The Impact of Perceived Leadership Effectiveness and Emotional Intelligence on Employee Satisfaction in the Workplace

Abstract

1. Introduction

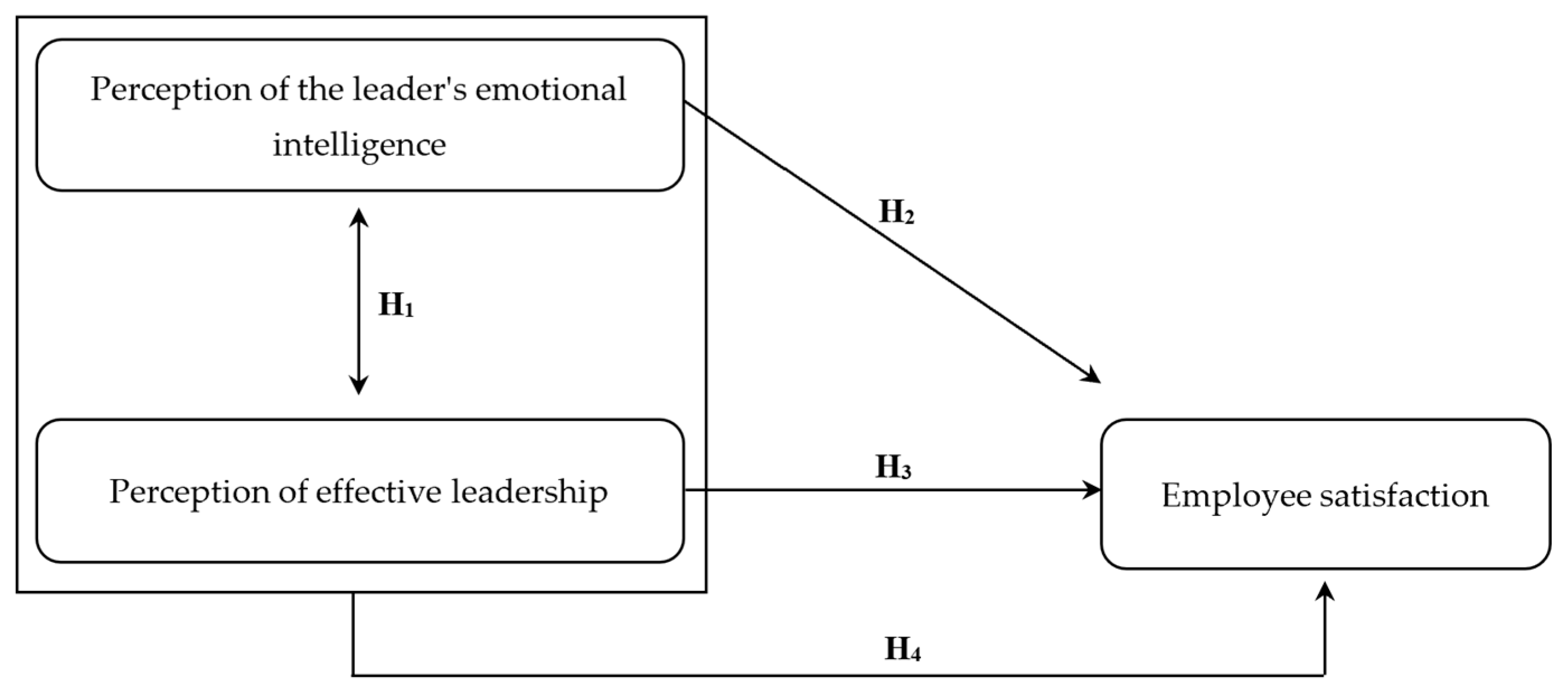

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Formulation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Procedure

