Targeted Biological Therapy and Germline Mutation Prevalence in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

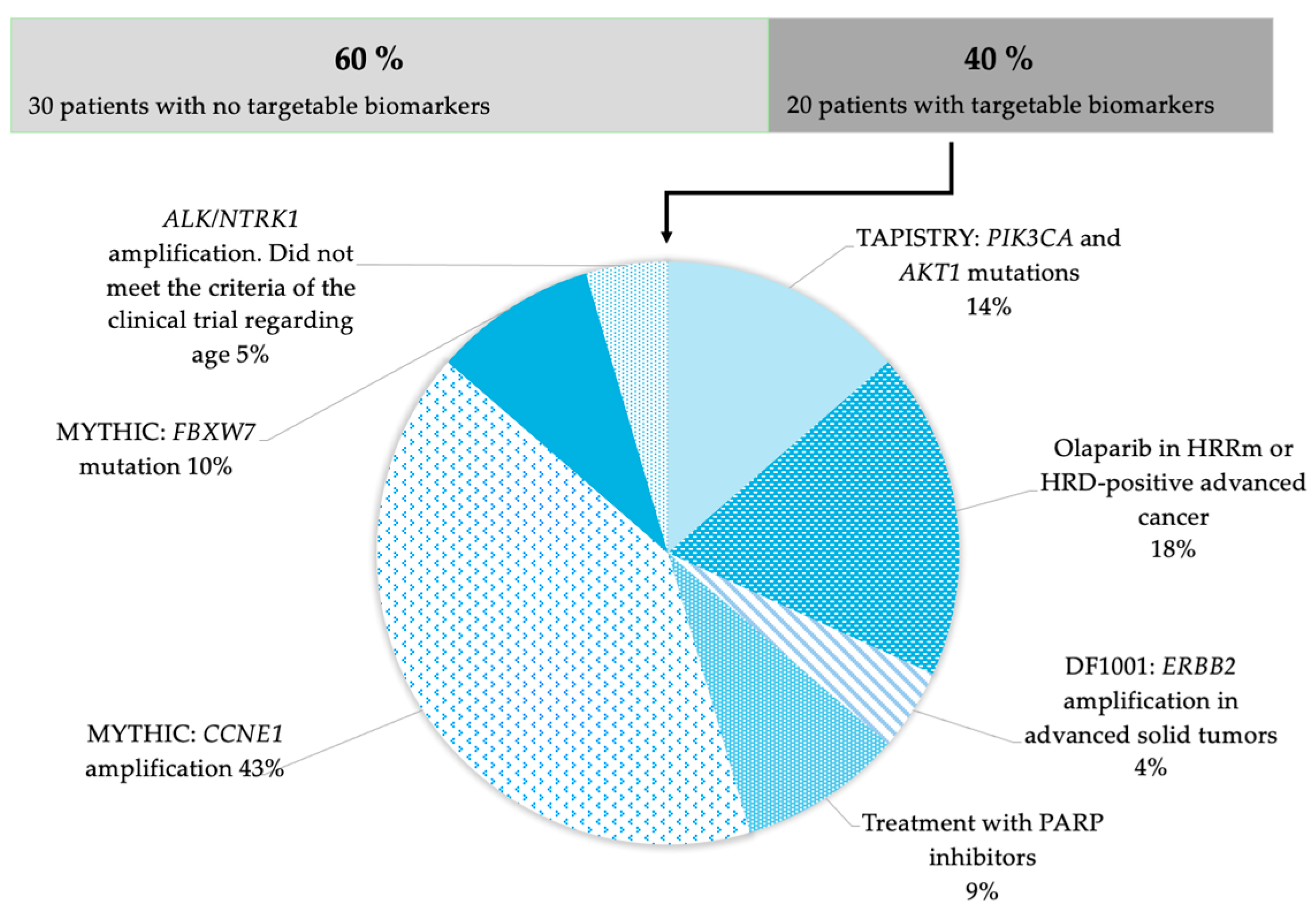

2.2. Sequencing Results of Tumor Samples

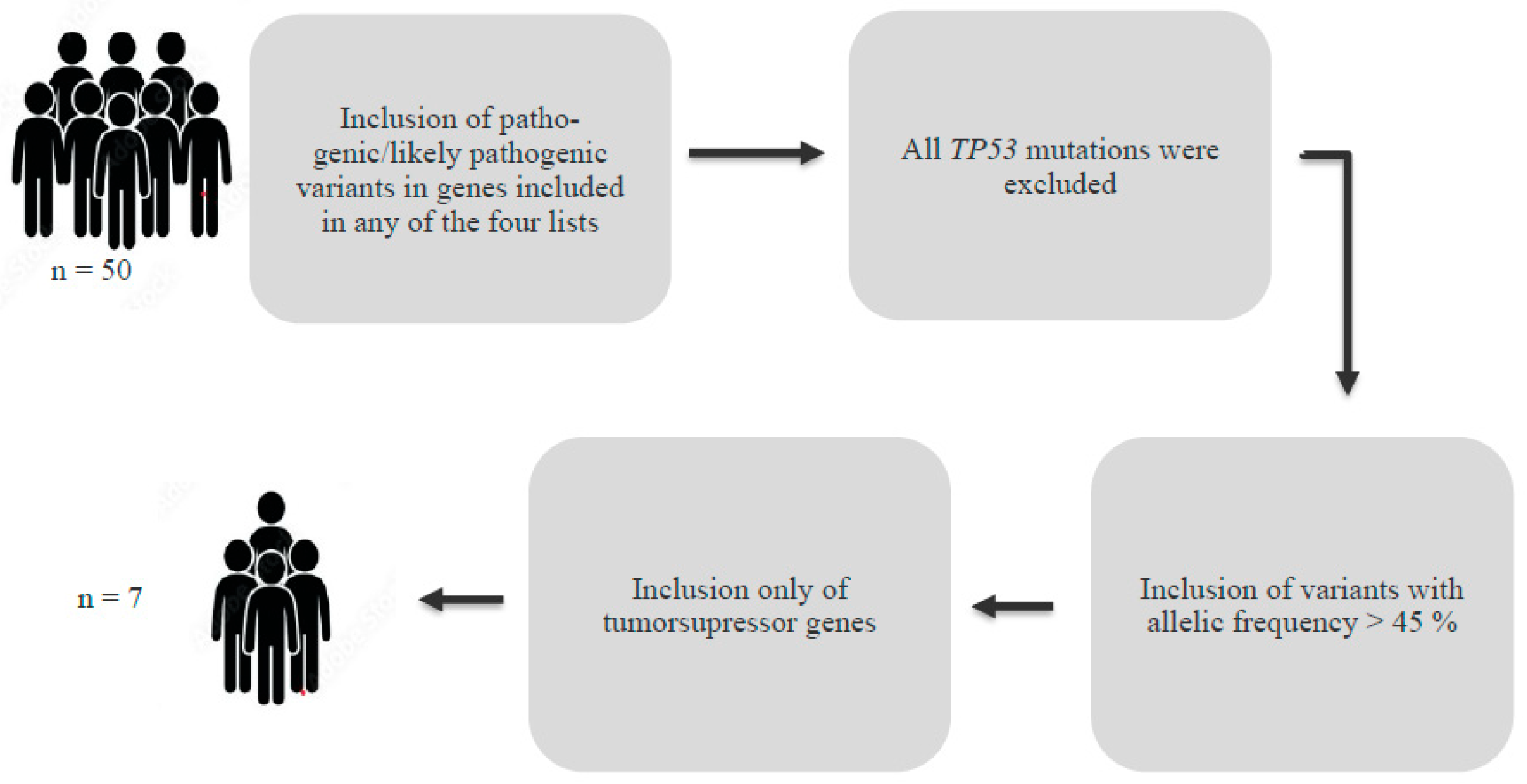

2.3. Germline Mutations

3. Results

Germline Mutations

4. Discussion

Limitations and Advantages

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lheureux, S.; Braunstein, M.; Oza, A.M. Epithelial ovarian cancer: Evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology. FIGO-Ovarian-Cancer-Staging_1.10.14. 2014. Available online: https://www.sgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/FIGO-Ovarian-Cancer-Staging_1.10.14.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Kumar, V.; Abbas, A.K. Basic Pathology, 11th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 614–618. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Norquist, B.; Lacchetti, C.; Armstrong, D.; Grisham, R.N.; Goodfellow, P.J.; Kohn, E.C.; Levine, D.A.; Liu, J.F.; Lu, K.H.; et al. Germline and Somatic Tumor Testing in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1222–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. 2024. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/brca-fact-sheet (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Roed Nielsen, H. Hereditaer Disposition Til Ovariecancer, HOC Dansk Selskab for Medicinsk Genetik (DSMG) Guideline. 2019. Available online: https://dsmg.dk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Hereditaer-disposition-til-ovariecancer-HOC.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Mosgaard, B.; Pedersen, L.; Mikkelsen, M. Kirurgisk Behandling af Epiteliale Ovarietumorer. 2024. Available online: https://www.dgcg.dk/images/retningslinier/Ovariecancer/DGCG_kir_beh_epi_ovari_v3.2_AdmGodk_190624.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Mosgaard, B.; Pedersen, L.; Bjørn, S. Ovariecancer—Medicinsk Behandling af Primær Ovariecancer Stadie I-IIA. 2022. Available online: https://www.dgcg.dk/images/retningslinier/Ovariecancer/DGCG_Med_beh_primr_c_ovarii_stadie%20I-IIA%20_v2.0_AdmGodk_031025.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Hæe, M.; Raza Mizar, M. Ovariecancer—Medicinsk Behandling af Primær Ovariecancer Stadie IIB-IV. 2023. Available online: https://www.dgcg.dk/images/retningslinier/Ovarie/DGCG_Med_beh_c_ovarie%20IIIb-IV_V.%202.0_AdmGodk_100125.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Høgdall, E.; Steniche, T. Ovariecancer: BRCA1/2 og HRD-Testning Med Henblik på Selektion af Patienter til PARP-Hæmmer Behandling. 2023. Available online: https://www.dgcg.dk/images/retningslinier/Ovariecancer/DGCG_BRCA12_HRD_testning_ovariecancer_V.1.0_AdmGodk_0201235719.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Herlev Hospital. Fase 1 Behandlingsforsøg. Available online: https://www.herlevhospital.dk/undersoegelse-og-behandling/find-undersoegelse-og-behandling/Sider/Fase-1-behandlingsforsoeg-23217.aspx (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Key Highlights of the Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus. 2024. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/dk/en/home/clinical/preclinical-companion-diagnostic-development/oncomine-oncology/oncomine-cancer-research-panel-workflow/oncomine-comprehensive-assay-plus.html (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghezelayagh, T.S.; Pennington, K.P.; Norquist, B.M.; Khasnavis, N.; Radke, M.R.; Kilgore, M.R.; Garcia, R.L.; Lee, M.; Katz, R.; Leslie, K.K.; et al. Characterizing TP53 mutations in ovarian carcinomas with and without concurrent BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 160, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzbari, Z.; Bandlamudi, C.; Loveday, C.; Garrett, A.; Mehine, M.; George, A.; Hanson, H.; Snape, K.; Kulkarni, A.; Allen, S.; et al. Germline-focused analysis of tumour-detected variants in 49,264 cancer patients: ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group recommendations. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au-Yeung, G.; Mileshkin, L.; Bowtell, D.D. CCNE1 Amplification as a Therapeutic Target. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repare Therapeutics Study of RP-6306 Alone or in Combination with RP-3500 or Debio 0123 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors (MYTHIC). NIH; April 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04855656 (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- COSMIC CNV—Overview. 2010. Available online: https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/help/cnv/overview (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Hoffmann-La, R. Tumor-Agnostic Precision Immuno-Oncology and Somatic Targeting Rational for You (TAPISTRY) Platform Study. 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04589845 (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Merck, S.; Dohme, L. Efficacy and Safety of Olaparib (MK-7339) in Participants with Previously Treated, Homologous Recombination Repair Mutation (HRRm) or Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Positive Advanced Cancer (MK-7339-002/LYNK-002). NIH; August 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03742895 (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Dragonfly Therapeutics Study of DF1001 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. NIH; January 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04143711#collaborators-and-investigators (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Auguste, A.; Blanc-Durand, F.; Deloger, M.; Le Formal, A.; Bareja, R.; Wilkes, D.C.; Richon, C.; Brunn, B.; Caron, O.; Devouassoux-Shisheboran, M.; et al. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary, Hypercalcemic Type (SCCOHT) beyond SMARCA4 Mutations: A Comprehensive Genomic Analysis. Cells 2020, 9, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.; Karnezis, A.N.; Craig, D.W.; Sekulic, A.; Russell, M.L.; Hendricks, W.P.D.; Corneveaux, J.J.; Barrett, M.T.; Shumansky, K.; Yang, Y.; et al. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type, displays frequent inactivating germline and somatic mutations in SMARCA4. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Phelan, C.M.; Zhang, P.; Rousseau, F.; Ghadirian, P.; Robidoux, A.; Foulkes, W.; Hamel, N.; McCready, D.; Trudeau, M.; et al. Frequency of the CHEK2 1100delC mutation among women with breast cancer: An international study. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 2154–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarova, L.; Kleiblova, P.; Janatova, M.; Soukupova, J.; Zemankova, P.; Macurek, L.; Kleibl, Z. CHEK2 Germline Variants in Cancer Predisposition: Stalemate Rather than Checkmate. Cells 2020, 9, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi-Fakhari, D.; Mann, L.L.; Poryo, M.; Graf, N.; Von Kries, R.; Heinrich, B.; Ebrahimi-Fakhari, D.; Flotats-Bastardas, M.; Gortner, L.; Zemlin, M.; et al. Incidence of tuberous sclerosis and age at first diagnosis: New data and emerging trends from a national, prospective surveillance study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovby, F.; Larsen, E.P. Neurofibromatose Type 2. 2023. Available online: https://www.sundhed.dk/sundhedsfaglig/laegehaandbogen/sjaeldne-sygdomme/sjaeldne-sygdomme/neurofibromatose-type-2/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Gorski, J.W.; Ueland, F.R.; Kolesar, J.M. CCNE1 amplification as a predictive biomarker of chemotherapy resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repare Therapeutics Announces Positive Results of the Lunresertib and Camonsertib Combination from the MYTHIC Phase 1 Gynecologic Expansion Clinical Trial. 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/company/repare-therapeutics/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Kinnersley, B.; Sud, A.; Everall, A.; Cornish, A.J.; Chubb, D.; Culliford, R.; Gruber, A.J.; Lärkeryd, A.; Mitsopoulos, C.; Wedge, D.; et al. Analysis of 10,478 cancer genomes identifies candidate driver genes and opportunities for precision oncology. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 1868–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosele, M.F.; Westphalen, C.B.; Stenzinger, A.; Barlesi, F.; Bayle, A.; Bièche, I.; Bonastre, J.; Castro, E.; Dienstmann, R.; Krämer, A.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: A report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callegaro-Filho, D.; Gershenson, D.M.; Nick, A.M.; Munsell, M.F.; Ramirez, P.T.; Eifel, P.J.; Euscher, E.D.; Marques, R.M.; Nicolau, S.M.; Schmeler, K.M.; et al. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary-hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT): A review of 47 cases. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 140, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aedma, S.K.; Kasi, A.; Affiliations, K.; Fraumeni, L. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome Continuing Education Activity; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532286/?report=printable (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- O’Malley, D.M.; Krivak, T.C.; Kabil, N.; Munley, J.; Moore, K.N. PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer: A Review. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 471–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | Copy Number Variation |

