Abstract

Community-based approaches in archaeology are poised to make an important contribution to the decolonization of the discipline. Archaeologists who are committed to this agenda are undoubtedly aware that community archaeology is a vibrant and growing research area, but the extent to which the practical aspects and interpretive impact of community archaeology are known beyond its adherents is unclear. This article reviews recent publication trends in highly ranked, international archaeology journals to determine if and what kind of community archaeology is reaching a discipline-spanning audience. The main finding of this analysis is that community archaeology occupies a dynamic but narrow niche within general archaeological scholarship. I argue that this pattern must be confronted and reversed if the transformative potential of community-based research is to be realized in archaeology.

1. Introduction

A decade ago, Sonya Atalay published the now seminal book, Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities [1], a veritable how-to manual for archaeologists seeking to undertake research projects that take seriously the connections between the archaeological record of the past and the people who claim connections to it in the present. Of course, Atalay’s synthesis did not emerge in a vacuum. By the time of that book’s publication in 2012, archaeologists focused on the Black Diaspora had been productively directing community-based research projects for decades [2], while the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990 legally mandated a consultation framework that has, in many cases, evolved into closer (if imperfect) working relationships between archaeologists and American Indian communities in what is now known as the United States [3].

Much of this scholarship advocating for community-based archaeology has characterized this collaborative approach as a “win-win” for both archaeologists and communities. The latter stand not only to learn more about their past, but also to bolster their claims to that past and to particular places. This, in turn, has implications for control of community heritage and, more broadly, sovereignty. Work of this nature is sometimes characterized as archaeology for social justice, explicit calls for which have increased markedly in the 2020s [4,5]. Meanwhile, archeologists fulfill the ethical responsibilities of the profession by engaging with communities [6,7], and furthermore, they frequently arrive at richer and deeper understandings of the archaeological record when they have the insights of community members at their disposal, e.g., [8]. In recent years, archaeologists have gone even further, disarmingly and cogently discussing the profound impact of community-based approaches on their identities as community members, as allies, and as beings with common humanity, perhaps most clearly in the recent volume on “archaeologies of the heart” [9].

Given these multiple perceived upsides of community-based archaeology, one might expect that this agenda would have come to dominate archaeological research in recent years. The question, though, is: has it? In fact, it appears that this critical disciplinary sea change has proven elusive. Instead of permeating—and potentially transforming—the discipline as a whole, community-based research appears to have been relegated to a niche of archaeological practice. For example, with specific reference to the archaeology of post-columbian Indigenous communities, Kurt A. Jordan has noted a “curious divergence between process-oriented writings, which describe how archaeological projects are conducted, and (if you will) works in dirt archaeology, which center on the interpretation of what was discovered in the ground” [10] (p. 73; emphasis in original).

This sort of divergence is profoundly at odds with the potential scope and impact of community-based approaches. Describing a refinement of community-based archaeology that they call “heart-centered archaeology,” Natasha Lyons and Kisha Supernant underscore that it is “not merely a theory or a methodology; it is a practice which expands to the entirety of the archaeological process, from excavation to lab work, from teaching students to sitting with Elders, from working with partners to publishing results. This position fundamentally changes how we consider other humans and non-humans in our practices, as well as how we interpret the past” [11]. Put another way, community-based approaches done right can and should not only involve practice—how we do archaeology (Jordan’s “process-oriented” work); but also impact our interpretations—what we learn through archaeology (Jordan’s “dirt archaeology”).

If archaeologists are actively undertaking community-based research, then these approaches and their impact on archaeological findings and interpretation should be readily apparent in most archaeological scholarship, and the line between process-oriented archaeology and dirt archaeology should not exist. However, if archaeologists are eschewing community archaeology or adopting it in more transactional terms that preclude collaborative interpretation, then Jordan’s characterization of a divide in archaeological scholarship will exist and persist. In this scenario, community archaeology will form a research niche or silo, and its myriad benefits of community-archaeology, ranging from innovative interpretations to advances toward social justice and disciplinary decolonization, will never be fully realized. That just such a niche exists suggested by the founding of multiple journals over the past decade that highlight community-based approaches in archaeology (discussed in more detail below). The question remains: are these approaches percolating across the discipline of archaeology more broadly?

