1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about a level of global disruption unprecedented in recent history. It affected nearly every aspect of life, but its impact was particularly acute in three interrelated domains: education, employment, and entrepreneurship. As schools and universities were forced to shut their doors, learning was suddenly moved online, creating significant gaps in access, engagement, and the overall quality of education [

1,

2]. For students in higher education, this disruption extended beyond academic routines; it reshaped long-term career planning and professional development in ways that are still unfolding [

3,

4].

At the same time, global labor markets contracted sharply. Job losses, hiring freezes, and economic instability became defining features of the pandemic era, especially for younger generations preparing to enter the workforce [

5]. In response to these shifts, entrepreneurship gained renewed relevance, not only as a means of economic survival but as a way to reclaim agency and adapt creatively to uncertain conditions [

6]. However, the appeal of entrepreneurship was accompanied by heightened concerns over risk and uncertainty [

7], limited access to capital [

8], consumer behavior pattern shifts [

9] and weakened support networks [

10] complicating the decision-making process for many aspiring entrepreneurs.

For undergraduate business students, arguably among those most exposed to entrepreneurial thinking through formal education and experiential learning [

11], the pandemic posed a particularly complex challenge. These students often occupy a transitional space, academically primed to engage with risk, innovation, and opportunity, yet not fully embedded in the labor market. As such, they represent a critical population for examining how perceptions of entrepreneurship evolve under crisis conditions. The uncertainty introduced by the pandemic was not limited to economic factors; it intersected with personal aspirations, shifting life priorities, and anxieties about the future [

12]. It is within this context of overlapping educational, economic, and psychological instability that this study is situated, offering a timely investigation into how emerging professionals make sense of entrepreneurship in a world fundamentally altered by global disruption.

Despite the growing body of literature on the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19, relatively little is known about how these changes have shaped students’ professional aspirations, especially their interest in entrepreneurship. Much of the existing research has focused on macro-level trends, such as shifts in business activity [

13], employment data [

5], and institutional responses [

9]. While valuable, these studies often overlook the personal narratives of young adults who are still forming their entrepreneurial identities within academic settings. There is a notable gap in qualitative research that investigates how the pandemic influenced students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial intention is shaped not only by education and motivation but also by context-specific factors such as perceived risk, confidence, and resilience [

14,

15]. The pandemic offers a unique lens to examine how these factors interact during times of widespread disruption. What is largely missing from the current scholarly conversation is a narrative-driven account of how students themselves understand and articulate the impact of the pandemic on their entrepreneurial thinking. Their perspectives are critical for building a more holistic understanding of how entrepreneurial mindsets develop under conditions of crisis, and for informing policies and educational practices that are responsive to these realities.

This study aims to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate business students in the U.S. It responds to the broader problem that little is known about how crisis events shape intention formation among students in business disciplines, particularly within the U.S. context. By focusing on a group academically engaged with entrepreneurship but still navigating early career uncertainty, the research investigates how students perceive entrepreneurship as a viable career path in the post-pandemic context. Rather than relying on predefined variables or survey instruments, this study adopts a qualitative approach to capture the complexity of students’ lived experiences. It seeks to understand how the pandemic influenced their attitudes toward risk, opportunity, independence, and self-efficacy which are core dimensions of entrepreneurial intention, as established in the literature [

14,

16,

17]. Through in-depth interviews, the study examines how some students came to view entrepreneurship as a means of resilience and self-direction, while others were drawn to more conventional or perceived stable paths. Guided by the need to better understand how these dynamics shape entrepreneurial decision-making, the study is driven by the following research question: How has the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate business students, and what factors have shaped these changes? The following section provides national-level context by outlining how the COVID-19 pandemic shaped the U.S. labor and education landscape, helping to frame the conditions under which students formed or reconsidered their entrepreneurial intentions.

2. Entrepreneurship in the United States During COVID-19

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 produced significant structural changes in the U.S. labor market, altering both the availability of entry-level jobs and students’ perceptions of career stability. The pandemic profoundly disrupted the entrepreneurial landscape, leading to significant business closures and reshaping the nature of new ventures. Between February and April 2020, the number of active business owners in the U.S. plummeted by 3.3 million, marking a 22% decline, the largest on record. This downturn disproportionately affected minority-owned businesses, with African-American business activity dropping by 41%, Latinx by 32%, and Asian by 26% [

18]. Despite substantial federal relief efforts, including the Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loans, which collectively disbursed over

$1.2 trillion to support small businesses [

19], many enterprises, particularly those in sectors reliant on in-person interactions like hospitality and personal services, struggled to survive.

Paradoxically, the pandemic also ignited a surge in entrepreneurial activity. In 2021 alone, Americans filed 5.4 million new business applications, the highest annual total on record [

20]. This boom was driven by various factors, including shifts in consumer behavior, advancements in digital technology, and a reevaluation of work–life priorities. Notably, many of these new ventures were smaller in scale, with startups formed during the pandemic averaging 4.6 employees, down from 5.3 in the previous year [

21]. This trend reflects a move toward leaner business models, often leveraging remote work and digital platforms to operate efficiently. The pandemic accelerated the digital transformation of businesses, with many entrepreneurs pivoting to online models to reach consumers confined to their homes [

9]. E-commerce sales surged, accounting for 16.1% of all U.S. sales, up from 11.8% in the first quarter of 2020 [

22]. This shift not only provided a lifeline for existing businesses but also lowered barriers to entry for new entrepreneurs, particularly in sectors like online retail, digital services, and food delivery.

