Abstract

People with acquired apraxia of speech (AOS) and aphasia commonly experience long-term communication disability without support for their ongoing recovery or self-management. Little is known about their lived experience of metalinguistic abilities and capacity to harness them for self-management of speech production. The author, a speech and language therapist (SLT), revisited her previous qualitative study after her own more recent lived experience of recovering from mild aphasia. Participant perspectives were explored from a longitudinal case series (eleven people with confirmed AOS and aphasia discharged from SLT), with full ethical approval. The anonymized data comprised detailed transcripts from videoed semi-structured interviews, participant assessments, field notes and reflections, member checking, and reflexivity. The original systematic thematic analysis of these data in NVivo software was re-interrogated by the author, deriving three overarching themes: Metalinguistic awareness of spoken communication breakdown, Self-management, and Therapeutic assessment. The participants conveyed the nature, occurrence, context, mechanism, and purpose underlying errors in spoken communication (themes of What, When, Where, How and Why). They generated compensatory strategies, elucidated via subthemes with quotations, verified contemporaneously by an original participant volunteer. The findings support the value of metalinguistic co-construction during in-depth assessments of communication disability, offering fresh avenues for long-term self-management in aphasia and AOS.

1. Introduction

Rephrasing the proverb, “If someone has a fish, they can eat for a day; if someone knows how to fish, they can eat for a lifetime”. The question is, would metalinguistic strategies offer this ‘know-how’ for speaking in people with acquired speech and language impairments? The author (K.M.), a speech and language therapist (SLT, used synonymously with ‘speech and language pathologist’), was prompted to revisit her previously unpublished qualitative study of apraxia of speech (AOS) and aphasia in the light of her own more recent lived experience of recovering from mild aphasia. Metalinguistic awareness emerged as a major theme from that study, and K.M.’s subsequent personal lived experience suggested potential for such awareness to underpin therapeutic self-management.

Metalanguage is a form of metacognition, in which the individual conveys awareness about language. Metalinguistic skills may include an individual’s capacity for awareness of their own language processes and capabilities, a conscious version of self-monitoring. Lived experience of metalanguage has not received systematic attention in relation to the communication disorders AOS and aphasia. There is a startling absence of information from this perspective, yet surely patient-centred care should begin there, requiring a phenomenological approach rather than a purely quantitative epistemology. Revisiting qualitative data analysis from K.M.’s doctoral work, this article focuses on how a case series of participants with AOS and aphasia construed their spoken communication over time. It explores whether metalanguage could offer an avenue for self-management in such cases (‘If someone knows how to fish…’).

To offer background, the nature of AOS and aphasia will first be summarized with a specific focus on spoken communication. Some of the literature about metalinguistic skills will be outlined in relation to aphasia and AOS, before setting the current study into the context of self-management for such a population, which is clinically desirable. Finally, additional background information from K.M.’s personal experience of aphasia will be offered, providing important context for evaluating the research.

1.1. Outlining Aphasia and AOS in Spoken Communication

Aphasia is a language disorder acquired following neurological change, which brings devastating consequences for communication. It occurs in about one-third of people following stroke, and may also result from traumatic brain injury, brain tumour, or other neurological disease including dementia [1,2]. Aphasia tends to impair language input and output processing (auditory comprehension, reading, spoken language, and writing or typing), although whilst considering multiple modalities, this article focuses mainly on spoken communication.

Due to their shared pathology, AOS may co-occur with aphasia and is generally regarded as a motor speech disorder, thought to reflect disordered motor programming, adversely affecting speech production [3]. In layman’s terms, in AOS speech sounds are made in a distorted way not attributable to muscle weakness or incoordination, or primary sensory loss. People with AOS ‘know what they want to say’ but they struggle to articulate it correctly. There has been controversy about the differential diagnosis of aphasia and AOS, not least because AOS rarely occurs in isolation [4]. Clinicians and researchers have continued to debate diagnostic criteria for AOS as distinct from aphasia [5] and to formulate and evaluate therapeutic insights [6]. In brief, one of the key points of contention has been differentiating between speech errors that arise from aphasia and those attributable to AOS. This distinction informs the selection of appropriate SLT techniques, with a separate body of evidence for treating each condition, although little mention of metalinguistic aspects [7,8].

Aphasic errors are deemed to reflect language processes underlying speech production, including substitutions of the wrong phoneme (speech sound), termed ‘phonemic paraphasia’. Aphasia may also involve issues at higher linguistic levels (a semantic error where the intended meaning is altered, as in ‘verbal paraphasias’; a grammatical error where the grammatical structure underlying the utterance is compromised, and so on) [9]. Apraxic errors, on the other hand, are deemed to represent a breakdown occurring after the form of the utterance has been planned, a phonetic–motoric disorder, with distorted articulation of speech sounds that may or may not result in the listener perceiving a different phoneme [4,10]. Clinically, the two types of error may co-occur in an individual, and most often co-exist in someone diagnosed with AOS (pure AOS is very rare). It is, therefore, both pragmatic and representative to examine metalinguistic insights from co-occurring impairments, rather than unequivocally teasing out the effects of AOS here [11]. (Metalinguistic strategies pertaining to aphasia alone are beyond the scope of this article.)

1.2. The Literature about Metalinguistic Skills in Aphasia and AOS

Metalinguistic skills in aphasia have yet to be systematically recognized as an avenue of therapeutic endeavour. The term has not featured in well-respected texts for cognitive neuropsychological approaches to aphasia therapy [12] or motor speech disorders [10], despite the knowledge that self-monitoring and compensation form a crucial part of recovery.

An assessment called MetAphAs has been perhaps the most comprehensive account of metalanguage in relation to aphasia [13]. It included multiple aspects of metalanguage within sections in a questionnaire asking people with aphasia if they could still use each aspect, or to demonstrate it. The work identified the potential for assessing metalinguistic strategies to understand an individual’s adaptive processes. The assessment, published four years after the completion of the current study, included (Section 1) inhibited, inner speech (silent reading), and deferred speech, which the authors termed aspects of ‘reflexivity’ to refer to the ability to separate the linguistic vehicle of communication from its functional use. Section 2 addressed the control of semiotic procedures in which non-verbal communication featured. Section 3 considered paraphrastic abilities, including an awareness of circumlocution and the tip-of-the tongue. Sections 4 (reported speech) and 5 (displaced use of language and theory of mind) had less direct potential for application in the current article. Section 6 (general monitoring and contextual cues) included awareness of syllables and prosody (phrasal stress). Thus, MetAphAs offers potential for addressing metalinguistic abilities in aphasia. The authors did not report whether this ‘preliminary approach’ was co-designed with people with aphasia [13] (p. 203). There are no reports of its application in apraxia of speech, which is worthy of consideration.

The aphasia literature contains scattered references to metalinguistic factors, including a single case report of metalinguistic loss in adolescent aphasia [14]. An increased understanding of ‘inner speech’ or ‘silent speech’ is particularly relevant for the current study. Single experimental case studies of aphasia without AOS offered neuropsychological models of the mechanisms underlying silent verbal rehearsal, representing faulty planning of the spoken (phonological) forms [15]. The subjective experience of inner (silent) speech in aphasia (without AOS) was confirmed experimentally to reflect successful lexical access in a study of 37 participants with aphasia [16]. A thematic analysis from the same participants revealed they had ‘some awareness of the mechanism or the level of the breakdown in their spoken output’ [17] (p. 6). An earlier thematic analysis of perspectives from eleven people with aphasia about their communication difficulties and strategies focused on their quality of life and conversational interactions rather than revealing metalinguistic factors [18].

When silent phonology tasks (e.g., rhyme judgements) form part of SLT assessment reports, they tend not to confer strategies for self-cueing speech production [19] (p. 133). A single case treatment entitled ‘autocue’ gave an elegant example of therapy for aphasia characterized by reading and naming deficits via patient-generated phonemic cues, along with multimodal approaches [20]. A similar therapy benefitted a person with aphasia and AOS [21] using self-generated phonemic cues and tactile placement to improve reading aloud and naming processes. Inner language is also recognized as another distinct phenomenon [22], with scope to be more fully integrated into current SLT practice. The evidence about metalanguage in AOS is even less prominent than in aphasia, found in error reduction approaches and studies using conscious self-monitoring [23,24,25].