This article seeks to answer this question through a systematic investigation of scholarly journal publication trends in archaeology over the last decade, 2012–2021. Of course, there are other media through which community archaeology is productively presented: scholarly and non-scholarly books, edited volumes, heritage management reports, museum exhibits, digital outlets, talks and roundtables, etc. The present focus on peer-reviewed journals, however, captures the activities and priorities of academic researchers, whose work shapes emergent disciplinary discourse and steers the development of the next generation of archaeologists who may go on to apply community-based approaches if they were trained to do so. Thus, insights gleaned from current journal publication trends may help to contextualize the present and well as the future of community-based archaeology in practice and interpretation. Specifically, this analysis provides preliminary answers to the following questions:

- Have community-based approaches penetrated the discipline of archaeology as a whole, or have they become siloed as an arena of specialized practice?

- To what extent have community-based practices impacted archaeological interpretation?

- Are some kinds of archaeology implementing community-based approaches more than others?

- Are some kinds of communities more engaged with or by archaeological research than others?

For proponents of community-based archaeology, the results of this analysis are, frankly, discouraging. As a discipline, we are failing to capitalize on the diverse gains promised by community-based approaches by perpetuating the divergence between “process-oriented” practice and “dirt”-based interpretation, at least in our patterns of publication in generalized archaeology journals. This is not to say that community-based archaeology is non-existent; following the presentation of the results of the present analysis, I consider the ways in which community archaeology has found a foothold in academic scholarship, and how this foothold may be expanded to normalize archaeology with, by, and for communities.

2. Materials and Methods

I selected eight English-language, peer-reviewed archaeology journals to include in this analysis. All of these journals publish generalized archaeological research from around the world (i.e., they are not country or continent-specific journals, nor do they focus on particular theories or methods), and all reach a potentially global audience; the aims and scope of each journal are listed in Table S1. Their scientific journal rankings vary depending on the index used, but in general, the journals in this sample are highly ranked within the fields of anthropology, archaeology, and/or temporally specific archaeology sub-field (e.g., historical or contemporary archaeology). To identify recent and current publication trends, I focused on volumes published between 2012 and 2021—the decade following the publication of Atalay’s Community-Based Archeology. All but one journal were published over this entire period; Journal of Contemporary Archaeology was first published in 2014.

For each journal, I tallied the number of original research articles published for each year within the focal decade. Because each publisher uses slightly different categorization schemes for their manuscripts, I manually reviewed the contents of each issue in the journal’s online archive; although the precise label varied by journal, I limited my sample to original research articles. Other manuscript types—review articles, forums, debates, editorials, introductions, commentaries, image galleries, corrections, erratum, etc.—were excluded from the sample. The total number of articles for each journal are recorded in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of articles included in sample, sorted by journal.

To identify original research articles that engage community-based approaches, I searched each of the eight journals’ archives using the phrases “community archaeology” and “public archaeology,” recovering articles published between 2012 and 2021 in which those phrases appeared anywhere in the text. My goal was to capture any engagement with community-based approaches, even if it did not rise to the level of a title, abstract, or list of keywords. I excluded results two types of results: (1) articles that only included the phrases “community archaeology” or “public archaeology” in their bibliographies (e.g., part of a title of a reference); and (2) articles that might more appropriately be described as an archaeology of a past community [12], rather than archaeology done with, for, and by a living community.

