Indications for Dialysis in Lithium Toxicity: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

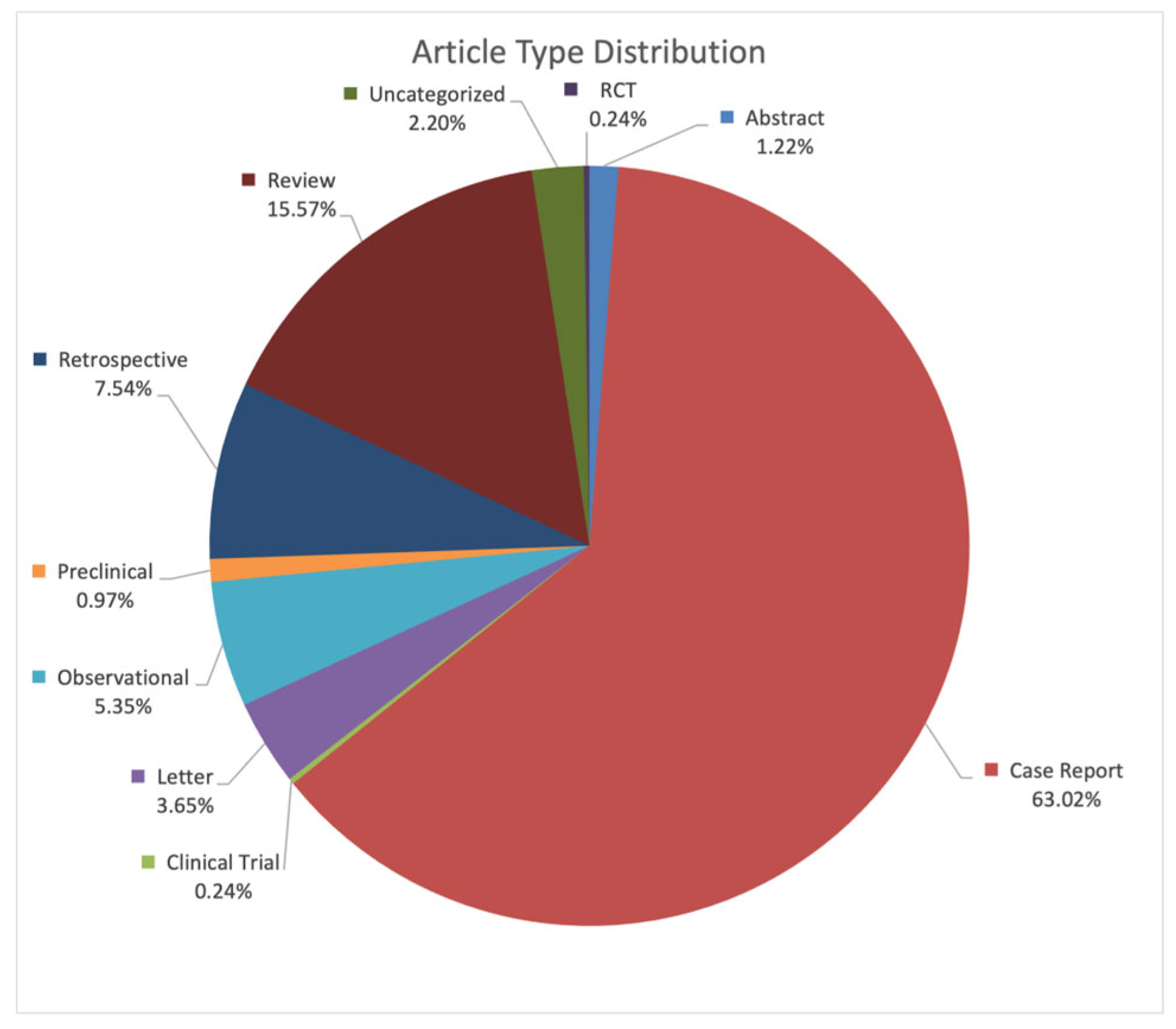

2. Methods

3. Discussion

3.1. Pathophysiology of Lithium Toxicity

3.2. Identification of Lithium Toxicity

3.3. Dialysis for Lithium Toxicity

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fiorillo, A.; Sampogna, G.; Albert, U.; Maina, G.; Perugi, G.; Pompili, M.; Rosso, G.; Sani, G.; Tortorella, A. Facts and myths about the use of lithium for bipolar disorder in routine clinical practice: An expert consensus paper. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B. Bipolar disorder: The foundational role of mood stabilizers. Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, T.G.; Olfson, M.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Wilkinson, S.T. 20-Year Trends in the Pharmacologic Treatment of Bipolar Disorder by Psychiatrists in Outpatient Care Settings. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahwa, M.; Elsayed, O.H.; El-Mallakh, R.S. The paradox of vanishing lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2023, 25, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Mantingh, T.; de Mendiola, X.P.; Samalin, L.; Undurraga, J.; Strejilevich, S.; Severus, E.; Bauer, M.; González-Pinto, A.; Nolen, W.A.; et al. Clinicians’ preferences and attitudes towards the use of lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders around the world: A survey from the ISBD Lithium task force. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2023, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeroff, C.B.; Evans, D.L.; Gyulai, L.; Sachs, G.S.; Bowden, C.L.; Gergel, I.P.; Oakes, R.; Pitts, C.D. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine and paroxetine in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolen, W.A.; Licht, R.W.; Young, A.H.; Malhi, G.S.; Tohen, M.; Vieta, E.; Kupka, R.W.; Zarate, C.; Nielsen, R.E.; Baldessarini, R.J.; et al. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019, 21, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, C.T.; Newmark, R.L.; Wisner, K.L.; Stika, C.; Avram, M.J. Lithium Pharmacokinetics in the Perinatal Patient with Bipolar Disorder. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedya, S.A.; Avula, A.; Swoboda, H.D. Lithium Toxicity. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Boltan, D.D.; Fenves, A.Z. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2008, 21, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallakh, R.S. Acute lithium neurotoxicity. Psychiatr. Dev. 1986, 4, 311–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, F.J. Lithium toxicity: The importance of clinical signs. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2010, 71, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowry, J.B.; Spyker, D.A.; Cantilena, L.R., Jr.; Bailey, J.E.; Ford, M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 949–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spatola, L.; Maringhini, S.; Canale, C.; Granata, A.; D’AMico, M. Lithium poisoning and renal replacement therapy: Pathophysiology and current clinical recommendations. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 55, 2501–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjeani, E.M.; Aubry, J.-M. Lithium: Updated human knowledge using an evidence-based approach: Part I: Clinical efficacy in bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs 2009, 23, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, M. Lithium side effects and toxicity: Prevalence and management strategies. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Balkhi, S.; Megarbane, B.; Poupon, J.; Baud, F.J.; Galliot-Guilley, M. Lithium poisoning: Is determination of the red blood cell lithium concentration useful? Clin. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallakh, R.S. Lithium and ECT Interaction. Convuls. Ther. 1987, 3, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Netto, I.; Phutane, V.H.; Ravindran, B. Lithium neurotoxicity due to second-generation antipsychotics combined with lithium: A systematic review. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2019, 21, 27431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenves, A.Z.; Emmett, M.; White, M.G. Lithium intoxication associated with acute renal failure. South. Med. J. 1984, 77, 1472–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.; Stegmayr, B.; Renberg, E.S.; Werneke, U. Lithium intoxication: Incidence, clinical course and renal function—A population-based retrospective cohort study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabibzadeh, N.; Faucon, A.