1. Introduction

Transport systems play a vital role in facilitating access to essential services, employment, and social participation. However, in rural areas where infrastructure is often sparse and underdeveloped [

1,

2], people with disabilities continue to face disproportionate barriers in mobility [

3,

4]. For people with disabilities, accessible transport is not merely a convenience but a requirement for exercising basic human rights and achieving social inclusion [

5,

6]. Yet in South Africa and many other African countries, rural transport continues to be fraught with challenges that disproportionately affect people with disabilities.

The South African rural transport system is characterized by limited infrastructure, uneven terrain and systematic neglect [

7,

8]. Gravel roads, potholes, and seasonal flooding frequently lead to rural routes being impassable, disproportionately affecting households located in valleys or remote settlements [

9,

10]. Due to the unfavourable characteristics of rural roads, minibus taxis are the primary means of transport for most rural communities, offering flexibility [

11]. Minibus taxis provide indispensable services to millions of South Africans, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas where formal public transport is absent. However, minibus taxis often lack the necessary accommodations for transporting people with disabilities, such as space for wheelchairs or trained personnel to assist with boarding and alighting [

12]. While minibus taxi drivers, are often empathetic, they operate within systemic constraints that limit their capacity to provide inclusive service [

13].

Rural transport exclusion is not unique to South Africa. Research in Malawi, Uganda, and Pakistan demonstrates that inaccessible infrastructure and negative social attitudes consistently undermine mobility for passengers with disabilities [

5,

14,

15]. However, other studies extend understanding of socio-economic exclusion by highlighting additional, less visible forms of exclusion [

16,

17]. For example, financial exclusion occurs when people with disabilities are required to assess the ‘worth’ or affordability of transport services that should be guaranteed as social right. Exclusion is also linked to limited social support and lack of trustworthiness within transport systems which affects perceptions of safety, autonomy, self-dignity and personal security [

18,

19]. In Europe, despite stronger policy frameworks, rural residents with disabilities still report limited access to mainstream transport, highlighting the universality of the challenge [

20,

21]. Although transport barriers faced by people with disabilities are a global issue, African countries often find themselves in an even more challenging position due to inadequate infrastructure. Many rural areas lack the basic facilities needed for accessibility, such as ramps, elevators, and properly designed public transport systems.

Rural transport research in South Africa largely focuses on economic development and infrastructure provision, often overlooking the lived experiences of marginalised groups. For example, Pillay [

22] highlights poor road infrastructure as a barrier to rural development, but does not specifically address how people with disabilities are affected or how transport providers adapt to these challenges. Previous research has also examined passengers’ perspectives [

23,

24], but only a few studies have explored the drivers’ viewpoints, despite their central role in shaping accessibility outcomes. Drivers interact daily with passengers with disabilities in practical operating conditions, allowing them to identify operational constraints, interpersonal challenges, and situational barriers that may not be fully captured through passengers’ perspectives alone. The views of drivers help provide insights into the intersection of infrastructure, operational constraints, and human attitudes from a rural setting perspective. Drivers’ experiences complement users’ accounts and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of rural transport accessibility.

Therefore, this study aims to understand the experiences of minibus taxi drivers in transporting passengers with disabilities in Mt Elias, a rural community in KwaZulu-Natal. To address the aim of this study, the following objectives were formulated: (1) to identify the challenges experienced by minibus taxi drivers in providing transport services to passengers with disabilities in Mt Elias, and (2) to explore drivers’ views on transport infrastructure and services in a rural community.

The focus on minibus taxis in a rural setting directly addresses the mobility needs of people with disabilities, offering insights into operational, infrastructural, and attitudinal improvements that can enhance the inclusivity of transport systems. This study contributes to Sustainable Development Goal 11, Target 11.2, which calls for providing access to safe, affordable, accessible, and sustainable transport systems for all, with special attention to vulnerable groups [

25]. By documenting how transport challenges exclude people with disabilities, this study indirectly supports efforts to alleviate poverty and promote health equity. Drivers’ experiences, in this study contributes to a deeper understanding of rural transport dynamics and highlight the urgency of inclusive mobility as a matter of social justice and human rights.

3. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in Dalton, a small town centre in uMshwathi municipality in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Dalton serves as a key service hub for surrounding rural communities, including Mt Elias, where residents regularly travel to shop, access banking services, and collect monthly social grants.