Having generated this sample, I recorded a number of attributes for each community archaeology article in order to discern patterns and trends within that sample (n = 43). First, I identified type of community collaboration at hand, informed by Atalay [1] (p. 48), who defined the following types of community-based practices along a “collaborative continuum”:

- Consultation, defined as legally mandated communication with a community (e.g., in accordance with NAGPRA)

- Outreach, involving education of self-selected individuals (students, teachers, visitors)

- Multivocal interpretation, in which community members or other “stakeholders” contribute to archaeological interpretations

- Employment by community, where researchers are hired by the community to work on an archaeological project for that community

- Community-based participatory research (CBPR), in which researchers and community members fully and mutually participate in community-driven projects.

I then collected what might be considered “demographic data” for the community-based projects described in each article: the number of co-authors; the geographic region where the project took place; the time period that the project focused on; and the identities of the communities involved in these projects. A few of these attributes require additional clarification.

Regarding a project’s temporal focus, I distinguished between research that tackled historic/post-columbian sites and prehistoric/pre-columbian sites. Specifically, given precocity of community-based approaches in the archaeology of the Black diaspora during the late 20th century (mentioned previously), and preliminary observations of a relatively high proportion of community archaeology articles in journals focused on historical archaeology (Table 1), I wanted to test a hunch that historical archaeologists collaborate with communities more than those specializing in earlier periods. Since historical archaeology research is not exclusively published in historical archaeology journals, however, relying on the journal of publication was an insufficient measure of this attribute.

The identities of communities involved in these projects included three broad categories: descendent, local, and public. For the purposes of this analysis, descendent communities include communities who claim lineal or cultural connections to the archaeological record under consideration; in most cases, these communities were also local to the projects in question. For research that involved descendent communities, I also recorded the identity claimed by those descendants; here, my categories included Indigenous communities (e.g., American Indian, First Nations, Indigenous Australian, etc.), European/European-descent communities, and diasporic communities (e.g., African diaspora, Japanese diaspora). Moving along, local communities do not explicitly claim connections to the archaeological record on the basis of descent. Instead, they occupy the places where archaeological projects are being conducted, and they may embrace a sense of common place-based heritage [13]. Finally, the public includes people who are not tied to the archaeological record under consideration by descent or by close geographic ties, but those who approach it with educational interests; this includes school children, site visitors, and non-archaeologists who encounter archaeological information in digital domains.

I primarily relied on each article’s abstract to glean this information, but I perused each article in more detail as needed to fully flesh out the dataset. Some articles eluded easy categorization (e.g., because they discussed multiple examples), affecting the available sample for the examination of certain attributes; these adjustments are presented where appropriate below. All community archaeology articles included in this analysis are tabulated in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2.

3. Results

3.1. General and Journal-Specific Publication Trends

The primary finding of this analysis is that archaeological research that foregrounds community-based approaches comprises a very small subset of the discipline’s scholarly journal output: just 1% of the 3345 original research articles published in 2012–2021. Although this grim figure is partially attributable to the total absence of community archaeology articles in Antiquity and Journal of Anthropological Archeology, the highest proportion of community archaeology journal articles in a single journal in the sample was 5%; the other ranged from 1–4% (Table 1).

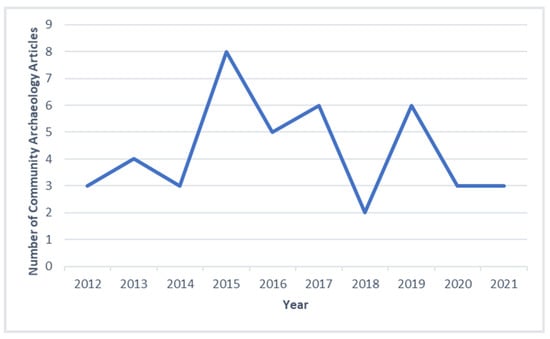

Between 2012 and 2021, the number of community archaeology articles published in these eight journals ranged from two to eight per year (Figure 1), or an average of 4.3 community archaeology articles per year. There is no discernable trend over time toward an increase or decrease in community archaeology articles published during this focal decade. Notably, the year with the most community archaeology publications corresponds with a Special Issue of World Archaeology focused on public archaeology (Volume 46, Issue 2), suggesting that the inflated publication rate for 2015 is not the result of broadening applications of community-based approaches across the discipline.