-L.; Vidal-Petiot, E.; Serrano, F.; Males, L.; Fernandez, P.; Khalil, A.; Rouzet, F.; Tardivon, C.; Mazer, N.; et al. Determinants of Kidney Function and Accuracy of Kidney Microcysts Detection in Patients Treated with Lithium Salts for Bipolar Disorder. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 784298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabibzadeh, N.; Vidal-Petiot, E.; Cheddani, L.; Haymann, J.-P.; Lefevre, G.; Etain, B.; Bellivier, F.; Marlinge, E.; Delavest, M.; Vrtovsnik, F.; et al. Chronic Lithium Therapy and Urine-Concentrating Ability in Individuals with Bipolar Disorder: Association Between Daily Dose and Resistance to Vasopressin and Polyuria. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022, 7, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederlof, M.; Heerdink, E.R.; Egberts, A.C.G.; Wilting, I.; Stoker, L.J.; Hoekstra, R.; Kupka, R.W. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: An international survey. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2018, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLeod-Glover, N.; Chuang, R. Chronic lithium toxicity Considerations and systems analysis. Can. Fam. Physician 2020, 66, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Almadani, A.H.; AlBuqami, F.H.; A Aljaffer, M. Challenges in the Clinical Diagnosis of Lithium Toxicity: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e47503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurnberger, J.I., Jr. Diuretic-induced lithium toxicity presenting as mania. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1985, 173, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Kantesaria, A.N.; Chaikovsky, L.I. Lithium toxicity presenting as mania. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1987, 21, 979–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.E.; Chng, W.Q.; Teo, D.B. Looking Beyond Numbers: Lithium Toxicity Within Therapeutic Levels. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, e155–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancin, S.; Palomares, S.M.; Sguanci, M.; Palmisano, A.; Gazineo, D.; Parozzi, M.; Ricco, M.; Savini, S.; Ferrara, G.; Anastasi, G.; et al. Relational skills of nephrology and dialysis nurses in clinical care settings: A scoping review and stakeholder consultation. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2025, 82, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle, K.M.P.; Magro, M.M.; Tocora, D.G.; Boldoba, N.B.; Puncel, C.B.; Obregón, A.S.; Palomares, J.R.R.; Fuente, G.D.A.D.L. Medium cut-off membrane expanded hemodialysis for Lithium removal: A case report. Front. Toxicol. 2025, 7, 1677299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagappan, R.; Parkin, W.G.; Holdsworth, S.R. Acute lithium intoxication. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2002, 30, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.F.; Schreiner, G.E. Hazards and complications of dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1965, 273, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pockros, B.M.; Finch, D.J.; Weiner, D.E. Dialysis and Total Health Care Costs in the United States and Worldwide: The Financial Impact of a Single-Payer Dominant System in the US. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 2137–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavonas, E.J.; Buchanan, J. Hemodialysis for lithium poisoning. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-H.; Tsai, K.-F.; Hsu, P.-C.; Hsieh, M.-H.; Fu, J.-F.; Wang, I.-K.; Liu, S.-H.; Weng, C.-H.; Huang, W.-H.; Hsu, C.-W.; et al. Hemodialysis Treatment for Patients with Lithium Poisoning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoroski, R.A.; Lindquist, D.M.; Pearce, J.M. Lithium compartmentation in brain by 7Li MRS: Effect of total lithium concentration. NMR Biomed. 2013, 26, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallakh, R. Preventing bipolar relapse while avoiding lithium toxicity: The role of the lithium ratio and intraerythrocyte lithium concentration determination. Lithium 1994, 5, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mallakh, R.S. Ion homeostasis and the mechanism of action of lithium. Clin. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 4, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallakh, R.S.; Huff, M.O. Mood stabilizers and ion regulation. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2001, 9, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meertens, J.H.; Jagernath, D.R.; Eleveld, D.J.; Zijlstra, J.G.; Franssen, C.F. Haemodialysis followed by continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration in lithium intoxication; a model and a case. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 20, e70–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, B.S.; Goldfarb, D.S.; Dargan, P.I.; Friesen, M.; Gosselin, S.; Hoffman, R.S.; Lavergne, V.; Nolin, T.D.; Ghannoum, M. Extracorporeal Treatment for Lithium Poisoning: Systematic Review and Recommendations from the EXTRIP Workgroup. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallakh, R.S. Treatment of acute lithium toxicity. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 1984, 26, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tondo, L.; Alda, M.; Bauer, M.; Bergink, V.; Grof, P.; Hajek, T.; Lewitka, U.; Licht, R.W.; Manchia, M.; Müller-Oerlinghausen, B.; et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: Guide for users and prescribers. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2019, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylianskii, J.; Austin, E.; Gold, W.L.; Wu, P.E. A 54-year-old woman with chronic lithium toxicity. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2021, 193, E1345–E1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird-Gunning, J.; Lea-Henry, T.; Hoegberg, L.C.G.; Gosselin, S.; Roberts, D.M. Lithium Poisoning. J. Intensive Care Med. 2017, 32, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Santos, S.; Ferreira, S.G.; Fernandes, L.; Almeida, P. Chronic Lithium Intoxication: A Challenging Diagnosis. Cureus 2024, 16, e52626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, S.; Illg, Z.N.; Moran, T.P.; Morgan, B.W.; Carpenter, J.E. Predictors of prolonged supratherapeutic serum lithium concentrations: A retrospective chart review. Clin. Toxicol. 2024, 62, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahli, G.S.; Bell, E.; Outhred, T.; Berk, M. Lithium therapy and its interactions. Aust. Prescr. 2020, 43, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, K.R.; Thampy, A. The syndrome of irreversible lithium-effectuated neurotoxicity. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2005, 28, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.F.; Gomes, R. Syndrome of irreversible lithium-effectuated neurotoxicity (SILENT): A review. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, S717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdoux, H.; Debruyne, A.-L.; Queuille, E.; De Leon, J. A reappraisal of the role of fever in the occurrence of neurological sequelae following lithium intoxication: A systematic review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmol, S.; Beltre, N.; Margolesky, J. Syndrome of irreversible lithium-effectuated neurotoxicity (SILENT): A preventable cerebellar disorder. Cerebellum 2024, 23, 1733–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adityanjee. The syndrome of irreversible lithium effectuated neurotoxicity. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1987, 50, 1246–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, I.M.; Cuningham, J. Persisting neurologic sequelae of lithium carbonate therapy. Arch. Neurol. 1983, 40, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdoux, H.; Bourgeois, M.L. Irreversible neurologic sequelae caused by lithium. L’encephale 1991, 17, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Stip, E.; Black, D.N.; Lew, V.; Langlois, R. Neurologic sequelae secondary to acute lithium poisoning. Can. J. Psychiatry 1999, 44, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczny, K.; Detraux, J.; Bouckaert, F. The Syndrome of Irreversible Lithium-Effectuated Neurotoxicity: A Scoping Review. Anatol. J. Psychiatry 2024, 25, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünfeld, J.-P.; Rossier, B.C. Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2009, 5, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, N.A.; Cheng, S.; Isoardi, K.; Chiew, A.L.; Siu, W.; Vecellio, E.; Chan, B.S. Haemodialysis for lithium poisoning: Translating EXTRIP recommendations into practical guidelines. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajemian, R.; Bullock, D.; Grossberg, S. A model of movement coordinates in the motor cortex: Posture-dependent changes in the gain and direction of single cell tuning curves. Cereb. Cortex 2001, 11, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barter, J.W.; Li, S.; Sukharnikova, T.; Rossi, M.A.; Bartholomew, R.A.; Yin, H.H. Basal ganglia outputs map instantaneous position coordinates during behavior. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 2703–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, H.; Berg, R.W. Why Firing Rate Distributions Are Important for Understanding Spinal Central Pattern Generators. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 719388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, N. Common Toxidromes and the Role of Extracorporeal Detoxification. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020, 27, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelfarb, J.; Vanholder, R.; Mehrotra, R.; Tonelli, M. The current and future landscape of dialysis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Yell, N.; Herbert, L.; Browne, T.; Hung, P. Availability and Quality of Dialysis Care in Rural versus Urban US Counties. Am. J. Nephrol. 2024, 55, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, V.; Otani, T.; Freirias, A.; Calfat, E.; Aoki, P.; Cross, S.; Sumskis, S.; Kanaan, R.; Cordeiro, Q.; Uchida, R. Predictors of Disagreement Between Diagnoses from Consult Requesters and Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019, 207, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovar, D.; El Balkhi, S.; Curis, E.; Deye, N.; Mégarbane, B. Lithium poisoning in the intensive care unit: Predictive factors of severity and indications for extracorporeal toxin removal to improve outcome. Clin. Toxicol. 2016, 54, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, F.; Wilms, H.; Schultze, G.; Offerman, G.; Molzahn, M. Effect of plasma protein binding, volume of distribution and molecular weight on the fraction of drugs eliminated by hemodialysis. Clin. Nephrol. 1983, 19, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Okusa, M.D.; Crystal, L.J.T. Clinical manifestations and management of acute lithium intoxication. Am. J. Med. 1994, 97, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bommel, E.F.; Kalmeijer, M.D.; Ponssen, H.H. Treatment of life-threatening lithium toxicity with high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Am. J. Nephrol. 2000, 20, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet, G.; Bouchard, J.; Ghannoum, M.; Decker, B.S. Available extracorporeal treatments for poisoning: Overview and limitations. Semin. Dial. 2014, 27, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaccadori, E.; Maggiore, U.; Parenti, E.; Greco, P.; Cabassi, A. Sustained low-efficiency dialysis (SLED) for acute lithium intoxication. NDT Plus 2008, 1, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.E.; Amdisen, A. Lithium intoxication: Report of 23 cases and review of 100 cases from the literature. QJM Int. J. Med. 1978, 47, 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Deville, K.; Charlton, N.; Askenazi, D. Use of extracorporeal therapies to treat life-threatening intoxications. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iman, Y.; Bamforth, R.; Ewhrudjakpor, R.; Komenda, P.; Gorbe, K.; Whitlock, R.; Bohm, C.; Tangri, N.; Collister, D. The impact of dialysate flow rate on haemodialysis adequacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, D.; Basit, H.; Knohl, S. Physiology, Glomerular Filtration Rate. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Plenge, P.; Stensgaard, A.; Jensen, H.V.; Thomsen, C.; Mellerup, E.T.; Henriksen, O. 24-hour lithium concentration in human brain studied by Li-7 magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biol. Psychiatry 1994, 36, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, A.; Sauder, P.; Kopferschmitt, J.; Jaegle, M.L. Toxicokinetics of lithium intoxication treated by hemodialysis. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1985, 23, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Grade | Clinical Presentation | Serum Lithium Level | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Nausea, vomiting, tremor, mild dyscoordination, hyperreflexia, lethargy, fatigue, weakness, fasciculations, muscle rigidity, ataxia, apathy, mania | <1.5 mEq/L | Fluids, support, rarely dialysis |

