Simple Summary

Childhood cancers differ fundamentally from adult cancers, not only in their genetic driver but also in the tumor microenvironment (TME)—the environment in which tumor cells grow. The TME consists of immune cells, supportive stromal cells, blood vessels, and the surrounding extracellular matrix. These interconnected elements collectively determine tumor development, metastatic potential, and response to therapeutic intervention. Compared to adult malignancies, pediatric tumors are characterized by reduced mutational burden, diminished T cell activation, and unique stromal cell interaction. These features account for the limited success of numerous immunotherapy approaches which are effective in adult populations. This comprehensive review examines the principal TME constituents in pediatric oncology and elucidates their roles in disease progression across multiple cancer types, including leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, various sarcomas, kidney tumors, and central nervous system malignancies. The analysis focuses on how various factors—including immune cell populations (such as T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and macrophages), inflammatory signaling molecules, tumor-associated fibroblasts, and oxygen-depleted conditions—drive cancer advancement and treatment resistance. The review also discusses innovative treatment approaches currently under investigation, including checkpoint blockade immunotherapy, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell and NK cell therapies. Gaining deeper insights into TME holds promise for designing more precise, individualized therapeutic interventions that can enhance survival and quality of life for pediatric cancer patients.

Abstract

The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays an important role in the development, progression, and treatment response of pediatric cancers, yet remains less elucidated compared to adult malignancies. Pediatric tumors are unique with a low mutational burden, an immature immune landscape, and unique stromal interactions. The resultant “cold” immune microenvironments limits the effectiveness of conventional immunotherapies. This review summarizes the key cellular and non-cellular components of the pediatric TME—including T cells, NK cells, tumor-associated macrophages, cancer-associated fibroblasts, extracellular matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, and hypoxia—and describes how these elements shape tumor behavior and therapy resistance. The role of TME in common pediatric cancers like leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, brain tumors, renal tumors, and sarcomas is discussed. Emerging therapeutic strategies targeting immune checkpoints, macrophage polarization, angiogenic pathways, and stromal barriers are discussed.

1. Introduction

The concept of the tumor microenvironment (TME) originates from Stephen Paget’s classical “seed and soil” hypothesis, which proposed that cancer growth and metastasis depend not only on malignant cells—the “seeds”—but also on the supportive surrounding tissue—the “soil”—that provides nutrients, oxygen, and molecular cues necessary for tumor evolution [1]. Today, the TME is understood as the dynamic network of immune infiltrates, stromal cells, vascular structures, and extracellular matrix (ECM) components that collectively shape tumor initiation, metastatic behavior, therapeutic resistance, and response to treatment [2]. In adult malignancies, the TME has gained substantial attention, particularly with the advent of immunotherapy, where “hot” tumors rich in T-cell infiltration demonstrate superior outcomes compared with immunologically “cold” tumors [3]. Although childhood cancers now achieve excellent survival owing to multimodal therapy, understanding of the TME in pediatric oncology is still emerging compared with adults, where its prognostic and therapeutic relevance is well established [4,5,6].

Pediatric tumors exhibit microenvironmental features that reflect their developmental biology. They generally harbor a lower mutational burden, possess well-defined genetic drivers, and arise within an immune system that is still maturing. These factors contribute to limited antigenicity, reduced T-cell priming, and distinct stromal and myeloid cell interactions compared with many adult tumors [7,8]. As a result, the biological behavior, metastatic patterns, and treatment responses of childhood cancers are deeply influenced by age-specific microenvironmental conditions. While the TME has been extensively characterized in adult malignancies, such depth of understanding is still lacking in pediatric cancers. Children’s tumors emerge in growing tissues, are frequently driven by fusion oncogenes, and demonstrate unique ECM dynamics and macrophage polarization patterns, emphasizing that the pediatric TME is a distinct biological entity rather than a simplified extension of adult models. Recent findings across leukemias, neuroblastoma, sarcomas, and pediatric brain tumors reinforce the need to study these microenvironmental processes to better understand treatment resistance and the variable performance of immunotherapies in children.

This review synthesizes the unique biological features of the pediatric TME, highlights key distinctions from adult tumors, and outlines emerging therapeutic implications and research priorities.

2. Key Components of TME

TME comprises both cellular and non-cellular elements that collectively regulate tumor growth, invasion, and therapeutic response.

2.1. Cellular Components

2.1.1. Immune Cells

Immune cells within the pediatric tumor microenvironment form a coordinated yet highly dysregulated network that shapes tumor control and immune escape. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes are central mediators of anti-tumor immunity, recognizing tumor antigens via TCR–MHC I interactions and inducing apoptosis through granzyme–perforin pathways or FASL–FAS signaling [9]. Their function is frequently compromised by PD-1/PD-L1 interactions that drive T-cell exhaustion, forming the basis for the use of checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 to restore cytotoxicity [10]. CD4+ helper T cells further modulate this landscape: Th1 cells enhance anti-tumor responses through IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion and by supporting CD8+ T-cell and B-cell activation, whereas Th2 cells release anti-inflammatory cytokines that can promote tumor progression [11,12]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) suppress effector T-cell activity through cytokine-mediated inhibition and metabolic disruption, maintaining immune balance but also contributing to tumor immune evasion, though their therapeutic targeting remains limited due to autoimmunity concerns [13,14]. B lymphocytes contribute dual roles by exerting anti-tumor functions such as antibody-dependent cytotoxicity and antigen presentation while also potentially promoting tumor growth through immunosuppressive cytokines and immune-complex formation [15].

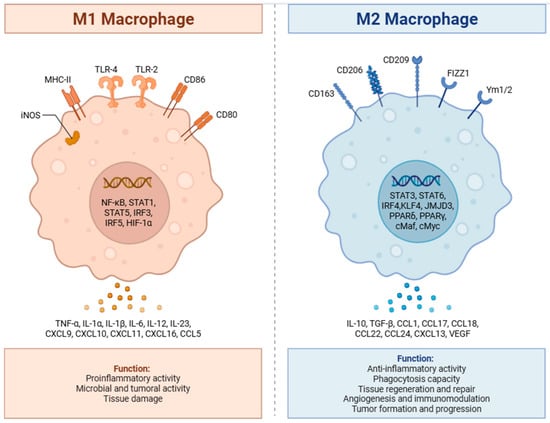

Among innate immune cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) constitute a major component—often 30–50% of immune infiltrates in pediatric solid tumors—and commonly display an M2-like, immunosuppressive phenotype expressing ARG1, CD206, and IL-10, correlating with poor outcomes such as in high-risk neuroblastoma [16,17,18]. Distinct TAM subsets with variable phagocytic and suppressive capacities have recently been described [19]. Natural killer (NK) cells show heterogeneous activity across pediatric tumors; in neuroblastoma, downregulation of activating receptors and heightened inhibitory signaling impair NK function, yet NK-based approaches (e.g., anti-GD2 therapy with cytokines) demonstrate therapeutic promise [20,21,22]. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) also accumulate in many pediatric cancers, mediating immunosuppression via arginine depletion, ROS generation, and Treg induction, and are typically associated with advanced disease and adverse outcomes [23,24]. Figure 1 illustrates role of macrophages in TME.

Figure 1.

Role of M1 and M2 macrophages in tumor progression. M1macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to their anti-tumor effect, while M2 macrophages have anti-inflammatory activity leading to tumor formation and progression. Created in BioRender. Batra, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ija1wc4 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

2.1.2. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs)

CAFs form a major stromal population in pediatric solid tumors and display marked functional and transcriptional heterogeneity. They comprise multiple subtypes—including myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs), inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), and antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs)—each with distinct spatial distribution and gene-expression signatures within the tumor landscape [11,25]. Their origins are equally diverse: depending on tumor context, CAFs may arise from resident fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells, stellate cells, or even adipocytes. Although several CAF subsets facilitate tumor progression, invasion, and immune evasion, others demonstrate tumor-restraining functions, underscoring their dual, context-dependent roles [26].

Beyond their stromal functions, CAFs actively shape tumor immunity. They secrete immunosuppressive cytokines and chemokines such as TGF-β and CXCL12, which recruit myeloid cells, enhance regulatory T-cell (Treg) accumulation, and suppress effector T-cell activity. Some CAF subsets also express MHC class II molecules but lack co-stimulatory signals, potentially driving antigen-specific T-cell dysfunction or anergy. Through these mechanisms, CAFs contribute to immune exclusion and limit the efficacy of immunotherapies. While targeted modulation of specific CAF subsets or their downstream pathways may enhance immune infiltration and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), indiscriminate CAF depletion can paradoxically worsen tumor behavior due to the presence of protective CAF phenotypes [27,28,29,30].

