1. Introduction

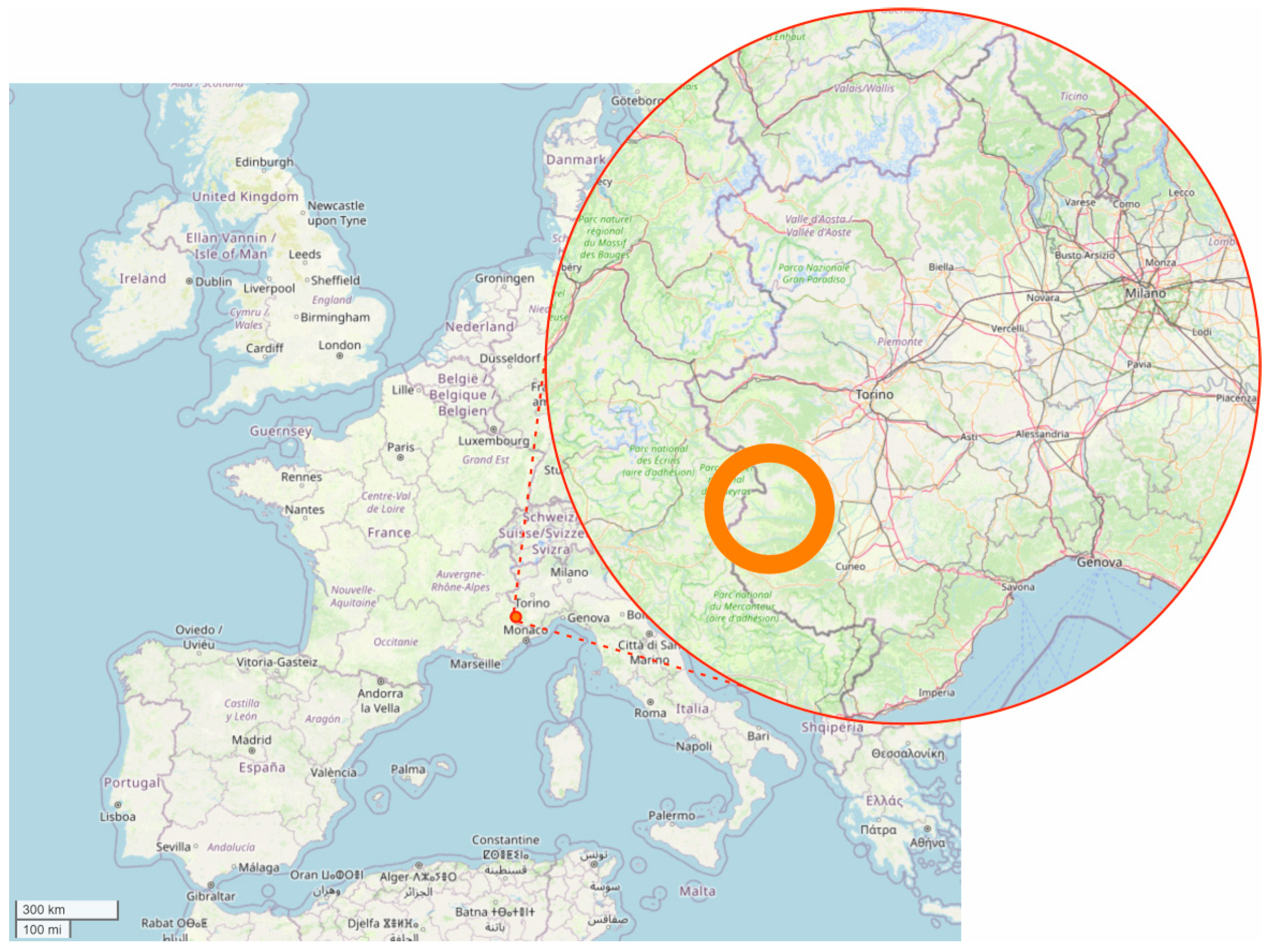

Giovanni has recently turned thirty. His grandparents were from San Lazzaro (see

Figure 1), an Alpine village of a few hundred inhabitants, about 2 h drive from Turin, but his father had left the village in the 1970s, moving to the city to work in one of the many Fiat-related factories. Giovanni was born in the capital city of Piedmont. Thus, San Lazzaro was not his birthplace. However, he spent most of the summers of his youth in the village with his grandparents living there. He had grown up this way, spending nine months in Turin and three in San Lazzaro, somehow reinterpreting one of the key sayings of mountain life: “eight months of winter and four of hell” [

1]. A few years before the pandemic, after completing his studies, he decided to come and live in San Lazzaro because “this town and this valley have become a part of me”. Now, during the summer, he works as a tourist guide in Vallunga, taking visitors to explore the villages of the valley, including “his” San Lazzaro.

