Abstract

The transition to a Circular Economy (CE) is a fundamental response to contemporary environmental and economic challenges. Sustainable human resource management (SHRM) is pivotal in equipping the workforce with green skills, reskilling strategies, and fostering organisational sustainability. This study undertakes a comparative analysis of Portugal and Sweden to examine the influence of SHRM strategies on CE adoption. Utilising Eurostat data and employing statistical analyses, the study assesses workforce training, circular material use, and green employment growth in both countries. The findings reveal that Sweden exhibits considerably higher engagement in workforce training (32.26% vs. 10.87% in Portugal), more prevalent circular material use (7.73% vs. 2.31%), and more consistent green job growth (higher R2 in regression models). These findings underscore the pivotal role of well-designed public policies and SHRM strategies in fostering CE adoption, underscoring their alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDGs 8 and 12. The insights derived from this study are of significance for policymakers and organisations seeking to enhance workforce sustainability and circular business models.

1. Introduction

The transition to a Circular Economy (CE) has been the subject of extensive debate, with many considering it to be one of the primary solutions to the contemporary environmental and economic challenges faced by society. The CE concept, which has been extensively promoted by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [1], proposes an economic model based on cycles with regenerative concerns that minimise waste and maximise the reuse of resources. In this context, sustainable human resource management (SHRM) emerges as a pivotal component for the success of the CE, as it fosters the training of professionals in green skills, retraining and sustainable organisational development [2].

The evolution of CE policies has been influenced by the necessity for global sustainability frameworks, including the European Green Deal, the Paris Agreement, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [3,4,5,6]. Glavič [7] defends that these novel frameworks underscore the imperative for systemic transformations in production and consumption patterns to enhance sustainability and reduce environmental impact. Leading countries such as Germany and the Netherlands have established comprehensive CE policies, emphasising extended producer responsibility, the regulation of material efficiency, and incentives for circular business models [8,9].

Conversely, a growing collaborative effort is underway among various institutions, including government agencies, companies, universities, and civil society, to adopt a CE [10,11]. Notably, public–private partnerships have been instrumental in promoting innovation, orienting education towards sustainability in response to mounting labour market and consumer demands and facilitating knowledge transfer between industries [12,13,14,15,16]. The successful implementation of a CE necessitates not only regulatory support, but also a transformation in business culture, facilitated by sustainability leadership and cross-sector collaborations, consolidated in demands from more educated and informed consumers [17,18].

While Sweden is often cited as a global benchmark in environmental policies and sustainable development [19], Portugal has made progress, but still faces structural challenges to implement business practices fully aligned with the CE [20]. Consequently, a comparative analysis of the approaches adopted by these countries can offer valuable insights to enhance SHRM practices in Portugal.

In this context, the selection of Portugal and Sweden as the focus of this study is indicative of the divergent approaches adopted by these nations in their respective policies on the Circular Economy and sustainable human resource management. Sweden is widely regarded as a global exemplar of ecological transition, a reputation attributable to its robust regulatory framework and its systematic encouragement of professional training. By contrast, Portugal continues to grapple with substantial structural impediments to the implementation of sustainable practices, despite recent advancements. The juxtaposition of these two nations offers invaluable insights for the development of public and business policies that can facilitate the adoption of the CE in diverse socio-economic contexts.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Circular Economy and Human Resource Management

The CE necessitates substantial modifications in the way companies oversee and delineate their production processes, in addition to their human resources [21]. As Geissdoerfer et al. [22] assert, the transition to a CE demands not only the integration of novel technologies, but also a shift in mindset and the cultivation of the workforce’s capabilities to engage with sustainable production processes. In this context, HRM practices assume a pivotal role in nurturing and retaining talent with competencies aligned with the CE [23].

Research findings indicate that companies predominantly align HRM with prevailing corporate structures, encountering impediments such as employee resistance, an absence of standardised metrics, and a discordance between corporate and government sustainability objectives [24,25]. This study aims to address these gaps by examining the role of HRM in overcoming such barriers in Portugal and Sweden.

The contemporary literature underscores the significance of human resource development (HRD), emphasising its integration with the concept of intra-organisational green careers. This integration entails the assessment of disparities among the three environmental strategies (reactive, preventive, and proactive) in their utilisation of practices associated with green HRD. Furthermore, it involves the determination of horizontal consistency in HRD [26].

The integration of innovative HRM strategies in the transition to the CE has been fuelled by the emergence of new workforce development approaches [27,28,29]. In this sense, Tiwari and Mohammed [30] consider it essential to assess skill gaps and recommend individualised training in sustainability, ensuring that employees acquire green skills relevant to the performance of their duties.

Innovative SHRM strategies have been shown to include the continuous training of employees to develop green skills, the integration of gamification practices into environmental training, and the use of artificial intelligence to personalise sustainable learning plans [31,32,33,34]. These methods have been shown to increase employee engagement and motivation to adopt circular practices. In addition, the encouragement of sustainable careers through the provision of benefits and the alignment of internal policies with the SDGs has proven to be effective in the retention of talent committed to the CE [35,36]. These initiatives are pivotal for an effective transformation in organisational culture and ensuring the effective adoption of the CE in the long term.

