1. Introduction

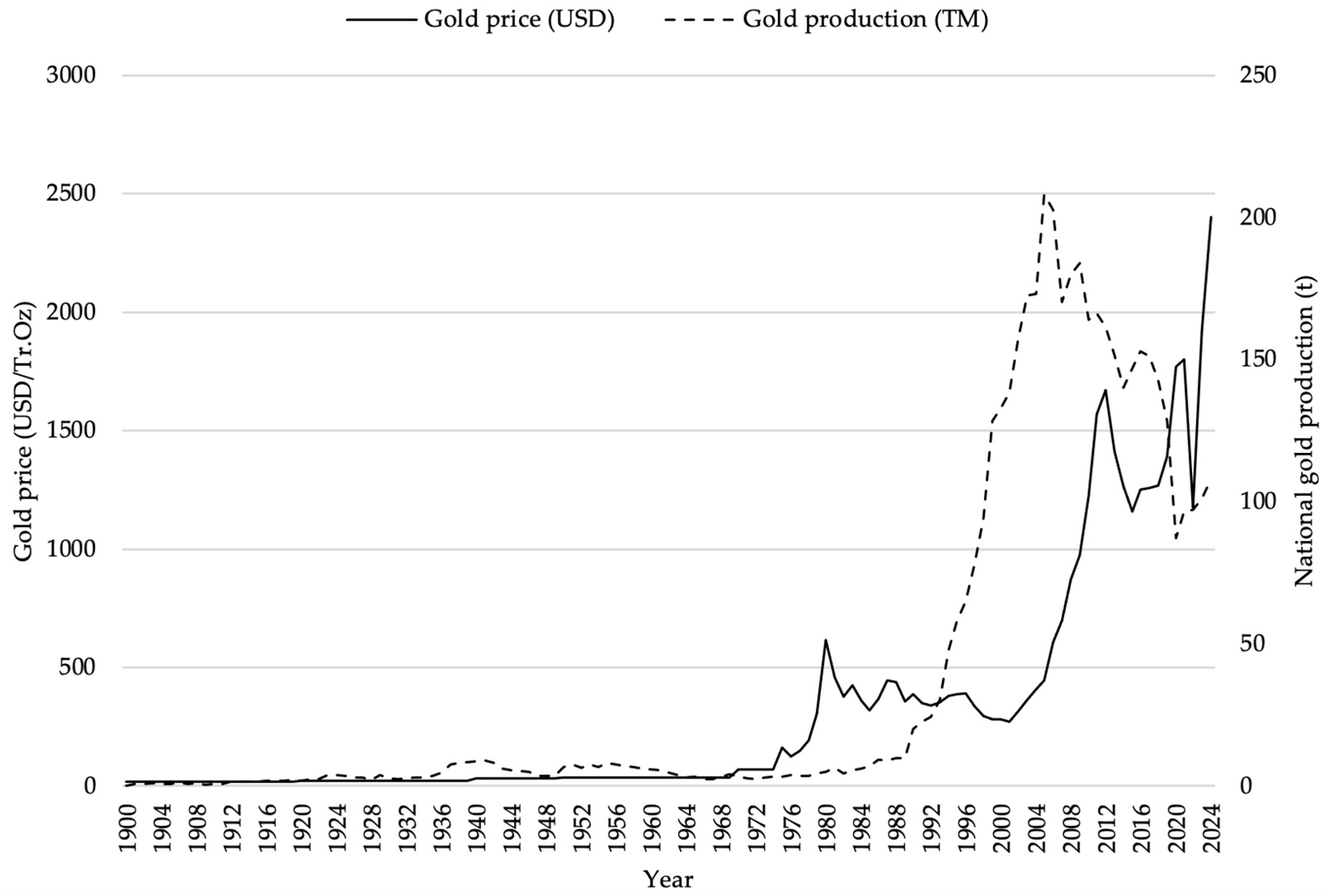

Peru is known for being a country abundant in gold deposits and gold mining operations (

Figure 1). However, despite the country’s long and complex history of gold extraction (from pre-Inca civilizations to the present), there is a notable absence of integrative reviews that synthesize archaeological, historical, legal, and environmental perspectives into a coherent narrative. Existing literature tends to focus on isolated aspects, such as pre-Columbian metallurgy (

Lechtman, 1976;

Aldenderfer et al., 2008), colonial mercury use (

Robins & Hagan, 2012), or contemporary environmental impacts (

Swenson et al., 2011;

Martinez et al., 2018), without connecting these elements across time and territory.

Moreover, the most detailed and context-rich information is often found in Spanish-language sources, including historical studies (

Samamé, 1983a,

1983b), regional mining histories (

Condori, 2010), and government reports (

Vera et al., 2022;

Tumialán, 2003). These sources provide key insights into mining legislation, production data, and sociopolitical dynamics that might be overlooked or underrepresented in English-language publications such as

Brown (

2012),

Gibb and O’Leary (

2014), or

Torres and De la Torre (

2022), among many others. For instance, the evolution of mining codes from 1901 to the present (

Dammert & Molinelli Aristondo, 2007), and the role of the Mining Canon in funding environmental research (e.g.,

Vuono et al., 2021;

Hammer et al., 2023), are rarely discussed outside the Peruvian academic context.

This linguistic gap has contributed to a fragmented understanding of Peru’s mining trajectory in the international literature. As noted by

Manrique and Sanborn (

2021), while environmental issues in the Peruvian Amazon have received attention, broader historical and legal analyses remain underdeveloped, particularly in English-language literature. Likewise, there is a lack of comparative studies examining why Peru has followed a distinct socioeconomic path compared to other mining-based economies with similar colonial legacies, despite sharing common historical starting points (

Palma, 2022;

Saade Hazin, 2022).

