Barriers to the Export of Farmed Pangasius and Tilapia from Bangladesh to the International Market: Evidence from Primary and Secondary Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

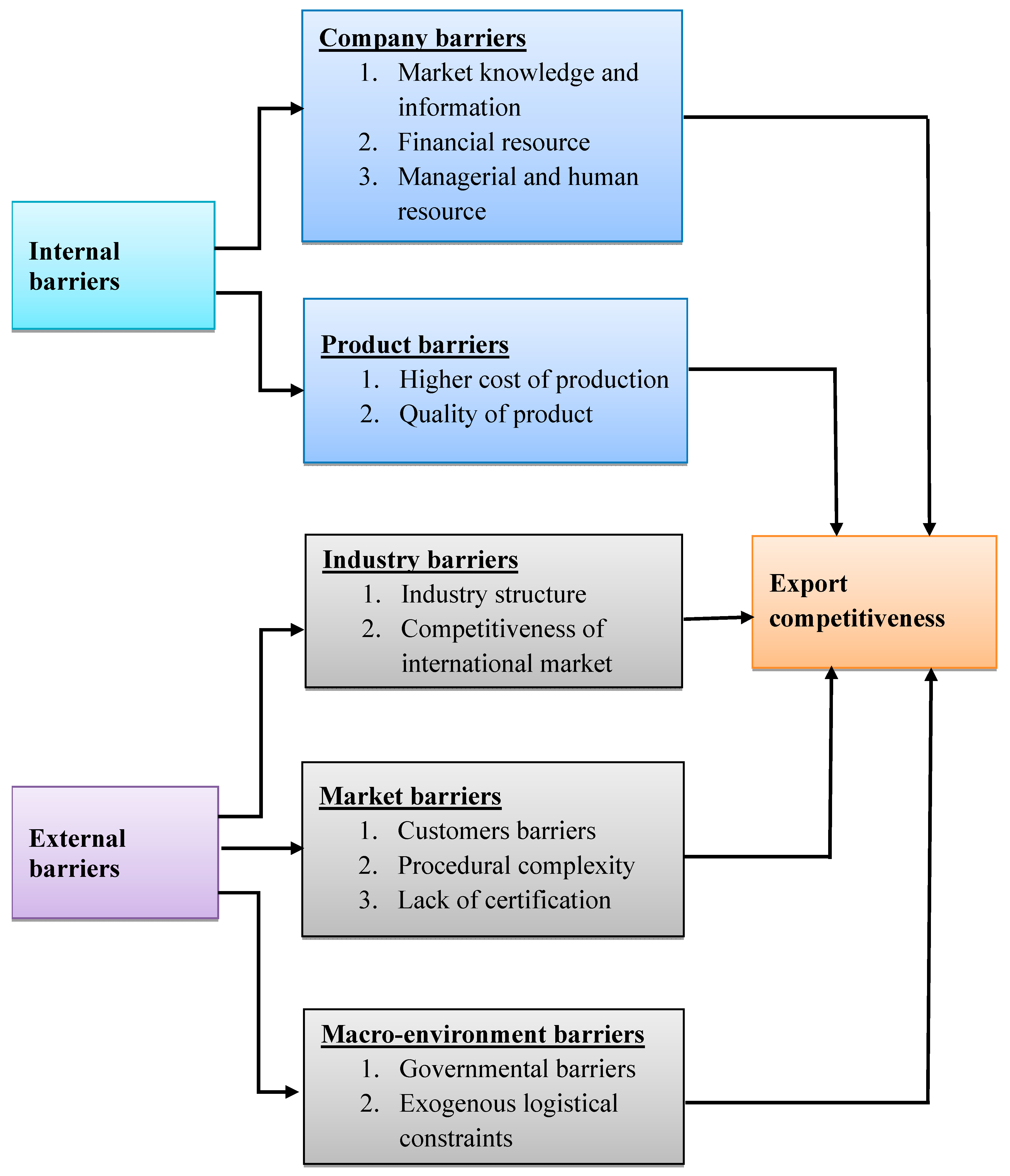

2.2. Conceptual Framework

Concept and Classifying Export Barriers

2.3. Data Collection Techniques

2.3.1. Secondary Information and Literature Search

2.3.2. Primary Data Collection

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Internal Export Barriers of Farmed Pangasius and Tilapia

