Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Patient Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Health Literacy in Chronic Kidney Disease

3. Benefits of Patient Education in Chronic Kidney Disease

Patient Education for Unplanned Dialysis

4. Patient Perception of Education in Chronic Kidney Disease

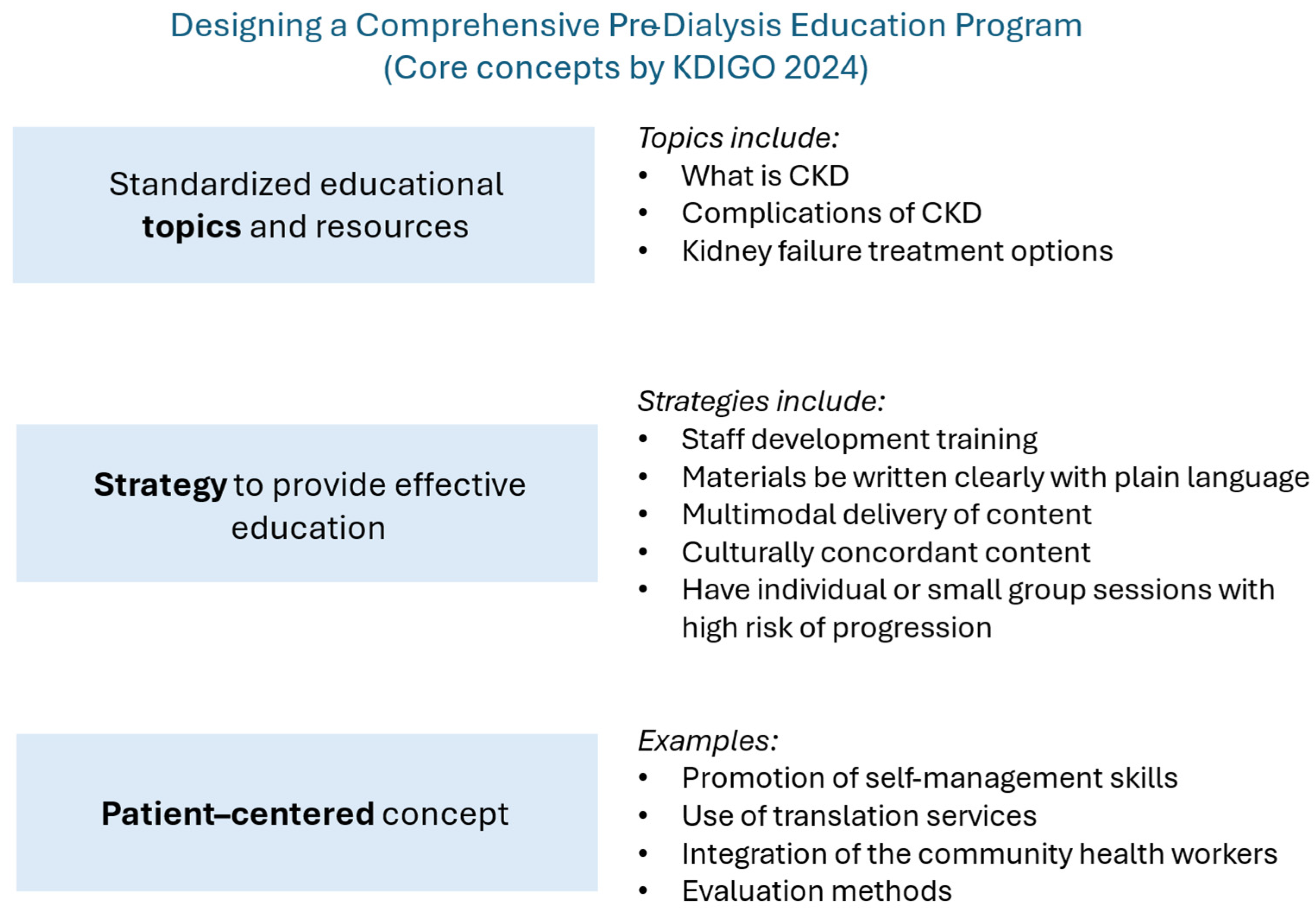

5. Ideal Education Programs for Chronic Kidney Disease

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CKM | Conservative kidney management |

