Exploration of Psychosocial Factors in Peruvian Workers: A Quantitative Analysis of Qualitative Categorizations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Questionnaire with Open-Ended Questions

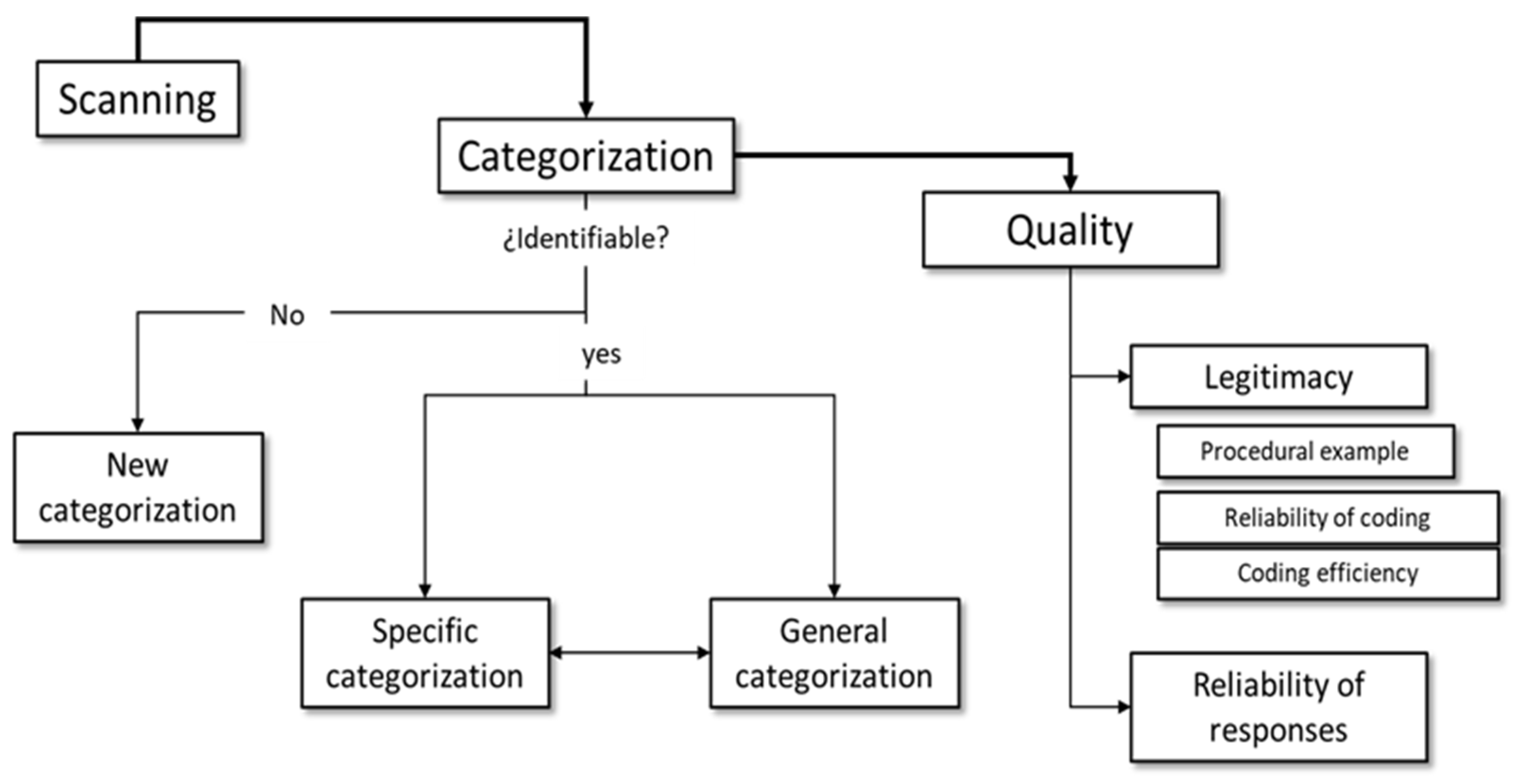

2.2.2. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Coding Efficiency

3.2. Coding Reliability

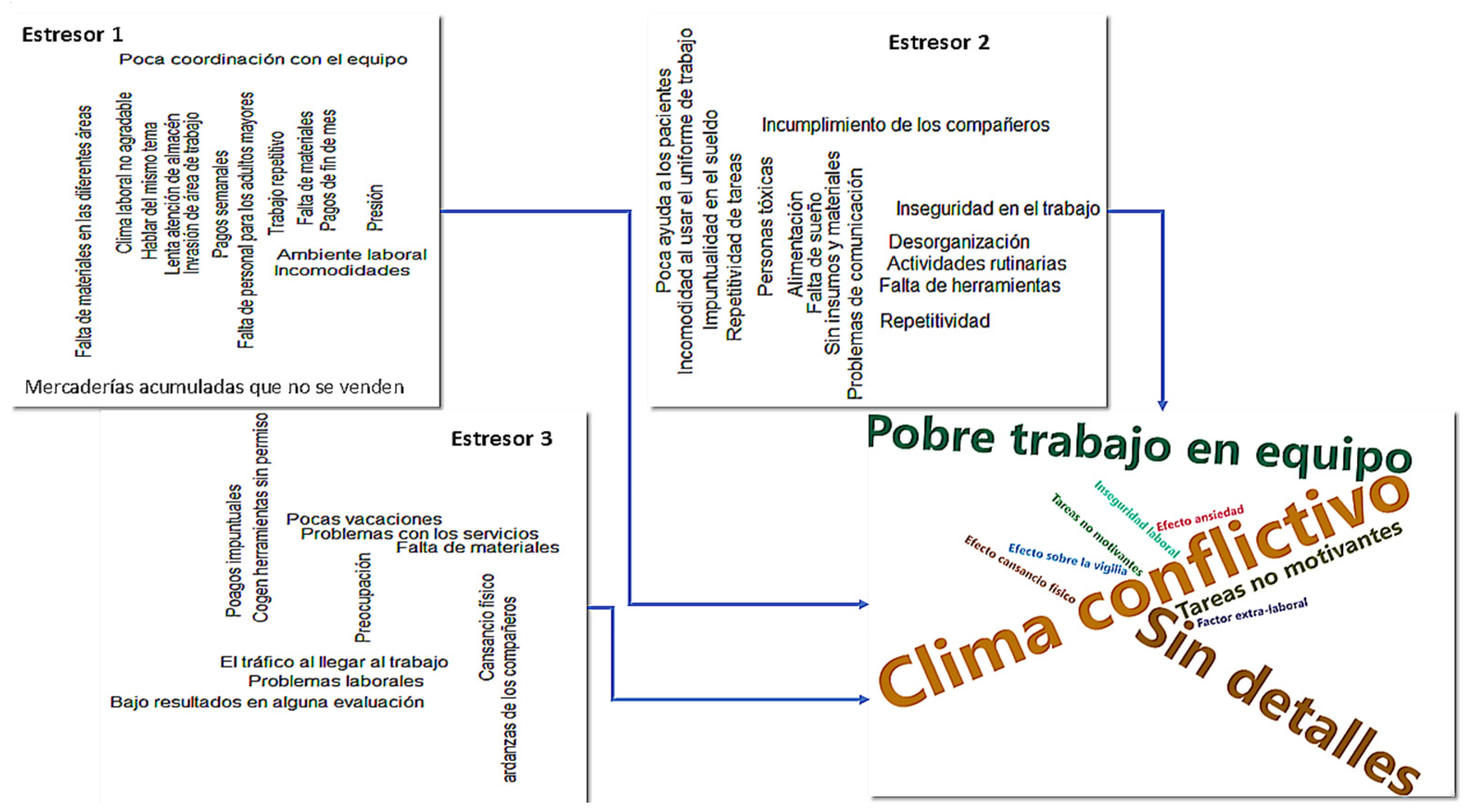

3.3. Categories of Psychosocial Risk Stressors

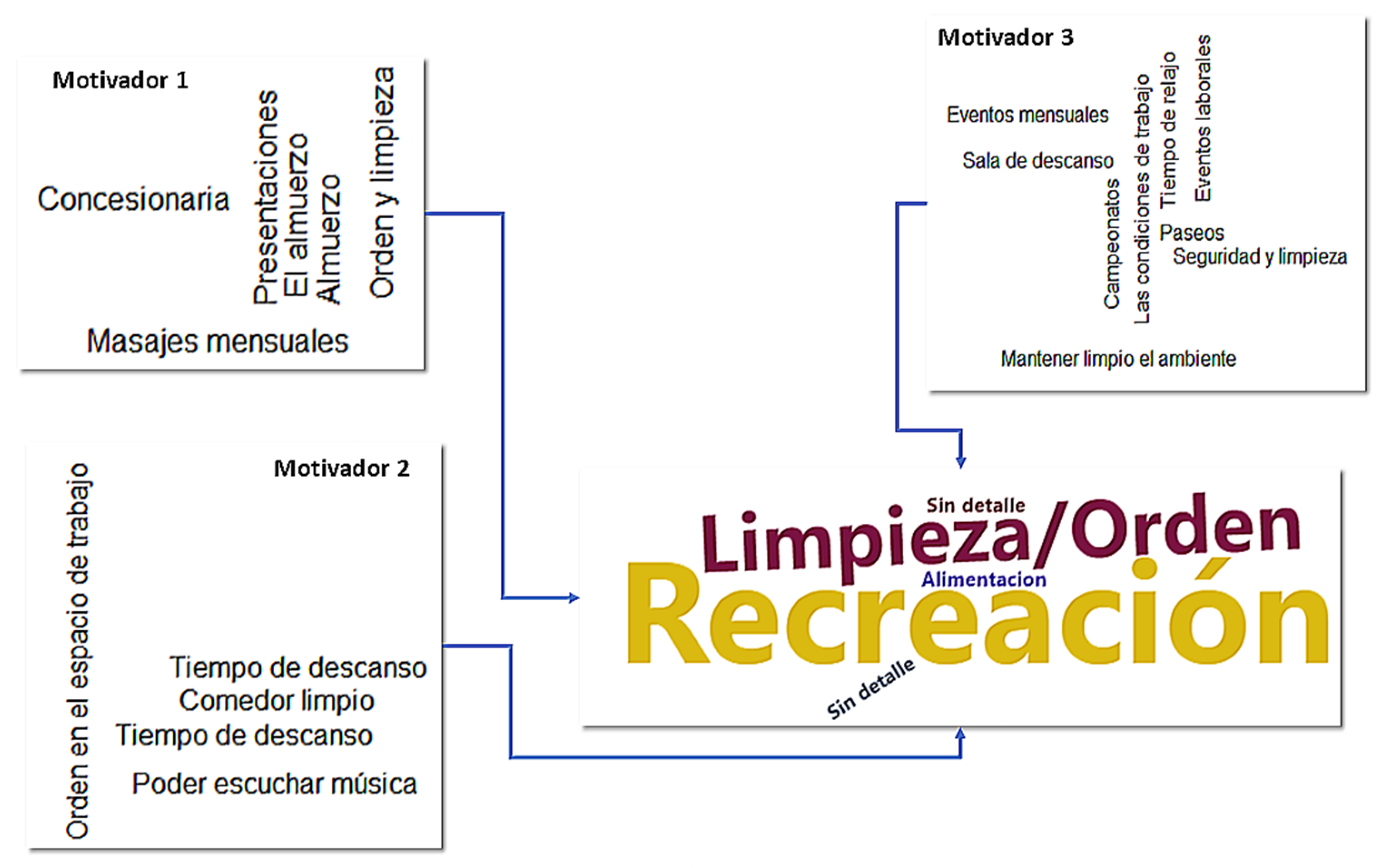

3.4. Categories of Engaging Factors at Work

3.5. Consistency of Responses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Psycho Social Risks and Mental Health (Occupational Hazards in the Health Sector). Available online: https://www.who.int/es/tools/occupational-hazards-in-health-sector/psycho-social-risks-mental-health (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT). El Futuro Del Trabajo: Los Retos Para Los Sindicatos En El Siglo XXI (Informe No. WCMS_553931). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40ed_dialogue/%40actrav/documents/publication/wcms_553931.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Juárez-García, A. Factores Psicosociales Del Trabajo En México: Historia, Conceptos y Perspectivas. In Psicología Organizacional en Latinoamérica; Uribe Prado, F., Ed.; Manual Moderno: Ciudad de México, México, 2018; pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez-García, A.; Flores-Jiménez, C.A. Estructura Factorial de Un Instrumento Para La Evaluación de Procesos Psicosociales En El Trabajo En México. Rev. Psicol. Y Cienc. Comport. Unidad Académica Cienc. Jurídicas Y Soc. 2020, 11, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-García, A.; Camacho-Ávila, A.; García-Rivas, J.; Gutiérrez-Ramos, O. Psychosocial Factors and Mental Health in Mexican Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Salud Ment. 2021, 44, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-García, A.; Flores-Jiménez, C.-A.; Pelcastre-Villafuerte, B.-E. Factores Psicosociales Del Trabajo y Efectos Psicológicos En Comerciantes Informales En Morelos, México: Una Exploración Mixta Preliminar. Rev. Univ. Ind. Santander. Salud 2020, 52, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Soto, C.; Juárez-García, A.; Salinas-Escudero, G.; Toledano-Toledano, F. Item-Level Psychometric Analysis of the Psychosocial Processes at Work Scale (PROPSIT) in Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Jiménez, C.A.; Juárez-García, A. Factores Psicosociales y Síndrome de Burnout En Instructores Comunitarios: Una Aproximación Desde Un Análisis Mixto. Rev. Mex. Sal. Trab. 2016, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez-García, A. Factores Psicosociales, Estrés y Salud En Distintas Ocupaciones: Un Estudio Exploratorio. Investig. En Salud 2007, 9, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez-García, A.; Andrade, P. Redes Semánticas de Trabajo, Salud y Relaciones Interpersonales En El Ámbito Laboral de Diferentes Ocupaciones. Rev. Psicol. Soc. Y Pers. 2004, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. The Job Demands?Resources Model: Challenges for Future Research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Karasek 1979 ASQ—Job Demands Job Redesign. Adm. Sci. Q 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Contributions of Sociology to the