In pediatric solid tumors, the extracellular matrix (ECM) plays a critical structural and signaling role. Successful preclinical modeling of osteosarcoma and other sarcomas highlights the necessity of recapitulating ECM composition, because ECM influences tumor progression, metastasis, and drug response [31]. Growth factors and matricellular proteins such as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and TGF-β signaling are involved in stromal regulation of VEGF production and drug resistance in osteosarcoma. CAFs, along with tumor cells, secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) including MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-14, which remodel the ECM and release matrix-bound factors such as TGF-β and VEGF, increasing pro-tumorigenic signaling and angiogenesis [26].

Emerging evidence reveals complex interactions between stromal, immune, and vascular compartments in pediatric tumors. In osteosarcoma, denervation (interruption of sensory neural input) alters tumor-associated macrophage polarization and decreases vascularization, demonstrating that stromal inputs—including neural signals—shape immune phenotypes and angiogenesis. Additionally, VEGFR2 activity in tumor and stromal compartments is linked to PD-L2 expression, providing a mechanistic axis by which stromal/vascular signaling promotes immune suppression. These findings underscore the need for therapeutic strategies that address the integrated stromal-immune-vascular network rather than targeting single compartments in isolation [28,29].

2.1.3. Vasculature and Angiogenesis

Tumor angiogenesis is driven by hypoxia-induced release of VEGF, angiopoietins, and other cytokines, promoting rapid formation of abnormal, leaky vasculature. These immature blood vessels create impaired perfusion, acidosis, and high interstitial pressure, which support tumor growth while hampering immune cell infiltration and drug delivery. The VEGFA–VEGFR2 axis is the central pathway initiating neovascularization through endothelial proliferation and migration [31]. Without vascular support, many microscopic lesions remain dormant, as seen in autopsy studies of healthy individuals where subclinical tumors were found in organs like the breast and prostate. The angiogenic switch is a hallmark of tumor initiation, which involves coordinated signaling between cancer cells and the surrounding cells like, pericytes, endothelial cells, CAFs, and immune cells. This switch leads to transformation of a quiescent lesion into a vascularized, growing tumor [32]. Tumor-induced angiogenesis leads to the formation of tortuous and leaky vessels. These vessels appear disorganized with irregular endothelial lining and poor pericyte coverage. These abnormalities result in hypoxia, reduced immune cell penetration, and impaired drug delivery. Tumors may also use mechanisms like vessel co-option (using existing vasculature) or vascular mimicry (forming cancer cell-lined channels) to bypass traditional angiogenic pathways, leading to resistance against anti-angiogenic therapies [33,34].

Pediatric tumors exhibit distinct angiogenic features compared to adult malignancies. In sarcomas, a subpopulation of tumor cells co-expresses VEGF and VEGFR1, establishing autocrine VEGF/VEGFR1 signaling loops that promote constitutive receptor activation and support proliferation, survival, tumor growth, and osteolysis. This tumor-intrinsic angiogenic drive differs from the predominantly paracrine VEGF signaling observed in many adult carcinomas [31].

Beyond classical endothelial-driven angiogenesis, emerging evidence reveals that tumor-associated neural signals modulate VEGF signaling and vascularity in pediatric sarcomas. The TrkA/CGRP axis from sensory neurons influences vascular density, and neural inhibition reduces both vascularization and tumor progression in preclinical models. Importantly, some metastatic osteosarcoma models show upregulation of pro-angiogenic molecules without a clear in vivo angiogenic switch; in these contexts, elevated angiogenic signaling may support cell survival and metastatic colonization rather than robust neovascularization [35].

Multiple anti-angiogenic agents have been evaluated in pediatric solid tumors, with variable clinical outcomes. Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF-A, has shown preclinical efficacy in osteosarcoma by suppressing angiogenesis via modulation of extracellular-vesicle-transferred lncRNA/miRNA axes (MIAT/miR-613/GPR158), reducing both proliferation and angiogenesis in models. Multi-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) with anti-VEGFR activity—including pazopanib, sorafenib, regorafenib, anlotinib, lenvatinib, and cabozantinib—have demonstrated clinical responses in subsets of osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma patients, though responses are heterogeneous, resistance is common, and none have achieved regulatory approval for these indications [36].

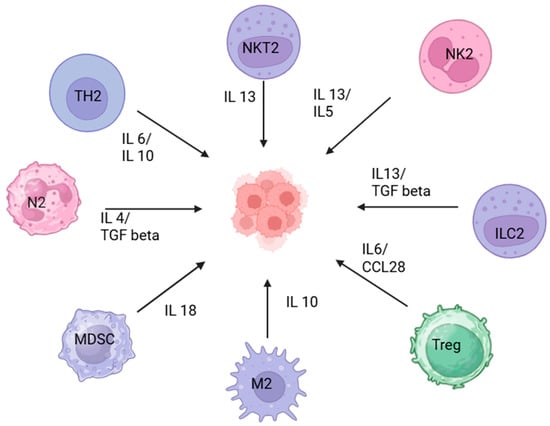

The tumor microenvironment plays a central role in promoting tumor immune escape and treatment resistance. Key cellular elements within the TME—such as cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and infiltrating immune cells—reshape local immunity by suppressing cytotoxic T-cell activity, altering antigen presentation, and facilitating immune checkpoint upregulation. These interactions collectively create a permissive niche that enables tumor progression despite host immune surveillance and therapeutic pressure [11,37,38]. Figure 2 illustrates the role of cytokines in the TME.

Figure 2.

Immunoregulatory landscape of the tumor microenvironment. The diagram illustrates various soluble factors and cytokines that affect the tumor microenvironment. Natural Killer T cells (NKT2), N2 neutrophils, M2 macrophages, Innate Lymphoid Cells type 2 (ILC2), and NK2 cells secrete IL-13, IL-4, IL-5, and TGF-β, promoting tumor-supportive inflammation and tissue remodeling. Th2 cells release IL-4 and IL-10, leading to anti-inflammatory signaling and suppression of cytotoxic responses. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) secrete IL-6 and CCL28, which inhibit effector T cell function and facilitate tumor immune escape. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) produce IL-18, further dampening anti-tumor immunity. Created in BioRender. Batra, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y52774v (accessed on 18 October 2025).

2.2. Extracellular Matrix (ECM) and ECM Remodeling

The ECM represents the principal non-cellular structural component of the TME and is composed largely of fibrous proteins such as collagen, laminin, fibronectin, and proteoglycans. CAFs, together with tumor-associated immune cells, continually remodel the ECM through proteolytic enzymes—most notably matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and lysyl oxidase (LOX). CAF-derived MMPs (including MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-14) degrade key ECM constituents and create permissive channels that facilitate tumor cell migration and metastasis. This remodeling also releases matrix-bound factors such as TGF-β and VEGF, intensifying pro-tumorigenic signaling and angiogenesis.

In parallel, LOX and LOX-like proteins catalyze cross-linking of collagen and elastin, increasing ECM stiffness. Such mechanical alterations activate integrin-dependent pathways—including FAK, Src, and YAP/TAZ—thereby promoting tumor proliferation, invasive behavior, and resistance to therapy. ECM composition and stiffness not only maintain the structural integrity of solid tumors but also preserve gradients of soluble mediators, contributing to a densely organized, immunosuppressive niche [39]. Moreover, excessive ECM deposition can physically exclude T cells from tumor nests and impede their activation. By sequestering cytokines and growth factors, the ECM also forms localized signaling hubs that further shape tumor–immune interactions [11].

3. Pediatric Versus Adult: Differences in TME

Adult cancers typically arise in tissues affected by chronic inflammation, environmental exposures, and age-related degeneration, leading to a high mutational burden and abundant neoantigens that shape a complex and immunologically active TME. This environment contains diverse immune infiltrates—including exhausted CD8+ T cells, Tregs, and MDSCs—and is further influenced by well-characterized stromal elements such as CAFs, which commonly secrete VEGF, CXCL12, and TGF-β to support tumor progression. The adult extracellular matrix (ECM) is often dense and fibrotic due to long-term collagen remodeling through enzymes like MMPs and LOX, and angiogenesis tends to be associated with immune-cell exclusion and treatment resistance. Consequently, adult tumors frequently show better responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors, with response rates of 20–40% or higher in many cancers [3,4,5,7,8].