Furthermore, adaptive learning models, which are based on real-time performance evaluation, are also increasingly being integrated into companies’ training programmes [37,38]. This enables continuous professional development and allows employees to keep up with regulatory changes related to the CE and the best practices being implemented [39]. As companies transition to CE-orientated business models, HRM strategies must evolve dynamically, promoting a resilient, skilled, and adaptable workforce for sustainable transformation [40,41,42,43,44].

2.2. Public Policies and Circular Economy

The recent literature highlights significant variations among countries in the implementation of the CE and the role of HRM in this process. The effective implementation of the CE is contingent on the existence of public policies and the provision of institutional support by governments [45]. Abu-Bakar et al. [46] posit that the existence of well-structured national policies can accelerate the adoption of the CE by promoting tax incentives for sustainable practices, environmental regulations, and education programmes with a view to sustainability. Sweden, for instance, has a consolidated history of pro-environmental policies that directly drive the private sector to adopt CE practices [47,48]. Conversely, in Portugal, the implementation of the CE, despite being encouraged by government policies resulting from the European framework, still faces challenges related to business adoption and professional training [49,50].

Research suggests that companies in countries with more robust environmental policies, such as Sweden, tend to have greater alignment between HRM practices and CE principles [51,52]. Conversely, countries undergoing a transition towards a circular model, such as Portugal, frequently encounter institutional and cultural impediments to the promotion of such an integration [53,54].

To accelerate the adoption of the CE, it is recommended that Portugal adopt specific HRM policies that encourage sustainability training for employees [55]. In addition, tax incentives could be introduced for companies that integrate sustainability KPIs into employee training and performance evaluation [56]. Furthermore, the expansion of partnerships between universities and companies to develop curricula in alignment with Circular Economy principles is recommended, ensuring that graduates possess industry-relevant sustainability skills [57].

It is evident that there are numerous successful HRM initiatives that are aligned with the CE and that provide valuable and essential information on which best practices should be implemented by companies in the future [58,59]. In Sweden, multinational companies such as IKEA and H&M have integrated CE principles into their HRM strategies [60,61]. This has been achieved by incorporating sustainability training into employee development programmes [62]. Bilderback [63] has noted that these initiatives include mandatory environmental training for all new hires, performance-based sustainability incentives, and collaborations with universities to develop CE-focused curricula. A critical success factor for Sweden is the comprehensive legislative support, which mandates sustainability reporting by companies and incentivises the integration of the CE [64,65].

In contrast, Portugal has made progress in CE-oriented HRM policies through initiatives such as green skills, from the European Climate Pact, which promotes professional training in sustainability in various sectors [66,67]. However, many Portuguese companies still struggle with fragmented sustainability training programmes and a lack of structured incentives for employees to develop CE-related skills [68,69]. Portugal needs a more structured framework that aligns HRM policies with CE objectives, facilitating the widespread adoption of sustainable working practices [68,70].

In this context, an analysis of the relationship between public policies and business practices can illuminate the factors that underpin the observed differences in progress between Portugal and Sweden. The article’s research question is derived from this analysis: To what extent do innovative HRM policies accelerate the transition to a CE?

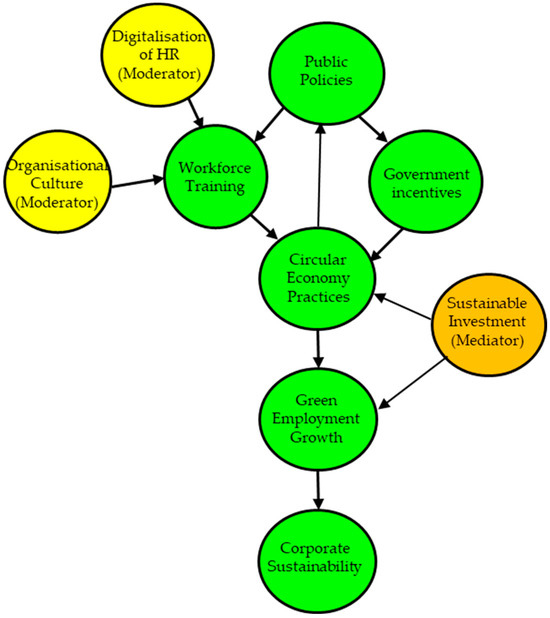

The conceptual model developed in this study posits that the adoption of the CE is driven by a set of interrelated factors, including public policies, government incentives and SHRM practices (Figure 1). The transition to the CE necessitates the implementation of strategies that promote continuous employee training, encourage the establishment of a sustainable organisational culture, and integrate digitalisation technologies into HR to optimise professional training and talent retention. The model incorporates mediating and moderating variables, including organisational culture and digitalisation in HR, which can influence the adoption of sustainable practices within companies. Furthermore, it establishes a dynamic relationship between the adoption of circular practices and the growth of green jobs, creating a feedback effect in which the advancement of the CE encourages new public policies and future investments. The model’s ability to elucidate these relationships facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the integration of SHRM and the CE, thereby providing a foundation for future research that is both quantitative and qualitative in nature. This research will examine the impact of organisational and government policies on the transition to the Circular Economy.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of HRM’s influence on Circular Economy transition. Source: author’s own work. Note: Yellow—moderator variables; Orange—mediator variable; Green—central and resulting variables.

