Abstract

Hypomagnesaemia, a common complication ranging from 20% to over 90%, depending on the diagnostic criteria and population studied, significantly contributes to adverse outcomes, including new-onset diabetes after transplantation, cardiovascular complications, neurological dysfunction and increased infection risk. A total serum magnesium below 0.70 mmol/L is commonly used to define deficiency. In kidney transplant recipients, calcineurin inhibitors downregulate TRPM6 in the distal nephron, leading to early and persistent hypomagnesaemia with links to adverse metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes. Arrhythmia risk rises steeply at total magnesium of <0.50 mmol/L, while neuromuscular irritability and neuropsychiatric symptoms may appear at levels below 0.70 mmol/L. Severe manifestations, such as seizures or tetany, usually occur at ≤0.50 mmol/L and coma at <0.30 mmol/L. Normal ionised magnesium is typically ~0.48–0.65 mmol/L; transplant-specific intervention thresholds remain unvalidated. This narrative review addresses critical diagnostic gaps and explores emerging therapeutic strategies. It highlights three areas: the diagnostic accuracy of ionised magnesium over total magnesium, the critical role of pharmacogenomics in individualising immunosuppression to mitigate tacrolimus-induced hypomagnesaemia and the promising link between gut microbiome modulation and magnesium homeostasis. The implications of these insights are profound: enabling more precise diagnosis and personalised management, reducing the incidence and severity of hypomagnesaemia-related complications, and ultimately supporting more precise diagnosis and personalised management; prospective validation in transplant cohorts is required before outcome claims can be made. This review exposes current diagnostic and therapeutic limitations, advocating for more precise and personalised strategies to address this critical electrolyte imbalance. Identifying hypomagnesaemia as a mechanistically complex and clinically undertreated complication, this review proposes a thematic roadmap that serves as a scientific and clinical framework for advancing personalised electrolyte care in renal transplantation. It is emphasised that while these approaches appear promising, most remain under-evaluated or hypothesis-generating. Addressing hypomagnesaemia through validated thresholds, new research is required to test novel diagnostics and personalised strategies to improve patient and graft outcomes.

1. Introduction

Renal transplantation represents an optimal treatment for patients diagnosed with renal failure, offering improved survival and quality of life compared to dialysis [1]. However, the post-transplant period is characterized by numerous metabolic complications, among which hypomagnesaemia stands out as a particularly prevalent and clinically significant electrolyte disturbance. The incidence of hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients ranges from 20% to 90%, with this wide variation reflecting differences in diagnostic criteria, patient populations, and immunosuppressive regimens [2].

Compared to the general ward population, renal-transplant recipients lose magnesium (Mg) at serum levels relatively higher than non-renal transplant patients due to calcineurin-inhibitor-induced related tubular (TRPM6) down-regulation. The pathophysiology of hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients is multifactorial, involving both medication-induced and transplant-specific factors. Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), the cornerstone of immunosuppressive therapy, are well-established causes of renal Mg wasting through their effects on the distal convoluted tubule [3,4]. Additionally, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), frequently prescribed for gastroprotection, contribute to Mg deficiency through impaired intestinal absorption [5]. Other contributing factors include diuretic use, diabetes mellitus, and the inherent dysfunction of the transplanted kidney [2]. Transplant recipients experience neurological/cardiac symptoms at higher Mg levels than the general population due to medication synergism and baseline CKD metabolic bone disease (MBD). Their increased susceptibility to hypomagnesaemia and its complications necessitate a more proactive and often more aggressive approach to maintaining adequate Mg levels.

Mg, an essential intracellular cation, plays a crucial role in numerous physiological processes, including neuromuscular conduction, cardiac electrophysiology, and enzymatic reactions [1]. Hypomagnesaemia, or Mg deficiency, is a common electrolyte imbalance that can lead to a wide range of clinical manifestations. Defining this condition precisely is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management, particularly in high-risk populations such as renal transplant recipients. Hypomagnesaemia is broadly defined as a serum Mg level below 0.74 mmol/L [6]. Some classifications consider levels below 0.66 mmol/L as typical for hypomagnesaemia [7]. Clinical manifestations, while possible at higher levels, often become more pronounced when serum Mg concentrations fall below 0.5 mmol/L [6,7]. Severe hypomagnesaemia can be characterized by plasma Mg levels below 0.3 mmol/L [8]. It is important to note that many patients may remain asymptomatic despite biochemical evidence of hypomagnesaemia [6]. In the UK, while there is not a single universally agreed-upon national guideline for specific serum Mg reference ranges, hypomagnesaemia is commonly diagnosed when levels fall below 0.7 mmol/L [9]. Serum Mg reference ranges can vary widely among different institutions and laboratories, and some propose a low cut-off point of 0.85 mmol/L to define hypomagnesaemia to prevent underdiagnosis [9].

Clinical decisions within the UK National Health Service (NHS) regarding Mg replacement typically consider these general reference ranges, along with patient symptomatology and underlying risk factors. For renal transplant recipients, a more proactive approach is often warranted, and intervention may be considered at levels that are at the lower end of the normal range or even slightly below, given their increased susceptibility to complications and the impact of their medications.

The accurate diagnosis of hypomagnesaemia is crucial for effective management, yet it presents significant challenges due to the limitations of commonly used diagnostic methods. Traditional reliance on total serum magnesium (tMg) measurements can be misleading, particularly in patient populations with altered protein binding, such as renal transplant recipients who frequently experience hypoalbuminemia [6]. Mg exists in the blood in three forms: protein-bound (approximately 30%), complexed with anions (approximately 15%), and free or ionized (approximately 55%) [9]. It is the ionized magnesium (iMg) that represents the physiologically active form of the electrolyte, responsible for its numerous biological functions. Therefore, iMg offers a more accurate assessment of true Mg status compared to tMg [2,7]. Several studies highlight the diagnostic superiority of iMg:

- −

- Masked Deficiency: Low iMg levels can exist despite normal tMg, leading to delayed diagnosis and potentially exacerbated complications [4,6]. This discrepancy is particularly relevant in recipients with hypoalbuminemia, where a significant portion of tMg may be bound to albumin, masking an underlying deficiency in the active, unbound form [6].

- −

- Predictive Value: iMg has demonstrated superior predictive value for clinical outcomes, including new-onset diabetes after transplantation (PTDM) and cardiovascular events, compared to tMg [2,4].

- −

- Clinical Relevance: While tMg remains the dominant test in many centres due to historical precedent and broader availability, the clinical relevance of iMg is increasingly recognised. The proposed normal reference range for iMg is typically cited as 0.48–0.65 mmol/L [10].