Consumer behavior underwent significant changes during the pandemic, influencing entrepreneurial opportunities. Homebound consumers abandoned ingrained shopping habits, propelling e-commerce into hyperdrive and compressing a decade’s worth of digital adoption into 100 days [

23]. The increased demand for convenience, safety, and contactless services created new niches for entrepreneurs to explore, from virtual fitness classes to telehealth services [

24].

3. Student Entrepreneurial Intentions During COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic served as both a disruption and a catalyst for young and emerging entrepreneurs, particularly students. As academic and employment systems froze under global lockdowns, students found themselves re-evaluating career pathways and exploring entrepreneurship as either a fallback strategy or an aspirational pursuit. While traditional business environments contracted, new opportunities emerged, encouraging entrepreneurial engagement among youth populations across diverse contexts [

25].

Studies conducted during the pandemic show that student entrepreneurial intentions were not uniformly diminished by crisis conditions. In some contexts, entrepreneurial intentions remained stable or even increased. A longitudinal study by Botezat et al. [

26] revealed that students enrolled in entrepreneurship education programs in Romania experienced a rise in entrepreneurial intentions over the course of the pandemic. Using a Latent Change Score model, the authors demonstrated that individuals with lower initial entrepreneurial intentions scores showed greater change, and that factors such as entrepreneurial self-efficacy and access to resources played moderating roles. Their study highlights not only the resilience of entrepreneurial interest, but also the importance of structured university programs in fostering that growth. Other studies have affirmed this trend. For instance, Lopes et al. [

27] found that Portuguese university students maintained strong entrepreneurial intentions during the pandemic, with entrepreneurship education and perceived behavioral control acting as key influencers. Similarly, Siddiqui and Ahmad [

28], drawing from an Indian sample, argued that COVID-19, rather than deterring entrepreneurial intention, heightened student awareness of opportunity structures and reinforced the value of independence and innovation in times of uncertainty.

However, the pandemic did alter the factors shaping these intentions. Hernández-Sánchez et al. [

29] observed that psychological traits, e.g., optimism, proactivity, and resilience, were crucial in mediating the impact of pandemic-related stress on entrepreneurial motivation. Trif et al. [

30] added that risk-taking and innovativeness significantly influenced entrepreneurial intentions, but these effects were often moderated by the institutional environment. Their findings support the assertion that entrepreneurial intention during crises cannot be divorced from contextual and psychological dimensions. The university environment has, indeed, emerged as a central enabler or barrier during the pandemic. Domingo [

31], in a study of entrepreneurship students in the Philippines, found that hands-on curricular experiences, peer mentorship, and digital training played critical roles in preparing students to start businesses amidst community lockdowns and social restrictions. Students adapted by launching online-based micro-businesses from their residences, often driven by the dual motivations of earning income and applying classroom knowledge. This aligns with Menshikov et al. [

32], who argue that digital transformation and online education have created hybrid spaces where entrepreneurial intentions are shaped both by necessity and technological accessibility.

Other researchers have emphasized the diversity of student responses. Schumm et al. [

33], focusing on the U.S., found that while some students felt motivated to pursue self-employment due to job market instability, others became more risk hesitant. Their findings underscore the uneven psychological impacts of the pandemic and the ways in which perceived security, family influence, and economic background mediate entrepreneurial choices. Caglayan and Ucel [

34], examining Turkish students, similarly reported a mix of motivations, ranging from autonomy to financial survival, further emphasizing the role of socio-economic and cultural context.

4. Theoretical Framing: Crisis, Decision-Making, and Resilience

Understanding how undergraduate business students responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of entrepreneurial intention requires a theoretical lens capable of capturing the complexity of decision-making under uncertainty. This study draws on three complementary frameworks to interpret how crisis conditions influence entrepreneurial thinking, motivation, and action. These are (1) effectuation theory, (2) resilience theory, and (3) the theory of planned behavior.

Effectuation theory, introduced by Sarasvathy [

35], offers a useful model for understanding entrepreneurship not as a linear or predictive process, but as a flexible and adaptive one. Effectual reasoning begins with the means at hand, who I am, what I know, and whom I know, rather than pre-determined goals. Especially in times of disruption, such as a pandemic, entrepreneurs are more likely to engage in effectual logic, seeking to control uncertain outcomes by leveraging existing resources rather than relying on forecasts. For students navigating volatile career landscapes, this approach may explain a shift toward resource-based decision-making, experimentation, and risk tolerance in entrepreneurial pursuits.

Resilience theory provides a psychological and behavioral framework for understanding how individuals respond to adversity. In the context of youth entrepreneurship, resilience is not merely the ability to endure hardship, but the capacity to adapt, recover, and innovate in response to crisis. As research has shown, traits such as optimism, self-efficacy, and adaptability can buffer the negative impacts of stress and uncertainty [

29]. The entrepreneurial intentions of students during COVID-19 may therefore be seen not only as economic calculations, but as expressions of psychological resilience, shaped by both internal traits and external support systems.