3.1.1. Company Barriers

Limitation of Market Knowledge and Information

Insufficient Financial Resource

Scarcity of Skilled Managerial and Human Resource

3.1.2. Product Barriers

Higher Cost of Fillet Preparation and Production System

Quality of Product

3.2. External Barriers of Farmed Pangasius and Tilapia

3.2.1. Industry Barriers

Industry Structure

Competitiveness of the International Market

3.2.2. Market Barriers

Customer Barriers

Procedural Complexity of Export

Lack of Standard Aquaculture Certification

3.2.3. Macroenvironment Barriers

Governmental Barriers

Exogenous Logistical Constraints

4. Other Nonexporter Asian Countries

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L.O.J.; Engelhard, G.H.; Thurstan, R.H.; Sturrock, A.M. Widening mismatch between UK seafood production and consumer demand: A 120-year perspective. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2023, 33, 1387–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoque, M.S.; Haque, M.M.; Nielsen, M.; Rahman, M.T.; Hossain, M.I.; Mahmud, S.; Mandal, A.K.; Frederiksen, M.; Larsen, M.P. Prospects and challenges of yellow flesh pangasius in international markets: Secondary and primary evidence from Bangladesh. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, A.F.M.; Fitzsimmons, K. From Africa to the world—The journey of Nile tilapia. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M.; Islam, M.S.; Hossain, M.I.; Jahan, H. Conditions for participation of marginalized households in shrimp value chains of the coastal region of Bangladesh. Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Hossain, M.E.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.T.; Dey, M.M. Shrimp export competitiveness and its determinants: A novel dynamic ARDL simulations approach. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2022, 27, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.T.; Jolly, C.M. Global value chain and food safety and quality standards of Vietnam pangasius exports. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 16, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.Y.; Yuan, Y.M.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.Y. Competitiveness of Chinese and Indonesian tilapia exports in the US market. Aquac. Int. 2020, 28, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatuporn, C. Impact Assessment of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Shrimp Exports in Thailand: An Empirical Study Using Time Series Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.D.; Krishnan, M.; Sivaramane, N.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Kiresur, V.R. Market integration and price transmission in Indian shrimp exports. Aquaculture 2022, 561, 738687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DoF. National Fish Week 2023 Compendium; Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2023; 160p. (In Bangla) [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.T.; Goswami, A.; Rahman, M.S.; Dhar, A.R.; Khan, M.A. Value chain of pangas and tilapia in Bangladesh. J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 2018, 16, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Hossain, M.E.; Prodhan, M.M.H.; Rahman, M.T.; Nielsen, M.; Khan, M.A. Profit and loss dynamics of aquaculture farming. Aquaculture 2022, 561, 738619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, N.T.; Nielsen, M.; Roth, E.; van Nguyen, G.; Solgaard, H.S. The estimate of world demand for Pangasius catfish (Pangasiusianodon hypopthalmus). Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2016, 21, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, B.; Haque, M.M.; Little, D.C.; Sinh, L.X. Certifying catfish in Vietnam and Bangladesh: Who will make the grade and will it matter? Food Policy 2011, 36, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DoF. Yearbook of Fisheries Statistics of Bangladesh, 2020–2021; Fisheries Resources Survey System (FRSS), Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2022; Volume 38, 138p. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.M.; Haque, M.M. Presence of antibacterial substances, nitrofuran metabolites and other chemicals in farmed pangasius and tilapia in Bangladesh: Probabilistic health risk assessment. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.T.; Rasel, M.H.; Dhar, A.R.; Badiuzzaman, M.; Hoque, M.S. Factors Determining Consumer Preferences for Pangas and Tilapia Fish in Bangladesh: Consumers’ Perception and Consumption Habit Perspective. J. Aquat. Food Prod. 2019, 28, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Badiuzzaman; Nielsen, M.; Roth, E. Consumer willingness to pay for quality attributes of pangasius (Pangasianodoan hypophthalmus) in Bangladesh: A hedonic price analysis. Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.; Dey, M.M.; Surathkal, P. Fish price volatility dynamics in Bangladesh. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2022, 26, 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, I.; Nielsen, M.; Bosselmann, A.S. Drivers of captive relationships in the pangasius and tilapia value chains in Bangladesh. Aquaculture 2023, 574, 739721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Tikadar, K.K.; Hasan, N.A.; Akter, R.; Bashar, A.; Ahammad, A.K.