Figure 1.

Number of community archaeology articles published in sample journals, 2012–2021.

3.2. Types of Collaboration

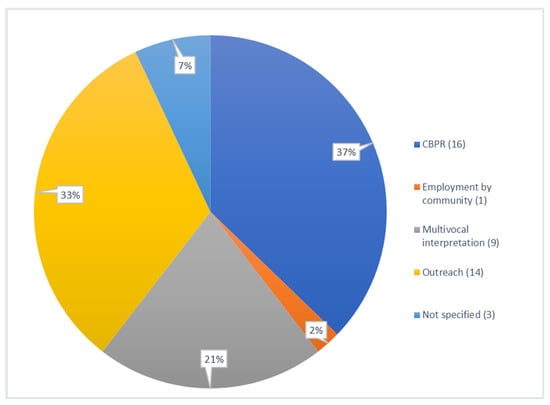

The community archaeology articles included in the sample featured a ranged of community-based approaches (Figure 2), although accounts of employment by a community and legally mandated consultation were rare (n = 1) and non-existent, respectively. The most commonly employed approaches occupy nearly opposite ends of Atalay’s collaborative continuum. On one end, 33% of articles in the sample discussed public outreach and education efforts that tended to engage communities at the back-end of the research project, in settings where researchers share their completed findings with descendent, local, or public communities. On the other end, 37% of articles in the sample described fully community-based participatory research (CBPR) efforts that involved communities from project conception, through execution and revision, to dissemination. The 21% of articles in the sample that foreground multivocal interpretation fall somewhere between outreach and CBPR approaches; although a project may have been initiated or primarily carried out without community participation, the interpretation of findings relied on community knowledge, yielding conclusions that may be quite distinct from what is apparent in the archaeological record alone.

Figure 2.

Types community archaeology represented in articles published in sample journals, 2012–2021.

3.3. Authorship Patterns

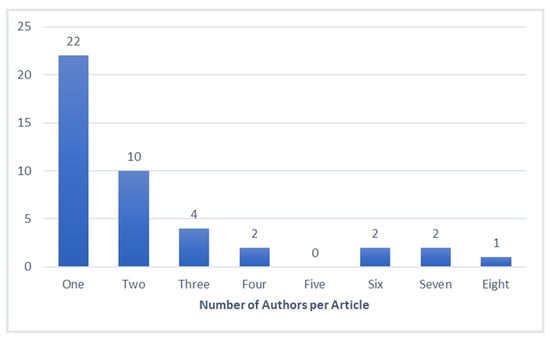

Following Jordan [10], I use authorship as a coarse measure of the application of community-based approaches. In his words, “coauthorship with community partners is the most direct way to decolonize academic writing” (p. 72), but it faces myriad challenges, from the institutional pressures on researchers to publish single-author works to the demands on community members’ time and energy toward projects other than publications. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that half of the community archaeology articles included in the sample are single-author publications by archaeologists (Figure 3). While the rest of the samples is comprised of co-authored articles, many of these appear to be written by multiple academics, rather than a collaborative combination of researchers and community members. In some of these cases, authors explicitly mention the contributions of community knowledge to the interpretation of archaeological findings, yet the bearers of such knowledge are not listed as authors. Certainly, some of these articles were co-authored by community members, but they comprise a distinct minority of the sample. Interestingly, one co-authored article in the sample that did specifically highlight the contributions of community members as co-authors identified the practice as so distinct from standard operating procedure that they label it “counter-archaeology” [14].

Figure 3.

Number community archaeology articles by single authors and multiple co-authors.

