Abstract

Background/Objectives: Childhood trauma has a documented impact on development, and may also affect functioning and well-being in transition-age youth (TAY). There is a need to explore approaches, such as trauma-informed care (TIC), to enhance the services provided during the transition to adulthood. The objective of this scoping review was to explore the extent of the literature on the potential of TIC for supporting TAY. Methods: We focused on initiatives grounded in TIC to support TAY between the ages of 14 and 25 who have histories of trauma. The search strategy involved nine databases and the gray literature. The titles, abstracts, and full text were screened in duplicate by reviewers, and then data were extracted. Results: A total of 19 references were included and classified into three categories: (1) importance of TIC to support TAY (k = 5); (2) description of TIC initiatives (k = 6); and (3) evaluation of TIC initiatives supporting TAY (k = 2). Seven references were classified into more than one category. The references documented 10 TIC models or initiatives, half of which were evaluated and showed promising results. Important components of TIC initiatives supporting TAY included staff training and support; collaborative and multidisciplinary work; systemic changes; addressing trauma and its impacts; and a strength-based and youth-focused approach. Conclusions: The review emphasizes the importance of acknowledging and responding to trauma and its impact in TAY and advances the core components of TIC in the context of the TA, including its systemic nature. Although we cannot conclude that TIC is effective in supporting the TA at the moment—given that the literature is still in its early stages—the review shows that it is at least promising. Limitations, as well as future lines of work are discussed.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, poverty, and exposure to community violence or peer victimization, are undoubtedly common [1], as reiterated in a recent meta-analysis from Madigan et al. (2023) [2]. The rates are even higher among child welfare or foster care samples [3,4]. Collin-Vézina et al. (2011) and Cyr et al. [4] found that approximately half of children and youth in these samples disclosed at least four forms of maltreatment (sexual, physical, or psychological abuse and physical or psychological neglect) or victimization (i.e., conventional crime, maltreatment, peer and sibling victimization, sexual victimization, and witnessing and other exposure to violence). Children and youth in child welfare or foster care also show clinical levels of depression, anger, post-traumatic stress, and dissociation [3], and system-induced trauma from being separated from family, friends, and community, placement instability, or violence [5,6,7]. This underscores the relevance of approaches that address trauma and retraumatization in children and youth, hereafter referred to as “trauma-exposed” or “with histories of trauma”.

While there is no consensus on the definition of trauma, the one from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is widely recognized and accepted: “trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being” (p. 7) [5]. Trauma has been associated with mental health issues, social-emotional difficulties, cognitive and language problems, educational challenges, as well as difficulties related to identity and self-esteem throughout development, including during the transition to adulthood (TA) [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The TA is a developmental period around the age of majority that is characterized by change, exploration, and challenges in multiple interrelated aspects of development and functioning, when the ultimate goal is to achieve autonomy [14,15,16]. The effects of trauma on development may affect functioning and well-being in transition-age youth (TAY, that is, youth who are around the age of majority) [13,17,18,19,20,21]. In addition, involvement in the child welfare or the foster care systems could itself impact the TA because of the reduction in or cessation of services combined with the lack of social support from family, friends, and community in youth aging out of care [22].

1.1. TA Outcomes Among Trauma-Exposed Youth

Studies indicate that trauma-exposed TAY—including those in the child welfare or foster care systems—have poor outcomes in multiple aspects of functioning, including education and employment, economic and living situation, and mental health and social functioning [18,19,20,23,24]. For example, youth with child welfare involvement are found to have poorer educational outcomes than youth from the general population [20] or youth from low-income backgrounds [25]. A study of over 63,000 high school students revealed that youth with child welfare involvement had lower rates of high school completion and college enrollment, poorer educational performance, and greater academic challenges (i.e., special education–qualifying disabilities, school district changes, underperforming school districts) than youth from low-income backgrounds with no child welfare involvement [25]. A review showed that 38% to 83% of former foster youth have a high school diploma, 28% to 56% enroll in post-secondary education, and 17% to 49% are not in education, employment, or training [20]. Notably, when these youth are employed, the jobs are likely to be less stable with lower pay and to require low qualifications [18,20,23]. Thus, trauma-exposed youth show overall poor educational and employment outcomes.

Economic hardship and stress due to educational or employment challenges may in turn impact the living situation and mental health, and conversely, homelessness, housing instability, and mental health problems may cause additional educational and employment challenges [23]. Not having a high school diploma, having low educational attainment, and being unemployed have been found to be critical risk factors for homelessness, housing instability, and mental health issues [18,23,26]. A prospective longitudinal study of more than 2500 foster youth showed that one-third experienced at least one episode of homelessness and that one-fifth experienced housing instability at the age of 21 [27]. This study also showed that 32% (age 17) and 39% (age 19) of foster youth reported mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, or suicidal behaviors [28].

In sum, trauma-exposed youth and, to a greater extent, youth with involvement in the child welfare or foster care systems are at risk of poor TA outcomes in terms of multiple interrelated aspects of development and functioning [29], hence the need to explore initiatives aimed at supporting the TA of these youth.

1.2. Services and Programs Aiming to Support the TA

A systematic review of eight studies on the effects of services and programs aiming to support the TA yielded mixed results [30], while a meta-analysis of eight studies showed that they had significant but small effects on the outcomes related to education, employment, and living situations [31]. Program differences and methodological limitations somewhat precluded comparisons and the drawing of conclusions about the effects of the services and programs studied in this review and meta-analysis [30,31,32]. The most present and empirically supported initiatives include services and programs focusing on employment skills and integration, and providing youth support past the age of majority [17,20,23,30,33,34,35]. However, these are not consistently available in the child welfare or the foster care systems [20,30,31,33], and services should aim to prepare youth for the TA early, well before they reach the age of majority or exit the child welfare or foster care systems, and in multiple aspects of development functioning [20]. Thus, the existing services or programs—when available—may not be sufficient to fully support the TA among youth with histories of trauma, highlighting the need to explore complementary approaches, such as trauma-informed care, to enhance the services [17].

Indeed, one limitation of the programs and services reviewed is that they do not formally or specifically acknowledge and respond to trauma and its impact. Given that trauma may affect functioning and well-being during the TA, services and programs aiming to support education and employment, economic and living situations, or mental health and social functioning in TAY should address trauma [17,18,19,20]. Trauma-informed care (TIC) is a promising approach that seeks to address this limitation.

