Qualitative Study to Identify the Training and Resource Needs of Secondary School Teachers in Responding to Students with SEN and SENS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Training

3.1.1. Emotional Education

3.1.2. Technology and Resources

“…It is important to acquire more training in ICT in order to deal with these new situations…”PROF-33.

“…It is necessary to continue being trained in the use of ICT adapted to students with functional diversity…”PROF-15.

“…Teaching staff request more training in specific resources for SEN and SENS students from public administration, as what they have at present is insufficient…”PROF-15.

“…Teachers ask the educational administrations for more training in specific resources for students with SEN and SEN, as the training they have is insufficient...”PROF-13.

“…Training in alternative communication systems to facilitate access to curricular content for SENS and SEN students...”PROF-42.

3.1.3. Family

“…Teacher training on strategies for conducting interviews with families, fostering empathy, closeness, enabling relationships of mutual help with families...”PROF-41.

“…Provide training on how to collaborate effectively with families and faculty…”PROF-22.

“…Training on the mastery of skills for affective and effective communication, which will help us to improve communication between teachers, students and family as another pillar that contributes to the emotional wellbeing of the educational community…”PROF-9.

“…The family plays a fundamental role in the learning process of children, and they are a source of support for professionals in educational centres. Without their help we cannot achieve our objective…”PROF-17.

“…In training it is important to include the role that the family plays and their contributions to the school…”PROF-36.

3.1.4. Collaboration

“…sharing work with teachers from a collaborative vision to work in a systematic way…”PROF-2.

“…training in cooperative and collaborative work in a school environment, brings benefits for both students and teachers in promoting diversity and inclusion, improving communication skills…”PROF-9.

3.1.5. Theoretical Foundations

“…we have to be aware of the need for in depth knowledge concerning the characteristics of these students, to be able to give an appropriate response in the educational context. If we do not have in-depth training, we will not be able to achieve our objectives as teachers and we will treat a student without SENS like a SEN student…”PROF-11.

“… I don’t need training in the legal framework. To assist my SEN students, I just need to have knowledge about their disability and their evolutionary development…”PROF-1.

“…Courses on strategies to deal with the different situations that students with diversity may encounter at school and in the classroom…”PROF-20.

“…Clear and precise knowledge of each SEN, as well as intervention guidelines for each of the following: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), intellectual disabilities, visual impairment, hearing impairment, motor impairment, communication and language difficulties…”PROF-35.

“Training in theoretical aspects of diversity and raising awareness of this issue...”PROF-26.

3.1.6. Intervention Strategies

“…I think training on specific strategies for SENS and SEN students is necessary…”PROF-27.

“…Ongoing training in intervention strategies for students with SENS and SEN. This allows us to keep up to date on best practices and evidence-based approaches…”PROF-13.

“…We need training on how to intervene with students with SENS and SEN, guidelines, strategies to identify them, etc.”PROF-36.

“…I consider that it is essential to be trained in teaching-learning strategies aimed at students with SENS and SEN in our autonomous community, …”PROF-43.

3.1.7. Curricular Adaptation

“…Development of materials tailored to the specific needs of students, families and faculty, …”PROF-23.

“…Teachers have to take into account SENS and SEN student characteristics in order to carry out curricular adaptations individually, …”PROF-39.

“…We need material resources adapted to SEN students’ needs…”PROF-2.

3.1.8. Inclusive Practices

“…With the aim of promoting personal integration within the classroom, offer training to help them to work with their group on the sense of belonging of their students, …”PROF-2.

“…it is necessary that teachers and students accept diversity in the classroom, …”PROF-14.

“… Activities to promote SENS and SEN students’ inclusion are needed…”PROF-16.

3.1.9. Awareness Training for SENS and SEN Students

“… receive training that offers teachers a different perspective in their approach to SENS students, and more specifically SEN students, that helps them to develop empathy and connect with their students, …”PROF-2.

“…Teachers should promote positive and tolerant attitudes towards their students, particularly those with SENS and SEN…”PROF-23.

3.2. Personal Resources Dimension

“Participation of SENS specialist teachers in meetings about Tutorial Action Plans, coordination spaces not only in the CCP or department meetings but also in teaching teams, spaces for welcoming students, teachers, and families, …”PROF-2.

“…Strengthen the Zone EOEPs and the Specific EOEPs, not only in terms of staff but also in terms of material…”PROF-42.