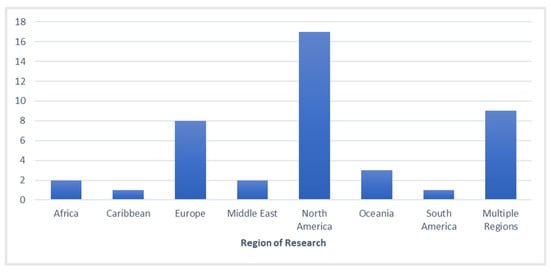

3.4. Geographic Patterns

The 43 community archaeology articles included in the sample included research undertaken in diverse geographic regions (Figure 4). Most articles focused on single projects with single points of origin, but nine addressed research in multiple regions, such that the coverage of some regions is actually higher than the figures below convey. Excluding those articles that tackle multiple regions, studies from North America comprise half of the sample (n = 34); all of these originated what is now known as the United States. Nearly a quarter of the sample addresses European-based research projects, while the remainder cover projects from Africa, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Oceania (including Australia), and South America. No research from East or South Asia was identified in the current sample.

Figure 4.

Location of archaeological projects discussed in community archaeology articles in sample.

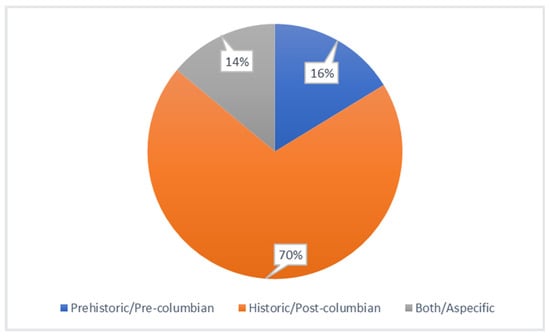

3.5. Temporal Patterns

As expected from the greater proportion of community archaeology articles published in journals dedicated to the more recent past, the majority of community archaeology articles in the sample discussed archaeological projects focused on the historic or post-columbian era (Figure 5). In many cases, these projects included efforts to collect oral histories from community members with memories directly related to the archaeological record under investigation. Although such immediate connections to the past can erode as the age of a site increases, some of the articles in the sample that address prehistoric or pre-columbian sites demonstrate that community knowledge and interests in those settings can also have a profound and productive impact on interpretation, e.g., [15,16].

Figure 5.

Temporal focus of archaeological projects discussed in community archaeology articles in sample.

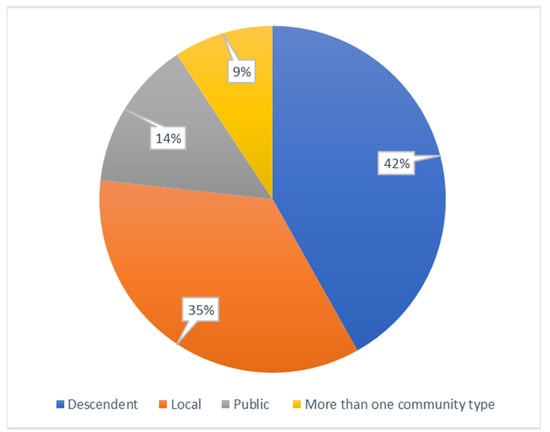

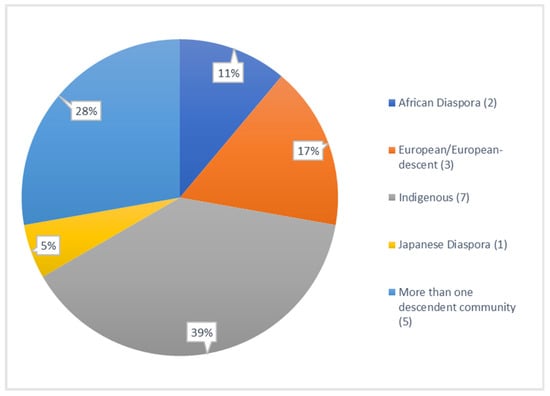

3.6. Community Identities

Articles in this sample reveal that archaeologists are working with a variety of different types of communities (Figure 6). There were 18 articles that discussed community-based projects that engaged descendent communities; of these a majority engaged Indigenous communities in Africa, the Americas, or Oceania (Figure 7). The second most frequently engaged community type was local communities who claim no descendant connection to the archeological record under investigation, while a broader public lacking immediate ties based on descent or location were engaged the least.