By integrating primary and secondary sources in Spanish with international academic literature, this review offers a place-based synthesis that not only fills a critical gap in mining historiography but also challenges dominant narratives; it highlights how gold mining has shaped Peruvian society across centuries and regions, and how local knowledge (often excluded from global discourse) can enrich our understanding of resource extraction and its consequences. Moreover, a place-based synthesis, as used in this review, refers to an integrative analytical approach that emphasizes the spatial, historical, and institutional specificities of gold mining in Peru. Rather than applying generalized models or focusing on isolated themes, this framework draws on diverse sources and disciplinary perspectives to reconstruct how extractive practices have evolved in relation to local ecologies, governance structures, and sociopolitical dynamics. This approach aligns with broader traditions in place-based research, which prioritize contextual, community-rooted, and ecologically grounded understandings of human-environment interactions (

Gruenewald, 2003;

M. E. Smith, 2002). In the case of Peru, it enables a more grounded understanding of gold mining by tracing continuities and ruptures across five historical phases (pre-Inca, Inca, colonial, republican, and contemporary), while also situating these within broader comparative and global contexts.

2. Human History of Gold Mining in Peru

In 2024, Peru’s national gold production experienced sustained growth. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI), the mining and hydrocarbons sector, which includes gold production, recorded a 4.85% annual increase compared to 2023 (

INEI, 2025). This growth was driven by the reactivation of medium- and large-scale mining operations (see

Figure 1), as well as improvements in the formalization of artisanal mining in regions such as Arequipa, La Libertad, and Puno (

MINEM, 2025). Additionally, the metallic mining sector remained stable throughout the year, supported by strong external demand and a gradual recovery in mining investment. Cumulative gold production in 2024 exceeded 100 metric tons, consolidating Peru’s position as one of the leading gold producers in Latin America (

INEI, 2025;

MINEM, 2025). However, in order to understand the country’s gold history, it is necessary to explore the extraction of this precious element since the beginning of human settlements in this territory.

2.1. Pre-Inca Period (Before 1200 CE): Origins of Gold Mining and Local Autonomy

Gold mining in the territory now known as Peru dates back over four millennia. Archaeological evidence from the Lake Titicaca basin reveals gold artifacts dating to around 2000 BCE, making them among the oldest metallurgical findings in the Americas (

Aldenderfer et al., 2008). These early civilizations developed sophisticated techniques for extracting and processing gold, including ore selection, smelting, and alloying (

Lechtman, 1976). Recent studies emphasize that early Andean metallurgy was not only technologically advanced but also deeply embedded in ritual and social practices. Gold was primarily used for symbolic and ceremonial purposes, often found in funerary contexts and elite regalia, rather than for utilitarian or economic exchange (

Roosevelt, 2013). These practices reflect a worldview in which metals were seen as animate substances with spiritual significance.

Mining activities during this period were small-scale and decentralized, often carried out by local communities rather than state-level institutions. However, the emergence of regional trade networks, such as those connecting the Pukina-Collas cultures in southern Peru and northern Chile, suggests increasing social and political complexity. These networks facilitated the exchange of gold, silver, copper, and other goods, laying the groundwork for the more centralized systems of the Inca period, but making different cultures exchange gold for other products (

Figure 2).

In the Amazon basin, archaeological and ethnohistorical research suggests that indigenous groups such as the Chachapoya and Huambisa engaged in small-scale gold extraction from alluvial deposits. These operations likely used simple techniques like panning and sluicing, adapted to the dense rainforest environment (

Roosevelt, 2013). Although less extensive than Andean mining, Amazonian gold held significant cultural value, often associated with burial rites and social status. Additionally, geological studies have shown that natural processes such as colloidal transport and flocculation contributed to the hyper-enrichment of gold in certain Peruvian Andean deposits, which may have facilitated early mining activities (

McLeish et al., 2021). Also, the tectonic and magmatic evolution of the Peruvian Andes created favorable conditions for orogenic gold formation, particularly in regions later exploited by pre-Inca societies (

Goldfarb & Pitcairn, 2023).

In summary, the pre-Inca period established the technological, symbolic, and territorial foundations of gold mining in Peru. These early practices were not merely precursors to Inca statecraft but complex systems in their own right, shaped by local ecologies and ethnicities. Understanding this period is essential for tracing the continuities and ruptures that define Peru’s long mining history.

2.2. Inca Period: State Centralization, Sacred Gold, and Institutional Continuities

The Inca Empire (also known as Tahuantinsuyu), which emerged in the 13th century and expanded rapidly under Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui in the 15th century, marked a turning point in the political and economic organization of gold mining in the Peruvian Andes (

Macquarrie, 2008). Unlike the decentralized and small-scale mining practices of pre-Inca societies, the Inca developed a highly centralized system of resource extraction, in which the state exerted direct control over mineral wealth and labor (

Espinoza, 1995;

Bray, 1991).

Gold was not used as currency but held immense symbolic and religious value. It was considered the “sweat of the sun” and was used to adorn temples, royal palaces, and ceremonial objects dedicated to Inti, the sun god (

Lechtman, 1984;

Maccormack, 1989). The Qoricancha temple in Cusco, for instance, was covered in sheets of gold and housed golden effigies, reflecting the divine association of the metal (

Caley, 1977).

The Inca state organized mining through the

mita system, a form of rotational labor taxation that mobilized thousands of workers for state projects, including mining and metallurgy (

Espinoza, 1995). Raw materials were extracted from mines across the empire and transported to state-controlled workshops near Cusco, where specialized artisans (

amautas) crafted ceremonial and elite objects (

Bray, 1991). This centralized production system ensured that gold remained a tool of political integration and religious legitimacy.

Technologically, the Incas employed gravity separation, smelting in wind-powered furnaces known as

huayras or

huayrachinas (

Figure 3), and possibly mercury amalgamation, although the latter remains debated (

Brooks, 2023). They also practiced alluvial gold extraction using sieves and pans, with toponyms such as

cori-huayrachina (“place where gold is extracted”) attesting to the widespread nature of these practices (

Regal, 1946).

Recent metallurgical analyses of Inca gold artifacts reveal consistent alloying with silver, typically ranging from 20% to 30%, suggesting intentional compositional control for aesthetic or symbolic purposes (

Vera et al., 2022;

Lechtman et al., 1982). These findings underscore the Incas’ advanced understanding of metallurgy and their ability to manipulate material properties for cultural purposes.

