Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Services for Young Women with and Without Disabilities During a Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Background

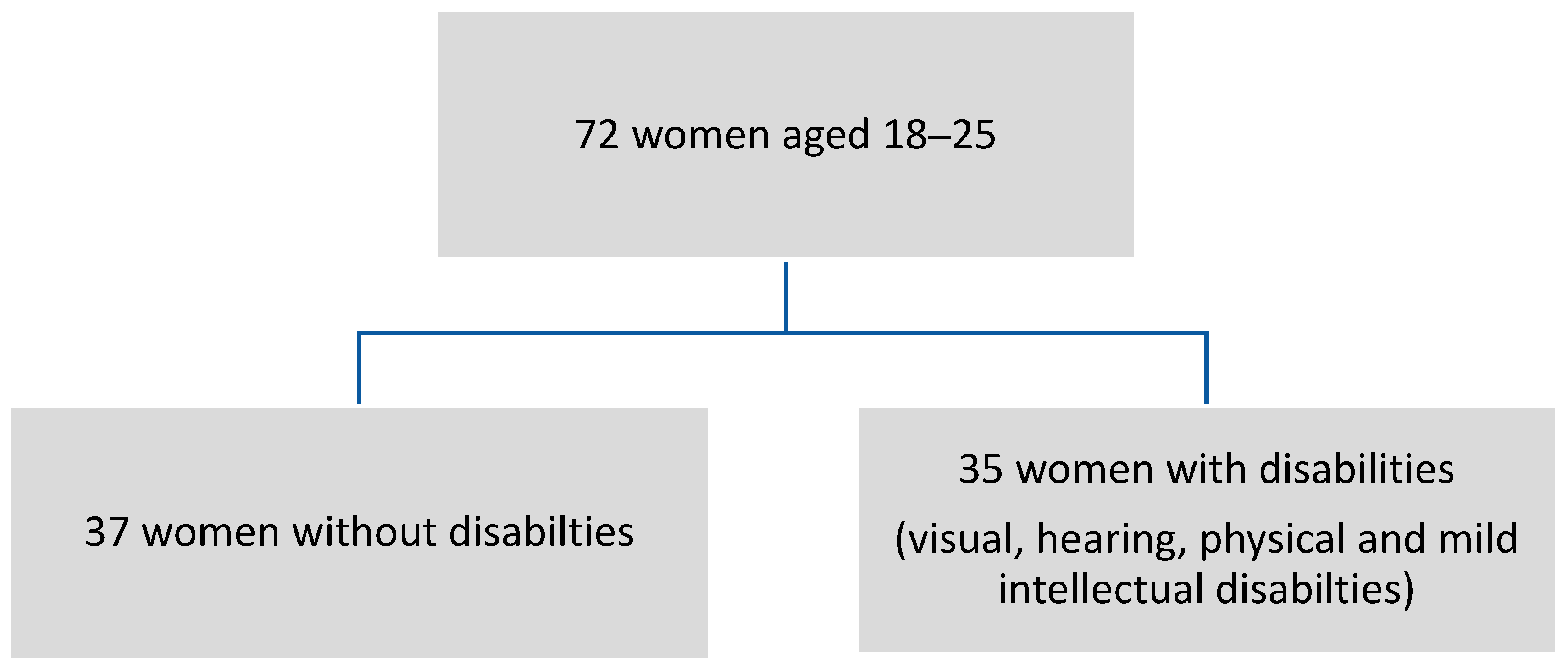

2.2. Sampling

- (1)

- being female aged ≥18 to 25,

- (2)

- completed studies (within the last year) or enrolled in a tertiary institution,

- (3)

- willing to self-report on their sexual reproductive health, sexuality, and experience of the COVID-19 lockdown and its impact on their lives,

- (4)

- able to understand an accessible version of the questionnaire, and

- (5)

- conversant in English, isiZulu, or sign language.

