Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Children and Adolescents with Disabilities: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

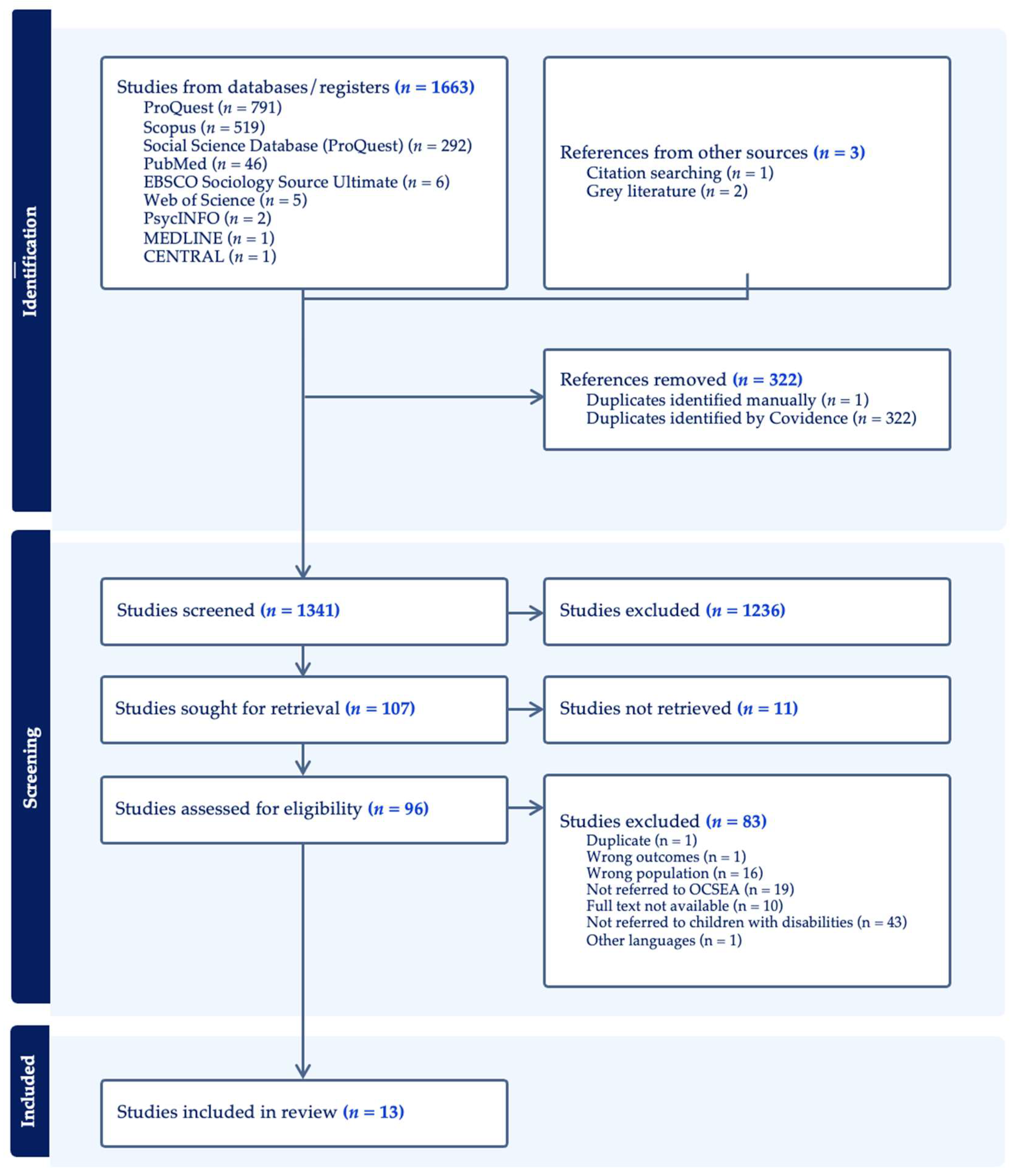

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence

3.1.1. Victim Age

3.1.2. Victim Gender

3.1.3. Types of Disabilities

3.2. Nature

3.2.1. Perpetrators’ Characteristics and Techniques Employed

3.2.2. Duration and Start of OCSEA

3.3. Associated Risk Factors

3.3.1. Lack of Parental Monitoring and Supervision of Online Activities

3.3.2. Consequences of OCSEA Experienced by the Victims

3.3.3. Vulnerabilities of the Victims

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Terms | |

|---|---|

| Context | “abuso sexual en línea” OR “explotación sexual en línea” OR “violencia sexual en línea” OR “explotación y abuso sexual en línea” OR “chantaje sexual en línea” OR “acoso sexual en línea” OR “crimen sexual en línea” OR “sextorsión en línea” OR “imágenes prohibidas” OR “transmisión en vivo” OR “engaño en línea” OR “coacción en línea” |

| Condition | discapacidad OR discapacidades OR “trastorno del espectro autista” OR autismo OR “discapacidad intelectual” OR “discapacidades de aprendizaje” OR discapacitado OR deterioro OR “discapacidad física” OR “discapacidad visual” OR “ciego” OR “sordo*” OR “pérdida auditiva” OR “enfermedad mental” OR “lesión cerebral” |

| Population | niñ* OR adolescen* OR infant* OR bebé OR bebés OR toddler* OR “persona joven*” OR “personas jóvenes” OR juventud OR teen* OR preteen* OR pre-teen* OR “preteen*” OR kid* OR prepub* OR pre-pub* OR “pre pub*” OR post-pub* OR postpub* OR “post pub*” OR pubescen* OR pubert* OR juvenil* OR menor* OR niño* OR niña* OR preescolar* |