The Inca period thus represents a consolidation of earlier mining traditions into a state-directed system that fused economic, religious, and political functions. This institutional legacy (particularly the use of mining for state-building and elite legitimation) would persist into the Colonial period, albeit under radically different power structures.

2.3. Colonial Period: Imperial Extraction, Institutional Reconfiguration, and Enduring Inequalities

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire in the 16th century marked a profound transformation in the organization of gold mining in Peru. While the Inca had centralized mining under State control for religious and political purposes, the Spanish Colonial regime reoriented gold extraction toward imperial accumulation, embedding it within a transatlantic economic system (

Robins & Hagan, 2012). This shift entailed not only a change in ownership but also in the logic of extraction, from sacred stewardship to commercial exploitation.

Colonial authorities appropriated Inca mines and expanded operations across the Andes, introducing new legal and labor institutions. The Ordinances of Mining (Ordenanzas de Minería), ratified in 1575, formalized property rights and taxation mechanisms that favored Spanish elites and the Crown (

Dammert & Molinelli Aristondo, 2007). These ordinances institutionalized the Inca-originated mita system (see

Section 2.2) as a coercive labor regime that conscripted indigenous populations into hazardous mining work, often under brutal conditions (

Robins, 2011).

Although silver-dominated Colonial mining, gold remained significant, particularly in regions like Lucanas, Carabaya, and Cajamarca. Between 1533 and 1821, Peru produced an estimated 4.8 million ounces of gold (

Acosta, 2014). Much of this production relied on mercury amalgamation, a technique that intensified after the discovery of the Huancavelica mercury mine in 1564. The environmental and health consequences were catastrophic: mercury vapor emissions from Huancavelica and Potosí accounted for nearly 25% of Latin America’s total during the Colonial period, contributing to widespread poisoning and death (

Robins & Hagan, 2012;

Nriagu, 1993).

The Colonial mining economy also reshaped regional geographies. In Arequipa, for example, the discovery of the Caylloma deposits in the 17th century transformed an agrarian province into a mining hub, with the establishment of royal treasuries (cajas reales) to collect taxes on extracted metals (

Condori, 2010). Yet, this wealth rarely translated into local development. Instead, it flowed to Lima and ultimately to Spain, reinforcing a pattern of resource extraction without reinvestment that continues to characterize Peru’s mining regions today.

Importantly, the Colonial period laid the groundwork for enduring institutional asymmetries. The legal frameworks, labor systems, and extractive logics established under Spanish rule persisted (albeit in modified forms) into the Republican era. As scholars have noted, the Colonial legacy of centralized control, racialized labor (in the form of indigenous workers), and environmental disregard continued to shape Peru’s mining sector and its uneven development outcomes (

Brown, 2012;

Thorp & Bertram, 1985).

In summary, the Colonial period was not merely a phase of intensified extraction but a moment of institutional reconfiguration. It embedded gold mining within global circuits of capital, redefined the relationship between State, labor, and land, and established patterns of inequality that remain visible in contemporary mining towns. Understanding this legacy is essential for any serious analysis of Peru’s current challenges in mining governance, environmental justice, and regional development.

2.4. Republican Period: Institutional Inertia, Resource Nationalism, and Uneven Development

The transition from Colonial rule to Republican governance did not dismantle the extractive institutions established under Spanish imperialism in Peru. Instead, the early Republic inherited a mining sector in crisis and disrupted by war, looting, and the collapse of Colonial labor systems, though it retained many of its legal and territorial logics (

Contreras Carranza, 2010;

Díaz Palacios & Arana Cardó, 2016). Mining laws continued to reflect the Spanish Indian Laws (Leyes de Indias) well into the 19th century, and the state struggled to assert control over mineral wealth in a fragmented post-independence landscape (

Dammert & Molinelli Aristondo, 2007).

Despite these challenges, the 19th century saw efforts to revive gold mining through foreign investment and legal reforms. British and French companies were granted concessions, and new foundries were established in Arequipa and Tacna (

Condori, 2010). A short-lived gold rush in the 1820s and 1830s in southern Peru (particularly in Huayllura) attracted thousands of migrants, but the boom quickly faded due to poor infrastructure and lack of state support (

Acosta, 2014). Indeed, a few milestones can provide an idea of how this period unfolded in the early Republican period, with a focus on the Arequipa Region (

Condori, 2010): (1820–1824) Demonstration of gold mining activity in Arequipa, after the creation of a company whose intention was to exploit gold and silver in the traditional town of Huasacache and the town of Congata; (1825) Formalization of a company with the intention of mining two gold veins in the Palca valley. During these years, the foundry house operated in Arequipa, where the extracted metals were processed and taxes were paid; (1827–1840) Arequipa experienced “The Arequipa gold fever” due to the Discovery of the Huayllura, mining site, located in the Province of La Unión. The most important mine was Copacabana, which produced PEN 600,000; and (1840) gold wealth was exhausted.

The promulgation of the Mining Code (Código de Minas) in 1901 marked a turning point. It declared mining rights perpetual and irrevocable, incentivizing private investment and formalizing property regimes (

Tumialán, 2003). However, this legal modernization did not translate into equitable development. Mining remained concentrated in enclaves with minimal reinvestment in local infrastructure, education, or health; patterns that persist in towns like Chala, where basic services remain deficient despite decades of gold extraction (

Saade Hazin, 2022).

Throughout the 20th century, Peru oscillated between resource nationalism and liberalization. The State nationalized key sectors in the 1970s, only to reverse course in the 1990s with neoliberal reforms that opened the sector to foreign capital (

Thorp & Bertram, 1985). These shifts produced cycles of boom and bust, but failed to address the structural inequalities embedded in the mining economy. As scholars have noted, the persistence of informal and illegal mining, especially in the Amazon and Andean regions, reflects both weak State capacity and the exclusionary nature of formal mining regimes (

Díaz Palacios & Arana Cardó, 2016;

Verbrugge & Besamanos, 2016;

N. M. Smith, 2019).

The Republican period thus represents a continuum of institutional inertia and selective reform. While legal frameworks evolved, the underlying model of extraction without redistribution remained largely intact. This helps explain why Peru, despite being one of the world’s top gold producers, continues to exhibit stark regional disparities and limited infrastructure in mining zones. The legacy of the Republic is not merely one of legal change, but of missed opportunities to transform mineral wealth into inclusive development.