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Accessing Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRHR) Services and Commodities

SRHR Service Usage

“It didn’t continue (going to SRHR services) … it was PrEP and prevention pills, during level 5 I didn’t really go get my pills. I didn’t go to the clinic unless I felt …. I was not sexually active, so I was just like I’m not going to go for my contraceptives or my PrEP pills.”(23-year old woman without disabilities, strict lockdown)

“I didn’t access contraceptives during level 5 and 4 because I was not sexually active.”(23-year old woman with intellectual disability, strict lockdown)

“Accessing the clinic was difficult because the queues were very long. I just left and went back home.”(20-year old Deaf woman, strict lockdown)

“They [nurses] took COVID-19 patients more [seriously] so they were the essential patients rather than us who came for injection and other prevention methods, they said it is not essential, they don’t take it serious, if you want to prevent come back after the pandemic is lowered down.”(23-year-old woman without disability, strict lockdown)

“I did not go to the clinic …some of my appointments were postponed because of COVID-19, especially level 4 & 5. It was critical that time.”(20-year old blind woman, strict lockdown)

“It is actually very helpful when staff (at the campus clinics) is friendly because you get to ask more questions, you find out more such as PrEP (Pre-exposure Prophylaxis) even if you didn’t know about it, because the person is friendly you get to ask for information …, whereas back home you find that they (clinic staff) are shouting at you or complaining about this and this…you go there … they are not giving you proper instructions, it becomes difficult, you just want to do whatever you are there for and then leave. You will not even say let me do an HIV test, you just gonna want to be out of the place as soon as possible.”(23-year old woman without disability, strict lockdown)

The clinics nurses say that a “girl should stay pure and it is not easy to go to the clinic to access SRHR services, they will look at you with a devils eye.”(19-year-old woman without disability, strict lockdown)

“My boyfriend buys condoms from shops. I sometimes have sex without condoms—skin to skin—because I won’t go to the clinic [community public health care] because the nurses won’t help me.”(25-year-old Deaf woman, soft lockdown)

SRHR Commodities

“I did not even ask about it [contraceptives] I just said I will continue when I am back in Durban. … during level 5 [2020] I didn’t really go to get my pills. I didn’t go to the clinic, I was not sexually active, so I was not going to go for my contraceptives or my PrEP pills.”(25-year-old woman without disability, strict lockdown)

“During the lockdown level 4 in 2020, everything was hard like getting contraceptive, injections or pills. There was a free box of condoms there (clinic) that you can help yourself. I fear of getting pregnant, so I use condoms.”(22-year old Deaf woman, strict lockdown)

“I get free condoms from the clinic. If none there, I will either buy them from the shops or get one from a friend.”(24-year old Deaf woman, soft lockdown)

“I had no challenges obtaining sanitary pads. There were people from the Department of Health who were distributing pads around my home, at bus stops, halls and mobile clinics.”(21-year-old woman without disability, strict lockdown)

“I was using sanitary pads that my aunt bought me and had no problem getting them.”(22-year old woman with intellectual disability, strict lockdown)

“I buy period pads from the shops not the clinic. Why because it’s not the same and it [the pads from the clinic] is very uncomfortable and too big.”(24-year old deaf women, soft lockdown)

3.2.2. Disability Related Barriers to SRHR Services

At the clinic, the nurses don’t know sign language and there were no interpreters to help me. The only option was to write on paper to ask for something. Even that was hard because my written English was limited and even the nurses battled to understand me. I was worried about wrong information and miscommunication. Very stressful.(23-year old Deaf women, before lockdown)

“At the clinic, sometimes, they do not have injections, and this is why I started going to the doctor, I would rather pay money—I would rather pay money than to go for nothing.”(20-year old blind woman, soft lockdown)

“I stopped using the 3-month-depo in September (2020) because I went to the clinic and when I arrived at the clinic I was told there were no more 3-month-depo injections—I went to another clinic and I got a big problem there, they told me to take off my panty as they wanted to see if I am bleeding, it was wrong and they told me they couldn’t give me because I am not bleeding, when I went to another clinic they ask me where I stay and why I didn’t go to the clinic in my area.”(24-year old woman with physical disability, soft lockdown)

“I used 3 Month Depo and then practiced early withdrawal and accessed medication (emergency contraceptives) from the pharmacy for cleaning myself from sperm.”(24-year old woman with physical disability, soft lockdown)

“When I got to the clinic I reported my illness but they did not check anything and only handed me pills, I drank the pills as there was nothing much I could do, the pills did not help me and I landed up in hospital. They just gave me pills without checking what was wrong with me. I got to the hospital I was told that I have got an infection and they injected me and gave me more pills.”(24-year old woman with physical disability, soft lockdown)