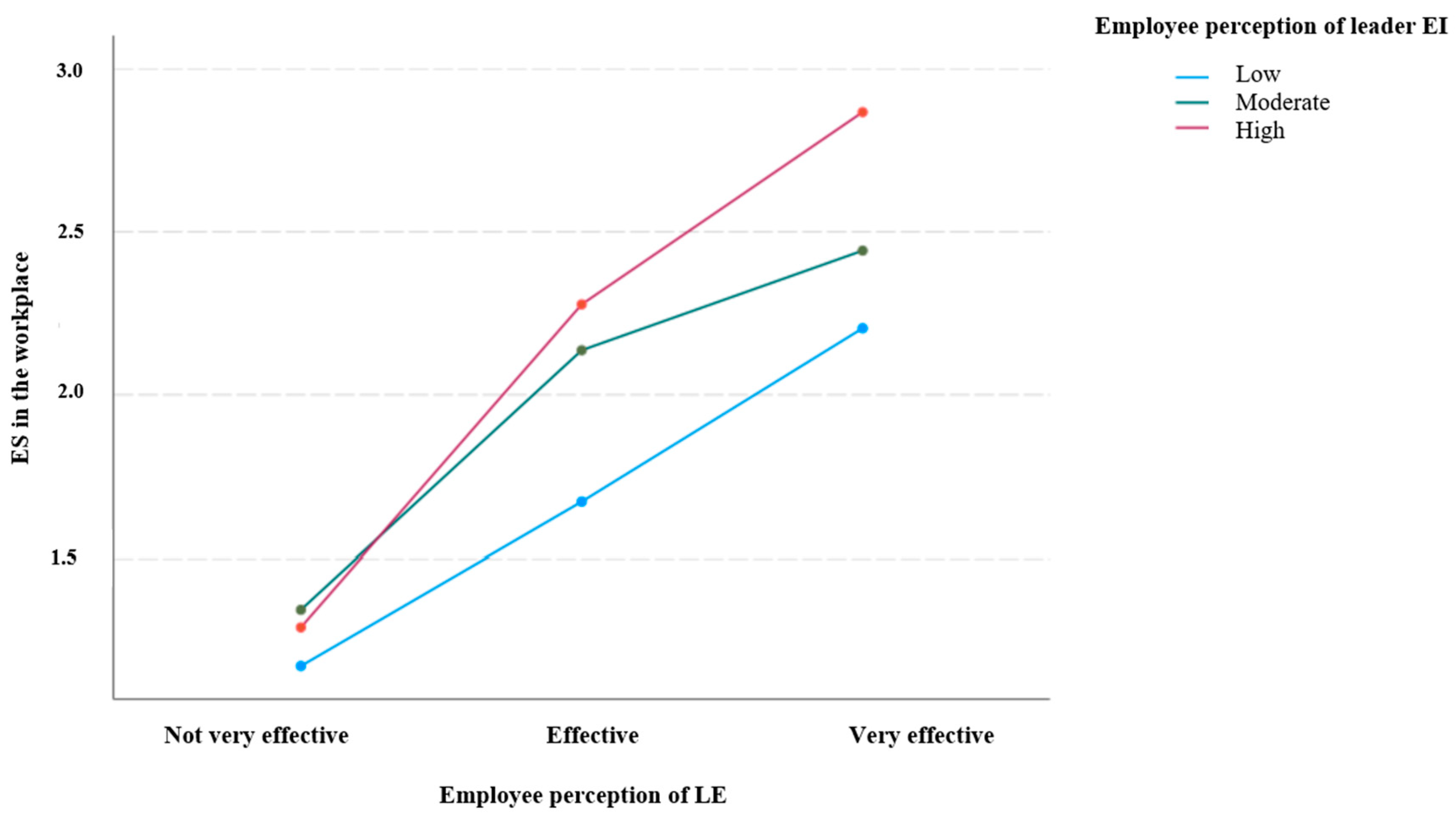

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

6.2. Study Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cameron, E.; Green, M. Making Sense of Change Management: A Complete Guide to the Models, Tools, and Techniques of Organizational Change; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Davidescu, A.; Apostu, S.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work Flexibility, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance among Romanian Employees: Implications for Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.; Gondim, S.; Magalhães, M. Relationship between emotional intelligence, congruence, and intrinsic job satisfaction. RAM Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2022, 23, eRAMG220152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.; Salovey, P. What Is Emotional Intelligence? Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ugoani, J. Salovey-Mayer emotional intelligence model for dealing with problems in procurement management. Am. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 6, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Coronado-Maldonado, I.; Benítez-Márquez, M. Emotional intelligence, leadership, and work teams: A hybrid literature review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, M.; Sutrisno, S.; Mahendika, D.; Suherlan, S.; Ausat, A. The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Effective Leadership: A Review of Contemporary Research. Al-Buhuts 2023, 19, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Das, R.; Lim, W.; Kumar, S.; Malik, A.; Chillakuri, B. Emotional intelligence and leadership: Insights for leading by feeling in the future of work. Int. J. Manpow. 2023, 44, 671–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Prabhakar, R.; Kiran, J. Emotional intelligence: A literature review of its Concept, models, and measures. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 2254–2275. [Google Scholar]

