Supporting Autistic Pupils in Primary Schools in Ireland: Are Autism Special Classes a Model of Inclusion or Isolation?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Ireland’s Policy Response to Educational Provision for Autistic Students

1.2. Autism Special Class Provision: An Enduring Model of Inclusion or Isolation?

- What are the benefits of and challenges attributed to having an autism class in mainstream primary schools?

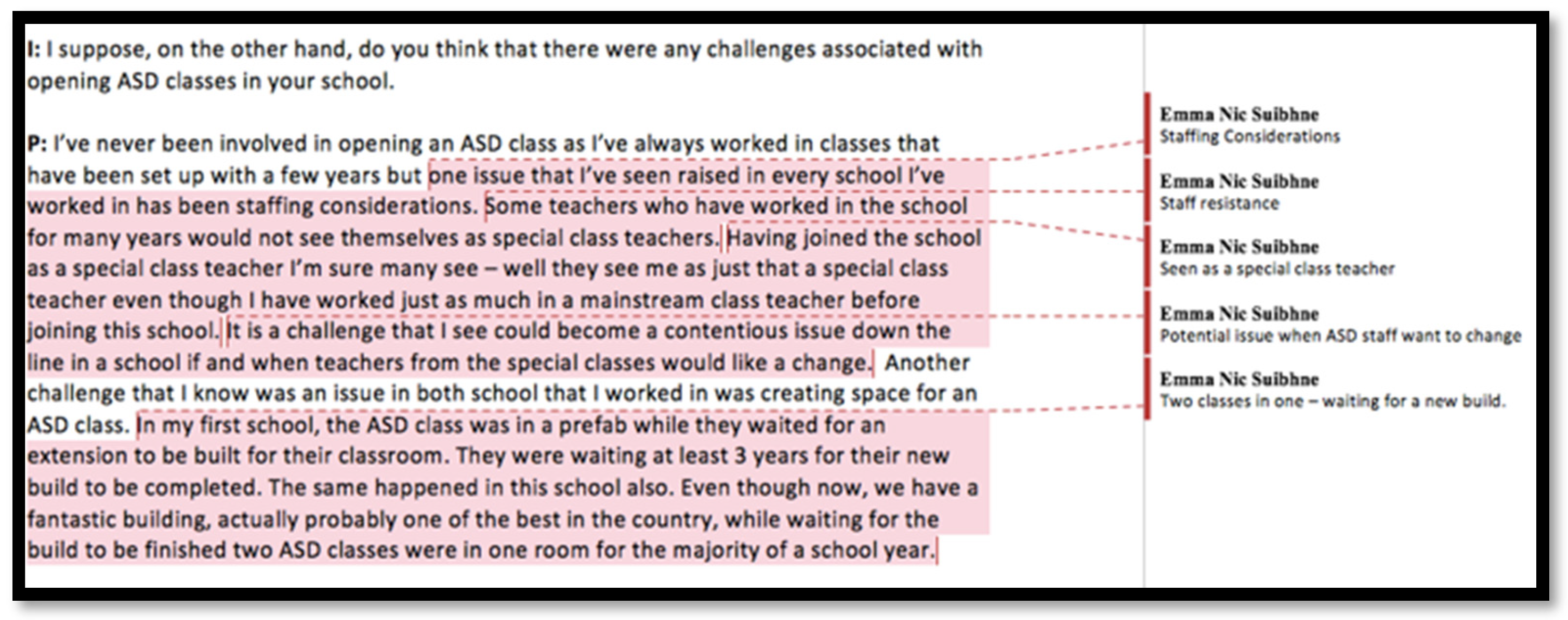

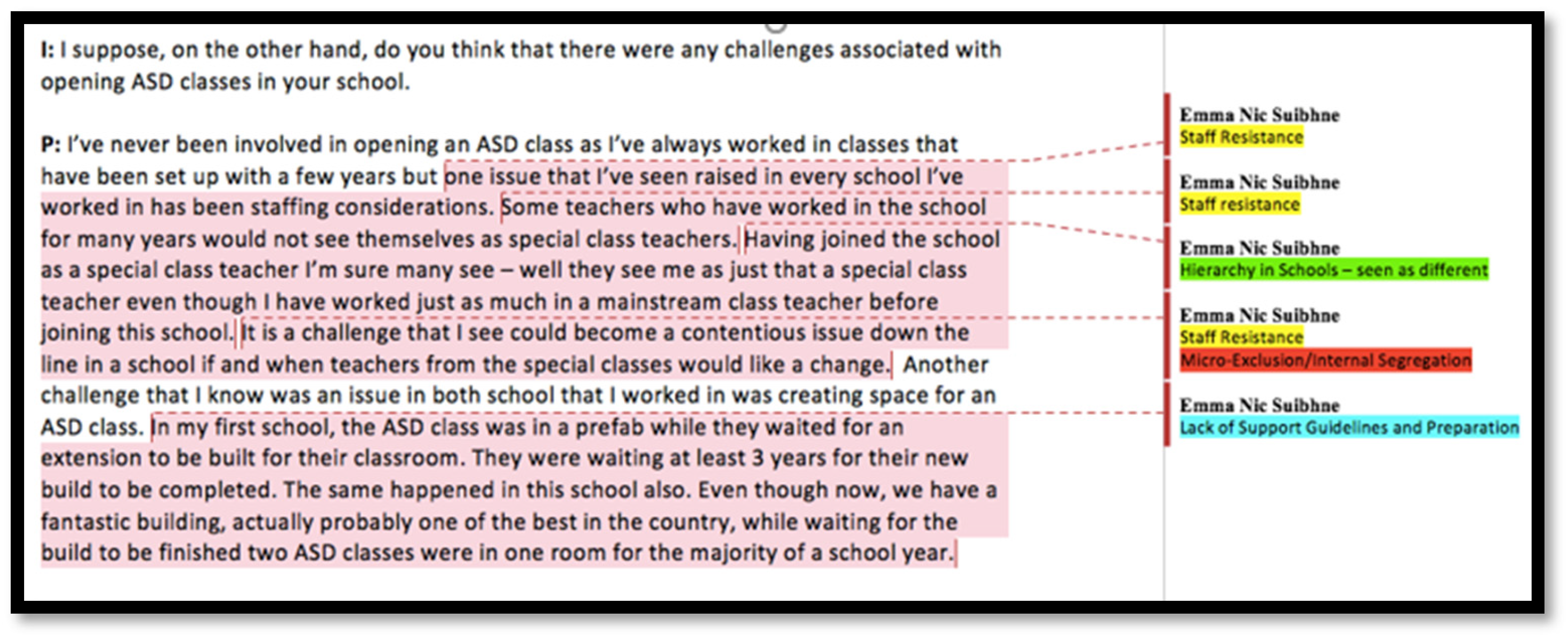

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Research

2.2. Sem-Structured Interviews

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Trustworthiness of the Findings

3. Findings

- What are the benefits of and challenges attributed to having an autism special class in mainstream schools?

- School leadership is critical to support a collaborative schoolwide approach to inclusion of the autism special class, but principals need support to lead.

- Access to high-quality, autism-specific professional learning promotes learning for autistic students.

- Autism special classes represent models of integration rather than inclusion in Irish primary schools.

3.1. School Leadership Is Critical to Support a Collaborative Schoolwide Approach to Inclusion of the Autism Special Class, but School Leaders Need Support to Lead

‘if the Department [of Education] want to continue to present this model and I think that it’s a very good model, I think that they should spend much more time educating staff, giving greater guidance to management regarding specifications of rooms… and upskilling the staff as a whole on how to deal generally with children with autism because I don’t think that is being done’.(P2)