Prediction of Heart Disease and Their Implications for Public Health. Eur. J. Public Health 1991, 1, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Imposed Etics, Emics, and Derived Etics: Their Conceptual and Operational Status in Cross-Cultural Psychology. In Emics and Etics: The Insider/Outsider Debate; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, M.; Chalil, G.R.B.; Gupta, A. Emic and Etic: Different Lenses for Research in Culture: Unique Features of Culture in Indian Context. Manag. Labour Stud. 2012, 37, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niblo, D.M.; Jackson, M.S. Model for Combining the Qualitative Emic Approach with the Quantitative Derived Etic Approach. Aust. Psychol. 2004, 39, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Flores, G.; Milbourn, T. Capacidad Evaluativa, Validez Cultural, y Validez Consecuencial En PISA. RELIEVE—Rev. Electrónica De Investig. Y Evaluación Educ. 2016, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO/WHO. Psychosocial Factors at Work: Recognition and Control; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. 196 Health and Wellbeing—Work-Life Imbalance in Developing Countries. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamocuro-Mamani, P. Mental health in the Peruvian population during COVID-19. Cirugía y Cirujanos 2021, 89, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Salud (Perú). Informe Técnico Anual 2024 de Riesgos Psicosociales Laborales En El Perú (Informe No. 6462496). Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/ins/informes-publicaciones/6462496-informe-tecnico-anual-2024-de-riesgos-psicosociales-laborales-en-el-peru (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Paternina, I.L.P.; Pérez, M.L.M.; Villadiego, L.K.H.; Mendoza, M.A. Perspectives and Assessment of Psychosocial Risk in Latin America: A Systemic Review of the Literature. Gac. Med. Caracas 2022, 130, S674–S683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, T.; Smith, A.; Bhakoo, V. Templates in Qualitative Research Methods: Origins, Limitations, and New Directions. Organ. Res. Methods 2022, 25, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C. Qualitative Research in Health Care: Analysing Qualitative Data. BMJ 2000, 320, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bletzer, K.V. Visualizing the Qualitative: Making Sense of Written Comments from an Evaluative Satisfaction Survey. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaught, C.; Lam, P. Using Wordle as a Supplementary Research Tool. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Mendoza, C. Metodología de la Investigación: Las Rutas Cuantitativa, Cualitativa y Mixta; McGraw Hill: Ciudad de México, México, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez-García, A.; Flores-Jiménez, C.A.; Monroy-Castillo, A. Metodología Para la Investigación con IA. Técnica Mixta Para La Investigación Psicosocial (TEMEP), 1st ed.; Terracota, Publicaciones UAEM: Cuernavaca, México, 2025; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey, H. The Second Step in Data Analysis: Coding Qualitative Research Data. J. Soc. Health Diabetes 2015, 03, 007–010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellows, I.; Fellows, M.I.; Rcpp, L.; Rcpp, L. Package ‘Wordcloud’. R Package Version 2018, 2, 331. [Google Scholar]