1.3. Trauma-Informed Care

TIC involves systemic changes in both organizational policies and clinical practices to “realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand potential paths for recovery; recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seek to actively resist re-traumatization” [5] (p. 9). TIC includes but is not limited to trauma-focused interventions (e.g., psychotherapy) that emphasize the assessment and treatment of trauma symptoms. TIC goes further by aiming to influence policies, procedures, and practices to formally integrate six principles (safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment; and cultural, historical, and gender issues) into services and to respond to the needs of youth with histories of trauma [5]. As such, by acknowledging and responding to trauma and its impact (e.g., mental health issues, socio-emotional difficulties, cognitive and language problems, and difficulties related to identity and self-esteem), TIC creates the necessary conditions to fully understand and respond to the needs of youth, to overcome trauma, to support youth in multiple aspects of development and functioning, and in turn, improve their education and employment, economic and living situation, and mental health and social functioning outcomes during the TA. TIC appears as a necessary additional precaution in trauma-exposed youth given their poor outcomes during the TA and that existing services or programs may not be sufficient. Thus, TIC is believed to be a promising avenue for supporting the TA in youth with trauma histories [20].

A meta-analysis showed that TIC interventions have significant and moderate effects on trauma symptoms, behaviors, and well-being in children and youth [36]. Several studies on trauma-exposed TAY recommend TIC, e.g., [21,37,38,39], and the Child Welfare League of Canada [35] affirms that foster youth must have the right to receive TIC interventions. The Child Welfare League of Canada also identified eight pillars that support the TA of foster youth. The pillars (education, employment, basic needs, social support and relationships, conduct and victimization, health and well-being, general living skills, and resilience and psychological empowerment) align with TIC principles and are corroborated in the literature as targets for supporting the TA [5,32,40]. While there is growing recognition and implementation of TIC across the child welfare and foster care systems [41], most initiatives do not specifically aim to support the TA. As mentioned above, existing services or programs aiming to support the TA, may not be sufficient, and TIC could be a complementary approach to enhance services in order to prepare youth for the TA early and in multiple aspects of development and functioning. Although some TIC programs or services specifically aiming at the TA are available, a preliminary search of databases was conducted, and no ongoing or available review was identified. This scoping review was therefore undertaken to fill this gap in knowledge and to synthesize evidence on TIC to support the TA. While there is a growing body of the literature on TIC, there is now a need to explore its potential in specific populations, here in TAY with histories of trauma. The goal of this review was to explore the extent of the literature on the potential of TIC to support the TA of trauma-exposed youth. The research questions were as follows:

- What are the existing needs and TIC approaches to specifically support the TA of trauma-exposed youth?

- What are the effects of implementing the TIC approaches?

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [42], as well as the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews [43]. A protocol was developed a priori, and though not registered, it is available on request from the corresponding author.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Participants

The review focused on TAY with histories of trauma. The review adopted an inclusive approach and targeted all youth with child welfare or foster care involvement, or with histories of ACEs or interpersonal traumatic events. Although youth aging out of the child welfare or foster care systems may face additional challenges [22], experiencing childhood trauma in itself is likely to affect the TA, so all youth with histories of trauma could require TA support and therefore were considered [17,21]. Thus, to be included in the review, references had to target youth who have been exposed to ACEs or interpersonal traumatic events (e.g., abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, poverty, peer victimization, peer isolation/rejection, and community violence exposure) or who are or have been involved with the child welfare or foster care systems. Non-interpersonal traumatic events (e.g., natural disasters, traumatic brain injuries) or war were not considered in this review to ensure a degree of homogeneity and because the impacts and mechanisms involved in those cases are somewhat different [44].

The age range for the TA period varies across studies and authors. Arnett [14] identifies emerging adulthood as the late teens to the early twenties (18 to 25 years old), whereas the Spinelli et al. [21] sample of TAY includes those aged 14 to 21 years old. Again, we adopted a more inclusive approach, and, as a general rule, we focused on youth between the ages of 14 and 25 years old. This general age band is in line with the acknowledgement that services should aim to prepare youth for the TA before they reach the age of majority, and that the TA period may exceed their twenties. The participants could be youth or other persons involved with TAY with histories of trauma (e.g., researchers, policymakers, practitioners, service providers).

2.1.2. Concept

References had to focus on outcomes related to education and employment, economic and living situation, or mental health and functioning during the TA.

2.1.3. Context

References also had to focus on services, programs, or initiatives grounded in TIC, whether they highlighted the need for a TIC approach to support the TA, described a TIC approach aimed at supporting the TA, or evaluated a TIC approach. We used the SAMHSA’s definition of TIC in which TIC involves systemic changes in both organizational policies and clinical practices to “realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand potential paths for recovery; recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seek to actively resist re-traumatization” [5] (p. 9). When a reference included an intervention focusing on the assessment and treatment of trauma symptoms (e.g., trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy [TF-CBT]) [45], it was included only if the intervention was part of a wider implementation of TIC aimed at changing organizational policies and clinical practices. Otherwise, it was not included.

2.2. Types of Sources

This scoping review did not limit the study design (e.g., observational, cross-sectional, program evaluation) or methods (qualitative, quantitative, mixed, review) to broadly explore the extent of the literature on the topic. Previous reviews that met the inclusion criteria were considered, as well as text and opinion papers and other types of references (e.g., websites, conference proceedings, government or organization documents). Only documents in English or French were included, and only one study was excluded because of the language [46]. A date limit was not applied because a previous review has not been done on the topic.

2.3. Search Strategy

The goal of the search strategy was to locate both published and unpublished documents and other types of references. A preliminary search of PsycINFO (Ovid) was undertaken to identify articles on the topic. Words in titles and abstracts, keywords, and index terms of the relevant articles identified through this preliminary search were used to develop the search strategy for PsycINFO (Ovid) with the assistance of a university librarian (see Supplementary Materials, Table S1 for the search strategy for PsycINFO). The search strategy was then adapted to eight other databases: Medline (Ovid), ERIC (ProQuest), PTSDpubs (ProQuest), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), Social Services Abstracts (ProQuest), Social Sciences Abstracts (EBSCOhost), Social Work Abstracts (EBSCOhost and Ovid), and CINAHL Plus with Full Text (EBSCOhost). The search was first conducted in the summer of 2022 and then updated in July 2023.

The reference list of all the included sources of evidence was screened for additional references. A search of relevant sources that cited the included references was also conducted. Unpublished or the gray literature was searched using keywords in Analysis & Policy observatory, Information for practice news, new scholarship & more from around the world, OpenAIRE, Publications of the Government of Canada, Policy Commons, Intergovernmental Organization Search Engine—Google, Non-governmental Organization Search Engine—Google, Bielefeld Academic Search Engine, and Google Scholar.