“…I accessed these services at the (University name) clinic and staff was very helpful and explained everything I needed to know. … They said I made the best decision, and they were very gentle.”(21-year-old blind woman, before lockdown)

“It [support from family members] helps but without them it [communicating with health care staff] is very difficult.”(24-year-old Deaf woman, before and during lockdown)

“My mother took me to the clinic to have an HIV test and was negative. My mother wanted to check on me to see if I had sex or not because I was studying in Cape Town for two years, far away from her.”(22-year old Deaf woman, before lockdown)

“Before COVID I got the 3-month injection, I point to it on a poster, now I buy condoms and practice early withdrawal to prevent falling pregnant.”(25-year-old deaf woman, soft lockdown)

“I only went for HIV and TB test. The nurses were ok but no patience though. The nurses always say hurry up because the queues are long. They don’t have time to understand or take trouble with me. I am very disappointed. I communicate on paper, very simple like WANT HIV OR TB TEST, NEGATIVE OR POSTIVE?”(22-year-old deaf woman, soft lockdown)

“My sister comes with me to the clinic to help to communicate with the nurses for me. It is easier that way. If I go by myself it is a lot harder, no sign language there. Can’t lipread because of the mask. I can write on paper, but my written English can also be confusing or misunderstanding.”(23-year-old deaf woman, soft lockdown)

3.2.3. Experiences of Partner and Non-Partner Violence and Accessing Support

“…when I was visiting him, … he said I must open my phone and when I refused to open my phone because he doesn’t open his phone for me … then he slapped me, beat me and threatened to stab me. He said I must open my phone and he smashed my phone.”(19-year-old woman without disability, soft lockdown)

“He assaulted, raped me in the student residence because I do not have the power and strength to fight him, …. the security guard said that she cannot do anything (take a report) because I signed him out … I felt so dirty … my friend didn’t believe me … and I had to have another operation as the rape loosened the screws in my hip.”(25-year-old woman with a physical disability, before lockdown)

“While visiting my mom in the Eastern Cape her boyfriend attempted to have sex with me, but I refused. My mom came in while he was in bed with me trying to force me to have sex with him. I was taken to the clinic for a checkup. He was not arrested, and I did not go back to Eastern Cape, I don’t like going there because of what happened…The second incident happened when I was raped by my cousin, I fell pregnant and later terminated the pregnancy.”(25-year-old woman with intellectual disability, soft lockdown)

During COVID-19 everything was more stressful. My boyfriend insulted, humiliated me, and yelled at me. Sometimes the physical abuse included slapping and sex without consent and humiliating sexual activities. He goes on a Friday to drink and comes back home drunk. He hadn’t been like that before the COVID pandemic. One night he hurt me so bad that he had to take me to the clinic the next day. There was no counseling available as there was no interpreter.(22-year-old deaf woman, soft lockdown)

“My line manager stopped harassing me after I confronted him, but he was thereafter rude and found the faults in my work. …I just wanted my contract to come to an end … one of my colleagues advised me that the next time I go to his office I must try and record him so I can have more evidence because previously one colleague reported this manager and the victim lost the case because of not enough evidence.”(22-year-old woman with intellectual disability, soft lockdown)

My mother would shout at me and I feel suppressed by her. My mother resents me because I am broken (deaf), I cannot communicate with her and she forces me to clean and cook. My mother would shout at me to cook and make ‘bad facial expressions’ to show me hear disapproval.(22-year-old deaf woman, strict lockdown)

“Something had happened at home and I did not acknowledge it, when I was confronted about it, since I have got a tendency to roll my eyes, I rolled my eyes and looked at my mother up and down, my father asked me why I rolled my eyes at my mother, which was when he back slapped me and then I cried…You know how parents are when they hit you, it is like they are putting you in shape or they are fixing you, so I did not take it as abuse.”(21-year-old woman with intellectual disability, strict lockdown)

“My mother often slaps my face. I also fought with my older sister. I never told anyone or reported them. I kept everything to myself, I don’t want problems—miscommunication and people won’t believe me. I suffer quietly … My ex-boyfriend treated me badly. I kept quiet about it because if I told someonemy ex-boyfriend would find out and would hurt me, worse than before. I never went for counseling because there is no interpreter to help me. They also don’t know the Deaf culture. They won’t understand.”(24-year-old Deaf woman, strict lockdown)