While tMg provides a general indication of Mg status, iMg offers a more precise and physiologically relevant measure, particularly in complex patient populations like renal transplant recipients. Advocating for broader implementation and availability of iMg testing is crucial for improving diagnostic accuracy and facilitating timely, personalized interventions.

In the UK, around 2500 renal transplants are performed annually, with a waiting list of around 8096 patients [11]. Hypomagnesaemia, defined as a serum Mg concentration below 0.70 mmol/L, is a prevalent electrolyte abnormality in renal transplant recipients, affecting between 10% and over 90% of recipients, depending on the diagnostic criteria and population studied [12,13]. Its etiology is multifactorial, primarily driven by calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) therapy, particularly tacrolimus, which induces renal Mg wasting [14,15]. Other contributing factors include delayed graft function, diuretic use, proton pump inhibitors, and pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions [16,17]. Despite its high incidence, hypomagnesaemia is often overlooked, yet it significantly contributes to a range of adverse clinical outcomes, including new-onset diabetes after transplantation (PTDM), cardiovascular complications, neurological dysfunction, and increased risk of infections [18,19,20].

Despite its clinical importance, there is currently no universally accepted threshold for Mg replacement in post-renal transplant recipients—a gap that hinders standardised care and inter-centre comparability. In a recent systematic review [4], the author concluded that studies prospectively evaluating the impact of hypomagnesaemia correction after kidney transplantation are still lacking and needed. Management of post-transplant hypomagnesaemia must account for polypharmacy and coexisting conditions that amplify Mg loss or impair absorption. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce intestinal Mg uptake through effects on TRPM6/TRPM7 channels; chronic use is a recognised risk factor for clinically significant deficiency. Loop and thiazide diuretics exacerbate renal Mg wasting, often compounding the effects of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs). Aminoglycosides and amphotericin B induce tubular injury and Mg leakage, while commonly used over-the-counter antacids may alter gastrointestinal handling in unpredictable ways. Importantly, tacrolimus typically lowers Mg levels more than ciclosporin, reflecting its distinct impact on distal tubular reabsorption. Beyond pharmacology, comorbidities such as chronic diarrhoeal illness, malabsorption syndromes (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, short bowel), malnutrition, and alcoholism represent important contributors to persistent hypomagnesaemia. In patients with refractory deficiency, a structured evaluation for these causes is warranted, as Mg supplementation alone may be insufficient without addressing underlying pathology. Recognition of these additive risks is essential to designing an effective and personalised replacement strategy. Monitoring Mg levels and separation between dosing of Mg supplements and other medications by two hours should be considered [21].

This narrative review synthesizes current understanding and highlights the authors’ perspectives on hypomagnesaemia in post-renal transplant patients. It explored recent advancements in diagnostic approaches, emerging pathophysiological insights, and discussed innovative therapeutic strategies, with a particular focus on areas that represent significant novelty and potential for improved patient outcomes. It seeks to provide a comprehensive and updated overview of hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients, addressing key knowledge gaps and proposing future directions for research and clinical practice.

2. Objectives and Main Message

This review has three objectives:

- To consolidate the mechanistic understanding of hypomagnesaemia after kidney transplantation, with emphasis on calcineurin inhibitor effects, drug interactions, and comorbid contributors.

- To appraise current and emerging diagnostic approaches—including iMg, albumin-adjusted Mg, and threshold-based definitions—and clarify which remain under-utilised rather than truly novel.

- To explore management strategies ranging from conventional supplementation to pharmacogenomic- and microbiome-informed approaches, while distinguishing validated interventions from hypothesis-generating concepts.

Main message: Hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients is highly prevalent, mechanistically complex, and clinically consequential. While innovations such as iMg monitoring, genotype-guided immunosuppression, and microbiome modulation are promising, these remain largely unvalidated. While recognising that, in transplant recipients, symptom expression correlates imperfectly with tMg and is shaped by concomitant medications and electrolyte abnormalities.