- Abelha, D.; Carneiro, P.; Cavazotte, F. Transformational Leadership and Job Satisfaction: Assessing the Influence of Organizational Contextual Factors and Individual Characteristics. Rev. Bras. Gestão Negócios 2018, 20, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orieno, O.; Udeh, C.; Oriekhoe, O.; Odonkor, B.; Ndubuisi, N. Innovative Management Strategies in Contemporary Organizations: A Review: Analyzing the Evolution and Impact of Modern Management Practices with an Emphasis on Leadership, Organizational Culture, and Change Management. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J.; Santos, M.; Rocha, R. Leadership Styles of Micro and Small Organizations in Maceió. RACE Rev. Adm. Cesmac 2020, 8, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.; Júnior, S.; Poli, B.; Oliveira-Silva, L. Analysis of Organizational Factors that Determine Turnover Intention. Trends Psychol. 2018, 26, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Paschoalotto, M.; Endo, G. The Organizational Leadership: A Brazilian Integrative Review. Rev. Pensamento Contemp. Adm. 2020, 14, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Udod, S.; Hammond-Collins, K.; Jenkins, M. Dynamics of Emotional Intelligence and Empowerment: The Perspectives of Middle Managers. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020919508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, C.; Engle, R.; Lang, G. The Unique and Common Effects of Emotional Intelligence Dimensions on Job Satisfaction and Facets of Job Performance: An Exploratory Study in Three Countries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 1562–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, R.; Chitra, A. Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction of Employees at Sago Companies in Salem District: Relationship Study. Adalya J. 2020, 9, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issah, M. Change Leadership: The Role of Emotional Intelligence. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018800910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, P. The Impact of Self-Awareness on Leadership Behavior. J. Appl. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanasy, N.; Daus, C. Emotional intelligence in the workplace. Wiley Encycl. Personal. Individ. Differ. Clin. Appl. Cross-Cult. Res. 2020, 4, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzlicht, M.; Werner, K.; Briskin, J.; Roberts, B. Integrating Models of Self-Regulation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H. The value of emotional intelligence: Self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, and empathy as key components. Tech. Educ. Humanit. 2024, 8, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, S.; Amin, M.; Winterton, J. Does Emotional Intelligence and Empowering Leadership Affect Psychological Empowerment and Work Engagement? Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 971–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberg, F. The Motivation to Work; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Peramatzis, G.; Galanakis, M. Herzberg’s motivation theory in workplace. Psychology 2022, 12, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D.; Seppala, E.; Zenger, J.; Folkman, J.; McKee, A.; Ruttan, R.; McDonnell, M.; Nordgren, L.; Solomon, L.; Kolko, J.; et al. Emotional Intelligence: Empathy; Harvard Business Review Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fianko, S.; Jnr, S.; Dzogbewu, T. Does the interpersonal dimension of Goleman’s emotional intelligence model predict effective leadership? Afr. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2020, 15, 221–245. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Krittayaruangroj, K.; Iamsawan, N. Sustainable Leadership Practices and Competencies of SMEs for Sustainability and Resilience: A Community-Based Social Enterprise Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbokwe, I.; Egboka, P.; Thompson, C.; Etele, A.; Anyanwu, A.; Okeke-James, N.; Uzoekwe, H. Emotional intelligence: Practices to manage and develop it. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2023, 1, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.; Şenyuva, E.; Bodur, G. The Relationship between Critical Thinking and Emotional Intelligence in Nursing Students: A Longitudinal Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štiglic, G.; Cilar, L.; Novak, Ž.; Vrbnjak, D.; Stenhouse, R.; Snowden, A.; Pajnkihar, M. Emotional Intelligence among Nursing Students: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 66, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwali, J.; Alwali, W. The relationship between emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and performance: A test of the mediating role of job satisfaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 43, 928–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Leadership: The Power of Emotional Intelligence; More Than Sound LLC: Northampton MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Krén, H.; Séllei, B. The role of emotional intelligence in organizational performance. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2021, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, T.; Tran, T. Job Satisfaction, Employee Loyalty, and Job Performance in the Hospitality Industry: A Moderated Model. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2020, 10, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakka, I.; Nokelainen, P.; Pylväs, L. Learning or Leaving? Individual and Environmental Factors Related to Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention. Vocat. Learn. 2021, 14, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.; Gaudet, M.; Vandenberghe, C. The Role of Group-Level Perceived Organizational Support and Collective Affective Commitment in the Relationship between Leaders’ Directive and Supportive Behaviors and Group-Level Helping Behaviors. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R.; Holzer, A.; Bradley, C.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Patti, J. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Leadership in School Leaders: A Systematic Review. Camb. J. Educ. 2022, 52, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Chelladurai, P. Emotional Intelligence, Emotional Labor, Coach Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention in Sport Leadership. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2018, 18, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Bustamante, J.; León-del-Barco, B.; Yuste-Tosina, R.; López-Ramos, V.M.; Mendo-Lázaro, S. Emotional Intelligence and Psychological Well-Being in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, C.; Afolabi, D. Leadership Style, Organizational Behaviour, and Employee Productivity: A Study of ECOWAS Commission, Abuja, Nigeria. Int. J. Dev. Manag. Rev. 2021, 16, 114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Benmira, S.; Agboola, M. Evolution of Leadership Theory. BMJ Lead. 2021, 5, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourani, R.; Litz, D.; Parkman, S. Linking Emotional Intelligence to Professional Leadership Performance Standards. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2023, 26, 1005–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, M.; Vijayakumar, M. Emotional Intelligence: A Review of Emotional Intelligence Effect on Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Job Stress. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. Dev. 2018, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpott, F.; Van Quaquebeke, N.; Schlamp, S.; Voelpel, S. An Identity Perspective on Ethical Leadership to Explain Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Interplay of Follower Moral Identity and Leader Group Prototypicality. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindeguia, R.; Aritzeta, A.; Garmendia, A.; Martinez-Moreno, E.; Elorza, U.; Soroa, G. Team Emotional Intelligence: Emotional Processes as a Link between Managers and Workers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, I.; Muniz, M. Emotional Intelligence, Intelligence, and Social Skills in Different Areas of Work and Leadership. Psico-USF 2022, 27, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mweshi, G.; Sakyi, K. Application of Sampling Methods for The Research Design. Arch. Bus. Rev. 2020, 8, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, F.; Lopes, C. A Inteligência Emocional Como Factor Determinante da Liderança. R-Lego 2019, 9, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schutte, N.; Malouff, J.; Hall, L.; Haggerty, D.; Cooper, J.; Golden, C.; Dornheim, L. Development and Validation of a Measure of Emotional Intelligence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1998, 25, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, L.; García-Cueto, E.; Muñiz, J. Effect of the Number of Response Categories on the Reliability and Validity of Rating Scales. Methodology 2008, 4, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; Podsakoff, N.; Williams, L.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, M. Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction: How Do They Work Together? In Proceedings of the 11th International Management Conference, Faculty of Management, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania, 2–4 November 2017; Volume 11, pp. 756–765. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/rom/mancon/v11y2017i1p756-765.html (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Tagoe, T.; Quarshie, E. The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in Accra. Nurs. Open 2017, 4, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Top, C.; Abdullah, B.; Faraj, A. Transformational Leadership Impact on Employees Performance. Eurasian J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.; Bryto, K. The Influence of Leadership on Organizational Productivity: Case Study at Solus Tecnologia. RAC Rev. Adm. Contab. 2019, 6, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, A.; Nozé, B.; Teixeira, C.; Calsani, J. The Importance of the Leader in Organizations. SITEFA Simpósio Tecnol. Fatec Sertãozinho 2020, 3, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussler, N.; Barth, E.; Binato, L. The Evolution of the Field of Organizational Behavior: A Bibliometric Analysis; XLIV Encontro da ANPAD; Universidade Federal de Goiás: Goiânia, Brazil, 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 366 | 70.7 |

