide favorable conditions for these crops.

4. Theoretical Framework

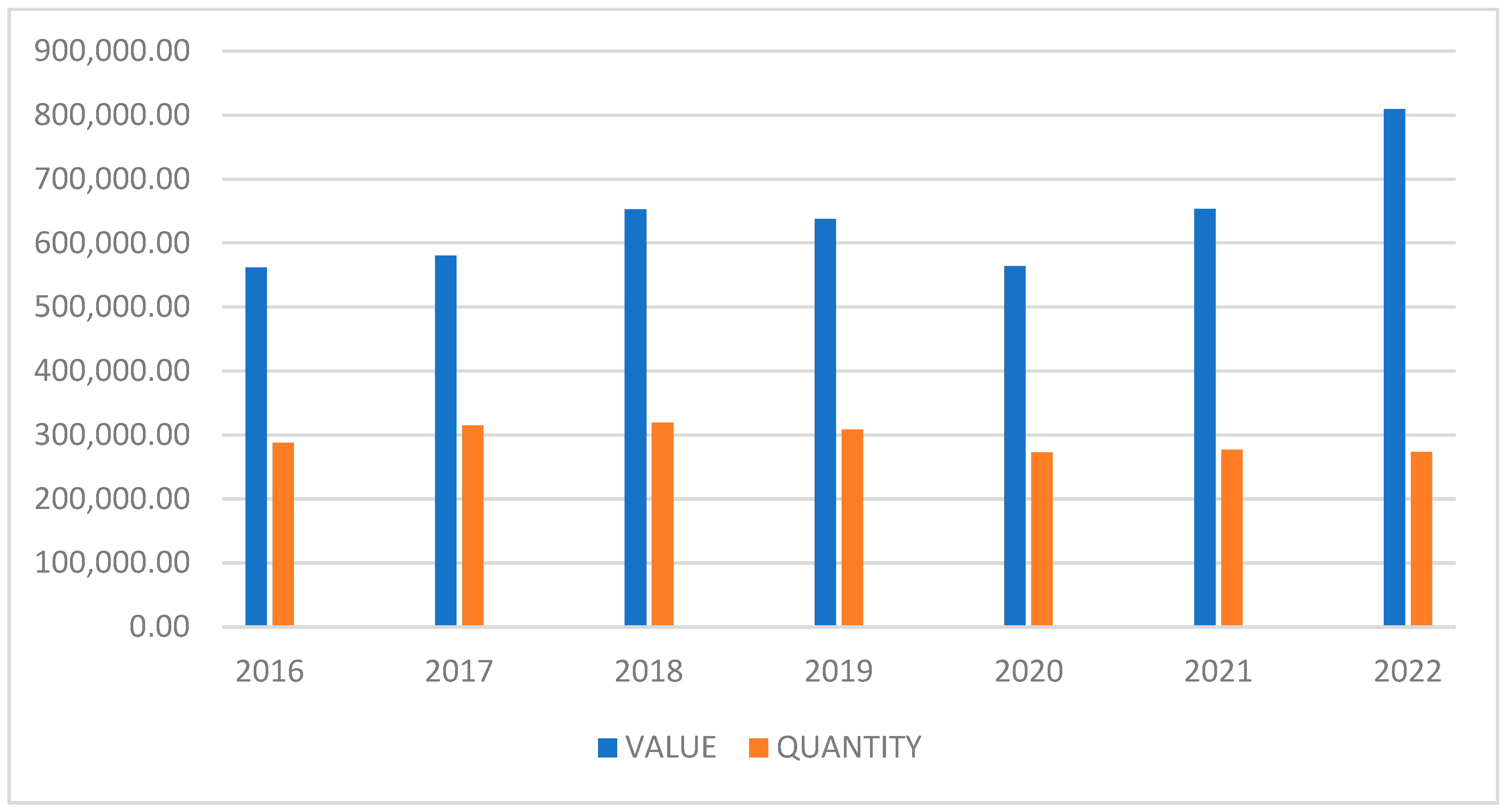

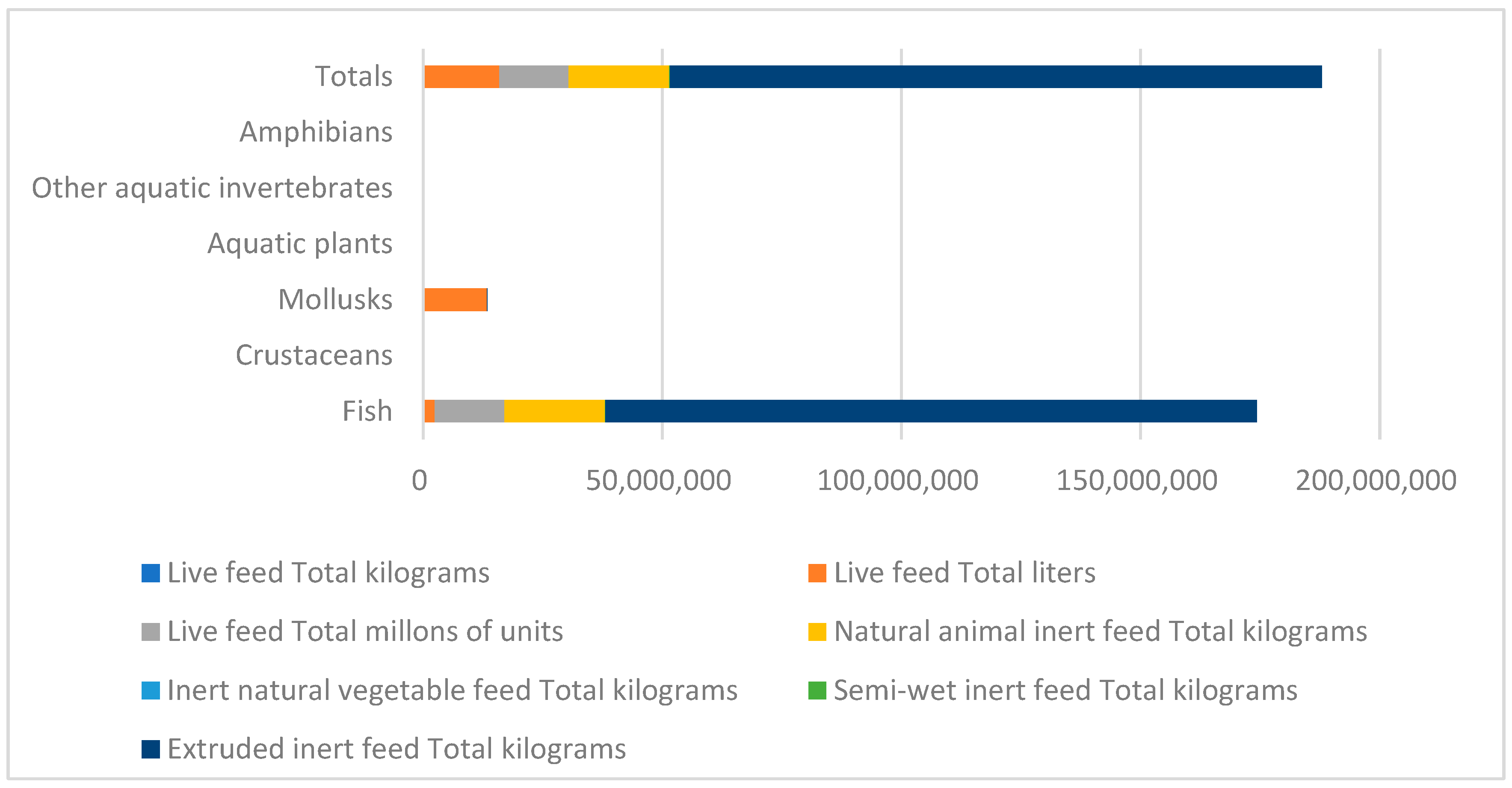

5. Production and Demand for Aquaculture Products in the EU and Spain

- (1)

- To create long-term secure jobs, particularly in fishery-dependent areas, and to increase employment in aquaculture by generating between 8000 and 10,000 full-time equivalent positions during the period from 2003 to 2008 [38].

