Resolving the Personalisation Agenda in Psychological Therapy Through a Biomedical Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background Information and Definitions

2.1. The Consequences of Failing to Resolve the Personalisation Agenda

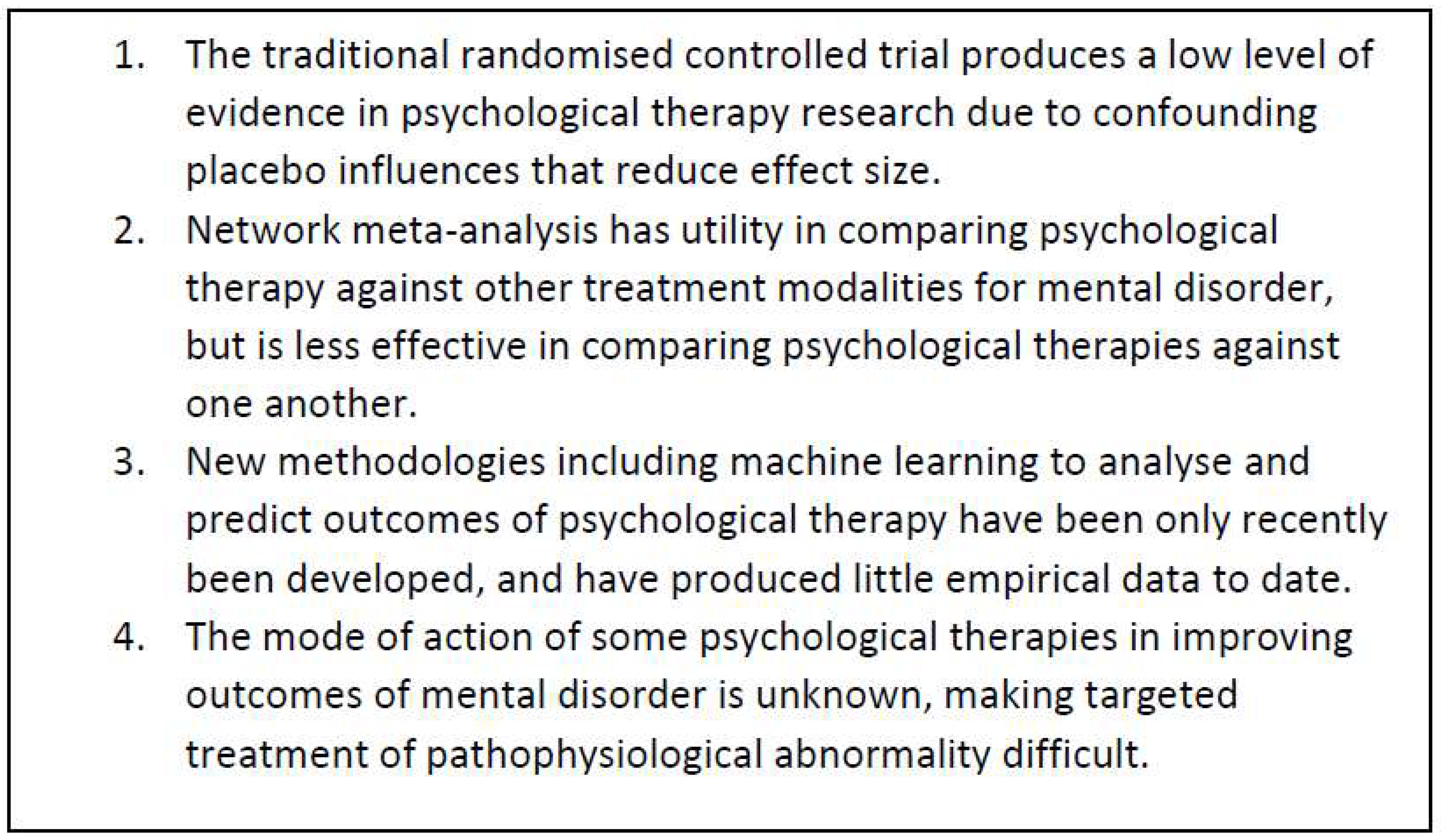

2.2. The Limitations of the Randomised Controlled Trial in Resolving the Personalisation Agenda

2.3. The Limitations of Alternative Research Approaches in Resolving the Personalisation Agenda

- (A).