| ESKD | End-stage kidney disease |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| KDOQI | Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative |

| KFRE | Kidney failure risk equation |

| KPNW | Kaiser Permanente North West |

| KRT | Kidney replacement therapy |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| PDAs | Patient decision aids |

| TCUs | Transitional care units |

| TIDieR | Template for Intervention Description and Replication |

References

- Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G.; Levin, A.; Ye, F.; Saad, S.; Zaidi, D.; Houston, G.; Damster, S.; Arruebo, S.; Abu-Alfa, A.; et al. ISN–Global Kidney Health Atlas: A Report by the International Society of Nephrology: An Assessment of Global Kidney Health Care Status Focussing on Capacity, Availability, Accessibility, Affordability and Outcomes of Kidney Disease; International Society of Nephrology: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: An international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2023; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar]

- Tangri, N.; Stevens, L.A.; Griffith, J.; Tighiouart, H.; Djurdjev, O.; Naimark, D.; Levin, A.; Levey, A.S. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 2011, 305, 1553–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grams, M.E.; Brunskill, N.J.; Ballew, S.H.; Sang, Y.; Coresh, J.; Matsushita, K.; Surapaneni, A.; Bell, S.; Carrero, J.J.; Chodick, G.; et al. The Kidney Failure Risk Equation: Evaluation of Novel Input Variables including eGFR Estimated Using the CKD-EPI 2021 Equation in 59 Cohorts. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 34, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, R.W.; Shepherd, D.; Medcalf, J.F.; Xu, G.; Gray, L.J.; Brunskill, N.J. The Kidney Failure Risk Equation for prediction of end stage renal disease in UK primary care: An external validation and clinical impact projection cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangri, N.; Grams, M.E.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Appel, L.J.; Astor, B.C.; Chodick, G.; Collins, A.J.; Djurdjev, O.; Elley, C.R.; et al. Multinational Assessment of Accuracy of Equations for Predicting Risk of Kidney Failure: A Meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 315, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, E.B.; Yang, X.; Thorp, M.L.; Arnold, B.M.; Tabano, D.C.; Petrik, A.F.; Smith, D.H.; Platt, R.W.; Johnson, E.S. Predicting 5-Year Risk of RRT in Stage 3 or 4 CKD: Development and External Validation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landray, M.J.; Thambyrajah, J.; McGlynn, F.J.; Jones, H.J.; Baigent, C.; Kendall, M.J.; Townend, J.N.; Wheeler, D.C. Epidemiological evaluation of known and suspected cardiovascular risk factors in chronic renal impairment. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2001, 38, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, H.U.; Altenbuchinger, M.; Schultheiss, U.T.; Raffler, J.; Kotsis, F.; Ghasemi, S.; Ali, I.; Kollerits, B.; Metzger, M.; Steinbrenner, I.; et al. A Predictive Model for Progression of CKD to Kidney Failure Based on Routine Laboratory Tests. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 79, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narva, A.S.; Norton, J.M.; Boulware, L.E. Educating Patients about CKD: The Path to Self-Management and Patient-Centered Care. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.; Khunti, K.; Stone, M.; Farooqi, A.; Carr, S. Educational interventions in kidney disease care: A systematic review of randomized trials. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008, 51, 933–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Vargas, P.A.; Tong, A.; Howell, M.; Craig, J.C. Educational Interventions for Patients with CKD: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binik, Y.M.; Devins, G.M.; Barre, P.E.; Guttmann, R.D.; Hollomby, D.J.; Mandin, H.; Paul, L.C.; Hons, R.B.; Burgess, E.D. Live and learn: Patient education delays the need to initiate renal replacement therapy in end-stage renal disease. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1993, 181, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devins, G.M.; Mendelssohn, D.C.; Barre, P.E.; Binik, Y.M. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention and coping styles influence time to dialysis in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 42, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manns, B.J.; Taub, K.; Vanderstraeten, C.; Jones, H.; Mills, C.; Visser, M.; McLaughlin, K. The impact of education on chronic kidney disease patients’ plans to initiate dialysis with self-care dialysis: A randomized trial. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, 1777–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devins, G.M.; Mendelssohn, D.C.; Barre, P.E.; Taub, K.; Binik, Y.M. Predialysis psychoeducational intervention extends survival in CKD: A 20-year follow-up. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 46, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.J.; Garg, A.X.; Goeree, R.; Levin, A.; Molzahn, A.; Rigatto, C.; Singer, J.; Soltys, G.; Soroka, S.; Ayers, D.; et al. A nurse-coordinated model of care versus usual care for stage 3/4 chronic kidney disease in the community: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Tsai, Y.F.; Sun, C.Y.; Wu, I.W.; Lee, C.C.; Wu, M.S. The impact of self-management support on the progression of chronic kidney disease—A prospective randomized controlled trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2011, 26, 3560–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zuilen, A.D.; Bots, M.L.; Dulger, A.; van der Tweel, I.; van Buren, M.; Ten Dam, M.A.; Kaasjager, K.A.; Ligtenberg, G.; Sijpkens, Y.W.; Sluiter, H.E.; et al. Multifactorial intervention with nurse practitioners does not change cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012, 82, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.L.; Yen, M.; Fetzer, S.; Sung, J.M.; Hung, S.Y. Effects of targeted interventions on lifestyle modifications of chronic kidney disease patients: Randomized controlled trial. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2013, 35, 1107–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, K.L.; Wingard, R.L.; Hakim, R.M.; Eden, S.; Shintani, A.; Wallston, K.A.; Huizinga, M.M.; Elasy, T.A.; Rothman, R.L.; Ikizler, T.A. Low health literacy associates with increased mortality in ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1979–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skelton, S.L.; Waterman, A.D.; Davis, L.A.; Peipert, J.D.; Fish, A.F. Applying best practices to designing patient education for patients with end-stage renal disease pursuing kidney transplant. Prog. Transpl. 2015, 25, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribitsch, W.; Haditsch, B.; Otto, R.; Schilcher, G.; Quehenberger, F.; Roob, J.M.; Rosenkranz, A.R. Effects of a pre-dialysis patient education program on the relative frequencies of dialysis modalities. Perit. Dial. Int. 2013, 33, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo, A.C.; Yang, W.; Lora, C.M.; Gordon, E.J.; Diamantidis, C.J.; Ford, V.; Kusek, J.W.; Lopez, A.; Lustigova, E.; Nessel, L.; et al. Limited health literacy is associated with low glomerular filtration in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Clin. Nephrol. 2014, 81, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch-Weser, S.; Porteny, T.; Rifkin, D.E.; Isakova, T.; Gordon, E.J.; Rossi, A.; Baumblatt, G.L.; St Clair Russell, J.; Damron, K.C.; Wofford, S.; et al. Patient Education for Kidney Failure Treatment: A Mixed-Methods Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 78, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, R.W.; Stel, V.S.; Rahmel, A.; Murphy, M.; Vanholder, R.C.; Massy, Z.A.; Jager, K.J. Patient-reported factors influencing the choice of their kidney replacement treatment modality. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2022, 37, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, R.W.; Jager, K.J.; Vanholder, R.C.; Couchoud, C.; Murphy, M.; Rahmel, A.; Massy, Z.A.; Stel, V.S. Results of the European EDITH nephrologist survey on factors influencing treatment modality choice for end-stage kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2021, 37, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Luijtgaarden, M.W.; Jager, K.J.; Segelmark, M.; Pascual, J.; Collart, F.; Hemke, A.C.; Remon, C.; Metcalfe, W.; Miguel, A.; Kramar, R.; et al. Trends in dialysis modality choice and related patient survival in the ERA-EDTA Registry over a 20-year period. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2016, 31, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Park, J.Y.; Kang, S.; Kim, K.H.; Ryu, D.R.; Kim, H.; Joo, K.W.; Lim, C.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, D.K. Dialysis Modality and Mortality in the Elderly: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, T.J.; Joosten, H.; van Buren, M.; Vinen, K.; Brown, E.A. A review of supportive care for older people with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Is Health Literacy? October 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Health Literacy. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-literacy (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. Health Literacy. 