In contrast, most pediatric tumors originate within developing tissues with minimal environmental exposure, resulting in a low mutational load, fewer neoantigens, and a relatively “cold” immune microenvironment with sparse immune-cell infiltration [3]. Although exceptions such as mismatch-repair-deficient glioblastoma or colorectal cancer can present hypermutated profiles resembling adult tumors [5,39], most pediatric tumors—including fusion-driven cancers—have distinct stromal and ECM characteristics shaped by developmental biology rather than accumulated damage [4,40,41,42]. Pediatric CAFs remain less understood, and ECM patterns in sarcomas and gliomas differ markedly from adults, influencing immune-cell movement and tumor expansion. Angiogenesis patterns also vary, as seen in neuroblastoma with high VEGF expression but weaker downstream immunosuppressive effects [3,43]. These unique features contribute to the limited efficacy of single-agent checkpoint blockade in children, where response rates commonly remain below 10–15%, in stark contrast to adult outcomes [44].

4. Role of TME in Various Pediatric Malignancies

The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a central role in shaping tumor biology, immune evasion, and treatment resistance across pediatric cancers. Although these malignancies differ in histology and molecular drivers, several recurring features—low mutational burden, predominance of M2-polarized macrophages, cytokine- and chemokine-driven stromal support, hypoxia-related signaling, and T-cell/NK-cell exhaustion—are consistently observed. To provide a unified framework before the disease-specific discussion, the key TME components, dominant cellular players, and major signaling pathways across pediatric tumors are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, which together highlight shared and divergent microenvironmental mechanisms relevant for therapeutic targeting.

Table 1.

Key TME concepts, molecules, and therapeutic targets in pediatric hematological malignancies.

Table 2.

Key TME concepts, molecules, and therapeutic targets in pediatric solid tumors.

4.1. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (All)

ALL is the most common childhood malignancy. B-ALL predominates in younger children, whereas adolescents more often present with T-ALL [45]. Survival in pediatric ALL has reached 80–85% with contemporary chemotherapy and can approach 90% with agents such as blinatumomab and CAR-T cell therapy [46]. Even in this highly curable disease, the bone marrow niche exemplifies core pediatric TME themes—stromal protection, immune dysfunction, and sanctuary-site biology.

4.1.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

Cytokine dysregulation is a hallmark of the leukemic niche. Increased IL-7, IL-8, and IL-15 support proliferation and survival through autocrine and paracrine signaling [47]. IL-7–JAK–STAT activation enhances leukemic fitness and contributes to treatment resistance [48,49]. Chemokine and adhesion axes such as CXCR4–CXCL12 enable blasts to anchor within protective stromal niches, activating downstream MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways and facilitating CNS and other sanctuary-site persistence [50]. NOTCH pathway activation—mutated in a substantial proportion of T-ALL—further integrates intrinsic oncogenic signaling with extrinsic microenvironmental cues [51,52,53].

Hypoxia and angiogenesis provide complementary survival advantages. HIF-1α stabilization under low oxygen tension promotes angiogenesis, metabolic adaptation, and maintenance of chemoresistant progenitors, while VEGF-driven angiogenesis correlates with increased marrow vascularity and vincristine resistance via VEGF–PI3K/AKT signaling [54]. Cell adhesion–mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR), mediated by VLA-4/VCAM-1 and cadherins, reinforces stromal protection and contributes to relapse, including in immunologically “cold” microenvironments typical of pediatric malignancies [55,56].

4.1.2. Potential Targets

Therapeutic efforts increasingly focus on disrupting microenvironmental support. Hypoxia-activated agents such as PR104 exploit low-oxygen niches to induce DNA crosslinking [57]. Inhibitors of HIF-1α and VEGF, including echinomycin, show preclinical activity by blocking hypoxia-driven resistance [58,59]. Proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, carfilzomib) exert dual pro-apoptotic and anti-angiogenic effects and may modulate NF-κB signaling and stromal interactions [60,61,62,63]. Strategies directed at CXCR4, PI3K/AKT, or NOTCH signaling aim to improve eradication of minimal residual disease and reduce CNS relapse by limiting leukemic retention in sanctuary sites. These approaches underscore how targeting the ALL microenvironment complements cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic strategies.

4.2. Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Acute myeloid leukemia is the second most common hematologic malignancy in children [46]. Chemotherapy remains the backbone of treatment, but hypomethylating agents, FLT3 and IDH inhibitors, BCL-2 blockade, and immunoconjugates increasingly shape modern AML management [64,65]. As in other pediatric cancers, stromal protection and immune suppression within the marrow niche critically influence persistence and relapse.

4.2.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

AML blasts depend on mesenchymal stem cells, T cells, cytokines, and soluble mediators to maintain a supportive bone marrow niche [66]. Immune evasion is central: upregulated PD-L1 on leukemic blasts inhibits PD-1–expressing cytotoxic T cells, particularly in relapsed/refractory disease [67,68]. Expansion of regulatory T cells suppresses effector proliferation and cytokine production, while dysregulated arginase and STAT3 signaling further promote T-cell exhaustion [69].

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) amplify immunosuppression via PGE2, IDO, and leukemia-derived exosomes [70]. AML also interferes with NK-cell immunity through downregulation and shedding of NKG2D ligands, weakening innate recognition [71]. Cytokines such as IL-2, IL-7, IL-10, and TGF-β shape both leukemic proliferation and Treg expansion, reinforcing a low-immunogenicity environment. Hypoxia-driven HIF-1α activity enhances angiogenesis and supports chemoresistant progenitors, mirroring hypoxia-related adaptations across pediatric cancers [66,70].

4.2.2. Potential Targets

Therapeutic strategies increasingly aim to reverse microenvironmental immunosuppression and reprogram the AML niche. PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA-4, and TIM-3 blockade—alone or in combination with hypomethylating agents—has shown immunologic reactivation and potential clinical benefit [72,73]. Novel immune constructs such as APVO436 and flotetuzumab are under evaluation in relapsed/refractory settings [74]. Antibody–drug conjugates targeting CD33 (GO), CD123, and CLL-1 improve outcomes in defined subsets with reduced off-target toxicity [75,76].

Cellular therapies (CAR-T and CAR-NK cells directed at CD123 or CD33) are being explored, though their success is moderated by cytokine toxicity and diminished NK-cell reserves in heavily pretreated children [77,78]. Cytokine-based strategies such as IL-15 super agonists (N-803) and IL-12/IL-18 stimulation aim to enhance NK and T-cell cytotoxicity [79]. Targeting suppressive mediators—IDO, TGF-β, PGE2—offers additional avenues to restore effector responses and dismantle Treg/MDSC-driven suppression [80,81]. Vaccine platforms (WT1 peptide and dendritic-cell vaccines) show early promise, particularly in minimal residual disease where a less burdened TME may be more amenable to immune activation [82].

4.3. B Cell Lymphomas

Pediatric aggressive mature B-cell lymphomas, predominantly Burkitt lymphoma (BL) and less commonly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), account for most non-Hodgkin lymphomas in children. Cure rates with multiagent chemotherapy exceed 90%, but relapsed or refractory disease remains challenging [83]. Compared with adults, these lymphomas illustrate a relatively more immunoreactive pediatric TME, with implications for immunotherapy.

4.3.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

In adult B-cell lymphomas, the TME is typically immunosuppressive, with M2-polarized macrophages, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), MDSCs, and dense fibrotic stroma that impair drug delivery and foster T-cell dysfunction [84,85]. Pediatric B-cell lymphomas generally show higher densities of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and NK cells, fewer MDSCs, and less stromal or CAF-driven ECM remodeling. This relatively “permissive” TME likely contributes to superior chemotherapy responsiveness and may offer a more favorable context for immunotherapies. While adult markers such as CD163+ TAMs and PD-L1+ cells predict poor outcomes, pediatric prognostic TME signatures are less well defined [86,87].

4.3.2. Potential Targets

Therapeutic exploration focuses on modulating macrophage and neutrophil biology, enhancing NK-cell cytotoxicity, and reversing T-cell exhaustion. TAM-directed approaches include CSF-1/CSF-1R blockade and CCR2 inhibition to prevent macrophage recruitment, while CD47–SIRPα inhibitors promote phagocytosis and demonstrate synergy with rituximab [88]. MicroRNAs such as miR-130 and miR-155 can repolarize TAMs toward an M1 phenotype, restoring pro-inflammatory antitumor activity [89]. Modulation of TAN biology through CXCR2, CXCR4, or TLR9 inhibition has shown potential in limiting TAN-mediated proliferation; in BL, the anti-SIRPα antibody KWAR23 enhances neutrophil-dependent phagocytosis [90].

Enhancing NK-cell activity through blockade of PD-1, KIRs, or NKG2A and cytokine stimulation with IL-2 or IL-15 can improve NK-cell persistence and cytotoxicity; lirilumab, an anti-KIR antibody, has shown synergy with rituximab [91]. HIF-2α inhibitors (e.g., MK-6482, PT2385), established in RCC, are emerging as potential tools for lymphoma TME modulation [92]. Checkpoint inhibition with PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 blockade, and next-generation bispecific agents such as YM101 (PD-L1/TGF-β), aim to convert “cold” TMEs into more inflamed, therapy-responsive states [93]. CAR-T, CAR-NK, and “armored” CAR platforms targeting CD19, CD22, and other antigens are being designed to resist TME-driven exhaustion and remodel the microenvironment [94].