- (2)

- To ensure that consumers have access to healthy, safe, and high-quality products while promoting high standards of animal health and welfare.

- (3)

- To foster an environmentally friendly industry.

6. The Policy of Financial Support for EU Aquaculture

7. Financial Plans to Promote Aquaculture in the EU: Guidelines Adopted by the Commission

7.1. Period 2014–2020: The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF)

- The simplification of administrative procedures.

- Ensuring sustainable development and growth of aquaculture through coordinated space management.

- Strengthening the competitiveness of EU aquaculture.

- Promoting a level playing field for EU economic operators by leveraging their competitive advantages.

- “Protection and restoration of aquatic biodiversity, enhancement of aquaculture-related ecosystems, and promotion of resource-efficient aquaculture.”

- “Promotion of aquaculture with a high level of environmental protection, as well as the promotion of animal health and welfare, public health, and safety.”

7.2. Period 2021–2027: The European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF)

8. The European Court of Auditors’ Report on EU Aquaculture Policy: Main Results

- Member States’ spatial planning and licensing procedures continue to hinder the growth of aquaculture. The lengthy procedures for obtaining the necessary licenses to start an aquaculture activity have been repeatedly recognized since 2011 as an obstacle to the development of the aquaculture sector and one of the reasons for the low absorption of EU funds. In the 2014–2020 period, for example, no new permits were granted for marine aquaculture in Galicia, Italy, and Poland.

- There has been a significant increase in financial funds for aquaculture in the EU, but absorption rates and project selection standards have been low. The amounts allocated through the EMFF and EMFAF are much higher than those spent up to 2014, both in absolute terms and relative to the total funding available for each instrument.

- The EU spent around EUR 300 million in the aquaculture sector from 2000 to 2006 and around EUR 350 million from 2007 to 2013. These amounts represent between 9% and 1% of total expenditure under the Financial Instrument for Fisheries Guidance (FIFG) and the EFF, respectively. In the 2014–2020 period, based on the operational programs initially approved by the Commission, the allocation to Union Priority 2 was EUR 1200 million, around 22% of the total EMFF allocation. The initial allocation to aquaculture for the 2014–2020 period was more than three times the total spent in the 2007–2013 period [46].

- Neither the Commission’s impact assessment accompanying the EMFF proposal nor the operational programs of the Member States have sufficiently demonstrated the need for such a substantial increase in funds available to the sector. The overall allocation to aquaculture in the EU decreased by approximately EUR 158 million by the end of 2022, representing 13% of the initial allocation. Four of the six Member States audited by the European Court of Auditors reduced their allocations to aquaculture, particularly Italy (33%) and Poland (32%). Conversely, allocations increased in France (by 44%) and Romania (by 8%). The initial allocation of the EMFAF (2021–2027) has decreased compared to that of the EMFF (2014–2020) but remains significantly higher than the amounts spent from 2000 to 2013.

- The absorption rate of financial resources was low compared to other priorities despite the increase resulting from COVID-19 mitigation measures. According to the Commission, the aquaculture sector was particularly affected by market disturbances due to a significant drop in demand caused by the COVID-19 outbreak. In April 2020, the Commission proposed a set of EU fisheries and aquaculture support measures to address the impact of the outbreak, including increased flexibility for Member States to reallocate existing financial resources to new specific measures aimed at compensating aquaculture farmers for the suspension of production and covering additional costs.

- Almost all eligible projects were financed by Member States, as the selection criteria were not very demanding. The most common allocations in the audited countries included “productive investments in aquaculture”, such as investments in modernization or the development of closed-loop recirculation systems. Other popular measures included the ‘provision of environmental services by the aquaculture sector,’ which primarily concerns the conservation and improvement of the environment and biodiversity (Poland and Romania), ‘innovation’ (Spain, Greece, and France), ‘public health measures’ (Greece), and ‘increasing the potential of aquaculture production areas’ (Italy). However, the selection criteria were not rigorous, as no overall minimum score was applied when selecting the submitted projects.