2.3. Connecting Human Resource Management and the Circular Economy

The transition to a CE necessitates substantial structural modifications to business practices, with HRM assuming a pivotal role in this process by empowering, engaging, and aligning employees with society’s emerging sustainability imperatives [71]. The recent literature underscores that the CE’s implementation cannot be solely attributed to technological advancements and industrial innovation but is also contingent on cultural and organisational transformations facilitated by strategic HRM policies [72].

Talent management in a CE context involves several dimensions, including retraining, retaining green skills, and promoting a sustainable organisational culture [73]. Wodnicka [74] points to the need for reskilling and the development of green skills due to the CE’s demand for new knowledge and capabilities, making it essential to continually invest in training the workforce for circular processes.

The adoption of HRM practices by companies has been demonstrated to promote the alignment of organisational values with circular principles, thereby encouraging the active participation of employees in reducing waste and optimising resources. This, in turn, has been shown to develop involvement in the new circular organisational culture [75,76,77,78].

Finally, Atanasovska et al. [79] refer to the importance of flexible and innovative working models, with the CE stimulating and developing new working arrangements, such as remote working, the sharing economy, and inter-company collaborative practices to optimise human and physical resources.

However, despite the growing evidence of the importance of HRM in the CE, significant gaps still exist that hinder the effective implementation of this strategic alignment [24]. Research currently lacks standardised metrics to assess how HRM practices influence the adoption and success of the CE [80]. Many studies continue to rely on conventional sustainability metrics, neglecting to incorporate specific data on the impact of HRM on the transition to circularity [81].

As Grafström and Aasma [25] observe, traditional organisational culture, predicated on linear models of production and consumption, persists as a significant impediment. Employees and managers may exhibit reluctance in adopting circular practices due to a paucity of awareness, inadequate training, or the perception of substantial initial costs [82].

Despite the promotion of the Circular Economy by many governments through environmental policies, there remains a paucity of emphasis on the training of the workforce to deal with these changes [81]. Furthermore, human resource management strategies are rarely mentioned in government plans for the transition to a CE, creating a misalignment between regulation and business reality [83].

Most of the research in this field has been confined to individual case studies or literature reviews, with a paucity of empirical comparisons between different countries and industrial sectors. Comparative studies between nations with varying levels of development in the CE, such as Portugal and Sweden, could provide valuable insights for adapting good practices [84]. Based on the theoretical review, the following hypotheses are proposed for analysis:

Hypothesis 1:

Statistical evidence indicates that there is higher participation of workers in continuous training programmes for Circular Economy practices in Sweden than in Portugal.

Hypothesis 2:

The correlation between government investment in sustainable policies and the adoption of Circular Economy practices in Portugal and Sweden is statistically significant.

Hypothesis 3:

The adoption of sustainable human resource management practices has been demonstrated to be associated with a statistically significant increase in the growth of green employment in Portugal and Sweden.

3. Methodology

The present study adopts a quantitative approach, based on secondary data from Eurostat [85], analysing the period from 2014 to 2023. This interval was selected due to the availability of consolidated information on sustainable training and green employment, as well as covering the implementation of key European Union policies on the Circular Economy. To compare the adoption of circular practices between Portugal and Sweden, independent-sample t-tests were applied to assess whether there are statistically significant differences in participation in sustainable training and in the use of circular materials between the two countries. Furthermore, a linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the level of government investment in sustainability and growth in green employment.

This study’s dependent variables are the growth rate of green employment (measured by the evolution of the number of jobs in the environmental sector) and the rate of use of circular materials, and its independent variables are government investment in sustainable policies and participation in training and business education in favour of the Circular Economy.

The experimental tests were conducted using Excel software (Version 16.0) and validated by analysing the coefficients of determination (R2), significance values (p-value) and F-statistics. The employment of a significance level of p < 0.05 ensures that the findings are statistically robust. To ensure the reliability of the findings, the analyses were replicated and the outcomes were compared to each other, thus minimising the potential for sampling bias.

4. Results

The present study is chiefly reliant upon quantitative data from Eurostat, which supplies valuable information at a macro level, but does not capture HRM strategies at the company level or employees’ perceptions of transitions to a CE. In analysing Hypothesis 1, the objective is to ascertain whether there is a statistically significant discrepancy between Portugal and Sweden with regard to participation in continuing education and training between 2014 and 2023 among individuals aged between 25 and 64. To this end, the t-test for independent samples (two-sample t-test) was employed to examine the existence of any substantial disparities in the means of the two countries (Portugal vs. Sweden). The statistical results obtained are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participation rate in education and training (2014–2023).

The analysis demonstrates a discrepancy between the country averages, with Sweden at 32.26% and Portugal at 10.87%. T-statistics (17.6285) with a p-value of 8.4089 × 10−13 (significantly lower than 0.05) indicates a statistically significant difference between the two countries. This outcome thus provides robust confirmation of Hypothesis 1, demonstrating that Sweden exhibits a significantly higher level of engagement in continuing training programmes in comparison to Portugal. This finding serves to reinforce the theoretical argument that countries which invest more heavily in professional training (such as Sweden) are better able to align their workforce skills with the principles of the Circular Economy [23,77].