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Alam, M.R.; Haque, M.M. Economic Viability and Seasonal Impacts of Integrated Rice-Prawn-Vegetable Farming on Agricultural Households in Southwest Bangladesh. Water 2022, 14, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.A.B.; Ahammad, A.K.S.; Mahalder, B.; Alam, M.M.; Hasan, N.A.; Bashar, A.; Biswas, J.C.; Haque, M.M. Perceptions of the Impact of Climate Change on Performance of Fish Hatcheries in Bangladesh: An Empirical Study. Fishes 2022, 7, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.A.B.; Ahammad, A.K.S.; Bashar, A.; Hasan, N.A.; Mahalder, B.; Alam, M.M.; Biswas, J.C.; Haque, M.M. Impacts of climate change on fish hatchery productivity in Bangladesh: A critical review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalder, B.; Haque, M.M.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Hasan, N.A.; Alam, M.M.; Talukdar, M.M.N.; Shohan, M.H.; Ahasan, N.; Hasan, M.M.; Ahammad, A.K.S. Embryonic and Larval Development of Stinging Catfish, Heteropneustes fossilis, in Relation to Climatic and Water Quality Parameters. Life 2023, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prompatanapak, A.; Lopetcharat, K. Managing changes and risk in seafood supply chain: A case study from Thailand. Aquaculture 2020, 525, 735318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M.; Alam, M.M.; Hoque, M.S.; Hasan, N.A.; Nielsen, M.; Hossain, M.I.; Frederiksen, M. Can Bangladeshi pangasius farmers comply with the requirements of aquaculture certification? Aquac. Rep. 2021, 21, 100811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.J.; Sayeed, M.A.; Akhter, S. Consumers profile analysis towards chicken, beef, mutton, fish and egg consumption in Bangladesh. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2818–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.N.; Islam, A.R.M.T. Consumer fish consumption preferences and contributing factors: Empirical evidence from Rangpur city corporation, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornber, K.; Bashar, A.; Ahmed, M.S.; Bell, A.; Trew, J.; Hasan, M.; Hasan, N.A.; Alam, M.M.; Chaput, D.L.; Haque, M.M.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Aquaculture Environments: Unravelling the Complexity and Connectivity of the Underlying Societal Drivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14891–14903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, K.M.; Belton, B.; Ali, H.; Dhar, G.C.; Ara, I. Aquaculture Technologies in Bangladesh: An Assessment of Technical and Economic Performance and Producer Behavior; Program Report 153; WorldFish: Penang, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.M.; Haque, M.M.; Aziz, M.S.B.; Mondol, M.R. Development of pangasius–carp polyculture in Bangladesh: Understanding farm characteristics by, and association between, socio-economic and biological variables. Aquaculture 2019, 505, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Zou, S. Marketing strategy performance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahiya, E.T. Five decades of research on export barriers: Review and future directions. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1172–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataveli, M.; Ayala, J.C.; Gil, A.J.; Roldán, J.L. An analysis of export barriers for firms in Brazil. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, R.E. Differences in Perceptions of Exporting Problems Based on Firm Size and Export Market Experience. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 28, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfom, G.; Lutz, C. A classification of export marketing problems of small and medium sized manufacturing firms in developing countries. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2006, 1, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfom, G.; Lutz, C.; Ghauri, P. Solving export marketing problems of small and medium-sized firms from developing countries. Afr. J. Bus. 2006, 7, 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, M.H.; Tokol, T.; Harcar, T. The effects of export barriers on perceived export performance: An empirical research on SMEs in Turkey. EuroMed J. Bus. 2007, 2, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Ortiz, J.; Fernandez-Ortiz, R. Why don’t use the same export barrier measurement scale? An empirical analysis in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendy, J.; Rahman, M.; Bal, P.M. Using the “best-fit” approach to investigate the effects of politico-economic and social barriers on SMEs’ internationalization in an emerging country context: Implications and future directions. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 62, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uner, M.M.; Kocak, K.; Cavusgil, E.; Cavusgil, S.T. Do barriers to export vary for born global and across stages of internationalization? An empirical inquiry in the emerging market of Turkey. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkovics, R.R.; Kurt, Y.; Sinkovics, N. The effect of matching on perceived export barriers and performance in an era of globalization discontents: Empirical evidence from UK SMEs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C. An Analysis of the Barriers Hindering Small Business Export Development. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2004, 42, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaum, G.; Strandskov, J.; Derr, E. International Marketing and Export Management, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Harlow, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra, V.; Sarathy, R. International Marketing; Dryden Press: Wilmington, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cateora, P.; Gilly, M.C.; Graham, J. International Marketing; Irwin/McGraw-Hill: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, J.E.; Khorana, S.; Yeung, M.T. Moving beyond least developed country status: Challenges to diversifying Bangladesh’s seafood exports. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2023, 27, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Nielsen, M.; Islam, A.H.M.S. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for quality attributes of farmed fish in Bangladesh: A logit regression and a hedonic price analysis. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2024, 28, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Kabir, K.H.; Roy, D.; Hasan, M.T.; Sarker, M.A.; Dunn, E.S. Understanding the constraints and its related factors in tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) fish culture at farm level: A case from Bangladesh. Aquaculture 2021, 530, 735927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.R.; Haque, M.M.; Razzak, M.A.; Schlüter, L.; Ahsan, E.; Podduturi, R.; Jørgensen, N.O.G. Yellow tainting of flesh in pangasius (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus): Origin of the color and procedures for removal. Aquat. Sci. Eng. 2021, 36, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuzzaman, M.M.; Mozumder, M.M.H.; Mitu, S.J.; Ahamad, A.F.; Bhyuian, M.S. The economic contribution of fish and fish trade in Bangladesh. Aquac. Fish. 2020, 5, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emran, S.J.; Taslim, Q.N.; Taslim, M.A. Standards as trade barriers: The case of shrimp export of Bangladesh of EU. J. Bangladesh Stud. 2015, 17, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, R.; Alam, M.T.; Tasnim, S. Problems and Prospects of Mongla Seaport in Bangladesh. Thoughts Econ. 2022, 32, 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.M.; Rahman, M.A.; Bapary, M.A.J.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Roy, N.C.; Rahman, H.M.M. Prospects and impediments of fish processing plants in north east region of Bangladesh. IJRDO-J. Agric. Res. 2017, 3, 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.; Tomossy, G.F. Overcoming the SPS concerns of the Bangladesh fisheries and aquaculture sector: From compliance to engagement. J. Int. Trade Law Policy 2017, 16, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, I.; Nielsen, M.; Badiuzzaman, B.; Schulze-Ehlers, B. Knowledge transfer from experienced to emerging aquaculture industries in developing countries: The case of shrimp and pangasius in Bangladesh. J. Appl. Aquac. 2020, 33, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.H.; Stachuletz, R.; Nguyen, H.T.H. Export Decision and Credit Constraints under Institution Obstacles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertheussen, B.A.; Dreyer, B.M.; Hermansen, Ø.; Isaksen, J.R. Institutional and financial entry barriers in a fishery. Mar. Policy 2021, 123, 104303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka Tribune. More Cash Incentives for Chilled Fish Exporters Soon. 2022. Available online: https://www.dhakatribune.com/business/275517/more-cash-incentives-for-chilled-fish-exporters (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Mitra, S.; Khan, M.A.; Nielsen, R. Credit constraints and aquaculture productivity. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2019, 23, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Zhong, H.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Tao, M.; Zhang, C.; Gong, D.; Gao, Z.; Tang, C.; et al. Development of fisheries in China. Reprod. Breed. 2021, 1, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oura, M.M.; Zilber, S.N.; Lopes, E.L. Innovation capacity, international experience and export performance of SMEs in Brazil. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.T. Working Conditions, Export Decisions, and Firm Constraints-Evidence from Vietnamese Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotorri, M.; Krasniqi, B.A. Managerial Characteristics and Export Performance–Empirical Evidence from Kosovo. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 13, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, R.M.; Muñoz, A.E.P.; Cai, J. Social and Economic Performance of Tilapia Farming in Brazil; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1181; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. GLOBEFISH Highlights 4th Issue 2022, with Jan.–Jun. 2022 Statistics—International Markets on Fisheries and Aquaculture Products. Quarterly Update; Globefish Highlights No. 4-2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; 65p. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, I.; Nielsen, M.; Schulze-Ehlers, B.; Badiuzzaman, B. Exploring Performance Deficits in the Fish Feed Supply Chain of Bangladesh. Oper. Supply Chain. Manag. 2022, 15, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin, A.F.; Albarki, H.R.; Martin, R.S.H.; Jayanegara, A. Identification of fish meal adulterated with rice bran by using an image analysis method. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; Volume 1241, p. 012138. [Google Scholar]

