1. Introduction

COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, marking the onset of a global pandemic [

1]. Initially characterized primarily as a respiratory infection, subsequent investigations have demonstrated that COVID-19’s impact extends beyond the respiratory system. Research has indicated that the virus can infiltrate the central nervous system (CNS), leading to a range of neuropsychiatric and neurological complications [

2]. The spectrum of neuropsychiatric manifestations associated with COVID-19 is significant. A meta-analysis encompassing 27 studies revealed alarming prevalence rates for various mental health disorders among COVID-19 survivors. Specifically, the rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, psychological distress, depression, and sleep disorders were found to be 20%, 22%, 36%, 21%, and 35%, respectively, based on a cohort of 9605 individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 [

3].

Cognitive impairment and psychopathological symptoms have been documented in patients recovering from the acute phase of COVID-19 [

4,

5]. Research indicates that these negative effects may persist over time. For instance, a study revealed that COVID-19 patients exhibited declining performance in reaction time tasks, alongside lower mental health scores and higher fatigue indices, extending beyond two years post recovery [

6]. Furthermore, these adverse effects are not limited to older populations; they can also impact younger individuals. A study focusing on young university students demonstrated that 39 months after recovery, both the infection itself and its severity had detrimental effects on their overall health. Additionally, there was a negative correlation observed between the severity of COVID-19 and cognitive performance among these students [

7]. Research has identified brain structural changes, neuroinflammation, and viral invasiveness as potential contributors to long-term neurological and mental health adversities associated with these infections [

8]. Furthermore, more recent evidence suggests that the adverse effects can last for more than four years following the initial infection [

9,

10].

As already mentioned, emerging research suggests that COVID-19 survivors in this young age group may be vulnerable to long-term mental health consequences, but studies focusing specifically on mild-to-moderate COVID-19 cases in university populations remain scarce. Understanding how disease severity, time since infection, and sex influence psychological outcomes in this population is crucial for identifying at-risk individuals and designing targeted mental health interventions. Additionally, prior studies have often lacked validated psychometric assessments for evaluating long-term psychological distress or have overlooked it altogether (e.g., [

10,

11]). Many investigations into post-COVID-19 mental health have relied on self-reported symptoms without using standardized tools, making it difficult to compare findings across studies (e.g., [

6]). The present study addresses this gap by employing the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), a widely recognized instrument for assessing psychopathology. Furthermore, while sex differences in acute COVID-19 outcomes have been well documented, less is known about how sex influences long-term mental health effects in young adults, despite evidence that women may be at greater risk for persistent symptoms due to immune system differences and hormonal influences [

12].

Given these gaps, the present study aims to investigate the relationship between COVID-19 severity, time since infection, and sex in relation to mental health outcomes among university students. By focusing on a younger, non-hospitalized population, this research will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of long COVID’s impact on mental health across different demographic groups. Additionally, the findings will provide actionable insights for universities and mental health professionals to develop targeted post-COVID-19 interventions tailored to young adults.

Based on these considerations, it was hypothesized that a longer time since COVID-19 infection would correlate with higher scores on the SCL-90-R scales among participants. Additionally, it was posited that greater severity of the infection would be associated with elevated scores on the SCL-90-R scales. Furthermore, it was hypothesized that female participants with a history of COVID-19 would experience more significant mental health challenges compared to their male counterparts who also had prior COVID-19 infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 346 students from Bu-Ali Sina University volunteered to participate in this cross-sectional study. Participants were approached on the university campus and invited to engage in research focused on individuals with a history of either mild or moderate COVID-19. Specifically, mild cases were defined as those who had recovered at home without requiring medical intervention, while moderate cases included individuals who had received medical care at outpatient clinics.

