1. Introduction

Unexpected economic circumstances and expense shocks often lead to financial stress, especially within marginalized communities [

1]. Interest in financial stress has intensified given the prevalence of financial insecurity and financial fragility among low-income and minority communities since the Great Recession and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic [

2,

3]. These economic pressures and financial stresses have been building, with one in four Americans described as economically vulnerable [

4] and only 27 percent of low-income individuals having sufficient savings to cover three months of expenses [

5]. Yet, the COVID-19 pandemic further upended daily life for many households.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many struggling families fell behind on basic needs and accumulated higher levels of debt [

6]. Low-income families of color were not only more likely to struggle to pay for their housing [

7], but they were also most affected by pandemic-related economic displacement, including job loss and income reductions [

8]. Beyond income, savings was also impacted among lower and middle-income households and households of color as they were forced to seek immediate liquidity solutions by borrowing from savings or increasing credit card debt [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Added to that, low-income households entered the pandemic with limited savings and less discretionary income for necessities [

13].

The extant literature demonstrates that economically vulnerable families seek to mitigate financial stress and difficulties by employing formal (e.g., increased work effort, loans, credit cards, payday loans, pawnshops) and informal (e.g., borrowing from family and friends, seeking support from community agencies) financial coping strategies [

14,

15,

16]. Consistent research finds that economically vulnerable individuals facing financial stressors and those with limited or no access to mainstream banking services consider alternative financial services (AFS) a viable solution [

17]; however, habitual use of AFS traps consumers in cycles of debt and exacerbates their already fragile finances [

14]. AFS consist of financial services provided by actors outside of traditional banking institutions such as check-cashing services, payday lenders, and pawnshops [

1].

Prior research indicates that low-income and minority households disproportionately rely on AFS during economic downturns yet the role of demographic and attitudinal factors post-COVID remain underexplained [

17,

18]. This study uses the ABC-X Model of Family Stress and Coping [

19] to examine COVID-19 economic displacement factors associated with AFS use. Specifically, this research study examines how COVID-19 economic displacement factors, prior AFS use, and sociodemographic and attitudinal factors influence AFS use, using data from the nationally representative, cross-sectional 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey. This research is timely considering the lingering economic and social effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed and exacerbated financial vulnerabilities across U.S. households. A deeper understanding of how individuals cope with financial instability, formally and informally, is needed. The results of this study contribute to the field by examining a diverse set of responses to financial crisis, adding depth to the understanding of financial coping literature and offering a novel theoretical lens, using the ABC-X model, to better understand how stressors, resources, and perceptions shape financial behavior.

3. Materials and Methods

This study utilizes data from the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS), a web-based, nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of US adults conducted between April and August 2021 [

46]. The 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) was designed “to collect high-quality national survey data with large and generalizable samples of racial and ethnic groups in the United States” [

46]. The 2020 CMPS was offered in multiple languages in addition to English and Spanish. The CMPS questionnaire queried perceptions, experiences, as well as political and social attitudes across many facets of American life, including attitudes about the 2020 election and candidates, experiences with racism, policy attitudes, immigration, and personal experiences with civic engagement. Data were weighted within each racial group to fall within the margin of error of the adult population in the 2019 Census ACS 1-year data file for age, gender, education, nativity, and ancestry. A post-stratification ranking algorithm was used to balance each category within ±2% of the ACS estimates resulting in four ethno-racial groups for the dataset: non-Latino White, Black, Latino, and Asian/Pacific Islander. The 2020 CMPS dataset also consists of appended tract-level demographic data for each respondent. For this study, we utilize the non-oversampled, appended contextual dataset (

n = 14,977), to ascertain the impact of COVID-19 economic displacement, ethno-racial identity, and socioeconomic status on AFS use as a means to mitigate precarity.

3.1. Measures

Dependent variables: The study examines four dependent variables used to gauge self-reported likelihood of using AFS support mechanisms, assessed using the item, “How likely would you be to use each of the following types of financial support to help you address an unexpected income shortfall or other financial emergency?” The four types serve as the dependent variables: Credit Cards, Payday Loans, Public Benefits (such as unemployment insurance, food stamps), and Family and Friends. Responses to each question are measured on a 5 pt. Likert scale from (1) “very unlikely” to (5) “very likely”. We treat the dependent variables as linear responses. This operationalization captures a complete picture of how individuals respond to economic strain. Among these four dependent variables examined, payday loans serve as the primary proxy for AFSs.