3. Methods

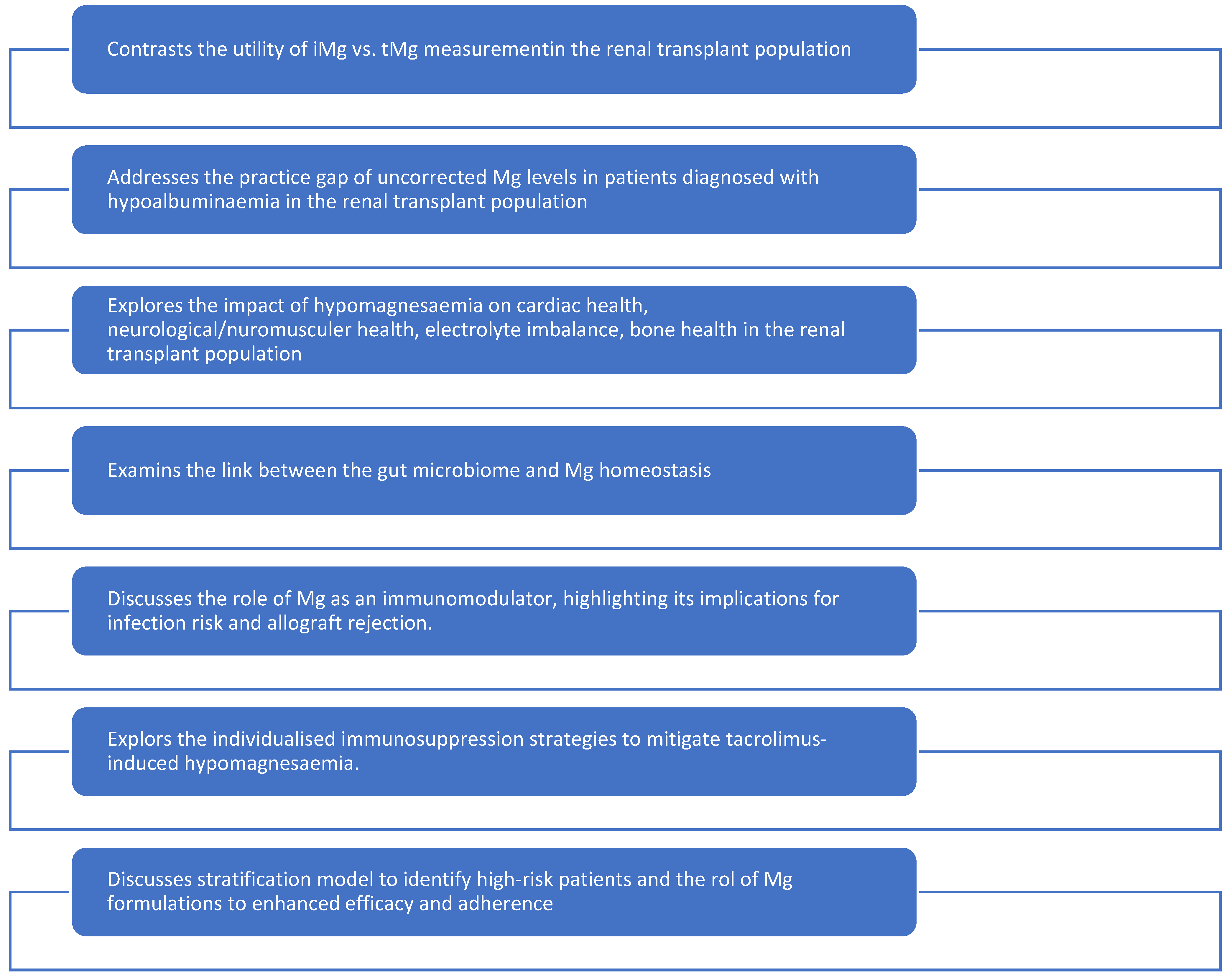

This narrative review was conducted through a comprehensive literature search across PubMed®, Scopus®, and Web of Science® databases. Keywords included “hypomagnesaemia”, “renal transplant”, “kidney transplantation”, “magnesium deficiency”, “tacrolimus”, “cyclosporine”, “immunosuppression”, “ionized magnesium”, “gut microbiome”, “pharmacogenomics”, “bone health” and “cognitive function”. Thirty-two studies were selected for detailed review, ensuring a balance between foundational knowledge and recent advancements. Studies were included if they involved adult renal transplant recipients and reported on Mg levels, mechanisms, diagnostic methods, clinical outcomes, or therapeutic interventions. Single-patient anecdotes without biochemical data, non-English studies without translation, and reports outside the transplant setting were excluded unless mechanistically indispensable. Priority was given to studies published in English within the past 10 years, including both foundational and novel research relevant to transplant-specific hypomagnesaemia. It is noteworthy that none of the reviewed literature clearly stated a definitive threshold for Mg replacement that addresses all the presented points in detail. This narrative review was structured based on seven critical themes that represent the cutting edge of research and clinical practice in this area Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Narrative review structure.

4. Discussion

This is a narrative review designed for interpretive synthesis and hypothesis generation rather than systematic meta-analysis. Our clinical perspective as nephrology clinicians may introduce emphasis toward transplant-specific implications, but sufficiency was judged met given the convergence of evidence across multiple study types. Table 1 provides a summary of each key proposal, its evidence base, and validation status.

Table 1.

Current diagnostic evidence vs. Hypothesis.

4.1. Ionized vs. Total Magnesium

Quantitative thresholds for intervention are particularly important in transplant care. In the general population, cardiovascular risk increases once serum Mg falls below 0.70 mmol/L, with severe arrhythmias typically observed below 0.50 mmol/L. Neurological symptoms such as cramps, irritability, and anxiety are seen at <0.70 mmol/L, whereas tetany and seizures emerge at ≤0.50 mmol/L. Reports of coma or profound neurological dysfunction occur almost exclusively at <0.30 mmol/L. Importantly, transplant recipients appear to develop these manifestations at slightly higher Mg levels than non-transplant comparators, supporting the argument for earlier intervention in this group. The clinical relevance of iMg lies in its ability to detect deficiencies masked by normal tMg, particularly when levels are near these clinical thresholds [11,12,13].

Traditional reliance on total serum magnesium (tMg) can be misleading, especially in renal transplant recipients who are also diagnosed with hypoalbuminaemia. Despite the known biological superiority of iMg, tMg remains the dominant test in many centres due to historical precedent and limited access to iMg testing. iMg, the free and biologically active form, offers a more accurate assessment of true Mg status [22,23,24]. Studies show that low iMg can exist despite normal tMg, leading to delayed diagnosis and exacerbated complications [25,26,27]. iMg also demonstrated superior predictive value for outcomes like new-onset diabetes after transplantation (PTDM) and cardiovascular events [24,27]. A refined, tiered monitoring strategy is proposed: routine tMg screening followed by targeted iMg measurement in high-risk scenarios (e.g., persistent hypomagnesaemia, clinical symptoms with normal tMg, high-dose CNIs, or significant hypoalbuminemia). This could provide personalized management, guide precise replacement strategies and facilitate accurate risk stratification [26,28,29,30]. Gaining broader implementation may require advocacy for reimbursement and wider availability of point-of-care iMg analysers.

4.2. Hypoalbuminemia and Uncorrected Magnesium

To address the practice gap of uncorrected Mg levels in patients with hypoalbuminemia, widespread adoption of validated albumin-adjusted Mg formulas has been recommended as an interim solution [6]. However, it is important to note that these formulas are approximations and do not replace the diagnostic precision of direct iMg measurement. Routine iMg measurement, especially in high-risk scenarios such as persistent hypomagnesaemia, clinical symptoms with normal tMg, high-dose CNI therapy, or significant hypoalbuminemia, is advocated for personalized management and accurate risk stratification [3,4].

Use of uncorrected total serum Mg levels in patients with hypoalbuminaemia may mask deficiency, as low albumen is common in transplant recipients [31]. Delayed diagnosis risks exacerbating PTDM, cardiovascular events, and neurological symptoms. Widespread adoption of validated albumin-adjusted Mg formulas is recommended as an interim solution. These formulas are approximations and do not replace the diagnostic precision of direct iMg measurement. Routine iMg measurement in all hypoalbuminaemia states remains the definitive approach [24,27]. This practice change would facilitate precise diagnosis and enhance patient safety.

Routine use of albumin-adjusted Mg levels coupled with iMg in renal transplant patients with hypoalbuminaemia may prevent misdiagnosis.

4.3. Hypomagnesaemia in Renal Transplant Population

4.3.1. Cardiac Symptoms Manifestations

Mg plays a pivotal role in maintaining normal cardiac electrophysiology. Its deficiency can lead to a range of cardiac abnormalities, from subtle changes in repolarization to life-threatening arrhythmias (Table 2). Understanding the specific Mg thresholds at which these cardiac symptoms manifest is crucial for timely intervention and prevention of adverse outcomes in renal transplant recipients [3,4,5,6,7,10,16,32,33,34,35].

Table 2.

Cardiac symptoms due to hypomagnesaemia.