Bu-Ali Sina University, located in Hamadan, in the Central District of Hamadan County in Hamadan province in western Iran, is a public institution that boasts a diverse student population. The university has a significant alumni base, with over 60,000 alumni and more than 10,000 active students at the moment, offering a wide range of programs in various fields, including humanities and social sciences, sciences, engineering sciences, and veterinary medical sciences. The university primarily serves young adults from different regions of Iran, a demographic known for its youthful characteristics, such as overall good physical and mental health, enthusiasm for learning, adaptability to new environments, and engagement in community activities that foster personal growth and academic success.

Out of the initial cohort, 41 participants were excluded from this study due to incomplete data or pre-existing mental health disorders and also medical conditions known to affect mental health, such as hyperthyroidism. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 305 subjects who met the inclusion criteria and participated in this study.

A sample size of 305 is robust for the statistical tests employed in this study. For multivariate analyses, methodological guidelines typically recommend a minimum of 200 participants to ensure stable estimation of covariance matrices and to reliably detect moderate effect sizes (see [

13]). Similarly, ANCOVA requires approximately 20–30 participants per subgroup to yield reliable estimates (see [

14]); the sample of this study provided adequate numbers across sex and COVID-19 severity groups, ensuring balanced comparisons. More importantly, non-parametric methods like partial Kendall’s Tau method, which was used to validate the findings of the MANCOVA and ANCOVA tests, are known to be robust even with moderate sample sizes, and the current sample exceeds the common thresholds for these analyses in mental health research.

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected in person through the administration of the “Symptom Checklist-90-Revised” (SCL-90-R) to the participants. Each participant received comprehensive information regarding this study, including its objectives and significance. Based on the questionnaire’s manual, instructions were provided to ensure that participants could accurately complete the checklist [

15].

Before participating in this research, all respondents were assured of their anonymity, and voluntary informed consent was obtained from each individual. Participants were informed about the scope of this study, its objectives, and the fact that the findings would be published as an article in a scientific journal. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from this study at any time without facing any conditions or consequences.

The ethical conduct of this research adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Instrument

The instrument utilized in this study was the Farsi version of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R). This self-report questionnaire comprises 90 items, each rated on a five-point Likert scale, where responses range from 0 (“None”) to 4 (“Extreme”). The SCL-90-R is in part structured around nine primary symptom dimensions: Somatization (SOM), Obsessive-Compulsive (O-C), Interpersonal Sensitivity (INS), Depression (DEP), Anxiety (ANX), Hostility (HOS), Phobic Anxiety (PHO), Paranoid Ideation (PAR), and Psychoticism (PSY) [

16].

The Farsi version of the SCL-90-R used in this study was a contextualized and validated adaptation of the original instrument for use in the Iranian population. Its psychometric properties were assessed in previous research, demonstrating satisfactory characteristics in the Iranian population. The reported Cronbach’s alpha values for its subscales ranged from 0.76 to 0.88, with an overall coefficient of 0.97, confirming its reliability in assessing psychological distress in this context (see [

17]). Given these properties, the Farsi SCL-90-R, as an appropriate tool for evaluating mental health in Iranian university students, was utilized in this study.

2.4. Data Analysis

R (version 4.2.0) and SPSS (SPSS Statistics V26, IBM) were utilized for the analysis of the data collected in this study. Descriptive statistics were computed to provide a comprehensive overview of the sample characteristics. To explore potential differences between participants based on sex and severity of COVID-19, crosstabulation methods were employed.

Subsequently, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA), controlled for age, was performed to determine whether any independent variables or their interactions could significantly forecast the respondents’ scores on the dependent variables. Following the MANCOVA, univariate models of covariance (ANCOVA), controlled for age, were examined for each independent variable and their interactions to assess their possible effects on each dependent variable.