“He raped me and slapped me and I then reported him to my aunt and told her what he had done to me. He denied it. My aunt then told the rest of the family and they said he is supposed to do a cleansing ceremony, but I don’t want anything to do with him. It’s ok even if he is not arrested… I am not sure where I contracted HIV.”(24-old woman with intellectual disability, soft lockdown, who terminated pregnancy)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNFPA Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: An Essential Element of Universal Health Coverage; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- South African National AIDS Council. National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2023–2028; SANAC: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.; Dorrington, R.A. Model for Evaluating the Impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa; Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Research; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kularatne, R.S.; Niit, R.; Rowley, J.; Kufa-Chakezha, T.; Peters, R.P.H.; Taylor, M.M.; Johnson, L.F.; Korenromp, E.L. Adult gonorrhoea, chlamydia and syphilis prevalence, incidence, treatment and syndromic case reporting in South Africa: Estimates using the Spectrum-STI model, 1990–2017. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathebula, R.; Kuonza, L.; Musekiwa, A.; Kularatne, R.; Puren, A.; Reubenson, G.; Sherman, G.; Kufa, T. Trends in RPR seropositivity among children younger than 2 years in South Africa, 2010–2019. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmab017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South African Police Services. Police Recorded Crime Statistics, Republic South Africa. 2021/2022 Financial Year. Available online: https://www.saps.gov.za/services/downloads/Annual-Crime-2021_2022-web.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- South African National Department of Health. South Africa demographic and health survey 2016: Key findings. In Key Indicators Report 2016; NdoH: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Machisa, M.T.; Christofides, N.; Jewkes, R. Mental ill health in structural pathways to women’s experiences of intimate partner violence. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. The Young and the Restless-Adolescent Health in South Africa. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=15261 (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Hanass-Hancock, J.; Murthy, G.; Palmer, P.; Pinilla-Roncancio, M.; Rivas Velarde, M.; Mitra, S. The Disability Data Report 2023; Disability Data Initiative; Fordham Research Consortium on Disability: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S.; Yap, J. The Disability Data Report 2022; Disability Data Initiative; Fordham Research Consortium on Disability: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, C.S. Disability Rights During the Pandemic. A Global Report on Findings of the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor. Validity, ENIL, IDA, DRI, CfHR, IDDC, DRF, 2020. Available online: https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/disability_rights_during_the_pandemic_report_web_pdf_1.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Kuper, H.; Hanass-Hancock, J. Framing the debate on how to achieve equitable health care for people with disabilities in South Africa. South Afr. Health Rev. 2020, 2020, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA. The impact of COVID-19 on women and girls with disabilities. In A Global Assessment and Case Studies on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, Gender-Based Violence, and Related Rights; UNFPA: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg, S.; Smythe, T.; Kuper, H. Left behind: Modelling the life expectancy disparities amongst people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ 2023, in press. [Google Scholar]

- The Missing Billion Initiative; Clinton Health Access Initiative. Reimagining Health Systems. That Expect, Accept and Connect 1 Billion People with Disabilities; MBI and CHAI: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d79d3afbc2a705c96c5d2e5/t/634d9409d12381407c9c4dc8/1666028716085/MBReport_Reimagining+Health+Systems_Oct22 (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Braathen, S.H.; Carew, M.T.; Chiwaula, M.; Rohleder, P. Physical disability and sexuality, some history and some findings. In Physical Disability and Sexuality Stories from South Africa; Hunt, X., Braathen, S.H., Chiwaula, M., Carew, M.T., Pohleder, P., Swartz, L., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2021; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation; UNFPA. Promoting Sexual and Reproductive Health for Persons with Disabilities; Guidance Note; WHO/UNFPA: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Beaudrap, P.; Beninguisse, G.; Pasquier, E.; Tchoumkeu, A.; Touko, A.; Essomba, F.; Brus, A.; Aderemi, T.J.; Hanass-Hancock, J.; Eide, A.H.; et al. Prevalence of HIV infection among people with disabilities: A population-based observational study in Yaoundé, Cameroon (HandiVIH). Lancet-HIV 2017, 4, e161–e168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBeaudrap, P.; Beninguisse, G.; Mouté, C.; Temgoua, C.D.; Kayiro, P.C.; Nizigiyimana, V.; Pasquier, E.; Zerbo, A.; Barutwanayo, E.; Niyondiko, D.; et al. The multidimensional vulnerability of people with disability to HIV infection: Results from the handiSSR study in Bujumbura, Burundi. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 25, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shisana, O.; Rehle, T.; Simbayi, L.C.; Zuma, K.; Jooste, S.; Zungu, N.; Labadarios, D.; Onoya, D. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012; HSRC: Cape Town, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle, K.; Van der Heijden, I.; Stern, E.; Chirwa, E. Disability and Violence Against Women and Girls Global Programme; What Works: London, UK, 2018.