Figure 6.

Community types represented in community archaeology articles in sample.

Figure 7.

Descendent community identities represented in community archaeology articles in sample.

4. Discussion

Based on these results, how, then, might we answer the questions posed at the outset of this article? The 43 community archaeology articles culled from the decade-long sample of journal publications demonstrate that archaeologists adopting community-based approach—mostly historical archaeologists, but also some focused on the deeper past—operate at various levels along Atalay’s collaborative continuum. In other words, they are going about community archaeology in a variety of ways, with a variety of different descendent and local communities, in a variety of places. Those projects that involve community contributions at the early and middle-stages of research (e.g., multivocal interpretation, CBPR) frequently cite the contributions of community knowledge to archaeological interpretation, although such contributions are not systematically apparent when it comes to article authorship. These patterns point to the dynamism of community archaeology research from 2012–2021, as well as areas for the growth and development of these approaches, such as in the realms of prehistoric/pre-columbian research and in co-authorship.

However, viewed against the backdrop of all articles published in the selected journals between 2012 and 2021, the broader contributions of community archaeology appear distressingly negligible. Only 1% of articles in these top peer-reviewed archaeology journals involve community-based approaches, so clearly, this agenda has not penetrated the discipline as a whole. Furthermore, the absence of any perceived increase over time in the publication of such research suggests a possible stalling out of the research agenda, at least in the realm of general peer-reviewed journal publications.

Community archaeology does appear elsewhere in the archaeological literature. For one thing, during the same 2012–2021 window, several scholarly edited volumes were published that focused entirely on community-based approaches, e.g., [9,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], as did several single-author books that espouse such a framework, e.g., [24,25]. In addition, numerous peer-reviewed articles were published in scholarly journals concerning archaeological process, such as Advances in Archaeological Practice, and in journals devoted to community-based approaches, including Public Archaeology and Journal Community Archaeology and Heritage. The first and last of these journals were first published in 2014; the appearance of new community archaeology publication outlets in the last ten years is a strong indicator that this is a vibrant and burgeoning area of research. In fact, a more robust answer to some of the questions posed in this article—such as the temporal and geographic foci of community-based research, the types of communities engaged in such projects, and the types of collaborations enacted—could be gleaned from a similar review of articles published in these journals, and/or in journals focused on particular continents, countries, or regions.

At present, though, we must acknowledge that these sorts of publication developments are a double-edged sword: even as they facilitate the publication of more community archaeology research, they also silo such work into a scholarly niche that targets an audience actively seeking to learn about community-based approaches. Rather than reaching archaeologists across the disciplinary spectrum, these books, chapters, and articles are “preaching to the choir” of sympathetic researchers. As a result, the important findings, innovations, and insights of community-based projects remain under-recognized and underappreciated by the wider archaeological community, and the promise of such approaches to the advancement of the field and the interests of diverse community stakeholders remains limited in scope.

5. Conclusions

Inspired by the candor of the heart-centered archaeology agenda cited above [9,11], I offer a brief personal reflection in lieu of a conclusion that simply restates the results of this study. As an academic researcher who strives to implement community-based participatory research programs, I feel constrained at times by the institutional pressure to publish peer-reviewed journal articles related to these efforts. Frankly, nine times out of ten, I would much rather dedicate time and energy to just doing the work—engaging directly with community members, undertaking the research, and compiling findings in ways that meet the interests and needs of community members in ways that scholarly publications often fail to do. These efforts mean more to my non-academic collaborators than a peer-reviewed article, no matter what tier of journal such work might appear in, or how well cited that article might turn out to be. They are also much more fulfilling for me, both personally and as an educator of future archaeologists.