3.2. Access to High-Quality, Autism-Specific Professional Learning Promotes Learning for Autistic Students

3.3. Autism Special Classes Represent a Model of Integration Rather Than Inclusion in Irish Primary Schools

‘even though we shouldn’t be using the word unit […] even though Emma if you call it another name it still comes back’.(P1)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bond, C.; Symes, W.; Hebron, J.; Humphrey, N.; Morewood, G. Educating Persons with Autistic Spectrum Disorder—A Systematic Literature Review; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. Estimating Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in the Irish Population: A Review of Data Sources and Epidemiological Studies; Stationary Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elsabbagh, M.; Divan, G.; Koh, Y.J.; Young, S.K.; Kauchali, S.; Marcin, C.; Montiel-Nava, C.; Patel, V.; Paula, C.S.; Wang, C.; et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 2012, 5, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, S.; Shevlin, M. Responding to Special Educational Needs: An Irish Perspective, 2nd ed.; Gill and MacMillan: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Special Education. Policy Advice on Special Schools and Classes: An Inclusive Education for an Inclusive Society? National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R.; Shevlin, M. Establishing Pathways to Inclusion; Investigating the Experiences and Outcomes for Students with Special Educational Needs; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. Education Act; The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. The Education (Welfare) Act; Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. Equal Status Act; Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act (2004); The Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. Disability Act; Stationery Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin, M.; Banks, J. Inclusion at a Crossroads: Dismantling Ireland’s System of Special Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee on Autism Debate, Josepha Madigan. Available online: https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/joint_committee_on_autism/2022-07-05/2/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Case-Smith, J.; Weaver, L.; Fristad, M.A. A systematic review of sensory processing interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2015, 19, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Education and Skills. The Report of the Task Force on Autism; Department of Education and Skills, Stationary Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate. Evaluation of Autism Provision; Department of Education and Skills: Dublin, Ireland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, P.; Ring, E.; Egan, M.; Fitzgerald, J.; Griffin, C.; Long, S.; McCarthy, E.; Moloney, M.; O’Brien, T.; O’Byrne, A.; et al. An Evaluation of Education Provision for Children with Autism in Ireland; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.; McCoy, S.; Frawley, D.; Kingston, G.; Shevlin, M.; Smyth, F. Special Classes in Irish Schools—Phase 2: A Qualitative Study; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate. Educational Provision for Learners with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Special Classes Attached to Mainstream Schools in Ireland; Department of Education and Skills: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, M. Effective Teaching Strategies to Promote Successful Learning. In Autism from the Inside Out: A Handbook for Parents, Early Childhood, Primary, Post-Primary and Special School Settings; Ring, E., Daly, P., Wall, E., Eds.; Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff, E.; Jones, C.R.G.; Baird, G.; Pickles, A.; Happe, F.; Charman, T. The persistence and stability of psychiatric problems in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 54, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croydon, A.; Remington, A.; Kenny, L. ‘This is what we’ve always wanted’: Perspectives on young autistic people’s transition from special school to mainstream satellite classes. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2019, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNerney, C.; Hill, V.; Pellicano, E. Choosing a secondary school placement for students with an autism spectrum condition: A multi-informant study. Int. J. of Incl. Ed. 2015, 19, 1096–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ireland. Autism Good Practice Guidance for Schools—Supporting Children and Young People. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/246065/ca72e39e-e657-4d3d-82ed-83e1d0122c8f.pdf#page=null (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Department of Education and Skills. Inclusion of Students with Special Educational Needs: Primary Guidelines; Stationary Office: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rix, J.; Sheehy, K.; Fletcher-Campbell Felicity Crisp, M.; Harper, A. Continuum of Education Provision with Special Education Needs: Review of International Policies and Practices; National Council for Special Education: Trim, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R.; Shevlin, M.; Winter, E.; O’Raw, P.; Zhao, U. Individual education plans in the Republic of Ireland: An emerging system. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2012, 39, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, T.; Shevlin, M.; Donovan, M.; Gercke, M.; Goll, H.; Šiška, J.; Janyšková, K.; Smogorzewska, J.; Szumski, G.; Vlachou, A.; et al. Same Progress for All? Inclusive Education, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Students with Intellectual Disability in European Countries. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 18, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersold, S. Inclusive Education for Young Disabled People in Europe: Trends, Issues and Challenges, A synthesis of Evidence from ANED Country Reports and Additional Sources; National Higher Institute for Training and Research on Special Needs Education, INSHEA: Suresnes, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, D.; Meyen, E. Special Education Teacher Education: A Perspective on Content Knowledge. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2009, 24, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S. Developing Knowledge and Understanding of Autism Spectrum Difference. In Autism from the Inside Out: A Handbook for Parents, Early Childhood, Primary, Post-Primary and Special School Settings; Ring, E., Daly, P., Wall, E., Eds.; Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, K. Effective Practices for Teaching All Learners in Secondary Classrooms. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. The Psychology of Behaviour at Work, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, H. Case Study Research in Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant, L.; Rose, K.; Whalon, K. Supporting Students with Autism: A lesson embedded with strategies addressing students with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Teach. 2017, 84, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative and Mixed Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.; Crabtree, B. RWJF—Qualitative Research Guidelines Project. Triangulation. Available online: http://www.qualres.org/HomeTria-3692.html (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Yu, F. Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology with Examples. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.; Lincoln, Y. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research. Qual. Res. 2001, 3, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Into Pract. 2000, 3, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, J.; Giust, A. Elements of Research Questions in Relation to Qualitative Inquiry. Qual. Rep. 2019, 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, J.; Lynch, J.; Martin, A.; Cullen, B. Leading Inclusive Learning, Teaching and Assessment in Post-Primary Schools in Ireland: Does Provision Mapping Support an Integrated, School-Wide and Systematic Approach to Inclusive Special Education? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G. How Distributed Leadership can Make a Difference in Teachers’ Organizational Commitment? A Qualitative Study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, J.; Balfe, T. Addressing the Challenges and Barriers to Inclusive Education in Irish Primary Schools; St. Patrick’s College: Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The Teaching Council. Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education; The Teaching Council: Kildare, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. Autism Good Practice Guidance for Schools—Supporting Children and Young People. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/8d539-autism-good-practice-guidance-for-schools-supporting-children-and-young-people/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