I joined the tourist tour almost by chance in the spring of 2022 when I arrived in town in the morning for fieldwork. While waiting for the first interview, I joined the group departing from the square and followed them on the tour that led the half a dozen tourists, mostly foreigners, to visit the key places of the village and to observe and interpret the mountain landscape. “To understand our valleys, you must understand that in the Alps, there are two types of valleys”, explains Giovanni, pointing to the mountain slopes covered in woods and the village composed of houses mostly dating back to the 19th century. “Those that have been touched and transformed by winter tourism, and those that haven’t. Vallunga is one of these…”. Vallunga, in fact, is one of the dozens of valleys in the Western Alps that were not affected by ski investments between the late 19th and 20th centuries [

2]. For example, it did not experience the hillside excavations made to accommodate ski slopes, cableways, and ski lifts; nor the opening of large hotels or timeshare condominiums built to host hundreds of visitors from Italy and abroad for their “ski weeks”; and did not undergo the commercial and urban transformation that these investments brought to villages such as Alagna, Bardonecchia, or Limone Piemonte [

3]. Vallunga, therefore, was excluded from this process of modernization and economic integration, remaining underdeveloped in the post-World War II period. The valley remained largely rural, with almost no industrial settlements, health services, or schools. Thus, it is not surprising to find, even in 2001, the name of San Lazzaro and many other municipalities in the valley among the “depressed areas” under Law 488/1992 (Ministry of Productive Activities Decree, 7 August 2001), and currently it is considered eligible as an inner area municipality [

4]; thus, it is one of the municipalities that can benefit from extraordinary national funds for infrastructure and economic development due to its deprived economic conditions.

To this day, the valley has maintained a very limited level of urbanization. It presents itself as a green territory covered in woods and pastures, where fields are limited to a few hectares cultivated along the river or near the hamlets perched on the steep mountain slopes. This lack of development has, however, in recent history, provided an opportunity for the valley.

Indeed, due to its characteristics, over the past twenty years, the valley has experienced a new economic phase marked by unprecedented outdoor tourism [

5]. Throughout the valley, camping sites and areas for water activities have been built, and new trails have been traced through the woods, connecting various hamlets along panoramic paths. About twelve houses have been renovated to become bed and breakfasts or lodgings for tourists who have discovered a destination for vacations and holidays in Vallelunga. This was a transformation that was not imagined and imaginable for a population that grew up for decades without seeing any other possible future for the valley than slow abandonment. Tourism development also reached San Lazzaro, located halfway down the valley, where five equipped areas and some B&Bs sprung up in the various hamlets of the mountain municipality to accommodate 40 tourists [

6]. In addition, the community has seen its reputation grow due to the success of its food products such as preserves, chestnuts, and, above all, the Formatge di San Lazzaro, the cheese produced by the local five cheese makers.

At the end of the tour, after visiting churches and hamlets, bridges, and streams, Giovanni took us back to the square in San Lazzaro in front of Tina’s, the last grocery store and bar in the town center, a gathering point for the inhabitants of the village and a stopping point for visitors. The store serves as a retailer of bread, milk, and other fresh and long-life products; it is also one of the main stops for those who want to buy Formatge. “Before returning to your homes, however, don’t miss the opportunity to take a piece of San Lazzaro with you. If you want, you can buy our Formatge made by our producers in the store, and if you want to visit them, I can give you their address…”. The message resonates with the expectations of some of the visitors who already asked some questions related to local gastronomy during the tour, confirming a trend in global tourism, namely the growing attention to food [

7,

8]. For tourists, food is a sensory interface through which they get to know and access the visited community. In Giovanni’s words, food, moreover, mobilizes not only emotions and expectations in tourists but also in the producers and the other members of the local community by expressing and responding to their ways of understanding and knowing the local dimension [

9].