Unfortunately, institutions, including (if not especially) those that comprise academia, are characterized by inertia [26,27]. In the near term, we will likely be slow to eschew certain engrained tendencies, such as but not limited prioritizing peer-reviewed journal articles as professional credentials. Nevertheless, in their contribution to Archaeologies of the Heart, Lisa Hodgetts and Laura Kelvin offer several productive suggestions to shift community archaeology to the forefront of academic archaeology: pushing funding agencies to support community-based research; advocating for more inclusive tenure and promotion policies; welcoming community members into the halls of the academy as faculty, staff, students, and collaborators; and conveying the viability of these approaches to our students, so that the next generation of researchers is poised to accept their worth [27].

Here, I offer another suggestion that we can heed as authors and editors, leveraging our existing workload expectations toward structural change: we must step off the publication sidelines, and start publishing community archaeology research (preferably with community co-authors) in “mainstream” journals with the widest possible audience in archaeology. This strategy will ensure that community-based approaches cross the proverbial radar of researchers who, on account of their own training and experiences, may not fully recognize the potential of community archaeology. This may, in turn, lead to more widely-acknowledged appreciation for the depth of work involved in community-based research, and perhaps to a deeper consideration and valuing of non-traditional forms of scholarship. In addition, widely circulated articles may result in a few (or more!) converts to community-based approaches among readers who would not otherwise have encountered this type of work. Of course, these efforts present their own challenges. It is possible, for example, that manuscripts espousing community-based approaches may be rejected by reviewers with different priorities and points-of-view, which might understandably discourage authors—particularly early career researchers seeking academic employment and tenure—from submitting to “mainstream” journals. To address this specific challenge, researchers in secure or tenured positions have a responsibility to pave the way for our more vulnerable colleagues, and to create a more inclusive publishing landscape for the students we train to embrace community-based approaches.

By disseminating the results, interpretations, and insights from community-based projects in a form that our institutions value highly, we will elevate the standing of community archaeology as a rigorous research agenda [1] (pp. 82–84), as opposed to a niche methodology. In this regard, we have an opportunity to confront the aforementioned divergence between “process” and “dirt” archaeology, and to synthesize community-based practices with interpretations that can only be fully realized through collaborative and participatory frameworks. Based on the “aims and scope” of the journals included in this study, this is exactly the sort of research that should interest their readers, being not only innovative and rigorous, but also relevant and important. As long as just doing the work of community archaeology intersects with certain structural expectations for researchers, we can and should make those expectations work in ways that will not only serve our specific collaborations, but also advance discipline-spanning efforts to decolonize archaeological process, interpretation, and purpose.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/humans2040018/s1, Table S1. Aims and scope of journals included in this analysis; Table S2: Community archaeology articles published in journal sample, 2012–2021.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publication data for the journals included in this analysis were obtained from each journal’s online repository, as follows:

- World Archaeology: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwar20

- Antiquity: https://antiquity.ac.uk/issues

- Journal of Field Archaeology: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjfa20

- Journal of Anthropological Archaeology: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-anthropological-archaeology/issues

- Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory: https://link.springer.com/journal/10816/volumes-and-issues

- Historical Archaeology: https://link.springer.com/journal/41636/volumes-and-issues

- International Journal of Historical Archaeology: https://link.springer.com/journal/10761/volumes-and-issues

- Journal of Contemporary Archeology: https://journal.equinoxpub.com/JCA/issue/archive