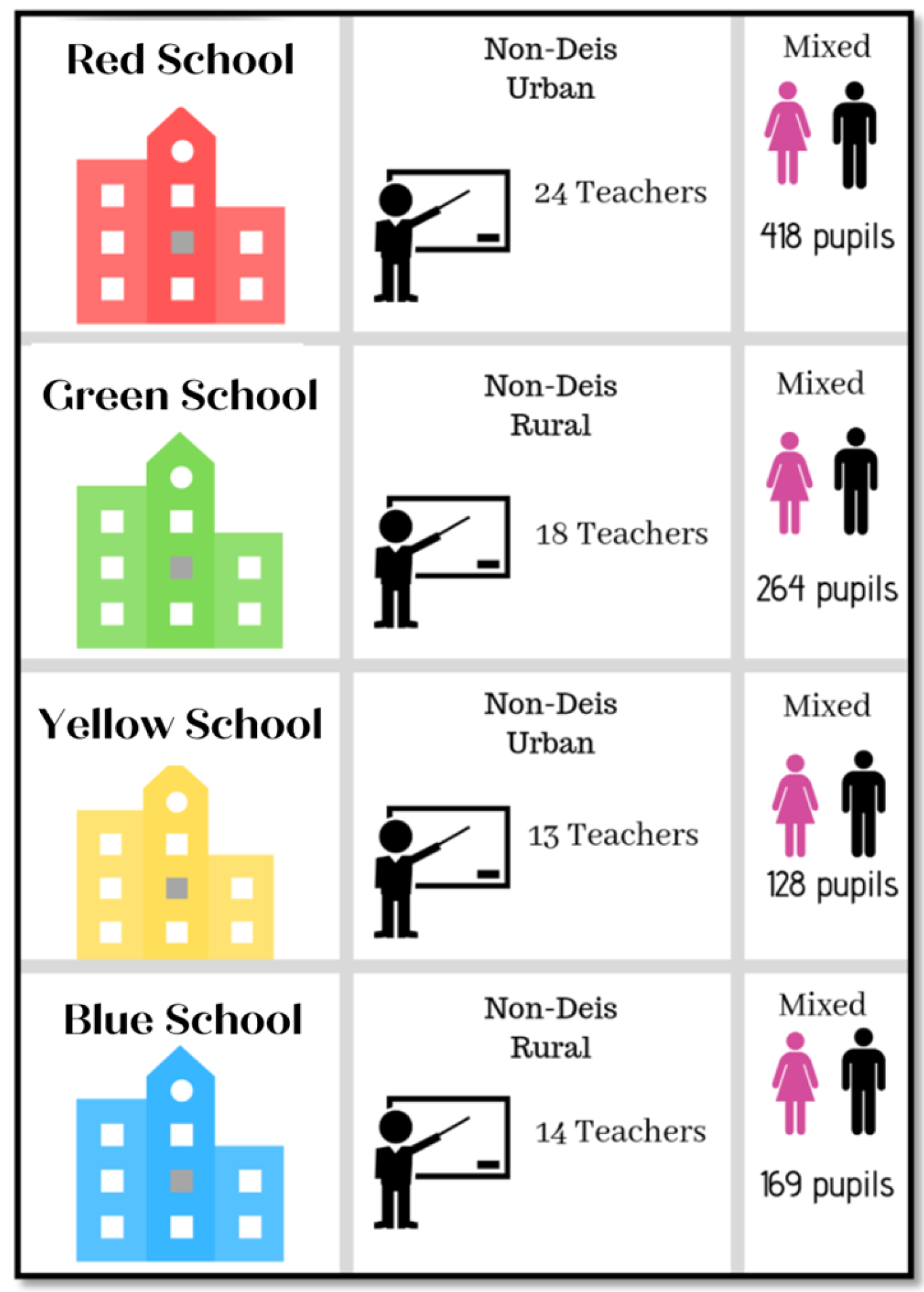

| School Pseudonym | Teacher | Gender | School Area | School Type | Number of Teachers | Teacher Classification | Teacher Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red School | Principal 1 | Male | Urban | Co-educational | 24 | Administrative | P1 |

| Green School | Principal 2 | Male | Rural | Co-educational | 18 | Administrative | P2 |

| Yellow School | Principal 3 | Female | Urban | Co-educational | 13 | Administrative | P3 |

| Blue School | Principal 4 | Female | Rural | Co-educational | 14 | Administrative | P4 |

| Red School | Mainstream Teacher 1 | Female | Urban | Co-educational | 24 | Mainstream-infants | M1 |

| Green School | Mainstream Teacher 2 | Female | Rural | Co-educational | 18 | Mainstream-1st and 2nd | M2 |

| Yellow School | Mainstream Teacher 3 | Female | Urban | Co-educational | 13 | Mainstream-infants | M3 |

| Blue School | Mainstream Teacher 4 | Female | Rural | Co-educational | 14 | Mainstream-3rd and 4th | M4 |

| Red School | Autism Class Teacher 1 | Female | Urban | Co-educational | 24 | Autism class (3–12 years) | ACT1 |

| Green School | Autism Class Teacher 2 | Female | Rural | Co-educational | 18 | Junior Autism Class | ACT2 |

| Yellow School | Autism Class Teacher 3 | Female | Urban | Co-educational | 13 | Middle Autism Class | ACT3 |

| Blue School | Autism Class Teacher 4 | Male | Rural | Co-educational | 14 | Senior Autism Class | ACT4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sweeney, E.; Fitzgerald, J. Supporting Autistic Pupils in Primary Schools in Ireland: Are Autism Special Classes a Model of Inclusion or Isolation? Disabilities 2023, 3, 379-395. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030025

Sweeney E, Fitzgerald J. Supporting Autistic Pupils in Primary Schools in Ireland: Are Autism Special Classes a Model of Inclusion or Isolation? Disabilities. 2023; 3(3):379-395. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030025

Chicago/Turabian StyleSweeney, Emma, and Johanna Fitzgerald. 2023. "Supporting Autistic Pupils in Primary Schools in Ireland: Are Autism Special Classes a Model of Inclusion or Isolation?" Disabilities 3, no. 3: 379-395. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030025

APA StyleSweeney, E., & Fitzgerald, J. (2023). Supporting Autistic Pupils in Primary Schools in Ireland: Are Autism Special Classes a Model of Inclusion or Isolation? Disabilities, 3(3), 379-395. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030025