3.1. Interview Guide Development

The semi-structured interviews were designed to address two objectives: (1) to identify the challenges experienced by minibus taxi drivers in providing transport services to passengers with disabilities in Mt Elias, and (2) to explore drivers’ views on transport infrastructure and services in a rural community. The semi-structured interview guide was developed by the author, drawing on both empirical literature and conceptual frameworks related to disability, transport accessibility, and rural mobility. The guide included open-ended questions focusing on drivers’ daily practices, challenges encountered when assisting passengers with disabilities, perceptions of transport infrastructure, and interactions with passengers and co-passengers. The interview guide was informed by existing literature on disability and transport accessibility and aligned with the study objectives. Prior to data collection, the interview guide was piloted with one minibus taxi driver operating in a similar rural context but not included in the final sample. Feedback from the pilot led to minor revisions, including simplifying question wording and improving question flow. To ensure clarity and validity, questions were aligned with the study objectives and reviewed to ensure they were understandable, contextually appropriate, and capable of eliciting rich, experience-based data.

3.2. Recruitment and Participation

The participants were 15 minibus taxi drivers who operate specifically on the Dalton to Mt Elias route. These drivers were purposively selected based on their direct involvement in transporting passengers in rural settings, ensuring that the data collected was contextually rich and relevant. A qualitative research method was employed, using semi-structured interviews to explore the lived experiences of drivers. This approach provided in-depth insights into the challenges and practices surrounding the transportation of passengers with disabilities in rural communities. Purposive sampling was used to identify participants with firsthand experience, aligning with recommendations on selecting information-rich cases [

46]. Although qualitative research does not require large samples, the selection of 15 participants was guided by methodological literature emphasizing depth over breadth [

47,

48]. Data saturation was reached at Driver 9, as no new themes emerged beyond this point. However, interviews continued up to Driver 15 to strengthen the reliability of the findings and serve as a control measure. Saturation is a key concept in qualitative research, indicating the point at which additional data no longer contributes new insights [

49,

50,

51]. Continuing beyond saturation is supported by methodological guidance to ensure analytical completeness and confirm thematic consistency [

52,

53].

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured, face-to-face interviews conducted at Dalton taxi rank. Interviews were conducted in a familiar environment to facilitate open discussion and minimize disruption to drivers’ work routines. Each interview lasted approximately 30–45 min and was conducted in the participants’ preferred language. With participants’ consent, interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim for analysis. Data collection continued until thematic saturation was reached, which occurred at Driver 9; however, interviews proceeded to Driver 15 to confirm consistency and enhance the robustness of the findings.

The study was conducted within the South African minibus taxi industry, a sector widely recognized for its highly sensitive operating environment, characterized by longstanding issues of violence, territorial control, and deep-seated mistrust of outsiders. Access to participants is extremely limited, and prolonged engagement is often neither feasible nor safe. In this case, permission to conduct interviews was granted only for a single day, under strict conditions imposed by the Taxi Association. Extending the data collection beyond this timeframe was not possible. Importantly, the interviews were not conducted by a single researcher in isolation. The lead researcher was supported by two trained research assistants and local intermediaries who were familiar with the industry and trusted by participants. This approach mitigated interviewer fatigue, enabling the interviews to be conducted efficiently while maintaining consistency in questioning.

Table 1 presents the background information, key drivers, duration of the interviews.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis, following the six-phase approach outlined by Braun and Clarke [

52]. This method provided a systematic approach for identifying, organizing, and interpreting patterns of meaning across the dataset. Transcripts were imported into ATLAS.ti, where initial codes were generated inductively from the data. The author first familiarised herself with the data through repeated reading of transcripts to gain an overall understanding of the content. The codes were then grouped into broader categories and refined into themes that captured the core experiences of minibus taxi drivers. Visual tools within ATLAS.ti version 25, such as treemaps and Sankey diagrams, were used to illustrate the frequency and relationships between codes, enhancing both analytical depth and presentation clarity [

54]. This procedure made sure that the conclusions were supported by the data while enabling a more complex understanding of the drivers’ viewpoints.

Credibility and trustworthiness were supported through a systematic and transparent analytic process. The researcher engaged in repeated familiarization with the transcripts, and analytic decisions were documented throughout coding, category refinement, and theme development, creating an audit trail. The analysis was conducted by a single researcher; therefore, inter-coder reliability measures were not applicable. Instead, rigor was enhanced through iterative comparison of codes and themes across the dataset and continuous reference to the original transcripts to ensure interpretations remained grounded in participants’ accounts. ATLAS.ti was used to support data management and to explore code frequency and co-occurrence patterns.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance for this study was granted by the Department of Transport and Supply Chain Management Ethics Committee at the University of Johannesburg. Prior to participation, each driver provided consent after being informed of the study’s objectives. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the research process. The study adhered to ethical principles of voluntary participation and respect, as outlined by De Vos [

55] ensuring that the voices of drivers were represented with integrity and care. Participation was voluntary, and drivers were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage without consequence.

