Artistic Experience of the Visually Impaired: A Qualitative Study on the Process of Creating Clay Media Artworks for Low Vision in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do individuals with low vision in Indonesia experience the process of creating artworks using clay media?

- (2)

- What perceptions do low vision individuals hold about clay as an artistic medium?

- (3)

- How do they engage in and navigate the process of creating clay artworks?

- (4)

- What meanings, values, and skills emerge from their artistic experiences with clay media?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Research Methods

2.3. Participants

2.4. Research Instrument

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

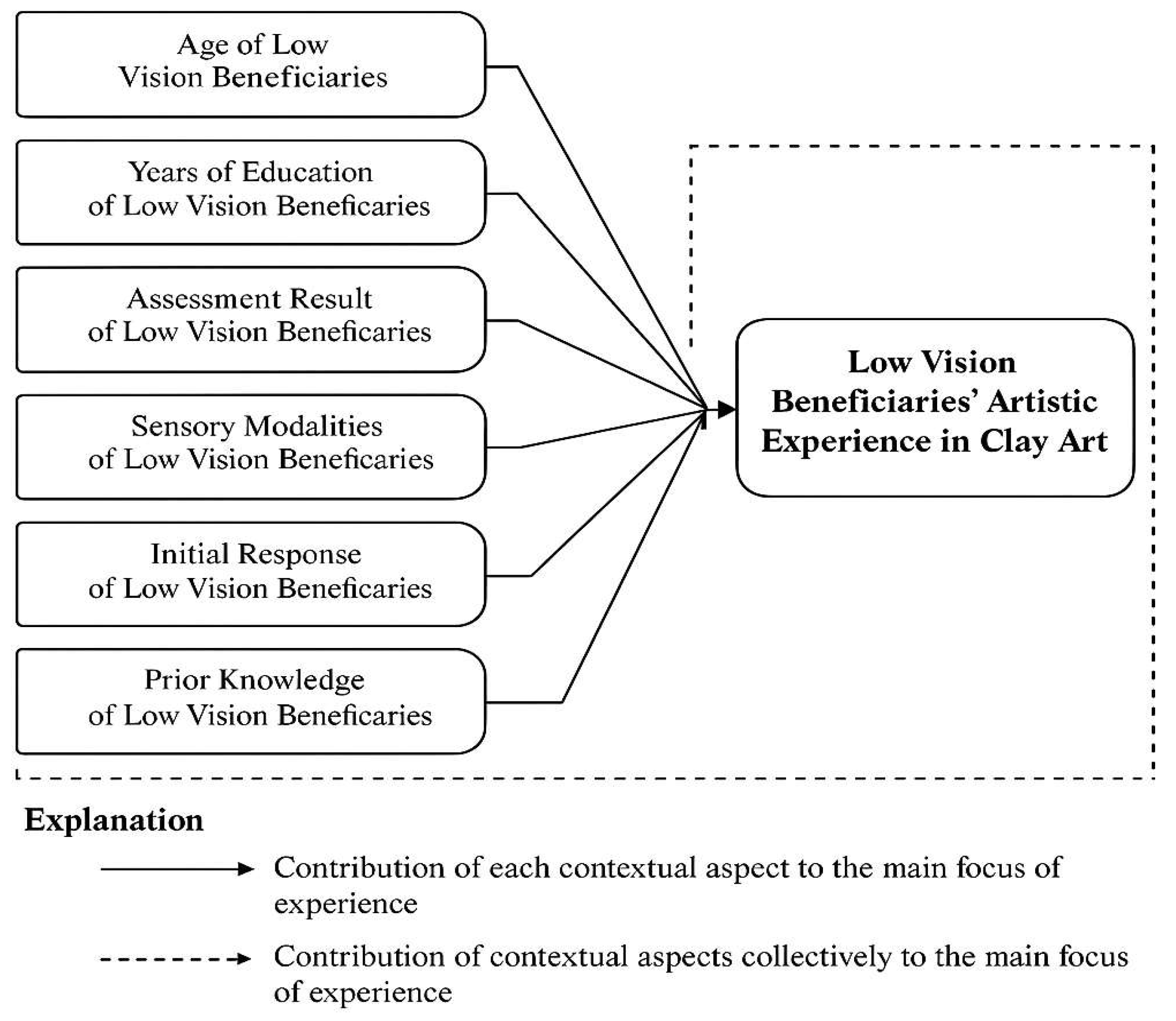

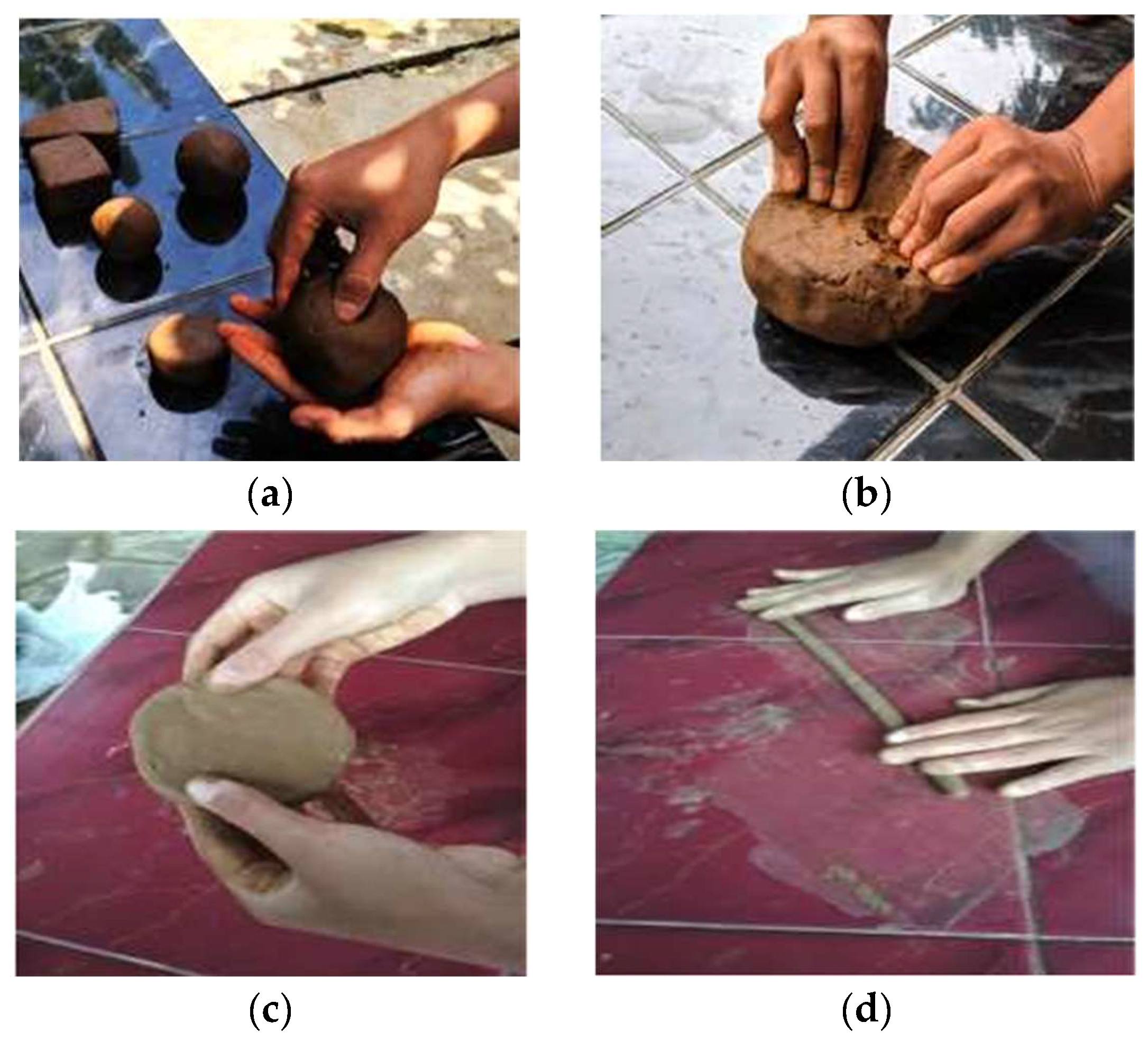

3.1. Techniques and Creative Processes of Low Vision Beneficiaries Towards Clay Materials

“I got to know clay materials during school learning, and together with friends were introduced through hand touch to identify the clay. I also played with friends at home when making a well at home, and I wanted to try making bowls, plates, and other eating utensils, which I hope can become objects that can be used for everyday needs”.