- UNFPA. The right to access. In Regional Strategic Guidance to Increase Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) for Young Persons with Disabilities in East and Southern Africa; UNFPA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Needs Assessment on the Current State of CSE for Young People with Disabilities in the East and Southern African Region; UNESCO: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hanass-Hancock, J. Disability and HIV/AIDS—A Systematic Review of Literature in Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2009, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanBenschoten, H.; Kuganantham, H.; Larsson, E.C.; Endler, M.; Thorson, A.; Gemzell-Danielsson, K.; Hanson, C.; Ganatra, B.; Ali, M.; Cleeve, A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to and utilisation of services for sexual and reproductive health: A scoping review. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelekan, T.; Mihretu, B.; Mapanga, W.; Nqeketo, S.; Chauke, L.; Dwane, Z.; Baldwin-Ragaven, L. Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on family planning utilisation and termination of pregnancy services in Gauteng, South Africa: March–April 2020. Wits J. Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, R.; Castle, S.; Hensen, B. I feel that things are out of my hands. How COVID-19 Prevention Measures Have Affected Young People’s Sexual and Reproductive Health in Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Nepal and Zimbabwe; Rutgers: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, A.; Kantorova, V.; Ueffing, P. The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on meeting needs for family planning: A global scenario by contraceptive methods used. Gates Open Res. 2020, 4, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFPA. Young People’s Access and Barriers to SRHR Services in South Africa; Evidence Brief; UNFPA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, V.; Mulwa, S.; Khanyile, D.; Sarrassat, S.; O’Donnell, D.; Piot, S.; Diogo, Y.; Arnold, G.; Cousens, S.; Cawood, C.; et al. Young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health prevention services in South Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online questionnaire. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2023, 7, e001500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, R.; Day, C.; Deghaye, N.; Nkonki, L.; Rensburg, R.; Smith, A.; van Schalkwyk, C. Examining the Unintended Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Public Sector Health Facilit Visits: The First 150 Days; National Income Dynamics Study, Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey: Stellenbosh, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, E.L.; McKinney, V.; Swartz, L. South Africa: Bad at any time, worse during COVID-19? S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2021, 19, e1–e5. [Google Scholar]

- Rohwerder, B.; Njungi, J.; Wickenden, M.; Thompson, S.; Shaw, J. “This Time of Corona Has Been Hard”—People with Disabilities’ Experiences of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Kenya; IDS: Brigthon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wickenden, M.; Shaw, J.; Thompson, S.; Rohwerder, B. Lives turned upside down in COVID-19 times: Exploring disabled people’s experiences in 5 low-and-middle-income countries using narrative interviews. Disabil. Stud. Quaterly 2021, 41, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, M.A.; Mitra, M. COVID-19 and people with disability: Social and economic impacts. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 2101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; Chuba-Uzo, S.; Rohwerder, B.; Shaw, J.; Wickenden, M. “This Pandemic Brought a Lot of Sadness”: People with Disabilities’ Experiences of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria; IDS: Brigthon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J.; Akter, F.; Rohwerder, B.; Wickenden, M.; Thompson, S. “Everything is Totally Uncertain Right Now”: People with Disabilities’ Experiences of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh; IDS: Brigthon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, L. Crisis Talks. Raising the Global Voice of Youth with Disabilities on the COVID-19 Pandemic; Leonard Cheshire: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, X. The Health of People with Disabilities in Humanitarian Settings During the COVID-19 Pandemic. IDS Bull. 2022, 53, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARRC. In the Daily Life of Adolescent Girls and Young Women (AGYW) with Disabilities—Evidence Gathering for AGYW Policy and Advocacy; Afrique Rehabilitation and Research Consultants: Cape Town, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hanass-Hancock, J.; Nzuza, A.; Willan, S.; Padayachee, T.; Machisa, M.; Carpenter, B. Livelihoods and young women with and without disabilities in KwaZulu-Natal during COVID-19. AJOD 2024, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Section27. Letter to Minister for Health Re: Protecting Safe Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services During COVID-19 Pretoria 2020. Available online: http://section27.org.za/2020/04/letter-to-minister-for-health-re-protecting-safe-access-to-sexual-and-reproductive-health-services-during-covid-19/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Hunter, Q.; Singh, K.; Wicks, J. Eight days in July. In Inside the Zuma Unrest That Set South Africa Alight; Tafelberg: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- STATS, SA. South African Demographic and Health Survey 2016; Key Indicator Report; Stats SA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- IPPF; UNFPA; World Health Organisation. Rapid Assessment Tool for Sexual & Reproductive Health and HIV Linkages: A Generic Guide; IPPF: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2011. Statistical Release—P0301.4; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012.