2.4. Sources of Evidence Selection

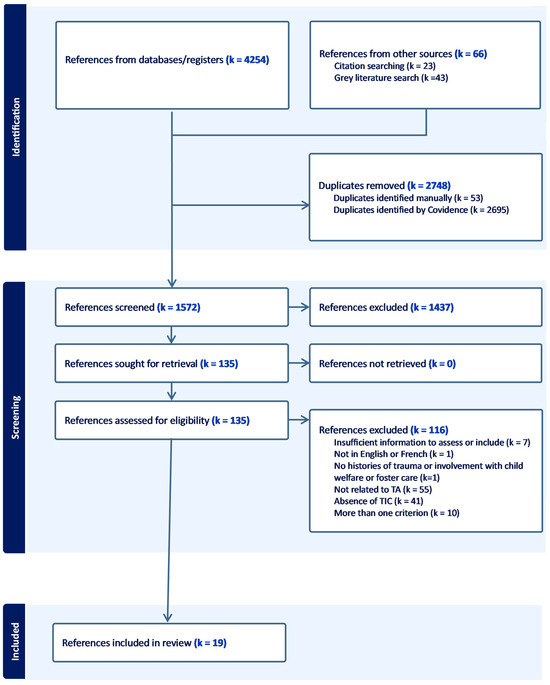

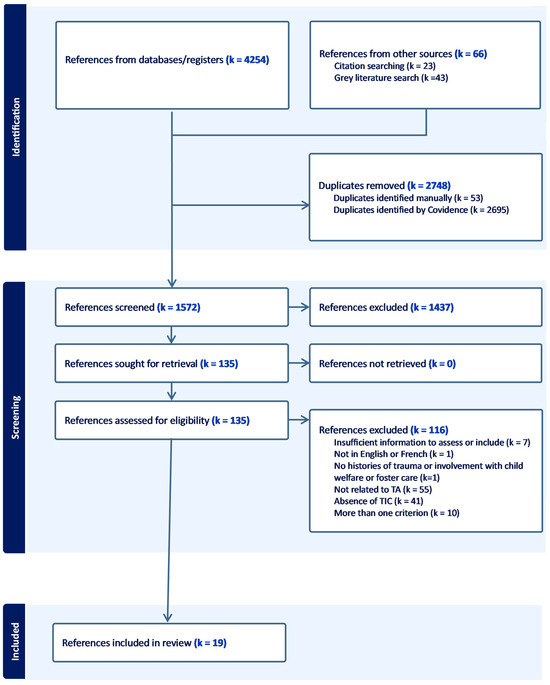

All references were uploaded into Covidence, a platform that streamlines evidence synthesis with a gold standard process [47]. Duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened in duplicate by three independent reviewers using the eligibility criteria. The reviewers were two social sciences undergraduates and one graduate student working closely with the principal investigator who specializes in trauma and TIC. The full texts of the relevant references were then retrieved and imported into Covidence. Similarly, the full texts were assessed in duplicate by two of the three independent reviewers. Any disagreements between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were resolved through discussion with the principal investigator. The reasons for exclusion were recorded at each stage. The results of the search and the selection process are reported in a flow diagram (see Figure 1) in the Results section. The search yielded 4320 references (2748 duplicates removed), from which a total of 19 were included. The inter-rater reliability indices indicated quasi-substantial agreement for title and abstract screening (ĸ = 0.59) and full-text assessment (ĸ = 0.56) [48].

2.5. Data Extraction

Data were extracted by two reviewers using a tool adapted from the tool provided by Covidence (Supplementary Materials, Table S2). The tool was adjusted to suit the objective and research questions. The draft-adapted tool was pre-tested and then revised to allow information about the following to be extracted: context of the work (e.g., country, type of document, aim), methods (e.g., data collection, sample description, outcome measurement), definitions of the main concepts (TIC, ACEs/trauma, TA), analyses, results, limitations, and the TIC services, programs, or initiatives. Data extraction was verified by the principal investigator.

2.6. Data Analysis and Presentation

References were classified into three categories based on the aim and content: (1) the need for or importance of a TIC approach to support the TA; (2) description of a TIC approach aimed at supporting the TA; or (3) the evaluation of a TIC initiative. These categories reflect the usual sequence of program development, implementation, and evaluation.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Included References

A total of 19 references were included in this scoping review (see Figure 1). About a third were peer-reviewed articles (k = 6), while most were the gray literature, including reports (k = 4), dissertations (k = 3), government or organization documents (k = 3), conference proceedings (k = 2), and a book chapter (k = 1). Most of the work was carried out in the United States (k = 12), while the rest originated from Canada (k = 3), Australia (k = 2), and the United Kingdom (k = 1) or were international (k = 1). The earliest reference dates from 2012, while the most recent is from 2021. As stated above, the references included were classified into three categories: (1) need for or importance of a TIC approach to support the TA (k = 5); (2) a description of the TIC practices and policies aimed at supporting the TA (k = 5); (3) the evaluation of a TIC initiative (k = 2); some references were classified into more than one category (k = 7). Table 1 summarizes by category the key details about and objectives and methods of the included references. Note that the information included in Table 1 is based on the information provided in the references, as well as on the category of the document.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Information, objectives, and methods of included references.

3.1.1. Need for or Importance of TIC

References in this category prioritized qualitative (k = 4) or mixed methods (k = 1) to highlight the importance of or need for a TIC approach to support the TA of youth with histories of trauma. In the qualitative studies [63,64,65,66], youth, service providers, and key stakeholders were consulted through photovoice, interviews, and focus groups. A last reference in this category was a review [56]. As for the mixed methods study [59], an online survey including self-report questionnaires and open-ended questions was administered to service providers working with TAY to assess the providers’ training needs.

3.1.2. Description of Practices and Policies

A total of five references described the TIC practices and policies for supporting the TA of youth. While some references presented models or adaptations of models grounded in TIC (Housing First for youth [54]; Therapeutic Family Model of Care [TFMC] [55]; Families Over Coming Under Stress [FOCUS] [63]), others identified trauma-informed principles or guidelines to support the TA of youth [60]. One reference reviewed models that support policy and practice related to youth aging out of care, with some including TIC principles [53].

3.1.3. Evaluation of TIC

One mixed method and one quantitative study assessed the TIC implementations. The mixed methods study [58] conducted a three-year evaluation of the LEADS (Learn—Educate—Achieve—Dream—Succeed) program to describe the characteristics and perceptions of the youth served, the types of services provided, the factors associated with success, and the TA outcomes. The quantitative study [52] used census data from the Detroit Jobs for Michigan Graduates (JMG) program to assess youth’s educational and employment achievements at three points (at intake, and during and after the program). JMG comprises three different programs, including LEAP (Learn and Earn to Achieve Potential), which itself is deployed in two models (Jobs for America’s Graduates [JAG] and Back on Track [BoT]), and advances a TIC approach.