- Mamun-Ur-Rashid, M.; Belton, B.; Phillips, M.; Rosentrater, K.A. Improving Aquaculture Feed in Bangladesh: From Feed Ingredients to Farmer Profit to Safe Consumption; Working Paper; WorldFish: Penang, Malaysia, 2013; Volume 34, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- ABL (Agrani Bank Limited). Changing Interest Rates of Bank Loan in Different Sectors; Agrani Bank Limited, Head Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bunting, S.W.; Bostock, J.; Leschen, W.; Little, D.C. Evaluating the potential of innovations across aquaculture product value chains for poverty alleviation in Bangladesh and India. Front. Aquac. 2023, 2, 1111266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishamunda, N.; Ridler, N.B.; Bueno, P.G.; Yap, W. Commercial aquaculture in Southeast Asia: Some policy lessons. Food Policy 2009, 34, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, M.A.A.; Qalansawe, A.N.; Nour, A.E.M.; El Basuini, M.F.; Dawood, M.A.O.; Alkahtani, S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. The impact of stocking density and dietary carbon sources on the growth, oxidative status and stress markers of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) reared under biofloc conditions. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 16, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Begum, R.; Nielsen, R.; Hoff, A. Production risk, technical efficiency, and input use nexus: Lessons from Bangladesh aquaculture. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2021, 52, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.T.; Chaijarasphong, T.; Barnes, A.C.; Delamare-Deboutteville, J.; Lee, P.A.; Senapin, S.; Mohan, C.V.; Tang, K.F.J.; McGladdery, S.E.; Bondad-Reantaso, M.G. From the basics to emerging diagnostic technologies: What is on the horizon for tilapia disease diagnostics? Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.G.; Thornber, K.; Chaput, D.L.; Hasan, N.A.; Alam, M.M.; Haque, M.M.; Cable, J.; Temperton, B.; Tyler, C.R. Metagenomic assessment of the diversity and ubiquity of antimicrobial resistance genes in Bangladeshi aquaculture ponds. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 29, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Manyam, S.; Satyanarayana, K.V.; Vijayaraghavan, K. Food Safety System in Bangladesh: Current Status of Food Safety, Scientific Capability, and Industry Preparedness; Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Safety: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2021; 47p. [Google Scholar]