Hypomagnesaemia is a well-established risk factor for various cardiac arrhythmias, including QT interval prolongation and the potentially fatal polymorphic ventricular tachycardia known as torsades de pointes (TdP) [32,33]. In a meta-analysis of >150,000 individuals [10], the odds of QT prolongation increased continuously below 0.70 mmol/L; however, the steepest rise occurred <0.50 mmol/L (OR 2.4, 95 per cent CI 1.8–3.1). This highlights a critical threshold for severe cardiac manifestations.

In renal transplant recipients, immunosuppressive therapies and comorbidities can modify susceptibility to complications; magnesium levels at the lower end of the reference range (e.g., 0.7–0.8 mmol/L) may justify closer monitoring in the presence of additional risk factors or symptoms, but specific intervention thresholds are not established. While total serum Mg is the most measured parameter, iMg represents the physiologically active form of the electrolyte and is arguably more relevant for assessing its impact on cellular functions, including cardiac electrophysiology. In transplant populations, where hypomagnesaemia is particularly prevalent, the assessment of iMg levels is especially pertinent [10]. The proposed normal reference range for iMg is typically cited as 0.48–0.65 mmol/L [10]. Although a precise iMg cut-off for arrhythmia prevention in kidney transplant recipients has yet to be definitively established, multiple reviews consistently confirm a strong association between hypomagnesaemia and an increased risk of both ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, including TdP and atrial fibrillation [10].

4.3.2. Neurological and Neuromuscular Manifestations

Mg deficiency profoundly affects the nervous system, leading to a spectrum of neurological and neuromuscular symptoms that can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and clinical outcomes. The neurological manifestations of hypomagnesaemia range from subtle symptoms such as irritability and fatigue to severe complications, including seizures and tetany (Table 3). Understanding the specific Mg thresholds at which these symptoms occur is essential for timely recognition and intervention in renal transplant recipients [1,6,16,34,35,36].

Table 3.

Neurological symptoms due to hypomagnesaemia.

Neuromuscular irritability represents one of the earliest and most characteristic manifestations of Mg deficiency. This occurs due to Mg’s critical role in regulating neuromuscular excitability through its effects on calcium channels and membrane stability [6]. Muscle cramps, fasciculations, and hyperreflexia typically begin to manifest when serum Mg levels fall below 0.7 mmol/L [6,7]. These symptoms may be subtle initially and easily overlooked in the complex clinical context of post-transplant care. In renal transplant recipients, these symptoms may emerge at slightly higher Mg levels due to their underlying vulnerabilities and medication effects, necessitating earlier consideration for intervention. More severe neuromuscular manifestations, including tetany with positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs, typically occur when serum Mg levels drop below 0.5 mmol/L [6,7]. Tetany may be difficult to distinguish from hypocalcaemia-induced tetany, as Mg deficiency often coexists with and contributes to hypocalcaemia through impaired parathyroid hormone secretion and action [7]. Severe neuromuscular irritability manifesting as carpopedal spasm has been reported at serum Mg levels below 0.4 mmol/L [8].

Mg deficiency can lead to serious central nervous system complications, with seizures representing the most severe manifestation. The anticonvulsant properties of Mg are well-established, and its deficiency can lower the seizure threshold significantly [8]. Across five transplant cohorts, seizures were reported exclusively at serum Mg ≤ 0.54 mmol/L (1.3 mg/dL); 88 per cent of cases occurred at serum Mg ≤ 0.50 mmol/L [37].

- −

- Seizure Risk: Seizures associated with hypomagnesaemia typically occur when serum levels fall below 0.5 mmol/L, though individual susceptibility varies considerably [6,7]. In renal transplant recipients, the risk may be further elevated due to concurrent use of medications that lower the seizure threshold, such as certain immunosuppressive agents. Therefore, a proactive approach to Mg repletion may be warranted even at levels slightly above 0.5 mmol/L if other risk factors for seizures are present.

- −

- Neuropsychiatric Symptoms: Depression, anxiety, irritability, and confusion can occur at serum Mg levels below 0.7 mmol/L [6]. These symptoms may be particularly relevant in renal transplant recipients, who already face increased risks of neuropsychiatric complications due to immunosuppressive therapy and the stress of chronic illness.

- −

- Severe CNS Manifestations: Coma and severe neurological dysfunction have been reported in cases of severe hypomagnesaemia with serum levels below 0.3 mmol/L [8].

4.3.3. Concurrent Electrolyte Abnormalities

Hypomagnesaemia rarely occurs in isolation and frequently coexists with other electrolyte abnormalities that can compound neurological symptoms. Understanding these interactions is crucial for effective management in renal transplant recipients. Hypomagnesaemia impairs parathyroid hormone secretion and reduces target organ responsiveness to PTH, leading to hypocalcaemia that is refractory to calcium supplementation alone [7]. This interaction means that neurological symptoms may persist despite calcium replacement. Hypomagnesaemia can also contribute to renal potassium wasting, leading to concurrent hypokalaemia that may exacerbate neuromuscular symptoms [6]. In renal transplant recipients, this interaction is particularly relevant given the frequent use of diuretics.

4.4. Gut Microbiome and Magnesium Homeostasis

Emerging evidence suggests a link between disturbance in gut microbiome and impaired intestinal Mg absorption [38,39]. The gastrointestinal microbiome is affected by immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and underlying kidney disease. This is reported to compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier and alter the function of Mg transporters [40]. Evidence is limited, but further research on the use of probiotics, prebiotics, or dietary modifications may lead to adjunctive therapies to optimize Mg levels [38,39]. Lactobacillus reuteri has been shown to influence Mg absorption through production of short-chain fatty acids, acidifying the luminal environment, enhancing Mg solubility and uptake. Conversely, an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria or a reduction in beneficial flora can disrupt these processes, reducing Mg absorption. Clinical trials in renal transplant recipients are limited, but the potential for probiotics or prebiotics to restore gut balance and maintain Mg status appears promising. This may provide an alternative, or adjunct to, Mg supplementation.

