Oral Frailty and Its Association with Cognitive Function and Muscle Strength in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Retrospective Observational Study

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Comprehensive Geriatric and Motor Assessment

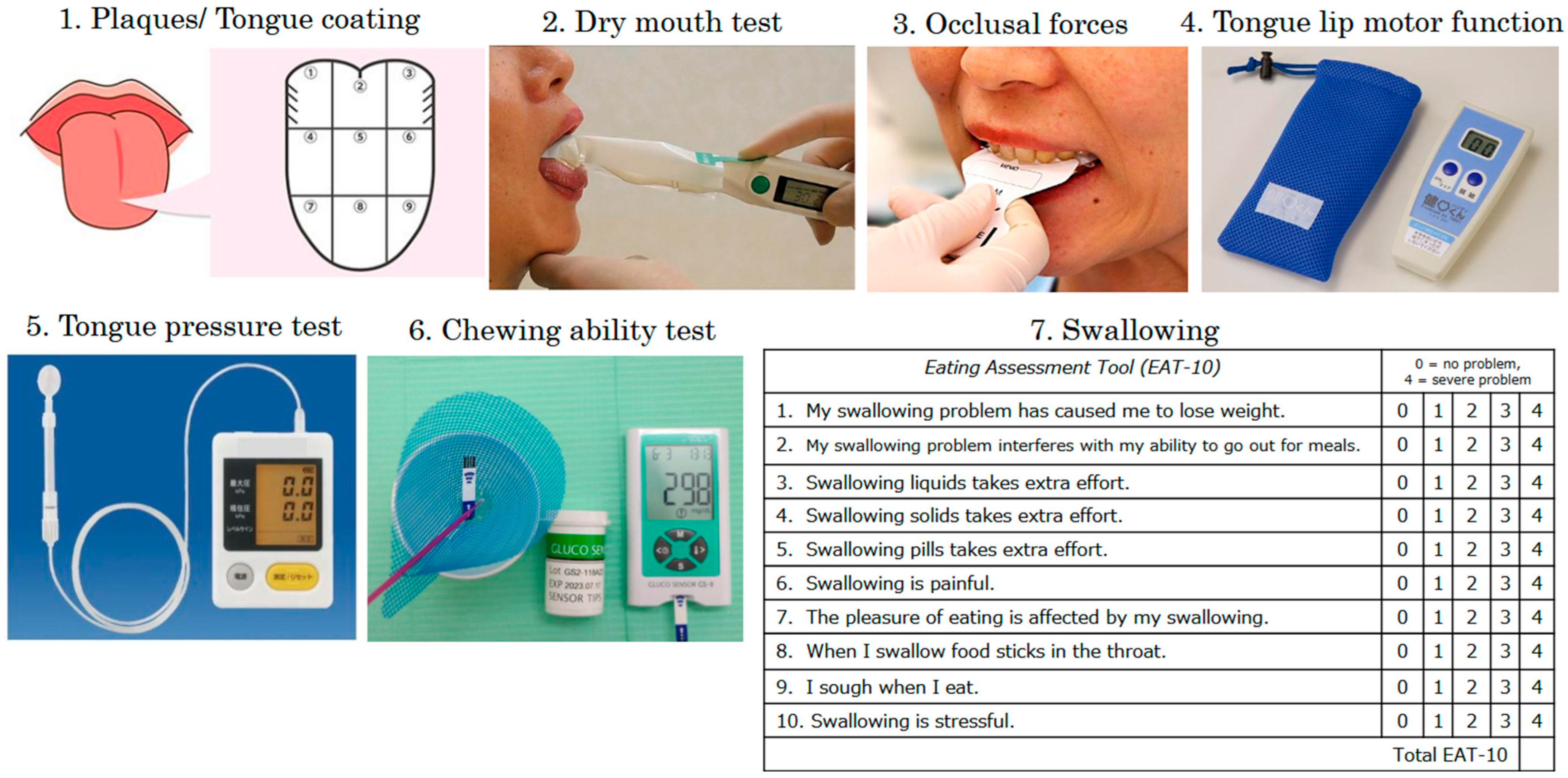

2.3. Oral Cavity Function Assessment

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Oral Hypofunction

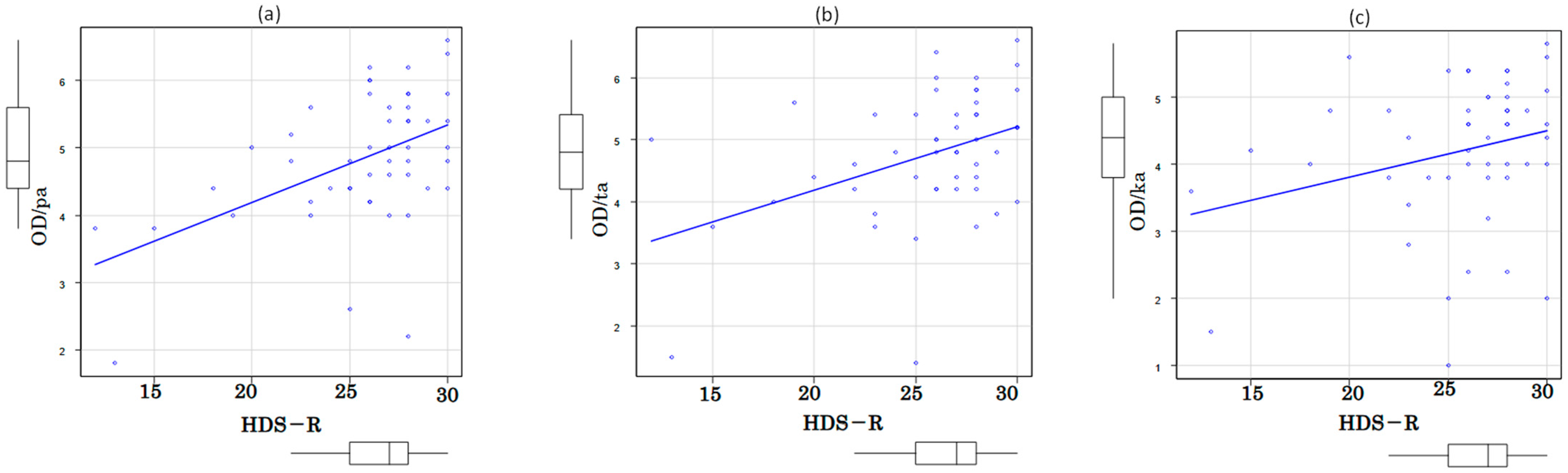

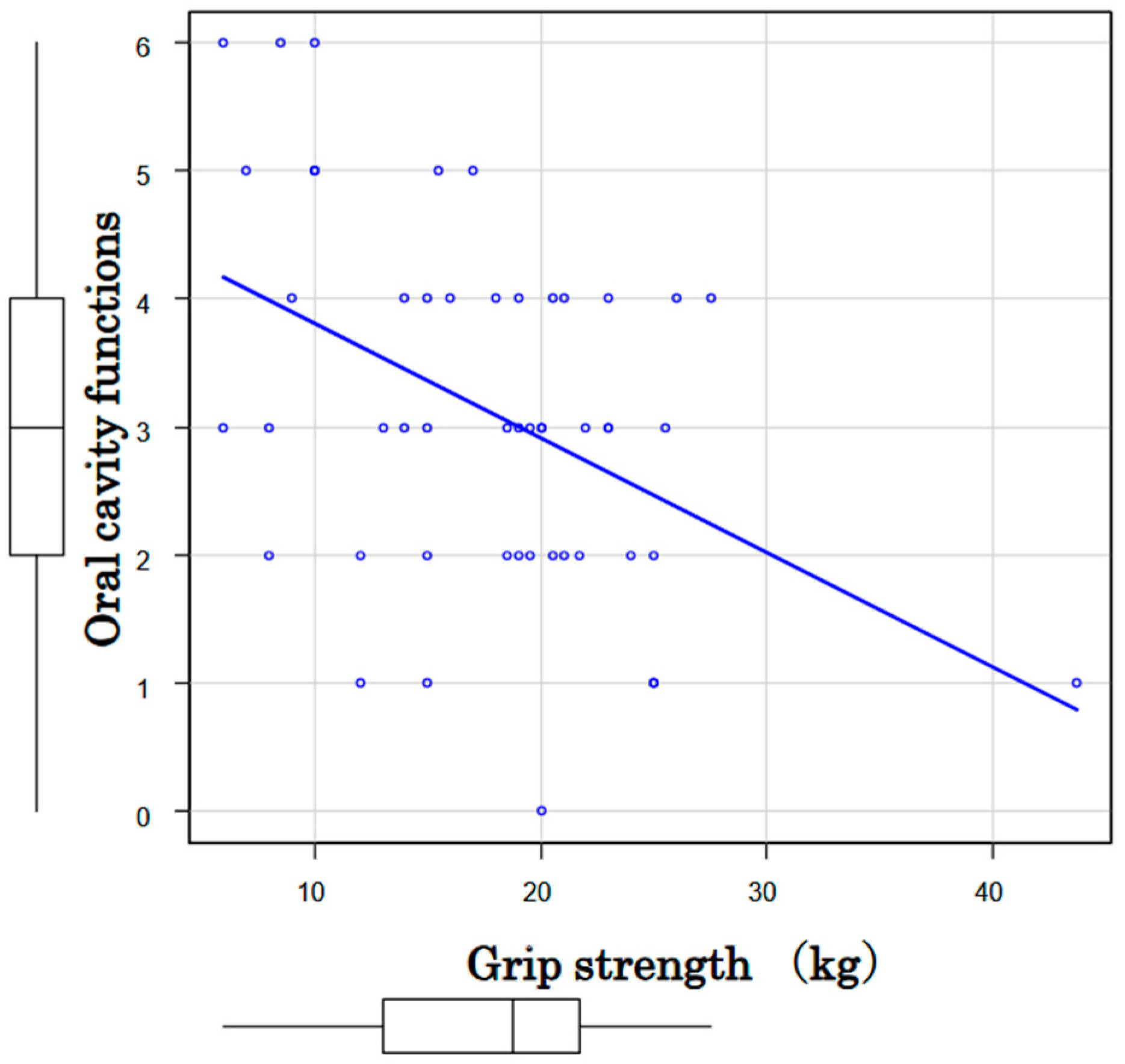

3.2. Associations among Oral Function, Cognition and Motor Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MHD | maintenance hemodialysis |

| DEXA | dual energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| CT | computed tomography |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| UCG | ultrasound cardiography |

| IADLs | instrumental activities of daily living |

| CGA | comprehensive geriatric assessment |

| TMIG index | Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology index |

| GDS | Geriatric Depression Scale |

| HDS-R | Hasegawa’s Dementia Scale-Revised |

| SPPB | short physical performance battery |

| TCI | Tongue Coating Index |

| OD | oral diadochokinesis |

| OFI | oral frailty index |

References

- Dibello, V.; Zupo, R.; Sardone, R.; Lozupone, M.; Castellana, F.; Dibello, A.; Daniele, A.; De Pergola, G.; Bortone, I.; Lampignano, L.; et al. Oral frailty and its determinants in older age: A systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e507–e520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Okada, K.; Kondo, M.; Matsushita, T.; Nakazawa, S.; Yamazaki, Y. Oral Health for achieving longevity. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E. Editorial: Oral frailty. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakuchi, S.; Tsuga, K.; Ikebe, K.; Ueda, T.; Tamura, F.; Nagao, K.; Furuya, J.; Matsuo, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Kanazawa, M.; et al. Oral hypofunction in the older population: Position paper of the Japanese Society of Gerodontology in 2016. Gerodontology 2018, 35, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagatani, M.; Iijima, K. Oral frailty prevention to achieve healthy longevity in aging society. J. Jpn. Soc. Dial. Ther. 2021, 36, 254–263. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Masaki, T.; Hanabusa, N.; Abe, M.; Joki, N.; Hoshino, J.; Taniguchi, M.; Kikuchi, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Goto, S.; Komaba, H.; et al. 2023 Annual dialysis data report, JSDT renal data registry. J. Jpn. Soc. Dial. Ther. 2024, 57, 543–620. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Toba, K. The guideline for comprehensive geriatric assessment. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi Jpn. J. Geriatr. 2005, 42, 177–180. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, M.; Huang, D. Oral frailty: A concept analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, A.; Mizutani, S.; Oku, S.; Yatsugi, H.; Chu, T.; Liu, X.; Iyota, K.; Kishimoto, H.; Kashiwazaki, H. Association between oral function and physical pre-frailty in community-dwelling older people: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Shen, Y.; Leng, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y. The prevalence of oral frailty among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2024, 15, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, Y.; Motokawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Shirobe, M.; Inagaki, H.; Motohashi, Y.; Edahiro, A.; Hirano, H.; Kitamura, A.; Awata, S.; et al. Association of eating alone with oral frailty among community-dwelling older adults in Japan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 87, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Hirano, H.; Kikutani, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohara, Y.; Furuya, H.; Tetsuo, T.; Akishita, M.; Iijima, K. Oral frailty as a risk factor for physical frailty and mortality in community-dwelling elderly. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Hirano, H.; Ohara, Y.; Nishimoto, M.; Iijima, K. Oral Frailty Index-8 in the risk assessment of new-onset oral frailty and functional disability among community-dwelling older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 94, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanditha, K.M.; Raghavendra, S.K.N.; Thippeswamy, H.M.; Giridhar, K.; Devananda, D. Prevalence of xerostomia in patients on haemodialysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerodontology 2021, 38, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, H.; Kariyasu, M.; Sumi, Y.; Yamasaki, K. Labial closure force, activities of daily living, and cognitive function in frail elderly persons. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi Jpn. J. Geriatr. 2008, 45, 520–525. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasato, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ichijo, K.; Yamaguchi, R.; Takashima, H.; Maruyama, T.; Abe, M. Oral frailty as a risk factor for malnutrition and sarcopenia in patients on hemodialysis: A prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonenaga, K. Oral frailty and interprofessional cooperation. J. Jpn. Dent. Assoc. 2024, 77, 35–45. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Emmert-Streib, F.; Tripathi, S.; Matos Simoes, R.; Hawwa, F.; Dehmer, M. The human disease network. Syst. Biomed. 2013, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, X. An analysis of influencing factors of oral frailty in the elderly in the community. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 50 | 35 | 15 |