Independent Variables: To examine the confluence of factors influencing the likelihood of utilizing AFSs, we leverage multiple measures from the 2020 CMPS. The study categorizes these factors into four blocks for ease of interpretation.

Measures in Block A capture four experiential factors: (1) personal COVID-related employment changes using nine questions (COVID Economic Displacement), with ‘yes’ = 1 and ‘no’ = 0; (2) recent experience with six types of debt (Debt Experience), with ‘yes’ = 1 and ‘no’ = 0; (3) prior experience with four forms of AFSs (i.e., check-cashing store, payday lending store or cash advance service, pawnshop, and title loan (Prior AFS Experience), with ‘yes’ = 1 and ‘no’ = 0; and (4) possession of a bank account (Bank Account), where ‘yes’ = 1.

Measures in Block B capture three attitudinal factors. The first two measures capture a respondent’s prospective thinking about the economy after a prompt triggering retrospective evaluations: (1) hopefulness about the “state of the national economy” (National Economy); and (2) hopefulness about one’s “personal economic being” (Personal Economic Being). The third measure captures a respondent’s trust in banks (Bank Trust). Higher numbers denote a greater degree of hopefulness and a higher level of trust, respectively.

Measures in Block C reflect two socio-geographic factors which often influence personal economic decisions: (1) perceived type of community lived in (Community), with locations defined in a categorical fashion to differentiate large urban area from rural areas, and (2) a measure of the income inequality (or the dispersion of income) in a respondent’s census tract based on the 2020 5-year estimates of the American Community Survey (Gini Index), with values between 0 and 1, where the former represents perfect equality between tract residents and where the latter represents perfect inequality between tract residents.

Measures in Block D are respondent demographics and thus captures covariates which have been found to affect household financial decisions: age; female (yes = 1), education level (Education, ‘grade less than 8’ = 1 … ‘postgraduate’ = 7); household income level (Income, ‘less than $20k’ = 1 … ‘$200k or more’ = 12); race/ethnic identity (White, Black, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander); marital status (Married, ‘yes’ = 1); party affiliation (Party, ‘Republican’ = 1, ‘Independent/Other’ = 2, ‘Democrat’ = 3); political conservatism (Ideology, ‘very liberal’ = 1 … ‘very conservative’ = 5); whether born in the US (US Born, ‘yes’ = 1); and, voter registration status (Registered, ‘yes’ = 1).

3.2. Analysis

We employ Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models to estimate the effects of the independent variables on the likelihood of using AFSs. OLS regression is a statistical method used to estimate the relationships between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables [

47]. It assumes linear relationships and minimizes the sum of the squared differences between observed and predicted values, allowing for the identification of significant predictors and their relative strength. We also examined the contextual, experiential, sociodemographic, and attitudinal factors shaping the use of AFSs during the early onset of COVID. To properly account for the complex survey design of the data, we utilize the

svyset command in Stata 18.0 to estimate all regression equations.

4. Results

This section discusses the statistical analysis, results (using OLS regression), hypothesis testing, and the interpretation of the results within the context of the ABC-X model. Results are presented in the following sequence. We begin in

Table 1 by presenting the descriptive statistics, including age, gender, political affiliation, political ideology, ethno-racial identity, and voter registration status. Among the unweighted population in this study, 20% (

n = 3000) were White, 27% (

n= 3970) were Black, 26% (

n = 3951) were Latino, and 27% (

n = 3973) were Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI). On average, respondents reported having some college or more. We also report means for the dependent variables. Of note, we only used the CMPS primary sample.