3.3. Material Resources Dimension

“…apps and ICT have become normalised and are already a part of our reality. This fact in an increasing reality and has opened up new possibilities for the school…”PROF-19.

“…To have the technological resources that allow us to be in continuous contact with families and students (WEBEX, school blog, Gsuite…). The centre has to be sure about the technological resources that families have at home, …”PROF-30.

“…Adaptation of materials for diversity among the student body in general and in particular for SEN and SENS students, …”PROF-9.

“…spaces and digital educational resources with easy access and use. From virtual classrooms, platforms such as educational applications, communication tools, that is to say, the use of tools that allow for effective and safe contact with students and families, …”PROF-9.

3.4. Relationships between the Three Dimensions of This Study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Organización de Naciones Unidas. Transformar Nuestro Mundo: La Agenda 2030 Para el Desarrollo Sostenible; ONU: Nueva York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/es/2030agenda (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Quintero, J.; Baldiris, S.; Rubira, R.; Cerón, J.; Velez, G. Augmented reality in educational inclusion. A systematic review on the last decade. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 467496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainscow, M. Inclusión educativa: Una agenda de reforma global. Cuad. Pedagog. 2021, 526, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sider, S.; Ainscow, M.; Carington, S.; Shields, C.; Mavropoulou, S.; Nepal, S.; Daw, K. Educación inclusiva en Inglaterra, Australia, Estados Unidos y Canadá: Quo Vadis? Except. Educ. Int. 2024, 34, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Informe de Seguimiento de la Educación en el Mundo, 2020: Inclusión y Educación: Todos y Todas Sin Excepción; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, M.P.B.; Hartman, M.; Wang, Y. Inclusion and special education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tlili, A.; Nascimbeni, F.; Burgos, D.; Huang, R.; Chang, T.; Jemni, M.; Khribi, M.K. Accessibility within open educational resources and practices for disabled learners: A systematic literature review. Smart Learn. Env. 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. BOE nº 340, de 30 de diciembre de 2020. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Sicilia, G.; Simancas, R. Eficiencia y equidad educativa en España: Un análisis comparativo a nivel regional. Hacienda Pública Española/Rev. Public Econ. 2023, 245, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepillo Galvín, M.; Zebda, S. El plan de acción de integración e inclusión de la UE (2021–2027) y su aplicación en España. In Políticas Públicas en Defensa de la Inclusión, la Diversidad y el Género IV; Yurrebaso Macho, A., Seixas Vicente, I., Cabezas Vicente, M., Eds.; Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2021; pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataller, M.; Pla-Viana, L.; Villaescusa, M. Cómo movilizamos al profesorado, desde la formación, para la transformación de los centros. In Acompañar la Inclusión Escolar; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant, D.; Marcelo García, C. Formación inicial del profesorado: Modelo actual y llaves para el cambio. REICE. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio En Educ. 2021, 19, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunga Díaz, T.O. La importancia de la inteligencia emocional en la práctica docente. Cent. Sur. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F.; García, I.; Expósito, E. Formación inicial y formación permanente del profesorado de educación secundaria en España. Bordón Rev. Pedagog. 2021, 73, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden EDU/3498/2011, de 16 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Orden ECI/3858/2007, de 27 de diciembre, por la que se establecen los requisitos para la verificación de los títulos universitarios oficiales que habiliten para el ejercicio de las profesiones de Profesor de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria y Bachillerato, Formación Profesional y Enseñanzas de Idiomas. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2011/12/16/edu3498 (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Orden ECI/3858/2007, de 27 de diciembre, por la que se establecen los requisitos para la verificación de los títulos universitarios oficiales que habiliten para el ejercicio de las profesiones de Profesor de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria y Bachillerato, Formación Profesional y Enseñanzas de Idiomas. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2007/12/27/eci3858/con (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Nieto, J.M.; Alfageme-González, M.B. Enfoques, metodologías y actividades de formación docente. Profesorado. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2017, 21, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Pastor, M.; Van Vaerenbergh, S.; Fernández-Solana, J.; González-Bernal, J.J. Secondary Education Teacher Training and Emotional Intelligence: Ingredients for Attention to Diversity in an Inclusive School for All. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvelo-Rosales, C.N.; Alegre de la Rosa, O.M.; Guzmán-Rosquete, R. Initial training of primary school teachers: Development of competencies for inclusion and attention to diversity. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, P.; Calvo Álvarez, M.I.; Orgaz Baz, B. Inclusión educativa. Actitudes y estrategias del profesorado. Rev. Española Discapac. REDIS 2016, 4, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Felipe-Rello, C.; Garoz Puerta, I.; Tejero-González, C.M. Cambiando las actitudes hacia la discapacidad: Diseño de un programa de sensibilización en Educación Física (Changing attitudes towards disability: Design of an awareness program in Physical Education). Retos. Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2020, 37, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Jiménez, O.; Rodríguez Torres, J.; Cruz Cruz, P. La competencia digital del profesorado y la atención a la diversidad durante la COVID 19. Estudio de caso. Rev. Comun. Salud 2020, 10, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Peris, A.; Mínguez-Alfaro, P.; Martos-García, D. La formación inicial del profesorado de Educación Física: Una mirada desde la atención a la diversidad. Retos 2020, 37, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L. On the necessary co-existence of special and inclusive education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro Contento, K.J.; Erraéz Alvardo, J.L.; Vargas Gaona, M.d.C.; Espinoza Freire, E.E. Consideraciones sobre la educación inclusiva. Rev. Metrop. Cienc. Apl. 2018, 1, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R.; López-Cassá, È. Educación Emocional: 50 Preguntas y Respuestas; Editorial El Ateneo: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cejudo, J.; López-Delgado, M.L. Importancia de la inteligencia emocional en la práctica docente: Un estudio con maestros. Psicol. Educ. 2017, 23, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora Miranda, N.; Martínez-Otero Pérez, V.; Santander Trigo, S.; Gaeta González, M.L. Inteligencia emocional en la formación del profesorado de educación infantil y primaria. Perspect. Edu. 2022, 61, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, V.D. Competencia emocional en el profesorado de diferentes niveles educativos: Una revisión de la literatura. Investig. Valdizana 2022, 16, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V.G.; Suelves, D.M.; Méndez, C.G.; Mas, J.A.R.L. Future teachers facing the use of technology for inclusion: A view from the digital competence. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 9305–9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, M.P.; Ramos, M.; Berral, B. Las Tic Como Herramientas de Inclusión Educativa. Metodologías Activas con Recursos Metodológicos. Perspectivas y Enfoques Docentes; Avicam: Granada, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Reyes Rebollo, M.M.; El Homrani, M. TIC y discapacidad. Principales barreras para la formación del profesorado. EDMETIC Rev. Educ. Mediática Y TIC 2018, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Martín-Párraga, L. Formación del profesorado en la era digital. Nivel de innovación y uso de las TIC según el marco común de referencia de la competencia digital docente. Rev. Investig. Y Evaluación Educ. 2021, 8, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Batanero, J.M.; Sañudo, F.; Montenegro Rueda, M.; García Martínez, I. Physical Education Teachers and Their ICT Training Applied to Students with Disabilities. Case Spain. Sustain. 2019, 11, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Ruiz-Palmero, J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. Teachers’ digital competence to assist students with functional diversity: Identification of factors through logistic regression methods. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 53, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Batanero, J.M. TIC y Discapacidad: Investigación e Innovación Educativa; Octaedro: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Solas-Martínez, T.; Cáceres-Reche, M.P.; Romero-Rodríguez, J.J.; Ramos-Navas-Parejo, M. Estudio Bibliométrico de los documentos indexados en Scopus sobre la Formación del Profesorado en TIC que se relacionan con la Calidad Educativa. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2020, 23, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Batanero, J.M.; Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J. Are primary education teachers trained for the use of the technology with disabled students? Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2022, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Montes, C.D.P.; Caurcel Cara, M.J.; Rodríguez Fuentes, A.; Capperucci, D. Opinions, training and requirements regarding ICT of educators in Florence and Granada for students with functional diversity. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 23, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, E.L.; Cerero, J.F. Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación y diversidad funcional. Conocimiento y formación del profesorado en Navarra. IJERI Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. 2020; 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Arroyo, M.J. Las TIC al servicio de la inclusión educativa. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2014, 25, 108–126. [Google Scholar]