4.4. Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma is among the most curable childhood cancers, with survival exceeding 90% in high-income settings [95]. Standard first-line regimens such as ABVD achieve excellent outcomes, yet a subset of patients has primary refractory disease or relapses [96]. HL is a prototypical example where a small malignant cell fraction is sustained by a dominant, immune-sculpted TME.

4.4.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

Classical HL (cHL) is characterized by a minority of malignant Reed–Sternberg (RS) cells embedded in a rich inflammatory TME dominated by CD4+ Th2 cells and Tregs, with relative depletion of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and Th1 subsets [97,98]. RS cells secrete chemokines such as TARC (CCL17), RANTES (CCL5), and MDC (CCL22), which preferentially recruit CD4+ cells and Tregs, reinforcing local immune escape [99]. Tumor-associated macrophages are predominantly M2-polarized and driven by IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 and MIF, promoting angiogenesis, ECM remodeling, and immune suppression. RS-derived IL-6 and IL-10 correlate with B symptoms, advanced disease, and inferior responses to therapy [100]. TARC also functions as a diagnostic and response biomarker, with serum levels reflecting tumor burden [101].

Epstein–Barr virus contributes substantially to HL pathogenesis in children and older adults and is detected in ~40% of pediatric cHL in developed regions. EBV+ RS cells exhibit type II latency, expressing LMP1, LMP2A, EBNA1, and EBERs. LMP1 mimics CD40 signaling and activates NF-κB, while LMP2A delivers BCR-like survival signals [102,103,104]. Exosome-mediated communication further shapes the TME; RS-derived exosomes enriched in CD30, cytokines, and miRNAs (e.g., miR-155, miR-21) promote fibroblast activation, cytokine release, and tumor progression [105,106].

Pediatric HL exhibits meaningful differences from adults. The microenvironment is generally less immunosuppressive, and markers such as CD68+ TAMs—strongly prognostic in adults—do not consistently correlate with outcomes in children. Conversely, higher CD163+ TAMs predict adverse outcomes in EBV-negative pediatric cHL, while EBV-negative disease may be more adverse in children than EBV-positive disease, in contrast to adults [97].

4.4.2. Potential Targets

Checkpoint blockade has transformed HL therapy. Anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) and CTLA-4 inhibitors (ipilimumab) have demonstrated efficacy in refractory disease and are being incorporated earlier into treatment algorithms [107,108,109,110,111]. Newer PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors such as atezolizumab and durvalumab are being evaluated primarily in adults, and additional checkpoints—LAG-3 (relatlimab), TIM-3 and others—are under early investigation as monotherapy or in combination with PD-1 blockade [112]. These agents directly address the immune-dominant nature of the HL TME and offer a paradigm for TME-directed therapy in pediatrics.

4.5. Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children and the most frequent primary intra-abdominal malignancy. Risk stratification incorporates clinical stage, histology, ploidy, and MYCN amplification, with high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-NB) still associated with ~50% survival despite intensive multimodal therapy [113,114]. HR-NB exemplifies a solid-tumor TME marked by immune exhaustion and myeloid suppression.

4.5.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

The neuroblastoma TME comprises diverse immune and stromal elements that vary with stage, MYCN status, and prior therapy. High-resolution techniques such as single-cell RNA sequencing have revealed prominent T-cell exhaustion, driven by PD-1, LAG-3 and other inhibitory receptors [115,116]. Tregs expressing CTLA-4 and TIGIT further suppress antitumor immunity. Increased infiltration of naïve B cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells correlates with improved survival, independent of MYCN amplification [117,118].

Myeloid components—including M2-polarized macrophages and TANs with PMN-MDSC–like functions—are enriched in aggressive disease and associate with poor prognosis and treatment resistance [119]. The stromal compartment, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), secretes immunosuppressive cytokines such as CXCL12, CSF-1, and CCL2. Distinct CAF subsets exert differential effects: CAF-S1 promotes immune suppression, whereas CAF-S4 supports invasion and metastasis [120,121]. Together, these elements create a TME with low neoantigen burden, immune exhaustion, and stromal-mediated therapeutic resistance, consistent with broader pediatric solid tumor patterns.

4.5.2. Potential Targets

Anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies remain central in HR-NB immunotherapy. Dinutuximab enhances ADCC, particularly when combined with IL-2 or GM-CSF and improves event-free and overall survival; Naxitamab is another anti-GD2 antibody in clinical use [122,123,124]. Checkpoint inhibitors, alone or in combination with anti-GD2 therapy or chemotherapy, aim to reverse T-cell exhaustion, with combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade showing additive efficacy in preclinical models [125,126].

Macrophage-directed therapies include magrolimab (anti-CD47), which promotes macrophage-mediated phagocytosis [127], and CSF1R or MCP-1 targeting to reduce M2 infiltration and augment chemotherapy responsiveness [128]. Anti-VEGF agents such as bevacizumab have been explored for angiogenesis inhibition [43]. Strategies targeting MSCs (e.g., IFN-γ–secreting MSCs, mobilizing agents such as plerixafor) and agents like fostamatinib, which reprogram M2 macrophages toward M1 and synergize with checkpoint inhibitors, are under investigation [116,129]. Early clinical studies of GD2-directed CAR-T cells have shown partial responses and disease stabilization, and next-generation constructs—including dual-target CARs (e.g., GD2 + B7-H3) and CAR-TIL hybrids—aim to improve specificity and persistence while limiting neurotoxicity [130,131].

4.6. Pediatric Brain Tumors

Pediatric brain tumors are now the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in children. Medulloblastoma (MBL), high-grade pediatric gliomas (pHGGs) and ependymomas are the most common malignant CNS tumors [132,133]. The CNS setting accentuates core pediatric TME themes—low neoantigen burden, immune exclusion, and limited effector T-cell infiltration—within an immune-privileged site.

4.6.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

Medulloblastoma comprises four molecular subgroups: WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4. SHH-MBLs show the highest immune infiltration, whereas Group 3 and Group 4 tumors demonstrate marked immune exclusion [134]. NK cells display downregulated NKG2D expression due to TGF-β–mediated suppression, including via microRNA-1245, resulting in NK-cell exhaustion [135,136]. CD8+ T-cell infiltration correlates with favorable outcomes. SHH tumors have the greatest PD-L1 expression, while MYC-amplified Group 3/4 tumors show lower PD-L1 but upregulate CD47, impairing dendritic-cell antigen presentation and T-cell priming [137,138,139]. TAMs, especially in SHH and Group 4 tumors, contribute to progression through IGF1- and ERBB4-driven pathways [140].

High-grade pediatric gliomas, including diffuse midline gliomas (DMGs), often harbor H3K27M mutations that disrupt epigenetic regulation and immune surveillance [141]. These tumors are characterized by minimal CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltration, low PD-L1 expression, and an immune-silent microenvironment. NK cells are present but functionally ineffective because of TGF-β signaling and LSD1-mediated suppression of ligands such as SLAMF7 and MICB. Unlike adult gliomas, TAMs in DMGs do not adopt a clear M1 or M2 phenotype, further limiting antitumor immunity [132]. An exception is hypermutated pHGGs with biallelic mismatch repair deficiency (bMMRD), which has high neoantigen load and better responses to checkpoint blockade [142,143].

4.6.2. Potential Targets

Checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and CTLA-4 have demonstrated activity in selected cases of DIPG and medulloblastoma, and newer agents continue to expand this landscape. TIM-3 blockade induces CD8+ activation and tumor regression in DIPG models, offering an avenue beyond PD-1/PD-L1 signaling [144,145]. CSF1R inhibitors (e.g., PLX5662) and galectin-3 inhibitors aim to reprogram TAMs toward an M1 phenotype to enhance immune activity [146,147]. BTK inhibition combined with IDO blockade (e.g., ibrutinib + indoximod) promotes differentiation of inflammatory dendritic cells and improves T-cell priming [148,149,150].

Oncolytic virotherapy (e.g., DNX-2401, reovirus) and peptide vaccines targeting CMV antigens, H3K27M mutations, or survivin (SurVaxM) have shown immune activation and early survival signals [151,152,153]. CAR-T cell therapies directed at GD2, B7-H3, HER2, and EGFR806 are under phase I testing for DIPG and MBL, with locoregional delivery (intratumoral, intraventricular, catheter-based CNS infusion) being explored to bypass the blood–brain barrier [154,155,156,157]. Focused ultrasound (FUS) and intracerebroventricular (ICV) delivery may further enhance drug and T-cell penetration in high-grade pediatric gliomas [158].