- The Fish Site. Bangladesh Launches Aquaculture Alliance. 2011. Available online: https://thefishsite.com/articles/bangladesh-launches-aquaculture-alliance (accessed on 4 May 2024).

- Jin, C.; Levi, R.; Liang, Q.; Renegar, N.; Zhou, J. Food safety inspection and the adoption of traceability in aquatic wholesale markets: A game-theoretic model and empirical evidence. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 2807–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.T.P.; Saito, Y.; Hoa, N.T.N.; Dan, T.Y.; Matsuishi, T. Pressure–State–Response of traceability implementation in seafood-exporting countries: Evidence from Vietnamese shrimp products. Aquac. Int. 2019, 27, 1209–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R.I.; Narayanan, S.; Belton, B.; Hernandez, R.; Haque, M.M. Shrimp Value Chains in Bangladesh: A Scoping Study of Possible Research Interventions; Initiative Note No. 8; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; 33p. [Google Scholar]

- Mehar, M.; Mekkawy, W.; McDougall, C.; Benzie, J.A.H. Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) trait preferences by women and men farmers in Jessore and Mymensingh districts of Bangladesh. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, A.T.N.; Speelman, S. Understanding vulnerability and resilience of Vietnamese pangasius farming in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aquaculture 2023, 575, 739733. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, N.D.; Tuyen, V.T.X.; Ha, H.T.N.; Dao, D.T.A. Overview: The value chain of Tra catfish in Mekong Delta Region, Vietnam. Vietnam J. Chem. 2023, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.; Bearth, A.; Siegrist, M. How chemophobia affects public acceptance of pesticide use and biotechnology in agriculture. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu-Wu, J.W.F.; Guadamuz-Mayorga, C.; Oviedo-Cerdas, D.; Zamora, W.J. Antibiotic Resistance and Food Safety: Perspectives on New Technologies and Molecules for Microbial Control in the Food Industry. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BTP (Bangladesh Trade Portal). Fish and Fish Product Export Approval License. 2024. Available online: https://bangladeshtradeportal.gov.bd/index.php?r=searchProcedure/view1&id=45 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Amundsen, V.S.; Osmundsen, T.C. Becoming certified, becoming sustainable? Improvements from aquaculture certification schemes as experienced by those certified. Mar. Policy 2020, 119, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, L.; Puertas, R.; García-Álvarez-Coque, J.M. The effects on European importers’ food safety controls in the time of COVID-19. Food Control. 2021, 125, 107952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.G.; Vogl, C.R. Key Performance Characteristics of Organic Shrimp Aquaculture in Southwest Bangladesh. Sustainability 2012, 4, 995–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.M.; Matty, D.; Wim, V. Inclusiveness of consumer access to food safety: Evidence from certified rice in Vietnam. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100491. [Google Scholar]

- Munemo, J. The effect of regulation-driven trade barriers and governance quality on export entrepreneurship. Regul. Gov. 2021, 16, 1119–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnaduwa, U.; Mendis, E.; Kim, S.K. Improvements in Seafood Products through Recent Technological Advancements in Seafood Processing. In Encyclopedia of Marine Biotechnology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 2913–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.L.; Langellotti, A.L.; Torrieri1, E.; Masi, P. Emerging technologies in seafood processing: An overview of innovations reshaping the aquatic food industry. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 23, e13281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, A.R.; Uddin, M.T.; Nielsen, M. Enhancing export potential of Pangasius and Tilapia through quality assurance and safety compliances: Case study of processing plants and exporters in Bangladesh. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderaja, B.M.; Tarigan, N.B.; Verdegem, M.C.J.; Keesman, K.J. Observability-based sensor selection in fish ponds: Application to pond aquaculture in Indonesia. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 98, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atma, Y.; Jusnita, N.; Melanie, S.; Taufik, M.; Yusuf, M. Transforming pangasius Greeefish waste into innovative nano particles: Elevating fish gelatin from derivative to product enhancement. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 26, 100750. [Google Scholar]

- Hasibuan, S.; Syafriadiman, S.; Aryani, N.; Fadhli, M.; Hasibuan, M. The age and quality of pond bottom soil affect water quality and production of Pangasius hypophthalmus in the tropical environment. Aquac. Fish. 2023, 8, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertwanakarn, T.; Purimayata, T.; Luengyosluechakul, T.; Grimalt, P.B.; Pedrazzani, A.S.; Quintiliano, M.H.; Surachetpong, W. Assessment of Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) Welfare in the Semi-Intensive and Intensive Culture Systems in Thailand. Animals 2023, 13, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, P. The early history of freshwater fish production and consumption in Thailand. Front. Aquac. 2023, 2, 1238991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampantamit, T.; Ho, L.; Lachat, C.; Sutummawong, N.; Sorgeloos, P.; Goethals, P. Aquaculture Production and Its Environmental Sustainability in Thailand: Challenges and Potential Solutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podduturi, R.; da Silva David, G.; da Silva, R.J.; Hyldig, G.; Jørgensen, N.O.G.; Petersen, M.A. Characterization and finding the origin of off-flavor compounds in Nile tilapia cultured in net cages in hydroelectric reservoirs, São Paulo State, Brazil. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.; Jayaraman, S.; Sridhar, A.; Venkatasamy, V.; Brown, P.B.; Kari, A.Z.; Tellez-Isaias, G.; Ramasamy, T. Recent Advances in Tilapia Production for Sustainable Developments in Indian Aquaculture and Its Economic Benefits. Fishes 2023, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Jørgensen, N.O.G.; Bass, D.; Santi, M.; Nielsen, M.; Rahman, M.A.; Hasan, N.A.; Bablee, A.L.; Bashar, A.; Hossain, M.I.; et al. Potential of integrated multitrophic aquaculture to make prawn farming sustainable in Bangladesh. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1412919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name of Countries | Production (Million MT) | World Rank Based on Production | Major Species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pangasius | Tilapia | Shrimp | |||