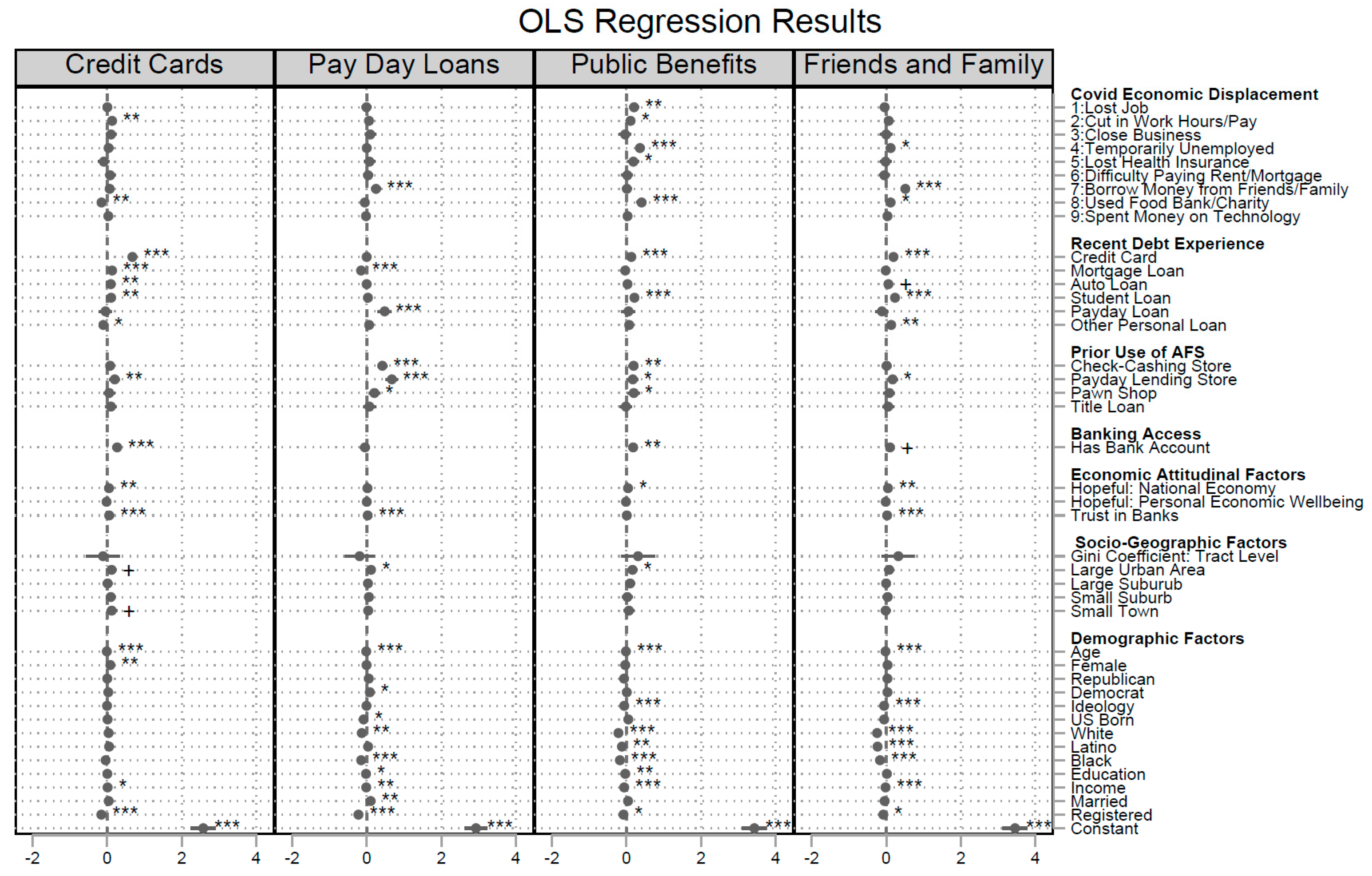

Next, we present the OLS coefficients derived from the four linear regression models in

Table 2. The results in

Table 2 showcase the varied impact of experiencing various aspects of COVID-19 economic displacement, economic attitudes, geographic location, and personal demographics on respondents’ answers about their likelihood of utilizing credit cards, payday loans, public benefits, or friends and family in response to an unexpected income shortfall or other financial emergency. We then address how the results compare to our hypotheses. Next, we leverage the OLS estimates in

Table 2 to estimate the sample’s overall predicted value on each of the dependent variables when respondents are modeled to have experienced one of the nine COVID-19 economic displacement items while the other independent variables are held constant at their mean. So, for instance, we derive a result of 3.5 when estimating the sample’s overall predicted value on the dependent variable Credit Cards when all respondents are changed to report having experienced a ‘loss of their job’ (a value of ‘1’) but are modeled to have mean values on all other independent variables. The result of 3.5 means that respondents were predicted to report being more than ‘neither likely nor unlikely’ but were not as close to reporting being ‘somewhat likely’. Finally, in

Figure 1, we depict the predicted values on each dependent variable when respondents are modeled to have reported “yes” to each COVID-19 economic displacement experiences. These results easily differentiate the impact of various COVID-19 economic displacement experiences on respondent reports about their likelihood of using one of the four financial stabilization mechanisms.