3.1.4. Importance, Description, and Evaluation of TIC

Seven references using qualitative (k = 1), mixed (k = 3), or other types of methods (k = 3) pertained to more than one of the above reference categories. To promote the TA for youth aging out of care, Harder et al. [57] proposed principles grounded in TIC from a qualitative process that considered the implications for practice as well as research support. Similarly, a critical review of the data and a consultation of stakeholders [51] led to the identification of the best practices (which included trauma-informed ones) to support the TA of youth. One mixed methods study consulted youth through surveys, interviews, and focus groups to underline the importance of a TIC approach for supporting the TA and to evaluate youth’s experiences and outcomes [49]. Another mixed methods study used surveys and focus groups to consult youth and service providers; assess needs, strengths, barriers, and strategies while coping with trauma; and document the implementation of a TIC approach and its most effective components [67]. The other mixed methods study surveyed and interviewed staff to assess the development and implementation of the Trauma Recovery Model (TRM) [50]. Finally, the study on the LEAP initiative, which involved interviewing youth and reviewing program participation and financial data, described the implementation of the initiative, youth engagement and perspectives, and program costs [61,62].

3.2. Results of the Included References

Supplementary Materials, Table S3 presents the main results from the included references. This section synthesizes the results and focuses on the findings relevant to the research questions.

3.2.1. Evidence of the Importance of or Need for TIC to Support the TA

Although the included references indicated that services aimed at supporting the TA need to be trauma informed, Harder et al. [57] highlighted that TIC may not be present enough in services, and that staff need trauma-informed training, support, and supervision, which is in line with other accounts [59]. While youth indicated that service providers could benefit from training [67], service providers also communicated training needs related to culture, behavioral and mental health, and youth support and empowerment [59]. Other studies underlined the training needs related to trauma, its triggers and its impact [56,67], and to culturally adapted [64] and intersectionally focused services [65]. Butters [51] and Harder et al. [57] highlighted the importance of changes at the organizational and systemic level. Schubert [66] indicated that organizational changes could involve the presence of reference people within organizations to provide information and support through a trauma-informed lens.

The reviewed references highlighted the TA-related needs of youth with histories of trauma and indicated that a TIC approach could be a promising avenue for responding to those needs. The evidence showed that youth could benefit from extended services, collaboration between organizations, a strength-based approach, and support towards education, employment, housing, etc. [56,64,65].

3.2.2. Description of the Existing TIC Practices and Policies Supporting the TA

A few services, programs, and initiatives grounded in TIC are described in the literature, although they have not been assessed. Those initiatives are reviewed here as they may provide guidance on the practices and policies that may support the TA of trauma-exposed youth. Three references aimed to identify the principles or recommend the best practices [51,57,60]. Butters [51] recommended that practices should be trauma informed to acknowledge the interrelation between trauma and its impact, and to facilitate recovery [51]. Harder et al. [57] underlined 10 principles for promoting the successful TA of youth aging out of care (e.g., access to education, relationship continuity and safety nets, working through trauma, ensuring access to services). Six supplementary principles were highlighted by Kisiel et al. [60], including understanding trauma and its impact on youth and service providers (secondary traumatic stress).

The review of the Child Protection Project Committee [53] identified at least two models including TIC principles (i.e., The New Zealand’s Oranga Tamariki/Ministry for Children’s policy and The Independent Youth Housing Program). The models adopted were strength based and described as trauma informed, youth centered, holistic, and culturally adapted. The Independent Youth Housing Program, an evidence-based program, offers services ranging from rental assistance and case management to helping youth with housing and independence through a trauma-informed lens [53].

Three other models were described [54,55,63]. The first, Housing First for Youth, is used as a philosophy or a guideline by organizations working with homeless TAY [54]. It is based on TIC and aims to support youth with health and wellbeing by prioritizing the awareness and understanding of trauma, and by responding to it at a systemic level (including the organizational structure, the treatment framework, and ongoing training). The second, the TFMC, was developed to assist TAY with histories of trauma with education, employment, development, social relationships, and wellbeing [55]. It focuses on relationships between youth and carers to help youth develop interpersonal relationships and skills. The third, the FOCUS model, is a resilience-based model that assists foster families and youth in college with family functioning and routines, mental health, social skills, and understanding the reactions to stress [63]. Thus, the TIC initiatives reviewed in this section, although they have not been assessed, aim ultimately to support the TA of youth with histories of trauma.

3.2.3. Results of Evaluations of TIC Practices and Policies

The results of some evaluations provided information on implementation and on youth’s and staff’s perceptions. The LEAP program, which is deployed in two models (Jobs for America’s Graduates [JAG] and Back on Track [BoT]), seeks to address trauma in youth and help them obtain a high school equivalency or a job, gain life skills, and create a support system. The evaluation of LEAP implementation revealed a few takeaways for implementing TIC initiatives: find and retain staff to whom youth can relate; partner with organizations as a recruitment strategy for youth and as a way to connect youth to services; and flexibility when delivering programs to promote youth engagement [61,62].

The TRM, anchored in attachment, trauma, criminology, and neurology, identifies and addresses using a trauma-informed lens the needs of TAY aging out of care by establishing connections between youth and agencies and ensuring that staff understand trauma and its impact. Staff perceived that it helped youth develop confidence and self-esteem, think independently, and improve their life skills [50]. While staff found that the TRM helped, they mentioned that they lacked confidence in applying the model, which underscores the importance of training, according to Baker and Barragan [50].

As for staff training, staff expressed that time for reflection, open dialogue, and awareness of “success stories” are important [67]. Staff suggested that the following themes should also be part of trauma-informed training: understanding triggers, conflict resolution skills, and positive coping mechanisms, supporting self-regulation, de-escalation techniques, communication, staff burnout considerations, vicarious trauma, and self-care [67]. Furthermore, staff found that techniques shared during TIC training for supporting self-regulation and de-escalation were effective [6].

3.2.4. Effects of TIC Initiatives on TA Outcomes and Costs

First, the evaluation of the LEADS program indicated that intensive services were associated positively with educational progress and academic success in youth [58]. Similarly, the two evidence-based models from the LEAP initiative revealed positive youth’s educational and social functioning outcomes. More precisely, youth participating in BoT showed an increased likelihood of pursuing post-secondary education, while those involved in JAG had an increased understanding of career pathways and job credentials [61,62]. As such, most youth involved in JAG (76%) engaged in school or work in the first six months of the follow-up phase, and some obtained high school credentials. In addition, the results indicated that JAG was found to help youth create a support system and gain life skills [61,62].

Assessment of transitional living programs (TLPs) based on the Sanctuary model, a trauma-informed organizational approach [68], revealed positive outcomes in youth in terms of educational and employment outcomes, but the findings were very mixed for mental and social functioning [49]. Over a six-month period, the participating youth’s scores trended upward on the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) Adaptive Functioning scales for jobs and friends, and their positive perceptions of community living environments increased. Most youth involved in TLPs reached their employment, housing, and financial goals towards the end of the six-month study [49]. However, the assessment of the TLPs also showed an increase in social withdrawal symptoms and increasing trends for substance use and for all ASEBA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-oriented scales—though they remained in the normal range—except for the depression symptoms scale for which a decreasing trend was observed over the six-month period studied [49]. Lastly, only one study evaluated the costs of a TIC initiative (LEAP) that supports the TA. The estimated cost for all the phases ranged from CAD 5300 and CAD 7300 per youth [61,62]. However, the costs could not be compared with those of other initiatives, and cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness was not evaluated.