Sweden’s success in workforce training can be attributed not only to government policies, but also to the incorporation of sustainability competencies into employee development programmes by corporations. For instance, companies such as IKEA have integrated sustainability KPIs into employee performance appraisals, aligning HRM with CE principles [86]. Vocational training initiatives in Sweden are often co-funded by the government and the private sector, ensuring that CE-related competences remain aligned with industry needs [47]. In contrast, training in Portugal, although there is an effort to improve, still faces fragmentation and a lack of integration with corporate sustainability strategies [87]. This disparity underscores the necessity for Portugal to fortify public–private collaborations in the domain of vocational education, thereby paving the way for the integration of the CE.

Hypothesis 2 seeks to ascertain whether Portugal and Sweden show significant differences in the adoption of the Circular Economy over the years. Once again, the t-test for independent samples (two-sample t-test) was applied to data on the reuse of materials in the CE of the two countries. Table 2 shows the results obtained from the statistical analysis.

Table 2.

Circular Material Use Rate (2010–2023).

The findings of the study substantiate the statistically significant discrepancy in the circular material use rate between the two nations. The mean values demonstrate a clear divergence, with Sweden registering 7.73% and Portugal a mere 2.31%. The statistical test, known as the t-test, yielded a value of 11.7983, which, once again, indicates a statistically significant difference between the two countries. This is further corroborated by the p-value, which, at 6.1 × 10−12, is significantly lower than the 0.05 threshold, typically considered statistically significant. Consequently, it can be concluded that Sweden has a significantly higher rate of material reuse when compared with Portugal, suggesting a higher level of implementation of the Circular Economy. This outcome corroborates Hypothesis 2 and aligns with studies demonstrating that structured government policies directly influence the adoption of the CE [46,47].

The high use of circular materials in Sweden is driven by a combination of government policies and a business culture that prioritises sustainability [47]. The presence of eco-design regulations and product lifecycle management policies has encouraged companies to invest in circular production models [64]. For instance, the construction sector in Sweden has incorporated HRM-oriented sustainability training to ensure that employees adopt circular construction techniques [48]. In contrast, Portugal’s industrial sectors continue to rely heavily on linear production models, with limited incentives for companies to invest in sustainability training [88]. This absence of a cohesive strategy integrating HRM policies and sustainability-oriented business practices constitutes a significant impediment to the adoption of the CE in Portugal [89,90].

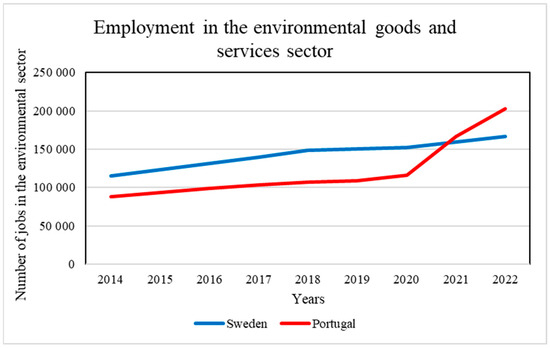

To test Hypothesis 3, which focuses on the increase in the number of environmental jobs in the countries between 2014 and 2022, linear regressions were carried out. The statistical outcomes of the regression are presented in Table 3, while the ANOVA test values are documented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Employment in the environmental goods and services sectors (2014–2022).

Table 4.

ANOVA Statistics.

Table 3 demonstrates a significant increase in the number of environmental jobs in Portugal and Sweden, respectively. Concerning the results of the regression test for Sweden, the R2 = 0.96 (demonstrating a very strong correlation) and the F-value = 1.15 × 10−5 (<0.05, therefore statistically significant). For Portugal, the R2 value is 0.73, indicating a strong correlation, though it is lower than that observed in Sweden. The significance value of the regression test is F = 0.006, and this is less than 0.05, thus indicating statistical significance. The differences between the two sets of data are clear in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Employment in the environmental goods and services sector. Source: author’s own work.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that both countries demonstrate statistically significant growth in sustainable employment, thereby validating Hypothesis 3. However, a closer examination reveals that Sweden exhibits more consistent and predictable growth (higher R2), while Portugal displays a more variable trend. This observation suggests that Swedish CE policies are characterised by enhanced structure and stability over time [49,50].

A comparison between the CE phase in Sweden and Portugal reveals notable disparities in adoption rates by companies, investments in labour retraining, and the effectiveness of regulatory incentives [88]. The Swedish CE model is characterised by comprehensive government policies (e.g., high taxation on waste production), extensive producer responsibility programmes, and strong financial incentives for circular business innovations [64,91]. This context leads Swedish companies to be proactive in integrating sustainability into HRM strategies, which leads to greater employee involvement in CE-orientated functions [92,93].

Portugal’s approach to the CE is still in a development stage, with policies that, although aligned with EU directives, do not have the same level of applicability and incentives as those in Sweden [94]. One of the main challenges in Portugal is the limited adoption of sustainability-oriented HRM practices in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which often lack the resources to implement large-scale workforce training programmes [88,95,96]. To enhance the transition to the CE, Portugal could consider implementing a fiscal policy that offers incentives to companies for investing in HRM training and establishing national benchmarks for sustainability-oriented education.

Despite an increase in green employment in both countries, Sweden’s more structured CE policies have been shown to contribute to a more stable and predictable growth trend [89]. This is evidenced by the higher R2 value in Sweden’s regression analysis, indicating consistent long-term investment in sustainability-related job creation. In contrast, Portugal’s green job growth exhibits greater variability, suggesting a reactive approach to sustainability initiatives and a less integrated role within long-term HRM strategies [88]. This finding lends further support to the notion that the sustained growth in the CE necessitates proactive alignment of HRM policies with national sustainability goals [97].