4. Results

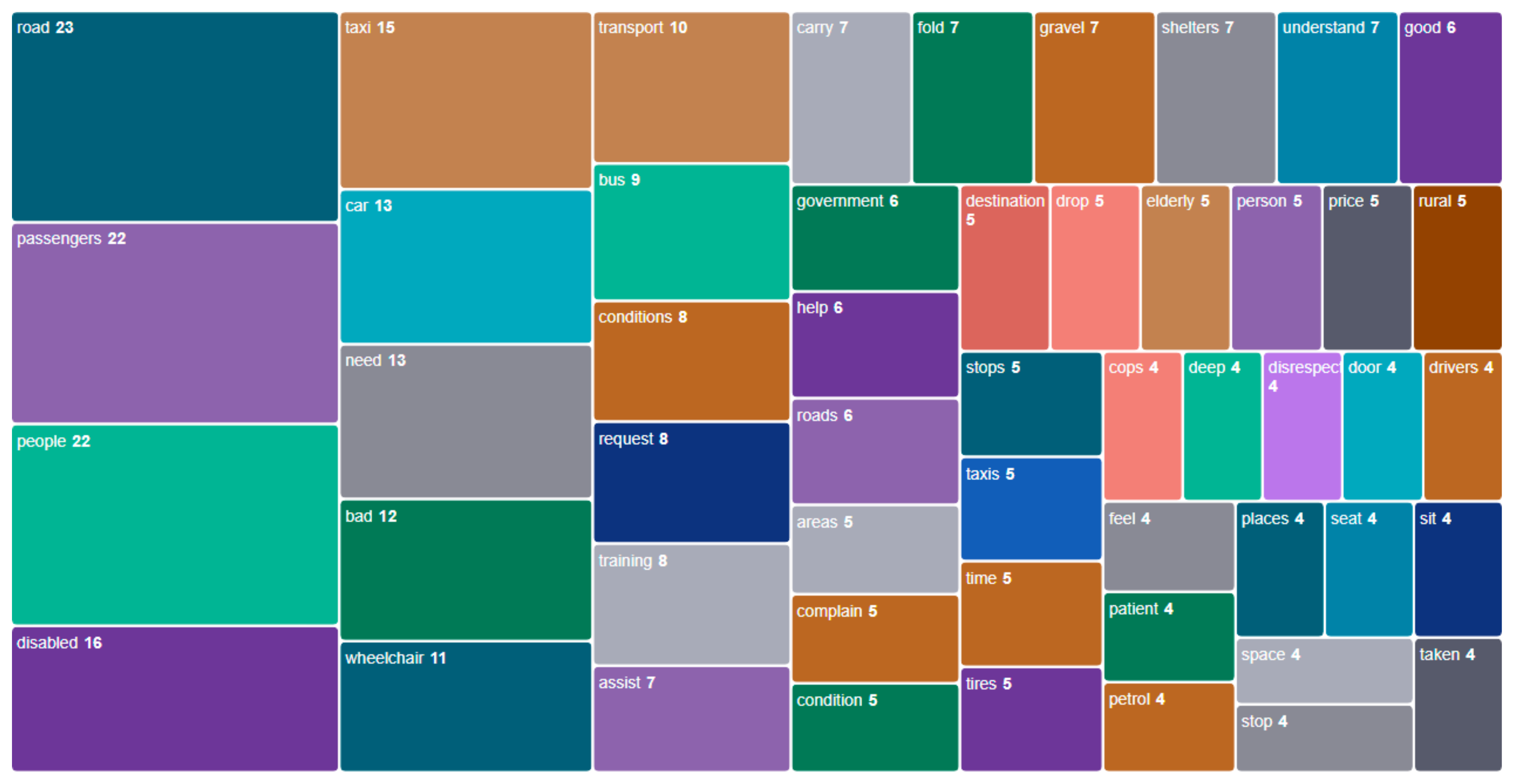

This section presents the key findings from interviews conducted with minibus taxi drivers operating in rural areas of South Africa, focusing on their experiences transporting passengers with disabilities. A treemap shown as

Figure 1 was generated from ATLAS.ti to visualize the distribution and frequency of words across the quotations from the dataset.