- Despite the aforementioned points, the Commission has established greater flexibility for countries to determine their own eligibility criteria for projects during the 2021–2027 period (EMFAF) [42].

- EU aquaculture production is stagnating, and there is insufficient reliable data to evaluate whether the sector is developing in a more sustainable manner. Between 2014 and 2020, EU aquaculture production volumes exhibited minimal growth.

- The performance of the EMFF during the 2014–2020 period cannot be assessed due to a lack of adequate monitoring data. The European Court of Auditors raised concerns regarding the reliability of the original data provided by the audited Member States, as well as the associated information systems.

9. Discussion and Conclusions

- Support Member States in Overcoming Barriers to the Sustainable Development of EU Aquaculture.

- 2.

- Enhance the Effective Allocation of EU Funds as a Tool to Achieve EU Aquaculture Policy Objectives.

- 3.

- Enhance Monitoring of EU Funding Performance and Environmental Sustainability

- Support Member States in addressing obstacles to the sustainable development of EU aquaculture, particularly by promoting best practices related to environmental strategies, licensing procedures, and maritime spatial planning. This recommendation accurately reflects the European Court of Auditors’ call for the Commission to implement deregulatory measures aimed at eliminating bureaucracy and administrative barriers arising from interventionist policies in the Member States. These policies, which are supported by certain lobbying groups, present significant challenges to the development of the primary sector in Europe.

- Improve the targeting of EU funds as a tool to achieve the objectives of EU aquaculture policy and multi-annual national strategic plans for aquaculture. It appears somewhat inconsistent that while the Court of Auditors advocates for greater efficiency in the allocation of European funds, the Commission has simultaneously granted Member States increased autonomy in their application.

- Enhance the monitoring of EU funding performance and its alignment with environmental sustainability objectives.

10. Further Research

11. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AWUS | Annual Work Units |

| CFP | Common Fisheries Policy |

| ECA | European Court of Auditors |

| EFF | European Fisheries Fund |

| EMFAF | European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund |

| EMFF | European Maritime and Fisheries Fund |

| EUMOFA | European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| SAE | Survey of Aquaculture Establishments |

References

- FAO. Fishery Statistical Time Series, Statistical Collection; Fisheries and Aquaculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. World Population Review. Fishing Industry by Country. 2024. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/fishing-industry-by-country (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- FAO. El Estado Mundial de la Pesca y la Acuicultura: La Transformación Azul en Acción; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138817-4. [Google Scholar]