| Title | Method Explained | Participants | Comparator | Outcomes: Type of OCSEA | Outcomes: Type of Disability | Outcomes: Measurement of Outcomes | Summary RoB Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online risk for people with intellectual disabilities [22] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Psychological Distress and Its Mediating Effect on Experiences of Online Risk [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Online Grooming as a Manipulative Social Interaction [20] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 3 |

| Making Sure Your Home Doesn’t Have an Open Door to Child Sexual Abusers [19] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 |

| Mapping Real-World to Online Vulnerability in Young People with Developmental Disorders: Illustrations from Autism and Williams Syndrome [17] | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Cibervíctimas con discapacidad: cuestiones victimológicas y retos forenses [21] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 |

| A global systematic scoping review of literature on the sexual exploitation of boys [24] | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| Cybervictimization of Young People with an Intellectual or Developmental Disability: Risks Specific to Sexual Solicitation [27] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Seeking Justice and Redress for Victim-Survivors of Image-Based Sexual Abuse [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 5 |

| Online Grooming: Factores de Riesgo y Modus Operandi a Partir de un Análisis de Sentencias Españolas [4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 5 |

| Mapping online child safety in Asia and the Pacific [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Youth Sexual Exploitation on the Internet: DSM-IV Diagnoses and Gender Differences in Co-occurring Mental Health Issues [13] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| The Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Deaf and Disabled Children Online [18] | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 |