4.1. OLS Regression

OLS regression was used to estimate the linear association between the independent variables and each of the four dependent variables. The OLS coefficients for any independent variable represent the strength of the measure in predicting the dependent variable (the outcome of interest), holding the other variables constant, whereby positive coefficients indicate a positive relationship and negative coefficients indicate a negative relationship. All estimates used the weighted data and were generated using the svy option in Stata. We utilize OLS regression rather than ordinal logistic regression because the survey instrument presented response options using numbers attached to semantic differential scales, which highlighted contrasts at the ends and contained a “neither” midpoint. We assume that respondents appropriately differentiated across response options and may have seen them as equidistant. To check further, we tested for multicollinearity and examined values of VIF (variance inflation factor) for each variable in each regression equation. No variable registered a VIF value higher than 5, meaning that multicollinearity was not a concern. As another check, we ran the models using ordinal logistic regression and compared the coefficients and error terms. We found no substantive differences; with some minor exceptions, the same variables were found to be significant across the different models.

Table 2 depicts the results of the OLS regression modeling the confluence of factors influencing the likelihood of utilizing AFSs. Overall, each model adequately reflected the trends of observed data:

Credit Cards F (41, 9431) = 22.13,

r2 = 0.11,

p < 0.001;

Payday Loans F (41, 9431) = 47.13,

r2 = 0.24,

p < 0.001;

Public Benefits F (41, 9431) = 48.23,

r2 = 0.21,

p < 0.001;

Family and Friends F (41, 9431) = 32.45,

r2 = 0.15,

p < 0.001. The model

R2 = 0.152. For visual representation of the OLS coefficients, their magnitude and significance, please see the

Appendix A.

Table 2.

Regression results.

Table 2.

Regression results.

| | Credit Card | Payday Loans | Public Benefits | Family & Friends |

|---|

| COVID Economic Displacement |

| Unemployed | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.20 *** | −0.04 |

| Hours reduced, still employed | 0.13 *** | 0.06 | 0.11 ** | 0.06 |

| Business closed | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.00 |

| Unemployed, looking for work | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.36 *** | 0.12 ** |

| Lost access to health insurance | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.18 ** | −0.02 |

| Unable to pay mortgage or rent | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.05 |

| Borrowed money from friends/family | 0.07 | 0.25 *** | 0.01 | 0.51 *** |

| Used food bank/charity | −0.15 *** | −0.05 | 0.40 *** | 0.12 ** |

| Spent money on tech to work at home | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Recent debt experience |

| Credit card | 0.68 *** | −0.00 | 0.13 *** | 0.19 *** |

| Mortgage loan | 0.13 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.03 | −0.01 |

| Auto loan | 0.10 *** | −0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 * |

| Student loan | 0.11 *** | 0.03 | 0.21 *** | 0.23 *** |

| Payday loan | −0.04 | 0.48 *** | 0.05 | −0.12 |

| Other personal loan | −0.10 ** | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.13 *** |

| Prior use of AFS |

| Check cashing store | 0.08 | 0.42 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.01 |

| Payday lending or cash advance | 0.20 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.17 ** | 0.17 ** |

| Pawn shop | 0.05 | 0.20 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.08 |

| Title loan services | 0.10 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Banking access |

| Possession of a bank account | 0.27 *** | −0.05 | 0.18 *** | 0.10 * |

| Attitudinal Factors |

| Hopefulness: Economy | 0.05 *** | 0.02 | 0.04 ** | 0.05 *** |

| Hopefulness: Personal wellbeing | −0.02 | −0.00 | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Trust in banks | 0.05 *** | 0.02 *** | 0.01 | 0.02 *** |

| Socio-geographic Factors |

| Geography: Large urban | 0.12 * | 0.11 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.08 |

| Geography: Large suburban | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.10 | −0.00 |

| Geography: Small suburban | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Geography: Small town | 0.12 * | 0.04 | 0.06 | −0.01 |

| Geography: Rural area | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Gini Index | −0.11 | −0.19 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| Sociodemographic Factors |

| Age | −0.01 *** | −0.02 *** | −0.02 *** | −0.02 *** |

| Gender (Female) | 0.09 *** | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Education | 0.00 | −0.02 ** | −0.03 *** | 0.02 |

| Income | 0.01 * | −0.02 ** | −0.06 *** | −0.02 *** |

| Race/ethnicity: White | 0.04 | −0.14 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.25 *** |

| Race/ethnicity: Latino | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.12 *** | −0.23 *** |

| Race/ethnicity: Black | −0.04 | −0.15 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.17 *** |

| Race/ethnicity: AAPI | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| Marital status (Married) | 0.04 | 0.10 *** | 0.04 | −0.04 |

| Party affiliation (Republican) | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.03 |

| Party affiliation (Democrat) | 0.03 | 0.08 ** | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Party affiliation (Independent) | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- |

| US born | 0.01 | −0.09 ** | 0.05 | −0.06 |

| Voter registration (Registered) | −0.15 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.08 ** | −0.08 ** |