Lastly, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [

36], frequently applied in entrepreneurship research, underpins this study’s understanding of intention formation. According to the TPB, entrepreneurial intention is influenced by attitude toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. These elements are shaped by the broader environment, including pandemic-related disruptions to education, employment, and personal aspirations. As such, TPB provides a foundation for analyzing how students weighed entrepreneurial risks and rewards during an unprecedented crisis.

Together, these frameworks provide a multi-layered view of how crisis conditions influence entrepreneurial intention. While TPB captures the cognitive structure of intention, effectuation theory and resilience theory extend the analysis into action and adaptation, allowing for a more detailed interpretation of student responses in a post-pandemic landscape.

5. Methodology

In contrast to more conventional methodological presentations, this section combines narrative reflection with theory-driven rationale. This stylistic decision was intentional and rooted in a growing tradition within qualitative research that values the interplay of lived experience, reflexivity, and scholarly interpretation [

37,

38]. Narrative inquiry and reflective writing are not only stylistic choices but epistemological commitments, particularly when the aim is to understand how individuals make meaning under conditions of uncertainty [

39,

40]. In the context of a global crisis like COVID-19, this approach offers a way to capture not just what was said, but how participants emotionally and cognitively navigated disruption. This methodology aligns with an interpretivist stance, in which knowledge is co-constructed through dialogue, theory, and situated context [

41].

This study was conceived and conducted in the long shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, during a time when both university instruction and career planning had undergone profound shifts. Interviews took place in 2022, when many students were still struggling with the disruptions to their education and aspirations. It became clear early in the process that traditional, quantitative tools would not suffice to capture the complexity of their experiences. Instead, a qualitative, interpretive methodology was adopted to explore not just what students thought about entrepreneurship, but how they thought about it, especially in the context of crisis and uncertainty.

The methodological choices were guided by the study’s theoretical framing. Effectuation theory, resilience theory, and the TPB, each of these emphasizes subjectivity, decision-making under uncertainty, and adaptive behavior. These frameworks provided not only the conceptual lens for analysis but also the rationale for privileging student voices. Effectuation suggests that individuals act not on predictive models, but by leveraging available resources in real time, an approach mirrored in the use of in-depth and open-ended interviews that allowed participants to narrate their own logic of action. Resilience theory, similarly, frames intention as a response to adversity, shaped by both internal traits and contextual supports. And TPB offered a cognitive structure through which to understand how perceived risk, control, and norms interacted in shaping student intentions.

A total of 31 undergraduate business students (18 female and 13 male participants) from a public Midwestern university were interviewed, all of whom had some academic or personal exposure to entrepreneurship. This participant group was selected due to their relevance to the research aims. Business students are often exposed to entrepreneurship coursework and are situated at a transitional stage where professional identity and career planning begin to solidify. This makes them particularly well-positioned to reflect on how uncertainty influences entrepreneurial thinking [

14,

42]. Although not all students expressed an intent to start a business, their responses, whether supportive, hesitant, or rejecting of entrepreneurship, provide valuable insight into how the idea of entrepreneurship is socially and psychologically negotiated in a post-pandemic world. Participants were recruited through an email invitation sent to all business students in the department, inviting those interested in sharing their experiences to participate in the study. Those who responded and expressed interest were contacted directly to schedule interviews. This reflects a voluntary, self-selected sampling strategy, typical in qualitative research that prioritizes depth of reflection over representativeness. Recruitment and interviewing continued until thematic saturation was reached; that is, no new concepts or patterns were emerging from the data [

43]. Interviews were conducted via Zoom, typically lasting between 45 and 70 min. Conversations were semi-structured, allowing for consistency in core questions while also creating space for personal narratives to emerge [

41]. This interview format was selected for its appropriateness in addressing “how” and “why” questions, particularly those related to meaning-making and identity construction under conditions of disruption [

44]. Questions explored participants’ entrepreneurial interests before and during the pandemic, their perceived barriers and opportunities, and their emotional responses to uncertainty.

Thematic analysis was conducted manually, following the structured approach adapted from Miles et al. [

45] model of qualitative analysis. The process involved three core actions: data reduction, data display, and drawing/verifying conclusions. Interview summaries were coded by hand using colored highlighters to identify recurring themes and sub-themes across transcripts. Marginal notes and memos were used throughout to aid interpretation, and visual layouts were created to compare patterns across participants. This method allowed for a deep, iterative engagement with the data and mirrored the hands-on techniques used in prior student-centered studies [

46,

47], where close manual engagement with the data allowed for deeper insight into the cognitive and emotional dimensions of participant responses [

48]. While the lead author conducted the data analysis solely, confirmability was maintained by an audit trail and peer debriefing with the co-author.

This study draws on the same dataset used in two previous publications by the first author (references removed for peer review), which explored students’ entrepreneurial aspirations and marketing-related challenges. In contrast, the present manuscript focuses on how students interpreted the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on their entrepreneurial intentions, analyzed through a theoretical lens combining the Theory of Planned Behavior, effectuation theory, and resilience theory. The focus on crisis-induced reflection, resilience, and identity formation offers a distinct and novel contribution that did not feature in earlier publications. The reuse of qualitative data in this case is consistent with best practices in the field, which emphasize that secondary analysis can yield valuable new insights when the research question and conceptual framework are substantially different [

49,

50]. Moreover, ethical considerations have been carefully observed, including IRB approval, informed consent, and data protection in line with recommended standards for qualitative data reuse.