4.7. Wilms Tumor and Other Pediatric Renal Tumors

Wilms tumor (WT) is the most common primary renal malignancy in children. Less frequent pediatric renal cancers include malignant rhabdoid tumor of the kidney (MRTK), clear cell sarcoma of the kidney (CCSK), and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [159]. While outcomes for WT are generally excellent, anaplastic WT and aggressive non-Wilms tumors remain challenging and illustrate how renal TMEs combine innate immune skewing and stromal activation.

4.7.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

The TME in WT comprises immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive components, but the innate landscape is dominated by M2-polarized macrophages. Their density increases with tumor stage and correlates with unfavorable histology and inferior survival [160]. TAMs, together with COX-2, VEGF, IL-6/pSTAT3 and HIF-1α, contribute to tumor progression, angiogenesis, and a protumoral milieu [161,162]. PD-L1 expression is variable (14–35%), with higher levels observed in anaplastic and metastatic WT and associating with poorer outcomes [163].

MRTK, driven by loss of SMARCB1 or SMARCA4, shows high cytolytic immune activity despite a low mutational burden, with enrichment of CD68+ macrophages and CD8+ T cells and heterogeneous checkpoint expression [164,165]. CCSK, characterized by BCOR internal tandem duplications or YWHAE–NUTM2B/E fusions, shows a low Immunologic Constant of Rejection (ICR) score but Th1-skewed inflammatory signatures, though data remain limited because of rarity [166,167,168]. Overall, pediatric renal tumors share key pediatric-TME features: low neoantigen burden, M2 macrophage predominance, and stromal activation influencing therapeutic response.

4.7.2. Potential Targets

Checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 have shown limited but encouraging activity, reflecting variable PD-L1 expression in WT [169,170]. In MRTK, more consistent PD-1 expression has prompted ongoing trials of ICIs in this aggressive tumor [171,172]. B7-H3 (CD276) is overexpressed in WT and pediatric RCC and correlates with metastatic disease and poor prognosis [173]. Monoclonal antibodies such as MGA271 and B7-H3–directed CAR-T cell therapies are under active investigation [174,175].

COX-2, a key immunosuppressive enzyme implicated in TAM recruitment and angiogenesis, is expressed in WT and RCC. COX inhibitors such as celecoxib are being evaluated as adjuncts to disrupt this pro-tumoral axis [176,177]. Additional emerging strategies include macrophage-modulating agents, angiogenesis inhibitors, and multi-antigen immunotherapies, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Potential targets and the agents currently under trial for pediatric renal tumors.

4.8. Osteosarcoma

Role of tumor microenvironment: Osteosarcoma, the most common primary malignant bone tumor in children and adolescents, exemplifies the complexity of the pediatric tumor microenvironment. The osteosarcoma TME is characterized by a heterogeneous cellular milieu including malignant osteoblastic tumor cells, endothelial cells, immune infiltrates, and an ECM-rich stroma that collectively influence disease progression and therapeutic response. Subsets of osteosarcoma cells drive autocrine VEGF/VEGFR1 signaling and express transcriptional regulators (e.g., ID1) that increase VEGF-A production and microvessel density, implicating tumor-intrinsic control of angiogenesis. In some metastatic models, elevated angiogenic molecule expression is associated more with cell survival and metastatic fitness than with a full angiogenic phenotype, suggesting heterogeneity in angiogenic dependence across osteosarcoma clones. VEGFR2 activation promotes metastasis and upregulates PD-L2 through STAT3 and RhoA–ROCK–LIMK2 signaling, linking angiogenesis to immune evasion [187].

Stromal architecture: The dense ECM in osteosarcoma influences tumor progression, metastasis, and drug response. CTGF and TGF-β signaling modulate VEGF production by stromal elements and contribute to drug resistance phenotypes. Neural inputs from sensory neurons (TrkA/CGRP axis) modulate VEGF signaling and vascularity, and neural inhibition reduces vascular density and tumor progression [188].

Immune landscape: Osteosarcoma typically displays an immunosuppressive TME with M2-polarized macrophages and limited T-cell infiltration. VEGFR2-mediated PD-L2 expression supports immune escape mechanisms [189]. Interruption of sensory neural input alters macrophage polarization and reduces tumor growth and vascularity, demonstrating a noncanonical route by which the microenvironment enforces immunosuppression. High macrophage infiltration is linked to reduced survival in osteosarcoma, and TAMs promote immunosuppression and metastasis.

Potential Targets: Preclinical and translational data linking VEGFR signaling to immune checkpoints support rational combinations of anti-angiogenic RTK inhibitors with immune modulation. Multi-RTK inhibitors with VEGFR activity (pazopanib, sorafenib, regorafenib, anlotinib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib) have produced clinical responses in subsets of osteosarcoma patients, though responses vary and no agent has achieved definitive registration for this indication. Bevacizumab shows mechanism-level inhibition of osteosarcoma angiogenesis through modulation of extracellular vesicle miRNA/lncRNA axes in models [190].

4.9. Other Sarcomas

Sarcomas in pediatrics represent a heterogeneous group comprising mainly rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcoma (NRSTS), Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Nonmetastatic disease can be managed with multimodal therapy, whereas advanced metastatic disease continues to have poor outcomes [191]. Sarcomas highlight how myeloid-dominant, immunosuppressive TMEs can limit the success of otherwise intensive treatment.

4.9.1. Role of Tumor Microenvironment

Tumor-associated macrophages are the commonly found immune cells in pediatric sarcomas. TAMs promote tumor proliferation and metastasis, and their presence correlates with poor prognosis in several sarcoma subtypes [188]. They frequently express CD206 and CD163, indicative of M2 polarization, and secrete immunosuppressive cytokines that inhibit cytotoxic T-cell responses. Tumor cells exploit “don’t eat-me” signals such as CD47 to inhibit phagocytosis, while TAMs upregulate inhibitory ligands including PD-L1 and PD-L2 [192,193,194,195,196]. TAMs also promote angiogenesis via VEGF and chemokines such as CCL2 and CXCL8, and support metastasis by facilitating intravasation, migration, and establishment of pre-metastatic niches through CSF-1 and other pathways [197,198,199].

Ewing sarcoma typically displays an immunosuppressive TME with M2 macrophages as the predominant immune cell subset. The presence of M2 macrophages is linked to reduced survival in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Elevated CTLA-4 expression in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and expansion of CD14+ HLA-DR^lo/neg monocytes, are markers of systemic immunosuppression and advanced osteosarcoma [200,201]. Table 3 provides a summary of key TME concepts and targets in pediatric cancer.

4.9.2. Potential Targets

A major therapeutic approach is repolarization of TAMs from an M2 to an M1 phenotype. Liposomal muramyl tripeptide phosphatidylethanolamine (L-MTP-PE), a TLR4 agonist, enhances M1 polarization and has shown a survival benefit in osteosarcoma, although it is not FDA approved [202]. Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tested in both aerosolized and subcutaneous forms in RMS and Ewing sarcoma, did not improve outcomes [203].

Tumor cells expressing CD47 can be targeted with anti-CD47 monoclonal antibodies, which restore phagocytosis by macrophages and improve T-cell infiltration in RMS and osteosarcoma models [204,205]. Anti-PD-1 agents such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab and CTLA-4 blockade with ipilimumab have shown limited efficacy in pediatric sarcomas, with responses largely dependent on pre-treatment PD-L1 expression [206,207,208,209,210]. ARG1 and IDO1/2 inhibitors have demonstrated activity in adults, but pediatric trials are pending. Bevacizumab (anti-VEGF), combined with chemotherapy, has produced partial responses in refractory sarcomas, though rebound growth often occurs after discontinuation [211,212]. CSF1R inhibitors such as pexidartinib reduce TAM infiltration and improve T-cell function in early-phase trials [213].