4.5. Bone Health and Cognitive Function

Mg is vital for both bone health and neurological function. Renal transplant recipients face high risks of bone mineral density loss and fractures due to chronic kidney disease-related metabolic bone disease (CKD-MBD) and immunosuppression. Chronic hypomagnesaemia exacerbates bone demineralization and increases fracture risk [41,42]. Mg is involved in the modulation of nerve transmission, and deficiency produces neurological symptoms [43,44]. The link between low Mg and cognitive impairment in transplant patients requires further research. Mg is crucial for preserving bone health, managing symptoms such as muscle cramps, and potentially improving cognitive outcomes [43,44]. The role of Mg in bone health is well-established. Mg is integral to bone structure, and deficiency can impair formation and increase resorption. In renal transplant recipients, this risk is further compounded by pre-existing chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD), the use of immunosuppressive medications (e.g., corticosteroids), and other metabolic derangements. Chronic hypomagnesaemia can also lead to parathyroid hormone (PTH) dysregulation, contributing to secondary hyperparathyroidism, which further exacerbates bone turnover abnormalities. Maintaining Mg levels is important in preserving skeletal integrity and preventing fragility fractures in vulnerable populations. It is also essential to neuronal function. It inhibits cellular calcium channels, regulating excitation and synaptic transmission. Deficiency may manifest as tremors, muscle cramps, and seizures, and emerging evidence suggests effects on cognitive function. Hypomagnesaemia has been linked to memory impairment, attention deficit, and anxiety. Direct studies of the neurocognitive impact of chronic hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant patients are limited but warrant further research. Prevention of deficiency may be a modifiable factor to preserve cognitive health and improve overall quality of life in renal transplant recipients.

4.6. Immunomodulatory Role of Magnesium

Mg plays a direct role in immune regulation and inflammatory responses. It is essential for immune cell function, activation, and proliferation [45,46]. Mg deficiency can impair immune competence, increase susceptibility to infections and potentially influence allograft rejection [45,46]. Maintaining optimal Mg levels can support immune function and reduce adverse immunological outcomes, highlighting the need for careful monitoring and balanced supplementation [45,46].

Mg is a cofactor for a number of enzymes involved in the signalling and functioning of cellular immunity, including T-lymphocyte activation, antibody production by B-lymphocytes, and phagocytic activity of macrophages. It influences the inflammatory response by modulating the activity of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), a regulator of pro-inflammatory gene expression. Hypomagnesaemia can exaggerate the inflammatory response, tissue damage and exacerbation of allograft nephropathy. Maintenance of Mg homeostasis will conversely reduce the inflammatory response.

In renal transplantation, patients are inherently immunocompromised with immunosuppressive therapy. Mg deficiency can further compromise their immune response. This supports the hypothetical association of hypomagnesaemia with increased acute rejection episodes. Whilst a logical theory, this linkage requires further research. However, it further supports that maintaining optimal Mg levels is a component of immune support in renal transplant recipients.

4.7. Pharmacogenomics of Tacrolimus-Induced Hypomagnesaemia

The unpredictable occurrence of tacrolimus-induced hypomagnesaemia suggests a genetic predisposition. Polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP3A5 and CYP3A4 influence tacrolimus pharmacokinetics and, consequently, the risk of hypomagnesaemia [47,48,49]. Use of genetic testing to identify high-risk patients would allow tailored tacrolimus dosing and proactive Mg monitoring [48,49]. The genetics of tacrolimus-induced hypomagnesaemia extends beyond enzymes employed in its metabolism to include transporters and cellular channels involved in Mg homeostasis. The TRPM6 gene encodes a transient receptor potential melastatin type 6 channel involved in intestinal Mg absorption and renal reabsorption. Polymorphisms of this gene affect susceptibility to hypomagnesaemia. Variations in the ABCB1 (MDR1) gene, encoding P-glycoprotein, an efflux transporter that influences tacrolimus disposition, may also indirectly affect Mg levels by altering intracellular tacrolimus concentrations in renal tubular cells. While CYP3A5 activity can be measured and is clinically useful, to date, TRPM6 and ABCB1 remain investigational. A greater understanding of these genetic variations would allow individualised patient management. An individualised approach would optimise the immunosuppression whilst reducing or preventing the incidence of hypomagnesaemia. This is a promising but evolving tool for personalised management. We also like to highlight that the frequency variability of CYP3A5, TRPM6 and ABCB1 limits generalisability. Genotype-guided dosing relevance will vary by ancestry.

4.8. Clinical Implications and Proposed Framework

The evidence presented in this review has significant implications for clinical practice in renal transplant recipients. The identification of specific Mg thresholds for cardiac and neurological symptoms provides a foundation for developing evidence-based protocols for Mg monitoring and replacement therapy within the UK NHS framework.

4.8.1. Risk Stratification Models—Conceptual Prototype and Not for Clinical Use

It is worth noting that the three possible stratification models are yet to be validated. The high prevalence and clinical consequences of hypomagnesaemia necessitate effective risk-stratification tools. Despite identified risk factors (CNI type/dose, Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), diuretics, diabetes), a universally validated predictive risk score for hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant patients is lacking [50]. Future models should integrate clinical, biochemical, and genetic parameters, including iMg measurements, to accurately stratify risk, guide personalized management, and improve long-term outcomes [50]. To address this critical gap, a novel 5-factor risk scoring model for hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients is proposed. This model integrates readily available clinical and laboratory parameters with emerging genetic insights to provide a comprehensive assessment of individual patient risk. Each factor would have an assigned weighted score based on its established contribution to hypomagnesaemia risk, allowing for a cumulative risk score. For instance, a patient with high tacrolimus levels, hypoalbuminemia, low ionized Mg, concurrent PPI use, and a high-risk TRPM6 genotype would accumulate a higher score, indicating a significantly elevated risk of developing or experiencing severe hypomagnesaemia.

- −

- Tacrolimus level (higher trough levels indicate increased exposure or rapid metabolism, reducing exposure)

- −

- Albumin levels (hypoalbuminemia increases the risk of uncorrected hypomagnesaemia)

- −

- Ionized Mg levels (as a direct measure of biologically active Mg)

- −

- Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) use (a known contributor to Mg malabsorption)

- −

- TRPM6 gene status (identifying genetic predisposition to renal Mg wasting)

Another possible stratification model can be based on the level of risk. Based on the evidence reviewed, renal transplant recipients can be stratified into different risk categories for Mg-related complications:

- −

- High Risk: Patients receiving high-dose CNI therapy, concurrent PPI use, diabetes mellitus, or those with a history of Mg-related complications. These patients should undergo more frequent monitoring with consideration for iMg measurement when available.

- −

- Moderate Risk: All renal transplant recipients have a high prevalence of hypomagnesaemia in this population. Regular monitoring of serum Mg levels should be incorporated into routine post-transplant care.

- −

- Low Risk: Patients with consistently normal Mg levels and no additional risk factors may require less frequent monitoring, though vigilance should be maintained given the potential for rapid changes in Mg status.