4. Discussion

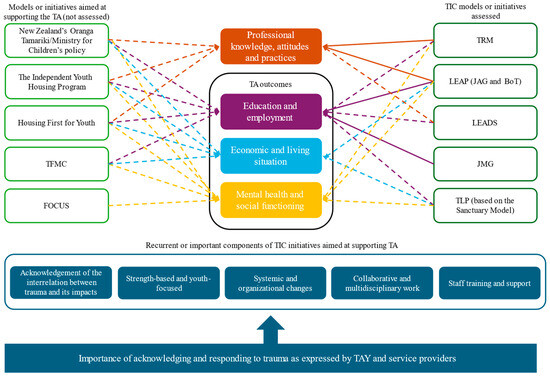

The objective of this scoping review was to explore the extent of the literature on the potential of TIC to support the TA of trauma-exposed youth. We identified 19 references (1) highlighting the need for or importance of a TIC approach to support the TA; (2) describing TIC practices and policies supporting the TA; and (3) evaluating TIC initiatives supporting the TA. We propose a schematic figure to summarize the extent of the literature on the topic (see Figure 2). References documented a total of 10 models or initiatives, half of which underwent evaluation. We also noted recurrent or important components of TIC initiatives aimed at supporting the TA that may contribute to both research and implementation initiatives: staff training and support; collaborative and multidisciplinary work; systemic and organizational changes; acknowledgment of the interrelation between trauma and its impacts; and a strength-based and youth-focused approach. These are discussed below. While the review gives an overview of the current empirical knowledge on the potential of TIC for supporting the TA, it also points out future lines of work.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the review key findings. Note: full lines indicate positive effects, whereas dashed lines indicate whether negative or null effects (for models assessed) or that the model targets that outcome but was not assessed. BoT (Back on Track); FOCUS (Families Over Coming Under Stress); JAG (Jobs for America’s Graduate); JMG (Jobs for Michigan Graduates); LEADS (Learn—Educate—Achieve—Dream—Succeed); LEAP (Learn and Earn to Achieve Potential); TAY (transition-age youth); TFMC (Therapeutic Family Model of Care); TLP (Transitional Living Program); TRM (Trauma Recovery Model).

4.1. Acknowledging and Responding to Trauma

The reviewed literature strongly supports that acknowledging and responding to trauma are essential [60], as TAY [49,63,64,65], foster families [63], and service providers [59,63,66] report that there is a need for trauma-informed services and programs to support the TA [51,54,57]. However, such services and programs may not be widely available [57], hence the need to pursue TIC implementation and integration of principles into policies, procedures, and practices. Accordingly, many of the included references indicate that youth need to receive services that acknowledge the interrelation between trauma and its impacts on development and functioning and that treat trauma symptoms in a way that is developmentally sensitive, strength-based, and youth-focused [49,50,63,64,65]. This could, in turn, positively support education and employment; economic and living situation; and mental health and social functioning during the TA [19,20]. Moreover, given that TIC actively seeks to resist re-traumatization, it could prevent or reduce system-induced trauma, which is paramount in the context where youth in child welfare or foster care may experience system-induced trauma [5,6,7].

4.2. The Definition of TIC and Its Systemic Nature: Strengths and Challenges

Although the SAMHSA’s definition of TIC is widely accepted, we uncovered that, while services and programs may define themselves as trauma informed, TIC may be inconsistently applied. In addition, it may include a variety of components or principles, making it complex to define and operationalize. Yet, the review led to the identification of “core” components in Figure 2, one of which is the systemic nature of TIC. Although this systemic nature may create challenges when it comes to operationalizing TIC into models and programs [69,70,71], the reviewed references emphasize that organizational changes are key to the systemic nature of TIC and important for supporting the TA of trauma-exposed youth [51,54,57,58]. Thus, the fact that TIC involves systemic changes in organizational policies could differentiate it from other services or programs.

Systemic and organizational changes in the context of TIC would notably encompass collaborative and multidisciplinary work [49,61,62]. The references reviewed highlighted the importance of collaboration and partnerships among stakeholders [51,62] and among different types of organizations (e.g., education and housing organizations, institution and community organizations) [56]. Partnerships could help to connect youth with services [56]. Accordingly, a review of scoping reviews [72] indicated that trusting relationships and partnerships between youth and service providers, and between service providers, are key to successful TIC initiatives. Yet, trusting service providers is a challenge for youth who have experienced system-induced trauma. Phillips et al. [7] add that multidisciplinary work is best suited to addressing youth’s complex and multiple needs related to childhood trauma. Thus, although the references reviewed draw attention to the importance of systemic and organizational changes that are part of TIC, notably through collaborative and multidisciplinary work, they also acknowledge the challenges that it poses for operationalization, and therefore for the evaluation of TIC initiatives [50,51,54,57,58].

4.3. Implementation of TIC Initiatives Through Staff Training and Support

We reviewed 10 TIC models or programs that aimed to support the TA of trauma-exposed youth, as well as three documents outlining the principles or recommendations for best practices [51,57,60]. Most models and programs involved some type of staff training to support their implementation, e.g., [50,53,54,61,62]. This is typical in the field [6,69,70,71,73] and, interestingly, could further support collaborative work and partnerships [72]. This review provides indications of what and how staff training could eventually support the TA of trauma-exposed youth. Moreover, in addition to staff training, the importance of ongoing training, supervision, and support is highlighted in many of the references reviewed [57,59,66], as well as in previous reviews on TIC [69,70].

4.4. Effects of the TIC Initiatives

While we reviewed 10 TIC models of programs, half were not evaluated, and those that were evaluated were only evaluated once [49,50,53,58,61,62]. Although we refer to “effects”, it should be noted that methods of studies preclude any causal inference between the TIC initiatives and the observed outcomes. At the moment, there is no one TIC model or program that is deemed effective or recommended for supporting the TA of trauma-exposed youth based on our review. Rather, models and programs show positive and promising effects on TA outcomes, and we have identified the key components of TIC that were found to be important (see Figure 2). Studies indicate positive effects on the youth outcomes related to education and employment and, to a lesser extent, to economic and living situations, mental health, and social functioning. Implementation initiatives also resulted in positive effects on professional knowledge, attitudes, and practices [50]. Although further evidence is needed, it is thought that changes in professional knowledge, attitudes, and practices, where staff adhere to and act upon TIC principles, could in turn have positive effects on youth [69,70]. However, some of the models and programs that have been evaluated revealed some mixed findings [61,62]. The results of evaluations are to be considered in light of the fact that the implementation of TIC initiatives is seldom described or assessed. This makes it difficult to determine whether mixed findings reflect the actual efficacy of the programs or services evaluated, or stem from issues with implementation.