Thematic analysis of the interview data initially generated 57 codes across the full dataset. These codes were subsequently reviewed and grouped into conceptually related categories through an iterative process of comparison and refinement. The categories were then synthesized into four overarching themes that capture the key dimensions of drivers’ experiences. Four broad themes emerged from the thematic analysis, which capture the drivers’ viewpoints are (1) Infrastructure and environmental challenges, (2) Accessibility and support for passengers, (3) Operational and economic constraints, and (4) Human interaction and attitudes. Specifically, the theme Infrastructure and environmental challenges comprised 18 codes, Accessibility and support for passengers included 16 codes, Operational and economic constraints consisted of 13 codes, and Human interactions and attitudes were derived from 10 codes. The coding structure reflects both the breadth and depth of issues influencing the transportation of passengers with disabilities in rural contexts. The themes reflect both systemic barriers and individual efforts, highlighting the complexity of providing equitable transport in rural communities. Each theme is illustrated with direct quotations from drivers, identified by number, to preserve the authenticity and diversity of their voices.

Table 2 presents the codes that form the themes of this study.

4.1. Infrastructure and Environmental Challenges

The provision of transport services in rural areas is complex and goes beyond logistical, interpersonal, and physical challenges. Minibus taxi drivers in rural South Africa consistently highlighted the poor state of infrastructure as a major barrier to operating in rural communities. Roads are often gravel, riddled with potholes, and become impassable during the rainy season.

Driver 4 explained, “Sometimes when it rains, the car gets stuck and you are unable to transport passengers,” while Driver 8 added that “the gravel road is in very bad condition and they rarely grade it.”

These conditions not only delay transport but also damage vehicles, requiring frequent repairs to the boot doors and tyres. Drivers are forced to wait for passengers to reach more accessible points, as described by Driver 1: “You have to be patient, reverse the car and collect passengers at central and convenient points.”

Poor transport infrastructure indirectly limits mobility by constraining drivers’ operations, resulting in delays, vehicle breakdowns, and the need for passengers, including people with disabilities, to travel longer distances to reach pick-up points. Vehicle design and space limitations compound these challenges. Drivers expressed frustration with the lack of room to accommodate wheelchairs, often placing them under seats or in the passage.

Driver 6 shared, “Not enough space to put the wheelchair, I put it in under the seats or on the passage.”

The vehicle design of minibus taxis forces drivers to improvise, which can compromise safety and comfort.

Driver 9 emphasized, “No, the taxi is not spacious. Maybe if they were designed in such a way…”

These findings emphasize the urgent need for focused investment in rural transport infrastructure and improvements in vehicle design to promote inclusive mobility. The rainy season presents a particularly severe challenge. Roads become slippery and dangerous, and many areas, especially households located in valleys, are effectively cut off from transport services.

Driver 12 noted, “We wait for them to come up to the main road, because going down in the valley is too risky.” This means that passengers with disabilities living in these areas may be deprived of transport altogether during certain times of the year.

Driver 10 added, “During rainy season we cannot reach some places, so we arrange alternative pickups.” These accounts reveal how environmental conditions intersect with geographic isolation to deepen transport exclusion, particularly for vulnerable populations. The findings emphasize the need for targeted infrastructure improvement and contingency planning to ensure year-round accessibility.

4.2. Accessibility and Support for Passengers

Drivers demonstrated a strong sense of responsibility and compassion when assisting passengers with disabilities. Many described physically helping passengers board and alight from taxis, folding wheelchairs, and ensuring comfortable seating.

Driver 1 stated, “I treat them with respect. I have to open the door, put them in the seat, fold the wheelchair and put it in the passage,” while Driver 15 added, “We help the passengers with disabilities by carrying them in the taxi and by folding the wheelchair.”

These actions reflect a deep commitment to accessibility, even in the absence of formal support or equipment. The code “Assistance with boarding and alighting” was one of the most frequently cited, with drivers detailing the physical and emotional effort involved in ensuring safe transport. Training emerged as a critical gap in service provision. While some drivers had received basic instruction, many expressed a desire for formal training on how to assist passengers with disabilities and the elderly.

Driver 4 noted, “No, but it would be a good idea to be trained on how to handle such cases,” and similarly with Driver 6, “Training would be a good idea as other drivers are not considerate.”

Although drivers are aware of disability needs, the findings revealed that drivers often rely on personal experience and empathy rather than institutional guidance.

Driver 12 reflected, “These trainings grow you in the knowledge of assisting people with disabilities.” These findings highlight the need for structured training programs and policy support to enhance accessibility in rural transport systems.

4.3. Operational and Economic Constraints

Economic pressures significantly shape the experiences of taxi drivers transporting passengers in rural areas. Vehicle maintenance emerged as a significant operational burden for drivers, particularly in rural areas where road conditions accelerate wear and tear. Drivers reported frequent damage to boot doors and tyres due to gravel roads and potholes.

