A Novel Method That Is Based on Differential Evolution Suitable for Large-Scale Optimization Problems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A unified and modular DE framework is introduced, integrating multiple control mechanisms within a single optimization scheme, including mutation weighting, parent selection, local refinement activation and termination criteria.

- A k-means-based population sampling strategy is incorporated to preserve population structure and improve sampling efficiency in high-dimensional search spaces.

- Alternative mechanisms for computing the differential weight parameter are proposed, incorporating number-based, random and migrant strategies to enhance adaptability in large-scale optimization problems.

- An optional tournament-based parent selection strategy is employed to improve selection pressure while maintaining population diversity and robustness.

- A periodic local optimization refinement using deterministic local optimizers, such as BFGS, is integrated to enhance solution accuracy and accelerate convergence without compromising global exploration.

- A population-based termination criterion is introduced to enable early stopping when convergence stagnation is detected, significantly reducing unnecessary objective function evaluations.

- The proposed framework is specifically designed for large-scale global optimization problems and aims to achieve a more effective balance between exploration and exploitation compared to classical DE variants.

2. Differential Evolution Algorithm

2.1. The Original Differential Evolution Method

| Algorithm 1 Original Differential Evolution Algorithm |

INPUT - f: objective function - : population size - : Crossover rate - F: Differential weight - n: Problem dimension OUTPUT - INITIALIZATION -Generate an initial population of candidate solutions , uniformly at random within the search bounds. -Evaluate the objective function for all individuals. -Set as the individual with the best objective value. main pseudocode 01 while stopping criterion is not met do 02 for each individual {1…} do 03 Select randomly three agents {1…} 04 Generate mutant vector 05 Select a random index R {1…n} 06 for each dimension to n do 07 Generate a random number 08 if then 09 Set 10 else 11 Set 12 endif 13 endfor 14 if then 15 Replace 16 endif 17 endfor 18 endwhile 19 return |

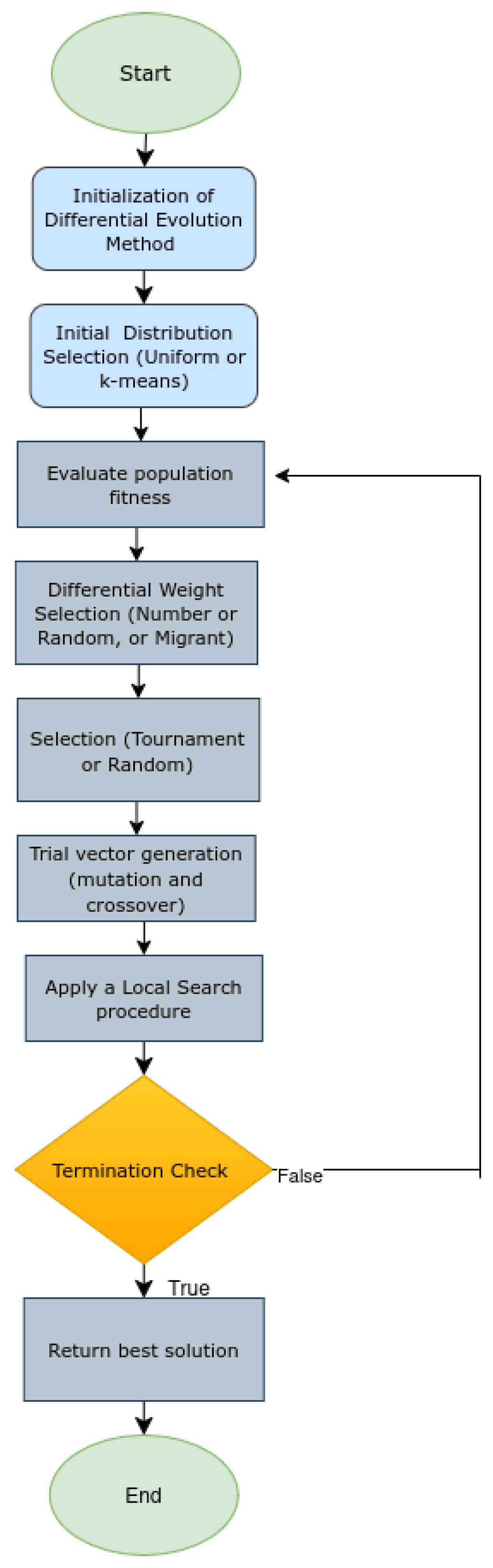

2.2. The Proposed Differential Evolution Method

- Alternative mechanisms for differential weight computation.

- A k-means-based population sampling strategy is incorporated to preserve population structure and improve sampling efficiency in high-dimensional search spaces.

- Optional tournament-based parent selection strategies.

- Periodic local refinement using a deterministic local optimizer.

- A population-based termination criterion.

| Algorithm 2 Proposed Algorithm |

INPUT - f: objective function - : population size - : tournament size - : maximum number of iterations - : termination criteria - : Crossover rate - F: Differential weight - n: Problem dimension - k: iteration counter OUTPUT - INITIALIZATION -Set as the population size (number of agents) -Create randomly NP agents -Compute the fitness value = for each agent -Set as the local search rate -Set as maximum number of iterations -Set as termination criteria -Set as tournament size -Set as the iteration counter -Set the parameter , with -Select the differential weight method F: (a) Number: F is constant value. (b) Random: . (c) Migrant: migrant-based mechanism [39]. main pseudocode 01 while stopping criterion is not met do 02 for each individual {1…} do 03 Select the agent 04 Select randomly three distinct agents 05 Choose a random integer R 06 Create a trial point 07 for {1…n} do 08 Select a random number 09 if then 10 Set 11 else 12 Set 13 endif 14 endfor 15 Set 16 if then 17 Replace 18 endif 19 Select a random number 20 if then 21 Apply local search [38] 22 endif 23 endfor 24 25 if then terminate 26 Compute = 27 if for iterations then terminate. 28 endwhile 29 return |