Stratification can also be made based on Mg threshold-based intervention. Based on the evidence synthesized in this review, the following threshold-based approach can be considered for Mg replacement in renal transplant recipients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Integrated Evidence Map.

4.8.2. Magnesium Formulation Optimisation

Current approaches to Mg supplementation are poorly absorbed and frequently limited by gastrointestinal side effects. Novel formulations such as sucrosomial Mg offer enhanced absorption and reduced side effects by bypassing traditional intestinal pathways [54,55]. Sustained-release preparations and transdermal applications also show promise. Comparative effectiveness studies are needed to evaluate these formulations for improved Mg repletion and patient adherence [54,55]. The suboptimal function and side effects of most current supplements often lead to poor adherence and discontinuation. This is compounded in renal transplant recipients who receive multiple medications and may have altered gastrointestinal function due to immunosuppressants and/or underlying conditions.

Sucrosomial Mg encapsulates Mg oxide within a sucrosomial membrane, allowing absorption through different intestinal pathways. It provides better bioavailability and fewer and less severe gastrointestinal side effects. Sustained-release formulations are designed to release Mg gradually over an extended period, which can also enhance absorption and minimize peak concentrations that may be associated with adverse effects. Although additional rigorous clinical studies are needed, transdermal Mg provides an alternative to oral administration that may be advantageous for patients experiencing significant gastrointestinal complications or malabsorption. Although these innovative formulations show potential, additional clinical validation in transplant recipients is required.

While sustained-release oral preparations and sucrosomial Mg show early signals of improved bioavailability and tolerability, the role of transdermal Mg remains uncertain. Evidence to date is limited to small, non-transplant studies with inconsistent outcomes, and no robust clinical trials have confirmed efficacy or safety in renal transplant populations. Transdermal Mg remains investigational, with no robust transplant data; therefore, it should be regarded as an investigational adjunct rather than established therapies, and its use in practice should be accompanied by caution and close monitoring until further evidence emerges. Mg formulations with enhanced bioavailability and reduced side effects may significantly improve patient adherence and the effectiveness of Mg repletion strategies in renal transplant recipients.

4.8.3. Standardised Data Collection Across Transplant Centres

Hypomagnesaemia research and management are hindered by inconsistent data collection among transplant centres, making it difficult to compare studies, combine results, and establish broadly applicable guidelines. To overcome this, there is an urgent need for the establishment of standardized data collection protocols. These protocols should specify the minimum dataset required for each renal transplant recipient, including detailed information on immunosuppressive regimens (type, dose, trough levels), Mg supplementation (type, dose, duration), baseline and serial total and ionized Mg levels, albumin levels, and the occurrence of hypomagnesaemia-related complications. Standardised data collection would enable the creation of large, multi-center registries, allowing researchers to pool data, identify trends, validate risk models, and evaluate interventions more effectively. Such collaboration is vital to accelerate research, apply findings clinically, and improve care for renal transplant recipients worldwide, requiring coordinated efforts across institutions.

5. Limitations

This narrative review, while comprehensive in its scope, is subject to certain inherent limitations. The very nature of a narrative review dictates that it does not involve a systematic assessment of study quality or a quantitative synthesis of findings, distinguishing it from a systematic review or meta-analysis. While we diligently aimed to include the most relevant and high-quality studies, the selection process was not exhaustive and may, by its design, be subject to reviewer bias. Furthermore, the rapid evolution of research in dynamic areas such as pharmacogenomics and the gut microbiome implies that some of the most nascent emerging evidence may not have been fully captured within the scope of this review. Crucially, the persistent absence of a clear, universally accepted threshold for Mg replacement in the existing literature highlights a significant and unresolved knowledge gap that this review, despite discussing novelties, cannot definitively resolve. It is worth noting that while Sex-specific thresholds for Mg might differ between men and women. At present, we cannot include it as current evidence is insufficient to define sex-specific thresholds in transplant cohorts, and we would like to flag this as a future research priority. The findings synthesised in this review may not be universally applicable to all renal transplant populations. Many of the included studies derive from single-centre cohorts in Europe, North America, or Asia, with limited representation of African, South Asian, or resource-limited settings. Inter-ethnic variability is particularly relevant to pharmacogenomic proposals: for example, CYP3A5*1 allele frequency is markedly higher in African ancestry populations compared to European or East Asian cohorts, influencing tacrolimus metabolism and downstream Mg handling. Similarly, TRPM6 and ABCB1 polymorphisms show heterogeneous distribution across ancestries, which constrains the generalisation of “personalised dosing” strategies. Without adequately powered, multi-ethnic validation studies, these approaches must be regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than directly translatable. Paediatric and multi-organ transplant recipients are also under-represented in the literature, further limiting the scope. We therefore frame our conclusions as applicable mainly to adult, single-organ kidney transplant cohorts in high-resource settings, while highlighting broader representativeness as a research priority. This review serves as a call to action for further rigorous research to address these critical limitations and advance the field.

6. Future Directions

Future research should focus on establishing an evidence-based, widely accepted threshold for Mg replacement in renal transplant patients, considering both total and ionized Mg levels. Large-scale, multi-center studies are needed to validate ionized Mg monitoring and its role in guiding personalized supplementation.

Additionally, studies of the pharmacogenomics of tacrolimus-induced hypomagnesaemia, examining CYP3A5, CYP3A4, TRPM6, ABCB1, and other relevant genetic variants, are required. These studies should clarify genotype-phenotype correlations and evaluate the effects of genotype-guided dosing on hypomagnesaemia and patient outcomes.

Research exploring the precise mechanisms by which the gut microbiome influences Mg homeostasis and the potential for targeted microbial interventions (e.g., specific probiotics or prebiotics) to improve Mg status is also warranted. This emerging field requires rigorous clinical trials to identify effective microbial strains and dosages, and to understand their long-term impact on Mg absorption and overall patient health.

Longer-term studies are needed to evaluate the effects of optimized Mg levels on bone health, neurocognitive function, and immune competence among renal transplant recipients. Integrating patient perspectives into future research may provide valuable insights into real-world challenges affecting Mg adherence and overall quality of life. The development of standardized data collection protocols across international transplant centres would enable robust comparative effectiveness research and expedite the creation of evidence-based guidelines for hypomagnesaemia management. The implementation of initiatives such as a global registry dedicated to Mg-related data in transplant patients could greatly enhance data aggregation, facilitate the identification of meaningful trends, and drive ongoing quality improvement.