- New RCT research

- (B).

- Re-analysis of existing data through network meta-analysis

- (C).

- Novel research methodologies including artificial intelligence

- (D).

- Neuroscientific analysis based on neuro-radiological advances

2.4. Applying a Biomedical Model to Resolve the Personalisation Agenda

2.4.1. Basic Principles of the Biomedical Model

- (A).

- Treatment of mental disorder can be based on accurate, standardised diagnosis of both core mental disorders and comorbidities.

- (B).

- Comorbid mental disorders may require contemporaneous or sequential treatment with three levels of intensity psychological treatment modalities: low, medium and high intensity.

- (C).

- (D).

- Most mental disorders respond to placebo plus cognitive behavioural techniques [28]. However, mental disorders associated with trauma only respond partially to this approach and require high-intensity trauma-based therapy for good long-term outcome. The mechanism of action of trauma-based therapies is via neuroplasticity [61].

2.4.2. Applying a Biomedical Model in Clinical Practice

2.4.3. Why a Biomedical Model Can Potentially Resolve the Personalisation Agenda

3. Discussion

3.1. Training Requirements

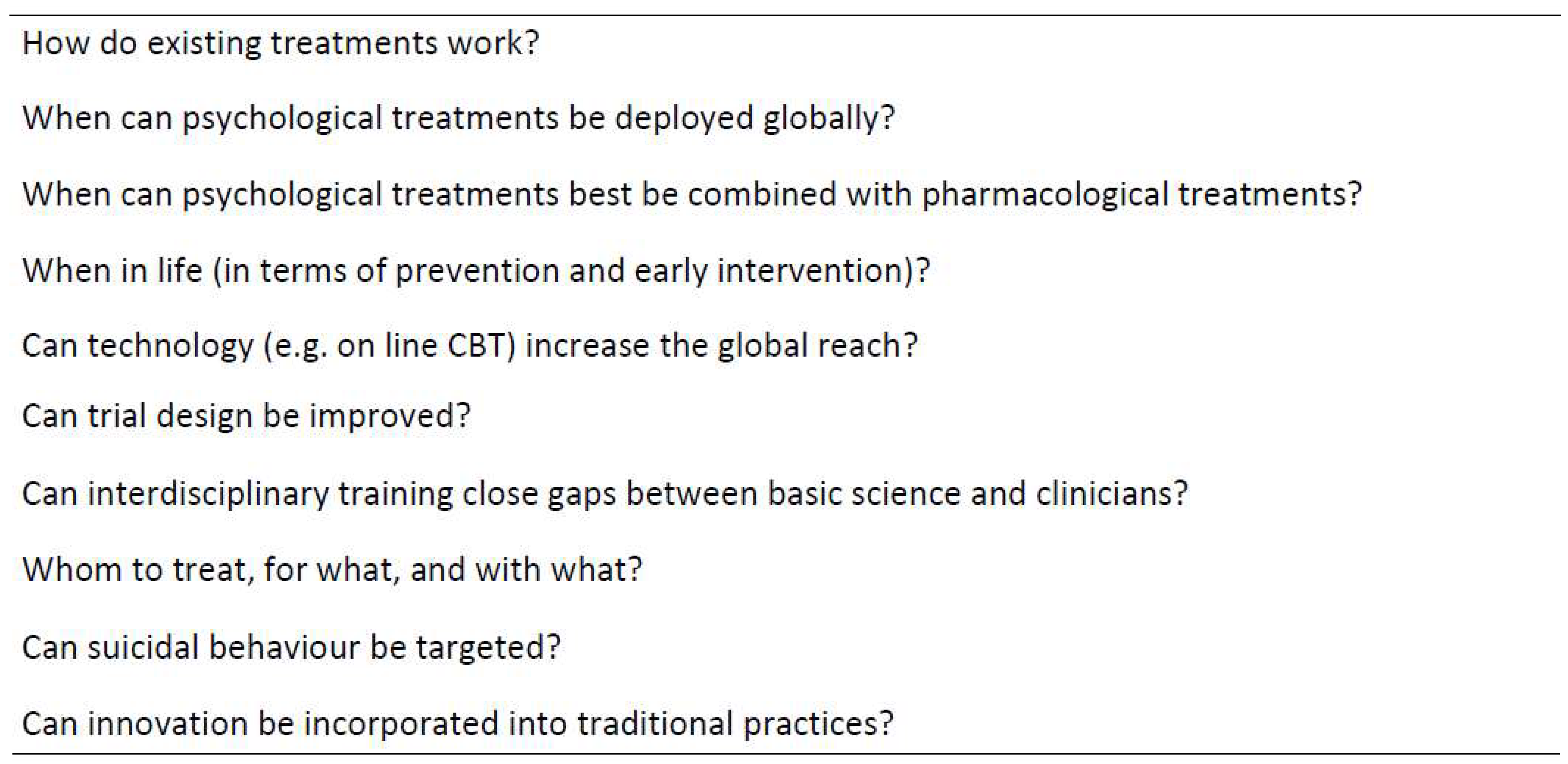

3.2. Further Research

3.3. Limitations

- This article is written from a Western perspective on how mental disorder should be classified and treated, although it does seek to accommodate the World Health Organisation perspective [76] on cross-cultural issues. It makes only passing reference to the role that artificial intelligence and recent advances in psychotherapy research design may play in future in personalising therapy [49].

- Dividing psychological therapies into three levels of intensity may be too simplistic when considering the complexity of the human condition. The article has posited a heuristic model that provides a pragmatic problem-solving approach to an enduring dilemma, but a biomedical approach is only one of the possible approaches [40].