In addition to single cases and experimental studies, accounts of the lived experience of aphasia may be a source of metalinguistic information. However, the sudden onset of acquired communication disorders tends to restrict how much information about compensatory strategies people with aphasia can volunteer without communication support. Accounts of lived experience tend to focus on holistic aspects of adjustment [26]. The exception may be progressive aphasias, where loss and adaptation are more gradual, offering scope to chart metalinguistic awareness as part of compensatory strategies in an individual [27].

Accounts of the lived experience of AOS are rare and tend to be non-academic, or not to examine metalinguistic awareness [28]. A longitudinal case study following traumatic brain injury showed metalinguistic insights into interactions between the speech accuracy and rate, factors underlying variability, and the experience of increased cognitive effort [29].

1.3. Self-Management for Long-Term Conditions

Self-management approaches address a person’s capacity to live well with their disability or condition by taking personal control and responsibility for it in a structured and supported way. Although amenable to treatment via SLT, it is widely accepted that many individuals will be ‘living with aphasia’ (or with AOS) and perceive speech as being an ongoing priority, as it is rare to experience full recovery [30,31]. Self-management is encouraged with people who have long-term conditions such as stroke. UK Guidelines state: ‘People with stroke should be supported and involved in a self-management approach to their rehabilitation goals’, although people with communication impairments are excluded when their communication or cognitive skills constitute a barrier [32] (p. 67). Metacognitive strategies are potentially valuable in people with aphasia for occupational aspects of rehabilitation [33]. The lack of self-management suitable for the needs of people with AOS and aphasia has been confirmed in a review finding no specific framework for aphasia self-management, proposing ‘that aphasia should have a dedicated self-management framework’ [34] (p. 936).

The absence of accounts that combine the lived experience of AOS and aphasia has contributed to the low profile of internalized mechanisms for ‘self-efficacy’, that is, improving one’s own speech and language disability. There was a recent call to revisit compensatory strategies in aphasia treatment [35], offering techniques suitable for long-term adoption. Such strategies include self-administered computerized practice, although without reference to metalanguage [34]. Compensatory approaches could equally be considered in relation to AOS but are relatively rare, such as self-administered computer therapy targeting whole word production with error reduction strategies [23].

In summary, there is a need for detailed accounts from people with aphasia and AOS about their speech production mechanisms, metalinguistic awareness, and strategies for the long-term self-management of their communication disabilities. This article addresses these issues from the perspective of people with lived experience.

1.4. Aims

The original research question was deliberately broad to allow participant perspectives to emerge as authentically as possible: What are the perceptions of people with apraxia of speech and aphasia about their spoken communication?

Returning to the analysis after a personal experience of aphasia, K.M. sought to address the following questions emerging from her reflections, recognizing that metalinguistic awareness had featured prominently in the original findings:

- (a)

- How did participants characterize their metalinguistic insights about their AOS and aphasia?

- (b)

- Did they attribute therapeutic relevance to their insights?

- (c)

- What are the implications for clinical practice?

1.5. Researcher Experience and Reflexivity

In the interests of methodological rigour, researcher perspectives will be outlined. K.M. chose to re-interrogate a previous qualitative data analysis of the experiences of AOS and aphasia, in which she acted as participant–observer, being an SLT clinician–researcher. Seven years after the completion of her doctoral work, she experienced mild aphasia in the context of viral encephalitis, giving an additional perspective from lived experience of aphasia and a renewed motivation to harness metalanguage therapeutically. Table 1 shows a vignette from K.M.’s experience, illustrating the degree to which she retained metalinguistic awareness even whilst experiencing aphasia, rather than focusing on the effects on cognition and mental health, because the metalinguistic aspects prompted this article. Participant L.D. reviewed a draft of this paper. In the vein of her previous role as a nurse, L.D. noted the mention of chronic fatigue and mental health in K.M.’s vignette. L.D. questioned firstly why that was not being developed in the article, and secondly whether the writing was cathartic. These aspects have not been included as K.M.’s story is outlined in more detail elsewhere [36] (chapter 4).

Table 1.

Researcher K.M.’s vignette about her personal experience of aphasia.

K.M.’s aphasia was not long-lived, lasting several months acutely. Eight years on, writing this article, she had residual issues with word-finding difficulties, sentence construction, and sustaining language use when tired (both orally and in writing). K.M. recognized that her awareness of errors in comprehension had been less self-evident than awareness of production errors (consistent with the vignette), as they may go un-noticed unless a communication partner signals frustration. K.M. noticed that when tired, multi-tasking, listening to complex language, or when a rapid interpretation was required, she sometimes misunderstood subtleties and benefitted from repetitions and longer consideration. She still experiences chronic fatigue, which occasionally escalates into ‘brain fog’ with wider cognitive impact. This represents a different picture from the participants in her doctoral research, which is acknowledged. In mitigation, this article focused on the original analysis of participants’ experiences (an inductive analysis) and focused retrospective insights within the results (deductive analysis). Making personal motivations transparent enhances credibility and rigour. K.M.’s motivation comes from a desire to translate the aspirations identified by participants to ‘help others’ through the findings, in therapeutic strategies and ultimately in their independent self-management of communication impairment.

2. Materials and Methods

The study adopted principles from Grounded Theory [37]. It aimed to explore what can be conveyed by people with AOS and aphasia following stroke about their speech production process, using multiple channels of communication (including drawing) to elucidate their insights (see Section 1.4). It formed part of K.M.’s doctoral research about AOS [4], but being a qualitative study, it was not included in the final thesis, which used parallel quantitative methodology. The qualitative data analysis included K.M.’s contemporaneous field notes and reflexivity, which have all been subject to further scrutiny in preparation for this article. Here, the deliberate focus will be on the awareness of errors in spoken production (as defined by individual participants) and of the factors influencing them, key themes arising from the investigation (inductive analysis). In addition, the recent deductive analysis from K.M. revisiting the original data set will be reported.

2.1. Ethical Considerations

Ethical permission for the study was granted for the entire doctoral study (UK Health Service: Main Research Ethics Committee: South Cheshire LREC No: CR100/01). The study used informed consent procedures suitable for processing by people with aphasia. Videos were transcribed in detail before being destroyed at the end of the project. Identifiers were removed from all written data, and only anonymized data (using pseudonym initials) were retained for future publication (except where participants had given express permission for excerpts to be shared in research or teaching). L.D.’s initials are her own, as she has chosen to be named in the publication (see acknowledgements).

2.2. Recruitment

The study used a diverse population as found in standard clinical practice in UK SLT. Indeed, therapeutic input should concern the perceptions of service users (in this case, people with AOS, most of whom also experience aphasia), so it may be argued that it would be unrepresentative to consider metalinguistic awareness of AOS in isolation. A convenience sample of eleven participants with aphasia and AOS recruited post-discharge from SLT for in-depth assessment excluded those with known progressive disease or dementia, dysarthria, moderate–severe hearing loss, or severe aphasia. This ensured that the participants would be able to complete the interviews and assessments. The participants were referred by their previous NHS (National Health Service) SLT services, within the northwest of England. The three women and eight men were monolingual English-speakers with a wide range of educational backgrounds and occupations, and they were at least 4 months post-stroke (mean 24.2 months; SD 26.9) (see participant demographics, Appendix A Table A1). Participant P.Y. withdrew from the study before completion due to deterioration in her health, and she was later diagnosed with progressive aphasia. Sadly, participant A.S. died prior to Interview 2 from co-morbidities.

All eleven participants also took part in a parallel program of assessment with quantitative findings. All participants’ aphasia was confirmed via in-depth assessments, and their clinical diagnosis of AOS was verified within a reliability study using clinical judgements of UK clinicians, [38], exhibiting diagnostic features consistent with AOS [39]. Table 2 shows a summary of AOS severity, with aphasia type and severity. Additional background information is shown in Appendix A Table A2 and Table A3, including some details from in-depth aphasia assessment. The reader is directed elsewhere to a more detailed exposition, including experimental studies manipulating linguistic variables in speech production and a sub-study establishing the reliability of error identification [4].