Given concerns regarding normality and homogeneity of variances, which were revealed through the descriptive analysis and the Levene’s test, which assesses the assumption of equality of error variances, the partial Kendall’s Tau correlational analysis, a non-parametric multivariate analysis method, was employed, stratified by sex and controlled for age. These non-parametric tests served to validate whether or not the findings from parametric tests remained robust when the data did not follow a Gaussian distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistical analysis revealed that the participants had an average age of 22.80 years and a mean duration of 15.18 months since infection. Among the psychological measures assessed, the depression scale exhibited the highest mean score (15.90), followed by somatization (14.01). In contrast, the phobic anxiety scale recorded the lowest mean score (3.95) (

Table 1). Crosstabulation analysis revealed that among the women included in this study (total n = 156), 53.8% (n = 84) had experienced a mild case of COVID-19, while 46.2% (n = 72) had encountered its moderate form. For men (total n = 149), the analysis showed that 57.7% (n = 86) had experienced mild COVID-19, whereas 42.3% (n = 63) had experienced its moderate form. When examining the distribution of mild cases across these two sexes (total n = 170), it was observed that 49.4% (n = 86) were men, and 50.6% (n = 84) were women. For moderate cases (total n = 135), the proportions shifted slightly, with 53.3% (n = 72) being women and 47.7% (n = 63) being men. The chi-square test conducted to evaluate these differences did not yield statistically significant results (χ

2(1) = 0.463,

p = 0.496).