Starting from Alberto Capatti and Massimo Montanari [

10], a growing literature shows that the biunivocal connection between food and a specific territory that underpins the emic identification of a certain food as “local” is the result of a creative, dynamic, and mythopoetic cultural process. It expresses a specific, selective way of understanding and imagining the history of the place [

11], and encompasses political and institutional interplay [

12]. Moving from it, this article goes beyond this established knowledge, questioning and exploring the intersection of emotions and meanings of the affective economy [

13] of such products by looking at the forms of knowledge and connection between food, community, and territory that make food a “local” food. Based on ethnographic research and the analysis of food stories [

14] which various actors in the area link to Formatge di San Lazzaro, this contribution suggests the recognition as a “local” product is the result, on one hand, of the geographic localization of production in the particular place, as food supply chains are commonly understood [

15], and, on the other, of the cultural construction of the place that is made possible by the very presence of the product and its capacity of stirring emic narratives concerning the past and future of the community.

To this end, this article begins by introducing the theoretical background and the activities of the research, thus it presents examples of the emic food stories of the Formatge di San Lazzaro. The ethnographic account unravels the affective economy of this product, providing an answer to questions about the role of a product for a local community and its entrepreneurship.

3. Results

In San Lazzaro, there is only one grocery store that also functions as a bar and a family restaurant. If one wishes to purchase bread, some vegetables and fruits, milk, or coffee, they do not go “to the store”, “to the grocery shop”, or “to the provisions store”. They go to “Tina”. Tina is the name of the owner: the shopkeeper. She is now nearly eighty years old and has been running the business for almost fifty years. She was born and raised in San Lazzaro. “I attended all my schools here, up to the fifth grade, because there were no middle schools, and one had to help at home afterward”. The youngest daughter of a farming family, she began working in the shop that she and her husband opened in the 1960s. After her husband’s passing about twenty years ago, she continued the business on her own, while her children “went to the city”, pursuing studies and eventually settling in Turin. Year after year, she witnessed the closure of other businesses in the village: “There were two bakeries and a butcher; there were two bars and a restaurant… there’s nothing left… one by one, they closed… the last one ten years ago, a bar”. In the meantime, Tina “kept going”, adapting her business to continuously meet her customers’ needs. She thus became a multifunctional enterprise, the last outpost in the face of the commercial desertification that had also affected San Lazzaro [UNCEM]. From 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., the door is open for coffee or a purchase. With a little advance notice, she even provides dinner: “Perhaps I shouldn’t, but what am I going to do alone at home?”. Tina is also where tourists come to seek information about the village or to buy some local products. “And I tell them, take some Formatge”.

The forms of Formatge are displayed on a small refrigerated counter alongside other dairy products and industrial cold cuts. They occupy a central position on the counter. There are several types, more or less aged, with the precision of having at least one from each of the local producers. Tina advises customers based on their tastes and intentions, striving for a sales balance that leaves no one dissatisfied. “Why do I do this? It’s our cheese. It’s ours because generations have been making it: it’s the result of hard work and the love we put into cultivating these mountains and taking care of our animals. I try in some way to ensure its continuity by giving everyone a hand… and in recent years, it’s incredible to see how much interest it arouses among tourists. Every time they come in; I see in their eyes the curiosity to learn something authentic about this place. It fills me with pride and hope. When tourists buy it, they help us all survive and save what little is left of the village and its community. I believe that’s why the cheese of San Lazzaro belongs to San Lazzaro”.