6. Results

The data analysis from the interviews revealed a range of perspectives on entrepreneurship, shaped by the uncertainties, disruptions, and re-evaluations that students experienced during the pandemic. While not all participants shared the same view of entrepreneurship as a desirable or realistic path, their reflections offered layered insights into how intentions were reshaped by the crisis. For some, entrepreneurship emerged as a form of agency; for others, it became synonymous with risk and instability. Still others expressed shifts in priorities that repositioned entrepreneurship in relation to broader life goals.

Rather than seeking agreement or general patterns, the analysis focused on the tensions, contradictions, and narrative turns within and across student accounts. The interpretation of these narratives was informed by the study’s three guiding frameworks: effectuation theory, resilience theory, and the TPB, which offered conceptual tools for understanding how students negotiated risk, control, motivation, and self-efficacy in a disrupted world. Five core themes were identified: (1) entrepreneurship as a strategy of control, (2) pandemic-triggered caution and risk aversion, (3) shifted priorities and reimagined career paths, (4) learning in crisis and the role of online education, and (5) entrepreneurial identity in formation. Each is presented in the sections below, supported by direct quotations to preserve the voice and complexity of the participants’ experiences.

6.1. Entrepreneurship as a Strategy of Control

Several participants (n = 17) described entrepreneurship not primarily as a path to wealth or innovation, but as a way to reclaim a sense of control over their lives during a time marked by unpredictability. For these students, the pandemic had destabilized many of the traditional career paths they had anticipated. For example, internships were canceled, hiring freezes became common, and corporate career structures suddenly appeared less reliable. In contrast, entrepreneurship offered an alternative path that, although uncertain, placed decision-making and direction in their own hands. One participant explained:

“It wasn’t just about starting a business for the sake of being a boss or something. It was more like…I wanted to be the one deciding what happens next… Everything else felt like it was falling apart, but if I could build something from scratch, at least I’d have that control.”

(P22)

This response reflects a core principle of effectuation, where individuals act not based on prediction or long-term forecasting, but based on the resources and agency they currently have. In this context, entrepreneurship was less about executing a fully formed plan and more about starting with what was available. This was a mindset echoed by eight participants who described similar decision-making logic.

Participants (n = 9) emphasized the appeal of autonomy and the ability to “pivot” quickly in contrast to the rigidity of corporate structures. For these students, entrepreneurship represented a more flexible, responsive way to navigate future disruptions. Participant 24 said,

“When you’re working for a company, they decide if you stay or go. And during COVID, so many businesses were letting people go or downsizing… You could do everything right and still lose your job. But if it’s your thing, then at least you get to make that call… even if it’s hard.”

(P24)

Participant 11 similarly noted:

“I wasn’t aiming to get rich. It was just… if I could make something work, even a little thing, then I wouldn’t feel like I was waiting around for the world to go back to normal.”

(P11)

Within the framework of the TPB, these reflections suggest a positive shift in attitudes toward entrepreneurship and an increased perception of behavioral control. Ten participants expressed that the idea of owning their own venture felt more empowering than waiting for uncertain job opportunities to materialize.

At the same time, control was not necessarily equated with success. Some participants (n = 6) acknowledged the challenges of entrepreneurship but framed it as an emotionally stabilizing force, a space where initiative could counterbalance external chaos. For many, it was less about immediate outcomes and more about the ability to shape those outcomes on their own terms.

6.2. Pandemic-Triggered Caution and Risk Aversion

While some students saw entrepreneurship as a path to reclaim agency, fourteen participants expressed hesitation or outright reluctance to pursue entrepreneurial activity in light of the pandemic’s economic and social consequences. For these students, the crisis intensified a sense of vulnerability, financial, emotional, and professional, that made entrepreneurship seem more uncertain and riskier than ever before. Their narratives were marked by ambition in the face of external volatility, where the freedom and flexibility often associated with entrepreneurship began to look more like exposure and unpredictability. Participant 11 reflected:

“Starting something felt way too risky at that time... I saw businesses around me shutting down like restaurants, stores, even some online stuff… It just made me think, maybe this isn’t the time to gamble on something so unstable.”

(P11)

This response captures a widespread perception that entrepreneurship, while potentially empowering, was also filled with risk. Under the TPB, these students exhibited low levels of perceived behavioral control, often citing a lack of financial security, insufficient experience, and reduced confidence in their ability to successfully manage a business in a disrupted environment. The pandemic seemed to diminish not only external opportunities but also internal belief in entrepreneurial readiness.

Nine participants mentioned that witnessing the struggles of entrepreneurs in their immediate social circles played a decisive role in shaping their attitudes. Several referenced family members whose businesses were severely impacted or shut down during the crisis. One student explained, “My uncle runs (a small business) and COVID nearly destroyed it… Watching him go through that changed how I feel about doing something like that myself.” (P5) Another participant described a similar concern saying “I had a part-time job at a café and saw firsthand how hard it was to survive… My boss was barely hanging on… it was just stressful all the time. I realized I’d rather not be the one carrying all that.” (P13) For these students, entrepreneurship shifted from being a symbol of independence to a reminder of fragility. Seeing established business owners struggle, lay off employees, or lose their life’s work instilled a caution that was less theoretical and more intuitive. The downturn in the job market, while frightening, still appeared less personally risky than starting a new venture from scratch in an unstable economy.