Regression analyses revealed that borrowing money from friends and family (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) was found to be a significant and positive predictor for indicating a likelihood of utilizing payday loans, the proxy for AFS use. This study also found that payday loan experience (β = 0.48, p < 0.001), prior use of a check-cashing store (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), prior use of payday loan (β = 0.67, p < 0.001), and prior use of a pawn shop (β = 0.20, p < 0.05) significantly predicted utilization of payday loans. Trust in banks is also a positive predictor of AFS use (β = 0.02, p < 0.001), whereby higher levels of trust predict a higher degree of utilizing a payday loan. Mortgage debt experience (β = −0.15, p < 0.001), on the other hand, was found to be a significant negative predictor, by which having mortgage debt reduced one’s utilization of payday loans.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

The displacement factor, borrowing money from friends and family is the only factor that predicted payday loans. As such, we reject the first hypothesis, H1. Further, for H2, we find that prior experience with payday lending, with the exception of auto title borrowing, predicts future AFS use. Specifically, prior check cashing store use (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), prior payday lending experience (β = 0.67, p < 0.001), and prior pawn store use (β = 0.20, p < 0.05) positively predict AFS use. We reject this hypothesis as all prior AFS uses did not predict future AFS use. Finally, we find that there are differences across ethno-racial identities (H3). There is a negative relationship between ethno-racial identities and AFS use: White (β = −0.14, p < 0.01) and Black (β = −0.15, p < 0.001). Comparatively, respondents of Latino identity neither were more nor were less likely than respondents of AAPI identity (the excluded baseline category) to report a likelihood to use payday loans. Thus hypothesis H3 is confirmed even after controlling for factors like education, income, immigrant birth stratus, and party affiliation, age, and prior experience with AFS products, one’s ethno-racial identity did impact their reported likelihood using payday loans.

We evaluate the magnitude of the examined relationships in

Figure 1, by using estimates from the OLS regression results to graph the predicted value on each of the four dependent variables by experience with each of the nine COVID-19 economic displacement factors while holding all the other independent variables at their sample means. The bar heights on

Figure 1 depict the predicted value on the response to a question probing specific use of a financial stabilization measure, whereby responses run from ‘1 = very unlikely’ to ‘5 = very likely’ and whereby experience with each COVID-19 displacement factor is set to ‘1’ or ‘yes’. This figure shows that credit card use consistently exhibited the highest predicted levels. In contrast, payday loan use exhibited the lowest values suggesting limited reliance regardless of displacement type. There was greater reliance on public benefit depending on the displacement factor; however, the greatest magnitude of difference was observed in borrowing from friends and family.

These results can be interpreted through the ABC-X model framework. COVID-19 displacement factors (A) largely did not predict payday loan use, with the exception of borrowing from family and friends suggesting that only direct resource depletion triggered crisis-level AFS reliance. Prior use of AFS (B) strongly predicted future use, validating the idea that previously relied-upon behavioral resources are reused under stress. Attitudinal variables (C), particularly trust in banks, also predicted AFS use, albeit in directions that sometimes contradict expectations. The dependent variables (X) (payday loans, credit card use, public benefits, and borrowing from family and friends) thus represent the outcomes of different combinations of stressor–resource–perception interactions.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine how individuals responded to COVID-19 economic displacement through various financial coping strategies, including payday loans (as a proxy for AFSs), credit cards, public benefits, and borrowing from family and friends. These outcomes provide insight into both formal and informal strategies to manage financial stress.

The first hypothesis, which posited that COVID-related economic displacement would influence the likelihood of AFS use, was largely unsupported. While unemployment, reduced hours, loss of health insurance, and housing instability were widely reported during the pandemic, only one displacement factor—borrowing from family and friends—was a significant and consistent predictor of payday loan use in this study. This suggests that only immediate and personal forms of resource depletion may push individuals toward high-risk financial coping mechanisms. Contrary to expectations, most formal displacement indicators had limited explanatory power when predicting reliance on payday loans or other financial strategies. This finding challenges prevailing assumptions about the direct link between macro-level economic disruptions and individual-level financial behavior.

