Linking System of Care Services to Flourishing in School-Aged Children with Autism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Data Collection Process

2.2. Study Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variables

2.2.2. Independent Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

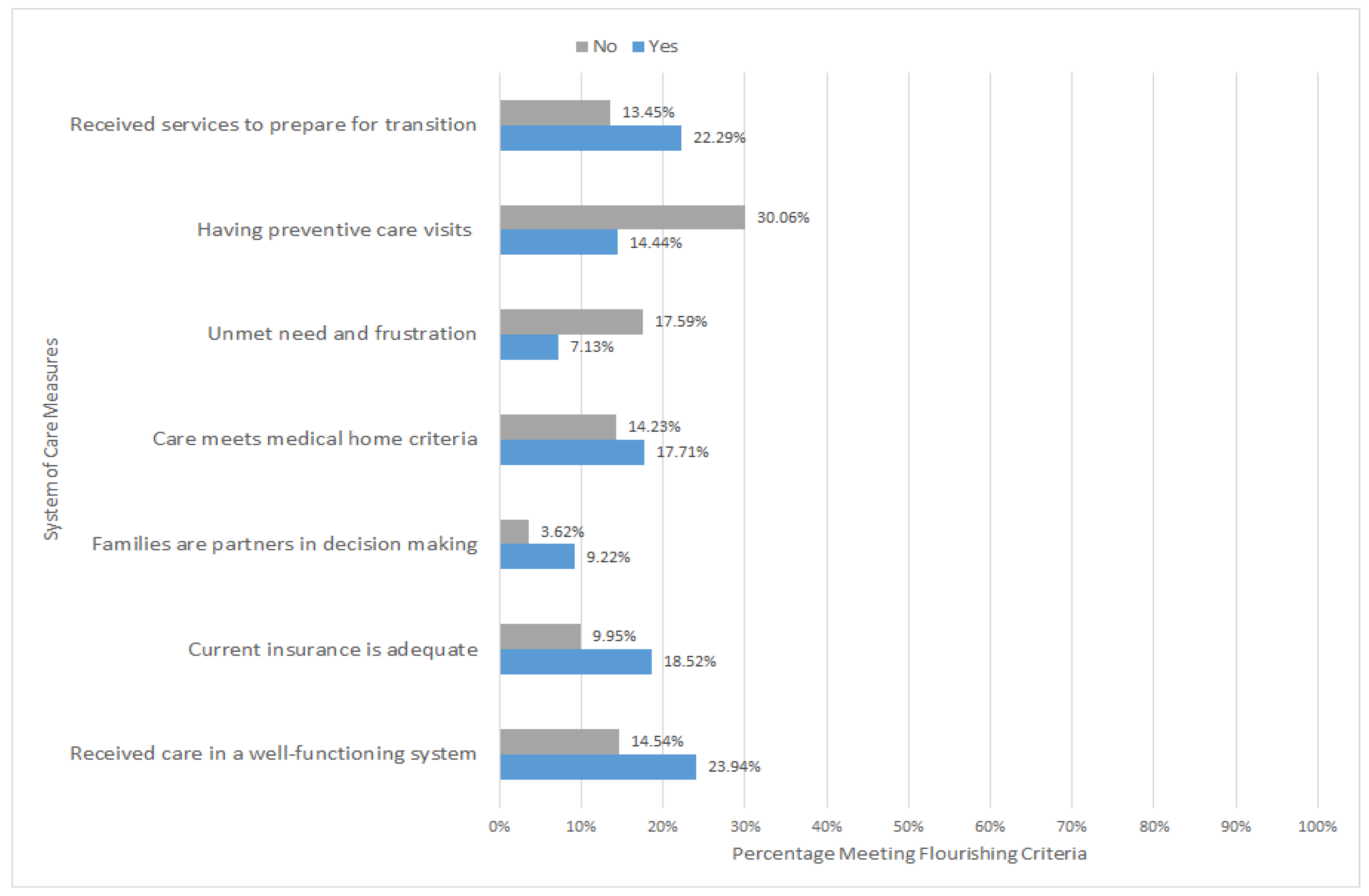

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keyes, C.L. Complete mental health: An agenda for the 21st century. In Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived; Keyes, C.L., Haidt, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lippman, L.H.; Moore, K.A.; Guzman, L.; Ryberg, R.; McIntosh, H.; Ramos, M.F.; Caal, S.; Carle, A.; Kuhfeld, M. Flourishing Children: Defining and Testing Indicators of Positive Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.L. Integrating positive psychology into health-related quality of life research. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agenor, C.; Conner, N.; Aroian, K. Flourishing: An evolutionary concept analysis. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 38, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, J.F.; Shaw, J.S.; Duncan, P.M. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 4th ed.; American Academy of Pediatrics: Elk Grove Village, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, C.L.; Morrison, M.; Perkins, S.K.; Brosco, J.P.; Schor, E.L. Quality of life and well-being for children and youth with special health care needs and their families: A vision for the future. Pediatrics 2022, 149 (Suppl. S7), e2021056150G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, C.L.; Ratcliff, K.; Collins, D.M.; Flanagan, J.; Hong, I. Flourishing in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, C.; Pei, Y.; Cao, F. Association of positive childhood experiences with flourishing among children with ADHD: A population-based study in the United States. Prev. Med. 2024, 179, 107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, M.C.; Snider, L.; Prelock, P.A.; Wood-Dauphinee, S.; Kehayia, E. Health-related quality of life in children with high-functioning autism. Autism 2015, 19, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, E.; Hinckson, E.; Krageloh, C. Assessment of quality of life in children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: A critical review. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1069–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, K.; Boyd, B.A.; Hamm, J.V.; Kucharczyk, S. Supporting independence in adolescents on the autism spectrum. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2014, 35, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSCH Data Brief. Available online: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/data-research/nsch-data-brief-2019-mental-bh.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs (CYSHCN). Available online: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs-impact/focus-areas/children-youth-special-health-care-needs-cyshcn (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Benevides, T.W.; Carretta, H.J.; Lane, S.J. Unmet Need for Therapy Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results from the 2005–2006 and 2009–2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpur, A.; Lello, A.; Frazier, T.; Dixon, P.J.; Shih, A.J. Health Disparities among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Analysis of the National Survey of Children’s Health 2016. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1652–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.A.; Gehricke, J.G.; Iadarola, S.; Wolfe, A.; Kuhlthau, K.A. Disparities in Service Use Among Children with Autism: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2020, 145, S35–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallman, A.R.; Artis, J.; Watson, L.; Wright, S. Systematic Review of Disparities and Differences in the Access and Use of Allied Health Services Amongst Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51 (Suppl. S7), 1316–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, G.; Burner, K. Behavioral interventions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A review of recent findings. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2011, 23, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, L.M.; Schwefel, L.L. Flourishing and Functional Difficulties among Autistic Youth: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. Inclusive Education for Autistic Children: Helping Children and Young People to Learn and Flourish in the Classroom; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande, K.; Ingersoll, B.R. Improving Service Access in ASD: A Systematic Review of Family Empowerment Interventions for Children with Special Healthcare Needs. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 8, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicano, E.; Heyworth, M. The Foundations of Autistic Flourishing. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 2021–2022 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) Combined Dataset: Fast Facts. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/docs/default-source/nsch-docs/2021-2022-nsch-fast-facts_cahmi.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- National Survey of Children’s Health Data (NSCH). U.S. Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/NSCH (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI). 2021–2022 National Survey of Children’s Health (2 Years Combined), SAS Dataset. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health Supported by Cooperative Agreement U59MC27866 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/help/dataset/2021-2022-combined-nsch-dataset-codebook-instruction (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Bethell, C.D.; Gombojav, N.; Whitaker, R.C. Family resilience and connection promote flourishing among US children, even amid adversity. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI). NSCH Guide to Topics and Questions. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/topics_questions/2022-nsch-guide-to-topics-and-questions (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Moore, K.A.; Lippman, L.H. What Do Children Need to Flourish? Conceptualizing and Measuring Indicators of Positive Development; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, T.Y.; Hayes, D.K. Adverse family experiences and flourishing amongst children ages 6–17 years: 2011/12 National Survey of Children’s Health. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 70, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donney, J.F.; Ghandour, R.M.; Kogan, M.D.; Lewin, A. Family-Centered Care and Flourishing in Early Childhood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 63, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellando, J.; Fussell, J.J.; Lopez, M. Autism Speaks Toolkits: Resources for Busy Physicians. Clin. Pediatr. 2016, 55, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASD Services Toolkits and Resources. Available online: https://autismsciencefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Autism-Toolkits.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Autism Speaks. Autism Speakes Tool Kits. Available online: https://www.autismspeaks.org/autism-speaks-tool-kits (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- National Health Service. A National Framework to Deliver Improved Outcomes in All-Age Autism Assessment Pathways: Guidance for Integrated Care Boards. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/a-national-framework-to-deliver-improved-outcomes-in-all-age-autism-assessment-pathways-guidance-for-integrated-care-boards/ (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Negin, F.; Ozyer, B.; Agahian, S.; Kacdioglu, S.; Ozyer, G.T. Vision-assisted recognition of stereotype behaviors for early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Neurocomputing 2021, 446, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Ahmedt-Aristizabal, D.; Gammulle, H.; Denman, S.; Armin, M.A. Vision-based activity recognition in children with autism-related behaviors. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahaad Almufareh, M.; Tehsin, S.; Humayun, M.; Kausar, S. Facial Classification for Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 3, 20240025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.; Lim, J.H.; Hong, J.; Hong, S.B.; Park, Y.R. Development and Validation of a Joint Attention-Based Deep Learning System for Detection and Symptom Severity Assessment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6, e2315174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nocker, Y.L.; Toolan, C.K. Using Telehealth to Provide Interventions for Children with ASD: A Systematic Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 10, 82–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, A.V.; Ruble, L.; Kuravackel, G.; Scarpa, A. Efficacy of a telehealth parent training intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: Rural versus urban areas. Evid.-Based Practice Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 7, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, B.; Shannon, K.; Berger, N.; Pickard, K.; Holtz, B. Self-directed telehealth parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder: Examination of the potential reach and utilization in community settings. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Chua, J.D. Telehealth Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder Communities. JAACAP Connect 2025. Available online: https://jaacapconnect.org/article/129957-telehealth-interventions-for-autism-spectrum-disorder-communities (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Emerson, E. Poverty and people with intellectual disabilities. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Boyce, W.T.; McEwen, B.S. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA 2009, 301, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, N.; Houtrow, A.; Larson, K.; Newacheck, P.W. The changing landscape of disability in childhood. Future Child. 2012, 22, 13–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, D.M.; Geschwind, D.H. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2013, 26, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scal, P.; Ireland, M. Addressing transition to adult health care for adolescents with special health care needs. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; O’Hare, K.; Antonelli, R.C.; Sawicki, G.S. Transition care: Future directions in education, health policy, and outcomes research. Acad. Pediatr. 2014, 14, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemly, D.C.; Weitzman, E.R.; O’Hare, K. Advancing healthcare transitions in the medical home: Tools for providers, families and adolescents with special healthcare needs. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013, 25, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, G.; Law, M.; King, S.; Rosenbaum, P. Parents’ and service providers’ perceptions of the family-centredness of children’s rehabilitation services. In Family-Centred Assessment and Intervention in Pediatric Rehabilitation, 1st ed.; King, G., Law, M., King, S., Rosenbaum, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidullah, J.D.; Azad, G.; Mezher, K.R.; McClain, M.B.; McIntyre, L.L. Linking the medical and educational home to support children with autism spectrum disorder: Practice recommendations. Clin. Pediatr. 2018, 57, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Meeting Flourishing Criteria N = 329 Weighted N = 225,667 | Not Meeting Flourishing Criteria N = 1924 Weighted N = 1,233,122 | All N = 2253 Weighted N = 1,458,789 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flourishing variable | 15.5% | 84.5% | 100% |