“When I was taking lessons at SDLB-A, the teacher asked me to hold clay by feeling and squeezing it. The teacher asked me to form various shapes from my fists to produce shapes like small balls, plates, and asked me to combine the shapes. What I remember at that time was making fruit shapes and people shapes. Back then, my friends at SDLB-A were very happy and enthusiastic about the lesson. It is possible that if there are more activities like that, I will feel challenged to create works of art using clay that suit my wishes, namely wanting to make animal statues”.

“I used to do various art activities when I had normal vision. When I was a child, until I was an adult, I could understand how to create art, especially using clay, from kindergarten to high school. I have various experiences in creating art with clay media, such as making statues, pottery, and playing with clay. I often got that knowledge from junior high and high school in the Arts and Crafts (SBK) subject. In the past, during SBK learning, my teacher assigned me to make a face sculpture artwork and also told me to make pottery with the motif.”

3.2. The Skill Development and Motor Improvement of Low Vision Beneficiary Artistic Experience in Creating Art with Clay Media

3.3. The Perseverance, Discipline, and Focus of Artistic Experience for Low Vision Beneficiaries

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disability Language/Terminology Positionality Statement

Appendix A

| Date & Location: Participant Code: Duration: | |||

| Section | Focus Area | Interview Questions | Purpose/Rationale |

| A. Background Information | Personal and Educational Background |

| To understand participant context |

| B. Early Artistic Experience with Clay | First Encounter with Clay Media |

| To explore the participant’s initial sensory and emotional experiences in using clay |

| C. Learning Process in Formal Education | School-Based Art Activities |

| To identify instructional approaches that support artistic learning for low-vision students |

| D. Motivation and Emotional Engagement | Personal Meaning and Enjoyment |

| To uncover emotional connections and motivation behind participation in clay art |

| E. Creative Process and Techniques | Tactile Exploration and Creation |

| To understand the sensory-driven creative process and decision-making in art-making |

| F. Challenges and Adaptation | Difficulties and Problem-Solving |

| To explore adaptive strategies in dealing with visual limitations during art creation |

| G. Reflection and Artistic Meaning | Personal Interpretation and Value |

| To capture reflective meaning and personal growth from artistic experiences |

Appendix B

| No | Component of Ability (Visual Limitation) | Indicators and Scoring Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Measuring the distance between eyes and the object being held | 5 = Distance ≤ 10 cm |

| 4 = Distance ≈ 15 cm | ||

| 3 = Distance ≈ 20 cm | ||

| 2 = Distance ≥ 25 cm | ||

| 1 = Distance ≥ 25 cm | ||

| 2 | Observation of object size through tactile comparison | 5 = Understands observed object immediately |

| 4 = Observes gradually | ||

| 3 = Observes randomly | ||

| 2 = Observes without concentration | ||

| 1 = Does not observe clearly | ||

| 3 | Focus on moving objects | 5 = Accurately identifies predetermined moving object |

| 4 = Focuses on object from left/right direction | ||

| 3 = Randomly captures object | ||

| 2 = Object capture not yet targeted | ||

| 1 = No object capture observed | ||

| 4 | Sensitivity to color quality | 5 = Explains color quality accurately according to distance and type |

| 4 = Explains color quality correctly based on observation distance | ||

| 3 = Explains based on light intensity | ||

| 2 = Explains color quality randomly | ||

| 1 = Unable to explain color quality | ||

| 5 | Reaction to light stimulus | 5 = Adapts sensitivity to light |

| 4 = Avoids excessive light sensitivity | ||

| 3 = Seeks optimal light sensitivity | ||

| 2 = Gradually adjusts to light sensitivity | ||

| 1 = Not sensitive to light stimulus | ||

| 6 | Observation of object form quality | 5 = Uses both eyes simultaneously |

| 4 = Uses either left or right eye | ||

| 3 = Uses right eye only | ||

| 2 = Moves head to focus | ||

| 1 = Shows no response | ||

| 7 | Attitude during observation with visual limitation | 5 = Relaxed and focused during observation |