- Zhang, W.; O’brien, N.; Forrest, J.I.; Salters, K.A.; Patterson, T.L.; Montaner, J.S.G.; Hogg, R.S.; Lima, V.D. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, T.; Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Deitchler, M. Household Hunger Scale: Indicator Definition and Measurement Guide; FANTA, Tufts University, FAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; World Health Organisation, LSHTM, SAMRC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, L.M.; Willan, S.; Inglis-Jassiem, G.; Dunkle, K.; Shakespeare, T.; Hameed, S.; Ganle, J.; Machisa, M.; Carpenter, B.; Mthethwa, N.; et al. Including people with disabilities in research under COVID-19: Experiences from the field. IDS Bull. 2022, 53, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hensen, B.; Gondwe, M.; Phiri, M.; Schaap, A.; Simuyaba, M.; Floyd, S.; Mwenge, L.; Sigande, L.; Shanaube, K.; Simwinga, M.; et al. Access to menstrual hygiene products through incentivized, community-based, peer-led sexual and reproductive health services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the Yathu Yathu trial. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, e554. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.N.; Milkovich, R.; Thiongo, M.; Byrne, M.E.; Devoto, B.; Wamue-Ngare, G.; Decker, M.R.; Gichangi, P. Product-access challenges to menstrual health throughout the COVID-19 pandemic among a cohort of adolescent girls and young women in Nairobi, Kenya. Eclinical Med. 2022, 49, e101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kgware, M. Menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene Management in Selected KwaZulu-Natal Schools; OXFAM: Durban, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Development. Elements of the Financial and Economic Costs of Disability to Households in South Africa; Results from a Pilot Study; DSD South Africa: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015.

- National Student Financial Aids Scheme. The DHET Bursary Scheme Pretoria: NSFAS; 2023. Available online: https://www.nsfas.org.za/content/bursary-scheme.html (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Kuper, H.; Heydt, P. The missing billion. In Access to Health Services for 1 Billion People with Disabilities; London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, A.H.; Mannan, H.; Khogali, M.; van Rooy, G.; Swartz, L.; Munthali, A.; Hem, K.-G.; MacLachlan, M.; Dyrstad, K. Perceived Barriers for Accessing Health Services among Individuals with Disability in Four African Countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Women Youth and Persons with Disabilities, United Nations Human Rights. COVID-19 and rights of persons with disabilities. In The Impact of COVID-19 on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in South Africa; DWYPD: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bulbulia, Z. Persons with Disability under COVID-19 in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 23rd International AIDS Conference, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; AIDS: Global Village, Dubai, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA. Gender-based violence and COVID-19. In Actions, Gaps and Ways Forward; UNFPA: Sunninghill, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, M. The Changing Political Economy of Sex in South Africa: The significance of unemployment and inequalities to the scale of the AIDS pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Heijden, I.; Abrahams, N.; Harries, J. Additional layers of violence: The intersections of gender and disability in the violence experiences of women with physical disabilities in South Africa. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 826–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, I.; Harries, J.; Abrahams, N. In pursuit of intimacy: Disability stigma, womanhood and intimate partnerships of South Africa. Cult. Health Sex. 2018, 21, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARRC. Things to know about: Sexual transmitted infections (STIs). In For People with and Without Disabilities; ARRC: Cape Town, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ARRC. Things to know about: Human immunodeficient virus (HIV). In For people with and Without Disabilities; ARRC: Cape Town, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ARRC. Things to know about: Violence and abuse. In For People with and Without Disabilities; ARRC: Cape Town, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- AIDS Foundation South Africa. Adolescent and Young People Programme Description; Final Version (05); AFSA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Pre-COVID-19 | Strict Lockdown | Soft Lockdown | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | ||