| Age | |||

| 6–11 | 52.1% | 49.6% | 50.0% |

| 12–17 | 47.9% | 50.4% | 50.0% |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 67.1% | 77.8% | 76.1% |

| Female | 32.9% | 22.2% | 23.9% |

| Race | |||

| White | 50.0% | 52.2% | 51.8% |

| Black | 10.2% | 15.7% | 14.8% |

| Hispanic | 32.4% | 23.0% | 24.4% |

| Other | 7.4% | 9.2% | 8.9% |

| Household poverty level | |||

| 0–99% FPL | 17.4% | 20.0% | 19.6% |

| 100–199% FPL | 22.9% | 28.4% | 27.6% |

| 200–399% FPL | 30.8% | 27.6% | 28.1% |

| 400%+ FPL | 28.8% | 24.0% | 24.8% |

| Parent education level | |||

| Below high school | 33.4% | 30.6% | 31.0% |

| High school | 26.5% | 26.1% | 26.2% |

| Above high school | 40.1% | 43.3% | 42.8% |

| ASD severity | |||

| Mild | 68.1% | 39.7% | 44.1% |

| Moderate/severe | 31.9% | 60.3% | 55.9% |

| General health | |||

| Excellent or very good | 83.2% | 61.2% | 64.6% |

| Good | 15.2% | 29.9% | 27.6% |

| Fair or poor | 1.6% | 8.9% | 7.8% |

| Adverse childhood experiences | |||

| 0–1 | 77.0% | 52.8% | 56.5% |

| 2 or more | 23.0% | 47.2% | 43.5% |

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| System of care | ||

| Receive care in a well-functioning system (vs. without such care) | 1.517 (1.495–1.540) | <0.001 |

| Age | ||

| 12–17 (vs. 6–11) | 1.209 (1.197–1.222) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Female (vs. male) | 1.581 (1.564–1.598) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||

| Black (vs. White) | 0.940 (0.925–0.956) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic (vs. White) | 1.579 (1.561–1.598) | <0.001 |

| Other (vs. White) | 1.002 (0.984–1.021) | 0.7934 |

| Household poverty Level | ||

| 0–99% FPL (vs. 400+) | 0.717 (0.704–0.729) | <0.001 |

| 100–199% FPL (vs. 400+) | 0.733 (0.722–0.744) | <0.001 |

| 200–399% FPL (vs. 400+) | 0.894 (0.881–0.906) | <0.001 |

| Parent Education Level | ||

| High school (vs. below) | 0.808 (0.797–0.819) | <0.001 |

| Above high school (vs. below) | 0.484 (0.477–0.491) | <0.001 |

| ASD Severity | ||

| Moderate/severe (vs. mild) | 0.381 (0.377–0.385) | <0.001 |

| General Health Status | ||

| Excellent or very good (vs. fair or poor) | 6.334 (6.120–6.556) | <0.001 |

| Good (vs. fair or poor) | 2.507 (2.418–2.598) | <0.001 |

| Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) | ||

| 2 or more (vs. 0–1) | 0.417 (0.413–0.422) | <0.001 |

| System of Care | Odds Ratio (95% CI) * | p |

|---|---|---|

| Families are partners in decision making | ||

| Yes (vs. no) | 2.280 (2.216–2.346) | <0.001 |

| Current insurance is adequate | ||

| Yes (vs. no) | 1.768 (1.747–1.789) | <0.001 |

| Care meets medical home criteria | ||

| Yes (vs. no) | 1.221 (1.209–1.233) | <0.001 |

| Having preventive care visits | ||

| Yes (vs. no) | 0.853 (0.511–1.425) | 0.5434 |

| Unmet needs and frustration | ||

| No (vs. experienced some) | 1.726 (1.698–1.753) | <0.001 |

| Received services to prepare for transition ** | ||

| Yes (vs. no) | 2.075 (2.039–2.113) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Reszka, S. Linking System of Care Services to Flourishing in School-Aged Children with Autism. Disabilities 2025, 5, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020057

Zhang W, Reszka S. Linking System of Care Services to Flourishing in School-Aged Children with Autism. Disabilities. 2025; 5(2):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020057

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wanqing, and Stephanie Reszka. 2025. "Linking System of Care Services to Flourishing in School-Aged Children with Autism" Disabilities 5, no. 2: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020057

APA StyleZhang, W., & Reszka, S. (2025). Linking System of Care Services to Flourishing in School-Aged Children with Autism. Disabilities, 5(2), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities5020057