2.5. Gold Mining in Peru After 1900: Sustainability, Informality, and Global Context

As previously mentioned, the enactment of Peru’s Mining Code in 1901 marked a pivotal moment in the country’s gold mining history. By granting perpetual and irrevocable rights to legally acquired mining concessions and exempting machinery and inputs from customs duties, the Code laid the foundation for a century of intensified extraction (

Tumialán, 2003). However, the evolution of gold mining in Peru since then continued to be shaped not only by legal reforms and market dynamics, but also by growing concerns over sustainability, informality, and social conflicts.

Gold production remained modest until the mid-20th century, constrained by low international prices and limited investment (

Figure 4). The Bretton Woods Agreement (1944–1971), which fixed the gold price at USD 35 per ounce, further discouraged exploration (

Reyes Konings, 2010). It was not until the liberalization reforms of the 1990s (particularly the privatization of State-owned enterprises and the promotion of foreign investment) that a mining boom occurred. Projects such as Yanacocha (Cajamarca) and Pierina (Áncash) positioned Peru as Latin America’s leading gold producer by the early 2000s (

Acosta, 2014).

Moreover, according to data from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Peru’s gold production was approximately 97 t in 2022 and is estimated at around 100 t for 2023–2024 (

USGS, 2024). In contrast, the world’s largest producers in 2024 accounted for a significant portion of global production, which that year totaled approximately 3300 t, led by China (~380 t), Russia (~310 t), Australia (~290 t), Canada (~200 t), and the United States (~160 t) (

USGS, 2025). Therefore, although Peru is among the world’s major producers, its output represents only a modest fraction compared to that of the major mining countries. However, Peru ranks second in Latin America, surpassed only by Mexico with approximately 130 t in 2024, and followed by Brazil (~70 t), Colombia (~67 t), and Argentina (~43 t). These figures are derived from combinations of national databases and international reports (USGS/national bulletins/data services) and may vary depending on the revision and the inclusion/exclusion of informal production (

CEIC, 2025;

MINEM, 2024,

2025). It is important to note that these figures are approximations because (1) different sources use different methodologies and cut-off dates, and (2) artisanal/illegal production (highly relevant in several countries such as Peru) is not always accounted for homogeneously; therefore, the rankings may change slightly depending on the source.

Moreover, informal and illegal gold mining has expanded dramatically since the 1980s, particularly in Madre de Dios, Puno, and Arequipa. The persistence of informality is linked to bureaucratic hurdles, lack of incentives, and weak State presence in mining zones, not mentioning environmental issues (see

Section 3). In regions like Secocha (Arequipa), informal mining has become the main livelihood, often controlled by local elites or criminal networks. This mirrors trends in other Latin American countries, such as Colombia and Venezuela, where over 80% of gold production is estimated to be illegal (

Maus & Werner, 2024;

Alejo Zapata et al., 2023).

Compared to countries like Chile or Australia, Peru’s gold sector is more fragmented and socially contentious. While Chile has focused on copper and implemented stricter environmental regulations, Peru’s gold sector remains marked by duality: a modern, export-oriented formal sector and a vast informal economy (

Verbrugge & Besamanos, 2016). Moreover, the global mining industry is under pressure to align with sustainability goals and the energy transition. Countries such as Canada and Finland are investing in “green mining” technologies and circular economy models (

Maus & Werner, 2024). In Peru, however, although some companies have adopted cleaner technologies such as cyanide recovery systems (

Hammer et al., 2023), widespread adoption is limited by cost and regulatory gaps.

Between 2023 and 2025, Peru’s gold production has shown signs of stabilization after the COVID-19 downturn. However, social conflicts (especially in Cajamarca and La Libertad) continue to disrupt operations (

Palma, 2022) (

Figure 5). The government has announced new initiatives to strengthen environmental monitoring and expand formalization, but implementation remains a challenge (

Giraldo Malca et al., 2023). At the same time, international scrutiny is increasing; global investors and certification schemes (e.g., OECD Due Diligence Guidance, Fairmined) are demanding greater transparency and sustainability from gold producers, presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for Peru to modernize its gold sector and reduce its environmental and social footprint.

3. Legal and Environmental Aspects of Gold Mining in Peru

Building on the historical legacies discussed in the previous section, gold mining in Peru operates within a complex legal and environmental framework shaped by historical legacies, neoliberal reforms, and contemporary sustainability challenges. While the country has made progress in regulating formal mining and promoting environmental standards, significant gaps remain, particularly in addressing mercury pollution, illegal mining, and weak enforcement in ecologically sensitive regions. Modern formal mining in Peru can be classified according to productive capacities, as detailed in

Table 1.

Peru’s mining legislation has evolved significantly since the early 20th century. The 1901 Mining Code granted perpetual rights to legally acquired concessions, encouraging private investment (

Tumialán, 2003). Later reforms, such as the 1950 and 1971 Mining Codes, increased State control over subsoil resources. The 1991 General Mining Law marked a return to liberalization, allowing full private ownership of extracted minerals and promoting foreign investment (

Dammert & Molinelli Aristondo, 2007) (

Table 2).

To address the proliferation of informal and illegal mining, Legislative Decree No. 1105 (

MINAM, 2012) established a framework for the formalization of artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM). However, implementation has been slow and uneven. As of 2023, there were approximately 200,000 informal (illegal) miners, of whom 87,771 were registered with REINFO (Comprehensive Registry of Mining Formalization). Of these, only 25,087 were completing the formalization process, while the rest (71%) suspended the process (

PERUMIN, 2023).