| n | 37 | 35 | 37 | 35 | 29 | 27 | |

| Age in 2020 (mean (SD)) | 21.38 (2.52) | 22.00 (2.00) | |||||

| Student in 2020 (%) | 31 (83.8) | 33 (94.0) | |||||

| Number of intimate partners in the past year (mean (SD)) | 1.46 (0.69) | 1.51 (1.87) | 1.14 (0.45) | 2.00 (2.38) | 1.11 (0.32) | 0.74 (0.53) | ## |

| Currently in an intimate relationship = Yes (%) | 28 (75.7) | 18 (51.4) | 28 (75.7) | 18 (51.4) | 19 (65.5) | 18 (66.7) | *, ^^^ |

| Living with main intimate partner = Yes (%) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CES-D Score (mean (SD)) | 15.86 (6.49) | 14.80 (5.54) | 11.03 (4.71) | 11.33 (5.09) | |||

| CES-D >10 = TRUE (%) | 31 (83.8) | 28 (80.0) | 14 (48.3) | 16 (59.3) | |||

| Number of people living in residence (mean (SD)) | 3.35 (2.29) | 6.69 (8.91) | 5.97 (2.87) | 6.26 (2.62) | 5.52 (3.71) | 4.81 (2.94) | * |

| Type of residence (%) | *** | ||||||

| Separate/backyard dwelling | 15 (40.5) | 28 (80.0) | 37 (100.0) | 34 (97.1) | 27 (93.1) | 25 (92.6) | |

| Student residence | 22 (59.5) | 7 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Experience of COVID-19 symptoms in the last months? = Yes (%) | 24 (64.9) | 19 (54.3) | 15 (51.7) | 14 (51.9) | |||

| Tested for COVID-19 = Yes (%) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (15.8) | 4 (26.7) | 6 (42.9) | |||

| SRHR Services Used/Access During the Period | Pre-COVID-19 | Strict Lockdown | Soft Lockdown | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | ||

| n | 37 | 35 | 37 | 35 | 29 | 27 | |

| Family Planning and contraceptives = Yes (%) | 21 (56.8) | 16 (45.7) | 12 (32.4) | 10 (28.6) | 13 (44.8) | 10 (37.0) | |

| Prevention and management of Sexually transmitted infection = Yes (%) | 23 (62.2) | 14 (40.0) | 9 (24.3) | 7 (20.0) | 13 (44.8) | 5 (18.5) | # |

| Prevention and management of gender-based violence = Yes (%) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (8.6) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (8.6) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Prevention of unsafe abortion and management of post-abortion care = Yes (%) | 5 (13.5) | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HIV Testing and Counseling = Yes (%) | 30 (81.1) | 18 (51.4) | 12 (32.4) | 8 (22.9) | 19 (65.5) | 16 (59.3) | * |

| Psycho-social support = Yes (%) | 7 (18.9) | 8 (22.9) | 6 (16.2) | 4 (11.4) | 7 (24.1) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Routine gynecological examination (includes Breast cancer screening, Pap smear and cervical cancer screening) = Yes (%) | 7 (18.9) | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.6) | 1 (3.4) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Pregnancy testing = Yes (%) | 24 (64.9) | 10 (28.6) | 12 (32.4) | 5 (14.3) | 10 (34.5) | 7 (25.9) | ** |

| Antenatal clinic and maternal health services = Yes (%) | 11 (29.7) | 2 (5.7) | 8 (21.6) | 1 (2.9) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (11.1) | *, ^^^ |

| No SRHR service usage (%) | 3 (8.1) | 8 (22.9) | 13 (35.1) | 16 (45.7) | 3 (10.3) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Pregnancy Prevention Methods Applied in the Period | Pre-COVID-19 | Strict Lockdown | Soft Lockdown | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | ||