These findings corroborate the conclusions of previous studies that indicate a strong relationship between government policies and the adoption of circular practices [46]. However, this study goes further by demonstrating that, in addition to the presence of policies, the structuring of sustainable business training is a determining factor in the success of the transition to the CE. In countries such as Sweden, where the participation of workers in environmental training is high (32.26%), there is an ecosystem of innovation in sustainability. In contrast, Portugal still faces structural challenges in integrating these practices. These findings are consistent with those of Grafström and Aasma [25], who argue that organisational culture and market maturity are key determinants of EC adoption.

From an organisational perspective, this study underscores the significance of human resource practices aimed at sustainable talent retention, a component already embedded in leading Swedish companies such as IKEA and H&M [63].

In comparison, Portugal presents a challenging scenario, like that observed in other southern European countries [50]. Bilderback [63] emphasises that the lack of alignment between HR policies and sustainability goals results in a low adoption of the CE. The primary recommendation for Portugal is the establishment of national qualification programmes for green jobs, aligned with market demands, as well as the adoption of international benchmarks to measure progress in the transition to the CE. It is evident from case studies in Sweden that companies that implement continuous education and training, whilst integrating sustainability into their HR models, demonstrate greater resilience and innovation. The findings of this study are significant in the broader context of CE research, as they underscore the pivotal role of both government regulations and internal company practices in shaping the adoption of sustainability measures.

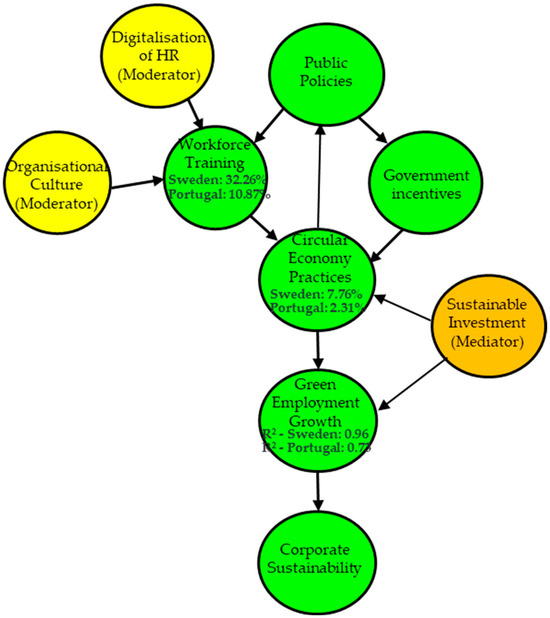

Following the quantitative analysis, the empirical results validate the conceptual model previously derived from the extant literature (Figure 3). The first conclusion to be drawn is that Sweden has a significantly higher participation in workforce training (32.26%) compared to Portugal (10.87%). The utilisation rate of circular materials in Sweden (7.73%) exceeds that of Portugal (2.31%), thereby confirming the impact of structured public/governmental policies. Conversely, the regression analysis confirms the growth of green employment in both countries; however, Sweden’s higher R2 (0.96) compared to Portugal’s (0.73) suggests a greater integration of GRHS into CE policies. This study thus lends support to the hypothesis that proactive HRM strategies, when combined with structured public policies, can enhance the implementation of the CE. However, it is recommended that Portugal consider ways to integrate workforce training more comprehensively to achieve a level of success comparable to that of Sweden.

Figure 3.

Conceptual model: tested impact of HRM on Circular Economy adoption. Source: author’s own work. Note: Yellow—moderator variables; Orange—mediator variable; Green—central and resulting variables.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

The statistical results offer validation for the three hypotheses that were put forward. Firstly, it is evident that Sweden allocates a greater proportion of its budget to continuous training, a strategy that is conducive to its transition to the CE (Hypothesis 1). Secondly, the adoption of the CE is notably higher in Sweden, a phenomenon that can be attributed to the influence of public policies (Hypothesis 2). Thirdly, the hypothesis concerning the growth of sustainable employment in both countries is substantiated, albeit to a greater extent in Sweden, reflecting its more robust environmental policies.

These results align with studies demonstrating that well-structured public policies foster the CE [45,46], with professional training being crucial to align the workforce with the CE, thereby reinforcing the conclusions of Shah et al. [77]. Finally, the growth of green jobs in Sweden corroborates the relationship between state investment and economic impact, as indicated by Henriques et al. [50].

This study contributes to the existing literature on human resource management and sustainability by providing empirical evidence on the role of employee training and political structures in the adoption of the CE. In contrast to previous studies that have primarily focused on the technological or economic drivers of the CE, this research highlights the central role of HRM in facilitating the transition to sustainability-oriented business models. By demonstrating the impact of workforce policies on CE practices, this study contributes to the discourse on sustainable employee management and offers a framework for integrating HRM into national sustainability strategies.

In conclusion, the present article makes a significant contribution to the extant literature on the subject by demonstrating the direct influence of workforce training and government policies on the adoption and implementation of the CE. It provides actionable insights for HRM professionals seeking to integrate talent management strategies that are oriented towards sustainability, and it offers recommendations for governments seeking to maintain ongoing policies to improve the alignment of their workforces with CE objectives.