3. Experiments

3.1. Test Functions

3.2. Experimental Results

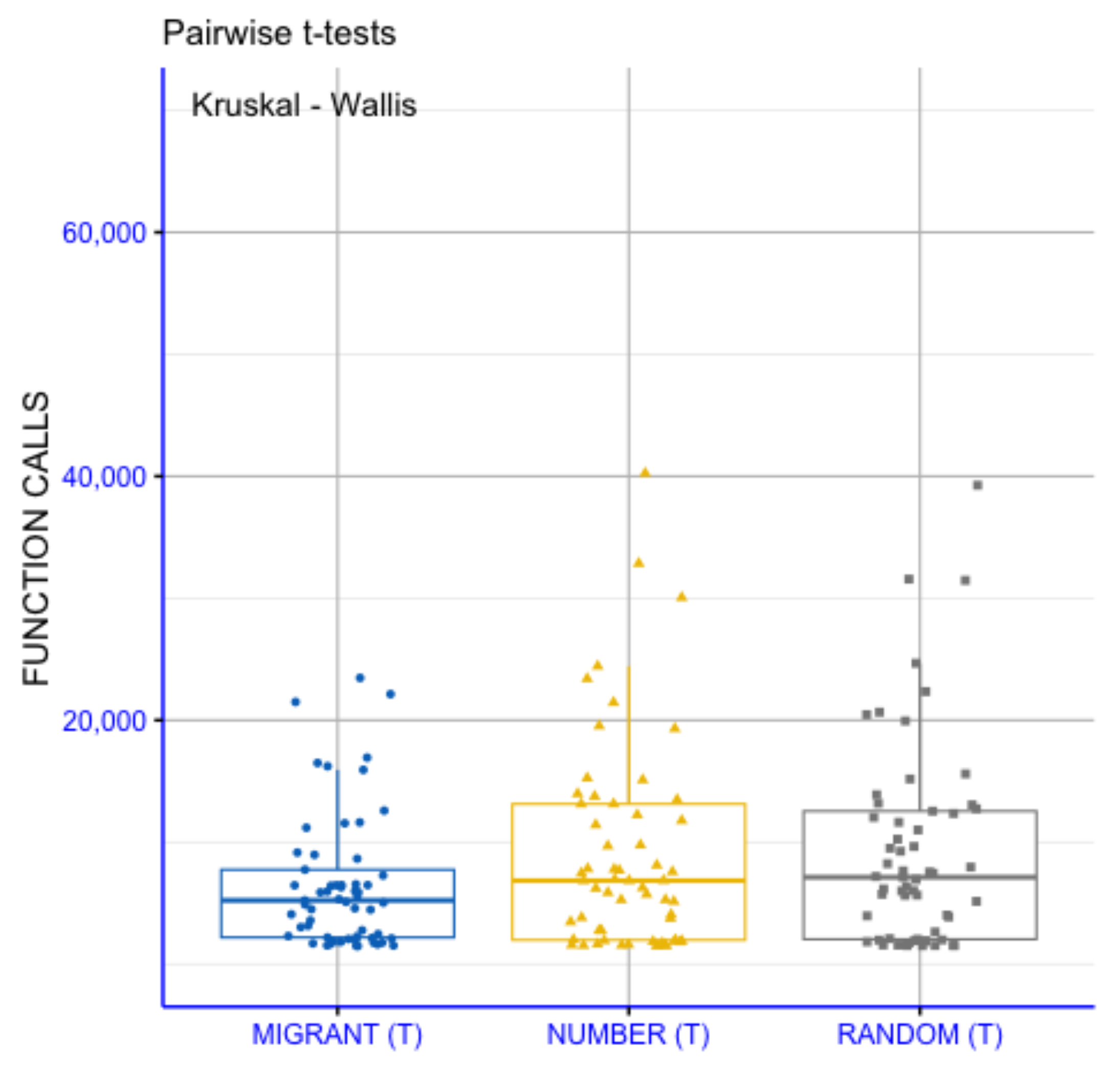

3.3. The Effect of Differential Weight Mechanism

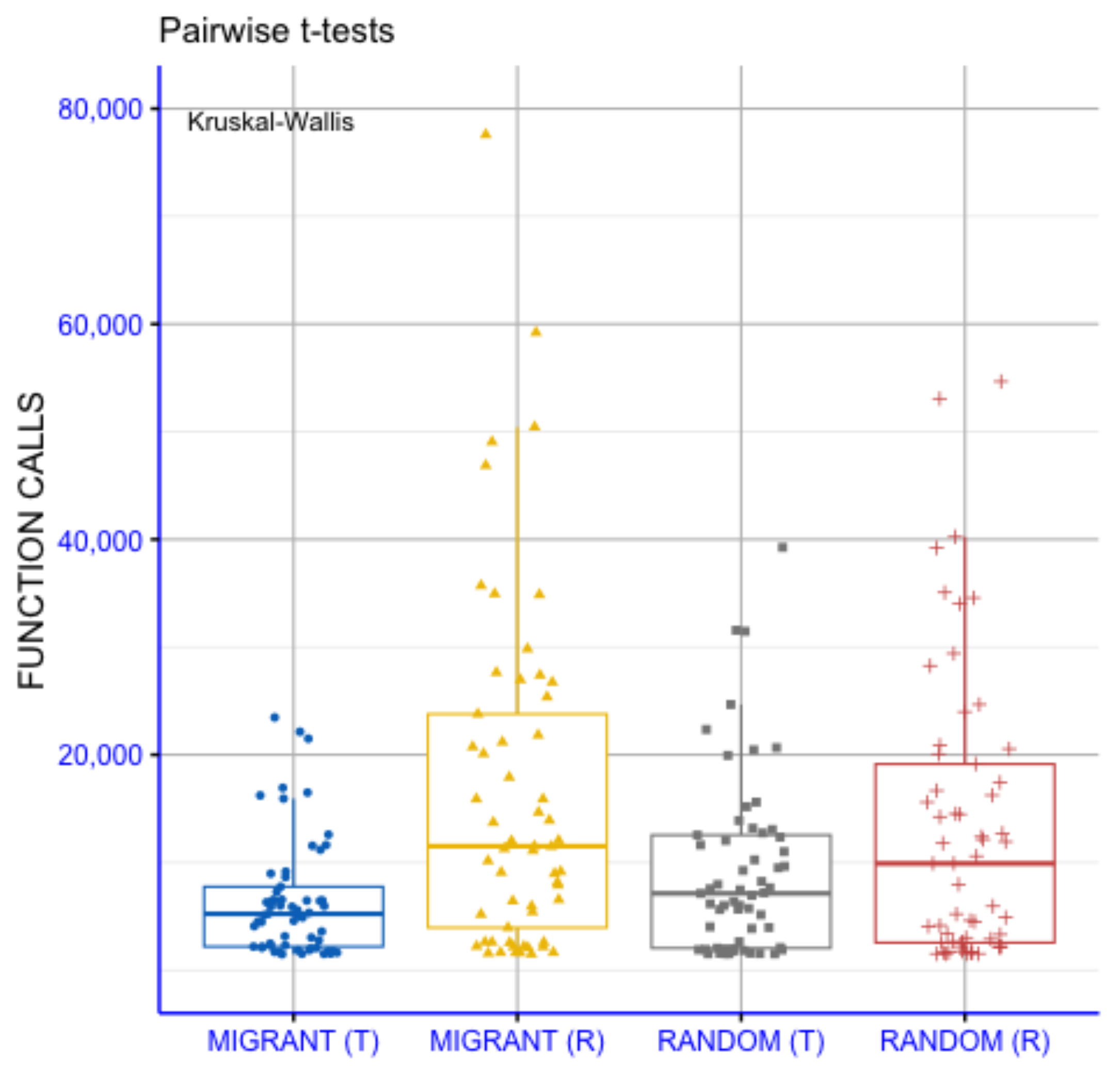

3.4. The Effect of Selection Mechanism

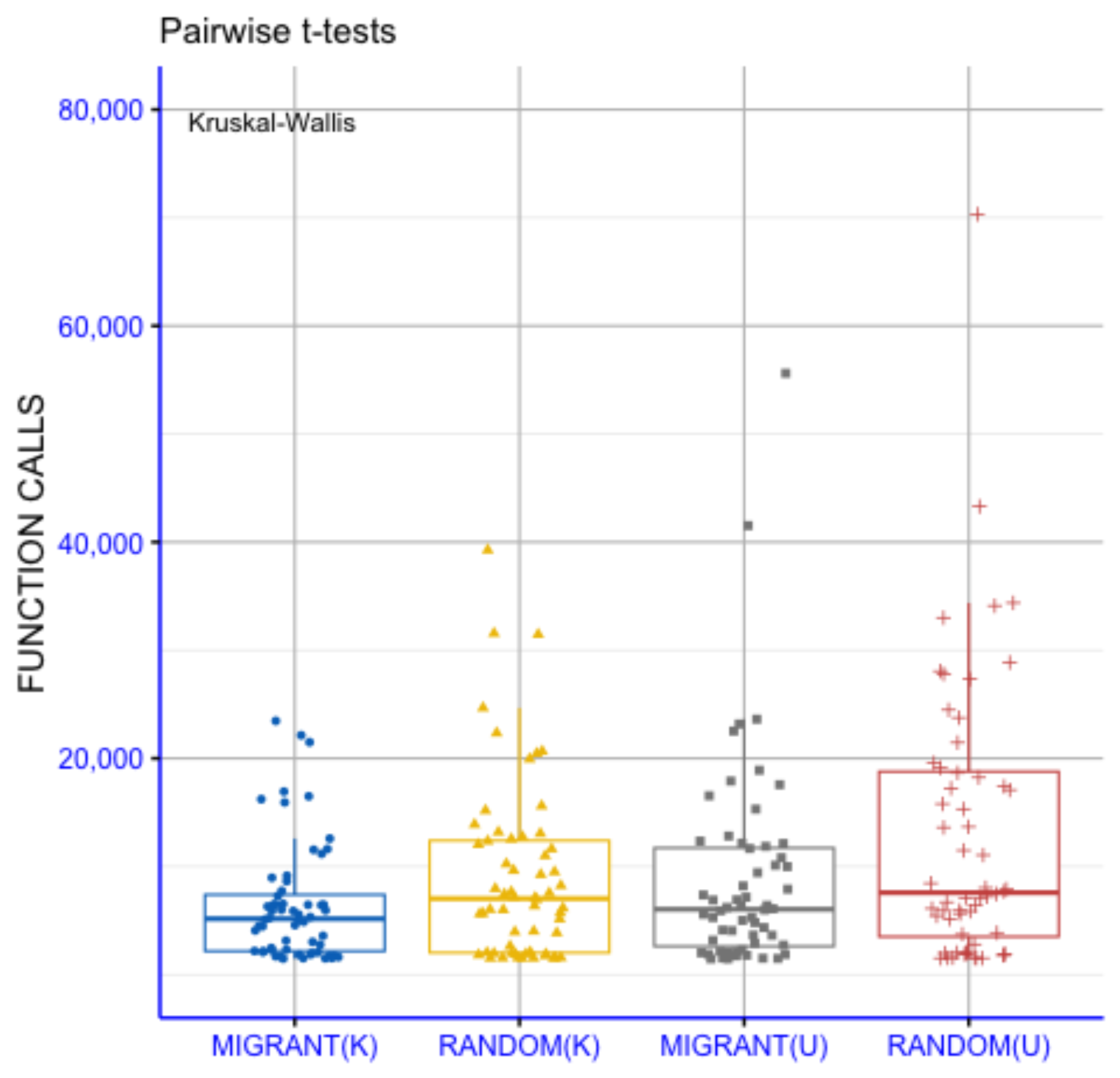

3.5. The Effect of Sampling Method

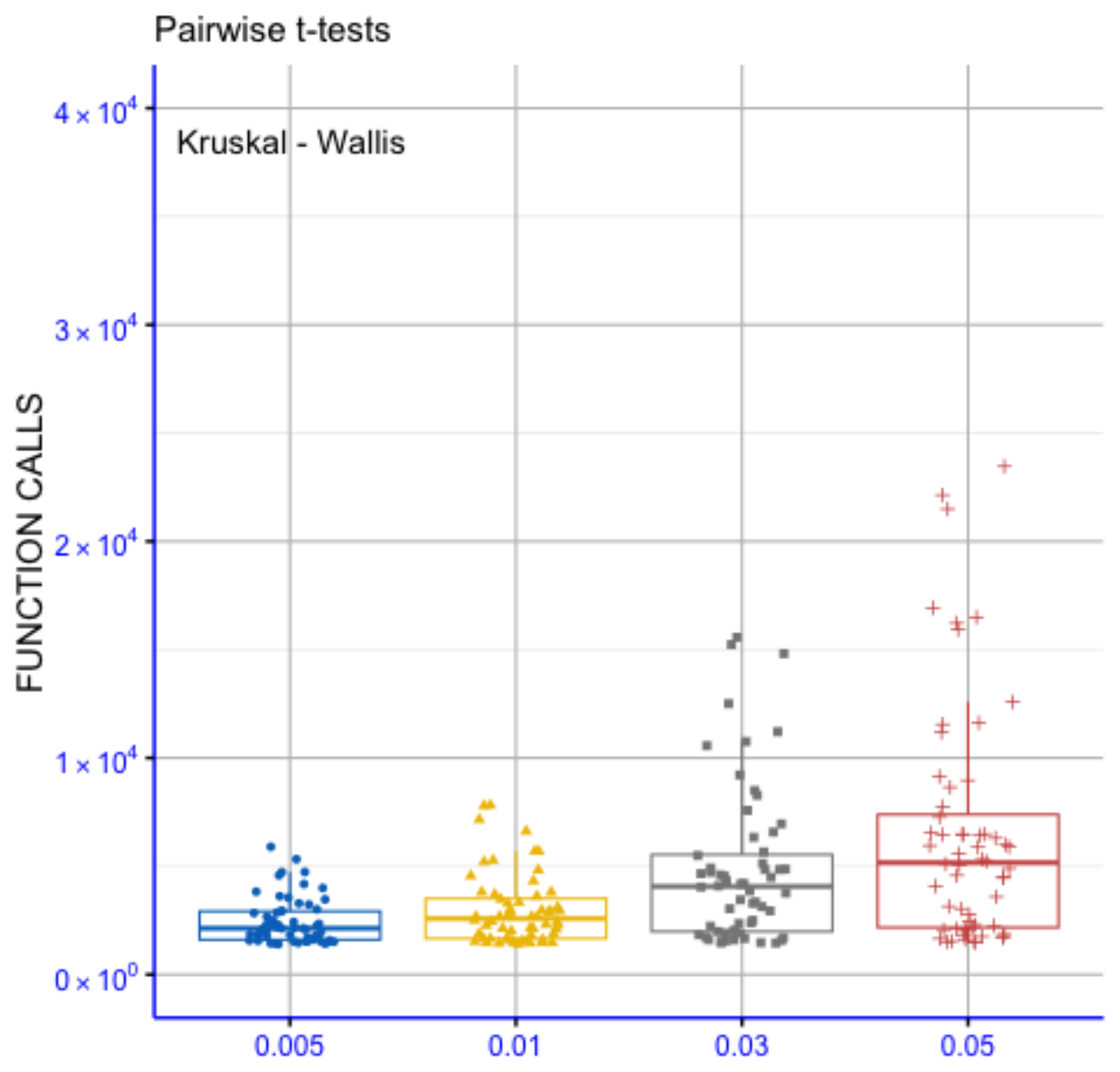

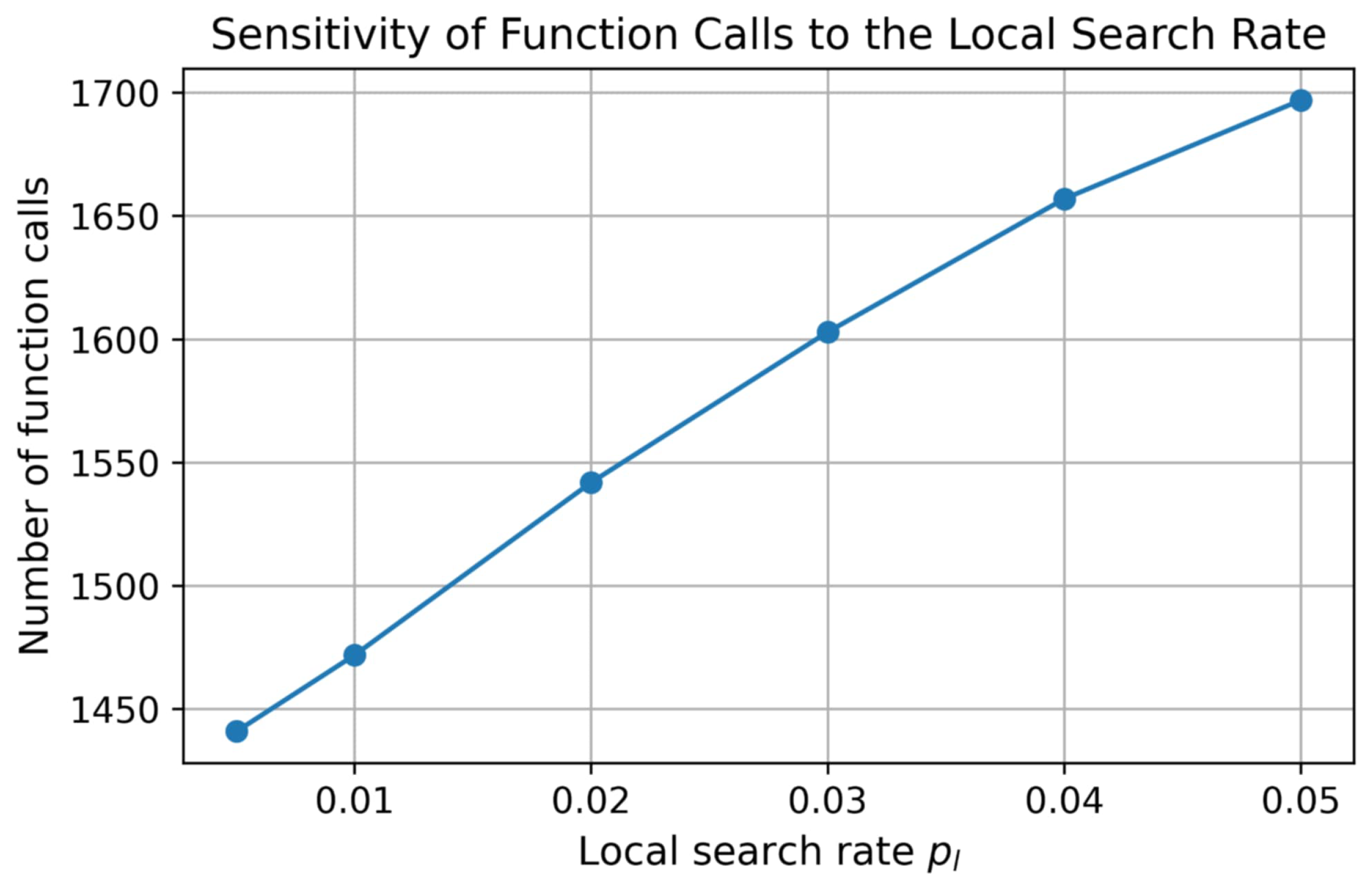

3.6. The Effect of Local Search Rate

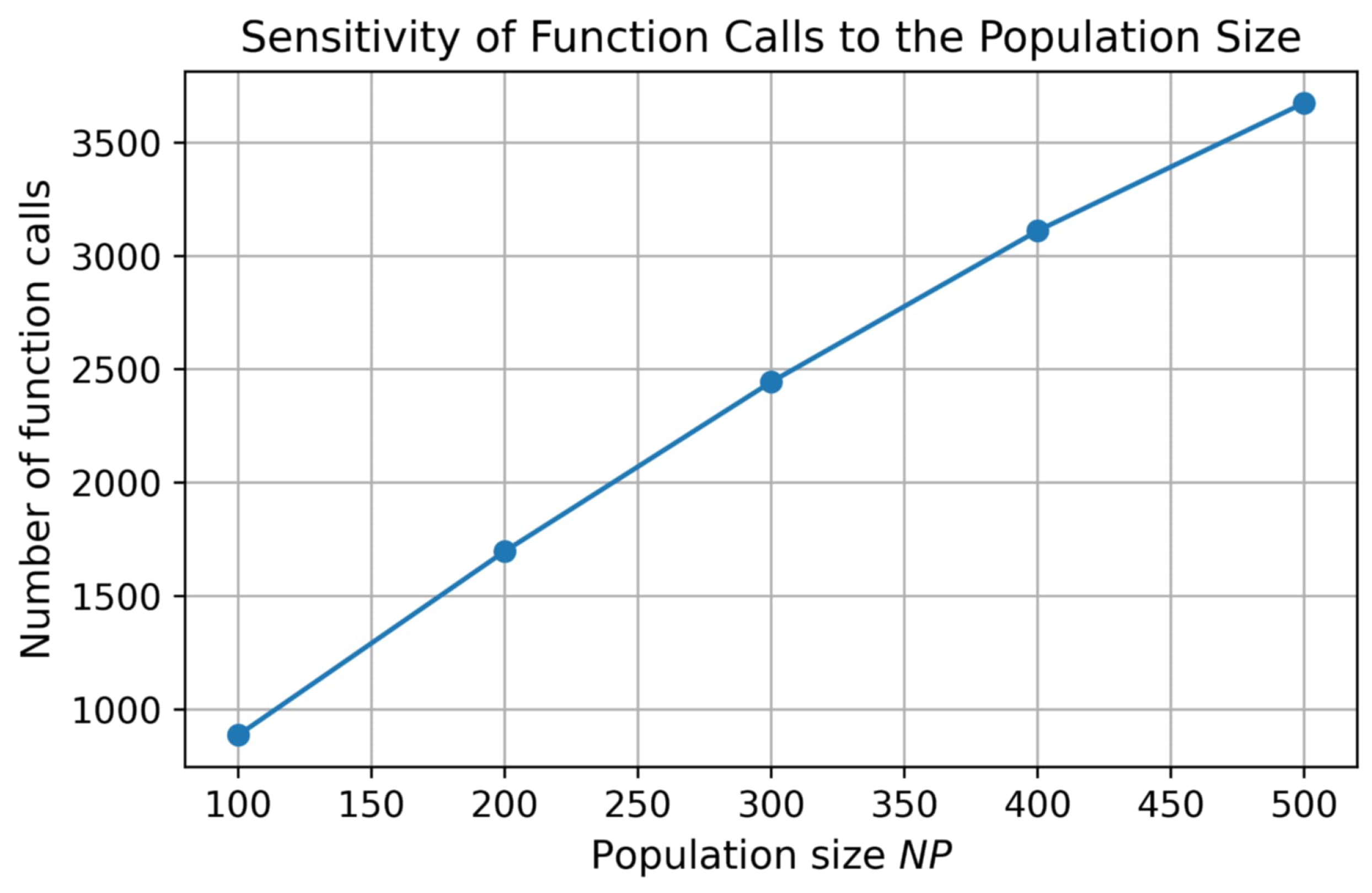

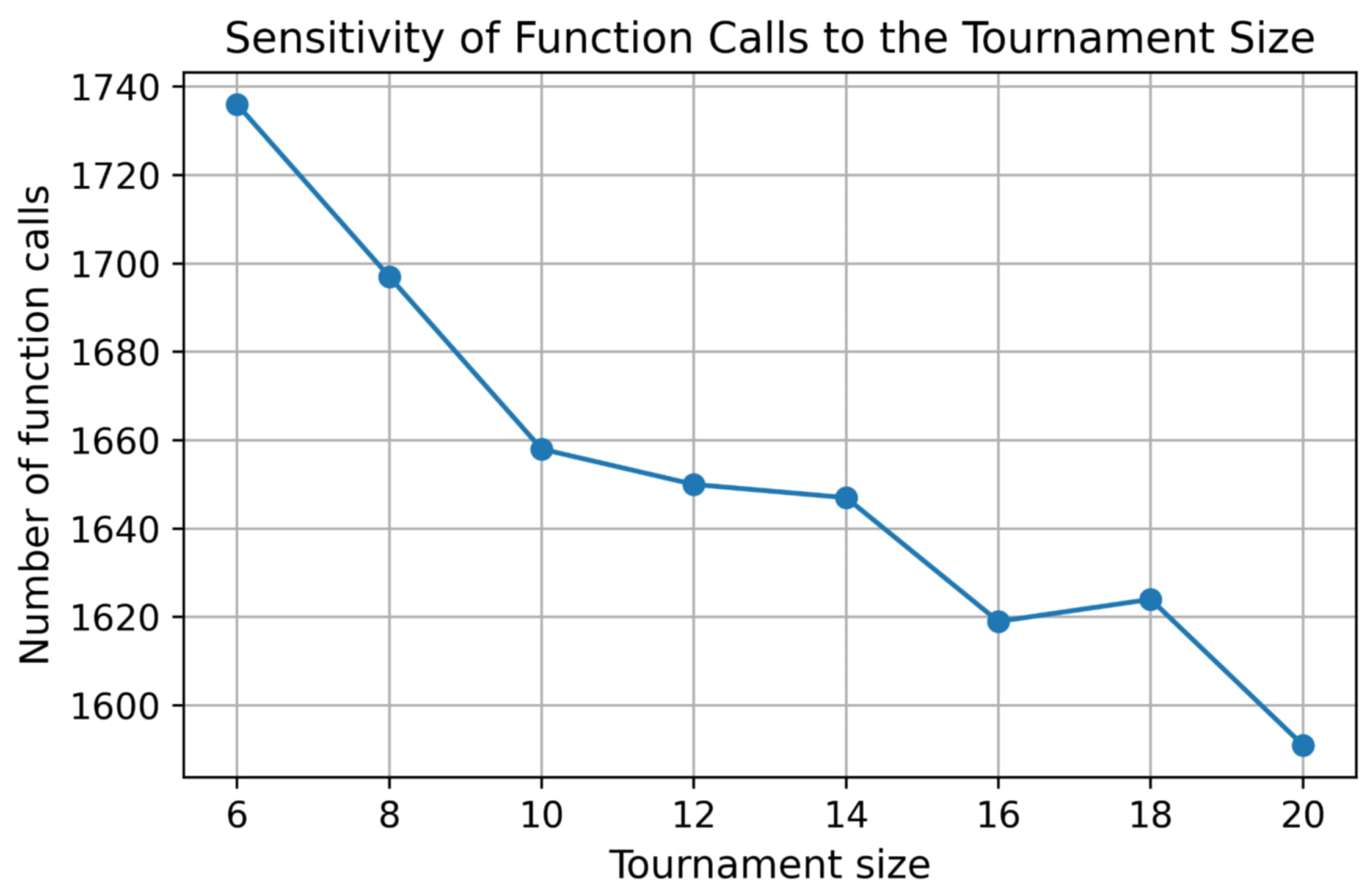

3.7. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

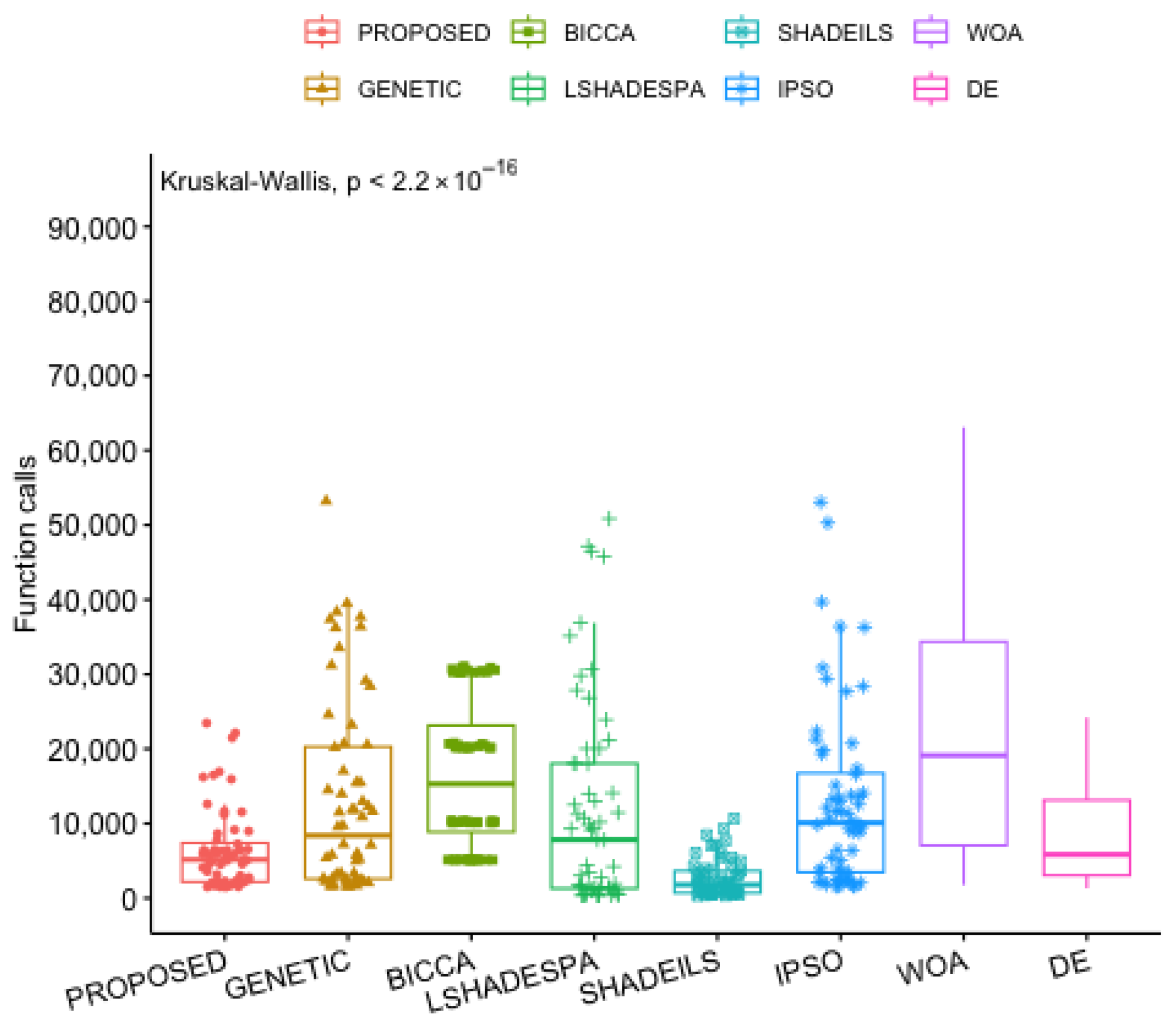

3.8. The Proposed Method in Comparison with Others