6 February 2025. Available online: https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/health-literacy (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, 3rd Edition. March 2024. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/intro.html (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Campbell, Z.C.; Dawson, J.K.; Kirkendall, S.M.; McCaffery, K.J.; Jansen, J.; Campbell, K.L.; Lee, V.W.; Webster, A.C. Interventions for improving health literacy in people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 12, CD012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langham, R.G.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Bonner, A.; Balducci, A.; Hsiao, L.L.; Kumaraswami, L.A.; Laffin, P.; Liakopoulos, V.; Saadi, G.; Tantisattamo, E.; et al. Kidney Health for All: Bridging the Gap in Kidney Health Education and Literacy. Am. J. Hypertens. 2022, 35, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.M.; Fraser, S.; Dudley, C.; Oniscu, G.C.; Tomson, C.; Ravanan, R.; Roderick, P. Health literacy and patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2018, 33, 1545–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutner, M.; Greenburg, E.; Jin, Y.; Paulsen, C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy; NCES 2006-483; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, D.; Green, J.A. Health literacy in kidney disease: Review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. World J. Nephrol. 2016, 5, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.M.; Bradley, J.A.; Bradley, C.; Draper, H.; Johnson, R.; Metcalfe, W.; Oniscu, G.; Robb, M.; Tomson, C.; Watson, C. Limited health literacy in advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, M.-A.; Carpenter, L.; Dolan, H.; Bravo, P.; Mann, M.; Bunn, F.; Elwyn, G. Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, M.D.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Foitzik, E.M.; Westerhuis, R.; Navis, G.; de Winter, A.F. How to tackle health literacy problems in chronic kidney disease patients? A systematic review to identify promising intervention targets and strategies. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 36, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toapanta, N.; Salas-Gama, K.; Pantoja, P.E.; Soler, M.J. The role of low health literacy in shared treatment decision-making in patients with kidney failure. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16 (Suppl. S1), i4–i11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.W.; Parker, R.M.; Williams, M.V.; Pitkin, K.; Parikh, N.S.; Coates, W.; Imara, M. The health care experience of patients with low literacy. Arch. Fam. Med. 1996, 5, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morony, S.; Flynn, M.; McCaffery, K.J.; Jansen, J.; Webster, A.C. Readability of Written Materials for CKD Patients: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 65, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Martinez, J.; Kallus, L.; Levine, H.M.; Lavernia, F.; Pierre, A.J.; Mancilla, J.; Barthe, A.; Duran, C.; Kotzker, W.; Wagner, E.; et al. Community-Engaged Research (CEnR) to Address Gaps in Chronic Kidney Disease Education among Underserved Latines—The CARE Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Martinez, J.; Delgado-Enciso, I.; Duran, C.; Kallus, L.; Jean-Pierre, A.; Lopez, B.; Mancilla, J.; Madruga, Y.; Hernandez-Fuentes, G.A.; Kotzker, W.; et al. Patients’ Perspectives on the Acceptability and Effectiveness of a Community Health Worker-Led Intervention to Increase Chronic Kidney Disease Knowledge and Screening among Underserved Latine Adults: The CARE 2.0 Study. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novick, T.K.; Diaz, S.; Barrios, F.; Cubas, D.; Choudhary, K.; Nader, P.; ElKhoury, R.; Cervantes, L.; Jacobs, E.A. Perspectives on Kidney Disease Education and Recommendations for Improvement Among Latinx Patients Receiving Emergency-Only Hemodialysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2124658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes-Barreto, J.G.; Silva, M.I.B.; Qureshi, A.R.; Bregman, R.; Cervante, V.F.; Carrero, J.J.; Avesani, C.M. Can renal nutrition education improve adherence to a low-protein diet in patients with stages 3 to 5 chronic kidney disease? J. Ren. Nutr. 2013, 23, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.M.; Cerulli, J.; Grabe, D.W.; Fox, C.; Vassalotti, J.A.; Prokopienko, A.J.; Pai, A.B. NSAID-avoidance education in community pharmacies for patients at high risk for acute kidney injury, upstate New York, 2011. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E220. [Google Scholar]