Environmental degradation is a major concern in both formal and informal mining operations. In Peru, large-scale mining has driven deforestation, water contamination, and biodiversity loss, particularly in the Amazon basin (

Swenson et al., 2011). However, artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) is especially harmful, representing the largest global source of mercury emissions, i.e., 37% of global anthropogenic mercury pollution (

Aldous et al., 2024). Moreover, Peru is one of the top mercury polluters: in 2021, five countries (China, India, Indonesia, Peru, and Brazil) together accounted for around half of global anthropogenic mercury emissions, being Peru responsible for around 7% of global emissions (

Tamayo et al., 2017;

Qiu et al., 2025). Mercury is widely used in ASGM to amalgamate gold, often without protective measures or waste management, resulting in severe contamination of rivers, groundwater, soils, and food chains in the Amazon and Andean regions (

Gerson et al., 2022;

Echave, 2016).

Although formal mining is subject to environmental impact assessments, enforcement is weak, particularly in remote areas. However, ASGM is the main source of pollution, as it frequently operates outside legal frameworks. This reflects broader shortcomings in Peru’s environmental governance, which remains fragmented (

Alejo Zapata et al., 2023). At the global level, more than half of mining areas lack adequate documentation of their environmental and social impacts, hindering the monitoring of sustainability outcomes (

Maus & Werner, 2024).

A 2024 global review emphasized that mercury contamination from ASGM is not only an environmental issue but also a human rights and public health crisis. The ingestion of mercury affects neurological, reproductive, and cognitive systems, especially among indigenous and rural populations. Scientists recommend that countries like Peru adopt “theories of change” to design more effective, context-specific interventions that integrate legal, institutional, and community-based approaches (

Aldous et al., 2024).

Efforts to formalize ASM in Peru have faced structural challenges. Many miners view the process as bureaucratic, expensive, and offering few tangible benefits. Moreover, overlapping land rights, limited institutional coordination, and weak State presence in mining zones have fueled social tensions and violent conflicts (

Giraldo Malca et al., 2023).

Although Peru is a signatory to the Minamata Convention on Mercury, enforcement of mercury-related regulations remains inconsistent. Coordination among government agencies is limited, and environmental monitoring is often underfunded or absent in remote areas (

Aldous et al., 2024), as previously mentioned. Therefore, a more integrated governance model that combines legal reform, environmental science, and community engagement, is urgently needed to address the root causes of informality and environmental degradation.

4. Comparative Analysis and Synthesis

Peru’s gold mining sector presents a unique case within the global mining landscape. While the country is among the top gold producers worldwide, it continues to face persistent challenges related to informality, environmental degradation, and weak governance. A comparative analysis with other mining-intensive countries such as Chile, Ghana, and South Africa reveals both structural differences and shared vulnerabilities that help contextualize Peru’s current trajectory.

Unlike Chile, which has developed a centralized and technically robust mining governance system focused on copper, Peru’s regulatory framework for gold mining remains fragmented and reactive. Chile’s National Geology and Mining Service (SERNAGEOMIN) plays a key role in enforcing environmental and safety standards, while Peru’s oversight is divided among multiple agencies with overlapping mandates and limited enforcement capacity (

Maus & Werner, 2024).

In Ghana and South Africa, formalization of ASM has been more systematically integrated into national development strategies. Ghana, for instance, has implemented community mining schemes and mobile mercury-free processing units (

MESTI, 2019), while South Africa has piloted ASM cooperatives with technical support (

Mutemeri & Petersen, 2020). In contrast, Peru’s formalization efforts have been hindered by bureaucratic complexity, limited incentives, and weak local governance (

Aldous et al., 2024). To provide a comparative perspective,

Table 3 summarizes key characteristics of the gold mining sector in four countries with significant extractive trajectories: Peru, Chile, Ghana, and South Africa. The comparison focuses on four critical dimensions: formalization of ASM, environmental regulation, investment in green technologies, and reinvestment in local infrastructure. This cross-national analysis highlights structural gaps in Peru’s mining governance and identifies potential policy lessons from international experiences.

Environmental degradation from gold mining is a shared concern across the Global South. In Peru, mercury contamination from ASM remains a critical issue, particularly in the Amazon basin. Similar patterns are observed in Ghana’s Western Region and South Africa’s Witwatersrand Basin, where abandoned mines and informal operations contribute to water and soil pollution (

Marrugo Negrete et al., 2025).

However, Peru’s environmental monitoring systems are less developed than those in countries like Chile or South Africa, which have invested in satellite-based surveillance and real-time water quality monitoring (

Maus & Werner, 2024;

Adom & Simatele, 2025). Moreover, Peru lacks a comprehensive inventory of mine sites and their environmental footprints, an issue that affects over half of the world’s mining areas and hampers global efforts to track sustainability outcomes (

Maus & Werner, 2024).

Despite its mineral wealth, Peru continues to struggle with basic infrastructure deficits in mining regions, including access to clean water, sanitation, and healthcare. This contrasts with countries like Chile and South Africa, where mining revenues have been more effectively channeled into public infrastructure and social services. The persistence of poverty and inequality in Peruvian mining towns such as Chala or La Rinconada underscores the limited trickle-down effects of gold extraction (

Palma, 2022).

This divergence raises important questions about the historical and institutional roots of Peru’s development path. While Colonial legacies and neoliberal reforms have shaped mining governance across Latin America and Africa, Peru’s combination of weak State capacity, fragmented regulations, and social exclusion has produced a particularly unstable and unequal mining economy.

This comparative perspective reinforces the value of a place-based synthesis that integrates historical, legal, environmental, and social dimensions. Rather than treating Peru’s mining history as a linear narrative, this approach highlights the spatial and institutional specificities that differentiate it from other mining economies. It also underscores the need for interdisciplinary research that bridges archaeology, environmental science, legal studies, and development economics to better understand the long-term impacts of gold mining in Peru and beyond.

Historical Roots of Contemporary Mining Challenges

Based on the previous sections, several of the contemporary challenges observed in Peru’s gold-mining sector reflect longstanding historical patterns that began in pre-Inca, Inca, and Colonial times. Pre-Inca decentralized and community-based extraction practices resonate today in the persistence of small-scale and informal mining, often operating outside state oversight. The Inca model of centralized resource control and reliance on rotational labor systems introduced enduring tensions between local communities and central authorities (tensions still visible in present conflicts over land use, taxation, and environmental governance). Colonial institutions further entrenched unequal labor relations, weak local reinvestment, and extractive logics oriented toward external markets rather than regional development.