Tina’s words resonate with those of Giovanni, the young tour guide. Interviewed after the visit, he recounts how he started his business only a few years ago, just before the pandemic, and immediately noticed visitors’ interest in trying local food. “As a child, tourists used to ask for handicrafts, made of wood or stone. Today, people want to taste the local food. Some already know about Formatge, others discover it thanks to me, to Tina, or other members of the community with whom they speak. It’s always exciting how our product pleases and makes people fall in love with San Lazzaro. Every time they ask me about the cheese and want to taste it, I feel that they are truly embracing the soul of this place…”. For Giovanni, Formatge is not part of his family history: “With the little milk of their cow, my grandfather made butter, certainly not cheese…”. Nevertheless, today Giovanni “feels [the Formatge] as something of mine and of this community”. Indeed, looking at the present and the future of the Alpine community, he sees this product as having a central role in local development: “What else does San Lazzaro produce? Mushrooms and chestnuts, corn. All the villages make the same products here [in the valley], don’t let them tell you otherwise! Formatge, no, that’s different! Each piece tells the story of this land and our elders… and then… When tourists choose to savor our cheese, they keep a part of our economy going and give us hope for tomorrow”. In this sense, in Giovanni’s words, Formatge is an element of continuity between past and present, capable, in its success, of offering a future perspective that would otherwise be difficult to perceive in “a village that is now a desert”.

This sense of perspective is also evident among the producers. Maria is the one who, along with her husband, runs one of the dairies in San Lazzaro. These activities share the same nature as small family-run artisanal businesses. Maria’s is the largest in terms of production capacity, combining a stable, managed by her husband, capable of meeting the entire milk demand required for dairy processing, which is carried out by Maria. While Maria’s business does not depend on other suppliers, the other dairies partially source their milk from other local breeders. Maria is not originally from San Lazzaro; she moved in over forty years ago after her wedding. She was born in another village in the valley. Coming from a farming family, she had no prior experience in cheese-making: “I learned from my mother-in-law… she taught me because she used to make cheese at home. She was my teacher, and today when I think about it, I can’t help but think that our Formatge is still a bit hers… as it is of the people of San Lazzaro who have been making it for centuries… What makes it unique is this history, just like our milk, which comes from animals that eat the grass fodder from our pastures. Can you feel it?” offering a sample of a cheese wheel. “Can you taste the grass? The cheese is our mountain. Each piece is a part of us, of our efforts, and it’s a part of San Lazzaro’s future because as long as we can produce it, we can keep our village alive”.

Maria’s company, like the other local dairy companies, is a member of the producer association established to protect the production of Formatge. It holds and regulates the use of the trademark “Formatge di San Lazzaro”. All the dairy activities in the municipality have access to the trademark, which can be used to brand only cheeses produced with milk obtained from cows raised with a diet based on hay produced in the municipality and supplemented only with cereals. The choice of these regulations aims to maintain small-scale production, limit the risk of industrialization, and allow for specific organoleptic characteristics in the products, as emphasized by Maria herself.

Given the product’s success (in the past decade, the producers indicate the pieces of cheese sold have doubled), these regulations have led to another economic and environmental effect: the revival of hay production by her farmers in the village. “Roughly, a cow eats 20 kg of forage herb per day, and one hectare of land can produce a maximum of two tons of hay per year…” explains Pietro, a fifty-year-old part-time farmer, as he is also employed as a municipal worker in the local administration. Born and raised in San Lazzaro, due to the product’s success, he has seen his farm change over the course of two decades, expanding hay production to lands historically used for this purpose but abandoned since the 1970s. “I started growing hay in those abandoned fields specifically to contribute to Formatge production […]. When I think that it’s the forage herbs that gives our cheese its flavor, it’s as if the landscape becomes a secret ingredient that makes Formatge what it is. And you know, when I see people enjoying our cheese so much, I understand that my work has significant value. It’s also thanks to me that the cheese is like this… the soul of San Lazzaro”.

Even among the population of San Lazzaro not directly involved in Formatge production, there is a strong sense of the product’s importance. “Look, I might be a bad person”, says Mario, a thirty-year-old San Lazzaro native, laughing, “but I don’t eat cheese. That said, I can’t imagine San Lazzaro without its Formatge. It has always been here. It was in every household. It was the way we used milk when there was a little more of it. Today, it’s an asset for our economy. If we still have something left, it’s also because of it, because of the producers”. The sense of importance and connection to the past is even more pronounced among San Lazzaro emigrants who return to the village periodically. Lazzaro, a sixty-year-old who was born and raised in San Lazzaro but left the village with his family in the 1970s to move to the city where he still resides, is an example of this sentiment: “When I think of Formatge, I smile, and I’m overwhelmed with nostalgia. It’s as if every slice encapsulates the history and soul of that place. Its taste takes me back in time… it’s a memory of my childhood and summers spent with family and friends… it’s a connection to my roots that truly makes me feel at home, and when I’m home [in the city] and have a piece, my mind returns here”.