References

- WHO. Global Status Report on Preventing Violence Against Children. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-ofhealth/violence-prevention/global-status-report-on-violence-againstchildren-2020 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Norman, R.E.; Byambaa, M.; De, R.; Butchart, A.; Scott, J.; Vos, T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Haykal, H.A.; Youssef, E.Y.M. Child Sexual Abuse and the Internet—A Systematic Review. Hu Arenas 2023, 6, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riberas-Gutiérrez, M.; Reneses, M.; Gómez-Dorado, A.; Serranos-Minguela, L.; Bueno-Guerra, N. Online Grooming: Factores de Riesgo y Modus Operandi a Partir de un Análisis de Sentencias Españolas. Anu. Psicol. Jurídic. 2023, 34, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N.; Powell, A. Technology-Facilitated Sexual Violence. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018, 19, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Açar, K.V. Organizational Aspect of the Global Fight against Online Child Sexual Abuse. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D.; Turner, H.; Colburn, D. Prevalence of Online Sexual Offenses Against Children in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2234471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WeProtect Global Alliance. Analysis of the Sexual Threats Children Face Online. Global Threat Assessment 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.weprotect.org/global-threat-assessment-23/analysis-sexual-threats-children-face-online/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Kloess, J.A.; Hamilton-Giachritsis, C.E.; Beech, A.R. Offense Processes of Online Sexual Grooming and Abuse of Children Via Internet Communication Platforms. Sex. Abus. 2019, 31, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Cerna-Turoff, I.; Zhang, C.; Lu, M.; Lachman, J.M.; Barlow, J. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: A multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Disability. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2008. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-1-purpose.html (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Klebanov, B.; Friedman-Hauser, G.; Lusky-Weisrose, E.; Katz, C. Sexual Abuse of Children with Disabilities: Key Lessons and Future Directions Based on a Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 25, 15248380231179122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.; Mitchell, K. Youth Sexual Exploitation on the Internet: DSM-IV Diagnoses and Gender Differences in Co-occurring Mental Health Issues. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2007, 24, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lough, E.; Flynn, E.; Riby, D.M. Mapping Real-World to Online Vulnerability in Young People with Developmental Disorders: Illustrations from Autism and Williams Syndrome. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WeProtect Alliance. The Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Deaf and Disabled Children Online. 2021. Available online: https://www.weprotect.org/wp-content/uploads/Intelligence-briefing-2021-The-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-of-disabled-children.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Internet Watch Foundation (IFW). Making Sure Your Home Doesn’t Have an Open Door to Child Sexual Abusers: A Guide for Parents and Carers. 2023. Available online: https://talk.iwf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/A-guide-for-parents-and-carers-v7.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Horskykh, M. Online Grooming as a Manipulative Social Interaction: Insights from Textual Analysis. Pol. J. Engl. Stud. 2018, 4, 79–111. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel, I.; Agustina, J.R. Ciber víctimas con discapacidad: Cuestiones victimológicas y retos forenses. Rev. Española Med. Leg. 2019, 45, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, D.D. Online risk for people with intellectual disabilities. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2019, 24, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asam, A.; Lane, R.; Katz, A. Psychological Distress and Its Mediating Effect on Experiences of Online Risk: The Case for Vulnerable Young People. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 772051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, C.; Smith, S.J.; Kim, K.; Hua, N.; Noronha, N.; Kavenagh, M.; Wekerle, C. A global systematic scoping review of literature on the sexual exploitation of boys. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 142, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackley, E.; McGlynn, C.; Johnson, K.; Henry, N.; Gavey, N.; Flynn, A.; Powell, A. Seeking Justice and Redress for Victim-Survivors of Image-Based Sexual Abuse. Fem. Leg. Stud. 2021, 29, 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.D. Mapping online child safety in Asia and the Pacific. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2018, 5, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, C.L.; Sallafranque-St-Louis, F. Cybervictimization of Young People with an Intellectual or Developmental Disability: Risks Specific to Sexual Solicitation. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 29, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, N.; Guilera, G.; Forns, M.; Gómez-Benito, J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, B.; Jiang, Y.; Song, Y.; Jin, Y. Knowledge, attitude and practice of child sexual abuse prevention among parents of children with hearing loss: A pilot study in Beijing and Hebei Province, China. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2019, 28, 781–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wissink, I.B.; Van Vugt, E.; Moonen, X.; Stams, G.J.J.; Hendriks, J. Sexual abuse involving children with an intellectual disability (ID): A narrative review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 36, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.; Stalker, K.; Franklin, A.; Fry, D.; Cameron, A.; Taylor, J. Enablers of help-seeking for deaf and disabled children and adolescents following abuse and barriers to protection: A qualitative study. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. National Plan of Action to Tackle Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in Kenya; Ministry of Public Service, Gender, Senior Citizens Affairs and Special Programmes State Department for Social Protection, Senior Citizens Affairs and Special Programmes Directorate of Children’s Services: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. Available online: https://www.nccs.go.ke/sites/default/files/resources/National-Plan-of-Action-to-Tackle-Online-Child-Sexual-Exploitation-and-Abuse-in-Kenya-2022-2026.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Finkelhor, D.; Turner, H.; Colburn, D. The prevalence of child sexual abuse with online sexual abuse added. Child Abus. Negl. 2024, 149, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Terms | |