- González, I.; Macías, D. La formación permanente como herramienta para mejorar la intervención del maestro de educación física con alumnado con discapacidad (Lifelong learning as a tool to improve physical education teachers’ intervention with students with disabilities). Retos. Nuevas tendencias en Educación Física, Deportes y Recreación 2018, 33, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz, P.; De Haro, R. ¿Hacia dónde va la escuela inclusiva? Análisis y necesidades de cambio en centros educativos. In Acompañar la Inclusión Escolar; Moliner García, O., Ed.; Dykinson, S.L: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M.; Villagra, A.; Castejón, F.J. Coordination between physical education teachers and physical therapists in physical education classes: The case of the autonomous community of Madrid in Spain. Movimiento 2019, 25, e25015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascone, C.; de Cesare, G.R.; D’Elia, F. Physical education teacher training for disability. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Clegg, Z.; Conn, C.; Hutt, M.; Crick, T. Aspiring to include versus implicit ‘othering’: Teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education in wales. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2022, 49, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Olivencia, J.J.; López-Berlanga, M.C.; Espigares, A.M.; Lirola, F.V. Compulsory education teachers’ perceptions of resources, extracurricular ac-tivities and inclusive pedagogical training in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley 6/2014, de 25 de julio, Canaria de Educación no Universitaria. BOE nº 238, de 1 de octubre de 2014. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/medusa/edublog/ceipaguadulce/wp-content/uploads/sites/654/2014/08/ley-canaria-de-educacion-no-universitaria.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Decreto 25/2018, de 26 de febrero, por el que se regula la atención a la diversidad en el ámbito de las enseñanzas no universitarias de la Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias. Available online: https://www.cedid.es/es/documentacion/ver-legislacion-novedad/532207/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, N.M.; Ravitch, S.M. Interviews. In The SAGE Ency-Clopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation; Frey, B.B., Ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 872–876. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Marí, I.; Lacruz-Pérez, I.; Sanz-Cervera, P. Percepciones y actitudes del profesorado hacia el uso de la tecnología como una herramienta inclusiva. Reidocrea 2023, 12, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gavira, R.; Moriña, A.; Morgado, B. Challenges to inclusive education at the university: The perspective of students and disability support service staff. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 34, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F. La profesión docente en la perspectiva del siglo XXI: Modelos de acceso a la profesión, desarrollo profesional e interacciones. Rev. Educ. 2021, 393, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, J.; Garrido-Martos, R. Formación inicial y acceso a la profesión: Qué demandan los docentes. Rev. Educ. 2021, 393, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egido Gálvez, M.I. Los modelos médicos aplicados al profesorado: La propuesta del “MIR educativo” a la luz de las experiencias internacionales de iniciación a la profesión docente. Rev. Educ. 2021, 393, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrijos Fincias, P.; Martín Izard, J.F.; Rodríguez Conde, M.J. La educación emocional en la formación permanente del profesorado no universitario. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2018, 22, 57–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, L.; Ardeleanu, K. Work climate in early care and education and teachers’ stress: Indirect associations through emotion regulation. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 31, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, M.; Evans, I.; Jones, L.C. The effects of emotional awareness training on teachers’ ability to manage the emotions of preschool children: An experimental study. Escr. Psicol. 2016, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayón, A. Competencia emocional docente, ¡la (r)evolución interior! Rev. Padres Y Maest. 2015, 361, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.; GreenBerg, M. The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 1, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, A.; Sánchez, R.; Arigita, A. Formación emocional del profesorado y gestión del clima de su aula. Prax. Saber 2019, 10, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Prados, M.Á.; Penalva López, A.; Guerrero Romera, C. Profesorado y convivencia escolar: Necesidades formativas. Magister 2020, 32, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R.; Mateo, J. Competencias Emocionales Para un Cambio de Paradigma en Educación; Horsori Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- López-Goñi, I.; Goñi, J.M. La competencia emocional en los currículos de formación inicial de los docentes. Un estudio comparativo. Rev. Educ. 2012, 357, 467–489. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M.A. Learning to teach: Knowledge, competences and support in initial teacher education and in the early years of teaching. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sáenz, J.; Díez-Gómez, A.; Pérez-Albéniz, A.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Educación emocional en el futuro docente: Una asignatura pendiente. In Propuestas de Innovación Para el Desarrollo en Contextos Educativos; Universidad de La Rioja: La Rioja, Spain, 2023; pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- González Rivas, R.A.; Gastélum-Cuadras, G.; Velducea, W.; González Bustos, J.B.; Domínguez Esparza, S. Analysis of teaching experience in Physical Education classes during COVID-19 confinement in Mexico. Retos-Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2021, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.; Morán, L.; Gómez, L.; Solís, P.; Alcedo, M. Actitudes hacia las personas con discapacidad: Una revisión de la literatura. Rev. Española Discapac. 2022, 10, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubova, G.; Kellems, R.O.; Chen, B.B.; Cusworth, Z. Practitioners’ Attitudes and Perceptions Toward the Use of Augmented and Virtual Reality Technologies in the Education of Students with Disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2021, 37, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, V.; Gabarda, V.; Peirats, J. Formación y competencia digital del profesorado de Educación Secundaria en España. Texto Livre 2023, 16, e44851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, S.; El-Daou, B. The Relationship between Teachers’ Self-Efficacy, Attitudes towards ICT Usefulness and Students’ Science Performance in the Lebanese Inclusive Schools 2015. World J. Educ. Technol. Curr. Issues 2016, 8, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Llorente, A.; Sánchez-Gómez, M. Perceptions and Attitudes of Future Primary Education Teachers on Technology and Inclusive Education. J. Inf. Technol. Res. 2020, 13, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Questions |