- Wright-Nunes, J.A.; Luther, J.M.; Ikizler, T.A.; Cavanaugh, K.L. Patient knowledge of blood pressure target is associated with improved blood pressure control in chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 88, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.J.; Nakonechnyi, A.; Phan, T.; Moore, C.; Drury, E.; Grewal, R.; Liebman, S.E.; Levy, D.; Saeed, F. Exploring Patient Needs and Preferences in CKD Education: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Kidney360 2024, 5, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodage, H.M.H.; McGuire, A.; Seib, C.; Bonner, A. Effectiveness of teach-back for chronic kidney disease patient education: A systematic review. J. Ren. Care 2024, 50, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-L.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Yang, C.-W.; Hsu, M.-F.; Chung, Y.-C. Effects of a Health Literacy Education Program on Mental Health and Renal Function in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nurs. Res. 2024, 32, e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowska, A.; Alscher, M.D.; Vanga, S.R.; Koch, M.; Aarup, M.; Qureshi, A.R.; Lindholm, B.; Rutherford, P. Offering Patients Therapy Options in Unplanned Start (OPTiONS): Implementation of an educational program is feasible and effective. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, B.T. Transitional Care Units: Greater Than the Sum of Their Parts. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morfin, J.A.; Yang, A.; Wang, E.; Schiller, B. Transitional dialysis care units: A new approach to increase home dialysis modality uptake and patient outcomes. Semin. Dial. 2018, 31, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combes, G.; Sein, K.; Allen, K. How does pre-dialysis education need to change? Findings from a qualitative study with staff and patients. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenship, D.M.; Usvyat, L.; Kraus, M.A.; Chatoth, D.K.; Lasky, R.; Turk, J.E., Jr.; Maddux, F.W. Assessing the impact of transitional care units on dialysis patient outcomes: A multicenter, propensity score-matched analysis. Hemodial. Int. 2023, 27, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.; Hussain, S.; Thomas, N. Innovative education for people with chronic kidney disease: An evaluation study. J. Ren. Care 2020, 46, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knicely, D.H.; Rinaldi, K.; Snow, S.; Cervantes, C.E.; Choi, M.J.; Jaar, B.G.; Thavarajah, S. The ABCs of Kidney Disease: Knowledge Retention and Healthcare Involvement. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 23743735211065285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, R.; Marsh, D.; Vonesh, E.; Peters, V.; Nissenson, A. Patient education and access of ESRD patients to renal replacement therapies beyond in-center hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Biesen, W.; van der Veer, S.N.; Murphey, M.; Loblova, O.; Davies, S. Patients’ perceptions of information and education for renal replacement therapy: An independent survey by the European Kidney Patients’ Federation on information and support on renal replacement therapy. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dipten, C.; De Grauw, W.J.; Wetzels, J.F.; Assendelft, W.J.; Scherpbier-de Haan, N.D.; Dees, M.K. What patients with mild-to-moderate kidney disease know, think, and feel about their disease: An in-depth interview study. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2018, 31, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, G.; Bischof, A.; Rumpf, H.J. Motivational Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Approach for Use in Medical Practice. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, M.D.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Westerhuis, R.; Tullius, J.M.; Vervoort, J.P.M.; Navis, G.; de Winter, A.F. A longitudinal qualitative study to explore and optimize self-management in mild to end stage chronic kidney disease patients with limited health literacy: Perspectives of patients and health care professionals. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.K.; Dixon, A.; Trevena, L.; Nutbeam, D.; McCaffery, K.J. Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowels, M. Andragogy in Action: Applying Modern Principles of Adult Education; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, A.; Tirabassi, J.; Doyle, M. Scenario-Based Discussion: Using Adult Learning Theory to Improve Discussion on Lifestyle Medicine for Healthy Adults. Ann. Fam. Med. 2024, 22, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.M.; Cooknell, L.E. The Power of 3: Using adult learning principles to facilitate patient education. Nursing 2017, 47, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantar, L.D.; Ezzeddine, S.; Rizk, U. Rethinking clinical instruction through the zone of proximal development. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 95, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, F.; Jonker, G.; Rinia, M.; Ten Cate, O.; Hoff, R.G. Simulation at the Frontier of the Zone of Proximal Development: A Test in Acute Care for Inexperienced Learners. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhalalati, B.A.; Taylor, A. Adult Learning Theories in Context: A Quick Guide for Healthcare Professional Educators. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2019, 6, 2382120519840332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnard Bagnis, C.; Crepaldi, C.; Dean, J.; Goovaerts, T.; Melander, S.; Nilsson, E.L.; Prieto-Velasco, M.; Trujillo, C.; Zambon, R.; Mooney, A. Quality standards for predialysis education: Results from a consensus conference. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2015, 30, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.M.; Cavanaugh, K.L.; Jia, H.; Hale-Gallardo, J.; Wadhwa, A.; Fischer, M.J.; Reule, S.; Palevsky, P.M.; Fried, L.F.; Crowley, S.T. Needs and Considerations for Standardization of Kidney Disease Education in Patients with Advanced CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2023, 18, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A.M.; Hale-Gallardo, J.; Orozco, T.; Freytes, I.; Purvis, Z.; Romero, S.; Jia, H. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate and assess the effect of comprehensive pre-end stage kidney disease education on home dialysis use in veterans, rationale and design. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eck van der Sluijs, A.; Vonk, S.; van Jaarsveld, B.C.; Bonenkamp, A.A.; Abrahams, A.C. Good practices for dialysis education, treatment, and eHealth: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.T.; Blankestijn, P.J.; Dember, L.M.; Gallieni, M.; Harris, D.C.H.; Lok, C.E.; Mehrotra, R.; Stevens, P.E.; Wang, A.Y.; Cheung, M.; et al. Dialysis initiation, modality choice, access, and prescription: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanachayanont, T.; Chanpitakkul, M.; Hengtrakulvenit, J.; Watcharakanon, P.; Wisansak, W.; Tancharoensukjit, T.; Kaewsringam, P.; Leesmidt, V.; Pongpirul, K.; Lekagul, S.; et al. Effectiveness of integrated care on delaying chronic kidney disease progression in rural communities of Thailand (ESCORT-2) trials. Nephrology 2021, 26, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, S.D.; Bansal, N.; Cavanaugh, K.L.; Chang, A.; Crowley, S.; Delgado, C.; Estrella, M.M.; Ghossein, C.; Ikizler, T.A.; Koncicki, H.; et al. KDOQI US Commentary on the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2025, 85, 135–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, R.L.; Howard, K.; Webster, A.C.; Snelling, P. Patient INformation about Options for Treatment (PINOT): A prospective national study of information given to incident CKD Stage 5 patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2011, 26, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutilli, C.C. Excellence in Patient Education: Evidence-Based Education that “Sticks” and Improves Patient Outcomes. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 55, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.W.; Wong, J.V.; Auguste, B.L.; Logan, A.G.; Nolan, R.P.; Chan, C.T. Design and Development of a Digital Counseling Program for Chronic Kidney Disease. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2022, 9, 20543581221103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuot, D.S.; Davis, E.; Velasquez, A.; Banerjee, T.; Powe, N.R. Assessment of printed patient-educational materials for chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2013, 38, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.C.; Alba, R.; Krisanapan, P.; Acharya, C.M.; Suppadungsuk, S.; Csongradi, E.; Mao, M.A.; Craici, I.M.; Miao, J.; Thongprayoon, C.; et al. AI-Driven Patient Education in Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluating Chatbot Responses against Clinical Guidelines. Diseases 2024, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easom, A.M.; Shukla, A.M.; Rotaru, D.; Ounpraseuth, S.; Shah, S.V.; Arthur, J.M.; Singh, M. Home run—Results of a chronic kidney disease Telemedicine Patient Education Study. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 13, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, E.J.; Lash, J.P. A timely change in CKD delivery: Promoting patient education. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 57, 375–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Benefits of Chronic Kidney Disease Education |