5. Future Perspectives

The future of cancer therapy targeting the tumor microenvironment (TME) is evolving through a combination of molecular science, advanced nanomedicine, and artificial intelligence (AI [214]). New types of nanoparticles are being designed to respond to specific triggers, mimic natural cells, and actively eliminate tumor cells. These nanoplatforms deliver drugs more precisely, reduce off-target toxicity, and adapt to the dynamic nature of the tumor niche. Simultaneously, AI is enabling deep analysis of histopathology, genomics, and proteomics, helping in the identification of key biomarkers in prediction of treatment responses. Despite these advances, several challenges remain [215]. The TME is highly heterogeneous, and so are its components such as immune cells, stromal cells, and extracellular matrix. Ensuring safety and reproducibility of nanoparticle-based therapies, integrating AI tools into clinical workflows, and building diverse, high-quality datasets are ongoing hurdles [216,217,218]. As nanotechnology and AI continue to converge, they hold the potential to reshape cancer care, making it smarter, safer, and more responsive to the needs of each patient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., P.P., D.M. and A.S.; Methodology, S.B., P.P. and D.M.; Literature Review, S.B., P.P., D.M., N.G.G., N.G., B.R. and A.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, S.B., P.P., D.M. and A.S.; Writing—Review and Editing, N.G.G., N.G., B.R. and A.M.; Visualization, B.R. and A.M.; Supervision, A.S.; Project Administration, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. Ethical approval was not required as this study is a review article and does not involve human participants or patient data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. No human subjects or individual patient data were involved.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weber, C.E.; Kuo, P.C. The tumor microenvironment. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 21, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, A.S. Immune microenvironment in childhood cancers: Characteristics and therapeutic challenges. Cancers 2024, 16, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiovine, C.; Mebelli, K.; Raffaele, A.; De Cicco, M.; Rotella, J.; Pedrazzoli, P.; Zecca, M.; Riccipetitoni, G.; Comoli, P. Pediatric Solid Cancers: Dissecting the Tumor Microenvironment to Improve the Results of Clinical Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cancer in Children; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer-in-children (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Sultan, I.; Alfaar, A.S.; Sultan, Y.; Salman, Z.; Qaddoumi, I. Trends in childhood cancer: Incidence and survival analysis over 45 years of SEER data. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiaen, J.; Jacobs, S.A.; De Smet, F. The tumor micro-environment in pediatric glioma: Friend or foe? Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1227126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaskalani, O.; Abbas, Z.; Malinge, S.; Wouters, M.A.; Truong, J.; Johnson, I.M.; Kuster, J.; Nassar, A.; Wan, A.; Smolders, H.; et al. Age-dependent tumor-immune interactions underlie immunotherapy response in pediatric cancer. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, N.; Morris, L.; Havel, J.J.; Makarov, V.; Desrichard, A.; Chan, T.A. The role of neoantigens in response to immune checkpoint blockade. Int. Immunol. 2016, 28, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, J.; Bai, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, Q. Tumor microenvironment as a complex milieu driving cancer progression: A mini review. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 27, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S.M.A.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O’byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, M.; Schietinger, A. CD8+ T cell differentiation and dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togashi, Y.; Shitara, K.; Nishikawa, H. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression—Implications for anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Qin, S.; Si, W.; Wang, A.; Xing, B.; Gao, R.; Ren, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Pan-cancer single-cell landscape of tumor-infiltrating T cells. Science 2021, 374, abe6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumont, C.M.; Banville, A.C.; Gilardi, M.; Hollern, D.P.; Nelson, B.H. Tumour-infiltrating B cells: Immunological mechanisms, clinical impact and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, R.; Pollard, J.W. Tumor-associated macrophages: From mechanisms to therapy. Immunity 2014, 41, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L.; Pollard, J.W. A timeline of tumour-associated macrophage biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, N.R.; Applebaum, M.A.; Volchenboum, S.L.; Matthay, K.K.; London, W.B.; Ambros, P.F.; Nakagawara, A.; Berthold, F.; Schleiermacher, G.; Park, J.R.; et al. Advances in Risk Classification and Treatment Strategies for Neuroblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3008–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittet, M.J.; Michielin, O.; Migliorini, D. Clinical relevance of tumour-associated macrophages. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, I.S.; Ewald, A.J. The changing role of natural killer cells in cancer metastasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e143762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrimi, E.; Khan, N.; Murray, P.; Willcox, C.; Haigh, T.; Willcox, B.; Masand, N.; Bowen, C.; Dimakou, D.B.; Zuo, J.; et al. Defects in NK cell immunity of pediatric cancer patients revealed by deep immune profiling. iScience 2024, 27, 110837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaadt, T.; Ladenstein, R.L.; Ebinger, M.; Lode, H.N.; Arnardóttir, H.B.; Poetschger, U.; Schwinger, W.; Meisel, R.; Schuster, F.R.; Döring, M.; et al. Anti-GD2 antibody dinutuximab beta and low-dose interleukin 2 after haploidentical stem-cell transplantation in patients with relapsed neuroblastoma: A multicenter, phase I/II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3135–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, S. Tertiary lymphoid structures are critical for cancer prognosis and therapeutic response. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1063711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Sanseviero, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arina, A.; Idel, C.; Hyjek, E.M.; Alegre, M.-L.; Wang, Y.; Bindokas, V.P.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Schreiber, H. Tumor-associated fibroblasts predominantly come from local and not circulating precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7551–7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, G.; Tuveson, D.A. Diversity and biology of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brichkina, A.; Polo, P.; Sharma, S.D.; Visestamkul, N.; Lauth, M. A Quick Guide to CAF Subtypes in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: New findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.; Schöllhorn, A.; Schuhmacher, J.; Gouttefangeas, C. CAF-immune cell crosstalk and its impact in immunotherapy. Semin. Immunopathol. 2023, 45, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoschek, M.; Oskolkov, N.; Bocci, M.; Lövrot, J.; Larsson, C.; Sommarin, M.; Madsen, C.D.; Lindgren, D.; Pekar, G.; Karlsson, G.; et al. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siminzar, P.; Tohidkia, M.R.; Eppard, E.; Vahidfar, N.; Tarighatnia, A.; Aghanejad, A. Recent trends in diagnostic biomarkers of tumor microenvironment. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2023, 25, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011, 473, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynski, E.A.; Vermeulen, P.B.; Pezzella, F.; Kerbel, R.S.; Reynolds, A.R. Vessel co-option in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 469–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Peng, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, H.; Shan, B.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C. Vasculogenic mimicry in car-cainogenesis and clinical applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohba, T.; Cates, J.M.; Cole, H.A.; Slosky, D.A.; Haro, H.; Ando, T.; Schwartz, H.S.; Schoenecker, J.G. Autocrine VEGF/VEGFR1 signaling in a subpopulation of cells associates with aggressive osteosarcoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleuren, E.D.G.; Vlenterie, M.; van der Graaf, W.T.A. Recent advances on anti-angiogenic multi-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1013359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-A.; Li, X.-L.; Mo, Y.-Z.; Fan, C.-M.; Tang, L.; Xiong, F.; Guo, C.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, M.; Ma, J.; et al. Effects of tumor metabolic microen-vironment on regulatory T cells. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A.; Metcalf, K.J.; Werb, Z. Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattner, P.; Strobel, H.; Khoshnevis, N.; Grunert, M.; Bartholomae, S.; Pruss, M.; Fitzel, R.; Halatsch, M.-E.; Schilberg, K.; Siegelin, M.D.; et al. Compare and contrast: Pediatric cancer versus adult malignancies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019, 38, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, B. Extracellular matrix stiffness: Mechanisms in tumor progression and therapeutic potential in cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, C.M. Pediatric cancer—Pathology and microenvironment influence: A perspective into osteosarcoma and non-osteogenic mesenchymal malignant neoplasms. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Ahn, K.J.; Biyik-Sit, R.; Chen, C.; Thadi, A.; Chen, C.-H.; Molina, W.; Lockhart, B.; Laetsch, T.; Surrey, L.; et al. Dissecting pediatric sarcoma microenvironment using single-cell and spatial multi-omics. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, B061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-L.; Chen, H.-H.; Zheng, L.-L.; Sun, L.-P.; Shi, L. Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.H.; Morgenstern, D.A.; Leruste, A.; Bourdeaut, F.; Davis, K.L. Checkpoint immunotherapy in pediatrics: Here, gone, and back again. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2022, 42, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Filho, A.; Piñeros, M.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Monnereau, A.; Bray, F. Epidemiological patterns of leukaemia in 184 countries: A population-based study. Lancet Haematol. 2018, 5, e14–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malczewska, M.; Kośmider, K.; Bednarz, K.; Ostapińska, K.; Lejman, M.; Zawitkowska, J. Recent advances in treatment options for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancers 2022, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Trivedi, R.; Lin, S.-Y. Tumor microenvironment: Barrier or opportunity towards effective cancer therapy. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, A.M.; Izraeli, S. Interleukin-7 signaling as a therapeutic target in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2017, 10, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Saito, Y.; Kuroki, Y.; Hijikata, A.; Takagi, M.; Tomizawa, D.; Eguchi, M.; Eguchi-Ishimae, M.; Kaneko, A.; et al. Identification of CD34+ and CD34− leukemia-initiating cells in MLL-rearranged human acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015, 125, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, A.; Klein, S.; Beider, K.; Burger, J.A.; Abraham, M. Role of CXCL12 and CXCR4 in the pathogenesis of hematological malig-nancies. Cytokine 2018, 109, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aster, J.C.; Pear, W.S.; Blacklow, S.C. The varied roles of Notch in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2017, 12, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, C.S.; Radtke, F. Notch as a tumour suppressor. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadillo, E.; Dorantes-Acosta, E.; Pelayo, R.; Schnoor, M. T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL): New insights into the cellular origins and infiltration mechanisms common and unique among hematologic malignancies. Blood Rev. 2018, 32, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, D.; Di Tullio, A.; Abarrategi, A.; Rouault-Pierre, K.; Foster, K.; Ariza-McNaughton, L.; Montaner, B.; Chakravarty, P.; Bhaw, L.; Diana, G.; et al. Increased Vascular Permeability in the Bone Marrow Microenvironment Contributes to Disease Progression and Drug Response in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 324–341.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Wang, J.; Lu, T.; Ma, D.; Wei, D.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, B.; Wang, W.; Fang, Q. Overexpression of heme oxygenase-1 in microenvi-ronment mediates vincristine resistance of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia by promoting vascular endothelial growth factor secretion. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 17791–17810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, E.B.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxic control of metastasis. Science 2016, 352, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manesh, D.M.; El-Hoss, J.; Evans, K.; Richmond, J.; Toscan, C.E.; Bracken, L.S.; Hedrick, A.; Sutton, R.; Marshall, G.M.; Wilson, W.R.; et al. AKR1C3 is a biomarker of sensitivity to PR-104 in preclinical models of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2015, 126, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, B.P.; Nguyen, P.L.; Lee, K.; Cho, J. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1: A Novel Therapeutic Target for the Management of Cancer, Drug Resistance, and Cancer-Related Pain. Cancers 2022, 14, 6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.Z.; Desantis, G.; Janji, B.; Hasmim, M.; Karray, S.; Dessen, P.; Bronte, V.; Chouaib, S. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1a, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, S.; Laubach, J.P.; Hideshima, T.; Chauhan, D.; Anderson, K.C.; Richardson, P.G. The proteasome and proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 36, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, K.J.; Guest, E.M.; Lewing, K.; Hays, J.A.; Gamis, A.S. Treatment of children with relapsed and refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia with mitoxantrone, vincristine, pegaspargase, dexamethasone, and bortezomib. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouri, M.; Safaroghli-Azar, A.; Pourbagheri-Sigaroodi, A.; Momeny, M.; Bashash, D. Anti-leukemic effects of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells: Shedding light on mitigating effects of NF-kappaB and autophagy on panobinostat cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 875, 173050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Inukai, T.; Imamura, T.; Yano, M.; Tomoyasu, C.; Lucas, D.M.; Nemoto, A.; Sato, H.; Huang, M.; Abe, M.; et al. Anti-leukemic activity of bortezomib and carfilzomib on B-cell precursor ALL cell lines. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.; Lee, M.-E.; Lin, P.-C. A review of childhood acute myeloid leukemia: Diagnosis and novel treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersdorf, S.H.; Kopecky, K.J.; Slovak, M.; Willman, C.; Nevill, T.; Brandwein, J.; Larson, R.A.; Erba, H.P.; Stiff, P.J.; Stuart, R.K.; et al. A Phase 3 Study of Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin during Induction and Postconsolidation Therapy in Younger Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2013, 121, 4854–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hino, C.; Pham, B.; Park, D.; Yang, C.; Nguyen, M.H.; Kaur, S.; Reeves, M.E.; Xu, Y.; Nishino, K.; Pu, L.; et al. Targeting the tumor mi-croenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia: The future of immunotherapy and natural products. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Li, J.; Niu, T. A review of efficacy and safety of checkpoint inhibitor for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, M.S.; Kim, H.T.; Costello, C.; Herrera, A.F.; Locke, F.L.; Maegawa, R.O.; Savell, A.; Mazzeo, M.; Anderson, A.; Boardman, A.P.; et al. A multicenter phase 1 study of nivolumab for relapsed hematologic malignancies after allogeneic transplantation. Blood 2020, 135, 2182–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussai, F.; De Santo, C.; Abu-Dayyeh, I.; Booth, S.; Quek, L.; McEwen-Smith, R.M.; Qureshi, A.; Dazzi, F.; Vyas, P.; Cerundolo, V. Acute myeloid leukemia creates an arginase-dependent immunosuppressive microenvironment. Blood 2013, 122, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendker, S.; Reinhardt, D.; Niktoreh, N. Redirecting the immune microenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers 2021, 13, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringaris, K.; Sekine, T.; Khoder, A.; Alsuliman, A.; Razzaghi, B.; Sargeant, R.; Pavlu, J.; Brisley, G.; de Lavallade, H.; Sarvaria, A.; et al. Leukemia-induced phenotypic and functional defects in natural killer cells predict failure to achieve remission in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2014, 99, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aru, B.; Pehlivanoğlu, C.; Dal, Z.; Dereli-Çalışkan, N.N.; Gürlü, E.; Yanıkkaya-Demirel, G. A potential area of use for immune checkpoint inhibitors: Targeting bone marrow microenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1108200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Basu, S.; Boddu, P.C.; Alfayez, M.; Cortes, J.E.; Konopleva, M.; Ravandi-Kashani, F.; Jabbour, E.; Kadia, T.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Biomarkers of Response to Azacitidine and Nivolumab in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Nonrandomized, Open-Label, Phase II Study. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uckun, F.M.; Lin, T.L.; Mims, A.S.; Patel, P.; Lee, C.; Shahidzadeh, A.; Shami, P.J.; Cull, E.; Cogle, C.R.; Watts, J. A Clinical Phase 1B Study of the CD3xCD123 Bispecific Antibody APVO436 in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia or Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Cancers 2021, 13, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Z.; Busfield, S.; Ritchie, D.S.; Hertzberg, M.S.; Durrant, S.; Lewis, I.D.; Marlton, P.; McLachlan, A.J.; Kerridge, I.; Bradstock, K.F.; et al. A Phase 1 study of the safety, pharmacokinetics and anti-leukemic activity of the anti-CD123 monoclonal antibody CSL360 in relapsed, refractory or high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Padmanabhan, I.S.; Parmar, S.; Gong, Y. Targeting CLL-1 for acute myeloid leukemia therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Meng, Y.; Yao, H.; Zhan, R.; Chen, S.; Miao, W.; Ma, S.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Yu, M.; et al. CAR-NK cells for acute myeloid leukemia immunotherapy: Past, present and future. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2023, 13, 5559–5576. [Google Scholar]