- Much of the data in support of applying a biomedical model for psychological therapy is derived from research into depression. Depression is the most common mental disorder supported by a larger research literature than other mental disorders. Around a third of the references below refer specifically to psychological management of depression, rather than mental disorder more widely. It has been assumed that data can be extrapolated from depression to all mental disorders, based on the generic contribution of dysfunctional and corrective neuroplasticity in mental disorders. This requires analysis by further research using the correct methodologies.

- The biomedical model is based on the hypothesis that trauma-based therapies share their mode of action with other genres of psychological therapy and work via neuroplasticity. Whilst there is some evidence to support this hypothesis [61], the hypothesis has not been confirmed [3] by empirical research.

- There has been no consideration of the ethics of using placebo as a low-intensity treatment for mental disorders. The general public associates placebo with sugar pills, and whilst no subterfuge can be involved in the use of placebo [77], it is not known if telling patients in advance that placebo is being used will dilute its beneficial effects.

4. Conclusions

- 1.

- The personalisation agenda can potentially be resolved by a biomedical approach, which divides psychological therapies into low, medium and high intensity interventions.

- 2.

- Most mental disorders can be treated by generic mental health workers with low- and medium-intensity interventions, which overlap and are based on expectation and cognitive appraisal. High intensity treatments are reserved for mental disorders caused by trauma.

- 3.

- Psychological interventions are complementary not competing, patients with comorbidities may require all three approaches for optimal management and outcome.

- 4.

- The biomedical model posits that it is important to identify psychological trauma when diagnosing mental disorders, as the presence of trauma changes management.

- 5.

- Long-term outcomes of psychological therapy should be evaluated by mixed methods research, given the unique limitations of the RCT in this field.

- 6.

- For the Mental Health Gap programme, where skilled psychological therapy is not available, the combination of low intensity psychological intervention plus exercise may substitute in some mental disorders: EMDR is the most affordable high intensity intervention for trauma.

- 7.