| Enhance Patient Understanding |

| • Make informed decisions |

| • Knowledge retention |

| • Improved mental health and self-management behaviors |

| • Autonomy with self-care dialysis modalities |

| Improved Health Outcomes |

| • Adhere to treatment plans |

| • Reduce complications |

| • Lower infection risks (vascular access planning) |

| • Decrease cardiovascular risks by better blood pressure control |

| Delay Kidney Disease progression |

| • Knowledge of dietary modifications |

| • Medication adherence |

| • Risk factor management |

| Reduced Healthcare Costs |

| • Prevention of complications |

| • Knowledge of all treatments including conservative kidney management |

| Promote Home Kidney Replacement Modalities |

| • Promote patient autonomy |

| Increase Rate of Kidney Transplant |

| • Early referrals for transplant evaluation |

| • Pre-emptive transplant candidacy |

| • Early identification of possible living donors |

| Patient Perception of CKD Education | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Population | Results | Key Themes |

| Exploring patient needs and preferences (Allen et al., 2024 [55]) | Cross-sectional survey of CKD patients 21 years and older (N = 337) |

| Comprehensive education about CKD Integration of digital content |

| A longitudinal qualitative study to explore and optimize self-management in mild to end stage chronic kidney disease with limited health literacy (Boonstra et al., 2022 [69]) | Semi-structured in-depth reviews and focus groups of CKD patients (N = 24) |

| Optimization of self-management by early education and applying patient-centered strategies |

| What Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Kidney Disease Know, Think, and Feel about their disease (Van Dipten et al., 2018 [67]) | Patients with mild-moderate kidney disease (N = 25) |

| Comprehensive education about CKD Empathy, emotional support Tailoring education to patient’s needs |

| How does pre-dialysis education need to change? (Combes et al., 2017 [61]) | Qualitative study, 4 hospitals, 96 staff and 93 dialysis patients |

| Elimination of bias Staff training Call for ongoing KRT education and review of treatment choices Emotional support |

| Patients’ perceptions of information and education for RRT (Van Biesen et al., 2014 [66]) | 36 countries (N = 3867) patients on hemodialysis (in-center) or had a functioning graft |

| Call to eliminate bias in KRT modalities Improvement in the perception of the patients to choose an alternative modality |

| Patient education and access of ESRD patients to RRT beyond in-center hemodialysis (Mehrotra et al., 2005 [65]) | 299 dialysis units (N = 1365) |