| Female | 152 | 29.3 |

| Age group (M = 39.57; SD = 10.36) | ||

| 30 years old and below | 120 | 23.2 |

| Between 31 and 40 years old | 135 | 26.1 |

| Between 41 and 50 years old | 187 | 36.1 |

| 51 years old and over | 76 | 14.7 |

| Education Level | ||

| Less than bachelor’s degree | 154 | 29.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 206 | 39.8 |

| Higher than bachelor’s degree | 158 | 30.5 |

| Seniority (M = 11.61; SD = 8.12) | ||

| Less than or equal to 5 years | 147 | 28.4 |

| Between 6 and 10 years | 113 | 21.8 |

| Between 11 and 15 years | 116 | 22.4 |

| Greater than or equal to 16 years | 142 | 27.4 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee satisfaction in the workplace | 1.97 1 | 0.79 | (0.89) | ||

| Employee perception about LE | 2.02 1 | 0.83 | 0.815 ** | (0.97) | |

| Employee perception about EI | 2.05 1 | 0.83 | 0.369 ** | 0.196 ** | (0.86) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, R.; Teixeira, N.; Costa, B. The Impact of Perceived Leadership Effectiveness and Emotional Intelligence on Employee Satisfaction in the Workplace. Merits 2024, 4, 490-501. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040035

Rodrigues R, Teixeira N, Costa B. The Impact of Perceived Leadership Effectiveness and Emotional Intelligence on Employee Satisfaction in the Workplace. Merits. 2024; 4(4):490-501. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040035

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Rosa, Natália Teixeira, and Bernardo Costa. 2024. "The Impact of Perceived Leadership Effectiveness and Emotional Intelligence on Employee Satisfaction in the Workplace" Merits 4, no. 4: 490-501. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040035

APA StyleRodrigues, R., Teixeira, N., & Costa, B. (2024). The Impact of Perceived Leadership Effectiveness and Emotional Intelligence on Employee Satisfaction in the Workplace. Merits, 4(4), 490-501. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits4040035