3.9. Practical Problems

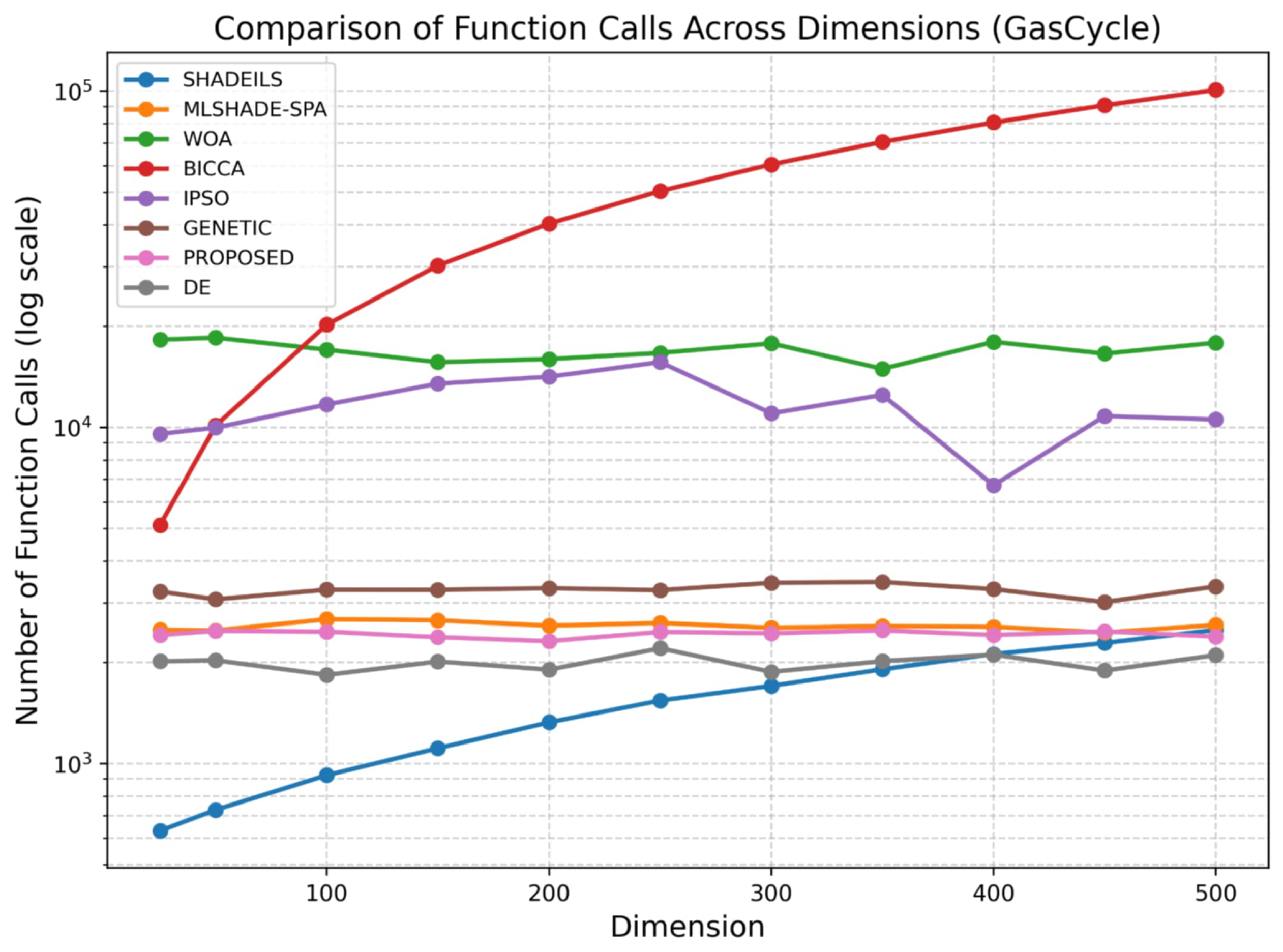

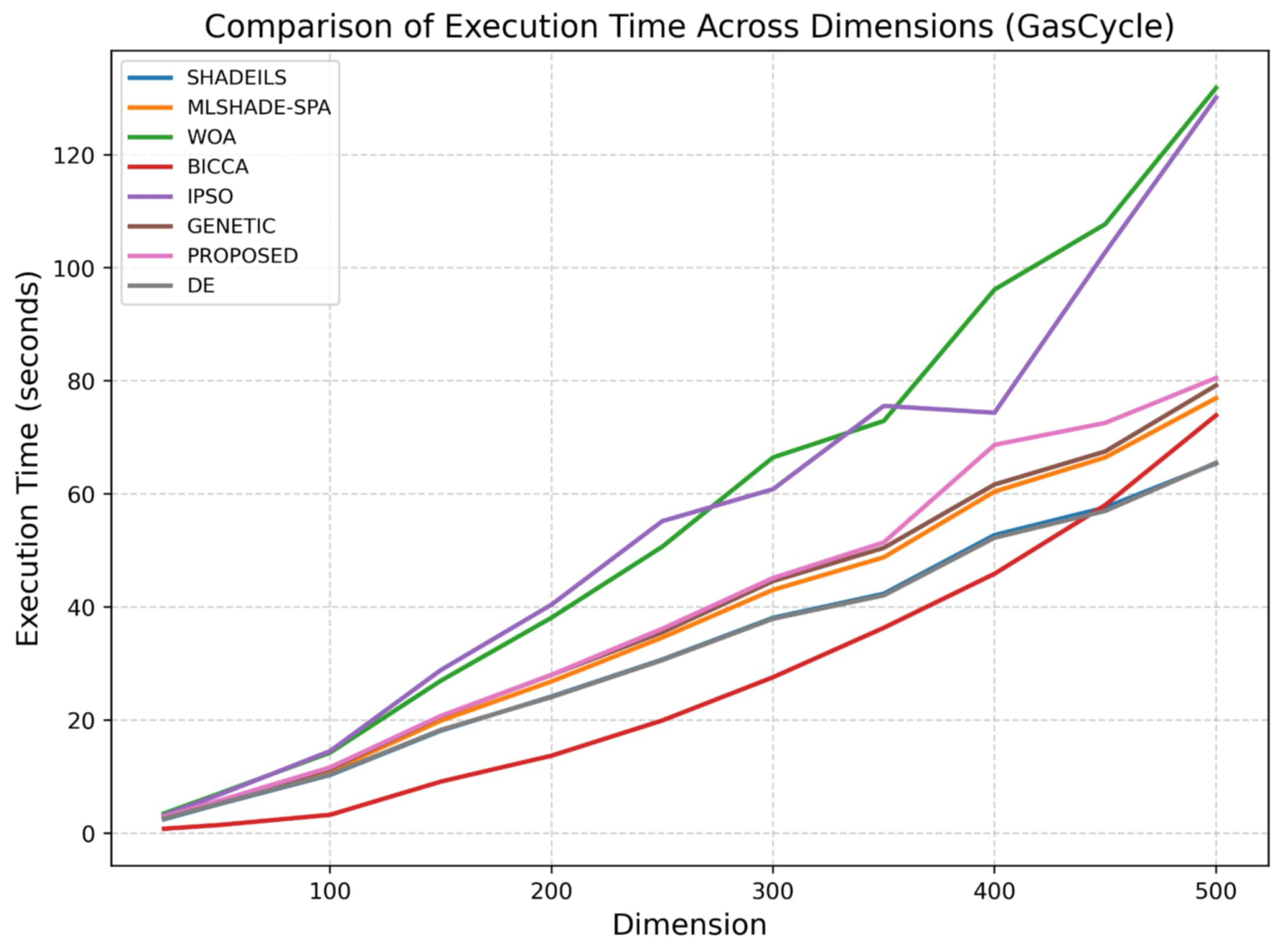

- GasCycle Thermal CycleVars: .Bounds:Penalty: infeasible .The GasCycle scenario presents a more computationally demanding optimization problem, allowing a clearer assessment of algorithmic scalability under increased complexity.For GasCycle, as illustrated in Figure 10, the proposed algorithm maintains a stable and competitive number of function calls across all dimensions. Compared to methods that show pronounced growth in evaluations at higher dimensions, the proposed approach exhibits a more controlled increase, indicating effective adaptation to the structure of the GasCycle problem. This behavior suggests that the method can efficiently utilize function evaluations without excessive computational overhead in large-scale cases.The execution time analysis for GasCycle, shown in Figure 11, aligns closely with the function call results. The proposed algorithm achieves a balanced runtime profile, with execution time increasing smoothly as dimensionality grows. In contrast to approaches that suffer from substantial runtime escalation, the proposed method maintains reasonable computational demands even at high dimensions, highlighting its suitability for complex, large-scale optimization tasks.