4.5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This review drew upon a recent and comprehensive literature search (including the gray literature and nine databases). The extensive search for the gray literature yielded 43 additional references, of which eight were included; thus, the search for the gray literature was deemed crucial in this review to increasing our pool of references, to broadening our scope, and to incorporating the available empirical knowledge on TIC within the context of the TA. Despite its innovative research questions (synthesizing the evidence on TIC to support the TA, specifically) and strengths (e.g., search strategy, the gray literature search, duplicate screening), this scoping review also has limitations. It does not include an assessment of the methodological quality of the references, though this assessment is typically not expected in scoping reviews [42,43]. Nevertheless, the results were interpreted with the consideration of the methodology, and the methodological limitations of the references reviewed are discussed below. While screening was performed in duplicate, extraction was not. However, the tool was pre-tested, and the extraction was verified by the principal investigator in accordance with Pollock et al. [74].

The included references present strengths and limitations as well, giving indications for future studies on the topic. Some references relied on alternative methods to explore the potential of TIC for supporting the TA (e.g., the formulation of principles, clinical perspective) [57,60,63], and most did not adopt a quasi-experimental or experimental design, precluding any initial affirmations of the efficacy of TIC to support the TA, or comparisons to other services or programs. Thus, we cannot affirm whether they would have provided the same results. Such comparisons are desirable in the future, though may be premature at the moment given the state of the field in the TA context. A Hawthorne effect, where the results are influenced not by the initiative assessed, but by the participants’ awareness of the study, is not excluded, though unlikely. Indeed, TIC implementation is systemic and concerns changes in organizational policies and clinical practices, and some evaluations included measures not collected from the participants (e.g., census data); thus, the TAY may not have been fully aware of the study. Otherwise, although some studies were not experimental, they included repeated measures of outcomes [49,61,62], and the outcomes considered were multidimensional—education, life skills, employment, housing, sense of community—which is in accordance with the TA literature and reiterates the importance of multidisciplinary work when working with TAY.

We observed that some types of methods were more common for some reference categories. References discussing the importance of or need for TIC were mostly qualitative (none were solely quantitative); those describing practices or policies were mostly descriptive only; and references that assessed TIC initiatives were mostly mixed (none were solely qualitative). Although qualitative and quantitative methods are expected and deemed appropriate for exploring TAY’s needs and assessing initiatives, respectively, one can argue that we only have a partial account of the phenomena. We also note some small samples, notably in the references using qualitative methods. Although some of the studies relying on quantitative methods included large samples, the information provided on the methods or outcomes was very limited in some cases, e.g., [58].

Most of the work reviewed was recent but mainly from the U.S., which limits the generalization of the findings for other socio-cultural contexts where the systems and policies for TAY are different. Studies conducted in a variety of socio-cultural contexts are paramount, given that the TA is influenced by the context in which it occurs [75,76]. Overall, the literature would benefit from adopting quasi-experimental or experimental designs, increasing the sample sizes in studies, and providing detailed information on methods and results, as well as on TIC operationalization and implementation. The implementation and results of programs could be evaluated using the Bargeman et al. [77] term “intervention methodology” to specify to what extent they could be effective or recommended for supporting the TA of trauma-exposed youth.

In conclusion, it is interesting to note that the main findings from this review are, overall, in line with the key components of successful TIC implementation in youth settings identified by Bryson et al. [69] in a systematic review, that is: (1) the importance of organizational leadership; (2) the need to support staff; (3) the relevance of listening to individuals and families; (4) the importance of reviewing data and outcomes towards improvement; and (5) the need to align policy and practice. Our findings in the context of the TA echo these components, though the importance of families, data, and outcome reviews are themes that are less present in the reviewed references.

This paper invites a real paradigm shift in the services and programs targeted towards TAY with trauma histories. The findings from this comprehensive review will advance the importance of acknowledging and responding to trauma and its impact across all aspects of adult life (social functioning, skill development, housing, mental health, etc.). While we unfortunately cannot yet conclude that TIC is effective in supporting the TA—given that the literature is still in its early stages—it is at least promising in terms of transforming services and supporting trauma-exposed youth through the challenges that they may face during the TA. Finally, this work significantly contributes to the field of TIC by providing a comprehensive overview of the current TIC initiatives aiming to support the TA and identifying the strengths and limitations in the literature as well as future lines of research and implementation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/traumacare5020007/s1, Table S1: Search strategy for PsychINFO (Ovid); Table S2: Data extraction tool; Table S3: Main results of included references.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.-L. and V.F.; methodology, A.M.-L. and V.F.; validation, A.M.-L.; formal analysis, A.M.-L., A.L.-H. and A.d.S.-L.; investigation, A.L.-H.; resources, A.M.-L.; data curation, A.L.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.-L., A.L.-H. and A.d.S.-L.; writing—review and editing, all; supervision, A.M.-L.; project administration, A.M.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Contact the corresponding author for data supporting the reported results.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the Centre de recherche universitaire sur les jeunes et les familles (CRUJeF) for hiring undergraduate student, Noémie Girard-Bouchard, who contributed to the investigation and data curation. We thank Noémie Girard-Bouchard for her interest in and contribution to this work. We extend our gratitude to Maxime Pedneault and Marie Dumollard for their insightful comments and suggestions on previous versions of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Finkelhor, D.; Shattuck, A.; Turner, H.; Hamby, S. A Revised Inventory of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 48, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, S.; Deneault, A.-A.; Racine, N.; Park, J.; Thiemann, R.; Zhu, J.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Williamson, T.; Fearon, P.; Cénat, J.M.; et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Meta-Analysis of Prevalence and Moderators among Half a Million Adults in 206 Studies. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; Coleman; Milne, L.; Sell, J.; Daigneault, I. Trauma Experiences, Maltreatment-Related Impairments, and Resilience Among Child Welfare Youth in Residential Care. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011, 9, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, K.; Chamberland, C.; Lessard, G.; Clément, M.-È.; Wemmers, J.-A.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Gagné, M.-H.; Damant, D. Polyvictimization in a Child Welfare Sample of Children and Youths. Psychol. Violence 2012, 2, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014; p. 27.