| China | 49.6 | 1st | P | P&E | P&E |

| India | 8.6 | 2nd | P | P | P&E |

| Indonesia | 5.2 | 3rd | P | P&E | P&E |

| Vietnam | 4.6 | 4th | P&E | P&E | P&E |

| Bangladesh | 2.6 | 5th | P | P | P&E |

| Thailand | 0.9 | 10th | P | P | P&E |

| Division-Wise Total Pond Aquaculture Production (Ascending Order) | Division-Wise Top Pond Production District | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Production (MT) | District | Production (MT) | Pangasius Production (MT) | Tilapia Production (MT) | ||

| Khulna | 614,249 |  | → | Mymensingh * | 314,515 | 144,448 | 23,494 |

| Chattogram | 536,951 | → | Cumilla | 227,303 | 46,756 | 41,731 | |

| Mymensingh * | 406,344 | → | Jashore | 196,516 | 14,593 | 21,779 | |

| Rajshahi | 405,005 |  | → | Bogura | 93,084 | 24,501 | 6518 |

| Dhaka | 306,517 |  | → | Dinajpur | 54,294 | 9182 | 7927 |

| Rangpur | 232,155 | → | Barishal | 50,356 | 14,608 | 11,270 | |

| Barishal | 149,285 | → | Gazipur | 36,940 | 2085 | 8019 | |

| Sylhet | 80,564 |  | → | Moulvibazar | 24,402 | 2012 | 7413 |

| Sl. No. | Study About Constraints of Seafood Export from Bangladesh | Aim/Objectives | References | Barriers at Different Levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | External | |||||||

| Company | Product | Industry | Market | Macroenvironment | ||||

| a. | Challenges to diversifying seafood exports. | To examines Bangladesh’s fish and seafood export limits and identifies constraints. | [49] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| b. | Preference for quality attributes in Bangladeshi farmed fish. | To investigate the consumer preferences for farmed fish in Bangladesh. | [50] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| c. | Consumer willingness to pay for quality attributes of farmed pangasius in Bangladesh. | To estimate the implicit price of the quality attributes of pangasius in Bangladesh. | [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| d. | Constraints of tilapia culture at farm level. | To understand and analyze constraints faced by the tilapia fish farmers at farm level in Bangladesh. | [51] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| e. | Prospects and challenges of yellow flesh pangasius in international markets. | To assess yellow discoloration causes in Bangladeshi pangasius fillets, suggest mitigation measures, and evaluate economic viability. | [3] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| f. | Yellow tainting of flesh in pangasius. | To investigate pangasius yellow flesh color reduction. | [52] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| g. | Economic contribution of fish and fish trade. | To show the economic trend regarding the contribution of the fisheries sector. | [53] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| h. | Trade barriers of shrimp export from Bangladesh. | To identify the causes of shrimp export trade barriers. | [54] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| i. | Value chain of pangasius and tilapia. | To develop pangas and tilapia value chain map and estimate the value addition by different actors. | [12] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| j. | Export trend of shrimp and export constraints. | To evaluate the frozen “shrimp” export marketing system, prospect, problems and solutions. | [55] | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| k. | Prospects and impediments of fish processing plants. | To evaluate the problems and prospects of fish processing plants. | [56] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| l. | Export concern of Bangladesh fisheries and aquaculture. | To assess impact of trade barriers on the fisheries and aquaculture sector in Bangladesh. | [57] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Respondent Category | Number of Respondents | Study Methods | Data/Information Gathered |

|---|---|---|---|

| UFOs (Upazila Fisheries Officers) | 3 | Key informant interview | Farmers’ knowledge of international trade, certification, governance, national infrastructure, and communication. |