Table 2.

Summary of apraxia of speech (AOS) and oral apraxia severity levels (researcher findings), with aphasia types and severity levels (from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination [40]).

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

K.M. made home visits to gather information about participant perceptions of their spoken communication. Each participant completed the following:

- (1)

- An initial in-depth semi-structured video interview (Interview 1, see Section 2.4).

- (2)

- Multiple assessment visits in which they were encouraged to reflect, using neutral questions such as ‘How did that feel?’ ‘What happened there?’ K.M. also checked at the time that she had understood what the participant meant, using yes/no questions, gestures, and written cross-checking. The occurrence of a breakdown in spoken communication (errors of any kind) prompted extra commentary from them. The assessments used the sort of tests available in routine SLT practice.

- (3)

- Participation in experimental studies of repetition and reading, during which they were encouraged to volunteer comments.

The quantitative findings from (2) and (3) and formal aphasia testing may be found in a prior thesis [4], with excerpts shown in Table A2 and Table A3.

- (4)

- Agreeing a video clip from Interview 1 to share with other participants (see Section 2.5).

- (5)

- A second interview in response to viewing the compiled video clips (see Section 2.6).

- (6)

- A feedback session where the overall findings were shared (see Section 2.7).

The individual participants were videoed and transcribed (including non-verbal communication and diagrams) along with their commentary after the assessments and experimental studies (some off camera, gathered as field notes). Transcripts of Interview 1 and Interview 2 offered scope for comparison and cross-checking and were supplemented by the log of researcher reflections during the data collection, analysis, and participant feedback, all in the context of participant demographic information and assessment details. The participants were visited 7 to 12 times in all (spanning 7–15 months per person), with K.M. acting as participant–observer.

2.4. Interview 1

An initial semi-structured interview lasting about one hour was based on the deliberately open framework shown in Table 3, focusing on the basic question, ‘How do you communicate?’, to elicit wide-ranging experiences using supported conversation techniques well established in SLT [41,42]. (Participant L.D., in verifying this article, requested mention of the use of multiple methods of communication including ‘emojis’ due to aphasia severity.) The participants were also invited to complete a written version of the questions, to aid those who found it more difficult to communicate solely in a spoken interview. The initial prompt to share biographical information was important for establishing understanding and trust. K.M. approached all encounters with an attitude of listening and compassion, emphasizing that she offered assessment rather than therapy. As far as possible, participant experiences were prioritized rather than sharing clinical perspectives. In cases of ambiguity, K.M. repeated a simple summary of what the participant appeared to be saying for them to check, supplemented by written or pictorial versions where appropriate.

Table 3.

Interview framework for Interview 1.

2.5. Rationale for Selecting the Video Clips

Video clips from each initial interview were taken with the client’s consent, and compiled into a 30 minute video to be shown to each participant at the start of their second interview. (The video clips were also used for the purpose of the reliability study viewed by therapist raters, and included polysyllabic word production, used in the diagnosis of AOS [38].) Each clip used complete utterances and was around three minutes long to ensure the length of the compilation suited participants’ concentration spans. They were selected to allow comparison of common themes across cases, and in relation to K.M.’s research questions, sections where people talked about their apraxia (‘what was happening when their speech was difficult’) were prioritized. The tapes were interspliced with clips of gardens, an obvious contrast to the head and upper torso shots, to signal a time for relaxation and reflection. The participants did not help with selecting their clips because it was not practical within the time constraints, but they were asked if they were happy with the selection of their clip.

2.6. Interview 2 and Overall Analysis

Interview 2 took place at least 6 months after Interview 1. Participants viewed the video compilation at the start of the interview, and they were invited to comment during and afterwards. K.M. used general open questions about their views on communication to avoid leading the participants, but closed questions requiring a yes/no answer when checking that she had correctly understood what they said. (Some of the participants had also met each other since the initial interview through joint attendance at a local self-help group, so they may have gained additional insights from exchanges within that group that did not form part of the research.)

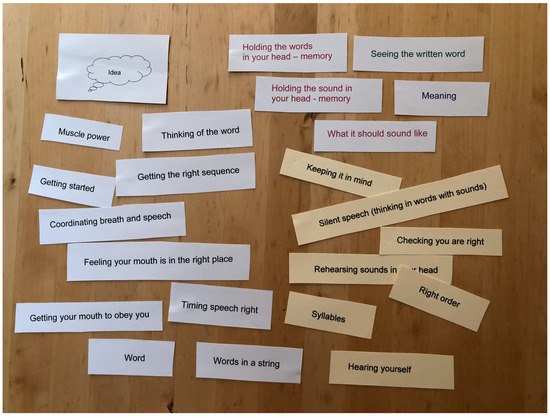

K.M. provided word cards that were based on vocabulary used by participants earlier in the study. The word cards provided anchors for the discussion about spoken production, as they were offered to each participant for comment or retrieved when that aspect was mentioned. Participants were able to group the words in a meaningful way to structure what they wanted to convey (with written words being less transitory than the spoken word). The word cards are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Word cards for supporting discussions exploring spoken communication.

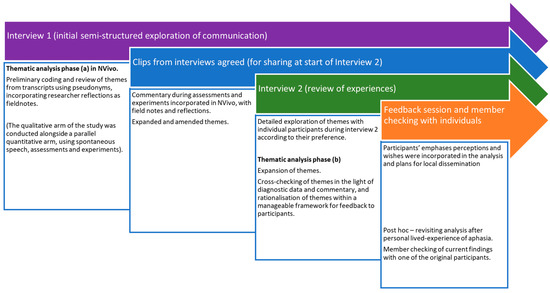

Thematic networks were used to analyse all participant data within NVivo software, giving primary importance to participant perceptions [43]. This is an established form of interpretive phenomenological analysis using constant comparisons to derive themes [37] (p. 101), which is suitable for people with aphasia [44]. The analysis proceeded in parallel with the data collection, allowing the participants to influence the course of the study. Figure 2 shows the data collection and analysis process over time.

Figure 2.

Data collection and analysis procedure.

2.7. Methodological Rigour

With the general aim of understanding peoples’ perceptions of their own AOS and aphasia, the initial interviews were deliberately wide in scope, allowing participant agendas to emerge via the semi-structured format. The video transcripts included non-verbal aspects of communication (gestures, facial expressions, pauses, and contrastive tones of voice), which helped capture communicative struggles and resolve any ambiguities. The participants were provided with copies of their interview transcripts set out simply, giving them an opportunity to check the reliability and add further comments (a form of member checking). Themes that emerged early on were developed further as the study progressed, adopting words used by the participants wherever possible (see Interview 2, for example), and it was stressed that each person’s experience was important in interpreting how they used the words. The longitudinal design enabled a shared narrative in the form of participants viewing the video compilation, and this facilitated participant reflexivity within Interview 2. It also stimulated cumulative insights over time. A final feedback session presented the main findings in a local voluntary aphasia group. Four of the participants took part and confirmed the dependability from their experience, putting together a leaflet to educate others.

The multiple data sources offered wide-ranging information about experiences of individuals, with opportunities for the triangulation of the findings [45], although it is not the intention here to integrate the qualitative and quantitative findings from differing epistemologies but rather to respect each methodology in combining them [46] (p. 51). K.M. revisited the original source data (transcriptions, field notes and reflections, and participant assessment findings) for verification in the light of her own lived experience of aphasia. However, K.M. has painstakingly checked that the findings reported here represent the participant voices within the original analysis, bearing in mind her own bias and deductive process (see Section 1.5). Although detailed member-checking of this latter process would have been desirable, it did not form part of the original design or ethical permissions, which determined that the participant feedback related to overall findings.

To improve the validity of this article, a draft was voluntarily verified for accuracy by one of the participants who had chosen to contact K.M. again more recently. L.D. was still living with moderate aphasia, though her use of automatized utterances meant that her AOS was now much less evident, 23 years after her brain haemorrhage. She was able to read sentences now, and agreed to review the draft in small sections, commenting on whether it was ‘true to life’, and suggesting any amendments.