Acknowledgments

Preliminary data collection for this article was accomplished by students in my 2022 Community Archaeology class at Appalachian State University: Evan Batchelor, Leksie Cameron, Kendra Casse, Owen Flock, Sydney Maddox, Christian Peterson, Morgan Robinson, Jacob Sharp, Megan Shaw, Gracie Simms, Molly Switzer, and Isabella Vargas. I would like to thank Cheryl Claassen for the invitation to contribute to this issue, and the communities who have allowed me to work with them over the years and who have shaped my appreciation for community-based approaches in archaeology, in particular the Plott Farm Neighborhood in Canton, North Carolina, USA and the Junaluska Heritage Association in Boone, North Carolina, USA.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Atalay, S. Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Blakey, M. Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race. Curr. Anthropol. 2020, 61 (Suppl. 22), S183–S197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, S.E.; Colwell, C. NAGPRA at 30: The Effects of Repatriation. Annu. Rev. Anthr. 2020, 49, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flewellen, A.O.; Dunnavant, J.P.; Odewale, A.; Jones, A.; Wolde-Michael, T.; Crossland, Z.; Franklin, M. “The Future of Archaeology Is Antiracist”: Archaeology in the Time of Black Lives Matter. Am. Antiq. 2021, 86, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laluk, N.C.; Montgomery, L.M.; Tsosie, R.; McCleave, C.; Miron, R.; Carroll, S.R.; Aguilar, J.; Thompson, A.B.W.; Nelson, P.; Sunseri, J.; et al. Archaeology and Social Justice in Native America. Am. Antiq. 2022, 87, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for American Archaeology: Ethics in Professional Archaeology. Available online: https://www.saa.org/career-practice/ethics-in-professional-archaeology (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- World Archaeological Congress: Code of Ethics. Available online: https://worldarch.org/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Spector, J.D. What This Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village; Minnesota Historical Society Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Supernant, K.; Baxter, J.E.; Lyons, N.; Atalay, S. (Eds.) Archaeologies of the Heart; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.A. Categories in Motion: Emerging Perspectives in the Archaeology of Postcolumbian Indigenous Communities. Hist. Archaeol. 2016, 50, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, N.; Supernant, K. Introduction to an Archaeology of the Heart. In Archaeologies of the Heart; Supernant, K., Baxter, J.E., Lyons, N., Atalay, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, M.; Yaeger, J. (Eds.) The Archeaology of Communities: A New World Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. Private property, public archaeology: Resident communities as stakeholders in American archaeology. World Archaeol. 2015, 47, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.; Fisher, A.; Hutchinson, J.; Jeffrey, S.; Jones, S.; Maxwell, M.; Watson, J.S. Disrupting the heritage of place: Practising counter-archaeologies at Dumby, Scotland. World Archaeol. 2017, 49, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jopela, A.; Fredriksen, P.D. Public archaeology, knowledge meetings and heritage ethics in southern Africa: An approach from Mozambique. World Archaeol. 2015, 47, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, L.M.; Kearney, A. Sitting in the gap: Ethnoarchaeology, rock art and methodological openness. World Archaeol. 2016, 48, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coningham, R.; Lewer, N. (Eds.) Archaeology, Cultural Heriage Protection and Community Engagement in South Asia; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalglish, C. (Ed.) Archaeology, the Public and the Recent Past; Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moshenska, G. (Ed.) Key Concepts in Public Archaeology; University College of London Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, P.R.; Kehoe, A.B. (Eds.) Archaeologies of Listening; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, P.R.; Pikirayi, I. (Eds.) Community Archaeology and Heritage in Africa: Decolonizing Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.; Lea, J. (Eds.) Public Participation in Archaeology; Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, H.; Pudney, C.; Ezzeldin, A. (Eds.) Public Archaeology: Arts of Engagement; Archaeopress Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, N. Where the Wind Blows Us: Practicing Critical Community Archaeology in the Canadian North; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mickel, A. Why Those Who Shovel Are Silent: A History of Local Archeological Knowledge and Labor; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts, L.; Kelvin, L. At the Heart of the Ikaahuk Archaeology Project. In Archaeologies of the Heart; Supernant, K., Baxter, J.E., Lyons, N., Atalay, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surface-Evans, S. “I Could Feel Your Heart”: The Transformative and Collaborative Power of Heartfelt Thinking in Archaeology. In Archaeologies of the Heart; Supernant, K., Baxter, J.E., Lyons, N., Atalay, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).