- Bachanova, V.; Sarhan, D.; DeFor, T.E.; Cooley, S.; Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A.; Blazar, B.R.; Curtsinger, J.M.; Burns, L.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Miller, J.S. Haploidentical natural killer cells induce remissions in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients with low levels of immune-suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.S.; Morishima, C.; McNeel, D.G.; Patel, M.R.; Kohrt, H.E.; Thompson, J.A.; Sondel, P.M.; Wakelee, H.A.; Disis, M.L.; Kaiser, J.C.; et al. A First-in-Human Phase I Study of Subcutaneous Outpatient Recombinant Human IL15 (rhIL15) in Adults with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, T.W.; Williams, R.O. Interactions of IDO and the Kynurenine Pathway with Cell Transduction Systems and Metabolism at the Inflammation-Cancer Interface. Cancers 2023, 15, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, C.; Stravokefalou, V.; Stellas, D.; Karaliota, S.; Felber, B.K.; Pavlakis, G.N. Heterodimeric IL-15 in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosna, F. The Immunotherapy of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Clinical Point of View. Cancers 2024, 16, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.; Barth, M.; Armenian, S.; Audino, A.N.; Barnette, P.; Cuglievan, B.; Ding, H.; Ford, J.B.; Galardy, P.J.; Gardner, R.; et al. Pediatric Aggressive Mature B-Cell Lymphomas, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 1105–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X. Targeting the tumor microenvironment in B-cell lymphoma: Challenges and opportunities. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaoui, I.; Uhel, F.; Rossille, D.; Pangault, C.; Dulong, J.; Le Priol, J.; Lamy, T.; Houot, R.; Le Gouill, S.; Cartron, G.; et al. T-cell defect in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas involves expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood 2016, 128, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfroi, B.; Moreaux, J.; Righini, C.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Sturm, N.; Huard, B. Tumor-associated neutrophils correlate with poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cózar, B.; Greppi, M.; Carpentier, S.; Narni-Mancinelli, E.; Chiossone, L.; Vivier, E. Tumor-Infiltrating Natural Killer Cells. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papin, A.; Tessoulin, B.; Bellanger, C.; Moreau, A.; Le Bris, Y.; Maisonneuve, H.; Moreau, P.; Touzeau, C.; Amiot, M.; Pellat-Deceunynck, C.; et al. CSF1R and BTK inhibitions as novel strategies to disrupt the dialog between mantle cell lymphoma and macrophages. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2442–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ji, J.; Xu, J.; Li, D.; Shi, G.; Liu, F.; Ding, L.; Ren, J.; Dou, H.; Wang, T.; et al. MiR-30a increases MDSC differentiation and immu-nosuppressive function by targeting SOCS3 in mice with B-cell lymphoma. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 2410–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, N.G.; Herndler-Brandstetter, D.; Weiskopf, K.; Shan, L.; Volkmer, J.-P.; George, B.M.; Lietzenmayer, M.; McKenna, K.M.; Naik, T.J.; McCarty, A.; et al. Anti-SIRPα antibody immunotherapy enhances neutrophil and macrophage antitumor activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E10578–E10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohrt, H.E.; Thielens, A.; Marabelle, A.; Sagiv-Barfi, I.; Sola, C.; Chanuc, F.; Fuseri, N.; Bonnafous, C.; Czerwinski, D.; Rajapaksa, A.; et al. Anti-KIR antibody enhancement of anti-lymphoma activity of natural killer cells as monotherapy and in combination with anti-CD20 antibodies. Blood 2014, 123, 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Hill, H.; Christie, A.; Kim, M.S.; Holloman, E.; Pavia-Jimenez, A.; Homayoun, F.; Ma, Y.; Patel, N.; Yell, P.; et al. Targeting renal cell carcinoma with a HIF-2 antagonist. Nature 2016, 539, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.S.; Weirather, J.L.; Lipschitz, M.; Lako, A.; Chen, P.-H.; Griffin, G.K.; Armand, P.; Shipp, M.A.; Rodig, S.J. The microenvironmental niche in classic Hodgkin lymphoma is enriched for CTLA-4-positive T cells that are PD-1-negative. Blood 2019, 134, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, I.; Diaconu, I.; Dotti, G. From monoclonal antibodies to chimeric antigen receptors for the treatment of human malignancies. Semin. Oncol. 2014, 41, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, J.M.; Mauz-Korholz, C.; Hernandez, T.; Milgrom, S.A.; Castellino, S.M. Pediatric and Adolescent Hodgkin Lymphoma: Paving the Way for Standards of Care and Shared Decision Making. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2024, 44, e432420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusconi, C.; Ciavarella, S.; Fabbri, A.; Flenghi, L.; Puccini, B.; Re, A.; Sorio, M.; Vanazzi, A.; Zanni, M. Treatment of very high-risk classical Hodgkin Lymphoma: Cases’ selection from real life and critical review of the literature. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, P.; Descalzi-Montoya, D.B.; Lodhi, N. The circuitry of the tumor microenvironment in adult and pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma: Cellular composition, cytokine profile, EBV, and exosomes. Cancer Rep. 2021, 4, e1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgoulis, V.; Papoudou-Bai, A.; Makis, A.; Kanavaros, P.; Hatzimichael, E. Unraveling the Immune Microenvironment in Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma: Prognostic and Therapeutic Implications. Biology 2023, 12, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, P.; Clear, A.; Owen, A.; Iqbal, S.; Lee, A.; Matthews, J.; Wilson, A.; Calaminici, M.; Gribben, J.G. Defining characteristics of classical Hodgkin lymphoma microenvironment T-helper cells. Blood 2013, 122, 2856–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaddanapudi, K.; Putty, K.; Rendon, B.E.; Lamont, G.J.; Faughn, J.D.; Satoskar, A.; Lasnik, A.; Eaton, J.W.; Mitchell, R.A. Control of tumor-associated macrophage alternative activation by macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 2984–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guidetti, A.; Mazzocchi, A.; Miceli, R.; Paterno’, E.; Taverna, F.; Spina, F.; Crippa, F.; Farina, L.; Corradini, P.; Gianni, A.; et al. Early reduction of serum TARC levels may predict for success of ABVD as frontline treatment in patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma. Leuk. Res. 2017, 62, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SoRelle, E.D.; Haynes, L.E.; Willard, K.A.; Chang, B.; Ch’NG, J.; Christofk, H.; Luftig, M.A. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation induces di-vergent abortive, reprogrammed, and host shutoff states by lytic progression. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, R.G.; Wilson, J.B.; Anderson, S.J.; Longnecker, R. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A drives B cell development and survival in the absence of normal B cell receptor signals. Immunity 1998, 9, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Schips, J.; Granai, M.; Quintanilla-Martinez, L.; Fend, F. The Grey Zones of Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Du, L.M.; Cao, K.; Huang, Y.; Yu, P.F.; Zhang, L.Y.; Li, F.Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.F. Tumour cell-derived exosomes endow mesenchymal stromal cells with tumour-promotion capabilities. Oncogene 2016, 35, 6038–6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, H.P.; Engels, H.M.; Dams, M.; Paes Leme, A.F.; Pauletti, B.A.; Simhadri, V.L.; Dürkop, H.; Reiners, K.S.; Barnert, S.; Engert, A.; et al. Protrusion-guided extracellular vesicles mediate CD30 trans-signalling in the micro-environment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Pathol. 2014, 232, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuruvilla, J.; Ramchandren, R.; Santoro, A.; Paszkiewicz-Kozik, E.; Gasiorowski, R.; Johnson, N.A.; Fogliatto, L.M.; Goncalves, I.; de Oliveira, J.S.R.; Buccheri, V.; et al. KEYNOTE-204 investigators. Pembrolizumab versus brentuximab vedotin in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (KEYNOTE-204): An interim analysis of a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 512–524, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, e184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00193-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramchandren, R.; Domingo-Domènech, E.; Rueda, A.; Trněný, M.; Feldman, T.A.; Lee, H.J.; Provencio, M.; Sillaber, C.; Cohen, J.B.; Savage, K.J.; et al. Nivolumab for Newly Diagnosed Advanced-Stage Classic Hodgkin Lymphoma: Safety and Efficacy in the Phase II CheckMate 205 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröckelmann, P.J.; Bühnen, I.; Meissner, J.; Trautmann-Grill, K.; Herhaus, P.; Halbsguth, T.V.; Schaub, V.; Kerkhoff, A.; Mathas, S.; Bormann, M.; et al. Nivolumab and doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine in early-stage unfavorable Hodgkin lymphoma: Final analysis of the randomized German Hodgkin Study Group phase II NIVAHL trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.F.; LeBlanc, M.; Castellino, S.M.; Li, H.; Rutherford, S.C.; Evens, A.M.; Davison, K.; Punnett, A.; Parsons, S.K.; Ahmed, S.; et al. Nivolumab + AVD in advanced-stage classic Hodg-kin’s lymphoma. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diefenbach, C.S.; Hong, F.; Ambinder, R.F.; Cohen, J.B.; Robertson, M.J.; David, K.A.; Advani, R.H.; Fenske, T.S.; Barta, S.K.; Palmisiano, N.D.; et al. Ipilimumab, nivolumab, and brentuximab vedotin combination therapies in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: Phase 1 results of an open-label, multicentre, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e660–e670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-Y.; Collins, G.P. Checkpoint inhibitors and the changing face of the relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma pathway. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, M.S.; Naranjo, A.; Zhang, F.F.; Cohn, S.L.; London, W.B.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Ramirez, N.C.; Pfau, R.; Reshmi, S.; Wagner, E.; et al. Revised Neuroblastoma Risk Classification System: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3229–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystal, J.; Foster, J.H. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma. Children 2023, 10, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. Targeting the tumor microenvironment in neuroblastoma: Recent advances and future directions. Cancers 2020, 12, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louault, K.; De Clerck, Y.A.; Janoueix-Lerosey, I. The neuroblastoma tumor microenvironment: From an in-depth characterization towards novel therapies. EJC Paediatr. Oncol. 2024, 3, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaafsma, E.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, C. B cell infiltration is highly associated with prognosis and an immune-infiltrated tumor mi-croenvironment in neuroblastoma. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Li, T.; Xiao, J.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Niu, H.; Jiang, B.; Huang, L.; Deng, X.; Yan, X.; et al. Tumor Microenvironment Profiling Identifies Prognostic Signatures and Suggests Immunotherapeutic Benefits in Neuroblastoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 814836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaiu, O.; Chierici, M.; Lucarini, V.; Jurman, G.; Conti, L.A.; De Vito, R.; Boldrini, R.; Cifaldi, L.; Castellano, A.; Furlanello, C.; et al. Cellular and gene signatures of tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells and natural-killer cells predict prognosis of neuroblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]