For the tourists who come to the area, Formatge is a “gateway to this place”, “a way to bring San Lazzaro home”. This connection is reinforced not only through the direct experience of purchase, its localization, and personalization but also becomes stronger when linked to contact with the producers: “I had the pleasure of meeting [producer’s name], and he told me the story of this cheese and his family. Beautiful! Now, Formatge is no longer just cheese in my eyes, but the whole of San Lazzaro”.

4. Discussion

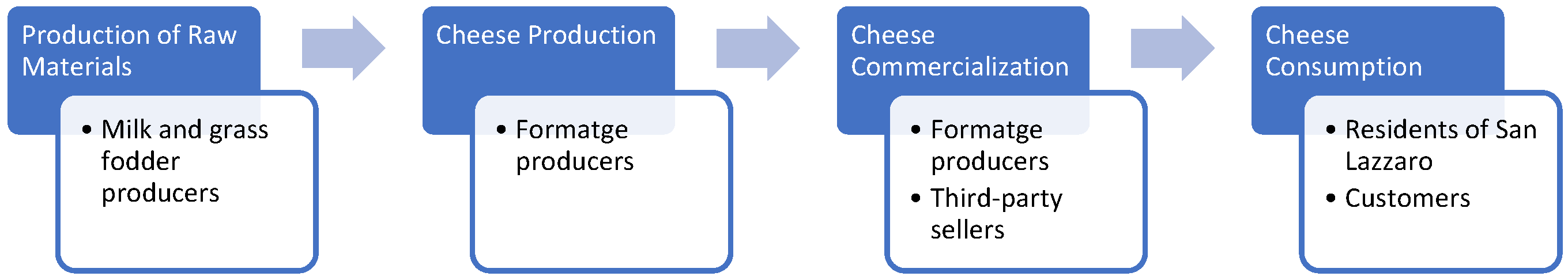

The ethnographic case study offers multiple answers to the question of how a product is embedded into a community, or its role in constructing the same. The first response is of a geographical and economic nature and is exemplified by the concept of a short supply chain. In fact, the production chain of Formatge primarily centers within the municipality of San Lazzaro. The production locations radiate throughout the territory, involving fields, pastures, barns, farms, workshops, and stores. In this sense, the production cycle sees various community members directly involved in the production of raw materials and the transformed product, making it a distributed and collective practice. The stringent regulations of the trademark specification, which limits the possibility of using the name “Formatge di San Lazzaro” to only businesses within the municipality, not only restrict the expansion of the chain beyond the community border but also make it a common heritage for all adhering companies, thus a shared collective asset within the community. Furthermore, in light of its commercial success (measurable in terms of pieces sold, as well as increment of firms’ turnover), this product becomes central to the entrepreneurial projects of local companies, both agricultural and dairy, becoming the object and goal toward which to direct business projects while integrating their fates. Therefore, Formatge offers an initial contribution to the creation of the community by providing at least part of the material basis necessary for its survival.

In addition to this, however, there is a deeper cultural contribution expressed through the affective economy of this product. In formulating the concept of an affective economy, Sarah Ahmed [

13] highlighted how objects effectively catalyze and convey emotions and meanings. Formatge fulfills this function in San Lazzaro by underpinning an imaginary marked by the establishment of multiple interconnections between places, people, and objects. Formatge, in every respect, appears as a narrative framework through which the very idea of the village is given substance. This narrative unfolds along two main axes: the temporal and the spatial, defining not only a regime of historicity, which is “the culturally patterned way of experiencing and understanding history” [

65], specifically the history of one’s own community, but also one of spatiality, indicating the essential elements of the landscape and their interconnections that identify the local and the community.