Some participants (n = 6) expressed a clear preference for salaried employment with structured benefits and predictable expectations. They associated entrepreneurship with emotional burnout, financial loss, and constant adaptation, and burdens they felt ill-equipped to bear at this stage in their lives. One participant noted, “At least with a job… you kind of know what’s coming. With your own thing, you could lose everything overnight… and that’s what I saw happen to a lot of people.” (P22) In this context, attitudes toward entrepreneurship became more cautious, risk-averse, and strategic. Even those who had once felt excited about starting their own venture spoke about the need to “wait it out,” “build a cushion,” “save some cash first”, or “get experience first.” While the entrepreneurial mindset was not entirely rejected, it was deferred to a time perceived as more stable and forgiving. This temporal distancing reflects a rational, resilience-informed response to crisis, yet not an absence of ambition, but a shift in how and when that ambition could be realistically pursued.

Interestingly, five participants also mentioned social pressure from family and peers to avoid entrepreneurship at that time. In these cases, subjective norms appeared to influence decision-making, reinforcing the idea that entrepreneurship was no longer socially endorsed in the same way. Rather than encouraging innovation, the dominant message from close circles was to prioritize safety, security, and structure.

This pattern reflects what prospect theory identifies as loss aversion, when faced with uncertainty, individuals tend to prioritize avoiding loss over pursuing uncertain gains [

51]. In the context of the pandemic, students’ heightened sensitivity to risk likely shaped their reduced entrepreneurial intentions, even when interest or aspiration remained [

52].

6.3. Shifted Priorities and Reimagined Career Paths

Beyond risk perception, many students described a more subtle but deeply personal re-evaluation of what they wanted from their professional futures. Thirteen participants indicated that the pandemic had prompted them to reflect on their long-term goals, values, and definitions of success. This internal change often led to a reimagining of entrepreneurship, not necessarily as a fallback, but as a potential vehicle for living a life more aligned with autonomy, meaning, and flexibility.

For some, the disruption of routine and the loss of traditional academic or social milestones created space for introspection. Participant four shared: “COVID made me pause... and really think about what I want… I used to be set on corporate life, but when everything slowed down, I started questioning why… I realized I want freedom more than structure.” These narratives suggest that the pandemic functioned as a developmental breakpoint, what resilience theory might call an opportunity for “adaptive recalibration.” The shift was not merely reactive but reflective, as students used the disruption to reassess priorities and reconsider previously unquestioned career trajectories.

Eight participants said the experience changed their perception of time and work–life balance. They began to view entrepreneurship as a way to build a career on their own terms, integrating personal goals, lifestyle preferences, and professional ambition. Student 30 explained:

“(Before the pandemic) I thought success meant a job in a big firm and a busy schedule and I pictured myself in a suit, commuting, meetings all day… that’s what I thought achievement looked like… now I think success is about having time for yourself, doing something meaningful, something you actually care about… That’s where entrepreneurship started to make more sense to me… It’s not just about money anymore… it’s about building something that fits the life I want.”

(P 30)

Another student reflected similarly:

“I started thinking… what if I could work on something I love and not just something that pays well? Before COVID, that felt unrealistic, like you had to pick something practical or safe. But when everything stopped, I realized how fast things can change… Now I feel like I’d regret not trying to do something that actually matters to me… even if it’s a bit risky.”

(P19)

This movement away from external validation toward internal motivation reveals a broader reframing of aspiration. The TPB elements were visible in the shift in attitudes toward entrepreneurship. In other words, it was no longer just about profit or innovation but about aligning work with identity and personal well-being.

For others, the pandemic exposed the fragility of conventional career paths and sparked a desire to pursue goals they had previously sidelined. Five participants reported reviving old ideas for creative or community-based businesses, e.g., initiatives that had once seemed impractical but were now viewed as legitimate pursuits. Participant 27 noted: “The old plan was to play it safe… after everything that happened, I feel like if you don’t take a chance on something you care about then what’s the point?” These shifts also reflected elements of psychological resilience, not just recovery from disruption, but growth through it. Students spoke about finding clarity in chaos, reassessing their identities, and embracing uncertainty as a catalyst for personal development.

At the same time, this theme did not represent a wholesale embrace of entrepreneurship. Some participants (n = 4) said they were still unsure whether they had the resources or confidence to pursue it, even if the idea had become more appealing. In these cases, the reimagining of career paths was aspirational but still constrained by perceived external limitations, suggesting that intention had shifted, but readiness remained tentative.

6.4. Learning in Crisis and the Role of Online Education

The move to online learning during the pandemic created new conditions for how entrepreneurship was both taught and experienced. For some students, this shift was disorienting and demotivating, while for others it became an unexpected catalyst for self-driven experimentation. Ten participants expressed feelings that online education lacked the structure, support, and inspiration they previously relied on. However, eight participants said the shift gave them more flexibility to pursue entrepreneurial interests outside the classroom. This theme revealed the dual role of online learning environments acting as both a barrier and an enabler of entrepreneurial development.