3. Results (Thematic Analysis)

The data set provided a rich account of participant and researcher reflections on the breakdown in spoken expression from the perspective of the individual with communication disability. The thematic analysis will be reported to elucidate three overarching themes: Metalinguistic awareness of spoken communication breakdown, Self-management, and Therapeutic assessment.

3.1. Metalinguistic Awareness of Spoken Communication Breakdown

The overarching theme of ‘Metalinguistic awareness of spoken communication breakdown’ had main themes of ‘What’, ‘When’, ‘Where’, ‘How’, and ‘Why’. These are shown with subthemes and substantiated by participant quotations in Table 4. The order in Table 4 will be preserved in the discursive summary below.

Table 4.

Main themes and subthemes relating to breakdown in spoken production with excerpts.

3.1.1. Theme: What (Nature)

Participants sometimes noticed as they made an error, and they talked about the nature of it afterwards. The experience was described as a ‘struggle’ (A.S.), requiring effort, or the sound coming out in a distorted or an unintended way. The struggle was particularly evident when participants realized that they had said something wrong and made multiple successive attempts to correct it, not always successfully. Others pantomimed the actions they perceived to be occurring when an error happened, conveying an exaggeration of normal articulatory movements and facial expressions, and a series of different isolated sounds or groans coming out (B.G., C.E., L.D., R.G., M.L.).

Additionally, some errors were based on an inability to name something in the first place (word-finding difficulty), as B.J. experienced when shopping, shown in Table 4. Some participants noticed a ‘mistake’ even when there was no noticeable struggle, especially when it altered the meaning.

Participants talked of a ‘blockage’ preventing them from speaking, or a ‘blank’ when they tried to access the specifics required to communicate their intentions. The participants who referred to a ‘blank’ (e.g., L.D., M.L.) or ‘nothing at all’ (B.S.) tended to be experiencing more severe aphasia, and showed clear semantic deficits in assessment.

Many recognized the negative effect of speaking quickly or too loudly.

Frustration was widespread, sometimes leading to expressions of it being ’hopeless’ or ‘a mess’, so K.M. maintained positive feedback and encouragement. Even those who felt they were coming to terms with their communication disability noticed ongoing frustration:

- L.D.:

- I’m accept it now … erm (-) but impatient (slaps table)

There were accounts of negative reactions to spoken errors from other people who didn’t understand about aphasia or AOS, who assumed intellectual impairment, and the participant was unable to explain when being called ‘thick’, for example:

- C.E.:

- he’s a bit thick (circular gesture on side of head) … and that was bad … and that … and I-I-I didn’ like that … but you see I couldn’t … I couldn’t say … and that was that … and that was hard

Common ground was greatly valued by the participants, who were extremely excited to see others in the video compilation who they perceived had similar experiences of communication disability to themselves.

3.1.2. Theme: When (Occurrence)

Participants were searching for a pattern to their speech errors, often expressing that they did not know, before offering details. They attributed some association with their mood, diurnal variations, or hormonal changes. Sometimes it would just be a ‘bad day’ and the next one would be better. Being ‘excited’ or ‘angry’ made things worse, and laughter was an important release, as was swearing for some. Laughter and crying sometimes went hand in hand:

- L.D.:

- but er (-) (sighs) a wife and a husband (-) a crying (-) and laughing as well (gestures hands clasped) … erm (-) indignity ‘o things

Social contexts or stressful situations gave difficulties. Some participants linked errors to fatigue but others did not, or drew a distinction between general tiredness and communication fatigue (B.G.).

It is beyond the scope of this article to comment on the exact relationship between individual participant perceptions and their assessment findings. Nevertheless, within the in-depth assessments (see Section 2.3, items 2 and 3), repetition and reading phrases aloud were compared. This confirmed that in general the ‘modality’ affected the ease of spoken production, with some finding repetition easier than reading aloud, and others realizing the opposite was happening (as might be expected from different types of aphasia [4] (p. 287). B.G., for example, felt that reading aloud was easier because repetition taxed his memory while speaking, but the words remained on the screen, giving him extra information.

All participants shared the ongoing trauma of not knowing when problems would occur. Despite searching for patterns to errors, they had a frustrating unpredictability.

3.1.3. Theme: Where (Context)

Participants associated their errors with the context of what was being said. They could distinguish different levels of breakdown in the speech production process, especially those with mild aphasia. Long (multisyllabic) words were perceived as causing the most speech errors, with short words (fewer syllables) perceived as being easier, requiring less sequencing. Sentence length was also a recognized as a factor.

During the assessments, the participants additionally commented on the ease with which they could say certain target words or phrases, confirming that length tended to be problematic, coupled with how common or automatic (how ‘new’) the word was (frequency).

Some participants recognized errors related to their limited word choices in spontaneous speech, making it difficult to explain to a stranger when attempting communication.

- B.G.:

- I can only er (-) (sighs) say certain words and er (-) er … slow-slowly (indicating communication card explaining his difficulties) and this one a (.) godsend to me

There was often difficulty initiating utterances or individual words. Some participants recognized that difficulty initiating an utterance, although others (M.L., for example) initiated speech immediately but in a brief, error-ful way.

In their search for patterns to the errors, the participants wondered whether they were sound-specific or related to the order of sounds but with puzzling inconsistency.

Over the course of the study, the participants became more aware of factors such as the grammar of language. Many conveyed during the in-depth assessments that word class was influencing spoken communication, with verbs being harder than nouns. A.S. offered his own explanation, involving verb abstractness, which also had an impact on spontaneous speech:

- A.S.:

- when it’s, it’s, it’s er a nay er (-) a verb … it’s (gestures palms moving apart), it’s um … it isn’t as simple (-) as a noun … with the with the noun … it’s very positive what it is … but with the vo-verb it’s the … the sense (-) can be conveyed not so easily

The increased awareness of errors as the study progressed was sometimes painful for participants:

- B.S.:

- I don’t do this … because I ca-can’t do it any more … I could read when I was a kid … but now it can’t … I don’t seem to be very good today (-) ‘cause I can’t make that … I don’t kno-know at all

K.M. was careful to encourage and support them by affirming their ongoing skills and successes, and the value of harnessing their awareness.

3.1.4. Theme: How (Mechanism)

Participants gave a detailed account of what was happening when they were unable to say something, as illustrated by B.S.

- B.S.:

- the only thing I can say is that … that I in here (-) knows what it is (points to both sides of head) but (-) when I have to take this (point to back of head) … if er whatever it is … a-a-a-and (-) go here to here (points form head to mouth) … I cannot … there is nothing … there’s something either er … it, it doesn’t go any anywhere (opens hands) … or … it’s er i-it is something which erm I say to myself that ‘you know … what this is’ (points into mouth) (-) but you can’t tell it (points out of mouth)

Some of the issues concerned limited processing resources (including working memory) and a precarious sense of losing the plan before it could be said, accelerating in consequence. Sometimes participants used ‘memory’ to refer to the lexicon rather than working memory or short-term memory, so K.M. double-checked the meaning in each case. Participants showed awareness of syllable structure, with multisyllabic words presenting a greater challenge.

Internal speech, the degree to which they could ‘hear the words in their head’ while preparing to speak, varied widely. Some participants (e.g., B.S.) were conscious that skill was gone; others (e.g., J.R., D.R.) felt it was a partial ability. L.D. described her perseveration on a word (when unable to switch from repeating a previous word to saying a new one). She said the previous word was ‘echoing round’, preventing the switch. The final feedback group linked difficulties with silent speech to worsening errors in the presence of background noise.

Some participants recognized that their sensory feedback was important but variable. Their sensory feedback and additional oral apraxia may have improved since they first had their stroke (alongside an element of facial weakness for some, including B.J., L.D., and R.G.).

The participants ranged in their ability to imagine visual representations of words (internal blackboard). R.G. and B.J. both described how imagining the written words helped them say a phrase when they no longer had the words in front of them.