The second hypothesis received partial support. Prior use of specific AFS products—including payday loans, check cashing services, and pawn shops—significantly increased the likelihood of continued use, particularly payday loan utilization. This finding aligns with previous research indicating a path dependency in financial behavior, where individuals repeat coping strategies they have used in the past, even if those strategies carry long-term financial risks [

15,

24,

26]. However, not all forms of prior AFS use predicted future reliance; for instance, title loan use did not significantly impact any financial behavior. These findings highlight the importance of disaggregating AFS types when examining behavioral continuity. This disaggregation will be helpful when designing interventions and implementing policies to protect and support AFS users.

The third hypothesis, which suggested ethno-racial identity would influence the likelihood of using financial coping strategies, was supported, although the findings were more nuanced than anticipated. While Black and White respondents were significantly

less likely than AAPI respondents to report payday loan use, Latino respondents showed no statistically significant difference from the AAPI baseline group contradicting prior research [

48]. Interestingly, the data showed that non-Hispanic Black individuals were not more likely than White respondents to rely on AFSs. Instead, both groups showed lower likelihoods than their AAPI counterparts. Much of the research suggests that minority groups, specifically Black and Latino individuals, are more likely to use AFSs; however, our research does not support this. Perhaps there were more resources available during the pandemic reducing the need for minority populations to seek liquidity from AFSs. This unexpected pattern suggests that cultural, structural, and institutional factors influencing financial behavior may vary considerably across ethno-racial identities and challenges the assumption of a uniform trajectory of AFS reliance among racially minoritized populations. In this study we examine various sociodemographic variables. The findings suggest White and Black individuals are less likely to use AFSs as compared to other racial groups. The literature suggests non-White minoritized communities are the predominant users of AFSs [

49]. Brevoort et al. found that low-income, Black and Latino individuals were more likely to be credit invisible or to have unscored credit histories—all of which could lead to AFS use [

50]. However, our data show that race has a limited differential impact on credit card and payday loan use. For payday loans, there is a negative relationship for Black and White individuals and AFS use. For payday loans, Black and White individuals were significantly less likely to use them, suggesting that other financial factors contribute more to reliance on payday loans. There was also a negative relationship between ethno-racial identity (White and Black) and AFS use, which conflicts with much of the literature that identifies Black individuals as predominant users of AFSs.

For individuals with unmet financial needs, family and friends are a potential source of support. Research has found that individuals often rely on financial support from family and friends when facing financial challenges and other hard times [

51,

52,

53]. Our findings suggest that borrowing from friends and family and payday lenders tend to serve as the last resort for most. This makes sense because an individual has likely explored all options by the time they turn to friends and family for support. Moreover, this finding is helpful to understand AFS users—borrowers likely do not turn to these nontraditional financial providers first.

Prior debt experience with both mortgage and payday loans were also predictors of AFS use. Given that housing payments are the single largest household budget expenses, it is plausible that borrowers may seek payday loans to address financial obligations. The literature also suggests that once an individual borrows a payday loan, a cycle of borrowing has begun [

54]. There is also strong evidence for prior use of AFSs. Previous payday loan use predicted use of credit cards, payday loans, public benefit use and borrowing from friends and family. This finding may demonstrate the level of financial stress or burden that an individual is experiencing. As such, it was not surprising that prior use of check cashing, payday loans, or pawn shops predicted AFS use during the COVID-19 pandemic—perhaps during this economic crisis any money or money from any means seemed appropriate.

The literature and current research on unbanked and underbanked individuals suggest that individuals are more likely to use AFSs when they have limited or a lack of trust in banks. In this study, it was surprising that having trust in banks was a positive predictor of AFS use. This suggests that institutional trust does not preclude reliance on high-cost lending. Another surprising finding was that being unbanked or underbanked was not a predictor of AFS use. These findings contradict with the prior research [

49,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60] that highlights the impact of financial inclusion on economic resilience.

Consistent research suggests that the typical AFS user profile includes individuals that are less educated, minority, middle aged (31–45), lower income, unemployed, renters, from larger households, and unbanked [

1]. Like other scholars, we found that AFS use is correlated with having less education and living in urban areas [

53]. The contextual variations by community type underscore the importance of localized policy responses, as urban residents face distinct financial challenges compared to their rural counterparts. Further, in current years, many banks have closed storefronts in large urban areas perhaps creating a void—and inadvertently making it easier for nontraditional financial services to fill said void. Finally, we find that party affiliation (specifically, being a Democrat) and voter registration status (specifically, being registered to vote) are also predictors of AFS use. Voter registration status may suggest that individuals are civically engaged. Perhaps there is an opportunity to create a compelling public awareness campaign that will motivate consumers to save for emergencies.