| 4 = Tense during observation | ||

| 3 = Indifferent or inattentive | ||

| 2 = Uncooperative during observation | ||

| 1 = Does not follow visual observation instructions |

| No | Component of Ability (Non-Visual Sensitivity) | Indicators and Scoring Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Auditory sensitivity | 1 = No response |

| 2 = Recognizes sound (Recognition) | ||

| 3 = Differentiates sound (Differensis) | ||

| 4 = Identifies similarity of sounds (Similarities) | ||

| 5 = Confirms sound (Verification) | ||

| 2 | Tactile sensitivity | 1 = No perception |

| 2 = Recognizes object (Recognition) | ||

| 3 = Differentiates objects (Differensis) | ||

| 4 = Associates objects (Interrelated) | ||

| 5 = Confirms object (Verification) | ||

| 3 | Olfactory sensitivity | 1 = No sense detected |

| 2 = Recognizes smell (Recognition) | ||

| 3 = Differentiates smell (Differensis) | ||

| 4 = Confirms smell (Verification) | ||

| 5 = Perceives smell (Perception) | ||

| 4 | Taste sensitivity | 1 = No perception |

| 2 = Recognizes taste (Recognition) | ||

| 3 = Differentiates taste (Differensis) | ||

| 4 = Confirms taste (Verification) | ||

| 5 = Perceives taste (Perception) |

Appendix C

| Document Type | Key Focus/Variable | Analytical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Clay Artworks | Texture, form, symmetry, emotional representation | Smooth textures suggest calmness; asymmetry may reflect creative exploration. |

| Participant Reflections | Language of sensory and emotional engagement | Describes clay as “alive” and “responsive to touch.” |

| Facilitator Notes | Observed creative processes, adaptive behaviors | Notes gradual improvement in tactile sensitivity and confidence. |

| Audio Recordings | Tone, pace, and emotion in participant voice | Increased enthusiasm during later sessions. |

| Photographs (with consent) | Stages of artwork development | Visual evidence of progression and experimentation. |