Driver 9 explained, “You constantly have to change the boot doors; tyre damage is common.”

These repairs are costly and often fall on the drivers themselves, with no institutional support or reimbursement. High fuel consumption was another recurring issue, especially when navigating uneven terrain or making multiple trips to inaccessible households.

Driver 8 noted, “The gravel road and long distances mean we use more fuel than usual.”

Combined with rising fuel prices, these factors contribute to the financial strain of providing transport services in rural settings. The cumulative effect of these maintenance and fuel-related costs underscores the need for subsidies or infrastructure improvements to sustain inclusive transport operations.

Many drivers reported that passengers often experience long waits for transport service due to a shortage of available taxis, particularly in remote areas. A minibus taxi also take a long time to fill up because people in rural areas are scattered, resulting in lower densities at any one location.

Driver 6 stated, “There are not enough taxis, so people wait for long hours,” and Driver 3 added, “There is risk of getting stuck; there are some places you cannot go to.”

This scarcity increases demand and stress, particularly at the end of the month when travel spikes. Drivers also mentioned the challenge of balancing passenger needs with luggage management, particularly when transporting passengers who use mobility aids like wheelchairs. Wheelchairs require more storage space, but minibus taxis lack sufficient room for them. At month-end, many passengers from rural areas travel to town to buy groceries, which becomes problematic when there is a wheelchair onboard. Vehicle space and design were also cited as operational constraints. Drivers described how the standard 15-seater taxis are less spacious than 13-seaters, making it difficult to accommodate passengers with disabilities and their equipment.

Driver 1 explained, “Yes, although a 13-seater is more spacious than a 15-seater,” and Driver 4 added, “Groceries/parcels and people cannot mix; the space is not enough.”

Despite these challenges, most drivers do not charge extra for transporting wheelchairs. Driver 6 affirmed, “No, I do not charge,” reflecting a commitment to service over profit. These findings suggest that economic and logistical support is essential to sustain inclusive transport in rural areas.

4.4. Human Interactions and Attitudes

The emotional support associated with providing transport services for passengers with disabilities emerged as a significant matter within the stories shared by drivers. Many described the need for patience and vigilance, especially when passengers required extra time or assistance.

Driver 5 shared, “You have to be patient with them—not rush them. Other passengers usually complain,” while Driver 7 reflected, “Yes, we learn not to rush and to love passengers.”

This constant vigilance, coupled with the unpredictability of rural terrain and passenger needs, contributes to a demanding work environment. Drivers often go beyond their formal duties, remembering destinations for passengers who are unsure, as noted by

Driver 6: “Sometimes people are not completely sure of their destination, I have to remember it and show it to them.”

However, not all interactions are positive. Several drivers reported experiencing rude or disrespectful behavior from passengers, including those with disabilities.

Driver 9 remarked, “These passengers are rude, angry and disrespectful but you need to understand,” and Driver 8 added, “People with disability are normally disrespectful, I think it’s because of past bad experiences with other drivers”.

Despite these challenges, drivers maintain a respectful and empathetic approach, often choosing to remain quiet or avoid confrontation. The code “Passenger complaints” revealed mixed experiences, with some passengers expressing frustration over delays, while others showed understanding and patience. These findings illustrate the complex emotional terrain drivers navigate daily and emphasize the need for psychosocial support and recognition of their caregiving role.