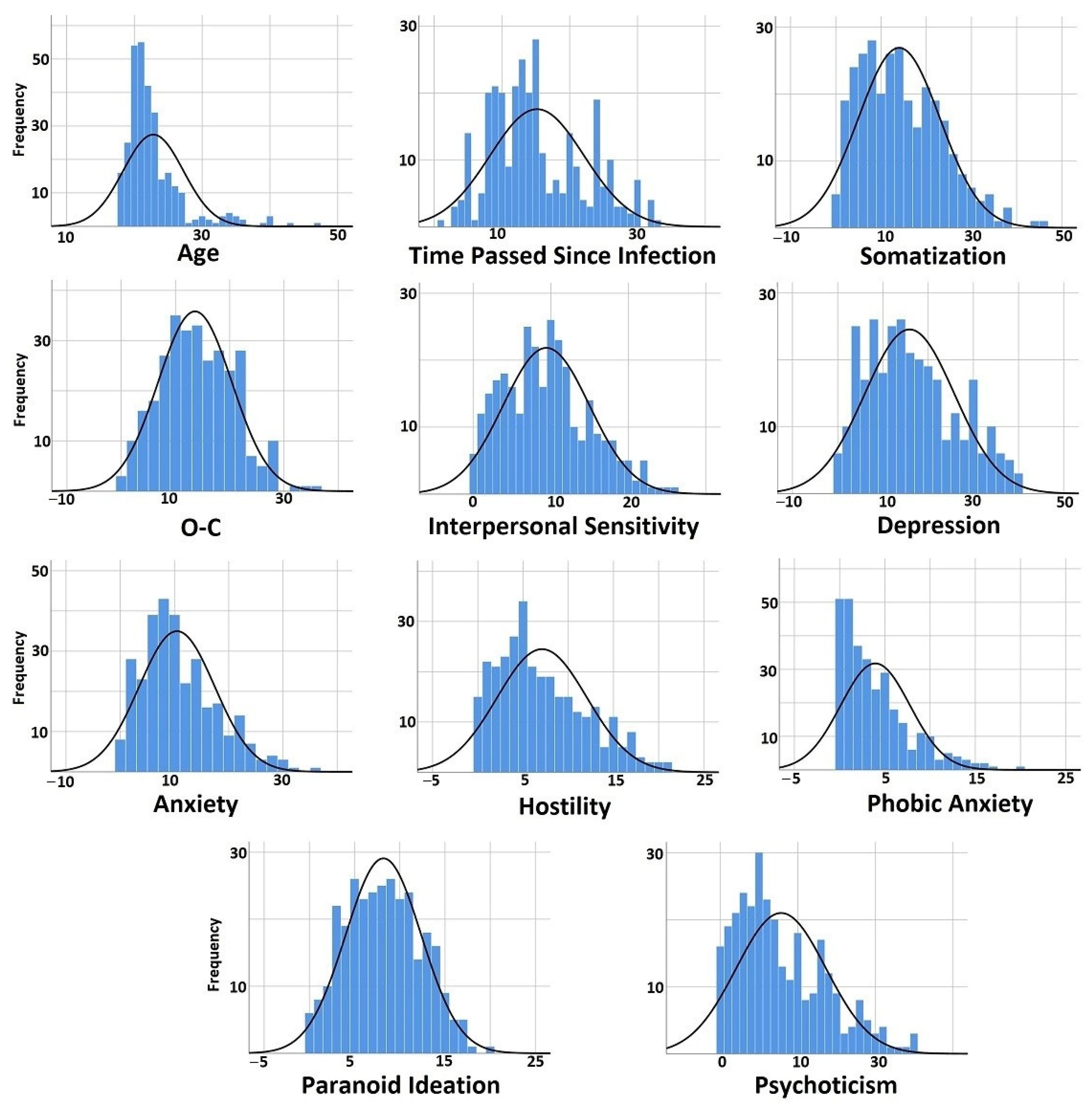

In addition, an examination of the skewness values and histograms of the dataset indicated that the distributions did not conform to a Gaussian model (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

3.2. MANCOVA Results

To elucidate the potential effects of the independent variables on the dependent variables, a MANCOVA was conducted, controlling for age as a covariate.

The results showed that two models were statistically significant. The first model identified the time passed since COVID-19 infection (TSI) as a significant independent variable, with F

(270, 1845) = 1.197,

p = 0.022, and a partial eta-squared value of 0.149, suggesting a moderate effect size. The second model demonstrated that sex was also a significant independent variable, with F

(9, 197) = 2.442,

p = 0.012, and a partial eta-squared value of 0.100, indicating a small-to-moderate effect size. However, none of the other independent variables or their interactions reached statistical significance (

Table 2).

3.3. ANCOVA Results

To further explore these findings, ANCOVA models for each dependent variable were constructed to identify which independent variables had a statistically significant impact on the dependent variables under consideration (

Table S1). The findings demonstrated that sex had a statistically significant effect on somatization (F

(1) = 10.186,

p = 0.002, partial η

2 = 0.047), which suggests that differences in somatization symptoms are influenced by sex, with a moderate effect size.

The duration of time elapsed since infection significantly affected several psychological dimensions. Specifically, it had a notable impact on interpersonal sensitivity (F(30) = 1.529, p = 0.046, partial η2 = 0.183), depression (F(30) = 1.939, p = 0.004, partial η2 = 0.221), and anxiety (F(30) = 1.829, p = 0.008, partial η2 = 0.211), which indicates that this variable plays a role in shaping these psychological outcomes, with large effect sizes observed for depression and anxiety in particular. Additionally, its influence on O-C approached statistical significance (F(30) = 1.492, p = 0.057, partial η2 = 0.179), suggesting a potential trend.

The severity of COVID-19 was found to significantly affect multiple psychological variables. It had a significant impact on somatization (F(1) = 6.277, p = 0.013, partial η2 = 0.030), O-C (F(1) = 3.942, p = 0.048, partial η2 = 0.019), and anxiety (F(1) = 4.866, p = 0.028, partial η2 = 0.023); the effect sizes were small to moderate for these variables. Furthermore, the severity of COVID-19 showed an almost significant relationship with psychoticism scores (F(1) = 3.825, p = 0.052, partial η2 = 0.018). While this result did not reach conventional thresholds for statistical significance (p < 0.05), it indicates a possible association trend between disease severity and psychoticism.