Several participants (n = 17) struggled with the lack of in-person interaction and the limited ability to build networks or receive real-time feedback. Participant eight shared: “I felt like I was just… going through the motions… Without being on campus, it was hard to stay engaged… Entrepreneurship felt like this abstract concept we talked about, it didn’t feel real.” For these students, the virtual setting created a sense of disconnection, not only from instructors and peers, but from the practical, hands-on components of entrepreneurship education. In this context, learning was perceived as passive rather than active, and the reduced visibility of support systems led to lower perceived behavioral control. Some students (n = 7) expressed concern that they were being taught how to adapt to change, but were not given the tools to actually do so.

Yet this was not a universal experience. For other students (n = 12), online learning offered a different kind of autonomy, one that allowed for experimentation and application outside academic boundaries. Participants said that being away from physical classrooms gave them more time and space to explore their own ideas, take small risks, and test entrepreneurial activities in real time. Participant 15 explained: “During lockdown… I had more time, and classes were flexible… I started trying things like selling online, learning how to build a website… It wasn’t for a grade or anything… it was just me figuring it out.” Another participant described a similar shift: “The online stuff gave me weirdly more freedom… I wasn’t tied to a classroom or schedule as much… I used that time to work on a YouTube channel, mess around with drop shipping… stuff I never would’ve tried if I was stuck in normal classes.” (P9) This informal, experiential approach aligns with effectuation theory, where action begins with available means rather than pre-set goals. For these students, the crisis environment opened opportunities for creative problem-solving. Students began to engage with entrepreneurship not just as a subject, but as a process they could navigate independently.

Six participants also noted that online platforms and digital tools became central to their understanding of modern entrepreneurship. Learning about e-commerce, digital marketing, and remote collaboration during the pandemic made the entrepreneurial landscape feel more accessible, particularly for those who felt unprepared to launch a physical or traditional business. At the same time, some students expressed uncertainty. While they appreciated the freedom of online learning, they felt underprepared in areas such as pitching, building teams, or accessing funding. This tension highlights the limits of resilience; while students demonstrated adaptability, the shift also exposed inequities in digital access, motivation, and informal learning environments.

6.5. Entrepreneurial Identity in Formation

For many students, the pandemic was not just a disruption of plans, but a moment of personal transformation. Ten participants (n = 10) spoke about how their views on entrepreneurship evolved into something more personal, more reflective, and more tied to questions of identity. Rather than seeing entrepreneurship solely as a career path, they began to integrate it into their understanding of who they were, or who they were becoming. This theme captures the emotional and cognitive terrain of identity formation, where intention was shaped not only by external factors, but also by inner shifts in self-perception.

For some, the pandemic created a heightened sense of agency. Being forced to confront uncertainty at an early stage in their professional lives made entrepreneurship feel not just possible, but necessary. Participant 10 said: “I used to think of entrepreneurs as these bold, fearless people… now I feel like I could be one of them… not because I’m fearless, but because I’ve already dealt with chaos, and I know I can handle it.” This response reflects the essence of resilience theory, where adversity contributes not only to coping strategies but to identity reconstruction. The student does not simply see entrepreneurship as an option, but they begin to see themselves as someone who could embody it. This shift from external aspiration to internal alignment marks a critical stage in entrepreneurial identity development.

Seven participants described the emergence of a more tentative, evolving entrepreneurial self-concept. They had not yet started a business, and some doubted they ever would, but the idea of themselves as “someone who could” lingered. Participant 23 reflected: “I don’t know if I’ll start something soon or ever… I think differently now. I see things and wonder… could that be an opportunity… That’s new for me.” Participant 17 described this change in mindset as well: “I still don’t have a business idea or a plan. But I do feel like I think differently now. I notice gaps or problems and wonder if someone could fix that… or if I could. It’s like I have a part of me now that asks those questions.” (P17) Here, we see a subtle yet meaningful shift in mindset. What might be termed attitudinal change in the TPB is, in these cases, accompanied by early markers of identity work. Students begin to see the world through a different lens, not necessarily committing to entrepreneurship, but thinking like an entrepreneur.

Some participants (n = 5) also discussed their increased confidence in navigating ambiguity, especially after having dealt with educational disruptions, financial strain, or personal uncertainty during the pandemic. They saw entrepreneurship not as a well-defined path, but as a space where adaptability was a strength. Participant 30 explained: “There’s no single way to do it… That’s something I learned, and you can start with what you have and figure it out as you go.” This perspective aligns closely with effectuation theory, where identity is formed not through prediction, but through iterative action and self-awareness. The students who expressed this view often described small, informal experiments, side hustles, online selling, or brainstorming ideas, not as fully developed ventures, but as steps toward a self-image they were still constructing.

7. Discussion

This study explored how undergraduate business students conceptualized their entrepreneurial intentions after the pandemic. The pandemic posed a particularly complex challenge, creating significant uncertainty in job markets that rippled through to business students at universities [

12,

15]. Participants in this study recognized the challenges created by the pandemic but many also viewed the changing landscape as an opportunity to become entrepreneurs. Rather than being dissuaded by the unknown, they described becoming motivated by it, learning to be resourceful, launching side hustles, and viewing adaptability as a necessary life skill. For many, entrepreneurship was framed as a way not only to navigate future economic instability, but also to find personal fulfillment and meaning through their work.