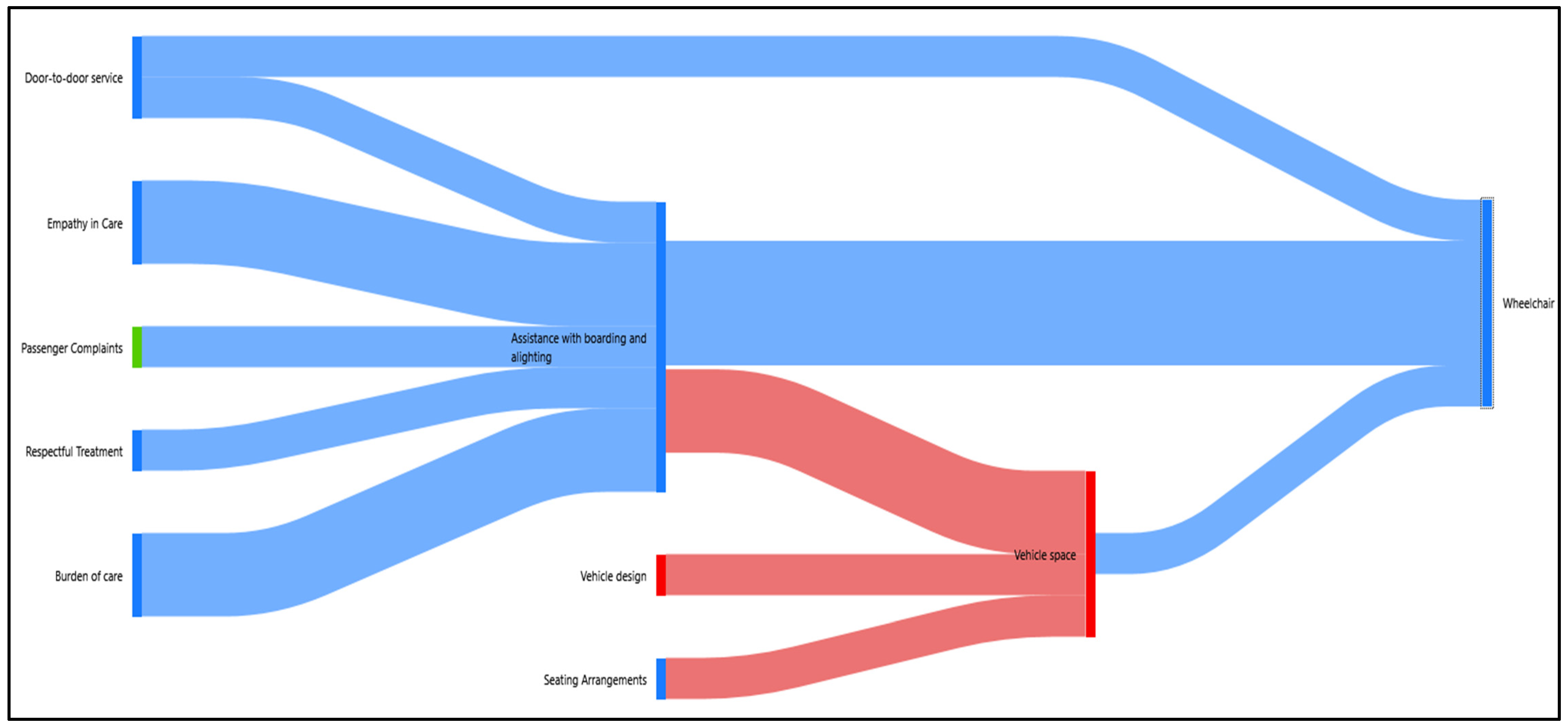

4.5. Thematic Relationships

To visually summarize the thematic relationships and frequency of coded responses, Sankey diagram generated from ATLAS.ti is included (

Figure 2). On the left, interpersonal and service-related elements such as empathy in care, respectful treatment, door-to-door service, passenger complaints, and the burden of care feed into the central practice of assistance with boarding and alighting. This shows that assistance is not a single action, but a relational process shaped by attitudes, expectations, and emotional labour. From the centre, the flow splits toward vehicle-related constraints, particularly vehicle design, seating arrangements, and limited vehicle space. These structural factors mediate how assistance is provided and highlight the operational difficulties drivers face when accommodating wheelchairs. On the right, all flows ultimately connect to wheelchair use, demonstrating that wheelchair transport is the focal point where human interaction, care work, and infrastructural limitations intersect. Overall, the diagram visually reinforces the study’s argument that accessibility is negotiated through everyday practices shaped by both social relations and material constraints, rather than determined by infrastructure alone.

5. Discussion

This section discusses the findings of the study in relation to the objectives: (1) to identify the challenges experienced by minibus taxi drivers in providing transport services to passengers with disabilities in Mt Elias, and (2) to understand drivers’ views on transport infrastructure and services in a rural setting. Drawing on insights from 15 drivers and supported by relevant literature, the discussion explores how structural, operational, and interpersonal factors intersect to shape the accessibility and quality of rural transport for people with disabilities. The discussion of findings is arranged according to the two research objectives, with each theme critically examined in light of the literature.

5.1. The Challenges Experienced by Minibus Taxi Drivers in Providing Transport Services to Passengers with Disabilities in Mt Elias

The study revealed that minibus taxi drivers operating in Mt Elias face various operational challenges common in rural transport, which become even more significant when accommodating passengers with disabilities. These challenges reflect the theme of

Accessibility and support for passengers and are rooted in broader structural and infrastructural constraints within rural transport systems. The substantial physical effort required to assist passengers with boarding and alighting such as lifting passengers, folding wheelchairs, and rearranging seating reflects the absence of accessible vehicle design and supportive infrastructure. In the absence of ramps, lifts, or designated wheelchair spaces, drivers are compelled to compensate through manual labour, effectively transforming transport work into informal caregiving. Drivers play a critical role supporting passengers with disabilities in accessing transport [

56,

57,

58]. Assisting passengers in wheelchairs is a task that is physically demanding and time-consuming. This aligns with findings by Duri and Luke [

13], who emphasized that drivers in Tshwane often act as informal caregivers, performing tasks beyond their job descriptions due to the absence of accessible infrastructure and policy support.