7. Conclusions

Requesting and interpreting iMg in renal transplant patients would facilitate early detection and appropriate management of Mg. Hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients is driven primarily by calcineurin inhibitor–induced renal wasting, compounded by polypharmacy (PPIs, diuretics, antimicrobials) and comorbidities such as malabsorption or malnutrition. Genetic polymorphisms (e.g., CYP3A5, TRPM6, ABCB1) likely modulate individual susceptibility but remain under-investigated. Ionised Mg offers superior diagnostic accuracy over total Mg, particularly in hypoalbuminaemia, yet is rarely implemented. Albumin-adjusted formulas are underutilised. Clinical symptoms in transplant recipients often appear at higher Mg levels (0.7–0.8 mmol/L) than in the general population, reinforcing the need for vigilance monitoring. Current supplementation strategies are limited by poor absorption and tolerability. Novel oral formulations (e.g., sucrosomial, sustained-release) show early promise, but transplant-specific validation is lacking. Transdermal Mg remains investigational only. A five-factor risk model has been proposed, but it must be regarded as conceptual until prospectively tested. Hypomagnesaemia remains an under-recognised yet clinically consequential complication after kidney transplantation, affecting cardiovascular, neurological, immunological, and skeletal outcomes. While the field is rich in hypotheses and emerging approaches, few have crossed into validated clinical practice.

Modulating the gut microbiome through targeted interventions like specific probiotics or prebiotics may offer a novel adjunctive strategy to improve Mg homeostasis and address hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients, especially in cases of impaired intestinal absorption. Proactive management of hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients may preserve long-term bone health and prevent neurocognitive decline. Optimizing Mg levels in renal transplant recipients may be crucial for supporting immune function, reducing susceptibility to infections, and potentially mitigating the risk of allograft rejection, thereby contributing to improved long-term patient and graft outcomes. Greater use of individualised dosing of immunosuppressants has the potential to reduce complications and improve outcomes in renal transplantation. A comprehensive stratification model may facilitate proactive identification of renal transplant recipients at high risk for hypomagnesaemia. Standardizing data collection at transplant centres is essential to support research, generate strong evidence, and improve management of hypomagnesaemia in renal transplant recipients.

Hypomagnesaemia is a common but often overlooked issue in renal transplant patients, affecting long-term graft and patient outcomes. This review summarises current knowledge, notes diagnostic and treatment challenges, and highlights new approaches such as improved Mg measurement, pharmacogenomics, and microbiome research for more targeted hypomagnesaemia management.

In summary, the recommended clinical pathway includes monitoring ionised Mg, applying risk stratification and reviewing Mg supplementation