| Incomplete presentation of treatment options |

| Components for a Successful Pre-Dialysis Education Program |

|---|

| • Promotion of self-management skills |

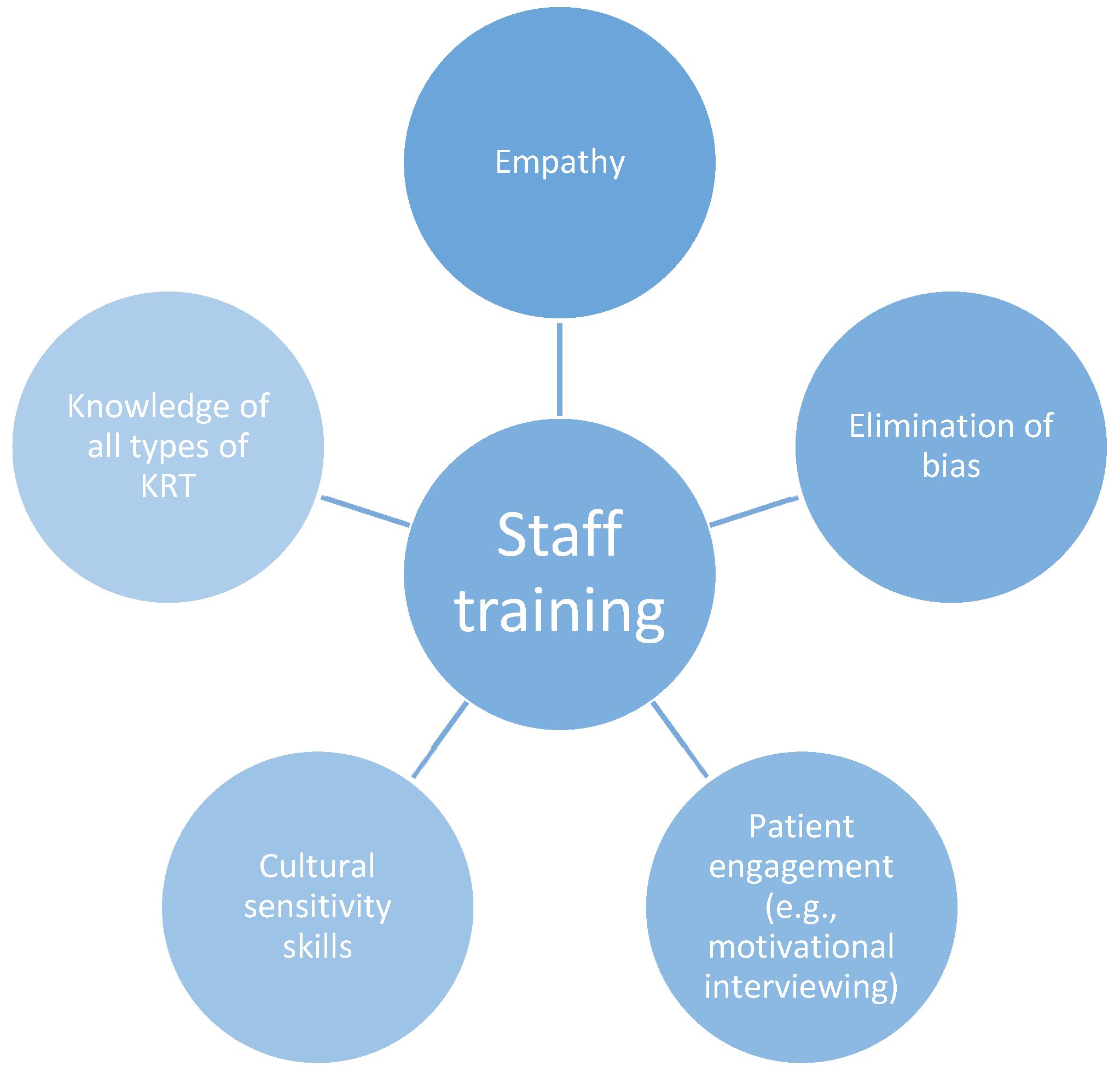

| • Staff training to eliminate bias |

| • Respect for cultural context |

| • Employment of teach-back method |

| • Translational services/Translated materials |

| • Standardization of program |

| • Multimodal education materials |

| • Multidisciplinary team involvement |

| • Ongoing KRT education |

| • Health literacy training for educators/providers |

| • Quality assessment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faldu, C.T.; Knicely, D.H. Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Patient Education. Kidney Dial. 2025, 5, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030032

Faldu CT, Knicely DH. Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Patient Education. Kidney and Dialysis. 2025; 5(3):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030032

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaldu, Czarina T., and Daphne H. Knicely. 2025. "Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Patient Education" Kidney and Dialysis 5, no. 3: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030032

APA StyleFaldu, C. T., & Knicely, D. H. (2025). Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and Patient Education. Kidney and Dialysis, 5(3), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/kidneydial5030032