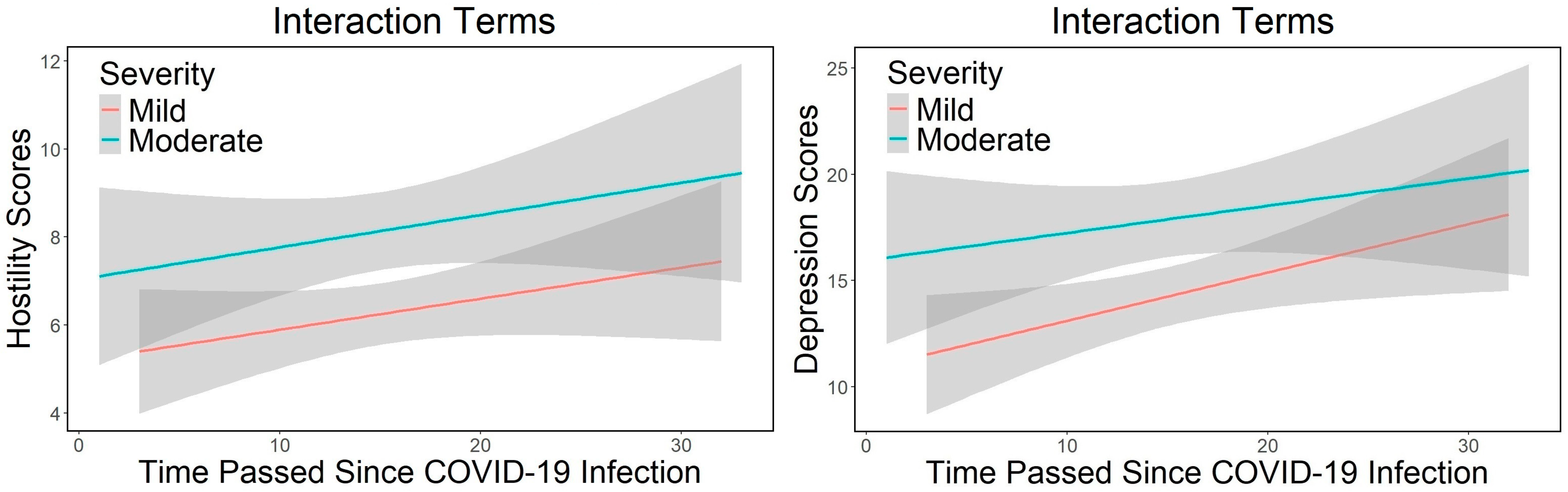

Further examination of the statistical models revealed that the interaction between the duration of time since infection and the severity of the disease was statistically significant for depression (F

(26) = 2.158,

p = 0.002, partial η

2 = 0.215) and hostility (F

(26) = 1.578,

p = 0.043, partial η

2 = 0.167). The interaction plots for the examined variables indicated that the interaction effect was more pronounced and obvious for depression than for hostility (

Figure 2). The depression scores were consistently lower in mild cases compared to moderate cases; however, there was a notable increase in depression scores over time since infection, particularly from month 10 onwards. This increase was steeper in mild cases when compared to moderate cases. In contrast, hostility scores displayed a relatively stable gradient of increase over time, with the interaction effect being prominently less obvious.

3.4. Partial Kendall’s Tau Results

To validate the aforementioned findings, a multivariate non-parametric test known as the partial Kendall’s Tau correlational method was utilized. This statistical method was employed to examine whether the observed results remained consistent when analyzed within a non-parametric framework. The use of partial Kendall’s Tau is particularly advantageous in scenarios where the assumptions of parametric tests may not be met, allowing for a robust assessment of the relationships among multiple variables without relying on normality or the homogeneity of variances. In addition, it allows researchers to analyze associations between binary, ordinal, and continuous variables. The application of this test involved calculating the partial correlation coefficients that quantify the strength and direction of associations between the independent and dependent variables while controlling for age.

3.4.1. All Participants

For all participants, regardless of their sex, the findings indicated that there were positive and statistically significant correlations between age and O-C. Additionally, a positive and significant relationship was observed between the time since COVID-19 infection and various scales, including O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, and paranoid ideation. Furthermore, the severity of COVID-19 infection demonstrated significant positive correlations with somatization, O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Lastly, sex was found to have a negative and significant correlation with somatization, O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, and anxiety. It is important to note that in this study, men were coded as 1 and women as -1; thus, the negative correlation associated with sex suggests that women exhibited higher scores on these scales compared to men (

Table 3).