A detailed account of J.R.’s perceptions follows, to illustrate the richness of individual accounts of ‘How’, which sometimes spontaneously ventured into beneficial strategies that are considered within ‘Why’. This shows the nature of the interactions with K.M. taken in the context of the assessment and verified in Interview 2.

J.R. gave a summary of the nature of errors:

- K.M.:

- so (-) can you describe to me what’s happening? when when it’s difficult?

- J.R.:

- ooh erm … it ‘ere (points to left side of head) … it not com(.)ing (--) out (points to mouth)

- K.M.:

- yes

- J.R.:

- yeah

- K.M.:

- you got it in your head

- J.R.:

- yeah … a but i’ it won’t (-) (significant effort) come

She experienced some breakdown in the ability to select and sequence both the target words and the target sounds before saying them, but her main frustration was that even when she could do so, the sounds required a monumental struggle to produce:

- J.R.:

- everything (-) in there (points to side of head)

- K.M.:

- even the sounds

- J.R.:

- yes

- K.M.:

- but when you come to say it

- J.R.:

- it won’t come out (gestures from mouth rhythmically 3 times)

She also related how she could hold the sounds for the words in her memory during repetition but that they were not connected with the word meanings in that task, and that there was ‘noise’ on the system, like ‘magpies’ chattering in her head, as checked by K.M.:

- K.M.:

- when you said to me before that you’d got magpies in your head

- J.R.:

- yes

- K.M.:

- is that

- J.R.:

- yes

- K.M.:

- echoing round?

- J.R.:

- yes, yes

- K.M.:

- and it’s

- J.R.:

- and I’m trying to (points with both fingers to sides of head) … you know get you to ‘tame’ (circular repeated gesture forwards with left hand) … trying to get (.) the (.) same difference

- K.M.:

- mm (nods) yes

- J.R.:

- because otherwise it won’t come

- K.M.:

- when you’re saying in unison with me …we’re both talking at the same time

- J.R.:

- yes

- K.M.:

- you’re fine aren’t you

- J.R.:

- yes

- K.M.:

- it’s where you have to keep it in your head

- J.R.:

- (points to her head) yes

- K.M.:

- and then say it

- J.R.:

- yes, yes

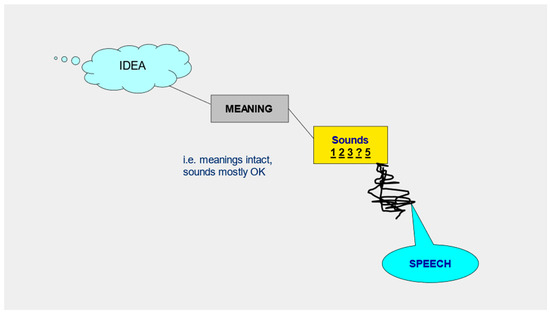

Figure 3 is a diagrammatic representation of what J.R. drew with K.M. as she contributed during Interview 2, using the word cards.

Figure 3.

An example of a diagrammatic representation of spoken communication (from J.R. in Interview 2).

Reading aloud required more concentration and time than repetition, as sometimes she perceived a mismatch between what she gleaned from reading and what was in her head (internal speech): “It not not real”. For her, internal speech was linked with her impaired auditory processing of what she heard:

- J.R.:

- ye-ye-ye-yes (points to side of head, then both sides) … because no-not (-) it (-) really listening in here … ‘come on’

Nevertheless, J.R. felt that reading was a helpful strategy to improve her speech but one that still required therapeutic support.

3.1.5. Theme: Why (Purpose)

Finding a reason for the errors was important to the participants:

- J.R.:

- but why is it the coming out? (points out of mouth)

They offered their own views, which were wide-ranging, including physical explanations. Some participants were wrestling with what was happening neurologically to change their communication, even feeling that they were infantile:

- L.D.:

- I can’t speak anyway (hand across chest)(-) but um (gestures left hand … across) a baby … but um (-) every day mmmm (looks deliberately from left to right and back) … what’s going on (-) inside of a mind (left hand towards left side of head)

Some (including M.L.) attributed the impairment to a missing link in their processing.

All participants reflected on why it was sometimes better and the strategies they identified, such as the benefit of relaxing and calming down or restarting rather than persisting with a troublesome utterance (L.D.). Beneficial calm happened more often with people who knew and understood. One helpful strategy was to slow down (which required conscious effort and concentration).

Some participants consciously substituted another utterance for their original one, to avoid making errors. D.R. recognized that some errors were associated with word finding choices, and that choosing ‘easier’ words reduced the errors:

- D.R.:

- er because (-) er (-) because I will go to one two three different words that I might be taking … and in the end (-) I can’t (-) worked out how to do this … and so (-) I’ll go (-) you know one those three (-) … go to the one I need … that I can get

C.E. gave detailed explanations of a strategy that helped him. He perceived he had the word in his head but could only pronounce it when first writing it down (see Table 4, subtheme ‘writing cue’) and then reading it aloud to assist his speech production (although even then he recognized his reading was not always accurate).

He also recognized that his spelling was inaccurate, further hampering the process but not preventing it:

- C.E.:

- I know the words … mm … I went … I’m talking about writing wrong … that … the word is wrong

- K.M.:

- so your spellings

- C.E.:

- that’s right … and sometimes … that was all right … that was all right … but it’s, it’s the middle

- K.M.:

- so when you spell a word … the beginning and the end are OK

- C.E.:

- yeah

- K.M.:

- but the middle is where it’s likely to go wrong

- C.E.:

- yeah

R.G., who had less severe aphasia, found that he could imagine the written words and that would be enough to reduce errors. J.R. related that the accuracy of her speech initiation was improved by first tracing on her hand what she believed to be the first letter of the word.

Advance preparation for a specific situation was helpful, as recognized by B.J. when he thought about supplementing spoken communication with drawing, which would reduce the pressure on his speech. Practice was perceived to be important for spoken communication, although those who lived alone (B.S., B.G., M.L., R.G.) had limited opportunities for talking. The reactions of other people had an important influence, and the participants all wanted ‘other people’ to be better informed about communication disabilities, including medical staff, who they perceived to lack insight. They wanted their experiences to help others.

‘Why’ was also construed in terms of whose fault it was. Blame was sometimes laid on others who did not understand, or the difficulties of the situation. However, often the participants expressed self-blame (see R.G., ‘my fault’, in ‘How’). Self-blame was coupled with a sense of powerless due to the loss of control, unpredictability, and isolation of the communication disability. Exploring the specifics of the mechanism behind spoken communication was inherently motivating. As the exploration was shared, the participants felt valued and the discoveries about spoken production, augmented by the sense of common ground, were a source of power and catharsis for them.

- R.G.:

- it’s as same(-) having someone (-) who knows wh-what they go, you going through

- B.S.:

- I looked (-) out a different person

- K.M.:

- when you see yourself

- B.S.:

- was me … yeah … it was me … but this other person there (-) he’s n-that isn’t me … but the … I-I felt (laughs) I felt (sighs) … I-s er-tr (-) well I-s er-ss … was (-) not (-) not ill

3.2. Self Management

The overarching theme of Self-management arose deductively from K.M.’s reflection on her ongoing clinical experience and her lived experience of retained metalanguage during mild aphasia, which she harnessed to manage her own communication impairment. Nevertheless, it was evident within the original analysis, particularly within the theme of ‘Why’, where the participants referred to aspects of metalanguage that they used to improve spoken communication (now redefined as ‘strategies for self-management of AOS and aphasia’ in Table 4.) Applying such strategies gave some self-management of their communication after their therapy had finished.

In revisiting the thematic analysis, the aspects below were also salient.

3.2.1. Metalinguistic Awareness at Multiple Levels

The participants wanted to explore various levels of underlying mechanisms (‘How’) but did not spontaneously make a distinction between language issues (aphasia) and motor speech issues (such as AOS), or between phonological paraphasia and semantic paraphasia. Although such distinctions may be important diagnostically, the ‘insider’ view was of a more seamless activity, where there was interaction between ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ processes, and they were unable to access the detail of the translation into production once they had selected the intended sounds.