|---|---|

| Training | What specific training have you received in relation to the care of SENS and SEN students? |

| Personal resources | What personal resources do you consider necessary to support SENS and SEN students in your classroom? |

| Material resources | What material resources do you use or consider necessary to support SENS and SEN students in your classroom? |

| Category | Subcategory | Description | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitisation Training for SENS and SEN Students | Understanding and appreciation of individual differences | Promote understanding and appreciation of the differences | SENSI |

| Theoretical basis | Concept and types of SENS and SEN | Definition and classification | FCCON |

| Legal and regulatory framework for attention to diversity | Regulation applicable to SENS and SEN students | FCNOR | |

| Model and approach for inclusive education | Sets of rules and procedures for responses | FCMOD | |

| Evolutionary development and characteristics of SENS and SEN students | Knowledge of evolutionary stages | FCCAR | |

| Curricular material adaptations | Material adapted to the needs of students with SENS and SEN | Adjustments and modifications made to the different elements of the curriculum to meet their needs | ACUMA |

| Intervention strategies | Teaching–learning intervention strategies for SENS and SEN care | Procedures implemented to achieve meaningful learning | EIEA |

| Strategies to promote student participation and autonomy | Procedures implemented to achieve meaningful learning | EPAR | |

| Inclusive practices | Design of activities and programs that promote student participation | Actions implemented to promote student access and participation in the different areas of the centre | PRADA |

| Creation of an inclusive school culture and acceptance of differences | Set of actions to generate values and beliefs that favour inclusion | PRACUL | |

| Collaboration | Teamwork with other professionals | Working with different professionals towards a common goal, exchanging knowledge and experience | COLEQU |

| Networking with the rest of the teachers in the school | Generate a space for cooperation to exchange information and achieve the objectives | COLRED | |

| Coordination with external support services | Establish relationships with agents outside the educational centre | COLSERV | |

| Emotional Education | To develop students’ emotional and social skills | To train students to establish healthy relationships and manage their emotions | EEHAB |

| Strategies for emotion management and conflict resolution | To train students to learn how to manage conflict situations in the centre or in other contexts | EEGES | |

| Creating emotionally safe and supportive classroom environments | Learning to manage the climate and the relationships established in the classroom | EESEG | |

| Family | Involve and collaborate with the families of SENS and SEN students | Learning to generate cooperative work with families | FAMCOL |

| Recognition of the family’s role in the educational process | To sensitise and make teachers aware of the role and importance of families in the school context | FAMPAPEL | |

| Strategy to encourage the active participation of families in education | Learn strategies to encourage family participation and involvement in the centre | FAMPAR | |