- Gwet, K.L. Computing Inter-rater Reliability and Its Variance in the Presence of High Agreement. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2008, 61, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (Version 4.4.1) [Computer Software]; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Gwet, K.L. IrrCAC: Computing Chance-Corrected Agreement Coefficients (CAC). R Package Version 2019, 1, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol-Cols, L.; Lazzaro-Salazar, M. Diez Años de Investigación Sobre Riesgos Psicosociales, Salud y Desempeño En América Latina: Una Revisión Sistemática Integradora y Agenda de Investigación. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.S.M.; Chan, V.C.W. Prevalence of Workplace Bullying and Risk Groups in Chinese Employees in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awai, N.S.; Ganasegeran, K.; Abdul Manaf, M.R. Prevalence of Workplace Bullying and Its Associated Factors Among Workers in a Malaysian Public University Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Gutierrez, W.; Taype-Rondan, A.; Bastidas, F.; Casiano-Celestino, R.; Inga-Berrospi, F. Percepción de Médicos Recién Egresados Sobre El Internado Médico En Lima, Perú 2014. Acta Médica Peru. 2016, 33, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverri Chaves, P.; Fernández, I. Analysis of Economic Inequality from a Psychosocial Perspective: The Influence of Cultural Individualism-Collectivism. Rev. Rupturas 2024, 14, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 29 | 60.4 |

| Female | 19 | 39.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 37 | 77.1 |

| Married | 5 | 10.4 |

| Cohabiting | 5 | 10.4 |

| Widowed | 1 | 2.1 |

| Place of birth | ||

| Lima | 33 | 68.8 |

| Outside Lima | 14 | 29.2 |

| No data | 1 | 2.1 |

| Educational level | ||

| Secondary school | 8 | 16.7 |

| Technical (CTE) (<3 years) | 4 | 8.3 |

| Technical (CTE) (3 years) | 19 | 39.6 |

| University | 17 | 35.4 |

| Occupation | ||

| White collar | 12 | 5.76 |

| Manufacturing workers | 21 | 43.75 |

| Customer service workers | 9 | 18.75 |

| Others | 6 | 12.50 |

| M (Md) | SD (Min, Max) | |

| Job seniority | 36.51 (12) | 49.3 (3, 24) |

| Age | 26.5 (25.0) | 7.4 (18, 56) |

| Weekly hours | 49.3 (48) | 15.0 (7, 84) |

| Stressor 1 | Stressor 2 | Stressor 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Efficiency | ||||||

| 3 Immediate | 3 | 6.3 | 36 | 75.0 | 38 | 79.2 |

| 2 Moderate iterative | 26 | 54.2 | 8 | 16.7 | 5 | 10.4 |

| 1 Intense iterative | 17 | 35.4 | 1 | 2.1 | - | - |

| No response | 2 | 4.2 | 3 | 6.3 | 5 | 10.4 |

| Monotonic association a | ||||||

| Stressor 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Stressor 2 | 0.26 ns | - | - | - | - | |

| Stressor 3 | 0.47 ns | 0.53 * | - | - | ||

| Engaging Factor 1 | Engaging Factor 2 | Engaging Factor 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Efficiency | ||||||

| 3 Immediate | 46 | 95.8 | 44 | 91.7 | 44 | 91.7 |

| 2 Moderate iterative | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4.2 | 2 | 4.2 |

| 1 Intense iterative | 1 | 2.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No response | 1 | 2.1 | 2 | 4.2 | 2 | 4.2 |

| Ordinal association a | ||||||

| Engaging factor 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Engaging factor 2 | 1.0 b | - | - | - | - | |

| Engaging factor 3 | 1.0 b | 1.0 | - | - | ||

| Categories | Stressor 1 (n = 46) | Stressor 2 (n = 45) | Stressor 3 (n = 44) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | R | N | % | R | N | % | R | |

| Workload and work pace | 14 | 30.4 | 2 | 8 | 16.7 | 2 | 9 | 20.5 | 2 |

| High responsibility and dangerousness | 1 | 2.2 | 7 | 4 | 8.3 | 5 | 2 | 4.5 | 6 |

| Working hours, shifts or schedules | 4 | 8.7 | 3 | 3 | 6.3 | 6 | 6 | 13.6 | 3 |

| Cognitive demands | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 2 | 4.5 | 6 |

| Emotional (dealing with people) | 4 | 8.7 | 3 | 5 | 10.4 | 3 | 2 | 4.5 | 6 |

| Physical effort | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 1 | 2.1 | 9 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 |

| Physical environment | 4 | 8.7 | 3 | 5 | 10.4 | 3 | 5 | 11.4 | 4 |

| Harassment by supervisors | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 |