Beyond physical strain, drivers also navigate emotional and interpersonal challenges. These experiences correspond with the theme of

Human interactions and attitudes. Feelings of stress, vigilance, and occasional tension during interactions with passengers can be understood in relation to demanding working conditions, time pressures, and economic imperatives within the informal minibus taxi industry. Similar patterns have been reported in studies from Sweden, where drivers’ exposure to stressful environments increases the likelihood of conflict and emotional fatigue [

58]. Some reported that passengers with disabilities are sometimes perceived as demanding or disrespectful. In this study, only a few drivers mentioned that fellow passengers complain about delays caused by assisting passengers with disabilities. Most of the drivers highlighted the awareness and consideration shown by fellow passengers regarding the needs of passengers with disabilities. The generally supportive behaviour of co-passengers reported by most drivers further indicates that social awareness can mitigate interpersonal strain, a finding consistent with studies showing mixed but context-dependent public attitudes toward disability [

59,

60]. Despite these challenges, many drivers demonstrated empathy and patience, reinforcing the importance of the role of drivers in transporting passengers with disabilities [

57]. The importance of awareness of passengers needs was highlighted as crucial for providing appropriate assistance and ensuring a positive travel experiences [

58].

The absence of formal training emerged as another significant challenge and is closely linked to the theme of

Accessibility and support for passengers, particularly the subtheme related to training and awareness. Without structured guidance, drivers rely on personal experience, intuition, and informal norms to assist passengers with disabilities. While this can enhance compassionate responses, it also leads to inconsistent practices and places the burden of responsibility on individual drivers rather than on the transport system. Previous research similarly shows that a lack of disability-specific training limits drivers’ confidence and awareness of diverse mobility needs [

37,

61]. However, drivers expressed a desire for structured education on how to assist passengers with disabilities, recognizing that their current practices are based on personal experience rather than professional guidance. Without such training, drivers are left to improvise, which can compromise both safety and dignity for passengers. When drivers are informed and empathetic, it creates a more welcoming environment for all passengers [

58].

5.2. Understand Drivers’ Views on Transport Infrastructure and Services in Mt Elias

Drivers’ views on transport infrastructure in Mt Elias were predominantly negative and closely reflect the theme of

Infrastructure and environmental challenges identified in the Results. Poor road conditions, particularly on gravel roads and with potholes, were the most common barriers to service delivery. These conditions can be understood as the outcome of long-standing structural neglect of rural infrastructure, where investment priorities often favour urban and economically productive corridors over sparsely populated rural areas [

9,

22]. As a result, drivers operate in environments where infrastructure fails to support reliable and inclusive mobility. During the rainy season, roads become slippery and impassable, particularly in valley areas where households are effectively cut off. Porter et al.’s [

10] research highlights that long walks to transport pick up points can be challenging for older individuals and people with disabilities, especially in rural areas with difficult terrain and during rainy conditions. In Mt Elias, transport restrictions are more severe for people with disabilities and other groups with reduced mobility. These findings are consistent with Fobosi and Malima [

24], who argue that rural infrastructure development in South Africa often overlooks the needs of marginalized communities, reinforcing spatial inequality and social exclusion.

The lack of routine maintenance of gravel roads emerged as a particularly severe concern within

the Infrastructure and environmental challenges theme. The roads are not regularly graded or repaired, leading to deep potholes, uneven surfaces, and erosion. During the rainy season, the situation worsens significantly and roads become slippery and impassable, especially in valley areas, effectively cutting off households from transport access. Drivers reported that vehicles often get stuck or damaged, and they are forced to wait for passengers to walk to more accessible points. This aligns with previous studies that argue that rural infrastructure development in South Africa is marked by inequality and neglect, particularly in historically marginalized regions [

9,

22,

24]. Poor road conditions in rural areas not only hinder mobility but also deepen social exclusion, especially for people with disabilities. The lack of consistent road maintenance in Mt Elias reflects broader structural barriers that undermine the feasibility of inclusive transport services in rural South Africa.