Despite this study’s provision of substantial empirical evidence on the relationship between SHRM and the CE, it is imperative to acknowledge certain limitations. Firstly, the analysis is based on secondary data from Eurostat, which limits the understanding of the specific practices adopted by companies. Furthermore, this study’s exclusive focus on Portugal and Sweden may restrict the generalisability of the findings to other cultural and economic contexts. Future research could incorporate qualitative methodologies, such as interviews with HR managers, to further analyse the impact of internal HRM policies on the adoption of the CE.

It is recommended that future research endeavours concentrate on conducting qualitative assessments of CE-oriented HRM practices within companies. The research should incorporate qualitative methods, such as interviews with HR managers and employees, to understand the organisational challenges in adopting CE-oriented HRM policies. In addition, case studies of Swedish and Portuguese companies could help illustrate how different HRM strategies translate into effective workforce behaviour and sustainability performance. A comprehensive understanding of these perspectives would assist in addressing the discrepancy between national policies and the implementation of CE-aligned HRM in the workplace.

Conversely, future research endeavours should prioritise longitudinal studies of the workforce to assess the impact of HRM policies on CE adoption. Such studies could entail tracking employee engagement levels with CE training over time, the assessment of organisational changes in sustainability practices, and the measurement of how employee training influences long-term CE success.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilised in the study are publicly available and freely accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CE | Circular Economy |

| SHRM | Sustainable Human Resource Management |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| HRD | Human Resource Development |