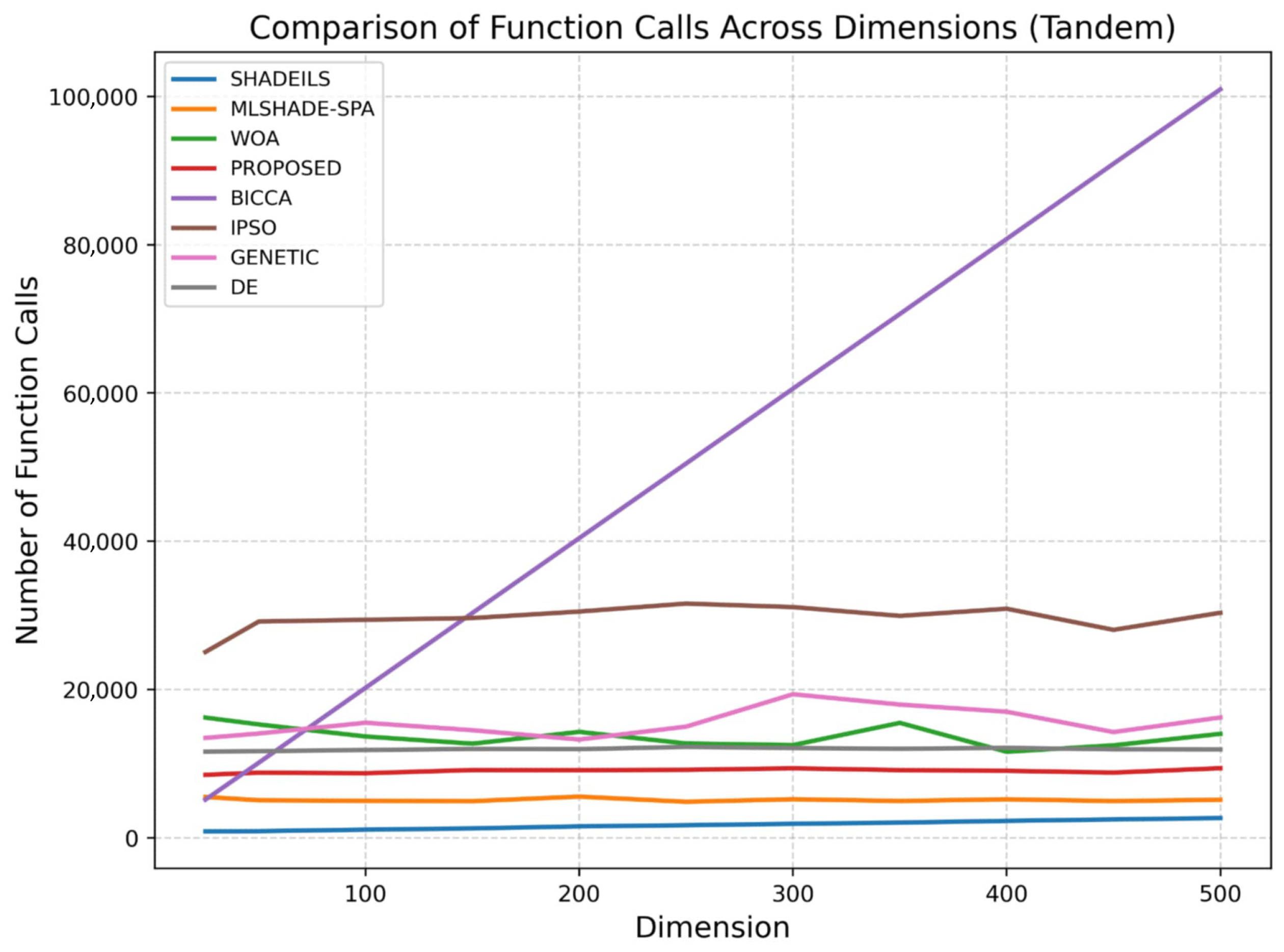

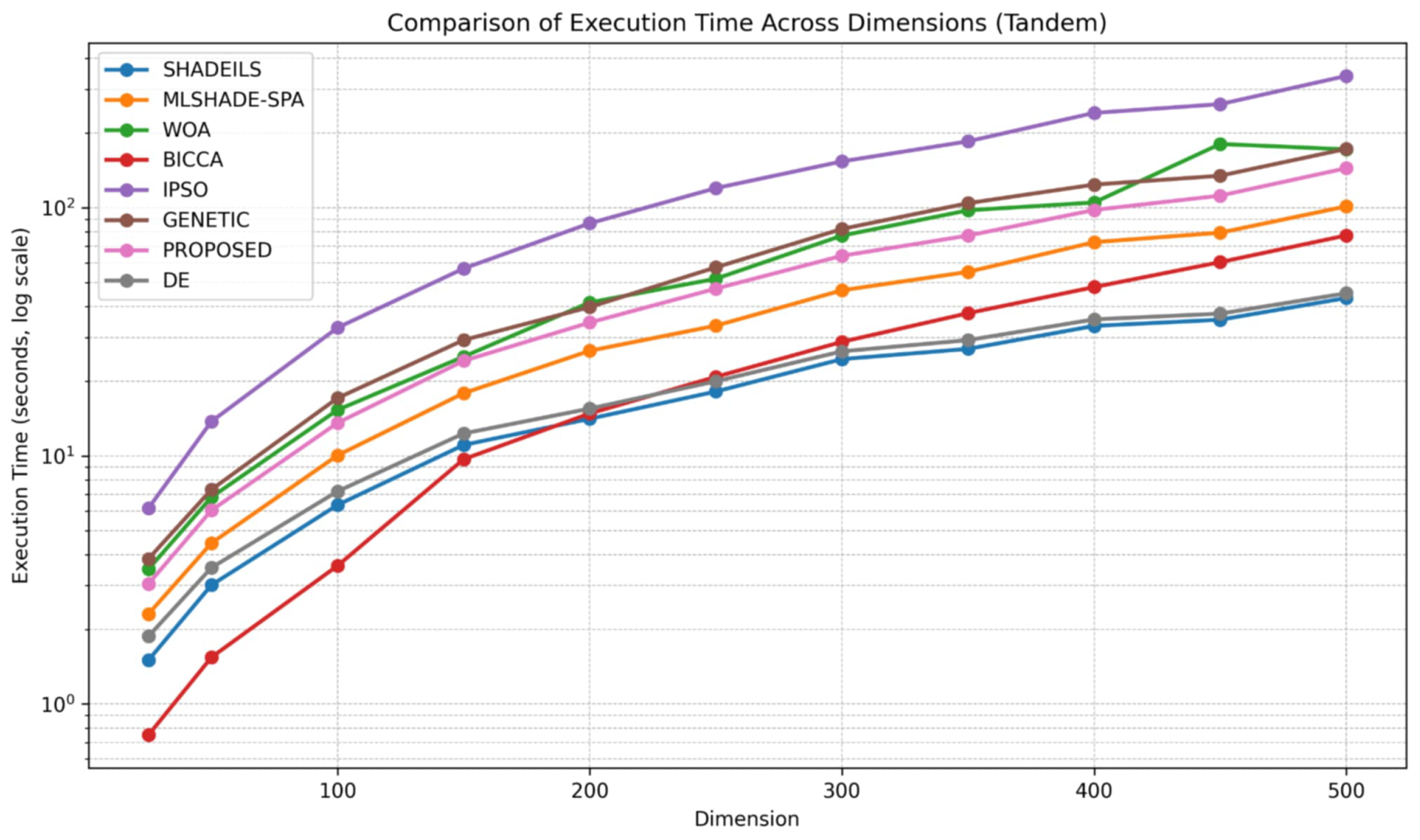

- Tandem Space Trajectory (MGA-1DSM, EVEEJ + 2 × Saturn)Vars (): .Objective:Notes: decreases (log-like) in ( km/s floor); leg/branch costs decrease with TOF.The figures corresponding to the Tandem scenario illustrate the behavior of the evaluated algorithms in terms of function calls and execution time as the problem dimension increases. As expected, higher dimensionality leads to increased computational effort for all methods; however, notable differences in scalability can be observed.In the Tandem case, as shown in Figure 12, the proposed algorithm demonstrates stable and consistent behavior across all tested dimensions, maintaining a relatively low number of function calls. Its performance remains competitive with the most efficient approaches and is clearly more scalable than methods such as the GA, BICCA and IPSO, which exhibit a rapid increase in function calls as dimensionality grows. The controlled growth observed for the proposed method indicates effective search dynamics and an appropriate balance between exploration and exploitation in large-scale settings.The execution time results for the Tandem scenario, presented in Figure 13, further confirm these observations. The proposed algorithm shows smooth and predictable scaling with increasing problem dimensions, avoiding the steep runtime growth observed in more computationally demanding methods. Although execution time naturally increases for larger dimensions, the rate of increase remains moderate, suggesting that the internal computational cost of the proposed approach is well managed and suitable for practical large-scale applications in the Tandem scenario.Across both Tandem and GasCycle scenarios, the proposed algorithm demonstrates consistent scalability in terms of both function evaluations and execution time. Its stable behavior under increasing dimensionality indicates that it represents a reliable and efficient alternative for large-scale optimization problems, without incurring excessive computational cost.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Legat, B.; Dowson, O.; Garcia, J.D.; Lubin, M. MathOptInterface: A data structure for mathematical optimization problems. Informs J. Comput. 2022, 34, 672–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhao, D.; Heidari, A.A.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. RIME: A physics-based optimization. Neurocomputing 2023, 532, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zang, Z.; Chen, D.; Ma, X.; Liang, Y.; You, W.; Zhang, Z. Optimization and evaluation of SO2 emissions based on WRF-Chem and 3DVAR data assimilation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Optimization of crop tissue culture technology and its impact on biomolecular characteristics. Mol. Cell. Biomech. 2024, 21, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssein, E.H.; Hosney, M.E.; Mohamed, W.M.; Ali, A.A.; Younis, E.M. Fuzzy-based hunger games search algorithm for global optimization and feature selection using medical data. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 5251–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, E.; Liu, S.; Chang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Spatiotemporal co-optimization of agricultural management practices towards climate-smart crop production. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.H.; Kamel, S.; Jurado, F.; Desideri, U. Global optimization of economic load dispatch in large scale power systems using an enhanced social network search algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 156, 109719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Li, X.; Suganthan, P.N.; Yang, Z.; Weise, T. Benchmark Functions for the CEC’2010 Special Session and Competition on Large-Scale Global Optimization; Nature Inspired Computation and Applications Laboratory, USTC: Hefei, China, 2007; Volume 24, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tang, K.; Omidvar, M.N.; Yang, Z.; Qin, K. Benchmark functions for the CEC 2013 special session and competition on large-scale global optimization. Gene 2013, 7, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, D.; Herrera, F. Iterative hybridization of DE with local search for the CEC’2015 special session on large scale global optimization. In 2015 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1974–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Hao, J.; Tang, H.; Fu, X.; Zhen, Y.; Tang, K. Bridging evolutionary algorithms and reinforcement learning: A comprehensive survey on hybrid algorithms. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2024, 29, 1707–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Shang, S.; Cai, X.; Zhao, H.; Song, Y.; Xu, J. An improved differential evolution algorithm and its application in optimization problem. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 5277–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G.; Stavrou, V.N. An Intelligent Technique for Initial Distribution of Genetic Algorithms. Axioms 2023, 12, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, R.; Tian, Y.; Tang, Y. Large language models as evolution strategies. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Cicirello, V.A. Evolutionary computation: Theories, techniques, and applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Lei, X.; Lu, H.; Shi, Y. Solving multimodal optimization problems by a knowledge-driven brain storm optimization algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 150, 111105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.S.; Jasser, M.B.; Ajibade, S.S.M.; Mohamed, A.W. A systematic review on software reliability prediction via swarm intelligence algorithms. J. King-Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shami, T.M.; El-Saleh, A.A.; Alswaitti, M.; Al-Tashi, Q.; Summakieh, M.A.; Mirjalili, S. Particle swarm optimization: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 10031–10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, X.; Cui, J.; Liu, C.; Xiao, W. Modified adaptive ant colony optimization algorithm and its application for solving path planning of mobile robot. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 215, 119410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.O.; Elfadel, E.M.E.; Hashem, I.A.T.; Syed, H.J.; Ismail, M.A.; Osman, A.H.; Ahmed, A. The Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm: A Comprehensive Survey of Variants, Modifications, Applications, Developments, and Opportunities. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 3499–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, A. Multi-objective: Hybrid particle swarm optimization with firefly algorithm for feature selection with Leaky ReLU. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025, 5, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.K.; Nguyen, T.T. A review of the bat algorithm and its varieties for industrial applications. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 5327–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Diabat, A.; Mirjalili, S.; Abd Elaziz, M.; Gandomi, A.H. The arithmetic optimization algorithm. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 376, 113609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential Evolution—A Simple and Efficient Adaptive Scheme for Global Optimization over Continuous Spaces; International Computer Science Institute: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, X.; Xia, A. An enhanced multi-objective differential evolution algorithm for dynamic environmental economic dispatch of power system with wind power. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babanezhad, M.; Behroyan, I.; Nakhjiri, A.T.; Marjani, A.; Rezakazemi, M.; Shirazian, S. High-performance hybrid modeling chemical reactors using differential evolution based fuzzy inference system. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, D.; Yu, F.; Heidari, A.A.; Ru, J.; Chen, H.; Mafarja, M.; Turabieh, H.; Pan, Z. Performance optimization of differential evolution with slime mould algorithm for multilevel breast cancer image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 138, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Chong, S.Y. Cooperative Coevolution for Large-Scale Optimization. In Coevolutionary Computation and Its Applications; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 199–270. [Google Scholar]

- McGovarin, Z.; Engelbrecht, A.P.; Ombuki-Berman, B.M. Stochastic Grouping and Subspace-Based Initialization in Decomposition and Merging Cooperative Particle Swarm Optimization for Large-Scale Optimization Problems. In Proceedings of the 37th Canadian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Guelph, ON, Canada, 27–31 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Liao, Y.; Peng, H.; Kang, L.; Zeng, Y. A high-dimensional feature selection algorithm via fast dimensionality reduction and multi-objective differential evolution. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 94, 101899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Du, K.J.; Zhan, Z.H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. Distributed differential evolution with adaptive resource allocation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 53, 2791–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, A.T.; Bello-Salau, H.; Onumanyi, A.J.; Mu’azu, M.B.; Adedokun, E.A.; Salawudeen, A.T.; Adekale, A.D. A particle swarm and smell agent-based hybrid algorithm for enhanced optimization. Algorithms 2024, 17, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tan, Y. SF-FWA: A self-adaptive fast fireworks algorithm for effective large-scale optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 80, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, H. An agent-assisted heterogeneous learning swarm optimizer for large-scale optimization. Swarm Evol. 2024, 89, 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Zhan, Z.H.; Tan, K.C.; Zhang, J. Dual differential grouping: A more general decomposition method for large-scale optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 53, 3624–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.V.; Storn, R.M.; Lampinen, J.A. Differential Evolution: A Practical Approach to Global Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G.; Tzallas, A.; Karvounis, E. Modifications for the differential evolution algorithm. Symmetry 2022, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.J.D. A tolerant algorithm for linearly constrained optimization calculations. Math. Program. 1989, 45, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, G.; Neri, F. Enhancing distributed differential evolution with multicultural migration for global numerical optimization. Inf. Sci. 2013, 247, 72–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Kaelo, P. Improved particle swarm algorithms for global optimization. Appl. Math. Comput. 2008, 196, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, H.; Ceylan, R. A PSO based approach: Scout particle swarm algorithm for continuous global optimization problems. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2019, 6, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siarry, P.; Berthiau, G.; Durdin, F.; Haussy, J. Enhanced simulated annealing for globally minimizing functions of many-continuous variables. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. (TOMS) 1997, 23, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTorre, A.; Molina, D.; Osaba, E.; Poyatos, J.; Del Ser, J.; Herrera, F. A prescription of methodological guidelines for comparing bio-inspired optimization algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 67, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoulos, I.G.; Charilogis, V.; Kyrou, G.; Stavrou, V.N.; Tzallas, A. OPTIMUS: A Multidimensional Global Optimization Package. J. Open Source Softw. 2025, 10, 7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, H. A clustering method based on K-means algorithm. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Varshney, S. Analysis of k-means and k-medoids algorithm for big data. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 78, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 1, pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, H.; Zhao, M.; Hou, Y.; Kai, Z.; Sun, L.; Tan, G.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.P. Bi-space interactive cooperative coevolutionary algorithm for large scale black-box optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 97, 106798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.A.; Mohamed, A.W.; Jambi, K.M. LSHADE-SPA memetic framework for solving large-scale optimization problems. Complex Intell. Syst. 2019, 5, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, D.; LaTorre, A.; Herrera, F. SHADE with iterative local search for large-scale global optimization. In 2018 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H.; Zamani, H.; Asghari Varzaneh, Z.; Mirjalili, S. A systematic review of the whale optimization algorithm: Theoretical foundation, improvements, and hybridizations. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2023, 30, 4113–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodzicki, A.; Piekarski, M.; Jaworek-Korjakowska, J. The whale optimization algorithm approach for deep neural networks. Sensors 2021, 21, 8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Su, X.; Zhang, S.; Yan, P.; Liu, J.; Li, R. Analysis of a novel gas cycle cooler with large temperature glide for space cooling. Energy 2025, 326, 136294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthika, R.; Niranjan, S.P.; Komala Durga, B. A Survey on the tandem queueing models. Scope 2025, 14, 134–148. [Google Scholar]