| Moderate | More severe dyscoordination (ataxia, dysarthria, blurry vision, etc.), more severe fasciculations, myoclonus, nystagmus, muscle weakness, dyskinesias, confusion, delirium | 1.5–2.5 mEq/L | Usually dialysis, but may do well with fluids and support |

| Severe | Seizures, confusion, delirium, coma, death | >2.5 mEq/L | Always dialysis |

| 1- Any moderate toxicity ([Li+] = 1.5–2.5 mEq/L) if toxicity developed slowly/chronically |

| 2- If lithium level > 2.5 mEq/L with evidence of moderate toxicity (i.e., neurologic symptoms other than dyscoordination |

| 3- If lithium level > 4.0 mEq/L |

| 4- If confusion is present (Glasgow Coma Score ≤ 10) |

| 5- In the presence of a decreased level of consciousness, seizures, or life-threatening dysrhythmias irrespective of [Li+] |

| 6- If the expected time to obtain a [Li+] < 1.0 mEq/L with optimal management is >36 h |

| 1. Initial Assessment | • Determine exposure type: Acute/Chronic/Acute-on-Chronic • Assess mental status, ataxia, dyscoordination, renal function • Labs: serum Li+, electrolytes, creatinine |

| 2. Stabilization | • Stop lithium immediately • Start IV saline for all patients • Treat fever, dehydration, infections |

| 3. Dialysis Decision | Dialyze if: • ↓ Consciousness, seizures, severe neurologic signs • Li+ > 4.0 mEq/L, or >1.5 mEq/L in chronic toxicity • Renal failure or slow improvement If HD unavailable: CRRT or SLED; continue hydration |

| 4. During and After Dialysis | • Check Li+ every 2–4 h • Repeat dialysis if rebound occurs • Continue until Li+ < 1.0 mEq/L and falling |

| 5. Multidisciplinary Approach | • Early involvement of Nephrology, Toxicology, Psychiatry, ICU • Crucial in chronic or neurologically severe cases |

| 6. Prevention and Follow-Up | • Monitor during illness, dehydration, medication changes • Avoid antipsychotics that increase neurotoxicity risk • Symptoms > 2 months → evaluate for SILENT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hacisalihoglu Aydin, I.; Ibrahim, K.; Abuelazm, H.; Stephenson, T.L.; Brikker, E.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Indications for Dialysis in Lithium Toxicity: A Narrative Review. Kidney Dial. 2026, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial6010005

Hacisalihoglu Aydin I, Ibrahim K, Abuelazm H, Stephenson TL, Brikker E, El-Mallakh RS. Indications for Dialysis in Lithium Toxicity: A Narrative Review. Kidney and Dialysis. 2026; 6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial6010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleHacisalihoglu Aydin, Irem, Kirolos Ibrahim, Hagar Abuelazm, Tyler L. Stephenson, Eugenia Brikker, and Rif S. El-Mallakh. 2026. "Indications for Dialysis in Lithium Toxicity: A Narrative Review" Kidney and Dialysis 6, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial6010005

APA StyleHacisalihoglu Aydin, I., Ibrahim, K., Abuelazm, H., Stephenson, T. L., Brikker, E., & El-Mallakh, R. S. (2026). Indications for Dialysis in Lithium Toxicity: A Narrative Review. Kidney and Dialysis, 6(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial6010005