3.4.2. Men

Amongst men, it was found that the time since the initial infection was positively and significantly correlated with levels of hostility. The positive correlation indicates that as the time since the initial COVID-19 infection increases, the levels of hostility among men also tended to increase. Furthermore, the severity of the COVID-19 infection exhibited significant positive correlations with various scales, including somatization, O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. These imply that individuals who experienced more severe symptoms during their illness were likely to report higher levels of psychological distress across multiple dimensions (

Table 3).

3.4.3. Women

For women, the duration of time elapsed since infection with the virus exhibited a significant positive correlation with interpersonal sensitivity, depression, and anxiety. This means that as the time since infection increased, women tended to experience higher levels of sensitivity in their interactions with others, along with increased feelings of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, the severity of the COVID-19 infection was also significantly and positively correlated with various scales, including somatization, O-C, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. This suggests that individuals experiencing more severe COVID-19 symptoms reported higher scores on these scales (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study examined the influence of the time since COVID-19 infection (TSI), the severity of the infection, and sex, while controlling for age, among university students who experienced mild-to-moderate courses of COVID-19.

The present study confirmed the following hypotheses: a longer time since COVID-19 infection correlates with higher scores on the SCL-90-R scales among participants; greater severity of the infection is associated with elevated scores on the SCL-90-R scales; and female participants with a history of COVID-19 experience more significant mental health challenges compared to their male counterparts who also had prior COVID-19 infections. These findings will be elaborated on in detail in the following subsections.

4.1. Sex

The results from the MANCOVA indicated that sex had statistically significant associations with the scales of the SCL-90-R. Furthermore, the ANCOVA revealed that sex significantly affected somatization. To explore these relationships further, partial Kendall’s Tau correlations demonstrated a negative association between sex and somatization. When considering the coding for sex (−1 for women and 1 for men), this finding suggested that there was a correlation indicating higher somatization scores among women relative to men. Additionally, partial correlational analysis indicated that there were significant correlations between being a woman and higher levels of O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, and anxiety compared to being a man.

These findings align with previous research indicating that COVID-19 infection is correlated with more severe acute inflammatory symptoms in men, whereas women tend to exhibit long-term symptoms associated with autoimmune responses. For instance, in this regard, the increased expression of XIST, an RNA gene linked to autoimmunity during infection in women [

12], involving neurological complications [

18], has been suggested as the underlying causal link. Other factors, such as psychobiological elements, also appear to mediate these associations more significantly in women; a prominent example of this is depression [

19].

Given these sex-specific vulnerabilities, targeted interventions—such as campus-based mental health screenings, counseling tailored to post-COVID-19 symptoms, and support groups for long-haul COVID-19 survivors—are crucial. Addressing these disparities will ensure that women recovering from COVID-19 receive the necessary mental health support, ultimately promoting better academic performance and emotional well-being.

4.2. Time Passed Since COVID-19 Infection (TSI)

There was a significant interaction between the TSI and the severity of COVID-19 infection concerning depression and hostility. In terms of depression, the findings suggested that as the TSI increased, there was a more pronounced increase in depression scores among individuals with mild cases compared to those with moderate cases. However, it is noteworthy that overall depression scores remained higher for individuals with a history of moderate COVID-19 infection. In relation to this finding, individuals who have experienced moderate cases of illness may develop resilience through coping strategies that they acquire during and after their immediate recovery. Furthermore, they are likely to receive increased support from others, particularly family members, throughout and following their illness, which could alleviate long-term effects and result in a less significant rise in depression levels. It is also likely that individuals with more severe cases may experience positive transformations, such as post-traumatic growth, which could also affect outcomes; however, this explanation is considered less likely compared to the previously mentioned factors since it can be argued that those with moderate cases did not endure a severe manifestation of the disease, which is more probable to result in post-traumatic growth. Regarding hostility, while the overall scores were higher for moderate cases, the interaction effect was less pronounced compared to that observed for depression.