Author Contributions

M.E., A.A.A., M.Y.B., H.M. and P.A.B. conducted the literature review and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- al-Ghamdi, S.M.; Cameron, E.C.; Sutton, R.A. Magnesium deficiency: Pathophysiologic and clinical overview. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1994, 24, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaza Ortiz, C.; Fernández Fernández, C.; Pujol Pujol, M.; Muñiz Rincón, M.; Aiffil Meneses, A.S.; Pérez Flores, I.M.; Calvo Romero, N.; Moreno de la Higuera, M.Á.; Rodríguez Cubillo, B.; Ramos Corral, R.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Potential Protective Strategies for Hypomagnesemia in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laecke, S.; Van Biesen, W. Hypomagnesaemia in kidney transplantation. Transplant. Rev. 2015, 29, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Han, M.; Xue, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; Qi, H.; Wang, Y. Prediction models for acute kidney injury following liver transplantation: A systematic review and critical appraisal. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2025, 86, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratiu, I.A.; Moisa, C.; Marc, L.; Olariu, N.; Ratiu, C.A.; Bako, G.C.; Ratiu, A.; Fratila, S.; Teusdea, A.C.; Ganea, M.; et al. The Impact of Hypomagnesemia on the Long-Term Evolution After Kidney Transplantation. Nutrients 2024, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadi, F. Hypomagnesemia: An evidence-based approach to clinical cases. Iran. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 4, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, P.C.; Pham, P.M.; Pham, S.V.; Miller, J.M.; Pham, P.T. Hypomagnesemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billiauws, L.; Maggiori, L.; Joly, F.; Panis, Y. Medical and surgical management of short bowel syndrome. J. Visc. Surg. 2018, 155, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosanoff, A.; Costello, R.B.; Johnson, G.H. Effectively Prescribing Oral Magnesium Therapy for Hypertension: A Categorized Systematic Review of 49 Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, R.W.; Nishat, S.M.H.; Alzaabi, A.A.; Alzaabi, F.M.; Al Tarawneh, D.J.; Al Tarawneh, Y.J.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.A.M.; Siddiqui, T.W.; Siddiqui, S.W. The Connection Between Magnesium and Heart Health: Understanding Its Impact on Cardiovascular Wellness. Cureus 2024, 16, e72302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Blood and Transpant. Organ Transplant Waiting List Hits Record High as Donor and Transplant Numbers Fall. Available online: https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/get-involved/news/organ-transplant-waiting-list-hits-record-high-as-donor-and-transplant-numbers-fall/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Solhjoo, M.; Kumar, S.C. New Onset Diabetes After Transplant. (Updated 28 August 2023). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544220/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Van Laecke, S.; Desideri, F.; Geerts, A.; Van Vlierberghe, H.; Berrevoet, F.; Rogiers, X.; Troisi, R.; de Hemptinne, B.; Vanholder, R.; Colle, I. Hypomagnesemia and the risk of new-onset diabetes after liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2010, 16, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, A.S.; Duveau, A.; Planchais, M.; Subra, J.F.; Sayegh, J.; Augusto, J.F. Serum Magnesium after Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, M.M.; Elgohary, I.E.; Abouelnaga, S.F.; Elian, F.A.S.; Zeid, M.M. Hypomagnesemia and its association with calcineurin inhibitor use in renal transplant recipients. J. Egypt. Soc. Nephrol. Transplant. 2023, 23, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.-A.; Bruserud, Ø. Hypomagnesemia in critically ill patients. J. Intensive Care 2018, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santosh Raju, K.; BhaskaraRao, J.V.; Naidu, B.T.K.; Sunil Kumar, N. A Study of Hypomagnesemia in Patients Admitted to the ICU. Cureus 2023, 15, e41949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyckner, T.; Wester, P.O. Intracellular magnesium loss after diuretic administration. Drugs 1984, 28 (Suppl. S1), 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzen, R.; Davies, A.; Veenhuizen, M.; Campbell, M.; Pitt, S.J.; Ajjan, R.A.; Stewart, A.J. Magnesium Deficiency and Cardiometabolic Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagallo, M.; Dominguez, L.J. Magnesium and type 2 diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, J.F. British National Formulary 90; British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Elin, R.J. Assessment of magnesium status. Clin. Chem. 1987, 33, 1965–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Alawi, A.M.; Majoni, S.W.; Falhammar, H. Magnesium and Human Health: Perspectives and Research Directions. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 2018, 9041694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.T.; Soman, S.S.; Yee, J. Magnesium Balance and Measurement. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018, 25, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touyz, R.M. Magnesium in clinical medicine. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 1278–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalfenberg, G.K.; Genuis, S.J. The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare. Scientifica 2017, 2017, 4179326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaneri-Day, S.; Rosanoff, A. Clinical Guideline for Detection and Management of Magnesium Deficiency in Ambulatory Care. Nutrients 2025, 17, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Del Gobbo, L.C.; Rosanoff, A.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Song, Y. Effects of Magnesium Supplementation on Blood Pressure: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trials. Hypertension 2016, 68, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. J. Intern. Med. 2007, 262, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.Y.; Xun, P.; He, K.; Qin, L.Q. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 2116–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Hao, J.; Hu, H.; Hao, L. The level of serum albumin is associated with renal prognosis and renal function decline in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitliya, A.; Vasudevan, S.S.; Batra, V.; Patel, M.B.; Desai, A.; Nethagani, S.; Pitliya, A. Global prevalence of hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus—A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Endocrine 2024, 84, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topf, J.M.; Murray, P.T. Hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2003, 4, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, M.E.; Al-Siba’i, M.B.; Skooge, W.C. Clinical manifestations of hypomagnesemia. Crit. Care Med. 1986, 14, 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieboom, B.C.; Niemeijer, M.N.; Leening, M.J.; van den Berg, M.E.; Franco, O.H.; Deckers, J.W.; Hofman, A.; Zietse, R.; Stricker, B.H.; Hoorn, E.J. Serum Magnesium and the Risk of Death From Coronary Heart Disease and Sudden Cardiac Death. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Pan, C.; Fang, H.; Xu, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, J.; He, L.; Fang, M.; Chen, C. The role of serum magnesium in the prediction of Acute Kidney Injury after total aortic arch replacement: A Prospective Observational study. J. Med. Biochem. 2024, 43, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosner, M.H.; Ha, N.; Palmer, B.F.; Perazella, M.A. Acquired Disorders of Hypomagnesemia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2023, 98, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, M.; Tsalouchos, A. Microbiota, renal disease and renal transplantation. World J. Transplant. 2021, 11, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, A.C.; Clemens, K.K.; Sontrop, J.M.; Dixon, S.N.; Killin, L.; Anderson, S.; Acedillo, R.R.; Bagga, A.; Bohm, C.; Brown, P.A.; et al. Magnesium and Fracture Risk in the General Population and Patients Receiving Dialysis: A Narrative Review. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2023, 10, 20543581231154183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, P.J.; Ávila, G.; Domingos, D.; Gil, C.; Ferreira, A. Lower serum magnesium levels are associated with a higher risk of fractures and vascular calcifications in hemodialysis patients. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 18, sfae381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, A.E.; Sarlo, G.L.; Holton, K.F. The Role of Magnesium in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2018, 10, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Akimbekov, N.S.; Grant, W.B.; Dean, C.; Fang, X.; Razzaque, M.S. Neuroprotective effects of magnesium: Implications for neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1406455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S.; Kumar, S.; Hussain, A.; Mishra, N.; Garg, A.; Gowda, B.H.J.; Farid, A.; Gupta, G.; Dua, K.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. A narrative review on the role of magnesium in immune regulation, inflammation, infectious diseases, and cancer. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.d.S.; Santos, M.Q.d.; Makiyama, E.N.; Hoffmann, C.; Fock, R.A. The essential role of magnesium in immunity and gut health: Impacts of dietary magnesium restriction on peritoneal cells and intestinal microbiome. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2025, 88, 127604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.C.; Ng, C.M.; Barrett, J.S.; Luo, A.J.; Zhang, B.K.; Deng, C.H.; Xi, L.Y.; Cheng, K.; Ming, Y.Z.; Yang, G.P.; et al. Effects of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 polymorphisms on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics in Chinese adult renal transplant recipients: A population pharmacokinetic analysis. Pharmacogenetics Genom. 2013, 23, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannachi, I.; Ben Fredj, N.; Chadli, Z.; Ben Fadhel, N.; Ben Romdhane, H.; Touitou, Y.; Boughattas, N.A.; Chaabane, A.; Aouam, K. Effect of CYP3A4*22 and CYP3A4*1B but not CYP3A5*3 polymorphisms on tacrolimus pharmacokinetic model in Tunisian kidney transplant. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 396, 115000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xajil-Ramos, L.Y.; Gándara-Mireles, J.A.; Vargas Rosales, R.J.; Sánchez García, O.K.; Ruano Toledo, A.M.; Aldana de la Cruz, A.K.; Lares-Asseff, I.; Patrón-Romero, L.; Almanza-Reyes, H.; Lou-Meda, R. Impact of CYP3A5 1* and 3* single nucleotide variants on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics and graft rejection risk in pediatric kidney transplant patients. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1592134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiske, B.L.; Zeier, M.G.; Craig, J.C.; Ekberg, H.; Garvey, C.A.; Green, M.D.; Jha, V.; Josephson, M.A.; Kiberd, B.A.; Kreis, H.A.; et al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9 (Suppl. S3), S1–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touyz, R.M.; de Baaij, J.H.F.; Hoenderop, J.G.J. Magnesium Disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1998–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; Liu, J.; O’Keefe, J.H. Magnesium for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Open Heart 2018, 5, e000775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janett, S.; Camozzi, P.; Peeters, G.G.; Lava, S.A.; Simonetti, G.D.; Goeggel Simonetti, B.; Bianchetti, M.G.; Milani, G.P. Hypomagnesemia Induced by Long-Term Treatment with Proton-Pump Inhibitors. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 951768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilli, E.; Khadge, S.; Fabiano, A.; Zambito, Y.; Williams, T.; Tarantino, G. Magnesium bioavailability after administration of sucrosomial® magnesium: Results of an ex-vivo study and a comparative, double-blinded, cross-over study in healthy subjects. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, L.F.; Alessi, M.; Bertoldi, G.; Rossato, V.; Di Vico, V.; Nalesso, F.; Calò, L.A. Calcineurin-Inhibitor-Induced Hypomagnesemia in Kidney Transplant Patients: A Monocentric Comparative Study between Sucrosomial Magnesium and Magnesium Pidolate Supplementation. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).