These structural continuities help explain why current problems such as informality, environmental degradation, and uneven regional development remain difficult to resolve. Peru’s modern gold-mining landscape is therefore not only shaped by recent reforms but also by deep historical trajectories that continue to influence governance, social dynamics, and environmental outcomes.

5. Gold Mining and Peru’s Strategic Role in the Energy Transition

As the global economy accelerates its shift toward decarbonization, the mining sector is undergoing a profound transformation. While much of the attention has focused on critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements, gold also plays a strategic (though often overlooked) role in the energy transition. In Peru, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity: how to align gold mining with sustainability goals while addressing the sector’s historical and environmental legacies.

Gold is essential to the development of clean energy technologies, particularly in electronics, photovoltaics, and hydrogen fuel cells. Its high conductivity, corrosion resistance, and catalytic properties make it a key component in low-carbon technologies and advanced manufacturing systems (

Trench et al., 2024). Moreover, gold is increasingly used in green finance instruments such as ESG-compliant reserves and climate-linked investment portfolios, reinforcing its relevance in sustainable economic systems.

Peru remains one of the world’s top gold producers, yet its mining sector is still dominated by conventional extraction methods and limited value-added processing. Unlike countries such as Canada or Finland, which are investing in green mining technologies and circular economy models, Peru has yet to fully integrate sustainability into its gold value chain (

Maus & Werner, 2024).

Recent reviews highlight the potential for Peru to recover gold and other valuable metals from mine tailings using advanced hydrometallurgical techniques. These innovations not only reduce environmental risks but also support resource efficiency and supply chain resilience, being those key pillars of the energy transition (

Trench et al., 2024).

Despite its mineral wealth, Peru lacks a national strategy that explicitly links gold mining to the energy transition, with domestic policies remaining fragmented. There is no dedicated roadmap for decarbonizing the mining sector or incentivizing the adoption of clean technologies in gold extraction (

Maus & Werner, 2024).

However, recent developments suggest a shift in discourse. In 2024, Peru signed a memorandum of understanding with the United States to promote sustainable mining practices and attract investment in critical mineral supply chains. Although gold was not the primary focus, the agreement opens the door for broader reforms that could include gold within a sustainability framework (

Trench et al., 2024).

A just energy transition requires not only technological innovation but also social inclusion and environmental justice. In Peru, governance aspects of a just energy transition are closely linked to corporate disclosure in the mining sector. Publicly listed mining companies are required by the Superintendency of the Securities Market (Superintendencia del Mercado de Valores, SMV) to publish an annual Corporate Sustainability Report under Resolution 033-2015-SMV/01 and its 2020 update (

SMV, 2015,

2020). In addition, all mining operators (listed or not) must comply with environmental and social reporting obligations established under the national environmental impact assessment system (SEIA), including EIAs and monitoring duties (

MINAM, 2020). Many large mining companies also follow international reporting frameworks such as GRI, ICMM principles, and EITI standards, which further structure ESG disclosure in the sector (e.g.,

GRI, 2023;

Gold Fields, 2025). In Peru, this means addressing the legacy of informal and illegal gold mining, which continues to harm ecosystems and marginalize communities. Formalizing these operations, improving environmental monitoring, and reinvesting mining revenues into local infrastructure are essential steps toward aligning gold mining with the principles of a just transition (

Maus & Werner, 2024).

Ultimately, Peru’s gold sector must evolve from a purely extractive model to one that supports long-term sustainability, both nationally and globally. This requires coordinated action across government, industry, and civil society, as well as a renewed commitment to integrating gold into the broader narrative of climate resilience and green development.

6. Conclusions

This review has presented a place-based synthesis of gold mining in Peru, tracing its evolution from pre-Inca metallurgy to contemporary challenges of sustainability, informality, and governance. By integrating historical, legal, environmental, and comparative perspectives, the paper offers a multidimensional understanding of how gold mining has shaped, and been shaped by, Peruvian society across time and space.

The analysis reveals that Peru’s gold sector is marked by deep structural contradictions: it is a global leader in production, yet struggles with informality, environmental degradation, and weak institutional capacity. Unlike countries such as Chile, Ghana, or South Africa, Peru has not fully integrated gold mining into a national development strategy aligned with sustainability and the energy transition. The persistence of illegal gold mining, mercury pollution, and social conflicts underscores the urgent need for a more coherent and inclusive governance model.

This review also highlights the value of incorporating Spanish-language sources and local knowledge systems into the global gold mining literature. Much of the nuanced understanding of Peru’s gold mining history, legal reforms, and regional dynamics remains underrepresented in English-language publications. By bridging this gap, the paper contributes to a more plural and grounded historiography of extractive industries.

Many current challenges in Peru’s gold-mining sector have deep historical roots. Pre-Inca decentralized extraction echoes today in the persistence of informal mining, while Inca-era centralized control created enduring tensions between communities and the state. Colonial mining further reinforced extractive institutions and weak environmental oversight. Together, these legacies help explain the persistence of informality, environmental degradation, and governance conflicts in modern Peru.