|---|---|

| Context | “online sex* abus*” OR “online sex* exploit*” OR “online sex* viol*” OR “online sex* exploit* and abus*” OR “online sex* blackmail*” OR “online sex* harass*” OR “online sex* crim*” OR “online sextort*” OR “prohibited images” OR “live streaming” OR “online grooming” OR “online coercion” OR OCSE OR OCSA OR OCSEA |

| Condition | disability OR disabilities OR disab* OR “autism spectrum disorder” OR autism OR “intellectual disability” OR “learning disabilities” OR disabled OR impairment OR “physical disabilit*” OR “vision impairment” OR “blind” OR “deaf*” OR “hearing loss” OR “mental illness” OR “brain injury” |

| Population | child* OR adolescen* OR infant* OR baby OR babies OR toddler* OR “young person*” OR “young people” OR youth* OR teen* OR preteen* OR pre-teen* OR “preteen*” OR kid* OR prepub* OR pre-pub* OR “pre pub*” OR post-pub* OR postpub* OR “post pub*” OR pubescen* OR pubert* OR juvenile* OR underage* OR minor* OR boy* OR girl* OR preschool* |

| Study ID | Type of Study | Country/Region | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online risk for people with intellectual disabilities [22] | Literature review | Not applicable | Children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities |

| Psychological Distress and Its Mediating Effect on Experiences of Online Risk [23] | Quantitative study | England, United Kingdom | A population of 15,278 children and adolescents between 11- and 17 years old including disability |

| Online Grooming as a Manipulative Social Interaction [20] | Case study | Not specified | Adult victim with disability of online grooming when she was a child |

| Making Sure Your Home Doesn’t Have an Open Door to Child Sexual Abusers [19] | Report (Qualitative) | Not specified | Children and adolescents with disabilities |

| Mapping Real-World to Online Vulnerability in Young People with Developmental Disorders: Illustrations from Autism and Williams Syndrome [17] | Literature review | Not applicable | Children and adolescents with Autism and Williams Syndrome |

| Cibervíctimas con discapacidad: cuestiones victimológicas y retos forenses [21] | Editorial—review | Not applicable | Children and adolescents with disabilities |

| A global systematic scoping review of literature on the sexual exploitation of boys [24] | Systematic review | Not applicable | Children and adolescents (boys) with physical disabilities that experienced child sexual exploitation |

| Cybervictimization of Young People with an Intellectual or Developmental Disability: Risks Specific to Sexual Solicitation [27] | Literature Review | Not applicable | Children and adolescents with disabilities |

| Seeking Justice and Redress for Victim-Survivors of Image-Based Sexual Abuse [25] | Qualitative study | United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia | Children and adolescent victims of image-based sexual abuse |

| Online Grooming: Factores de Riesgo y Modus Operandi a Partir de un Análisis de Sentencias Españolas [4] | Quantitative study | Spain | A sample of 20 abusers and 65 victims of OCSEA Children and adolescents with and without disabilities |

| Mapping online child safety in Asia and the Pacific [26] | Literature review | Not applicable | Children and adolescents with disabilities |

| Youth Sexual Exploitation on the Internet: DSM-IV Diagnoses and Gender Differences in Co-occurring Mental Health Issues [13] | Quantitative study | Europe, America | A total of 512 youth and adolescents with disabilities receiving mental health services |

| The Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Deaf and Disabled Children Online [18] | Report (Quantitative) | Global | Children and adolescents with disabilities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Álvarez-Guerrero, G.; Fry, D.; Lu, M.; Gaitis, K.K. Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Children and Adolescents with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Disabilities 2024, 4, 264-276. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4020017

Álvarez-Guerrero G, Fry D, Lu M, Gaitis KK. Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Children and Adolescents with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Disabilities. 2024; 4(2):264-276. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4020017

Chicago/Turabian StyleÁlvarez-Guerrero, Garazi, Deborah Fry, Mengyao Lu, and Konstantinos Kosmas Gaitis. 2024. "Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Children and Adolescents with Disabilities: A Systematic Review" Disabilities 4, no. 2: 264-276. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4020017

APA StyleÁlvarez-Guerrero, G., Fry, D., Lu, M., & Gaitis, K. K. (2024). Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Children and Adolescents with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Disabilities, 4(2), 264-276. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities4020017