Furthermore, partial Kendall’s Tau correlations indicated that as the TSI increased, the scores for O-C symptoms, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, and paranoid ideation also exhibited an upward trend. A separate analysis of these associations by sex revealed that with increasing TSI, men’s scores in hostility rose, while women’s scores in interpersonal sensitivity, depression, and anxiety increased. These findings align with the existing literature suggesting that mental health deterioration along the trajectory of time elapsed since COVID-19 infection is observed in patients with a history of COVID-19 infection [

10,

20,

21]. Furthermore, the current study demonstrates that these associations are more prevalent in women than in men. This finding is consistent with previous research [

22].

The persistent effects of COVID-19 beyond the acute phase of infection are believed to arise from several factors, including the persistence of SARS-CoV-2, direct damage to organs, disturbances in both the innate and adaptive immune systems, autoimmunity, the reactivation of latent viruses, endothelial dysfunction, and alterations in the microbiome (for a comprehensive review, see [

23]).

Variations in associations related to sex, concerning the relationships between the TSI and the above-mentioned scales, may stem from a range of influences. These include pathophysiological differences between men and women concerning COVID-19 infection [

12] and psychological disparities between individuals experiencing long COVID and those who do not [

24], as well as the sociocultural determinants that affect these outcomes [

25].

While much attention has been given to older or hospitalized patients, the findings of the present study indicate that even mild-to-moderate infections can lead to persistent psychological distress in university students, affecting depression, anxiety, hostility, and O-C symptoms over time. Given that college students may already face psychological distress due to academic pressure and, potentially, social challenges, these results underscore the need for post-COVID-19 mental health interventions on campuses.

The existing literature suggests that young adults are vulnerable to post-viral neuropsychiatric symptoms, including those following SARS-CoV-2 infections [

6,

10,

20]. Recognizing these long-term effects is essential for developing targeted mental health policies, such as routine screenings, counseling services, and university-led wellness programs. Addressing these concerns can likely prevent academic disruptions, impaired social functioning, and long-term psychiatric complications among young COVID-19 survivors.

4.3. Severity of COVID-19 Infection

The findings indicate that the severity of COVID-19 is significantly associated with somatization, O-C, and anxiety. This observation aligns with previous research suggesting that the severity of COVID-19 infection may be a contributing factor to long COVID [

7,

26]. The robust results obtained from the partial Kendall’s Tau correlation analysis demonstrated a significant association between COVID-19 severity and various scales, including somatization, O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. These findings contribute to the expanding literature on the long-term mental health effects of COVID-19 and highlight the need for ongoing mental health support for individuals recovering from the virus, even in non-hospitalized cases.

Separate analyses for men revealed similar associations; however, the correlation with phobic anxiety was not observed. For women, the results were largely consistent with those of men. Nonetheless, in addition to phobic anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity did not show a significant correlation among women. These findings corroborate the existing literature that has identified a relationship between the severity of COVID-19 and psychiatric outcomes associated with long COVID (e.g., [

11,

27]). The observation that women demonstrated higher overall scores for psychological distress but lacked a strong association between COVID-19 severity and interpersonal sensitivity suggests that other factors, such as social support networks and coping strategies, may influence these outcomes.

The observed effects are likely attributed to anatomical damage and neuroinflammation [

28], as well as the dysregulation of neurotransmitters, with a particular emphasis on serotonin [

29]. This finding adds to the growing evidence that COVID-19 severity is an important predictor of long-term psychological distress, even among young, otherwise healthy individuals. Given that young adult university students represent a population at risk for COVID-19 post-recovery health concerns [

6,

10], these findings emphasize the need for longitudinal studies, university-based interventions, and broader public health strategies to address the long-term mental health consequences of COVID-19.