| NAME | FORMULA | DIM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR | 2 | 0 | |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN | n | 0 | |

| DIFFERENT POWERS | n | 0 | |

| DISCUS | n | 0 | |

| ELLIPSOIDAL | n | 0 | |

| LLAGHER101 | n | 0 | |

| LLAGHER21 | n | 0 | |

| GRIEWANK ROSENBROCK | n | 0 | |

| GRIEWANK | n | 0 | |

| RARSTIGIN | n | 0 | |

| ROSENBROCK | n | 0 | |

| SHARP RIDGE | n | 0 | |

| SPHERE | n | 0 | |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL | n | 0 | |

| ZAKHAROV | n | 0 |

| PARAMETER | MEANING | VALUE |

|---|---|---|

| Number of agents for all methods | 200 | |

| n | Maximum number of allowed iterations for all methods | 200 |

| Local search rate | 0.05 | |

| F | Differential weight for classic DE | |

| F | Differential weight for proposed method | 0.8 |

| Crossover probability | 0.9 | |

| Number of iterations used in the termination rule | 8 | |

| - | Mutation rate | 0.05 (5%) |

| - | Selection rate | 0.05 (5%) |

| - | Selection method | Roulette |

| FUNCTION | MIGRANT(T) | NUMBER(T) | RANDOM(T) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_25 | 1697 | 1743 | 1756 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_50 | 1761 | 1823 | 1828 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_100 | 1832 | 1879 | 1880 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_150 | 1867 | 1900 | 1920 |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_25 | 5893 (0.90) | 12,243 (0.90) | 12,035 (0.90) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_50 | 12,585 (0.50) | 19,529 (0.50) | 20,457 (0.50) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_100 | 16,490 (0.53) | 30,055 (0.53) | 31,465 (0.53) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_150 | 23,466 (0.27) | 40,240 (0.27) | 39,263 (0.27) |

| DISCUS_25 | 1992 | 1857 | 1896 |

| DISCUS_50 | 2060 | 1926 | 1971 |

| DISCUS_100 | 2104 | 1978 | 1989 |

| DISCUS_150 | 2144 | 2006 | 2040 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_25 | 6478 | 11,422 | 11,629 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_50 | 11,183 | 15,258 | 15,179 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_100 | 16,225 | 21,451 | 20,659 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_150 | 21,495 | 24,429 | 24,670 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 3590 | 3751 | 3958 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 6424 | 6864 | 7184 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 11,549 | 13,756 | 13,890 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 16,930 | 19,311 | 19,940 |

| LLAGHER21_25 | 2261 (0.90) | 3815 (0.90) | 6364 (0.90) |

| LLAGHER21_50 | 4503 (0.50) | 5277 (0.50) | 9643 (0.50) |

| LLAGHER21_100 | 1756 (0.53) | 1523 (0.53) | 1521 (0.53) |

| LLAGHER21_150 | 1662 (0.27) | 1521 (0.27) | 1526 (0.27) |

| LLAGHER101_25 | 2769 (0.90) | 3472 (0.90) | 5657 (0.90) |

| LLAGHER101_50 | 4890 (0.50) | 6950 (0.50) | 7454 (0.50) |

| LLAGHER101_100 | 5886 (0.53) | 6846 (0.53) | 9505 (0.53) |

| LLAGHER101_150 | 8646 (0.27) | 7701 (0.27) | 12,352 (0.27) |

| GRIEWANK _25 | 4084 | 5276 | 5145 |

| GRIEWANK _50 | 5039 | 5138 | 5729 |

| GRIEWANK _100 | 6460 | 5726 | 6002 |

| GRIEWANK _150 | 6542 | 5870 | 6164 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_25 | 4466 | 7458 | 6939 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_50 | 5325 | 9766 | 9255 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_100 | 6465 | 11,776 | 11,001 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_150 | 7272 | 13,482 | 12,543 |

| ROSENBROCK_25 | 5950 | 7824 | 7955 |

| ROSENBROCK_50 | 8963 | 13,970 | 13,057 |

| ROSENBROCK_100 | 15,930 | 23,402 | 22,348 |

| ROSENBROCK_150 | 22,135 | 32,850 | 31,562 |

| RARSTIGIN_25 | 4577 (0.90) | 9691 (0.90) | 10,242 (0.90) |

| RARSTIGIN_50 | 7746 (0.50) | 13,134 (0.50) | 12,740 (0.50) |

| RARSTIGIN_100 | 9147 (0.53) | 13,128 (0.53) | 13,184 (0.53) |

| RARSTIGIN_150 | 11,620 (0.27) | 15,105 (0.27) | 15,602 (0.27) |

| SPHERE_25 | 1481 | 1507 | 1512 |

| SPHERE_50 | 1509 | 1534 | 1539 |

| SPHERE_100 | 1524 | 1555 | 1556 |

| SPHERE_150 | 1535 | 1568 | 1567 |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 1625 (0.90) | 1642 (0.90) | 2090 (0.90) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 2300 (0.50) | 2774 (0.50) | 4021 (0.50) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 2465 (0.53) | 1598 (0.53) | 1571 (0.53) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 3143 (0.27) | 1531 (0.27) | 1521 (0.27) |

| SHARP RIDGE_25 | 5104 | 6215 | 6026 |

| SHARP RIDGE_50 | 5226 | 6850 | 7123 |

| SHARP RIDGE_100 | 5995 | 7782 | 7649 |

| SHARP RIDGE_150 | 6481 | 8112 | 8237 |

| ZAKHAROV_25 | 2185 | 2752 | 2639 |

| ZAKHAROV_50 | 3027 | 4063 | 3864 |

| ZAKHAROV_100 | 5572 | 6265 | 5634 |

| ZAKHAROV_150 | 6304 | 7574 | 7553 |

| 387,335 (0.85) | 527,444 (0.85) | 543,201 (0.85) |

| FUNCTION | MIGRANT(T) | MIGRANT(R) | RANDOM(T) | RANDOM(R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_25 | 1697 | 2174 | 1756 | 2162 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_50 | 1761 | 2212 | 1828 | 2162 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_100 | 1832 | 2177 | 1880 | 2192 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_150 | 1867 | 2206 | 1920 | 2174 |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_25 | 5893 (0.90) | 15,894 (0.90) | 12,035 (0.90) | 11,921 (0.90) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_50 | 12,585 (0.50) | 50,438 (0.50) | 20,457 (0.50) | 20,542 (0.50) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_100 | 16,490 (0.53) | 59,214 (0.53) | 31,465 (0.53) | 34,570 (0.53) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_150 | 23,466 (0.27) | 77,590 (0.27) | 39,263 (0.27) | 54,663 (0.27) |

| DISCUS_25 | 1992 | 2588 | 1896 | 2542 |

| DISCUS_50 | 2060 | 2601 | 1971 | 2552 |

| DISCUS_100 | 2104 | 2553 | 1989 | 2617 |

| DISCUS_150 | 2144 | 2608 | 2040 | 2591 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_25 | 6478 | 13,918 | 11,629 | 14,477 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_50 | 11,183 | 20,100 | 15,179 | 20,064 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_100 | 16,225 | 27,396 | 20,659 | 29,408 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_150 | 21,495 | 35,710 | 24,670 | 35,070 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 3590 | 6424 | 3958 | 5932 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 6424 | 11,704 | 7184 | 10,585 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 11,549 | 20,736 | 13,890 | 20,887 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 16,930 | 29,835 | 19,940 | 28,265 |

| LLAGHER21_25 | 2261 (0.90) | 5412 (0.90) | 6364 (0.90) | 2891 (0.90) |

| LLAGHER21_50 | 4503 (0.50) | 11,988 (0.50) | 9643 (0.50) | 3311 (0.50) |

| LLAGHER21_100 | 1756 (0.53) | 1565 (0.53) | 1521 (0.53) | 1524 (0.53) |

| LLAGHER21_150 | 1662 (0.27) | 1490 (0.27) | 1526 (0.27) | 1520 (0.27) |

| LLAGHER101_25 | 2769 (0.90) | 5180 (0.90) | 5657 (0.90) | 3016 (0.90) |

| LLAGHER101_50 | 4890 (0.50) | 21,179 (0.50) | 7454 (0.50) | 4878 (0.50) |

| LLAGHER101_100 | 5886 (0.53) | 26,739 (0.53) | 9505 (0.53) | 4507 (0.53) |

| LLAGHER101_150 | 8646 (0.27) | 46,866 (0.27) | 12,352 (0.27) | 3400 (0.27) |

| GRIEWANK _25 | 4084 | 8148 | 5145 | 9902 |

| GRIEWANK _50 | 5039 | 7894 | 5729 | 5203 |

| GRIEWANK _100 | 6460 | 9083 | 6002 | 4145 |

| GRIEWANK _150 | 6542 | 9154 | 6164 | 4075 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_25 | 4466 | 11,510 | 6939 | 17,429 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_50 | 5325 | 14,658 | 9255 | 24,666 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_100 | 6465 | 15,890 | 11,001 | 34,019 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_150 | 7272 | 17,910 | 12,543 | 39,208 |

| ROSENBROCK_25 | 5950 | 13,718 | 7955 | 15,591 |

| ROSENBROCK_50 | 8963 | 21,827 | 13,057 | 23,980 |

| ROSENBROCK_100 | 15,930 | 34,948 | 22,348 | 40,245 |

| ROSENBROCK_150 | 22,135 | 49,061 | 31,562 | 53,073 |

| RARSTIGIN_25 | 4577 (0.90) | 11,276 (0.90) | 10,242 (0.90) | 9910 (0.90) |

| RARSTIGIN_50 | 7746 (0.50) | 26,967 (0.50) | 12,740 (0.50) | 14,234 (0.50) |

| RARSTIGIN_100 | 9147 (0.53) | 27,639 (0.53) | 13,184 (0.53) | 16,666 (0.53) |

| RARSTIGIN_150 | 11,620 (0.27) | 34,865 (0.27) | 15,602 (0.27) | 19,135 (0.27) |

| SPHERE_25 | 1481 | 1620 | 1512 | 1627 |

| SPHERE_50 | 1509 | 1641 | 1539 | 1634 |

| SPHERE_100 | 1524 | 1635 | 1556 | 1644 |

| SPHERE_150 | 1535 | 1644 | 1567 | 1639 |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 1625 (0.90) | 2073 (0.90) | 2090 (0.90) | 1750 (0.90) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 2300 (0.50) | 5937 (0.50) | 4021 (0.50) | 1664 (0.50) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 2465 (0.53) | 6546 (0.53) | 1571 (0.53) | 1523 (0.53) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 3143 (0.27) | 11487 (0.27) | 1521 (0.27) | 1520 (0.27) |

| SHARP RIDGE_25 | 5104 | 10,153 | 6026 | 11,776 |

| SHARP RIDGE_50 | 5226 | 11,108 | 7123 | 12,123 |

| SHARP RIDGE_100 | 5995 | 11,592 | 7649 | 12,704 |

| SHARP RIDGE_150 | 6481 | 12,053 | 8237 | 12,395 |

| ZAKHAROV_25 | 2185 | 3941 | 2639 | 4605 |

| ZAKHAROV_50 | 3027 | 8972 | 3864 | 7963 |

| ZAKHAROV_100 | 5572 | 23,782 | 5634 | 14,514 |

| ZAKHAROV_150 | 6304 | 25,370 | 7553 | 16,240 |

| 387,335 (0.85) | 962,599 (0.85) | 543,201 (0.85) | 767,225 (0.85) |

| FUNCTION | MIGRANT(K) | MIGRANT(U) | RANDOM(K) | RANDOM(U) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_25 | 1697 | 1738 | 1756 | 1792 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_50 | 1761 | 1792 | 1828 | 1832 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_100 | 1832 | 1866 | 1880 | 1891 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_150 | 1867 | 1890 | 1920 | 1920 |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_25 | 5893 (0.90) | 12,818 (0.03) | 12,035 (0.90) | 28,865 (0.03) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_50 | 12,585 (0.50) | 23,622 (0.03) | 20,457 (0.50) | 34,379 (0.03) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_100 | 16,490 (0.53) | 41,526 (0.03) | 31,465 (0.53) | 70,319 (0.03) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_150 | 23,466 (0.27) | 55,612 (0.03) | 39,263 (0.27) | 90,211 (0.03) |