- EUMOFA (European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products). The EU Fish Market 2022 Edition. 2022. Available online: https://eumofa.eu/documents/20178/521182/EFM2022_EN.pdf? (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Seguridad y Salud en el Trabajo (INSST). NTP 623: Prevención de Riesgos Laborales en Acuicultura; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva-Teles, A.; Xing, S.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Peres, H.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Mai, K.; Kaushik, S.J.; Xue, M. Essential amino acid requirements of fish and crustaceans, a meta-analysis. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 16, 1069–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, H.; Castro, C.; Salgado, J.M.; Filipe, D.; Moyano, F.; Ferreira, P.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Belo, I.; Peres, H. Application of fermented brewer’s spent grain extract in plant-based diets for European seabass juveniles. Aquaculture 2022, 552, 738013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Expert Consultation on Implementation Issues Associated with Listing Commercially-Exploited Aquatic Species on Cites Appendices; Fisheries Report No. 741; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gouvello, R. L’économie Circulaire Appliquée à un Système Socio-Écologique Halio-Alimentaire Localisé: Caractérisation, Évaluation, Opportunités et Défis. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Salmón, I.; Laso, J.; Campos, C.; Fernández-Ríos, A.; Hoehn, D.; Margallo, M.; Irabien, A.; Aldaco, R. How to achieve the sustainability of the seafood sector in the European Atlantic Area? IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1196, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, J. Life Cycle Assessment as applied to environmental choices regarding farmed or wild-caught fish. CABI Rev. 2013, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Leung, P.; Pan, M.; Pooley, S. Economic Linkage Impacts of Hawaii’s Longline Fishing Regulations. Fish. Res. 2005, 74, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-de-la-Fuente, L.; Fernández-Vázquez, E.; Ramos-Carvajal, C. A methodology for analyzing the impact of the artisanal fishing fleets on regional economies: An application for the case of Asturias (Spain). Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K.; Yoo, S.-H. The role of the capture fisheries and aquaculture sectors in the Korean national economy: An input–output analysis. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, P.; Pooley, S. Regional Economic Impacts of Reductions in Fisheries Production: A Supply-Driven Approach. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2001, 16, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, N.; Stoyanova, K.A.; Wagner, C. Cost–benefit analysis of the Greenland offshore shrimp fishery. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. C—Food Econ. 2011, 8, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Galán, M.-d.-M. Modelo de Desarrollo Empresarial Fundamentado en I+D Aplicada en Acuicultura. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Garza-Gil, M.D.; Surís-Regueiro, J.C.; Varela-Lafuente, M.M. Using input–output methods to assess the effects of fishing and aquaculture on a regional economy: The case of Galicia, Spain. Mar. Policy 2017, 85, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grealis, E.; Hynes, S.; O’Donoghue, C.; Vega, A.; Van Osch, S.; Twomey, C. The economic impact of aquaculture expansion: An input-output approach. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Huang, H.; Leung, P. Understanding and Measuring the Contribution of Aquaculture and Fisheries to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). 2019. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/077302f4-9d34-488f-baed-f052dde78194/content (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Bagoulla, C.; Guillotreau, P. Maritime transport in the French economy and its impact on air pollution: An input-output analysis. Mar. Policy 2020, 116, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, D. Intelligent fish farm—The future of aquaculture. Aquacult. Int. 2021, 29, 2681–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.J.; Yoo, S.H.; Chang, J.I. The role of the maritime industry in the Korean national economy: An input–output analysis. Mar. Policy 2005, 29, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surís-Regueiro, J.C.; Santiago, J.L.; González-Martínez, X.M.; Garza-Gil, M.D. An applied framework to estimate the direct economic impact of Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy 2021, 127, 104443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronen, M.; Vunisea, A.; Magron, F.; McArdle, B. Socio-economic drivers and indicators for artisanal coastal fisheries in Pacific island countries and territories and their use for fisheries management strategies. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, S.M.; Fenichel, E.P.; McCauley, D.J.; Biedenweg, K.; Brumbaugh, R.D.; Costello, C.; Joyce, F.H.; Goldman, E.; Mannix, H. Boundary spanning among research and policy communities to address the emerging industrial revolution in the ocean. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, K.; O’Donoghue, C. The role of the marine sector in the Irish national economy: An input–output analysis. Mar. Policy 2013, 37, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Pettersen, J.B.; Brandão, M.; Ma, X.; Røberg, S.; Frostell, B. Life cycle assessment of recirculating aquaculture systems: A case of Atlantic salmon farming in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Beusen, A.H.; Liu, X.; Bouwman, A.F. Aquaculture Production is a Large, Spatially Concentrated Source of Nutrients in Chinese Freshwater and Coastal Seas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1464–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.-B.; de-Moraes, G.-I. The Brazilian coastal and marine economies: Quantifying and measuring marine economic flow by input-output matrix analysis. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 213, 105885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacruz-Iglesias, A. Importancia de la pesca y la acuicultura en España. Biodivers. Mar. Riesgos Amenazas Oportunidades 2020, 33, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Espinos, F. La acuicultura como activo económico y social. Mediterráneo Econ. 2020, 33, 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Vas, R. Opciones Reales y Economía Sostenible: Aplicación al Sector de la Acuicultura Gallega. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Vigo, Vigo, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Raffray, M.; Martin, J.C.; Jacob, C. Socioeconomic impacts of seafood sectors in the European Union through a multi-regional input output model. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 850, 157989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUMOFA (European Market Observatory for Fishery and Aquaculture Products). The EU Fish Market 2023 Edition; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bordonado-Bermejo, M.-J.; Ortega-Larrea, A.-L. Toward a New Sustainable Production and Responsible Consumer in the Food Sectors: Sustainable Aquaculture. In Sustainable Development Goals in Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food of Spain. Boletín Mensual de Estadística. March 2024. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/estadistica/temas/publicaciones/bme-2024-03-marzo_tcm30-679573.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- EU (European Union). A Strategy for the Sustainable Development of European Aquaculture COM(2002) 511. 19 September 2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=LEGISSUM:l66015 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- EU (European Union). EUR-Lex Access to European Union Law. Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the Common Fisheries Policy, amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1954/2003 and (EC) No 1224/2009 and Repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 2371/2002 and (EC) No 639/2004 and Council Decision 2004/585/EC. 2013. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/1380/oj (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- EMFF (The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund). The European Maritime and Fisheries Fund: Financial Instruments. 2020. Available online: https://www.fi-compass.eu/sites/default/files/publications/EMFF_The_european_maritime_and_fisheries_fund_EN.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- EMFAF (The European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund). The European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund. European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund for 2021–2027. 2025. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/funding-tenders/find-funding/eu-funding-programmes/european-maritime-fisheries-and-aquaculture-fund_en (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- EMFAF (The European Maritime, Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund). EMFAF Programmes 2021–2027. Food, Farming, Fisheries. 2020. Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/funding/emfaf-programmes-2021-2027_en (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- European Court of Auditors. Special Report 25/2023: EU Aquaculture Policy—Stagnating Production and Unclear Results Despite Increased EU Funding. 11 November 2023. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/publications?ref=sr-2023-25 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- EU (European Union). EUR-Lex Access to European Union Law. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/glossary/open-method-of-coordination.html. (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- European Commission. Aquaculture Guidelines. Food, Farming, Fisheries. January 2025. Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/ocean/blue-economy/aquaculture/aquaculture-guidelines_en (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- European Court of Auditors. The Effectiveness of European Fisheries Fund Support for Aquaculture; Special Report 10/2014; European Unión: Luxembourg, 2014; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General Maritime Affairs and Fisheries; The Joint Research Centre. The EU Blue Economy Report 2021; European Commission, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