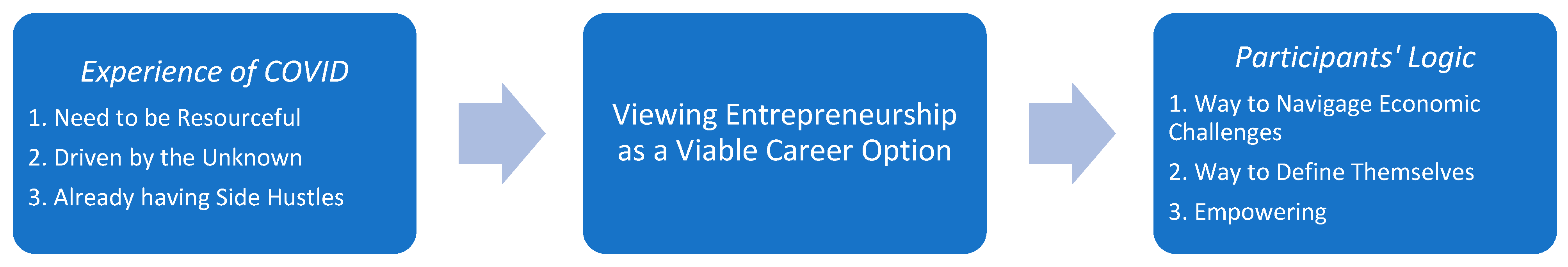

Figure 1 highlights the participants’ experiences and the logic they used to think about entrepreneurship in the post-pandemic context.

These findings must also be understood within the broader context of post-pandemic society. The COVID-19 crisis not only disrupted academic experiences but also fundamentally altered labor market dynamics, accelerated the normalization of remote work and the gig economy, and heightened cultural emphasis on self-reliance and adaptability. In this environment, students’ entrepreneurial intentions were shaped as much by personal ambition as by external conditions that made traditional career paths seem less stable and desirable. The reimagining of entrepreneurship, therefore, cannot be separated from the structural and cultural shifts triggered by the pandemic.

The participants expressed views on entrepreneurship that aligned with the TPB [

36,

42]. The economic upheaval of the pandemic diminished external incentives for entrepreneurship, such as the promise of financial gain, yet it appeared to strengthen internal motivations toward self-fulfillment and autonomy. This positive inclination toward entrepreneurship among university students is consistent with other post-pandemic research [

26,

52]. Recent studies have also found that individuals who believe in their ability to succeed in a business venture are more likely to express entrepreneurial intentions [

53]. Considering that these participants were based in the U.S., a context that culturally emphasizes independence and self-initiative, it is possible that they demonstrated particularly strong entrepreneurial orientations.

The results also highlighted that several participants demonstrated entrepreneurial qualities associated with effectuation theory. They emphasized the importance of adaptability, flexibility, and experimentation, particularly in response to economic challenges. Participants most readily modeled the Bird-in-Hand principle of effectuation [

35], focusing on what they had, e.g., skills, time, and access to digital platforms, rather than what they lacked. Given the age and experiences of the participants, this is unsurprising; many had not yet developed the networks, partnerships, or capital required to fully engage with other effectual principles, such as Affordable Loss, Crazy Quilt, or the Lemonade Principle. Participants did not describe significant barriers to applying effectual logic [

54,

55]; rather, they acknowledged and adapted to the realities of their context. Although this study did not examine the formal application of effectuation principles in educational settings, research on student-based entrepreneurial project learning has found significant variation in students’ ability to apply these principles systematically [

56]. Nonetheless, the participants’ effectual mindsets suggest a willingness to problem-solve and innovate in the face of uncertainty.

The participants’ experiences during the pandemic also fostered a mentality of resilience [

29]. Many described embracing challenges and finding ways to adapt rather than retreat. They acknowledged the importance of coping with uncertainty, recognizing that perseverance would be critical for success in future entrepreneurial endeavors. Resilience has become a key concept in contemporary entrepreneurship research, with a growing body of literature examining how entrepreneurs navigate adversity [

57,

58]. For example, a study of Indonesian businesses identified three stages in the resilience process: resilience awareness, adaptation, and action [

59]. While the current study focused on undergraduate students rather than established business owners, the comparison offers a useful framing. The participants demonstrated strong resilience awareness and some adaptation strategies, even if they were not yet positioned to act fully on entrepreneurial ventures. This suggests that, developmentally, they are progressing through similar stages of resilience formation, laying a foundation for future entrepreneurial behavior once they transition into post-graduation environments.

To synthesize how the three theoretical frameworks align with the participants’ responses,

Table 1 provides a comparative summary of key findings mapped across the constructs of the TPB, effectuation theory, and resilience theory.

While each theoretical lens offers a distinct perspective, the findings also suggest points of convergence across TPB, effectuation, and resilience theory. For example, students who reframed entrepreneurship as a means of control during the pandemic expressed both a strong sense of perceived behavioral control (TPB) and a willingness to act with limited resources (effectuation), often grounded in adaptive coping mechanisms (resilience theory). This overlap reinforces the idea that entrepreneurial intention in crisis contexts is shaped not just by cognitive assessment, but also by emotional resilience and flexible action strategies. These intersections are reflected in

Table 1 and help contextualize students’ responses as multi-dimensional rather than theory-bound.