| Harassment by colleagues and subordinates | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 |

| Controlling supervision | 4 | 8.7 | 3 | 2 | 4.2 | 7 | 3 | 6.8 | 5 |

| Negative/inadequate feedback from supervisor | 1 | 2.2 | 7 | 2 | 4.2 | 7 | 2 | 4.5 | 6 |

| Unclassifiable (new categories) | 15 | 32.6 | 1 | 15 | 31.3 | 1 | 12 | 27.3 | 1 |

| Distribution | Stressor 1 (n = 46) | Stressor 2 (n = 45) | Stressor 3 (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent (≥10.0%) |

|

|

|

| Somewhat frequent (>0.0%) |

|

|

|

| Infrequent (0.0.%) |

|

|

|

| Categories | Engaging Factor 1 (n = 47) | Engaging Factor 2 (n = 46) | Engaging Factor 3 (n = 46) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Rnk | N | % | Rnk | N | % | Rnk | |||

| Organizational justice | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | ||

| Motivating Salary | 2 | 4.3% | 7 | 3 | 6.5% | 6 | 3 | 6.3% | 6 | ||

| Recognition for work | 2 | 4.3% | 7 | 1 | 2.2% | 9 | 7 | 14.6% | 2 | ||

| Job and professional development opportunities (status) | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 3 | 6.5% | 6 | 2 | 4.2% | 8 | ||

| Job security or stability | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | ||

| Rewarding and meaningful task | 10 | 21.3% | 2 | 6 | 13.0% | 3 | 5 | 10.4% | 4 | ||

| Influence/autonomy at work | 4 | 8.5% | 6 | 5 | 10.9% | 4 | 1 | 2.1% | 9 | ||

| Use of skills at work | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 1 | 2.2% | 9 | 1 | 2.1% | 9 | ||

| Varied work (not monotonous) | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | ||

| Clear functions and roles | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 1 | 2.2% | 9 | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | ||

| Material resources, equipment, and tools | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 1 | 2.2% | 9 | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | ||

| Training and education | 5 | 10.6% | 4 | 2 | 4.3% | 8 | 3 | 6.3% | 6 | ||

| Support from colleagues | 5 | 10.6% | 4 | 9 | 19.6% | 1 | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | ||

| Support from supervisors | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 0 | 0.0% | 13 | 4 | 8.3% | 5 | ||

| Atmosphere of unity | 13 | 27.7% | 1 | 8 | 17.4% | 2 | 7 | 14.6% | 2 | ||

| Unclassifiable (new categories) | 6 | 12.8% | 3 | 5 | 10.4% | 4 | 9 | 18.8% | 1 | ||

| Distribution | Engaging Factor 1 (n = 47) | Engaging Factor 2 (n = 46) | Engaging Factor 3 (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent (≥10.0%) |

|

|

|

| Somewhat frequent (>0.0%) |

|

|

|

| Infrequent (0.0%) |

|

|

|

| Stressors | |||

| Rnk Stressor 1 | Rnk Stressor 2 | Rnk Stressor 3 | |

| Rnk stressor f 1 | 1 | ||

| Rnk stressor f 2 | 0.91 | 1 | |

| Rnk stressor f 3 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 1 |

| Engaging factors | |||

| Rnk engaging f 1 | Rnk engaging f 2 | Rnk engaging f 3 | |

| Rnk engaging f 1 | 1 | ||

| Rnk engaging f 2 | 0.83 | 1 | |

| Rnk engaging f 3 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juárez-García, A.; Merino-Soto, C.; García-Rivas, J. Exploration of Psychosocial Factors in Peruvian Workers: A Quantitative Analysis of Qualitative Categorizations. Hygiene 2025, 5, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5040043

Juárez-García A, Merino-Soto C, García-Rivas J. Exploration of Psychosocial Factors in Peruvian Workers: A Quantitative Analysis of Qualitative Categorizations. Hygiene. 2025; 5(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuárez-García, Arturo, César Merino-Soto, and Javier García-Rivas. 2025. "Exploration of Psychosocial Factors in Peruvian Workers: A Quantitative Analysis of Qualitative Categorizations" Hygiene 5, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5040043

APA StyleJuárez-García, A., Merino-Soto, C., & García-Rivas, J. (2025). Exploration of Psychosocial Factors in Peruvian Workers: A Quantitative Analysis of Qualitative Categorizations. Hygiene, 5(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hygiene5040043