Finally, the concept of a place-based synthesis proves useful in articulating the spatial and institutional specificities of Peru’s mining trajectory. It allows for a more holistic and critical reflection on the legacies of colonialism, the impacts of neoliberal reforms, and the possibilities for a just transition. Moving forward, interdisciplinary research and policy innovation will be essential to ensure that gold mining in Peru contributes not only to economic growth but also to environmental sustainability and social equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z., C.Z. and F.A.; methodology, J.Z., P.A.G.-C. and D.C.V.; formal analysis, J.Z., C.Z., M.G., F.A. and E.Z.; investigation, J.Z., P.A.G.-C., C.Z., M.G., F.A., E.Z. and D.C.V.; resources, F.A., H.P., J.E.M. and C.B.; data curation, J.Z., C.Z., F.A. and E.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z., P.A.G.-C., C.Z., M.G., F.A., E.Z. and D.C.V.; writing—review and editing, J.V., H.P., J.E.M., C.B. and D.C.V.; visualization, J.Z., F.A., P.A.G.-C. and J.V.; supervision, P.A.G.-C. and D.C.V.; project administration, F.A., H.P., J.E.M. and C.B.; funding acquisition, F.A., H.P., J.E.M. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the support from the Center for Mining Sustainability, a joint venture between Colorado School of Mines (USA) and Universidad Nacional de San Agustín (Peru).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acosta, J. (2014). Pasado, presente y futuro de la produccion de Oro en el Perú. Horizonte Minero, 97, 66–68, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Adom, R. K., & Simatele, M. D. (2025). Assessing the implications of organised illegal and informal mining activities on the environment in South Africa. Ambio. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldenderfer, M., Craig, N. M., Speakman, R. J., & Popelka-Filcoff, R. (2008). Four-thousand-year-old gold artifacts from the Lake Titicaca. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(13), 5002–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldous, A. R., Tear, T., & Fernandez, L. E. (2024). The global challenge of reducing mercury contamination from artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM): Evaluating solutions using generic theories of change. Ecotoxicology, 33(4–5), 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo Zapata, F. D., Garcia-Chevesich, P. A., Zea Alvarez, J. L., Zevallos Rojas, C. A., & Pizarro, R. (Eds.). (2023). Contaminación y tratamiento de aguas afectadas por la explotación de oro en América Latina. Cátedra Unesco Hidrología de Superficie. Editorial Universitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Barba, A. A. (1640). Huayra, según Álvaro Alonso Barba (1640). Available online: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archivo:Huayra,_según_Álvaro_Alonso_Barba_(1640).jpg (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Bray, W. (1991). La metalurgia en el Perú prehispánico. In A. Bolaños (Ed.), Los Incas y El Antiguo Peru: 3000 Años de Historia (pp. 58–81). Centro de la Villa Cultural. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, W. E. (2023). Enigma of alluvial gold mining in pre-contact Peru—The present is key to the past. Archaeological Discovery, 11, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W. (2012). A history of mining in Latin America: From the colonial era to the present. University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caley, E. R. (1977). Composition of peruvian native gold. The Ohio Journal of Science, 77(2), 141–143. [Google Scholar]

- CEIC. (2025). Gold in a world of edge. Available online: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/blog/gold-world-edge-supply-demand-safe-haven-trends (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Condori, V. (2010). La minería arequipeña a inicios de la república. Entre la crisis de la plata y la fiebre del oro, 1825–1830. Allpanchis, 42, 139–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras Carranza, C. (2010). El Legado Económico de la Independencia en el Perú. Departamento de Economía. [Google Scholar]