The detailed experiences within the theme of ‘Where’ identified a range of levels of spoken breakdown in addition to the effects of their mood, context, modality, and variability, subthemes of ‘When’. These different levels were integrated in participant reflections about the underlying mechanisms (‘How’) and strategies for maximizing them (‘Why’). The detailed awareness in participants gave weight to the use of metalanguage in self-management.

3.2.2. Processing Load

Metalinguistic strategies differed from person to person, and the range of aphasia and AOS in the sample was extensive, although there was consensus about the experience of ‘load’. Where one aspect of spoken communication gave an excessive processing load, the whole utterance was derailed. This meant that their motor speech production was impacted by language processes (and vice versa). Participants perceived an interplay between aphasia and AOS during speech production. In describing the nature of errors (in ‘What’), participants equated a ‘mistake’ with a breakdown at any level, with concomitant frustration, loss of control, and failure to convey the intended message. Within the theme of ‘How’, participants demonstrated an awareness of a combination of factors contributing to the derailment of the intended utterance.

3.2.3. Empowerment

The variability and unpredictability of AOS and aphasia for the participants constituted a daily encounter with the unknown and the uncontrollable (see ‘When’—variability). They could sometimes predict when communication would break down, although not always, and the sense of ‘failure’ when errors occurred (see ‘Why’—‘blame’, ‘powerlessness’) was matched by a desire to take back control over communication now the SLT had ended.

The initial sharing of stroke narratives (Interview 1) recognized the profound trauma for participants, some of whom had experienced a total loss of communication, and all of whom continued to live with a communication disability even years afterwards. Met with researcher empathy and respect, this sharing enabled a privileged relationship of trust with participants who were still vulnerable. (Themes concerning post-traumatic adjustment in aphasia were not included here but have been explored elsewhere [36,44,47].) In this context, participant insights were encouraged and valued, and their own terms of reference were adopted. There was empowerment in the ownership of beneficial strategies (‘Why’ communication improves; “What makes it better?” in the original Interview 1 questions). Identification with other participants’ accounts (‘What’—’common ground’) was matched by a desire to educate others more widely about how to help (‘Why’—’other people’) move away from powerlessness. They voiced an enthusiasm for identifying shared ground with other participants and for using the findings in rehabilitation in general (as a means of recognizing their own contribution, giving value to their struggle, and helping others in the future). Empowerment may constitute a driver for promoting self-efficacy and self-management, with consequences for personal identity and living with a long-term condition [44].

3.3. Therapeutic Assessment

Participants welcomed in-depth assessment to understand their communication disorders better, enabling them to feel more in control, to ‘fail well’. Although K.M. repeatedly reminded the participants that she was not offering therapy, the assessment process turned out to be therapeutic (perhaps unsurprisingly, due to the influence of K.M.’s shared core value of helping people). This was evidenced in the participants’ enthusiasm for repeated assessment visits and the development of their depth of metalinguistic skills, with interview 2 providing very rich accounts compared with Interview 1. They also recognized the change in themselves (see B.S.’s quotation at the end of Section 3.1).

Participants identified mechanisms that had potential for being encouraged and harnessed (see ‘How’ and the discussion in Section 3.2). The dialogue revealed resources within participants that they may not otherwise have taken seriously or applied. For example, R.G.’s responses in the written form of the initial interview questions showed that whilst able to identify what made communication worse, he was less able to apply his insights in the form of strategies for helping communication. This gap showed the need for therapeutic support during assessments to promote application in everyday life.

The stance of K.M. in the interactions valued metalinguistic co-construction without imposing clinical theoretical frameworks. This was equivalent to a specific intention to offer therapy with a client, rather than therapy to a client.

4. Discussion

Overall, the case series confirmed that people with aphasia and AOS have metalinguistic awareness. This can be sophisticated even without prior training about linguistics or cognitive processing (shown by the varied backgrounds of the participants). Their awareness developed over the course of the study. They welcomed the use of key words in Interview 2 to help them confirm and qualify what they were experiencing, and they could consider each one in turn as to personal relevance, allowing detailed reflections about their speech production mechanisms. Clinical experience sees clients asking for SLT to help with ‘speech’ as their key priority (rather than for help with understanding even when that is also impaired), as reflected here and elsewhere [30].

Although compensatory mechanisms in the form of gestures and AAC did feature in the thematic analysis, the most highly developed themes were around spoken communication, the direction in which the research travelled in response to researcher and participant emphases. This may reflect the impact of AOS, and a different sample would be needed to explore the life experiences of others with aphasia (and no AOS) in more depth. This study leaves open questions about metalinguistic strategies beyond spoken production and the perceptions of people without AOS, both worthy of further investigation.

The sample of people with aphasia was heterogeneous, and they had different degrees of AOS and diverse experiences. Rather than preventing conclusions from being drawn, this offered the opportunity for exploring commonalities and exceptions and to derive implications for SLT clinical practice, where such populations are encountered. Moreover, it is likely that the metalinguistic awareness differs in form and degree according to individual ‘brain wiring’, reflecting pre-established neuropsychological correlates as well as the pathology. K.M.’s own preserved metalinguistic insights during aphasia (and without AOS) reflected a highly trained and developed awareness of such issues in a therapeutic role. Not everyone will offer (or indeed need) such specific insights, and one size does not fit all. Rather than being reductionist about metalinguistic strategies, this analysis offers a breadth of possibility and the scope for therapists and others to focus on person-specific strategies (transferability). Where there is commonality in abilities, value may come both from pre-established techniques and in the sense of solidarity with others, as identified by the participants within the subtheme of ‘common ground’.

4.1. Clinical Applications

The participants experienced a breakdown in spoken communication across a whole range of different linguistic levels (see Section 3.2.1), and the co-constructed accounts used vocabulary chosen by them (see Section 2.6 for example). A clinical classification would align such themes with linguistic levels and cognitive neuropsychological models (length and sounds (phonetic/phonological); frequency (frequency and automaticity of lexical items and connected speech); grammar (word class and syntax)). Within ‘What’, the theme of ‘word finding’ relates to lexical semantics and phonology. As already mentioned, it is not the intention in this paper to make detailed connections between individuals’ assessment findings and their perceptions (see Section 3.1.2) but rather to focus on the value of participant perceptions. Nevertheless, respecting perceptions from lived experiences may complement measurements from impairment-based assessments, and the two epistemological approaches may co-exist in clinical practice where controlled experimentation is neither possible nor intended.

Adopting a metaphor from K.M.’s clinical work may offer an accessible overview of the findings: the analogy of ‘roadworks’ for the damaged language network underlying the communication impairment. Applying the current findings, the themes ‘What’ and ‘When’ could be represented by the roadworks. In those terms, strategies for going round the ‘blockage’ were as important as impairment-based therapy to address the damage, particularly after the recovery plateaued. ‘Going round’ the damage might first require an awareness of the location of the roadworks (‘Where’), then the existing language or road network (‘How’), featured as the focus of co-constructed reflections shared in the context of assessment sessions. A diversion from the original route for spoken communication might evolve naturally or require specific support for adopting the strategies identified (see ‘Why’). Being strategies, such diversions would have scope for generalization beyond direct therapy. Finally, in coming to terms with the wider issues of causation and blame (shown in ‘Why’) during the shared reflections, clients might be offered affirmation and support towards empowered acceptance of their communication impairment.

Participants did not distinguish between purely ‘apraxic’ errors and ‘aphasic’ errors, although simply talked of things “going wrong”. This perception resonates with Miller’s early reference to ‘heterarchical’ (rather than sequential, hierarchical) models of speech production [48] (p. 144). It follows that there is potential for multiple causes of what is perceived as an error in speech output, or ‘derailment’, of spoken production. These concepts of the ‘processing load’ and ‘derailment’ may be especially pertinent in view of the current knowledge of extra-linguistic cognitive problems and stress impacting communication in aphasia [49,50,51]. These observations may give weight to the notion of approaching the two disorders concurrently within clinical practice.