Throughout the pandemic, credit card debt increased roughly 30 percent for all Americans [

50] and there was an increased use of AFS such as pawnshops, payday lenders, rent-to-own stores, money transmitters, and check cashers [

58]. This is attributed to the pandemic’s impact on employment and the economy. It is important to note factors that may influence credit card use, such as reduced work hours and income, as individuals seek to meet financial obligations. Credit cards, one of the most accessible forms of credit, were one of the first sources for families of color who had to continue to pay bills and other essential expenses while they faced sudden decreases in income related to job losses [

59,

60] yet our findings do not support this.

The use of OLS regression in this study aligns with prior research that examines financial behavior determinants, including the research of Lusardi and Tufano [

51] who explored debt literacy and its relationship with financial decision-making. Interpreting the OLS findings through the lens of the ABC-X model provides several insights. Interpreting the theoretical underpinnings of the ABC-X model, COVID-19 displacement factors (Stressor [A]) generally did not predict AFS use—except borrowing from family and friends—suggesting that only direct resource depletion triggered crisis-level AFS reliance. In accordance with the ABC-X model, individuals and families act upon real (or perceived) resources that they possess or consider accessible especially under stressful circumstances [

55]. While the stressors measured (e.g., COVID-related job loss, pay cuts) were not consistently predictive of payday loan use, prior behavioral responses (e.g., use of check cashing or pawn services) were strong predictors. This supports the idea that families fall back on familiar coping strategies during crises. Perceptual variables, like trust in banks, played a nuanced role—indicating that even those who trust formal financial institutions may still turn to AFSs. The various outcomes, particularly payday loan use, reflect not only financial desperation but also a dependence on previous behaviors and belief systems. COVID-19 displacement did not uniformly produce crisis-level AFS use, indicating that stressors alone are insufficient predictors. In terms of Resources [B], prior AFS use significantly predicting continued use under stress, highlighting the path dependency of financial coping mechanisms. Behavioral resources, especially prior experience with AFS, emerged as critical drivers of financial coping strategies. Next in the model, Perceptions [C], measured in this study as attitudinal factors such as trust in banks, though counterintuitive, also influenced financial behavior. Higher trust in banks correlated with greater payday loan use, suggesting complex relationships between institutional trust and coping behavior. Trust in banks, though counterintuitively associated with increased payday loan use, points to complex perceptions of institutional reliability or desperation-based decision-making. Finally, the crisis outcome [X], is represented by the four financial responses (credit cards, payday loans, public benefits, and family support) are outcomes arising from different combinations of stressors, available resources, and perceptions. The financial behaviors observed—whether seeking credit, borrowing informally, or utilizing benefits—are distinct yet interconnected outcomes shaped by the interplay of stressors, resources, and perceptions.

6. Implications

The global pandemic may have served as a once-in-a-century event to expand the AFS consumer base. The findings from this study have several implications for policy, practice, and future research. First, the limited predictive power of many displacement factors suggests that broad-based relief efforts may not reach those most at risk of engaging with high-cost financial products. Interventions that focus on immediate liquidity needs—particularly among those who lack sufficient social safety nets—may be more effective. Next, the strong predictive power of prior AFS use highlights the need for interventions that disrupt recurring behavioral patterns. Financial coaching, credit-building programs, and community-based banking solutions can serve as potential alternatives for those caught in cycles of predatory lending. In fact, counselors and educators should tailor interventions and strategies when individuals have prior AFS experience. Counselors can focus on budget management and debt consolidation techniques to reduce dependence on payday loans and public benefits. Several predictors emerged as significant influencers on financial behaviors. Financial counselors can use these findings to support particularly vulnerable individuals to reduce reliance on alternative financial services. Third, the ethno-racial disparity in financial coping behavior underscore the necessity of culturally informed financial education and services. A one-size-fits-all model may miss the structural and cultural dynamics that shape financial behavior differently across groups. Finally, the positive association between trust in banks and payday loan use requires deeper exploration. Future research into trust may complement the work of Chawla et al. [

61]. It may reflect limited perceived alternatives or a compartmentalized trust, where individuals simultaneously engage with formal institutions and high-risk options out of necessity. Strengthening access to inclusive, affordable credit products could shift this dynamic.