4.4. Strengths

This study involved 305 participants, which provides a relatively large sample size. A large sample size can enhance the reliability and generalizability of the results. In addition, the inclusion of multiple independent variables (TSI, severity of COVID-19, and sex) allowed for a relatively comprehensive examination of factors that might be associated with mental health outcomes as measured by the SCL-90-R, which is a well-established assessment tool. Utilizing a validated instrument lends credibility to the findings and allows for comparisons with other studies in the field.

By employing non-parametric partial Kendall’s Tau to check the results, it became possible to take steps to validate the findings against potential violations of parametric test assumptions, adding robustness to the conclusions.

Targeting university students offered valuable insights into a specific demographic relatively understudied in long-COVID research. This group is characterized by being young, generally healthy, and less likely to have experienced severe COVID-19 compared to older age cohorts.

4.5. Limitations

As a cross-sectional study, this study captured data at one point in time, making it challenging to establish temporal relationships between independent and dependent variables. In this sense, longitudinal studies would be more effective in assessing changes over time and establishing causality. Accordingly, the findings in this article are presented in terms of associations rather than causal relationships.

The reliance on self-reported measures from participants can introduce bias due to social desirability or recall bias; however, ensuring anonymity during the completion of the questionnaire should have helped to mitigate this limitation to a large degree. Furthermore, self-reported surveys represent a widely accepted, cost-effective, and accessible methodology employed in mental health research involving large sample sizes.

The absence of a control group (individuals without a history of COVID-19) limited the ability to draw causal inferences about the effects of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes, to determine whether observed effects are specifically attributable to COVID-19 or other confounding factors. Accordingly, the interpretations and conclusions of the findings presented in this article are framed in terms of associations rather than causal relationships.

The recruitment of participants from a university campus may restrict the generalizability of the findings beyond this particular demographic group. However, this study was deliberately designed to focus on this often-overlooked cohort, exploring the relationships between COVID-19 infection and its long-term impacts on mental health in young adults.

Although age was controlled for in the analyses, participants with pre-existing mental or physical health conditions were excluded, and the homogeneity of the cohort may have provided a similar contextual background for all participants, it remains possible that unknown confounding factors could have influenced the results independently of the COVID-19 infection history. Research in the human and social sciences is vulnerable to confounding variables, in contrast to experimental natural sciences that are conducted under rigorously controlled laboratory conditions. However, it is also crucial to acknowledge that these confounding effects can be largely mitigated through careful study design. This includes controlling for confounding variables, filtering participants, and incorporating relevant independent variables into the study, as was attempted in the current research.

5. Conclusions

The investigation of the long-term effects of COVID-19 is an emerging area in health sciences, emphasizing the need to monitor vulnerable populations for persistent mental health challenges. While much research has focused on older adults and hospitalized patients, the present study highlights that young adults, particularly university students, also experience prolonged psychological distress post infection. The findings demonstrate that COVID-19 severity and time since infection are significantly associated with higher scores on multiple SCL-90-R scales, with women exhibiting greater susceptibility to long-term mental health complications than men. These results underscore the importance of recognizing sex, disease severity, and time since infection as critical risk factors in post-COVID-19 mental health assessments.

Given these findings, future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to track the trajectory of psychological symptoms over time, as well as investigations into the biological and psychosocial factors driving sex differences in long-COVID mental health outcomes. Additionally, comparative studies between COVID-19 survivors and non-infected individuals could help distinguish direct viral effects from broader pandemic-related stressors. Further investigation can be conducted by incorporating the specific variants of the virus. For instance, further analysis could focus on the dominant variants present during different pandemic waves, taking into account the individual’s date of infection and geographic demographics.

From a practical perspective, universities and healthcare providers should implement targeted interventions, including routine mental health screenings, post-COVID-19 counseling programs, and tailored support groups for at-risk individuals. Developing sex-specific mental health strategies, particularly for women, also seems essential to address the long-term psychological burden of COVID-19. By integrating these approaches, institutions can reduce long-term mental health complications and improve overall well-being in young adults post recovery from COVID-19.