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.K.A.; Ali, Z.; Rais, K. Green HRM for enhanced environmental performance: A circular economy perspective aligned with SDGs. Asian Bull. Green Manag. Circ. Econ. 2024, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthin, A.; Traverso, M.; Crawford, R.H. Circular life cycle sustainability assessment: An integrated framework. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongardt, A.; Torres, F. The European green deal: More than an exit strategy to the pandemic crisis, a building block of a sustainable European economic model. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2022, 60, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfsema, M.; van Soest, H.L.; Harmsen, M.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Bertram, C.; den Elzen, M.; Hohne, N.; Iacobuta, G.; Krey, V.; Vishwanathan, S.S.; et al. Taking stock of national climate policies to evaluate implementation of the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Anton, J.M.; Rubio-Andrada, L.; Celemín-Pedroche, M.S.; Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M. Analysis of the relations between circular economy and sustainable development goals. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavič, P. Evolution and current challenges of sustainable consumption and production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioatto, E.; Sospiro, P. Transition from waste management to circular economy: The European Union roadmap. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.R.; Varshney, D. Consumer protection frameworks by enhancing market fairness, accountability and transparency (FAT) for ethical consumer decision-making: Integrating circular economy principles and digital transformation in global consumer markets. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2024, 50, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.H.; Böhm, S.; Monciardini, D. The collaborative and contested interplay between business and civil society in circular economy transitions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2714–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Nguyen, N.P. Collaborative entrepreneurship and social innovation performance: Effects of institutional support and social legitimacy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5881–5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L.; Abbasi, K.R.; Hussain, K.; Alvarado, R.; Ramzan, M. Analyzing the role of green innovation and public-private partnerships in achieving sustainable development goals: A novel policy framework. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, H.; Wu, G.; Yuan, J. Public–private partnerships: A collaborative framework for ensuring project sustainable operations. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ma, M. Public–private partnership as a tool for sustainable development—What literatures say? Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borms, L.; Van Opstal, W.; Brusselaers, J.; Van Passel, S. The working future: An analysis of skills needed by circular startups. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 409, 137261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M.; Vitti, M.; Facchini, F.; Sassanelli, C. Mapping the relations between the circular economy rebound effects dimensions: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, C.P.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; del Río, P. How does corporate environmental culture enable the eco-innovation transition of firms towards the circular economy? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5911–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, X.; Lyu, C. Circular design strategies and economic sustainability of construction projects in China: The mediating role of organizational culture. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareliussen, J.; Purwin, A. Climate policies and Sweden’s green industrial revolution. In OECD Economics Department Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Favari, D.; Gastaldi, M.; Kirchherr, J. Towards circular economy indicators: Evidence from the European Union. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 0734242X241237171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Tran, T.P.T.; Ha, H.M.; Bui, T.D.; Lim, M.K. Sustainable industrial and operation engineering trends and challenges Toward Industry 4.0: A data driven analysis. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2021, 8, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Santa-Maria, T.; Kirchherr, J.; Pelzeter, C. Drivers and barriers for circular business model innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3814–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, C.F.; Sena, V.; Kwong, C. Dynamic capabilities and institutional complexity: Exploring the impact of innovation and financial support policies on the circular economy. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2023, 71, 9966–9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.; Kooli, C.; Alqasa, K.M.; Afaneh, J.; Fathy, E.A.; Fouad, A.M.; Fayyad, S. Resilience for sustainability: The synergistic role of green human resources management, circular economy, and green organizational culture in the hotel industry. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafström, J.; Aasma, S. Breaking circular economy barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Environmental strategies and human resource development consistency: Research in the manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, T.; Verma, P.; Gangaraju, P.K.; Nibhanupudi Siva Bhaskar, A.; Mahlawat, S.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S. Exploring the synergistic effects of circular economy, Industry 4.0 technology, and green human resource management practices on sustainable performance: Empirical evidence from Indian companies. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Appolloni, A.; Liu, J. Linking Top Management Commitment and Circular Practice Through Human Resource Perspective: Do Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Make a Difference in Sustainability? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 2746–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xi, M.; Wales, W.J. CEO entrepreneurial orientation, human resource management systems, and employee innovative behavior: An attention-based view. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2024, 18, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Mohammed, K.S. Unraveling the impacts of linear economy, circular economy, green energy and green patents on environmental sustainability: Empirical evidence from OECD countries. Gondwana Res. 2024, 135, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M. Green skills for sustainability transitions. Geogr. Compass 2024, 18, e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žiljak, T.; Pavicic, J.; Alfirevic, N. Mainstreaming Green Skills in EU Learning Policies. In Lifelong Learning for Green Skills and Sustainable Development: Southern European Perspectives; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimita, W.; Monoarfa, T.A.; Rahmi, R.; Wibowo, S.F.; Musyaffi, A.M. Enhancing Green Economic Circular Ecosystem Growth through AI-Based Waste Management Gamification. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2025, 15, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbi, N.M.; Sibaya, D.; Chibisa, A. Exploring pre-service teachers’ perspectives on the integration of digital game-based learning for sustainable STEM education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kücükgül, E.; Cerin, P.; Liu, Y. Enhancing the value of corporate sustainability: An approach for aligning multiple SDGs guides on reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C.G.; Bromaghim, E.; Kapuscinski, A.R. Sustainability careers. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 48, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, N.S.; Renumol, V.G. An improved adaptive learning path recommendation model driven by real-time learning analytics. J. Comput. Educ. 2024, 11, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunagalingam, A.; Addanki, S.; Vemula, V.R.; Selvakumar, P. AI in Performance Management: Data-Driven Approaches. In Navigating Organizational Behavior in the Digital Age with AI; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Ou, J.; Jia, F.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y. Circular economy practices and corporate social responsibility performance: The role of sense-giving. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 2208–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioatto, E.; Zecca, E.; D’Amato, A. Which innovations for Circular Business Models? A product life-cycle categorisation. Ind. Innov. 2024, 31, 809–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Ntsondé, J.; Beulque, R.; Micheaux, H. Business Models for Strong Circularity—The Role of Informative Policy Instruments Promoting Repair. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 2273–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, I.R.; Rosati, F.; Morioka, S.N. Determinants of circular business model adoption—A systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 6008–6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Hu, D.; Lou, X. The Impact of Digital Transformation on the Sustainable Growth of Specialized, Refined, Differentiated, and Innovative Enterprises: Based on the Perspective of Dynamic Capability Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ren, S.; Tang, G. In the era of responsible artificial intelligence and digitalization: Business group digitalization, operations and subsidiary performance. Ann. Oper. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Junjan, V.; Yazan, D.M.; Iacob, M.E. A systematic literature review on Circular Economy implementation in the construction industry: A policy-making perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 183, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Bakar, H.; Charnley, F.; Hopkinson, P.; Morasae, E.K. Towards a typological framework for circular economy roadmaps: A comprehensive analysis of global adoption strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, J.; McLaren, D. The political economy of circular economies: Lessons from future repair scenario deliberations in Sweden. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 1677–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, A.; Rashidghalam, M. Assessment of the urban circular economy in Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.N.; Seixas, C.; Castro, A.; Leitão, A. Promoting the transition to a circular economy: A study about behaviour, attitudes, and knowledge by university students in Portugal. Sustainability 2023, 16, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.; Ferrão, P.; Iten, M. Policies and strategic incentives for circular economy and industrial symbiosis in Portugal: A future perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, R.A.; Filho, M.G.; Ganga, G.M.D. Synergizing lean management and circular economy: Pathways to sustainable manufacturing. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Espíndola, O.; Cuevas-Romo, A.; Chowdhury, S.; Díaz-Acevedo, N.; Albores, P.; Despoudi, S.; Malesios, C.; Dey, P. The role of circular economy principles and sustainable-oriented innovation to enhance social, economic and environmental performance: Evidence from Mexican SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Torres-Guevara, L.E.; García-Díaz, C. Green marketing innovation: Opportunities from an environmental education analysis in young consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tan, F.J.; Ramakrishna, S. Transitioning to a circular economy: A systematic review of its drivers and barriers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matesanz, M.M.; da Silva Caeiro, S.S.F.; Bacelar Nicolau, P. Anticipating Future Needs in Key Competences for Sustainability in Two Distance Learning Universities of Spain and Portugal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Cordella, M.; Morone, P. Measuring investments progress in ecological transition: The Green Investment Financial Tool (GIFT) approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukiennik, M.; Zybała, K.; Fuksa, D.; Kęsek, M. The role of universities in sustainable development and circular economy strategies. Energies 2021, 14, 5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; Agarwala, T. Relationship of green human resource management with environmental performance: Mediating effect of green organizational culture. Benchmarking Int. J. 2023, 30, 2351–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihan, W.; Makhbul, Z.K.M.; Alam, S.S. Green human resource management in practice: Assessing the impact of readiness and corporate social responsibility on organizational change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, K.; Ratra, S. The Role of Circular Economy in Mitigating Climate Change: A Pathway to Reducing Global Carbon Footprint. In Innovating Sustainability Through Digital Circular Economy; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Acerbi, F.; Rosa, P.; Terzi, S. The role of digital technologies in the circular transition of the textile sector. J. Text. Inst. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M. Sustainable Outsourcing: Managing Global Responsibilities. In The Road to Outsourcing 4.0: Next-Generation Supply Chain; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilderback, S. Integrating training for organizational sustainability: The application of Sustainable Development Goals globally. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2024, 48, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekdahl, M.; Milios, L.; Dalhammar, C. Industrial policy for a circular industrial transition in Sweden: An exploratory analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 47, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl, K.; Dalhammar, C.; Brodén, E. Circular Economy Integration in Smart Grids: A Nexus for Sustainability. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 2119–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, G.; Ortega, E.; Semedo, A. Green HRM’s Effect on Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior and Green Performance: A Study in the Portuguese Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulovesi, K.; Oberthür, S.; van Asselt, H.; Savaresi, A. The European climate law: Strengthening EU procedural climate governance? J. Environ. Law 2024, 36, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, D.R.; Ortega, E.; Gomes, G.P.; Semedo, A.S. The impact of green HRM on employees’ eco-friendly behavior: The mediator role of organizational identification. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.; Simões, F.; Fernandes, B.; Fonseca, J. Designing vocational training policies in an outermost European region: Highlights from a participatory process. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 23, 524–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, C.; Varum, C.; Botelho, A. The role of public incentives in promoting innovation: An analysis of recurrently supported companies. Economies 2024, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Hoang, H.T.; Phan, Q.P.T. Green human resource management: A comprehensive review and future research agenda. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 845–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, A.; Singh, R.P.; Chauhan, N.S. Green Human Resource Management and Circular Economy. In Green Circular Economy: A New Paradigm for Sustainable Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.; Szabó-Szentgróti, G.; Walter, V. A systematic literature review on green human resource management (GHRM): An organizational sustainability perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2371983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodnicka, M. Skills Gap and New Technologies: Bibliometric Analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 3430–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graessler, S.; Guenter, H.; de Jong, S.B.; Henning, K. Organizational change towards the circular economy: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2024, 26, 556–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitha, K.; Kavitha, R. Exploring the Integration of Human Resource Management and Organizational Culture in Achieving Environmental Sustainability. In Intersecting Human Resource Management and Organizational Culture for Environmental Sustainability; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Singh Dubey, R.; Rai, S.; Renwick, D.W.; Misra, S. Green human resource management: A comprehensive investigation using bibliometric analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, E. Measurement and Assessment of Supply Chain Sustainability Performance. In Developing Dynamic and Sustainable Supply Chains to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Saha, K.; Budhwar, P.; De, D. Adoption of circular economy practices in small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from Europe. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasovska, I.; Choudhary, S.; Koh, L.; Ketikidis, P.H.; Solomon, A. Research gaps and future directions on social value stemming from circular economy practices in agri-food industrial parks: Insights from a systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 354, 131753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinante, C.; Sacco, P.; Orzes, G.; Borgianni, Y. Circular economy metrics: Literature review and company-level classification framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertassini, A.C.; Ometto, A.R.; Severengiz, S.; Gerolamo, M.C. Circular economy and sustainability: The role of organizational behaviour in the transition journey. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3160–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudusinghe, J.I.; Seuring, S. Supply chain collaboration and sustainability performance in circular economy: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 245, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, R.S.; de Vincenzi, T.B.; da Silva, A.L.F.; de Oliveira, M.C.C.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; Carvalho, M.M. How is the circular economy embracing social inclusion? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Brescia, V.; Esposito, P.; Amelio, S.; Biancone, P.P. Rethinking green investment and corporate sustainability: The south European countries experiences during the COVID-19 crisis. EuroMed J. Bus. 2023, 19, 1202–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M.; Silva, R.; Oliveira, C. Success factors of SMEs: Empirical study guided by dynamic capabilities and resources-based view. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J.P.; Couto, A.I.; Ferreira-Oliveira, A.T. Green Human Resource Management: Practices, Benefits, and Constraints—Evidence from the Portuguese Context. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, B.; Yau, N.; Hepburn, C. How stimulating is a green stimulus? The economic attributes of green fiscal spending. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 697–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smol, M. Inventory and comparison of performance indicators in circular economy roadmaps of the European countries. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 557–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrispim, M.C.; Mattsson, M.; Ulvenblad, P. Perception and awareness of circular economy within water-intensive and bio-based sectors: Understanding, benefits and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 464, 142725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droege, H.; Raggi, A.; Ramos, T.B. Co-development of a framework for circular economy assessment in organisations: Learnings from the public sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1715–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, M.F.; Tavares, V. Circular economy supporting policies and regulations: The Portuguese case. In Creating a Roadmap Towards Circularity in the Built Environment; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Galdeano-Gómez, E.; García-Fernández, R.M. Transition towards circular economy in EU countries: A composite indicator and drivers of circularity. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 6057–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo Melo, P.; Machado, C.F.; Brewster, C. Human resource management in small and medium-sized enterprises: A performance model definition. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 28, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Gomes, S.; Nogueira, E. Pathways to Circularity: Engagement Patterns of European SMEs in the Circular Economy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 3848–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyaningrum, R.P.; Muafi, M. Green Human Resources Management on Business Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Product Innovation and Environmental Commitment. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).