| Mussels | 37% |

| Rainbow trout | 17% |

| Oysters | 9% |

| Golden | 9% |

| European seabass | 7% |

| Tent | 7% |

| Algae | <0.05% |

| Total Production (in Volume) | Total Production (in Value) | Total Production (Million Tons) |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | 25% | 20% |

| France | 18% | 20% |

| Greece | 12% | 15% |

| Italy | 11% | 11% |

| Others (Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Portugal, Ireland, Finland, Denmark) | 33% | 39% |

| TOTAL | 100% | 100% |

| Origin of Water | Type of Establishment | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stab. with Culture | Stab. with Production | Stab. with Culture | Stab. with Production | Stab. with Culture | Stab. with Production | Stab. with Culture | Stab. with Production | Stab. with Culture | Stab. with Production | ||

| By sea | On dry land | 37 | 32 | 36 | 32 | 37 | 31 | 38 | 29 | 37 | 27 |

| In natural enclaves | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| For horizontal cultivation | 50 | 44 | 50 | 44 | 46 | 42 | 40 | 36 | 39 | 37 | |

| For vertical cultivation | 3.737 | 3.663 | 3.737 | 3.634 | 3.718 | 3.627 | 3.721 | 3.627 | 3.729 | 3.631 | |

| Growing in cages | 45 | 43 | 46 | 42 | 44 | 43 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 40 | |