| Age (yr); median (range) | 77.5 (37–90) | 77 (37–90) | 79 (49–90) |

| History of hemodialysis (months); median (range) | 94.5 (5–266) | 87 (7–246) | 122 (5–266) |

| Basic disease | |||

| Diabetic kidney disease | 28 | 21 | 7 |

| Nephrosclerosis | 13 | 10 | 3 |

| Nephritis | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Others | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| TMIG Index of Competence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Instrumental | Intellectual | Social | ||

| Full | 15% | 35% | 42% | 19% | |

| Decreased | 85% | 65% | 58% | 81% | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale 15 | Vitality Index | HDS-R | |||

| 10≤: depression | 15% | Full | 77% | 20≥: cognitive decline | 19% |

| 10> | 85% | Decreased | 23% | 20< | 81% |

| Number | Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral frailty | 33 | 66% | |

| 1 | Plaques/tongue coating | 35 | 70% |

| 2 | Dry mouth test | 7 | 14% |

| 3 | Occlusal forces | 24 | 48% |

| 4 | Tongue-lip motor function | 50 | 100% |

| pa | 44 | 88% | |

| ta | 45 | 90% | |

| ka | 50 | 100% | |

| 5 | Tongue pressure test | 25 | 50% |

| 6 | Chewing ability test | 14 | 29% |

| 7 | Swallowing (EAT-10) | 4 | 8% |

| Total (n = 50) | Male (n = 35) | Female (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased grip strength | Number | 46 | 34 | 12 |

| Male < 28 kg; Female < 18 kg | Prevalence | 92% | 97% | 80% |

| Locomotive syndrome | Number | 45 | 32 | 13 |

| Two-step test < 1.3 | Prevalence | 90% | 91% | 87% |

| Short physical performance battery (SPPB) | Number | 18 | 13 | 5 |

| 8≥ | Prevalence | 36% | 37% | 33% |

| AI analysis of gait | Number | 25 | 18 | 7 |

| 16≥ | Prevalence | 50% | 51% | 47% |

| Total | Oral Frailty + | Oral Frailty − | Oral Dysdiadochokinesis | pa | ta | ka | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robust | 5 | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | 5 (100%) | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Locomotive syndrome | 45 | 32 (71%) | 13 (29%) | 45 (100%) | 40 | 40 | 45 |

| Mild 0.9–1.3 | 21 | 16 | 5 | 21 | 17 | 18 | 21 |

| Severe 0.9> | 24 | 16 | 8 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 24 |

| Total | 50 | 33 (66%) | 17 (34%) | 50 (100%) | 44 | 45 | 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ina, K.; Tenma, M.; Makino, S.; Yonemochi, T.; Nagasaka, M.; Kabeya, M.; Morishita, Y.; Fuwa, D.; Nanbu, T.; Takahashi, A.; et al. Oral Frailty and Its Association with Cognitive Function and Muscle Strength in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Retrospective Observational Study. Kidney Dial. 2025, 5, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5040051

Ina K, Tenma M, Makino S, Yonemochi T, Nagasaka M, Kabeya M, Morishita Y, Fuwa D, Nanbu T, Takahashi A, et al. Oral Frailty and Its Association with Cognitive Function and Muscle Strength in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Retrospective Observational Study. Kidney and Dialysis. 2025; 5(4):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5040051

Chicago/Turabian StyleIna, Kenji, Miki Tenma, Shinya Makino, Toshie Yonemochi, Miki Nagasaka, Megumi Kabeya, Yoshihiro Morishita, Daisuke Fuwa, Takayuki Nanbu, Ayako Takahashi, and et al. 2025. "Oral Frailty and Its Association with Cognitive Function and Muscle Strength in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Retrospective Observational Study" Kidney and Dialysis 5, no. 4: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5040051

APA StyleIna, K., Tenma, M., Makino, S., Yonemochi, T., Nagasaka, M., Kabeya, M., Morishita, Y., Fuwa, D., Nanbu, T., Takahashi, A., Ito, K., & Ohta, Y. (2025). Oral Frailty and Its Association with Cognitive Function and Muscle Strength in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Retrospective Observational Study. Kidney and Dialysis, 5(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5040051