| DIFFERENT POWERS_25 | 1992 | 2016 | 1896 | 1936 |

| DIFFERENT POWERS_50 | 2060 | 2077 | 1971 | 1989 |

| DIFFERENT POWERS_100 | 2104 | 2114 | 1989 | 2026 |

| DIFFERENT POWERS_150 | 2144 | 2150 | 2040 | 2058 |

| DISCUS_25 | 6478 | 7368 | 11,629 | 11,484 |

| DISCUS_50 | 11,183 | 11,666 | 15,179 | 15,789 |

| DISCUS_100 | 16,225 | 17,566 | 20,659 | 21,459 |

| DISCUS_150 | 21,495 | 22,526 | 24,670 | 24,485 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 3590 | 3640 | 3958 | 3873 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 6424 | 6399 | 7184 | 7022 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 11,549 | 12,161 | 13,890 | 13,610 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 16,930 | 17,905 | 19,940 | 19,576 |

| LLAGHER21_25 | 2261 (0.90) | 6920 (0.03) | 6364 (0.90) | 34,112 (0.03) |

| LLAGHER21_50 | 4503 (0.50) | 7904 (0.03) | 9643 (0.50) | 17,404 (0.03) |

| GALLAGHER21_100 | 1756 (0.53) | 1463 | 1521 (0.53) | 1524 (0.53) |

| GALLAGHER21_150 | 1662 (0.27) | 1463 | 1526 (0.27) | 1522 (0.27) |

| GALLAGHER101_25 | 2769 (0.90) | 6395 (0.03) | 5657 (0.90) | 27,324 (0.03) |

| GALLAGHER101_50 | 4890 (0.50) | 8204 (0.03) | 7454 (0.50) | 17,075 (0.03) |

| GALLAGHER101_100 | 5886 (0.53) | 10,816 (0.03) | 9505 (0.53) | 18,232 (0.03) |

| GALLAGHER101_150 | 8646 (0.27) | 12,129 (0.03) | 12,352 (0.27) | 17,231 (0.03) |

| GRIEWANK ROSENBROCK_25 | 4084 | 4353 | 5145 | 5434 |

| GRIEWANK ROSENBROCK_50 | 5039 | 5290 | 5729 | 5631 |

| GRIEWANK ROSENBROCK_100 | 6460 | 6211 | 6002 | 5916 |

| GRIEWANK ROSENBROCK_150 | 6542 | 6895 | 6164 | 6113 |

| GRIEWANK_25 | 4466 | 4818 | 6939 | 7697 |

| GRIEWANK_50 | 5325 | 7163 | 9255 | 11,056 |

| GRIEWANK_100 | 6465 | 9992 | 11,001 | 15,311 |

| GRIEWANK_150 | 7272 | 12,350 | 12,543 | 19,125 |

| RARSTIGIN_25 | 5950 | 5909 (0.03) | 7955 | 8447 (0.03) |

| RARSTIGIN_50 | 8963 | 10,112 (0.03) | 13,057 | 13,669 (0.03) |

| RARSTIGIN_100 | 15,930 | 16,541 (0.03) | 22,348 | 23,760 (0.03) |

| RARSTIGIN_150 | 22,135 | 23,181 (0.03) | 31562 | 33,005 (0.03) |

| ROSENBROCK_25 | 4577 (0.90) | 9432 | 10,242 (0.90) | 18,663 |

| ROSENBROCK_50 | 7746 (0.50) | 11,863 | 12,740 (0.50) | 27,806 |

| ROSENBROCK_100 | 9147 (0.53) | 15,307 | 13,184 (0.53) | 28,064 |

| ROSENBROCK_150 | 11,620 (0.27) | 18,904 | 15,602 (0.27) | 43,292 |

| SHARP RIDGE_25 | 1481 | 1498 | 1512 | 1528 |

| SHARP RIDGE_50 | 1509 | 1516 | 1539 | 1548 |

| SHARP RIDGE_100 | 1524 | 1531 | 1556 | 1559 |

| SHARP RIDGE_150 | 1535 | 1548 | 1567 | 1565 |

| SPHERE_25 | 1625 (0.90) | 2733 | 2090 (0.90) | 7103 |

| SPHERE_50 | 2300 (0.50) | 3173 | 4021 (0.50) | 6384 |

| SPHERE_100 | 2465 (0.53) | 3654 | 1571 (0.53) | 5873 |

| SPHERE_150 | 3143 (0.27) | 4073 | 1521 (0.27) | 5149 |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 5104 | 5014 (0.03) | 6026 | 6699 (0.03) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 5226 | 5581 (0.03) | 7123 | 7205 (0.03) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 5995 | 6091 (0.03) | 7649 | 7893 (0.03) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 6481 | 5996 (0.03) | 8237 | 8037 (0.03) |

| ZAKHAROV_25 | 2185 | 2283 | 2639 | 2797 |

| ZAKHAROV_50 | 3027 | 2901 | 3864 | 3743 |

| ZAKHAROV_100 | 5572 | 4122 | 5634 | 5936 |

| ZAKHAROV_150 | 6304 | 5282 | 7553 | 7460 |

| 387,335 (0.85) | 529,063 (0.71) | 543,201 (0.85) | 844,408 (0.69) |

| FUNCTION | MIGRANT (0.005) | MIGRANT (0.01) | MIGRANT (0.03) | MIGRANT (0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_25 | 1441 | 1472 | 1603 | 1697 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_50 | 1582 | 1522 | 1674 | 1761 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_100 | 1516 | 1552 | 1699 | 1832 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_150 | 1536 | 1560 | 1726 | 1867 |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_25 | 2035 (0.90) | 2502 (0.90) | 4323 (0.90) | 5893 (0.90) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_50 | 3468 (0.50) | 4319 (0.50) | 8496 (0.50) | 12,585 (0.50) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_100 | 4179 (0.53) | 5700 (0.53) | 10,756 (0.53) | 16,490 (0.53) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_150 | 5900 (0.27) | 7794 (0.27) | 14,818 (0.27) | 23,466 (0.27) |

| DISCUS_25 | 1525 | 1616 | 1841 | 1992 |

| DISCUS_50 | 1615 | 1658 | 1919 | 2060 |

| DISCUS_100 | 1578 | 1655 | 1979 | 2104 |

| DISCUS_150 | 1590 | 1663 | 1987 | 2144 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_25 | 2296 | 2855 | 4661 | 6478 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_50 | 3011 | 3807 | 7580 | 11,183 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_100 | 3827 | 5693 | 11,214 | 16,225 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_150 | 4736 | 7158 | 15,238 | 21,495 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 1765 | 2011 | 2940 | 3590 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 2235 | 2844 | 4854 | 6424 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 3234 | 4557 | 9215 | 11,549 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 4581 | 6620 | 12,510 | 16,930 |

| GALLAGHER21_25 | 1751 (0.90) | 1804 (0.90) | 2049 (0.90) | 2261 (0.90) |

| GALLAGHER21_50 | 2842 (0.50) | 3012 (0.50) | 3765 (0.50) | 4503 (0.50) |

| GALLAGHER21_100 | 1432 (0.53) | 1470 (0.53) | 1609 (0.53) | 1756 (0.53) |

| GALLAGHER21_150 | 1434 (0.27) | 1455 (0.27) | 1554 (0.27) | 1662 (0.27) |

| GALLAGHER101_25 | 1778 (0.90) | 1896 (0.90) | 2359 (0.90) | 2769 (0.90) |

| GALLAGHER101_50 | 3287 (0.50) | 3470 (0.50) | 4186 (0.50) | 4890 (0.50) |

| GALLAGHER101_100 | 3550 (0.53) | 3804 (0.53) | 4851 (0.53) | 5886 (0.53) |

| GALLAGHER101_150 | 4726 (0.27) | 5208 (0.27) | 6959 (0.27) | 8646 (0.27) |

| GRIEWANK _25 | 1858 | 2102 | 3137 | 4084 |

| GRIEWANK _50 | 2154 | 2407 | 3859 | 5039 |

| GRIEWANK _100 | 2135 | 2688 | 4542 | 6460 |

| GRIEWANK _150 | 2298 | 2937 | 4919 | 6542 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_25 | 1840 | 2116 | 3292 | 4466 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_50 | 2091 | 2661 | 4199 | 5325 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_100 | 2343 | 2969 | 4868 | 6465 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_150 | 2512 | 3295 | 5496 | 7272 |

| ROSENBROCK_25 | 1964 | 2450 | 4091 | 5950 |

| ROSENBROCK_50 | 2675 | 3619 | 6578 | 8963 |

| ROSENBROCK_100 | 3616 | 5278 | 10,570 | 15,930 |

| ROSENBROCK_150 | 5326 | 7819 | 15,572 | 22,135 |

| RARSTIGIN_25 | 1831 (0.90) | 2135 (0.90) | 3346 (0.90) | 4577 (0.90) |

| RARSTIGIN_50 | 2858 (0.50) | 3334 (0.50) | 5664 (0.50) | 7746 (0.50) |

| RARSTIGIN_100 | 2941 (0.53) | 3697 (0.53) | 6336 (0.53) | 9147 (0.53) |

| RARSTIGIN_150 | 3997 (0.27) | 4826 (0.27) | 8275 (0.27) | 11,620 (0.27) |

| SPHERE_25 | 1402 | 1411 | 1455 | 1481 |

| SPHERE_50 | 1537 | 1444 | 1475 | 1509 |

| SPHERE_100 | 1463 | 1454 | 1489 | 1524 |

| SPHERE_150 | 1481 | 1469 | 1494 | 1535 |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 1513 (0.90) | 1526 (0.90) | 1576 (0.90) | 1625 (0.90) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 2136 (0.50) | 2155 (0.50) | 2229 (0.50) | 2300 (0.50) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 2286 (0.53) | 2308 (0.53) | 2389 (0.53) | 2465 (0.53) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 2914 (0.27) | 2938 (0.27) | 3040 (0.27) | 3143 (0.27) |

| SHARP RIDGE_25 | 1934 | 2269 | 3453 | 5104 |

| SHARP RIDGE_50 | 2130 | 2680 | 4042 | 5226 |

| SHARP RIDGE_100 | 2190 | 2718 | 4489 | 5995 |

| SHARP RIDGE_150 | 2350 | 3107 | 5131 | 6481 |

| ZAKHAROV_25 | 1570 | 1635 | 1912 | 2185 |

| ZAKHAROV_50 | 1714 | 1884 | 2505 | 3027 |

| ZAKHAROV_100 | 2428 | 2677 | 4597 | 5572 |

| ZAKHAROV_150 | 2090 | 2314 | 4721 | 6304 |

| 148,027 (0.85) | 178,999 (0.85) | 289,106 (0.85) | 387,335 (0.85) |

| FUNCTION | BICCA | MLSHADESPA | SHADE_ILS | DE | GA | WOA | IPSO | PROPOSED |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_25 | 5130 | 950 | 452 | 4439 | 2208 | 2641 | 2120 | 1697 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_50 | 10,097 | 994 | 558 | 18,104 | 2230 | 5700 | 2167 | 1761 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_100 | 20,178 | 989 | 748 | 15,246 | 2231 | 5785 | 2179 | 1832 |

| ATTRACTIVE SECTOR_150 | 30,259 | 1047 | 959 | 6646 | 2232 | 9248 | 2196 | 1867 |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_25 | 5144 (0.33) | 9420 (0.90) | 2093 (0.90) | 1466 (0.90) | 12,979 (0.90) | 15,048 (0.93) | 12,115 (0.90) | 5893 (0.90) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_50 | 10,345 (0.03) | 18,003 (0.50) | 3440 (0.50) | 1894 (0.50) | 20,711 (0.50) | 58,557 (0.77) | 30,866 (0.50) | 12,585 (0.50) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_100 | 20,676 (0.03) | 30,652 (0.53) | 5428 (0.53) | 2020 (0.53) | 29,121 (0.53) | 43,001 (0.97) | 39,680 (0.53) | 16,490 (0.53) |