- Matte-Landry, A.; Collin-Vézina, D. Restraint, Seclusion and Time-out among Children and Youth in Group Homes and Residential Treatment Centers: A Latent Profile Analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 109, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.R.; Hiller, R.M.; Halligan, S.L.; Lavi, I.; Macleod, J.A.A.; Wilkins, D. A Qualitative Investigation into Care-Leavers’ Experiences of Accessing Mental Health Support. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2024, 97, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haahr-Pederson, I.; Ershadi, A.E.; Hyland, P.; Hansen, M.; Perera, C.; Sheaf, G.; Bramsen, R.H.; Spitz, P.; Vallières, F. Polyvictimization and Psychopathology among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Studies Using the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 107, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.I.; Toombs, E.; Radford, A.; Boles, K.; Mushquash, C. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Executive Function Difficulties in Children: A Systematic Review. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 106, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotte, J.; Richard, M.-C.; Dufour, I.F.; Plourde, C. Les récits de vie des jeunes placés: Vécu traumatique, stratégies pour y faire face et vision d’avenir. Criminologie 2023, 56, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Kelder, R.; Van den Akker, A.L.; Geurts, H.M.; Lindauer, R.J.L.; Overbeek, G. Executive Functions in Trauma-Exposed Youth: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2018, 9, 1450595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarren-Sweeney, M. The Mental Health of Adolescents Residing in Court-Ordered Foster Care: Findings from a Population Survey. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2018, 49, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warmingham, J.M.; Handley, E.D.; Rogosch, F.A.; Manly, J.T.; Cicchetti, D. Identifying Maltreatment Subgroups with Patterns of Maltreatment Subtype and Chronicity: A Latent Class Analysis Approach. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 87, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens through the Twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Singly, F. Penser Autrement La Jeunesse. Lien Soc. Polit. 2000, 43, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supeno, E.; Bourdon, S. Bifurcations, Temporalités et Contamination Des Sphères de Vie. Parcours de Jeunes Adultes Non Diplômés et En Situation de Précarité Au Québec. Agora DébatsJeunesses 2013, 65, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Blease, K.; Kerig, P.K. Emerging Adulthood. In Child Maltreatment: A Developmental Psychopathology Approach; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.E. The Difficult Transition to Adulthood for Foster Youth in the US: Implications for the State as Corporate Parent. Soc. Policy Rep. 2009, 23, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetz, S.; O’Grady, B.; Kidd, S.; Schwan, K. Without a Home: The National Youth Homelessness Survey; Canadian Observatory on Homelessness: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; p. 126.

- Fournier, V.; Matte-Landry, A. L’insertion Professionnelle des Jeunes Ayant Vécu un Placement en Protection de la Jeunesse: Une Revue de la Portée; Centre de Recherche Universitaire sur les Jeunes et les Familles (CRUJeF); CIUSSS de la Capitale-Nationale: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2023; p. 84.

- Spinelli, T.R.; Bruckner, E.; Kisiel, C.L. Understanding Trauma Experiences and Needs through a Comprehensive Assessment of Transition Age Youth in Child Welfare. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 122, 105367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaving Care and the Transition to Adulthood: International Contributions to Theory, Research, and Practice Get Access Arrow; Mann-Feder, V.R., Goyette, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, M.E.; Goyette, M.; Dumollard, M.; Ziani, M.; Picard, J. Portrait des Jeunes Ayant Été Placés Sous les Services de la Protection de la Jeunesse et Leurs Défis en Emploi; INRS—Urbanisation Culture Société: Québec City, QC, USA, 2024; p. 54.

- Sacker, A.; Lacey, R.E.; Maughan, B.; Murray, E.T. Out-of-Home Care in Childhood and Socio-Economic Functioning in Adulthood: ONS Longitudinal Study 1971–2011. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 132, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, S.; Palmer, L. Left behind? Educational Disadvantage, Child Protection, and Foster Care. Child Abus. Negl. 2024, 149, 106680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, A. Mental Health and Homelessness Among Youth Aging Out of Foster Care: An Integrated Review. J. Stud. Res. 2022, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Goyette, M.; Blanchet, A.; Bellot, C.; Boisvert-Viens, J.; Fontaine, A. Itinérance, Judiciarisation et Marginalisation des Jeunes Ex-Placés au Québec; Chaire de Recherche sur L’évaluation des Actions Publiques à l’égard des Jeunes et des Populations Vulnérables: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2022.

- Goyette, M.; Blanchet, A.; Bellot, C. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Needs of Youth Who Leave Care; Chaire de Recherche du Canada sur L’évaluation des Actions Publiques à L’égard des Jeunes et des Populations Vulnérables: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020; p. 14.

- Pauzé, M.; Audet, M.; Pauzé, R. Soutenir l’intégration sociale de jeunes vulnérables devant composer avec les défis de transition vers l’âge adulte. Cah. Crit. Thérapie Fam. Prat. Réseaux 2020, 64, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussières, E.L.; Dubé, M.; St-Germain, A.; Lacerte, D.; Bouchard, P.; Allard, M. L’efficacité et L’efficience des Programmes D’accompagnement des Jeunes vers L’autonomie et La Préparation à la vie D’adulte; UETMISS, CIUSSS de la Capitale-Nationale, Installation Centre Jeunesse de Québec: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2015; p. 170.

- Heerde, J.A.; Hemphill, S.A.; Scholes-Balog, K.E. The Impact of Transitional Programmes on Post-Transition Outcomes for Youth Leaving out-of-Home Care: A Meta-Analysis. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, e15–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderson, H.; Smart, D.; Kerridge, G.; Currie, G.; Johnson, R.; Kaner, E.; Lynch, A.; Munro, E.; Swan, J.; McGoverrn, R. Moving from ‘What We Know Works’ to ‘What We Do in Practice’: An Evidence Overview of Implementation and Diffusion of Innovation in Transition to Adulthood for Care Experienced Young People. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2023, 28, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut National D’excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux (INESSS). Portrait des Pratiques Visant la Transition à la vie Adulte des Jeunes Résidant en Milieu de vie Substitut au Québec; Institut National D’excellence en Santé et en Services Sociaux (INESSS): Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2018; p. 120.

- Goyette, M.; Blanchet, A.; Tardif-Samson, A.; Gauthier-Davies, C. Rapport Sur Les Jeunes Participants Au Programme Qualification Jeunesse; Rapport de Recherche; Chaire de Recherche du Canada sur L’évaluation des Actions Publiques à L’égard des Jeunes et des Populations Vulnérables: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2022; p. 45.

- Child Welfare League of Canada. Equitable Standards for Transitions to Adulthood for Youth in Care; Child Welfare League of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021; p. 39.