Our findings support prior research that AFS users are trapped in a cycle of debt. This debt cycle coupled with financial stress is detrimental for individuals and families. The findings from this study are relevant to the economic resource management and financial wellbeing literature. Educators, researchers and practitioners can use these findings to better understand how consumers cope during crisis and when they turn to AFS to mitigate financial precarity. Since people turn to AFS because they have limited options. As such, these findings can inform advocacy efforts, such as stronger consumer protections including limits to interest rates, increased transparency in AFS terms, and restricting rollovers and renewals.

This study makes several important contributions to the literature on financial coping, alternative financial service (AFS) use, and household behavior under economic stress. First, by examining four distinct financial coping strategies—credit card use, payday loans, public benefits, and borrowing from family and friends—this study broadens the conceptualization of financial coping [

25,

26]. The findings also complicate existing narratives that link economic shocks directly to AFS use. Contrary to conventional wisdom, most COVID-related displacement factors were not significant predictors of payday loan use. This suggests a need to re-evaluate how economic precarity translates into financial behavior and highlights the importance of personal networks and prior behavioral patterns. Finally, the findings reveal that ethno-racial identity plays a nuanced role in financial coping behavior. The fact that Black and White respondents were less likely than AAPI respondents to report payday loan use—and that Latino respondents showed no significant difference—adds complexity to existing understandings of racial disparities in financial vulnerability. This calls for more culturally responsive and disaggregated approaches in future research and targeted interventions.

Building on these contributions, several avenues for future research are recommended. Future research should employ longitudinal studies to examine trends in financial coping strategies, particularly in response to recurring or compounding economic stressors. This would provide greater insight into behavioral persistence and transitions between informal and formal financial tools. The unexpected positive association between trust in banks and payday loan use warrants qualitative investigation. Future studies could explore how individuals conceptualize trust in financial institutions, and why that trust may coexist with reliance on high-risk credit products. Researchers should also assess the effectiveness of interventions aimed at disrupting cycles of AFS use. This includes evaluating community lending programs, financial education efforts, and behavioral nudges designed to promote healthier long-term financial strategies. Finally, replicating this study in global contexts or with different crisis events (e.g., natural disasters, inflation spikes, or war) could provide valuable cross-cultural comparisons and test the generalizability of the findings across systems of financial regulation and social safety nets.

8. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic may have created a perfect storm—one that may have made it easier and more compelling for individuals without access to traditional banking and credit solutions to consider AFS when routine expenses exceeded income or when dealing with emergencies. Undoubtedly, the intensity, depth, and nature of COVID-related precarity required fast liquidity to manage living expenses, especially among vulnerable and marginalized communities. Given the pervasiveness and location of AFS providers, especially in communities of color with limited access to mainstream financial institutions, this study seeks to examine the prevalence of AFS use in 2020 and early 2021. Using the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Politics Study, we examine (1) COVID-19 economic displacement factors, (2) prior AFS use, and (3) sociodemographic factors that influence AFS use. This study found that borrowing money from friends and family was the only statistically significant COVID-19 economic displacement factor to predict AFS use. We also find that prior experience with payday lending, with the exception of auto title borrowing, predicts future AFS use through the proxy of payday loans. Finally, we find that there are differences across ethno-racial identities when comparing AFS use. These findings underscore the critical financial vulnerabilities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Most importantly, this study amplifies the need to support individuals through education and advocacy before they borrow through AFS—for the first time. While the financial stress associated with COVID-19 may be unprecedented, this finding suggests targeted interventions can be employed to help individuals break the cycle of AFS use and find less expensive funds in case of a financial emergency.

This study offers new insights into the multifaceted nature of financial coping during economic crises. While pandemic-related disruptions were expected to drive individuals toward AFS, our findings indicate that pre-existing behavioral habits and ethno-racial identity played more consistent roles in shaping financial responses. The use of the ABC-X framework allowed for a nuanced understanding of how stressors, resources, and perceptions interact to produce different financial outcomes.

Ultimately, addressing AFS use requires more than mitigating economic hardship; it demands systemic efforts to reshape financial norms, increase access to safer credit options, and provide behavioral support for those that rely on high-cost financial tools, including AFS. Future research should further explore these dynamics using longitudinal data and consider how intersectional identities mediate financial coping behavior over time.