References

- Papa, M.; Papa, A. The transformative capacity of communication for social change and peacebuilding. In The Routledge Handbook of Conflict and Peace Communication, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.A. Art as a Mirror of Cultural Values: A Philosophical Exploration of Aesthetic Expressions. Cult. Int. J. Philos. Cult. Axiolog. 2025, 22, 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Fajrie, N.; Purbasari, I.; Bamiro, N.B.; Evans, D.G. Does art education matter in inclusiveness for learners with disabilities? A systematic review. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 23, 96–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.M.; Smart, E.; King, G.; Curran, C.J.; Kingsnorth, S. Performance and visual arts-based programs for children with disabilities: A scoping review focusing on psychosocial outcomes. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Evie, F.; Kleege, G. The gravity, the levity: Let us speak of tactile encounters. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2018, 38, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, P. Towards a Holistic Paradigm of Art Education Art Education: Mind, Body, Spirit; Visual Arts Research; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2006; pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Golomb, C. Representational conceptions in two-and three-dimensional media: A developmental perspective. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2007, 1, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessey, B.A. Taking a systems view of creativity: On the right path toward understanding. J. Creat. Behav. 2017, 51, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, E.; Goldstein, T.R.; Vincent-Lancrin, S. Art for art’s sake. The impact of arts education. Educ. Res. Innov. 2013, 24, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, E.W. What Can Education Learn from the Arts About the Practice of Education? J. Curric. Superv. 2002, 18, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi, C.A. (Ed.) Art Therapy and Health Care; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, C.H. A history of materials and media in art therapy. In Materials and Media in Art Therapy: Critical Understandings of Diverse Artistic Vocabularies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 3–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sholt, M.; Gavron, T. Therapeutic qualities of clay-work in art therapy and psychotherapy: A review. Art Therapy 2006, 23, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phutane, M.; Wright, J.; Castro, B.V.; Shi, L.; Stern, S.R.; Lawson, H.M.; Azenkot, S. Tactile materials in practice: Understanding the experiences of teachers of the visually impaired. ACM Trans. Access. Comp. (TACCESS) 2022, 15, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, A. What My Students Taught Me about Disability. Threshold. Educ. 2023, 46, 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, J.K.; Hinz, L.D.; Lusebrink, V.B. Clay art therapy on emotion regulation: Research, theoretical underpinnings, and treatment mechanisms. In The Neuroscience of Depression; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, P. The Beauty of Clay: Exploring contemporary Ceramic Art as an Aesthetic Medium in Education. Comun. Rev. Científica Comun. Educ. 2024, 32, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.; Yeager, J.L. The implementation of inclusive education for students with special needs in Indonesia. Excell. High. Educ. 2011, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rante, S.V.N.; Wijaya, H.; Tulak, H. Far from expectation: A systematic literature review of inclusive education in Indonesia. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 6340–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höger, B.; Meier, S. Exploring Marginalized Perspectives: Participatory Research in Physical Education with Students with Blindness and Visual Impairment. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2025, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, R.; Zavšek, K.; Vidrih, A. Visual Art Activities as a Means of Realizing Aspects of Empowerment for Blind and Visually Impaired Young People. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2025, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, D.B.; van Schalkwyk, I. Creative arts interventions to enhance adolescent well-being in low-income communities: An integrative literature review. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 34, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.E.; Bergelson, E. Making sense of sensory language: Acquisition of sensory knowledge by individuals with congenital sensory impairments. Neuropsychologia 2022, 174, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Massaro, M.; Dumay, J.; Bagnoli, C. Transparency and the rhetorical use of citations to Robert Yin in case study research. Med. Accoun. Res. 2019, 27, 44–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, B.P.; Silverstein, S.M.; Papathomas, T.V.; Krekelberg, B. Correcting visual acuity beyond 20/20 improves contour element detection and integration: A cautionary tale for studies of special populations. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2016; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. Writing in the Dark: Phenomenological Studies in Interpretive Inquiry; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Larkin, M.; Flowers, P. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2021; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, C.D.S.F. Healing and edible clays: A review of basic concepts, benefits and risks. Environ. Geochem. Health 2018, 40, 1739–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoe, M.R.; Liechty, T. Meanings of participation in a leisure arts pottery programme. World Leis. J. 2017, 59, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, O.E.; Gurayah, T. Therapeutic implications of clay palm press ceramic art practice. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2025, 12, 2442833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, D.; Davids, K.; Wheat, J.; Seifert, L.; Liukkonen, J.; Jaakkola, T.; Kerr, G. The role of textured material in supporting perceptual-motor functions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, E.; Brook, I.; Prior, J. Between Nature and Culture: The Aesthetics of Modified Environments; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, T. A meeting with clay: Individual narratives, self-reflection, and action. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2017, 1, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.; Vermol, V.V.; Anwar, R.; Kaspin, S. Visual Art Accessibility and Art Experience for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Int. J. Des. Soc. 2024, 19, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.D. A study of multi-sensory experience and color recognition in visual arts appreciation of people with visual impairment. Electronics 2021, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobnick, J.; Fisher, J. Introduction: Sensory aesthetics. Senses Soc. 2012, 7, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagtvedt, H. A brand (new) experience: Art, aesthetics, and sensory effects. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, G.M. Neurocognitive rehabilitation: Skills or strategies? Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 72, 7206150010p1–7206150010p16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, N.K.; Gjærum, R. The Aesthetic Model of Disability. In Theatre and Democracy: Building Democracy in Post-War and Post-Democratic Contexts; Janse Van Vuuren, P., Rasmussen, B., Khala, A., Eds.; Cappelen Damm Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2021; pp. 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, G. Art therapy and flow: A review of the literature and applications. Art Therapy 2013, 30, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, E.R. Liberation psychology, creativity, and arts-based activism and artivism: Culturally meaningful methods connecting personal development and social change. In Liberation Psychology: Theory, Method, Practice, and Social Justice; Comas-Díaz, L., Torres Rivera, E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajrie, N.; Purbasari, I.; Bamiro, N. The perceptual ability of visual impaired children in the experience of making clay media artworks. Arts Educ. 2024, 40, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, C.D.; Brown-Iannuzzi, J.L.; Payne, B.K. Sequential priming measures of implicit social cognition: A meta-analysis of associations with behavior and explicit attitudes. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, E.Y. Temporal differences in eye–hand coordination between children and adults during manual action on objects. Hong Kong J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 31, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A. Art and Education: Fostering Creativity and Critical Thinking in Humanity. J. Relig. Soc. 2023, 1, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdass, D.; Zimmerman, B.J. Developing self-regulation skills: The important role of homework. J. Adv. Acad. 2011, 22, 194–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt-Gross, C. From Objects to Relationships: Reviving Connectivity through Collaborative Artmaking. J. Soc. Theory Art Educ. 2025, 44, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonke, J.; Pesata, V.; Colverson, A.; Morgan-Daniel, J.; Rodriguez, A.K.; Carroll, G.D.; Karim, H. Relationships between arts participation, social cohesion, and well-being: An integrative review of evidence. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1589693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondent ID | Age | Gender | Level of Vision | Onset of Impairment | Prior Artistic Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R01 | 22 | Female | Can perceive light and shadow only | Congenital | None |