- Zhang, S.; Conner, A.; Lim, Y.; Lefmann, T. Trauma-Informed Care for Children Involved with the Child Welfare System: A Meta-Analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 122, 105296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminer, D.; Bravo, A.J.; Mezquita, L.; Pilatti, A.; Bravo, A.J.; Conway, C.C.; Henson, J.M.; Hogarth, L.; Ibáñez, M.I.; Kaminer, D.; et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adulthood Mental Health: A Cross-Cultural Examination among University Students in Seven Countries. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 18370–18381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piel, M.H.; Lacasse, J.R. Responsive Engagement in Mental Health Services for Foster Youth Transitioning to Adulthood. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 20, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strolin-Goltzman, J.; Woodhouse, V.; Suter, J.; Werrbach, M. A Mixed Method Study on Educational Well-Being and Resilience among Youth in Foster Care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 70, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.; Park, C.; Jones, R.; Goodman, D.; Patel, M. Defining and Measuring Indicators of Successful Transitions for Youth Aging out of Child Welfare Systems: A Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2130218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matte-Landry, A.; Brend, D.; Collin-Vézina, D. Le Pouvoir Transformationnel Des Approches Sensibles Au Trauma Dans Les Services à l’enfance et à La Jeunesse Au Québec. Trav. Soc. 2023, 69, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D.; Fletcher, S.; Parslow, R.; Phelps, A.; Bryant, R.A.; McFarlane, A.; Silove, D.; Creamer, M. Trauma at the Hands of Another: Longitudinal Study of Differences in the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Profile Following Interpersonal Compared with Noninterpersonal Trauma. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, W.; Rice, S.; Cohen, J.; Murray, L.; Schley, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Bendall, S. Trauma-Focused Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) for Interpersonal Trauma in Transitional-Aged Youth. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2021, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Gisladottir, T.; Stefansdottir, R.; Johannsson, E.; Jakobsdottir, G.; Rognvaldsdottir, V. Health and Well-Being of University Students before and during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Gender Comparison. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software: Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausikaitis, A.E. Empowering Homeless Youth in Transitional Living Programs: A Transformative Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Their Transition to Adulthood. Ph.D. Dissertation, Loyola University, Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D.C.; Berragan, D.L. 1625 Independent People. Trauma Recovery Model Pilot; Evaluation Report; University of Gloucestershire: Gloucester, UK, 2020; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Butters, C. Best Practice Recommendations for Transitioning Adolescent Foster Girls; Scholarly Project; University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, J.K.; Hall, T.S.; Chua, J.C.; Ralston, K.G.; Leroux, D.F.; Belgrade, A.; Shattuck, S. Toxic Stress and Disconnection from Work and School among Youth in Detroit. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 876–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Protection Project Committee. Study Paper on Youth Aging into the Community; Study Paper 11; British Columbia Law Institute: Rochester, NY, USA, 2021; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz, S. A Safe and Decent Place to Live: Towards a Housing First Framework for Youth; Canadian Homelessness Research Network: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; p. 64.

- Gonzalez, R.; Cameron, C.; Klendo, L. The Therapeutic Family Model of Care: An Attachment and Trauma Informed Approach to Transitional Planning. Dev. Pract. Child Youth Fam. Work J. 2012, 32, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, R.E.; Westland, M.A.; Mo, E. A Trauma-Informed Care Approach to Supporting Foster Youth in Community College. In New Directions for Community Colleges; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; Volume 2018, pp. 49–58.

- Harder, A.T.; Mann-Feder, V.; Oterholm, I.; Refaeli, T. Supporting Transitions to Adulthood for Youth Leaving Care: Consensus Based Principles. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.L. 49.2 Impact of the Leads (Learn-Educate-Achieve-Dream-Succeed) Program. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jivanjee, P.; Grover, L.; Thorp, K.; Masselli, B.; Bergan, J.; Brennan, E.M. Training Needs of Peer and Non-Peer Transition Service Providers: Results of a National Survey. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 47, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiel, C.; Pauter, S.; Ocampo, A.; Stokes, C.; Bruckner, E. Trauma-Informed Guiding Principles for Working with Transition Age Youth: Provider Fact Sheet. 2021. Available online: https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/fact-sheet/trauma-informed-guiding-principles-for-working-with-transition-age-youth-provider-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation (MDRC). Lessons from the Implementation of Learn and Earn to Achieve Potential, s.d. Available online: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/LEAP%20Issue%20Focus%20Final_0.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Trekson, L.; Wasserman, K.; Ho, V. Connecting to Opportunity; Manpower Demonstration and Research Corporation (MDRC): New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Marlotte, L. 68.4 Bouncing Back: Resilience-Building in Foster Families and Youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, S101. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, P.; Standfield, R.; Saunders, B.; McCurdy, S.; Walsh, J.; Turnbull, L.; Armstrong, E. Indigenous Care Leavers in Australia: A National Scoping Study; Report; Monash University: Clayton, VIC, Australia, 2020; p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Mountz, S.; Capous-Desyllas, M.; Perez, N. Speaking Back to the System: Recommendations for Practice and Policy from the Perspectives of Youth Formerly in Foster Care Who Are LGBTQ. Child Welf. 2020, 97, 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, A. Supporting Youth Aging out of Government Care with Their Transition to College. Ph.D Thesis, Western University, London, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, T.R.; Riley, T.J.; St Jean, N.E.; Ellis, J.D.; Bogard, J.E.; Kisiel, C. Transition Age Youth (TAY) Needs Assessment: Feedback from TAY and Providers Regarding TAY Services, Resources, and Training. Child Welf. 2019, 97, 89–116. [Google Scholar]

- Esaki, N.; Benamati, J.; Yanosy, S.; Middleton, J.S.; Hopson, L.M.; Hummer, V.L.; Bloom, S.L. The Sanctuary Model: Theoretical Framework. Fam. Soc. 2013, 94, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, S.A.; Gauvin, E.; Jamieson, A.; Rathgeber, M.; Faulkner-Gibson, L.; Bell, S.; Davidson, J.; Russel, J.; Burke, S. What Are Effective Strategies for Implementing Trauma-Informed Care in Youth Inpatient Psychiatric and Residential Treatment Settings? A Realist Systematic Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2017, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, A. Trauma-Informed Care Implementation in the Child- and Youth-Serving Sectors: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resil. 2020, 7, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, M.-E.; Matte-Landry, A.; Hivon, M.; Julien, G. La Pédiatrie Sociale En Communauté En Tant Qu’approche Sensible Au Trauma: Une Voie Légitime Vers La Transformation Des Services à l’enfance Au Québec. Trav. Soc. 2023, 69, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D.; King, M.A.; Wissow, L.S. The Central Role of Relationships With Trauma-Informed Integrated Care for Children and Youth. Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, S94–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, E.R.; Yackley, C.R.; Licht, E.S. Developing, Implementing, and Evaluating a Trauma-Informed Care Program within a Youth Residential Treatment Center and Special Needs School. Resid. Treat. Child. Youth 2018, 35, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the Extraction, Analysis, and Presentation of Results in Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, S. L’émergence de l’âge Adulte: De l’impact Des Référentiels Institutionnels En France et Au Québec 1. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/sociologies/3841 (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- de Velde, C.V. Devenir Adulte: Sociologie Comparée de la Jeunesse en Europe, 1re éd.; Lien Social; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bargeman, M.; Smith, S.; Wekerle, C. Trauma-Informed Care as a Rights-Based “Standard of Care”: A Critical Review. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 119 Pt 1, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).