| n | 37 | 35 | 37 | 35 | 29 | 27 | |

| IUD (intrauterine devices) = Yes (%) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| INJECTABLES—3 MONTH DEPO = Yes (%) | 10 (27.0) | 11 (31.4) | 4 (10.8) | 6 (17.1) | 2 (6.9) | 8 (29.6) | # |

| INJECTABLES—2 MONTH NUR-ISTERATE = Yes (%) | 5 (13.5) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (11.1) | |

| IMPLANTS = Yes (%) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PILL = Yes (%) | 3 (8.1) | 4 (11.4) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.7) | 4 (13.8) | 3 (11.1) | |

| MALE CONDOM = Yes (%) | 30 (81.1) | 22 (62.9) | 20 (54.1) | 12 (34.3) | 19 (65.5) | 17 (63.0) | |

| EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION = Yes (%) | 18 (48.6) | 7 (20.0) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (2.9) | 7 (24.1) | 5 (18.5) | * |

| Periodic abstinence = Yes (%) | 16 (43.2) | 11 (31.4) | 12 (32.4) | 6 (17.1) | 4 (13.8) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Early withdrawal = Yes (%) | 20 (54.1) | 19 (54.3) | 10 (27.0) | 10 (28.6) | 9 (31.0) | 9 (33.3) | |

| Other (IUD/female condom) = Yes (%) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (7.4) | |

| No contraceptive method (not including abstinence or withdrawals) = Yes (%) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (25.7) | 11 (29.7) | 18 (51.4) | 5 (17.2) | 7 (25.9) | *** |

| Menstrual Hygiene Products Used During the Period | Pre-COVID-19 | Strict Lockdown | Soft Lockdown | p 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | ||

| n | 37 | 35 | 37 | 35 | 29 | 27 | |

| Disposable sanitary pad = Yes (%) | 35 (94.6) | 34 (97.1) | 32 (86.5) | 33 (94.3) | 27 (93.1) | 23 (85.2) | |

| Reusable pad = Yes (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Menstrual cloth = Yes (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Tampon = Yes (%) | 9 (24.3) | 3 (8.6) | 7 (18.9) | 4 (11.4) | 4 (13.8) | 5 (18.5) | |

| Menstrual cup = Yes (%) | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other = Yes (%) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.7) | |

| Types of Violence | Pre-COVID-19 | Strict Lockdown | Soft Lockdown | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | Women Without Disability | Women with Disability | ||

| n | 37 | 35 | 37 | 35 | 29 | 27 | |

| Non-partner physical violence = Yes (%) | 3 (8.1) | 4 (11.4) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (11.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Non-partner sexual violence = Yes (%) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Intimate partner emotional violence = Yes (%) | 6 (16.2) | 6 (17.1) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (8.6) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Intimate partner physical violence = Yes (%) | 3 (8.1) | 6 (17.1) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | |

| Intimate partner sexual violence = Yes (%) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | * |

| Any non-partner violence = Yes (%) | 3 (8.1) | 6 (17.1) | 1 (2.7) | 5 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Any intimate partner violence = Yes (%) | 8 (21.6) | 6 (17.1) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (8.6) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (11.1) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hanass-Hancock, J.; Nzuza, A.; Padayachee, T.; Dunkle, K.; Willan, S.; Machisa, M.T.; Carpenter, B. Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Services for Young Women with and Without Disabilities During a Pandemic. Disabilities 2024, 4, 972-995. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040060

Hanass-Hancock J, Nzuza A, Padayachee T, Dunkle K, Willan S, Machisa MT, Carpenter B. Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Services for Young Women with and Without Disabilities During a Pandemic. Disabilities. 2024; 4(4):972-995. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanass-Hancock, Jill, Ayanda Nzuza, Thesandree Padayachee, Kristin Dunkle, Samantha Willan, Mercilene Tanyaradzwa Machisa, and Bradley Carpenter. 2024. "Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Services for Young Women with and Without Disabilities During a Pandemic" Disabilities 4, no. 4: 972-995. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040060

APA StyleHanass-Hancock, J., Nzuza, A., Padayachee, T., Dunkle, K., Willan, S., Machisa, M. T., & Carpenter, B. (2024). Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Services for Young Women with and Without Disabilities During a Pandemic. Disabilities, 4(4), 972-995. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040060