| BUCHE RASTRIGIN_150 | 30,894 (0.03) | 47,160 (0.27) | 7663 (0.27) | 2511 (0.27) | 37,696 (0.27) | 54,641 | 53,060 (0.27) | 23,466 (0.27) |

| DISCUS_25 | 5125 | 1365 | 536 | 4255 | 2656 | 3006 | 2452 | 1992 |

| DISCUS_50 | 10,101 | 1425 | 642 | 10,297 | 2663 | 6310 | 2498 | 2060 |

| DISCUS_100 | 20,189 | 1402 | 826 | 8284 | 2631 | 5835 | 2523 | 2104 |

| DISCUS_150 | 30,265 | 1487 | 1042 | 8548 | 2620 | 8227 | 2548 | 2144 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_25 | 5144 | 13,007 | 2644 | 4786 | 14,495 | 14,921 | 13,313 | 6478 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_50 | 10,389 | 20,029 | 3860 | 14,391 | 20,539 | 35,828 | 19,839 | 11,183 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_100 | 20,644 | 27,859 | 5450 | 7355 | 28,413 | 52,081 | 28,379 | 16,225 |

| DIFFERENTPOWERS_150 | 30,877 | 36,894 | 7059 | 6266 | 33,569 | 93,074 | 36,287 | 21,495 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 5139 (0.87) | 4227 | 1117 | 4161 | 5955 | 7299 | 6375 | 3590 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 10,247 | 9146 | 2178 | 16,624 | 10,892 | 19,281 | 11,641 | 6424 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 20,492 | 18,062 | 3966 | 12,708 | 20,202 | 38,501 | 20,736 | 11,549 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 30,708 | 26,835 | 5993 | 21,936 | 36,236 | 63,093 | 29,414 | 16,930 |

| GALLAGHER21_25 | 5122 (0.46) | 1304 (0.90) | 503 (0.90) | 4180 (0.90) | 3346 (0.90) | 9210 (0.90) | 3605 (0.90) | 2261 (0.90) |

| GALLAGHER21_50 | 10,119 (0.03) | 1757 (0.50) | 701 (0.50) | 7938 (0.50) | 3192 (0.50) | 35,580 (0.50) | 8866 (0.50) | 4503 (0.50) |

| GALLAGHER21_100 | 20,167 | 392 (0.53) | 637 (0.53) | 1323 (0.53) | 1593 (0.53) | 1950 (0.53) | 5363 (0.53) | 1756 (0.53) |

| GALLAGHER21_150 | 30,248 | 385 (0.27) | 825 (0.27) | 1313 (0.27) | 1582 (0.27) | 1738 (0.27) | 2050 (0.27) | 1662 (0.27) |

| GALLAGHER101_25 | 5117 (0.07) | 1270 | 501 (0.90) | 3625 (0.90) | 3340 (0.90) | 7664 (0.90) | 3473 (0.90) | 2769 (0.90) |

| GALLAGHER101_50 | 10,114 (0.03) | 1396 | 634 (0.50) | 18,470 (0.50) | 7134 (0.50) | 38,817 (0.50) | 8796 (0.50) | 4890 (0.50) |

| GALLAGHER101_100 | 20,193 (0.03) | 1868 | 901 (0.53) | 14,700 (0.53) | 5794 (0.53) | 39,700 (0.53) | 9257 (0.53) | 5886 (0.53) |

| GALLAGHER101_150 | 30,269 (0.03) | 1922 | 1127 (0.27) | 24,214 (0.27) | 7210 (0.27) | 36,525 (0.27) | 14076 (0.27) | 8646 (0.27) |

| GRIEWANK _25 | 5173 (0.70) | 7828 | 1811 | 4123 (0.97) | 9733 | 10,166 | 9454 | 4084 |

| GRIEWANK _50 | 10,138 | 3434 | 1061 | 17,524 (0.93) | 5410 | 18,966 | 9827 | 5039 |

| GRIEWANK _100 | 20,208 | 2825 | 1124 | 14,809 | 4982 | 19,318 | 10,369 | 6460 |

| GRIEWANK _150 | 30,290 | 3035 | 1391 | 6335 (0.97) | 5221 | 28,823 | 10,741 | 6542 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_25 | 5180 | 14,086 | 3132 | 3238 | 17,038 | 10,630 | 9698 | 4466 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_50 | 10,362 | 20,021 | 4319 | 16,379 | 23,217 | 22,912 | 11,610 | 5325 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_100 | 20,462 | 23,913 | 4925 | 11,375 | 31,195 | 24,543 | 13,409 | 6465 |

| GRIEWANK_ROSENBROCK_150 | 30,604 | 29,813 | 6080 | 4446 | 37,364 | 33,948 | 15,075 | 7272 |

| ROSENBROCK_25 | 5163 | 12,518 | 2793 | 3543 | 15,493 | 13,642 | 13,642 | 5950 |

| ROSENBROCK_50 | 10,451 | 21,195 | 4555 | 12,085 | 24,602 | 33,038 | 22,317 | 8963 |

| ROSENBROCK_100 | 20,785 | 35,136 | 7151 | 6038 | 39,496 | 48,451 | 36,400 | 15,930 |

| ROSENBROCK_150 | 31,103 | 50,850 | 10,669 | 4203 | 53,211 | 75,425 | 50,281 | 22,135 |

| RARSTIGIN_25 | 5139 (0.36) | 7826 (0.90) | 1767 (0.90) | 1574 (0.90) | 9581 (0.90) | 15,530 (0.90) | 9826 (0.90) | 4577 (0.90) |

| RARSTIGIN_50 | 10,208 (0.03) | 10,741 (0.50) | 2091 (0.50) | 1895 (0.50) | 12,272 (0.50) | 41,187 (0.73) | 17,354 (0.50) | 7746 (0.50) |

| RARSTIGIN_100 | 20,358 (0.03) | 11,464 (0.53) | 2338 (0.53) | 1869 (0.53) | 2134 (0.53) | 27,383 (0.90) | 19,347 (0.53) | 9147 (0.53) |

| RARSTIGIN_150 | 30,561 (0.03) | 14,002 (0.27) | 2942 (0.27) | 2122 (0.27) | 13,990 (0.27) | 32,297 (0.93) | 27,682 (0.27) | 11,620 (0.27) |

| SPHERE_25 | 5134 | 482 | 358 | 4131 | 1689 | 2206 | 1611 | 1481 |

| SPHERE_50 | 10,088 | 500 | 459 | 18,098 | 1700 | 5111 | 1633 | 1509 |

| SPHERE_100 | 20,169 | 498 | 655 | 15,241 | 1699 | 5107 | 1639 | 1524 |

| SPHERE_150 | 30,250 | 523 | 858 | 6639 | 1700 | 7347 | 1645 | 1535 |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 5114 (0.70) | 375 (0.90) | 313 (0.90) | 1857 (0.93) | 2069 (0.90) | 1812 (0.97) | 1846 (0.90) | 1625 (0.90) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 10,086 (0.03) | 375 (0.50) | 391 (0.50) | 6493 (0.67) | 2469 (0.50) | 2541 (0.50) | 3993 (0.50) | 2300 (0.50) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 20,167 (0.03) | 377 (0.53) | 541 (0.53) | 5658 (0.53) | 1681 (0.53) | 2405 (0.53) | 3946 (0.53) | 2465 (0.53) |

| STEP ELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 30,248 (0.03) | 383 (0.27) | 695 (0.27) | 5588 (0.27) | 1673 (0.27) | 2854 (0.27) | 5065 (0.27) | 3143 (0.27) |

| SHARP RIDGE_25 | 5125 | 9281 | 2193 | 5153 | 11,536 | 11,398 | 11,371 | 5104 |

| SHARP RIDGE_50 | 10,261 | 9843 | 2284 | 18,677 | 11,818 | 19,405 | 12,550 | 5226 |

| SHARP RIDGE_100 | 20,366 | 10,190 | 2403 | 15,159 | 11,659 | 20,507 | 13,017 | 5995 |

| SHARP RIDGE_150 | 30,458 | 11,205 | 2885 | 7476 (0.97) | 11,866 | 25,983 | 13,776 | 6481 |

| ZAKHAROV_25 | 5120 | 4383 | 1177 | 1735 | 5756 | 9556 | 3449 | 2185 |

| ZAKHAROV_50 | 10,118 | 18,043 | 3584 | 2371 | 15,522 | 23,884 | 6469 | 3027 |

| ZAKHAROV_100 | 20,211 | 45,770 | 8470 | 2216 | 38,359 | 29,581 | 16,562 | 5572 |

| ZAKHAROV_150 | 30,293 | 46,497 | 9315 | 2503 | 36,399 | 32,379 | 21,273 | 6304 |

| 992,785 (0.73) | 708,659 (0.85) | 157,213 (0.85) | 478,253 (0.85) | 786,004 (0.85) | 1,371,596 (0.90) | 782,751 (0.85) | 387,335 (0.85) |

| FUNCTION | WOA | BICCA | SHADE_ILS | MLSHADESPA | DE | PROPOSED | GA | IPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELLIPSOIDAL_200 | 49,353 | 40,915 | 9635 | 35,675 | 27,985 | 22,123 | 31,875 | 30,853 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_300 | 51,152 | 61,333 | 9903 | 43,473 | 43,569 | 39,328 | 52,414 | 53,185 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_600 | 80,978 | 122,625 | 21,797 | 85,276 | 73,034 | 70,020 | 78,370 | 81,032 |

| ELLIPSOIDAL_1100 | 124,378 | 223,787 | 25,607 | 123,451 | 84,912 | 80,815 | 114,632 | 113,982 |

| FUNCTION | WOA | BICCA | SHADE_ILS | MLSHADESPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RASTRIGIN_25 | 8.42 (26.07) | 45.36 (44.73) | 8.55 (26.28) | 6.26 (19.39) |

| RASTRIGIN_50 | 27.79 (47.44) | 86.06 (23.96) | 52.16 (54.44) | 44.27 (45.56) |

| RASTRIGIN_100 | 19.07 (58.51) | 258.95 (63.67) | 70.24 (80.80) | 51.24 (55.91) |

| RASTRIGIN_150 | 12.17 (46.32) | 312.08 (68.05) | 128.81 (90.00) | 102.81 (64.24) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 1.18 (6.48) | 2107.69 (2049.63) | 387.30 (1193.21) | 387.30 (1193.21) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 0 (0) | 6975.21 (1772.99) | 3876.67 (4034.57) | 3876.67 (4034.57) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 0 (0) | 10,197.95 (1242.43) | 5232.05 (5786.36) | 5232.05 (5786.36) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 0 (0) | 9769.58 (1069.59) | 10,796.25 (6776.41) | 10,796.25 (6776.41) |

| FUNCTION | DE | PROPOSED | GA | IPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RASTRIGIN_25 | 1.49 (4.60) | 2.88 (8.8) | 5.33 (16.87) | 0.36 (1.34) |

| RASTRIGIN_50 | 23.71 (24.60) | 19.96 (21.33) | 51.30 (52.68) | 8.42 (0.09) |

| RASTRIGIN_100 | 55.12 (61.30) | 28.92 (32.80) | 62.51 (68.96) | 15.02 (16.65) |

| RASTRIGIN_150 | 132.52 (83.51) | 65.10 (41.07) | 126.06 (79.14) | 35.71 (22.56) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_25 | 0 (0) | 36.38 (131.59) | 143.05 (443.83) | 2.39 (7.74) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_50 | 0 (0) | 625.24 (709.06) | 3076.57 (3214.39) | 129.48 (159.90) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_100 | 0 (0) | 1124.16 (1293.24) | 5163.19 (5722.02) | 379.90 (481.85) |

| STEPELLIPSOIDAL_150 | 24.60 (16.03) | 2791.42 (1817.21) | 10676.31 (6679.24) | 1007.36 (777.37) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kyrou, G.; Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G. A Novel Method That Is Based on Differential Evolution Suitable for Large-Scale Optimization Problems. Foundations 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/foundations6010002

Kyrou G, Charilogis V, Tsoulos IG. A Novel Method That Is Based on Differential Evolution Suitable for Large-Scale Optimization Problems. Foundations. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/foundations6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyrou, Glykeria, Vasileios Charilogis, and Ioannis G. Tsoulos. 2026. "A Novel Method That Is Based on Differential Evolution Suitable for Large-Scale Optimization Problems" Foundations 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/foundations6010002

APA StyleKyrou, G., Charilogis, V., & Tsoulos, I. G. (2026). A Novel Method That Is Based on Differential Evolution Suitable for Large-Scale Optimization Problems. Foundations, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/foundations6010002