Strategies for managing ‘load’ offered a meaningful avenue for exploration (see Section 3.2.2). For example, an awareness of where a breakdown is likely to occur again enables the person with communication impairment to adapt their communication in advance to avoid it and to apply strategies in novel situations. Specifically based on the findings, strategies for consideration might concern reducing the following aspects:

- (A)

- Linguistic load—choosing to use short words, slow rate, selecting frequent and concrete word forms, and simple grammar.

- (B)

- Cognitive load—reducing the competing demands on memory and attention; making use of additional modalities such as reading to enhance production; and enabling practice towards automaticity.

- (C)

- Environmental stress—through ‘calming’ and relaxation; reducing tiredness and fatigue; and educating ‘other people’ to respond well.

Participants’ self-blame for why they ‘went wrong’ and what they ‘should’ or ‘ought’ to have done, could lead to low mood and hopelessness. Strategies for mitigating errors helped reduce the sense of failure. Given that ‘perfect speech’ was not an option for the participants, knowledge about the underlying mechanisms was important for accepting the situation and ‘failing well’. In addition to self-forgiveness [44], being able to apportion blame to something tangible can avoid focusing on regret. It is known that people with aphasia often experience anxiety and depression [52], so empowerment from metalinguistic strategies may be valuable for mental health in those experiencing not only aphasia but also AOS.

4.2. Rigour and Limitations

The original study was conducted with an awareness of the importance of the professional role in the qualitative data collection, and its likely impact on the type of information and reflections offered by the participants [53]; the author’s subsequent lived experience of aphasia has been outlined as an important additional context affecting the emphases in this paper. The methodology adopted by K.M. as participant–observer with the case series was strengthened by member checking, and ultimately an acknowledgement that internal processing is just that. Reflecting on one’s own speech production process and understanding the reflections of others experiencing a communication breakdown is necessarily subjective, although it can also complement a body of knowledge from cognitive neuropsychology and neuroscience about what can be expected from the inner workings of the mind [54]. K.M. inevitably imparted some of that background knowledge to the participants, although repeatedly centralized the search for a common language for them to express their own perceptions rather than imposing such models on the interactions. The dependability of the themes is shown by the extensive quotations. The co-construction of insights about metalanguage is consistent with the views of people with communication impairments about the therapeutic relationship, and particularly the value of being ‘heard’ [55].

K.M.’s doctoral thesis focused on an investigation of AOS and grammar in connected speech following stroke, although the qualitative study generated broader perspectives from the same participants, being keen to better understand their communication impairments. The themes arose longitudinally as detailed assessments were explored, so the emergent focus on communication breakdown may derive from expectations of therapeutic support from K.M., despite her assertions that she was not offering ‘therapy’. Nevertheless, findings were generated beyond K.M.’s expectations, indicating that the participants’ perspectives were being respected. In designing the study, K.M. was expecting the participants to differentiate apraxic errors from aphasic ones (see Section 1.1). That was not what emerged. Even in instances where the participants had just noticed an error which appeared apraxic to K.M. from a diagnostic perspective, their accounts of what happened often included references to inner language and cognition, not just the difficulty in translation into spoken articulation. This consensus about processing load influencing errors seemed a significant revelation which required K.M. to adjust her stance and warranted further research. Additionally, the influence of ‘silent speech’ on errors in people with AOS, perceived to be exacerbated by background noise, was a new discovery for K.M., emerging from the co-constructive paradigm and offering a potentially useful therapeutic avenue. J.R.’s ‘partial’ or variable ability with ‘silent speech’ was also a valuable insight, which merits consideration when interpreting experimental findings elsewhere.

The focus on lived experience left some unanswered questions about how to apply metalinguistic strategies as part of SLT interventions, although participants did volunteer their own views on what helped (‘Why’). K.M.’s own clinical experience of the benefit of such activities was anecdotal and reflective, such as in Section 4.1, not forming part of the inductive analysis. Although the participants did identify helpful metalinguistic strategies, they realized they did not make full use of them in normal interactions or everyday life (B.J., R.G.), and that adoption was an additional challenge (which C.E. assiduously worked on to extend his recovery). Participants with severe aphasia were excluded from the study recruitment, and they may have less scope to adopt metalinguistic awareness. Further research is needed into supporting such compensatory mechanisms to reduce the negative experiences of communication impairment and compensate for residual losses.

Relying on cues from others such as conversation partners is a strategy that works in the moment to achieve a successful message (‘If someone has a fish …’), although self-generated strategies promote independence, offering reductions in communication breakdown and the semblance of reduced impairment. Masking impairment may present its own sequelae; the sense that others do not understand how hard things are, for example (K.M.’s experience of ‘sounding more normal’ although it does not ‘feel’ normal because the brain is performing a ‘diversion’ to compensate for impairment). Such issues are not metalinguistic but concern adjustments and acceptance, both psychologically and spiritually, beyond the scope of this article.

4.3. Future Directions

The findings show potential for clients to use their metalinguistic insights to inform, develop, and implement strategies to compensate for their impairments. Strategies that may be deemed part of ‘aphasia therapy’ may additionally impact the manifestation of AOS. Reduction of spoken communication breakdown, to ‘fail well’ and maximize successful communication, requires the two disorders to be jointly managed.

Metalanguage is an aspect of self-management that can be overlooked because it is often covert, but it could be significant in a climate of austerity where interventions are economized [34]. Moreover, rather than supplanting impairment-based or conversation partner approaches, an exploration of metalinguistic strategies may proceed in parallel with other therapies, providing a functional holistic approach capable of generalization in everyday life (‘If someone knows how to fish’). Therapists could adopt the neutral questioning approach used in eliciting participant perspectives detailed in Section 2.3, a method that used assessments that were commonly available in SLT services. The use of metaphors (see Section 4.1) for accessing lived experience of word-finding in aphasia may in future be applied to other aspects of metalanguage and with people who also have AOS [56]. Assessments such as the MetAphAs have emerged since the completion of this study with the potential to systematize metalinguistic enquiries. Nevertheless, incorporating metalinguistic reflexivity into existing clinical practice should offer economy of resources and promote self-management beyond therapy.

5. Conclusions

Despite having AOS and aphasia, participants conveyed insights into the processes underlying their communication impairments and strategies, views that need incorporating into SLT interventions. When people with AOS and aphasia are encouraged into metalinguistic dialogue, assessment becomes therapeutic. The application of metalinguistic strategies in people with aphasia and AOS requires SLT assessment to be viewed as a joint discovery owned by participants. Even after discharge from healthcare, metalinguistic strategies can contribute positively to self-management.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

UK Health Service: Main Research Ethics Committee: South Cheshire LREC No. CR100/01.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from L.D. to publish this article.

Data Availability Statement

The additional quantitative data referred to in this study are available in K.M.’s thesis [4].

Acknowledgments

Lesley Dulson (L.D.), a participant in the original study, generously volunteered her feedback in reviewing the accuracy of this article and suggesting amendments. I would like to thank to all participants with AOS and aphasia, hoping that this paper honours their insights. I also acknowledge other SLTs and colleagues who supported me during my doctoral study, especially Jo Frankham and Alys Young, who encouraged me into qualitative research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Participant demographics.

Table A1.

Participant demographics.

| Participant | Gender (M/F) | Age | Months Post-Stroke at 1st Contact | Lesion Site from CT Scan (All Left Hemisphere; (h) Indicates Hematoma) | Previous Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L.D. | F | 45 | 42 | frontoparietal and temporoparietal (h) | Nursing sister |

| B.G. | M | 68 | 30 | parietal | Factory worker |

| J.R. | F | 57 | 23 | frontoparietal | Care worker |

| M.L. | M | 56 | 97 | (no details) | Railway worker |

| D.R. | M | 64 | 9 | ‘middle cerebral artery territory’ | Company director |

| B.S. | M | 69 | 9 | temporoparietal (h) | Factory worker |

| C.E. | M | 54 | 24 | temporoparietal and external capsule | Sales representative |

| R.G. | M | 75 | 12 | frontal | Agricultural worker |

| P.Y. | F | 51 | 4 | no details—later found to be progressive | Secretary |

| A.S. | M | 79 | 12 | parietal | Army/civil servant |

| B.J. | M | 65 | 4 | temporal and parietal | Engineer |

Table A2.