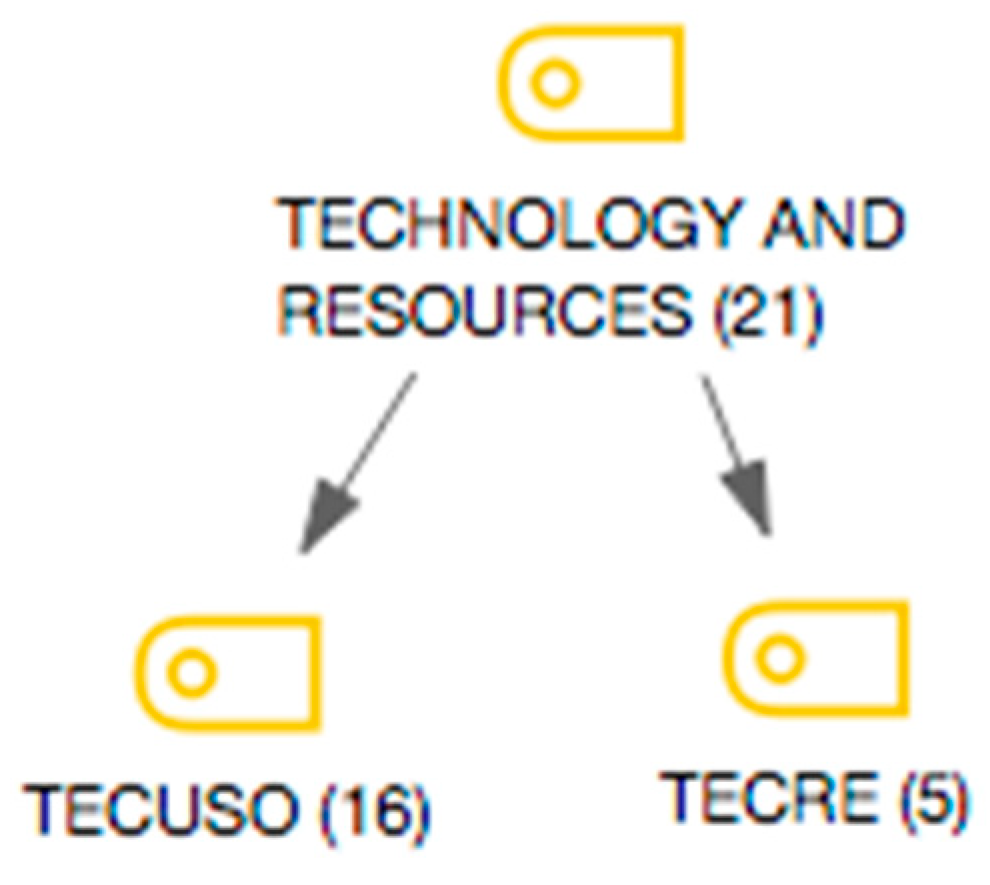

| Technology and resources | Use of technology and resources to support the education of SENS and SEN students | Learning how to use ICT tools to promote student learning | TECUSO |

| Specific resources depending on the type of SENS and SEN | To be aware of specific tools for each SENS and SEN | TECRE |

| Dimension | Category | Description | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal resources | LSE Interpreter | Professional who interprets simultaneously between spoken Spanish and Spanish Sign Language (LSE) to facilitate information access | ILSE |

| Communication mediator | Professional who supports deaf, deafblind and people with communication disorders in their interaction with the environment, to facilitate communication | MEDCOM | |

| Hearing and Language Teacher | Professionals who work with students to enhance their communicative and linguistic skills according to the school’s guidelines | ORI | |

| Teacher specialising in SENS | Involves developing a deep and empathetic understanding of the needs, challenges, and potential of these students, as well as promoting positive attitudes | MAESAL | |

| Counsellor | Professionals who are responsible for supporting students academically, socially and personally to help them thrive. They give advice to teachers who care for SENS and SEN students | PROFESNEAE | |

| Material Resources | Adapted didactic material | Materials adapted to the needs of students (Braille books, audiovisual resources, subtitles, etc.) | MATADP |

| Communication support | Augmented and alternative communication system to support communication (pictograms, communication boards, voice communication applications, LSE, shadow teacher) | RECACOM | |

| Technology | Technology that facilitates access and participation of SENS and SEN students in their educational process (accessibility applications, augmented or alternative communication devices or screen reading software) | TECNO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Jiménez, M.d.C.; Puerta-Araña, I.; González-Afonso, M.C. Qualitative Study to Identify the Training and Resource Needs of Secondary School Teachers in Responding to Students with SEN and SENS. Disabilities 2024, 4, 872-892. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040054

Rodríguez-Jiménez MdC, Puerta-Araña I, González-Afonso MC. Qualitative Study to Identify the Training and Resource Needs of Secondary School Teachers in Responding to Students with SEN and SENS. Disabilities. 2024; 4(4):872-892. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040054

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Jiménez, María del Carmen, Irene Puerta-Araña, and Miriam Catalina González-Afonso. 2024. "Qualitative Study to Identify the Training and Resource Needs of Secondary School Teachers in Responding to Students with SEN and SENS" Disabilities 4, no. 4: 872-892. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040054

APA StyleRodríguez-Jiménez, M. d. C., Puerta-Araña, I., & González-Afonso, M. C. (2024). Qualitative Study to Identify the Training and Resource Needs of Secondary School Teachers in Responding to Students with SEN and SENS. Disabilities, 4(4), 872-892. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4040054