From the perspective of the regime of historicity, Formatge establishes a linear continuity between past, present, and future. It is substantiated in the perpetuation of cheese production, and thus the use of the landscape for this purpose. On this basis, Formatge becomes both a point of access to and enjoyment of the past and the future. The content of these two categories of temporal storytelling is certainly a cultural product, inherent in the narrative and imagination of the community and individuals living in the present. They are cultural visions of what has been [

66] and what will be [

67]. In this specific case, the past is that of the ancestors’ place, an affective space of origins and knowledge, which is the subject of reverence (as seen in Tina’s words) and nostalgia (as in the case of Lazzaro). The future, on the other hand, is an undefined but vital space, where hope is placed and illuminates the present. It is in the light of the future that the community’s current changes and demographic and commercial erosion, experienced since the mid-20th century, do not assume apocalyptic tones [

68] but rather are transient, contextualized within a local method of hope, namely the collective activation aimed at a specific idea of the future embodied in the object of hope (see [

69]), which centers precisely on Formatge, its production, and commercialization.

From a spatial perspective, the horizon is dictated by the movement of contraction–expansion of human presence in the territory, as well as the relationship with the landscape. These movements can be read diachronically by detailing the cultural image of the past, marked by a decreasing anthropic extension, population, and environmental intensity, a present that projects from a condition of contraction and weakening to a future of new expansion and presence. In the face of this, Formatge not only serves as an element that promotes spatial storytelling but also directs this relationship, giving it meaning through the perspective of sale. In parallel, by being perceived as intimately and indissolubly tied to a place, Formatge defines the community’s identity boundaries, establishing the ideal inside–outside, here–elsewhere [

70], and at the same time becomes an access interface to the local, allowing for an ideal experience even by those who are different from San Lazzaro, as recounted by the tourist, based on and responding to the expectations that guide their visit.

The cultural complexity that develops in the affective economy of Formatge opens a privileged space for observing the entrepreneurial experience of the actors involved and their focus on this product. A classical reading of entrepreneurship would suggest that behind the choice to produce this cheese, there would be solely a rational calculation of opportunities against risks [

71]. On the other hand, even though the local actors do not disregard profit, their history clearly cannot be summarized in a stereotypical model of homo economicus. Their words show how Formatge mobilizes emotions in them, binding them, through cheese, to an experienced past, but above all, placing them within a network of relationships that connect them to people and places, extending to fully cover the dimensions of temporality and spatiality that are characteristic of the affective economy of San Lazzaro. This can be seen in Maria’s words, for example, who, through Formatge, perpetuates an emotional bond with her mother-in-law while also situating herself in a continuity of knowledge with her. It can also be seen in Maria, Giovanni, and Pietro, who, through the taste and idea of the taste of this product, weave a network of relationships that unite pastures and fields with the here and now of the organoleptic experience of cheese. The entrepreneurial experience, the reason why Formatge is produced in San Lazzaro, finds its justification in this network of knowledge and relationships. If, as Matei Candea [

18] states, being within such a network makes a person a member of a local community, the same can be said for how Formatge is part of the community and how the entrepreneurship that underlies its production is deeply embedded in this reality.

5. Conclusions

This article aimed to explore the connection between product and territory that underlies the production of local food, going beyond the geographical nature linked to the structure of a production chain. It found its answer by unraveling the affective economy that revolves around a product, such as Formatge di San Lazzaro. A product is “local” and belongs to a community because it is part of the community, an integral part of a network of affective, cognitive, and spatial relationships that connect it to a territory through time and space. This network is the invisible framework that contextualizes and gives meaning not only to the product but also to the entrepreneurial forms that underlie it.

This response explains the cultural significance of products for territories and why they represent a resource not only economically but also for cultural resilience. It explains their socio-cultural value and uniqueness that goes beyond and transcends the organoleptic characteristics.

This specificity certainly does not shield against phenomena of deterritorialization, and commodification, but it offers an important foundation for local development projects that can be socially and culturally sustainable precisely to the extent that they interpret, narrate, and reinforce this network of meanings.

Unraveling the network of meanings reveals the past and the perceived future of the community. In the context of a country divided by rural marginalization, the history and experience of San Lazzaro tell of a hopeful outlook toward the future. In the face of this propensity, however, elements of fragility and uncertainty that are still alive cannot be ignored. Tourism and gastronomy today offer some answers to this trend, but it is difficult to predict who will take Tina’s or Maria’s place in a few years. Formatge can support new entrepreneurship, but it cannot be assumed that a single product, even if it is a basket, can single-handedly reverse demographic and social trends. Here, there is an urgent call for development policies, and the anthropological community is called upon to lead these initiatives in the spirit of preserving the profound sense of affectionate economies that traverse communities.