Additional single word assessments from PALPA [57].

Table A2.

Additional single word assessments from PALPA [57].

| Assessment | Max | Norms | Broca’s | Conduction | Anomic | Group | Pilot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | B.G. | J.R. | M.L. | D.R. | B.S. | C.E. | R.G. | P.Y. | A.S. | B.J. | Mean (SD) | L.D. | ||

| Auditory discrimination (PALPA 4) | 40 | 39 (1.70) | 36 | 40 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 40 | 38 | 40 | 36 | 38 (1.56) | 39 |

| Non-word repetition (PALPA 8) | 30 | n/a | 14 | 11 | 20 | 23 | 14 | 1 | 23 | 27 | 17 | 26 | 17.6 (7.95) | 27 |

| Non-word reading (PALPA 8) | 30 | n/a | 4 | 1 | 6 | 23 | 15 | 2 | 15 | 13 | 12 | 6 | 9.7 (7.02) | 3 |

| Auditory rhyme judgement (PALPA 15) | 60 | n/a | 57 | 49 | 46 | 57 | 58 | 50 | 58 | 57 | 53 | 41 | 52.6 (5.91) | 51 |

| Written rhyme judgement (PALPA 15) | 60 | 53.12 (5.10) | 45 | 27 | 32 | 50 | 7 | 40 | 55 | 47 | 50 | 41 | 39.4 (14.21) | 40 |

| Auditory synonyms (PALPA 49) | 60 | n/a | 54 | 40 | 52 | 42 | 57 | 41 | 59 | 58 | 60 | 51 | 51.4 (7.75) | 54 |

| Visual synonyms (PALPA 50) | 60 | 56.75 (2.15) | n/t | 34 | 40 | 51 | 58 | 55 | n/t | 57 | n/t | 51 | 49.43 (9.07) | 60 |

Table A3.

Additional assessments of sentence processing and working memory.

Table A3.

Additional assessments of sentence processing and working memory.

| Max | Norms | A.S. | B.G. | B.J. | B.S. | C.E. | D.R. | J.R. | M.L. | P.Y. | R.G. | Mean (SD) | L.D. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRAMMATICAL DOMAIN | |||||||||||||||

| Test for Reception of Grammar (TROG) [58] (taking data from age 12) | Raw score | 80 | 69 | 70 | 75 | 69 | 58 | 59 | 68 | 68 | 73 | 76 | 68.5 (5.99) | 56 | |

| Standard score | 100 (15) | 89 | 82 | n/a | 71 | 55 | 57 | 71 | 57 | 82 | 98 | 73.56 (15.35) | 67 | ||

| Blocks failed | 20 | abnormal if fail > 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 5.9 (3.75) | 7 | |

| Reversible Sentence Comprehension Test [59] | Actions | 10 | 8 to 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 8.4 (2.12) | 6 |

| Non-actions | 10 | 6 to 10 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 7 (2.67) | 6 | |

| Adjectives | 10 | 7 to 10 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 7.4 (1.65) | 6 | |

| Prepositions | 10 | 8 to 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 9.2 (1.03) | 8 | |

| Total | 40 | 29 to 40 | 30 | 30 | 36 | 33 | 27 | 28 | 35 | 31 | 35 | 35 | 32 (3.23) | 26 | |

| WORKING MEMORY | |||||||||||||||

| Digit span (auditory) | 7 | n/a | 6 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 4.4 (1.96) | 3 | |

| Matching span (auditory) | 7 | n/a | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5.6 (1.35) | 7 | |

| Verbal span (auditory–picture) | 12 | n/a | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3.8 (1.23) | 4 | |

| Corsi blocks (Visuospatial span) | (max forward or back) | 9 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5.2 (0.63) | 6 | |

| scaled score | 10 (3.0) | 10 | 13 | 15 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 14 | 9.9 (3.60) | 8 | ||

References

- Code, C.; Petheram, B. Delivering for aphasia. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2011, 13, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.; Gittins, M.; Tyson, S.; Vail, A.; Conroy, P.; Paley, L.; Bowen, A. Prevalence of aphasia and dysarthria among inpatient stroke survivors: Describing the population, therapy provision and outcomes on discharge. Aphasiology 2020, 35, 950–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronkers, N. A new brain region for coordinating speech articulation. Nature 1996, 384, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumby, K. An Investigation of Apraxia of Speech and Grammar in Connected Speech Following Stroke. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2008. Available online: https://www.librarysearch.manchester.ac.uk/permalink/44MAN_INST/1r887gn/alma992983072351601631 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Molloy, J.; Jagoe, C. Use of diverse diagnostic criteria for acquired apraxia of speech: A scoping review. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2019, 54, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code, C. Contemporary issues in apraxia of speech. Aphasiology 2021, 35, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.C.; Kelly, H.; Godwin, J.; Enderby, P.; Campbell, P. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 6, CD000425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.; Hesketh, A.; Bowen, A. Interventions for apraxia of speech following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 4, CD004298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, B.; Fieder, N.; Nickels, L. Spoken Word Production: Processes and Potential Breakdown. In Handbook of Communication Disorders. Theoretical, Empirical, and Applied Linguistics Perspectives; Bar-On, A., Ravid, D., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, J. Motor Speech Disorders: Substrates, Differential Diagnosis and Management, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2005; pp. 307–334. [Google Scholar]

- Basilakos, A.; Yourganov, G.; den Ouden, D.; Fogerty, D.; Rorden, C.; Feenaughty, L.; Fridrikssona, J. A Multivariate Analytic Approach to the Differential Diagnosis of Apraxia of Speech. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2017, 60, 3369–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, A.; Webster, J.; Howard, D. Assessment and Intervention in Aphasia; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sacristán, C.; Rosell-Clari, V.; Serra-Alegre, E.; Quiles-Climent, J. On natural metalinguistic abilities in aphasia: A preliminary study. Aphasiology 2012, 26, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigaudeau-McKenna, B. Metalinguistic awareness in a case of early-adolescent dysphasia. Clin. Linguist. Phon. 1998, 12, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, D.; Waters, G. On the Nature of the Phonological Output Planning Processes Involved in Verbal Rehearsal—Evidence from Aphasia. Brain Lang. 1995, 48, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fama, M.; Snider, S.; Henderson, M.; Hayward, W.; Friedman, R.; Turkeltaub, P. The Subjective Experience of Inner Speech in Aphasia Is a Meaningful Reflection of Lexical Retrieval. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2019, 62, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fama, M.; Lemonds, E.; Levinson, G. The Subjective Experience of Word-Finding Difficulties in People with Aphasia: A Thematic Analysis of Interview Data. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2022, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.B.; Carlsson, M.; Sonnander, K. Communication difficulties and the use of communication strategies: From the perspective of individuals with aphasia. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2012, 47, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickels, L. Spoken Word Production and Its Breakdown in Aphasia; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nickels, L. The autocue? Self-generated phonemic cues in the treatment of a disorder of reading and naming. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 1992, 9, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeDe, G.; Parris, D.; Waters, G. Teaching self-cues: A treatment approach for verbal naming. Aphasiology 2003, 17, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, V. How to turn interior monologues inside out: Epistemologies, methods, and research tools in the long twentieth century. Sound Stud. 2020, 6, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, S.; Inglis, A.; Dyson, L.; Roper, A.; Harbottle, A.; Ryder, J.; Cowell, P.; Varley, R. Error reduction therapy in reducing struggle and grope behaviours in apraxia of speech. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2012, 22, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, A. Self-correction in apraxia of speech: The effect of treatment. Aphasiology 2007, 21, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.-K.; Azuma, T.; Mathy, P.; Liss, J.; Edgar, J. The effect of home computer practice on naming in individuals with nonfluent aphasia and verbal apraxia. J. Med. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2007, 15, 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow, R. Listening to the voice of living life with aphasia: Anne’s story. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2008, 43, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]