- Resolving the personalisation agenda will not by itself resolve the crisis in psychological therapies: NMA provides evidence that biopsychosocial networks of neuroplasticity-inducing treatments are required to address the relative poverty and comorbidities that drive much mental disorder.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gomez, D.; Taylor, P.; Del Pozo Cruz, B.; van den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M.; et al. Effect of Exercise for Depression: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2024, 384, e075847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdler, S.J.; Confino, J.E.; Woesner, M.E. Exercise as a Treatment for Schizophrenia: A Review. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2019, 49, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, E.A.; Ghaderi, A.; Harmer, C.J.; Ramchandani, P.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Morrison, A.P.; Roiser, J.P.; Bockting, C.L.H.; O'Connor, R.C.; Shafran, R.; et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on Psychological Treatments Research in Tomorrow’s Science. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 237–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Patel, V.; Kieling, C.; Berk, M.; Buchweitz, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.A.; Kessler, R.C.; Kohrt, B.A.; Maj, M.; et al. Time for United Action on Depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 2022, 399, 957–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, R.; Hughes, I. The Dodo Bird Verdict--Controversial, Inevitable and Important: A Commentary on 30 Years of Meta-Analyses. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2009, 16, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnas, S.J.; Knoop, H.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Braamse, A.M.J. Defining and Operationalizing Personalized Psychological Treatment—A Systematic Literature Review. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2024, 53, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.J.; Palk, A.C.; Kendler, K.S. What Is a Mental Disorder? An Exemplar-Focused Approach. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, A.J.; Thase, M.E. Improving Depression Outcome by Patient-Centered Medical Management. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Depression in Adults: Treatment and Management; Nice Guideline [Ng222]; National Institute of Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Addington, D.; Abidi, S.; Garcia-Ortega, I.; Honer, W.G.; Ismail, Z. Canadian Guidelines for the Assessment and Diagnosis of Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, A.W.M.; Colloca, L.; Blease, C.; Annoni, M.; Atlas, L.Y.; Benedetti, F.; Bingel, U.; Büchel, C.; Carvalho, C.; Colagiuri, B.; et al. Implications of Placebo and Nocebo Effects for Clinical Practice: Expert Consensus. Psychother. Psychosom. 2018, 87, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision (Dsm-5-Tr); American Psychiatric Publishing: Washinton, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, P.R. Adult Neuroplasticity: A New “Cure” for Major Depression? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019, 44, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, P.; Melzer, T.; Pavesi, E.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Brocardo, P.S. Exploring the Role of Neuroplasticity in Development, Aging, and Neurodegeneration. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Altered Connectivity in Depression: Gaba and Glutamate Neurotransmitter Deficits and Reversal by Novel Treatments. Neuron 2019, 102, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.A.; Craske, M.G.; Graybiel, A.M. Psychological Treatments: A Call for Mental-Health Science. Nature 2014, 511, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Weitz, E.; Andersson, G.; Hollon, S.D.; van Straten, A. The Effects of Psychotherapies for Major Depression in Adults on Remission, Recovery and Improvement: A Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 159, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazdin, A.E.; Blase, S.L. Rebooting Psychotherapy Research and Practice to Reduce the Burden of Mental Illness. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators GBDS. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Suicide, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Public Health 2025, 10, e189–e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keynejad, R.C.; Spagnolo, J.; Thornicroft, G. Mental Healthcare in Primary and Community-Based Settings: Evidence Beyond the Who Mental Health Gap Action Programme (Mhgap) Intervention Guide. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P. The Dodo Bird and the Need for Scalable Interventions in Global Mental Health-a Commentary on the 25th Anniversary of Wampold et al. (1997). Psychother. Res. 2023, 33, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of 12 Mental Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Bromet, E.J. The Epidemiology of Depression across Cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On. BMJ 2020, 368, m693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckman, J.E.J.; Saunders, R.; Stott, J.; Cohen, Z.D.; Arundell, L.-L.; Eley, T.C.; Hollon, S.D.; Kendrick, T.; Ambler, G.; Watkins, E.; et al. Socioeconomic Indicators of Treatment Prognosis for Adults with Depression a Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of Dsm-Iv Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS DIGITAL. Psychological Therapies, Annual Report on the Use of Iapt Services, 2021-22. NHS DIGITAL. 2022. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/psychological-therapies-annual-reports-on-the-use-of-iapt-services/annual-report-2021-22 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- NHS England. Implementation Guidance 2024-Psychological Therapies for Severe Mental Health Problems; NHS England: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/psychological-therapies-for-people-with-severe-mental-health-problems/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Wampold, B.E. How Important Are the Common Factors in Psychotherapy? An Update. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafra-Tanaka, J.H.; Goicochea-Lugo, S.; Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Taype-Rondan, A. Characteristics and Quality of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Depression in Adults: A Scoping Review. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughren, T.P. The Scientific and Ethical Basis for Placebo-Controlled Trials in Depression and Schizophrenia: An Fda Perspective. Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2001, 16, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Miguel, C.; Harrer, M.; Ciharova, M.; Karyotaki, E. The Overestimation of the Effect Sizes of Psychotherapies for Depression in Waitlist Controlled Trials: A Meta-Analytic Comparison with Usual Care Controlled Trials. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2024, 33, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, J.; Mathers, N. Placebo Stimulates Neuroplasticity in Depression: Implications for Clinical Practice and Research. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1301143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enck, P.; Zipfel, S. Placebo Effects in Psychotherapy: A Framework. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Oud, M.; Karyotaki, E.; Noma, H.; Quero, S.; Cipriani, A.; Arroll, B.; Furukawa, T.A. Psychologic Treatment of Depression Compared with Pharmacotherapy and Combined Treatment in Primary Care: A Network Meta-Analysis. Ann. Fam. Med. 2021, 19, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Iqbal, Z.; Airey, N.D.; Marks, L. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (Iapt) Has Potential but Is Not Sufficient: How Can It Better Meet the Range of Primary Care Mental Health Needs? Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.A.; Beck, A.T. Cognitive Theory and Therapy of Anxiety and Depression: Convergence with Neurobiological Findings. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, J.M.; Richardi, T.M.; Barth, K.S. Dialectical Behavior Therapy as Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder. Ment. Health Clin. 2016, 6, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F. The Role of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (Emdr) Therapy in Medicine: Addressing the Psychological and Physical Symptoms Stemming from Adverse Life Experiences. Perm. J. 2014, 18, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rief, W.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Bryant, R.A.; Clark, D.M.; Ehlers, A.; Holmes, E.A.; McNally, R.J.; Neufeld, C.B.; Wilhelm, S.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; et al. The Future of Psychological Treatments: The Marburg Declaration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 110, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavridis, D.; Giannatsi, M.; Cipriani, A.; Salanti, G. A Primer on Network Meta-Analysis with Emphasis on Mental Health. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2015, 18, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J.; Munder, T.; Gerger, H.; Nüesch, E.; Trelle, S.; Znoj, H.; Jüni, P.; Cuijpers, P. Comparative Efficacy of Seven Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Patients with Depression: A Network Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Miguel, C.; Harrer, M.; Plessen, C.Y.; Ciharova, M.; Ebert, D.; Karyotaki, E. Cognitive Behavior Therapy Vs. Control Conditions, Other Psychotherapies, Pharmacotherapies and Combined Treatment for Depression: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Including 409 Trials with 52,702 Patients. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Noma, H.; Karyotaki, E.; Vinkers, C.H.; Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A. A Network Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Psychotherapies, Pharmacotherapies and Their Combination in the Treatment of Adult Depression. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavranezouli, I.; Megnin-Viggars, O.; Pedder, H.; Welton, N.J.; Dias, S.; Watkins, E.; Nixon, N.; Daly, C.H.; Keeney, E.; Eadon, H.; et al. A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Psychological, Psychosocial, Pharmacological, Physical and Combined Treatments for Adults with a New Episode of Depression. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 75, 102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, E.R.; Newbold, A. Factorial Designs Help to Understand How Psychological Therapy Works. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Research Design in Clinical Psychology, 5th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chekroud, A.M.; Bondar, J.; Delgadillo, J.; Doherty, G.; Wasil, A.; Fokkema, M.; Cohen, Z.; Belgrave, D.; DeRubeis, R.; Iniesta, R.; et al. The Promise of Machine Learning in Predicting Treatment Outcomes in Psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, J.; Gonzalez Salas Duhne, P. Targeted Prescription of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Versus Person-Centered Counseling for Depression Using a Machine Learning Approach. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkraut, J.J. The Catecholamine Hypothesis of Affective Disorders: A Review of Supporting Evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 1965, 122, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncrieff, J.; Cooper, R.E.; Stockmann, T.; Amendola, S.; Hengartner, M.P.; Horowitz, M.A. The Serotonin Theory of Depression: A Systematic Umbrella Review of the Evidence. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3243–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.B.; Duman, R. Neuroplasticity in Cognitive and Psychological Mechanisms of Depression: An Integrative Model. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Xu, H.; Yu, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, C. Neural Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Activation Likelihood Estimation Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 853804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howick, J. The Power of Placebos. How the Science of Placebos and Nocebos Can Improve Healthcare; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Howick, J.; Moscrop, A.; Mebius, A.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Lewith, G.; Bishop, F.L.; Mistiaen, P.; Roberts, N.W.; Dieninytė, E.; Hu, X.Y.; et al. Effects of Empathic and Positive Communication in Healthcare Consultations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. R. Soc. Med. 2018, 111, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashar, Y.K.; Chang, L.J.; Wager, T.D. Brain Mechanisms of the Placebo Effect: An Affective Appraisal Account. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colloca, L.; Miller, F.G. How Placebo Responses Are Formed: A Learning Perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 1859–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, S.G. The Persistent Power of Placebo. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.M.; Chin Fatt, C.R.; Jha, M.; Fonzo, G.A.; Grannemann, B.D.; Carmody, T.; Ali, A.; Aslan, S.; Almeida, J.R.C.; Deckersbach, T.; et al. Cerebral Blood Perfusion Predicts Response to Sertraline Versus Placebo for Major Depressive Disorder in the Embarc Trial. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 10, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M.; Shirotsuki, K.; Sugaya, N. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Management of Mental Health and Stress-Related Disorders: Recent Advances in Techniques and Technologies. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2021, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collerton, D. Psychotherapy and Brain Plasticity. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelofs, K.; Spinhoven, P. Trauma and Medically Unexplained Symptoms Towards an Integration of Cognitive and Neuro-Biological Accounts. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol, A.L.; Sieberg, C.B.; Clauw, D.J.; Hassett, A.L.; Moser, S.E.; Brummett, C.M. The Association between a History of Lifetime Traumatic Events and Pain Severity, Physical Function, and Affective Distress in Patients with Chronic Pain. J. Pain. 2016, 17, 1334–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rief, W.; Barsky, A.J.; Bingel, U.; Doering, B.K.; Schwarting, R.; Wöhr, M.; Schweiger, U. Rethinking Psychopharmacotherapy: The Role of Treatment Context and Brain Plasticity in Antidepressant and Antipsychotic Interventions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 60, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Fernandes, M.S.; Ordonio, T.F.; Santos, G.C.J.; Santos, L.E.R.; Calazans, C.T.; Gomes, D.A.; Santos, T.M. Effects of Physical Exercise on Neuroplasticity and Brain Function: A Systematic Review in Human and Animal Studies. Neural Plast. 2020, 2020, 8856621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulzen, M.; Veselinovic, T.; Grunder, G. Effects of Psychotropic Drugs on Brain Plasticity in Humans. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2014, 32, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.T.; Holtzheimer, P.E.; Gao, S.; Kirwin, D.S.; Price, R.B. Leveraging Neuroplasticity to Enhance Adaptive Learning: The Potential for Synergistic Somatic-Behavioral Treatment Combinations to Improve Clinical Outcomes in Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 85, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared Decision Making: A Model for Clinical Practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, S.; Suzuki, M.; McCabe, R. An Ideal-Type Analysis of People’s Perspectives on Care Plans Received from the Emergency Department Following a Self-Harm or Suicidal Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, B.J. The Biomedical Model of Mental Disorder: A Critical Analysis of Its Validity, Utility, and Effects on Psychotherapy Research. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheff, T.J. The Labelling Theory of Mental Illness. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermeyer, M.C.; Matschinger, H. The Stigma of Mental Illness: Effects of Labelling on Public Attitudes Towards People with Mental Disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2003, 108, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, P. The Shifting Engines of Medicalization. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wong, K.K.; Lei, O.K.; Nie, J.; Shi, Q.; Zou, L.; Kong, Z. Comparative Effectiveness of Multiple Exercise Interventions in the Treatment of Mental Health Disorders: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A New Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Update of Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keynejad, R.C.; Dua, T.; Barbui, C.; Thornicroft, G. Who Mental Health Gap Action Programme (Mhgap) Intervention Guide: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Low and Middle-Income Countries. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptchuk, T.J.; Miller, F.G. Placebo Effects in Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seymour, J. Resolving the Personalisation Agenda in Psychological Therapy Through a Biomedical Approach. BioMed 2025, 5, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5030019

Seymour J. Resolving the Personalisation Agenda in Psychological Therapy Through a Biomedical Approach. BioMed. 2025; 5(3):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5030019

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeymour, Jeremy. 2025. "Resolving the Personalisation Agenda in Psychological Therapy Through a Biomedical Approach" BioMed 5, no. 3: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5030019

APA StyleSeymour, J. (2025). Resolving the Personalisation Agenda in Psychological Therapy Through a Biomedical Approach. BioMed, 5(3), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomed5030019