| Sum | 3.870 | 3.783 | 3.870 | 3.753 | 3.845 | 3.743 | 3.839 | 3.730 | 3.845 | 3.735 | |

| Of brackish intertidal zone | On dry land | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| In natural enclaves | 44 | 34 | 42 | 33 | 38 | 32 | 43 | 41 | 38 | 36 | |

| For horizontal cultivation | 1.096 | 1.085 | 1.305 | 1.302 | 1.182 | 1.173 | 1.282 | 1.265 | 1.157 | 1.134 | |

| For vertical cultivation | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Growing in cages | |||||||||||

| Sum | 1.149 | 1.126 | 1.355 | 1.341 | 1.226 | 1.209 | 1.330 | 1.309 | 1.200 | 1.173 | |

| TOTAL MARINA | 5.019 | 4.909 | 5.225 | 5.094 | 5.071 | 4.952 | 5.169 | 5.039 | 5.045 | 4.908 | |

| Of continental zone | On dry land | 147 | 126 | 144 | 126 | 142 | 126 | 150 | 126 | 153 | 131 |

| In natural enclaves | 51 | 40 | 52 | 42 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 17 | 24 | 18 | |

| For horizontal cultivation | |||||||||||

| For vertical cultivation | |||||||||||

| Growing in cages | |||||||||||

| TOTAL CONTINENTAL | 198 | 166 | 196 | 168 | 167 | 150 | 174 | 143 | 177 | 149 | |

| Total | On dry land | 192 | 164 | 188 | 164 | 185 | 161 | 193 | 158 | 195 | 161 |

| In natural enclaves | 96 | 75 | 95 | 76 | 63 | 56 | 67 | 58 | 62 | 54 | |

| For horizontal cultivation | 1.146 | 1.129 | 1.355 | 1.346 | 1.228 | 1.215 | 1.322 | 1.301 | 1.196 | 1.171 | |

| For vertical cultivation | 3.738 | 3.664 | 3.737 | 3.634 | 3.718 | 3.627 | 3.721 | 3.627 | 3.729 | 3.631 | |

| Growing in cages | 45 | 43 | 46 | 42 | 44 | 43 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 40 | |

| TOTAL AQUACULTURE | 5.217 | 5.075 | 5.421 | 5.262 | 5.238 | 5.102 | 5.343 | 5.182 | 5.222 | 5.057 | |

| 1995 | 2000s | 2010s | 2020 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQUACULTURE | 106 | 110 | 106 | 102 | 102 |

| INLAND FISHERIES | 46 | 40 | 36 | 37 | 32 |

| MARINE FISHING | 322 | 241 | 197 | 180 | 175 |

| UNSPECIFIED | 82 | 85 | 62 | 66 | 69 |

| TOTAL FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE | 554 | 477 | 401 | 385 | 379 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Algarra-Paredes, A.; Ortega-Larrea, A.-L.; Bordonado-Bermejo, M.-J. Economic Importance of Aquaculture in Spain Compared to Other European Countries: European Court of Auditors’ Report on Aquaculture in the EU. Aquac. J. 2025, 5, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5020008

Algarra-Paredes A, Ortega-Larrea A-L, Bordonado-Bermejo M-J. Economic Importance of Aquaculture in Spain Compared to Other European Countries: European Court of Auditors’ Report on Aquaculture in the EU. Aquaculture Journal. 2025; 5(2):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5020008

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlgarra-Paredes, Angel, Ana-Lucia Ortega-Larrea, and María-Julia Bordonado-Bermejo. 2025. "Economic Importance of Aquaculture in Spain Compared to Other European Countries: European Court of Auditors’ Report on Aquaculture in the EU" Aquaculture Journal 5, no. 2: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5020008

APA StyleAlgarra-Paredes, A., Ortega-Larrea, A.-L., & Bordonado-Bermejo, M.-J. (2025). Economic Importance of Aquaculture in Spain Compared to Other European Countries: European Court of Auditors’ Report on Aquaculture in the EU. Aquaculture Journal, 5(2), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj5020008