| FIQC personnel | 2 | Key informant interview | International standard, product quality, market access. |

| Staff of processing plants | 5 | Key informant interview | Industry structure, processing ability, manufacturing product and its quality, skilled and unskilled staff, financial crisis, buyer demand, market knowledge. |

| Personnel/staff of feed mills | 5 | Questionnaire interviews | Feed quality, types of feed, mixture of ingredients, source of ingredients, application of feed rules and regulations. |

| Representative of aqua medicine company | 5 | Questionnaire interviews | Types of medicines, banned/unauthorized medicines, application systems, dosages, farmers’ perception. |

| Aquaculture producers | |||

| 10 (5 pangasius; 5 tilapia) | Questionnaire interviews, FGDs | Production system, good aquaculture practices, financial crisis, international trade knowledge, traceability. |

| 30 (15 pangasius; 15 tilapia) | Questionnaire interviews, FGDs | Production system, export knowledge, and good aquaculture practices. |

| Name of Countries | Production (Million MT) | Export Value (Million USD) | Farming Areas (ha) | No. of Processing Plants | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pangasius | Tilapia | Pangasius | Tilapia | Pangasius | Tilapia | |||

| China | — | 1.66 | — | 872 | — | 133,000 ha | 120 tilapia processing plants. | [16,84,85,86] |

| Vietnam | 1.56 | 0.14 | 2200 | 45 | 5700 | Pond = 30,000 ha; cage = 1.2 million m3 | 100 pangasius processing plants (some factories also used for tilapia). | |

| Indonesia | 0.42 | 1.17 | — | 78.4 | — | — | 10 pangasius processing plants. | |

| Bangladesh | 0.41 | 0.41 | — | — | 43,000 | — | 3 both pangasius and tilapia processing plants. | |

| Thailand | — | 0.21 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Sl. No. | General Areas | Specific Policy/Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| A. | Basic legislation | (a) National fisheries policy, 1998 |

| B. | Accessibility legislation | (a) National land use policy, 2001 (b) Fish and fish products (inspection and quality control) act, 2019 (c) Bangladesh water act, 2013 (d) Bangladesh water development board act, 2000 |

| C. | Environment influence assessment | (a) Environment conservation act, 1995 (b) Environment conservation rules, 1997 (c) Environment court act, 2000 (as amended in 2002) |

| D. | Water and wastewater | (a) Bangladesh water act, 2013 |

| E. | Fish movement | (a) The fisheries quarantine act, 2018 |

| F. | Disease control | (a) Animal disease act, 2005 (b) Animal disease rules, 2008 |

| G. | Drugs and chemicals rules | (a) National drug policy, 2016 |

| H. | Fish feed rules | (a) Fish feed and animal feed act, 2010 (b) Fish feed rules, 2011 |

| I. | Fish hatchery rules | (a) Fish hatchery act, 2010 (b) Fish hatchery rules, 2011 |

| J. | Food safety | (a) Fish and fish product (inspection and quality control) ordinance, 1983 (b) Fish and fish product rules, 1997 |

| K. | Aquaculture investment | (a) Foreign private investment (promotion and protection) act, 1980 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alam, M.M.; Haque, M.M.; Santi, M. Barriers to the Export of Farmed Pangasius and Tilapia from Bangladesh to the International Market: Evidence from Primary and Secondary Data. Aquac. J. 2024, 4, 293-315. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj4040022

Alam MM, Haque MM, Santi M. Barriers to the Export of Farmed Pangasius and Tilapia from Bangladesh to the International Market: Evidence from Primary and Secondary Data. Aquaculture Journal. 2024; 4(4):293-315. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj4040022

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlam, Md. Mehedi, Mohammad Mahfujul Haque, and Morena Santi. 2024. "Barriers to the Export of Farmed Pangasius and Tilapia from Bangladesh to the International Market: Evidence from Primary and Secondary Data" Aquaculture Journal 4, no. 4: 293-315. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj4040022

APA StyleAlam, M. M., Haque, M. M., & Santi, M. (2024). Barriers to the Export of Farmed Pangasius and Tilapia from Bangladesh to the International Market: Evidence from Primary and Secondary Data. Aquaculture Journal, 4(4), 293-315. https://doi.org/10.3390/aquacj4040022