| R02 | 35 | Male | Can distinguish large shapes and colors | Acquired (at age 18) | Some (school crafts) |

| R03 | 31 | Female | Total blindness | Congenital | Some (music) |

| R04 | 19 | Male | Can perceive light and motion | Congenital | None |

| R05 | 32 | Female | Total blindness | Acquired (at age 25) | None |

| R06 | 28 | Female | Can distinguish large shapes | Congenital | Extensive (hobbyist weaver) |

| R07 | 31 | Male | Can perceive strong colors | Acquired (at age 12) | None |

| R08 | 38 | Female | Total blindness | Congenital | Some (school crafts) |

| R09 | 25 | Male | Can perceive light and shadow only | Congenital | None |

| R10 | 39 | Female | Total blindness | Acquired (at age 30) | None |

| R11 | 21 | Male | Can distinguish large shapes and colors | Congenital | Some (drawing) |

| R12 | 25 | Male | Can perceive motion and large shapes | Acquired (at age 5) | Extensive (wood carving) |

| R13 | 33 | Male | Total blindness | Congenital | None |

| R14 | 29 | Female | Can perceive light and shadow only | Acquired (at age 22) | None |

| R15 | 33 | Female | Total blindness | Congenital | Some (music) |

| No. | Documentation of Artworks | Identity of Artwork | Analysis of the Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Title of Work “Frog”

| The shape of the object produced using a pinch massage technique by forming an animal in a symmetrical position. The addition of objects is used to produce components of the shape on each side of the object |

| 2 |  | Title of Work: “Ashtray of Love”

| Applying subtractive techniques to form depressions in clay materials in an effort to produce a central indentation in the artwork |

| 3 |  | Title of Work: “Kura-Kura”

| The creation of the work was carried out using the addition of clay materials with a plate technique and elements of cross or zig-zag lines as texture accents on the artwork |

| 4 |  | Title of Work “Small Jug”

| Forming clay material using a wooden rod construction inside using a twisting technique |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fajrie, N.; Purbasari, I.; Khoeron, S.; Purnama, I.Y.; Pratama, H. Artistic Experience of the Visually Impaired: A Qualitative Study on the Process of Creating Clay Media Artworks for Low Vision in Indonesia. Disabilities 2025, 5, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040098

Fajrie N, Purbasari I, Khoeron S, Purnama IY, Pratama H. Artistic Experience of the Visually Impaired: A Qualitative Study on the Process of Creating Clay Media Artworks for Low Vision in Indonesia. Disabilities. 2025; 5(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleFajrie, Nur, Imaniar Purbasari, Slamet Khoeron, Ika Yuni Purnama, and Hendri Pratama. 2025. "Artistic Experience of the Visually Impaired: A Qualitative Study on the Process of Creating Clay Media Artworks for Low Vision in Indonesia" Disabilities 5, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040098

APA StyleFajrie, N., Purbasari, I., Khoeron, S., Purnama, I. Y., & Pratama, H. (2025). Artistic Experience of the Visually Impaired: A Qualitative Study on the Process of Creating Clay Media Artworks for Low Vision in Indonesia. Disabilities, 5(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5040098