It is important to contextualize these findings within the broader generational characteristics of the participants. As university students currently completing their undergraduate degrees, the participants can be identified as members of Generation Z, a cohort that has grown up in an era of rapid technological advancement, economic instability, and social change [

60]. Literature suggests that younger generations may approach entrepreneurship not merely as a means of economic advancement but also as a pathway to achieving autonomy, flexibility, and alignment with personal values [

29,

61]. In this respect, it is difficult to isolate the pandemic as the sole factor influencing their entrepreneurial thinking. Instead, it is plausible that the participants’ responses reflect a broader generational orientation that embraces entrepreneurial activity as part of a lifestyle strategy. This interpretation is supported by the emphasis participants placed on informal ventures and the appeal of “side hustles,” which may be viewed not only as responses to crisis, but also as expressions of generational identity and preference for self-directed professional development [

30,

33]. Future studies may wish to explore to what extent such traits are specific to Generation Z, or whether they reflect broader trends in post-pandemic career attitudes.

The findings of this study also point toward future avenues for research and teaching. Participants discussed the role of side hustles in shaping their entrepreneurial aspirations, suggesting that informal business activities during the pandemic may have acted as early stepping stones toward more formal entrepreneurial ventures. Although there is some emerging research examining side hustles broadly [

61,

62], further studies are needed to explore how college students view side hustles as part of their entrepreneurial identity, particularly in a post-pandemic context. In addition, there are opportunities for entrepreneurship education to integrate the gig economy into classroom learning. Future research could examine how experiential learning models, such as side hustle projects or gig work simulations, might enhance entrepreneurial readiness and bridge the gap between theory and practice for undergraduate students.

8. Conclusions

This study set out to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate business students. The findings revealed a complex interplay of factors. For some participants, entrepreneurship emerged as a means of reclaiming agency and creating stability in an unpredictable world. Others approached the idea of entrepreneurship with increased caution, recalibrating their career ambitions in response to heightened perceptions of risk and vulnerability. The disruption also prompted a broader re-evaluation of professional goals and success, leading many to prioritize autonomy, personal fulfillment, and work–life balance over traditional employment pathways. Meanwhile, the shift to online education shaped these experiences in uneven ways, with some students finding greater independence to pursue entrepreneurial ideas, and others feeling disconnected from hands-on learning opportunities. Across these variations, a common thread emerged: the gradual formation of entrepreneurial identities shaped not solely by ambition, but by resilience and adaptability.

These insights carry important implications for the field of entrepreneurship education. They suggest that entrepreneurial intention is not a fixed characteristic, but a dynamic process shaped by crisis, reflection, and identity development. There is a growing need for curricula that emphasize flexibility, experimentation, and resilience, particularly through pedagogical strategies such as experiential learning, scenario-based crisis simulations, and the integration of digital entrepreneurial tools. Educators should also consider embedding reflective practices and identity-focused discussions to help students explore how personal values and life goals intersect with entrepreneurial pathways. These approaches can create learning environments that prepare students not only to write business plans, but to adapt creatively and think critically in real-world uncertainty.

Beyond educational implications, this study offers insight into entrepreneurial support ecosystems and policy design. As students increasingly view entrepreneurship as a pathway to purpose, autonomy, and resilience support structures must evolve accordingly. Incubators, mentorship programs, and seed funding initiatives may need to adopt more inclusive models that support non-traditional, values-driven ventures and offer scaffolding for emotionally and experientially diverse founders. Policymakers should also recognize that younger generations entering the workforce may prioritize flexibility, remote work, and mission-aligned entrepreneurship over linear employment tracks. To meet these evolving aspirations, institutional support should combine financial and technical resources with mentoring, mental health services, and flexible funding that reflects the nonlinear path of entrepreneurial growth. It is important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. As with all qualitative research, generalization is not the intent or within the possibility of the study. First, the participant sample was drawn from a single public university in the Midwestern United States, which constrains the transferability of the findings to other institutional or cultural contexts. Second, as with most qualitative research, the data reflect self-reported perceptions rather than observed behaviors, which limits the ability to infer how expressed intentions may translate into entrepreneurial action. While intention is commonly understood to be a strong predictor of behavior [

36,

42], the actualization of these intentions remains unexamined within the scope of this study. Third, participants were self-selected into the study, potentially skewing the sample toward individuals already reflective or entrepreneurially inclined. Finally, the study captures a moment in time during which the COVID-19 crisis remained salient in participants’ academic and personal lives. Longitudinal research is required to assess the stability of these entrepreneurial orientations as students transition into post-pandemic economic and social environments. While this study focused specifically on the COVID-19 pandemic, it is worth noting that past economic crises, such as the 2008 financial collapse, have also triggered surges in entrepreneurial activity, though often in response to financial necessity rather than personal transformation. What distinguishes the pandemic context is its simultaneous disruption of education, employment, and identity development. For educators and policymakers, the findings highlight the need for entrepreneurship education that fosters resilience, values-driven thinking, and context-sensitive decision-making.