- Dammert, A., & Molinelli Aristondo, F. (2007). Panorama de la Minería en el Perú. Osinergmin. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Palacios, J., & Arana Cardó, M. (2016). Historia Ambiental del Perú. Siglos XVIII y XIX (1st ed.). Ministerio del Ambiente. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echave, J. d. (2016). La minería ilegal en Perú. Nueva Sociedad, 263, 131–144. Available online: https://static.nuso.org/media/articles/downloads/7.TC_De_Echave_263.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Espinoza, W. (1995). La civilización inca: Economía, sociedad y estado en el umbral de la conquista hispana. Ediciones Istmo. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson, J. R., Szponar, N., Zambrano, A. A., Bergquist, B., Broadbent, E., Driscoll, C. T., & Bernhardt, E. S. (2022). Amazon forests capture high levels of atmospheric mercury pollution from artisanal gold mining. Nature Communications, 13(1), 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, H., & O’Leary, K. G. (2014). Mercury exposure and health impacts among individuals in the artisanal and small-scale gold mining community: A comprehensive review. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122(7), 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldo Malca, U. F., Sabogal Dunin-Borkowski, A., Facho Bustamante, N., Mori Reaño, M. J., & Giraldo Armas, J. M. (2023). Alluvial gold mining, conflicts, and state intervention in Peru’s southern Amazonia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 13, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, R. J., & Pitcairn, I. (2023). Orogenic gold: Is a genetic association with magmatism realistic? Miner Deposita, 58, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold Fields. (2025). Gold fields conformance to the ICMM mining principles. Available online: https://www.goldfields.com/pdf/sustainbility/sustainability-reporting/international-council-on-mining-and-metals-(icmm)/2022/gold-fields-icmm-performance-expectations-report-2021-2023.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- GRI. (2023). GRI standards 2023—Mining sector standard (GRI 14). Global Sustainability Standards Board. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Research, 32(4), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, V., Vanneste, J., Vuono, D. C., Alejo-Zapata, F. D., Polanco-Cornejo, H. G., Zea, J., Bolaños-Sosa, H. G., Zevallos Rojas, C. A., Figueroa, L. A., & Bellona, C. (2023). Membrane contactors as a cost-effective cyanide recovery technology for sustainable gold mining. Water, 3(7), 1935–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEI. (2025). Available online: https://www.gob.pe/inei/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Lechtman, H. (1976). Metallurgical site survey in the peruvian andes. Journal of Field Archaeology, 3, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechtman, H. (1984). Andean value systems and the development of prehistoric metallurgy. Technology and Culture, 25(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechtman, H., Erlij, A., & Barry, E. J. (1982). New perspectives on Moche metallurgy: Techniques of gilding copper at Loma Negra, Northern Peru. American Antiquity, 47, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccormack, S. (1989). Gods, demons, and idols in the andes. Journal of the History of Ideas, 67, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macquarrie, K. (2008). The last days of the incas. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Manrique, H., & Sanborn, C. A. (2021). La minería en el Perú: Balance y perspectivas de cinco décadas de investigación (1st ed.). Documento de investigación; N.º 16. Universidad del Pacífico. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrugo Negrete, J., Jonathan, M. P., Ramanathan, A. L., Chidambaram, S., Nagarajan, R., & Kumar, P. (Eds.). (2025). Mining impacts and their environmental problems (2024th ed.). Springer. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Mining-Impacts-their-Environmental-Problems/dp/3031721268 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Martinez, G., McCord, S. A., Driscoll, C. T., Todorova, S., Wu, S., Araújo, J. F., Vega, C. M., & Fernandez, L. E. (2018). Mercury contamination in riverine sediments and fish associated with artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Madre de Dios, Peru. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, V., & Werner, T. T. (2024). Impacts for half of the world’s mining areas are undocumented. Nature, 625(7993), 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeish, D. F., Williams-Jones, A. E., Vasyukova, O. V., Clark, J. R., & Board, W. S. (2021). Colloidal transport and flocculation are the cause of the hyperenrichment of gold in nature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(20), e2100689118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MESTI. (2019). National action plan for artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Ghana (ASGM-NAP). Government of Ghana. Available online: https://minamataconvention.org/sites/default/files/documents/national_action_plan/Ghana_ASGM_NAP_Final_March_2022.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- MINAM. (2012). Decreto Legislativo No1105. Establece disposiciones para el proceso de formalización de las actividades de pequeña minería y minería artesanal. Available online: https://www.minam.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Decreto-Legislativo-N°-1105.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- MINAM. (2020). Reglamento del SEIA y lineamientos para la gestión ambiental en minería. Ministerio del Ambiente. Available online: https://www.senace.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/filebase/senacenormativa/NAS-4-6-01-DS-040-2014-EM.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- MINEM. (2024). Incremento de producción en varios metales clave se registró durante el 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minem/noticias/1109430-minem-incremento-de-produccion-en-varios-metales-clave-se-registro-durante-el-2024 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- MINEM. (2025). Available online: https://www.gob.pe/minem (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Mutemeri, N., & Petersen, F. W. (2020). Cooperatives as a model for artisanal and small-scale mining in South Africa. Resources Policy, 68, 101783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nriagu, J. (1993). Legacy of mercury pollution. Nature, 363, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J. A. (2022). The tragic fall of gold production in Peru. Available online: https://www.bnamericas.com/es/entrevistas/la-tragica-caida-de-la-produccion-de-oro-en-peru (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- PERUMIN. (2023). Minería no formal produce el 39.3% de oro del Perú. Available online: https://perumin.com/perumin36/public/es/noticia/mineria-no-formal-produce-el-393-de-oro-del-peru (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Qiu, X., Liu, M., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Q., Lin, H., Cai, X., Li, J., Dai, R., Zheng, S., Wang, J., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Declines in anthropogenic mercury emissions in the Global North and China offset by the Global South. Nature Communications, 16(1), 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regal, A. (1946). Las minas Incaicas. El Diluvio, 1, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes Konings, L. S. (2010). La Conferencia de Bretton Woods. Estados Unidos y el dólar como Centro de la Economía Mundial. Procesos Históricos, 18, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, N. A. (2011). Mercury, mining, and empire: The human and ecological cost of colonial silver mining in the Andes. Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, N. A., & Hagan, N. A. (2012). Mercury production and use in colonial Andean silver production: Emissions and health implications. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosevelt, A. C. (2013). The Amazon and the Anthropocene: 13,000 years of human influence in a tropical rainforest. Anthropocene, 4, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade Hazin, M. (2022). Desarrollo y conflictos socioambientales—Los casos de Colombia, México y el Perú. Macroeconomía del Desarrollo, 137, 45–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samamé, M. (1983a). Historia de la minería peruana—Parte 1. Minería, 177, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Samamé, M. (1983b). Historia de la minería peruana—Parte 3. Minería, 179, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. E. (2002). The Aztecs. The national museum of anthropology. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. M. (2019). Our gold is dirty, but we want to improve: Challenges to addressing mercury use in artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Peru. Journal of Cleaner Production, 222, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMV. (2015). Resolución de Superintendencia N.º 033-2015-SMV/01: Reporte de Sostenibilidad Corporativa. SMV. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/smv/normas-legales/3947586-033-2015 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- SMV. (2020). Resolución de Superintendencia N.º 018-2020-SMV/02: Reporte de sostenibilidad. SMV. Available online: https://governanceconsultants.com/wp-content/uploads/smv-reporte-de-sostenibilidad-corporativa-resolucion-n-018-2020-1.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Swenson, J. J., Carter, C. E., Domec, J. C., & Delgado, C. I. (2011). Gold mining in the Peruvian amazon: Global prices, deforestation, and mercury imports. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e18875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamayo, J., Salvador, J., Vasquez, A., & Zurita, V. (2017). La industria de la mineria en el Peru: 20 años de contribucion al crecimiento y desarrollo economico del pais. Organismo Supervisor de la Inversión en Energía y Minería. [Google Scholar]

- Thorp, R., & Bertram, G. (1985). Peru 1890–1977; Crecimiento y políticas en una economia abierta. Mosca Azul Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, F. G., & De la Torre, G. E. (2022). Mercury pollution in Peru: Geographic distribution, health hazards, and sustainable removal technologies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 29(36), 54045–54059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trench, A., Baur, D., Ulrich, S., & Sykes, J. P. (2024). Gold production and the global energy transition—A perspective. Sustainability, 16(14), 5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumialán, P. H. (2003). Compendio de yacimientos minerales del Perú. Ingemmet. Available online: https://repositorio.ingemmet.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12544/202 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- USGS. (2024). Mineral commodity summaries 2024. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2024/mcs2024.pdf?file=mcs2024.pdf&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- USGS. (2025). Mineral commodity summaries 2025. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025_ver.1.0.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Vera, O., Chávez Riva Gálvez, J., & Sánches Sánchez, W. (2022). Anuario minero 2022. Ministerio de Energía y Minas (MINEM). Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minem/informes-publicaciones/4326371-anuario-minero-2022 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Verbrugge, B., & Besamanos, B. (2016). Formalizing artisanal and small-scale mining: Whither the workforce? Resources Policy, 47, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuono, D. C., Vanneste, J., Figueroa, L. A., Hammer, V., Aguilar-Huaylla, F. N., Malone, A., Smith, N. M., Garcia-Chevesich, P. A., Bolaños-Sosa, H. G., Alejo-Zapata, F. D., Polanco-Cornejo, H. G., & Bellona, C. (2021). Photocatalytic advanced oxidation processes for neutralizing free cyanide in gold processing effluents in arequipa, southern Peru. Sustainability, 13, 9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).