Vehicle-related challenges further illustrate how infrastructure constraints intersect with operational realities. These issues align with the theme of

Operational and economic constraints, where drivers reported frequent damage to boot doors and tyres, increased fuel consumption due to rough terrain, and insufficient vehicle space to accommodate wheelchairs. Such constraints limit drivers’ capacity to provide safe and efficient services and place additional financial burdens on them. Because minibus taxis operate without operating subsidies, the financial costs associated with repairs and fuel are borne largely by drivers or owners, increasing economic pressure and limiting flexibility in service provision. These findings support arguments by Pretorius et al. [

62] that mixed fleet scheduling and vehicle redesign are necessary to improve the feasibility of inclusive transport. Together, these dynamics illustrate that drivers’ views on infrastructure are shaped not only by road quality but by the cumulative effects of governance gaps, economic constraints, and vehicle environment mismatches that undermine inclusive rural transport services.

5.3. Implications and Recommendations

Current frameworks tend to focus on urban mobility and formal public transport systems. Rural transport is often overlooked and yet informal paratransit services dominate rural areas. Integrating minibus taxis into rural accessibility strategies through partnerships with taxi associations and regulatory authorities could bridge this policy gap. Targeted funding and subsidy mechanisms are also necessary to offset the additional costs drivers face when operating in difficult terrains or accommodating passengers with mobility aids.

The government is recommended to establish mandatory disability awareness and passenger assistance programs for rural taxi drivers, focusing on safe lifting techniques, respectful communication, and basic customer care. Taxi associations could play an important role in training of drivers. Infrastructure improvement that prioritize the maintenance and grading of rural gravel roads, especially those serving communities with high numbers of people with disabilities could help in the short run. Improved road conditions would enhance both safety and reliability. Community awareness campaigns designed to educate the public on the importance of respect and patience for passengers with disabilities during travel are crucial. Such initiatives play a significant role in promoting an inclusive environment that encourages understanding and support for all community members.

Beyond practical recommendations, this study contributes to disability studies by reinforcing relational and social models of disability, demonstrating how transport exclusion is produced through everyday interactions between people with disabilities, service providers, and infrastructural constraints. The findings advance research on rural and inclusive transport by highlighting the role of informal transport actors in shaping accessibility outcomes. These insights also inform policy debates by highlighting the need for equity-oriented mobility frameworks that recognize informal systems as integral to inclusive transport planning.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. Methodologically, it is based on a qualitative design with a small, purposively selected sample of minibus taxi drivers operating on a single rural route; therefore, the findings are not statistically generalizable. The analysis relies on drivers’ accounts and does not include the perspectives of passengers with disabilities or other stakeholders. Contextually, the study is situated within one rural area in KwaZulu-Natal and focuses on informal minibus taxi transport, which may limit transferability to other regions or transport systems. In addition, drivers’ narratives primarily reflected experiences with passengers with reduced mobility, particularly wheelchair users.

Future research could extend this work by incorporating the perspectives of passengers with diverse types of disabilities, examining multiple rural and peri-urban contexts, and comparing formal and informal transport systems. Such studies would strengthen theoretical and empirical understandings of inclusive mobility and transport exclusion.

6. Conclusions

This study explored the experiences of minibus taxi drivers in transporting people with disabilities in rural areas of South Africa, focusing on Mt Elias. The findings highlight that the accessibility challenges facing passengers with disabilities are deeply intertwined with broader structural and systemic barriers affecting rural transport. Poor road conditions, inadequate vehicle design, and the absence of transport infrastructure make it difficult for drivers to provide safe and efficient services. Despite these obstacles, drivers often demonstrate compassion and a strong sense of responsibility, going beyond their formal roles to assist passengers with boarding and alighting.

The study also revealed that drivers receive little institutional or policy support. Most have not received any formal training in disability awareness or passenger assistance, relying instead on personal experience and empathy. This gap highlights the need for targeted interventions such as structured disability sensitivity training and incentives for inclusive practices within the paratransit industry. Furthermore, the poor state of rural infrastructure, especially gravel roads that become impassable during the rainy season, continues to restrict both mobility and economic opportunities for marginalized populations, reinforcing spatial inequality. Future research could build on these findings by further developing theoretical frameworks that conceptualize transport exclusion as a relational and practice-based process, shaped through everyday interactions between users, service providers, and infrastructural conditions.

In conclusion, improving transport services for people with disabilities in rural South Africa demands a comprehensive, multi-layered approach that integrates policy reform, infrastructural investment, and human capacity development. Collaborative initiatives between government agencies, transport associations, and disability advocacy groups can foster an environment where inclusivity, accessibility, and dignity are central to rural mobility systems. Ultimately, equitable access to transport is not only a technical or logistical issue but a matter of social justice and human rights.