|---|---|

| 37 | 7 |

| 33 | 8 |

| 18 | 9 |

| 14 | 10 |

| 10 | 10 |

| 6 | 16 |

| 8 | 21 |

| 11 | 28 |

| 31 | 104 |

| P. | Mutation | HRD Status |

|---|---|---|

| 14 | CHEK2 p.(T367Mfs*15) c.1100delC | Negative |

| 15 | CDK12 p.(G1092Afs*11) c.3275delG | Negative |

| 25 | PALB2 p.(S565I) c.1694G>T | Negative |

| 36 | CDK12 p.(S318Lfs*20) c.952delT | Negative |

| Patient | Variant (Mutation) | Gene Type | Possible Association with Predisposition to Ovarian Cancer | Allelic Frequency (%) | Tumor Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | SMARCA4 | Tumor supressor | Yes | 54 | 56 |

| 14 | CHEK2 | Tumor supressor | Uncertain | 76 | 40 |

| 17 | NF2 | Tumor supressor | No | 54 | 60 |

| 30 | BRCA1 | Tumor supressor | Yes | 70 | 50 |

| 32 | TSC1 | Tumor supressor | No | 45 | 30 |

| 41 | BRCA2 | Tumor supressor | Yes | 47 | 72 |

| 48 | TSC1 | Tumor supressor | No | 45 | 51 |

Hospitals 1, 2, 3 and 4;

Hospitals 1, 2, 3 and 4;  Hospitals 1 and 2;

Hospitals 1 and 2;  Hospitals 1, 2 and 3.

Hospitals 1, 2 and 3.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ellegaard, A.-M.M.; Poulsen, T.S.; Høgdall, E. Targeted Biological Therapy and Germline Mutation Prevalence in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients. Onco 2025, 5, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5040052

Ellegaard A-MM, Poulsen TS, Høgdall E. Targeted Biological Therapy and Germline Mutation Prevalence in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients. Onco. 2025; 5(4):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleEllegaard, Anne-Marie Mosbæk, Tim Svenstrup Poulsen, and Estrid Høgdall. 2025. "Targeted Biological Therapy and Germline Mutation Prevalence in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients" Onco 5, no. 4: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5040052

APA StyleEllegaard, A.-M. M., Poulsen, T. S., & Høgdall, E. (2025). Targeted Biological Therapy and Germline Mutation Prevalence in Advanced Ovarian Cancer Patients. Onco, 5(4), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/onco5040052