Exploration of a Strengths-Based Rehabilitation Perspective with Adults Living with Multiple Sclerosis or Spinal Cord Injury

Abstract

:1. Introduction

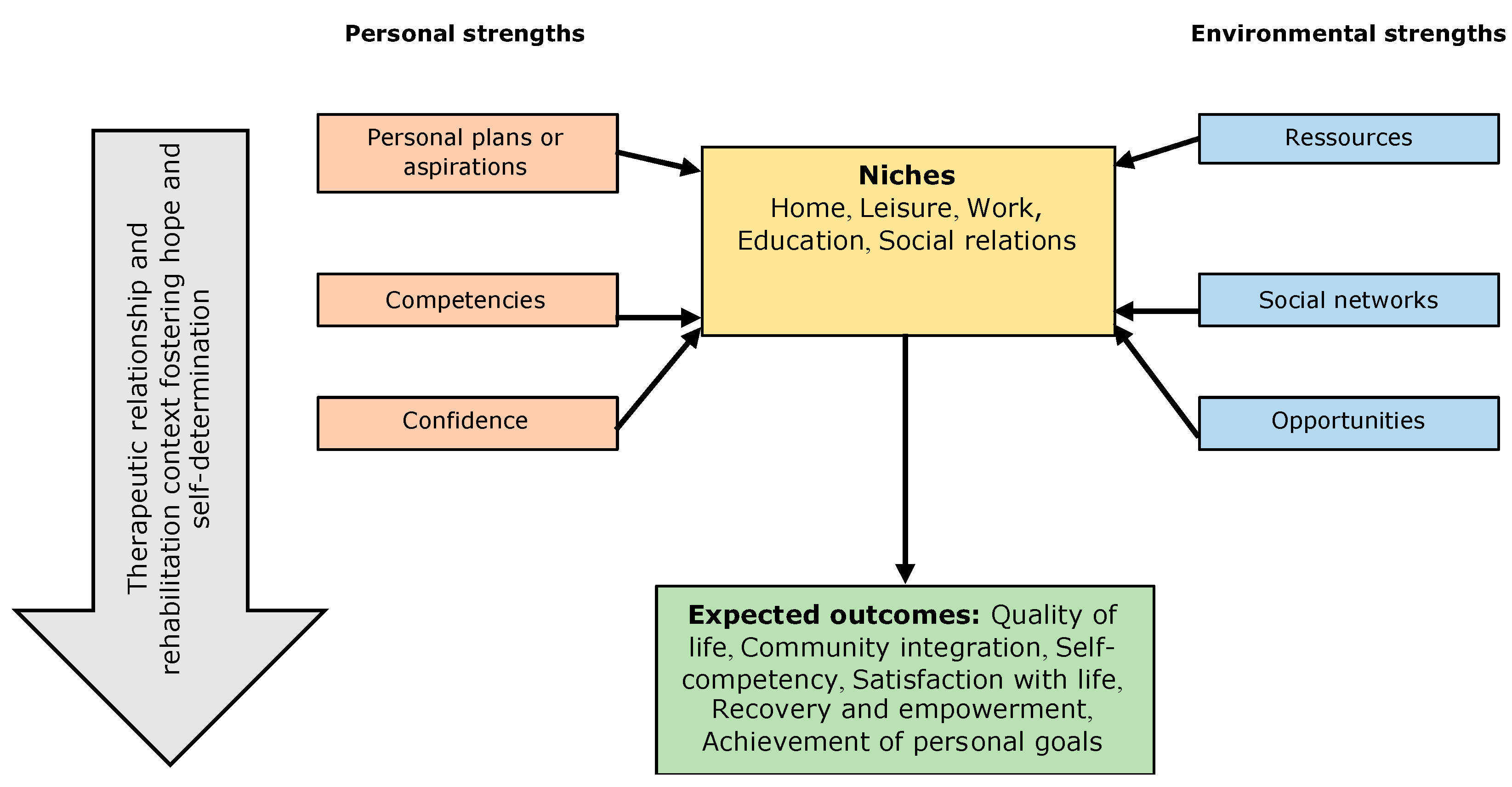

1.1. The Strengths Model

1.2. Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Sampling Strategy and Recruitment

2.3. Qualitative Interviews

2.4. Quantitative Measures

2.5. Procedures

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Recovery Promoting Relationship Scale (RPRS)

3.3. Mobilization of Personal Strengths

“Beyond the fact that I am hard working and that I like to train, to my knowledge, they did not use any of my other strengths or talents during my rehabilitation.”(Participant 11; 52-year-old woman living with MS for 28 years)

“For me, resilience is being able to ask for help and assuming that you cannot do it all alone. Resilience… I would say that I have plenty of it and that they put it to good use.”(Participant 14; 54-year-old man living with MS for 20 years).

“They put the emphasis on everything that was physical, like … ‘You have strong arms. Use them!’ But... as for the rest, anything related to intellect, for example, no, we did not use that.”(Participant 1; 40-year-old man living with SCI for one year)

“My active side, in physio... They adapted to my interest in sports. In OT, as I told you, we used Wii Sport and ping-pong because of that as well.”(Participant 13; 37-year-old man living with SCI for two years)

“I am still a nurse! I was in school long enough not to want to organize small metal pieces as a job! I want to leave home and be motivated to go to rehabilitation, not get frustrated.”(Participant 19; 38-year-old woman living with MS for 17 years).

“With the social worker, we went to see for the Farmers’ Circle because I really like everything that is manual. And I am good at it. We explored participation opportunities there.”(Participant 17; 46-year-old woman living with SCI for 12 years)

“Working from someone’s strengths is rewarding; it’s encouraging. It’s interesting! It can help with self-esteem. It encourages me to progress, to improve myself. It allows me to become aware of my skills, but also to develop them.”(Participant 12; 31-year-old man living with SCI for 17 years)

“A focus on strengths brings a whole new dimension to rehabilitation. That’s where one can get people’s interest, it’s going to get them motivated.” You stick to rehabilitation; it’s going to make you go further and have better results.”(Participant 13; 37-year-old man living with SCI for two years)

3.4. Hope

“My physiotherapist told me, ‘You get up and walk.’ I did it. And then you realize what you are capable of. I came out of there stunned, especially during the first treatments, every little detail you see that you can do… it’s really inspiring.”(Participant 8; 28-year-old woman living with SCI for one year)

“I was able to see progress every week. Progress in my rehabilitation, my abilities. Seeing that I was able to do more and always better. It was a source of motivation and hope.”(Participant 13; 37-year-old man living with SCI for two years)

“Hope is complex and very personal, you know. I think the team is doing all they can… the PTs, the OTs. The fact that they encourage us, that they tell us that we will reach our personal goals... that we are moving forward. It helps.”(Participant 15; 58-year-old woman living with MS for four years)

“The rehabilitation team was talking to me about the results we got working on together toward my objectives. They supported my motivation. They showed me that there had been improvements regarding my personal goals.”(Participant 11; 52-year-old woman living with MS for 28 years)

“At the beginning of the meetings with the PT, you set your objectives and you talk a lot. I mean, she never said to me that my goals were impossible or that I would never get there… but I still kind of perceived it [crying].”(Participant 15; 58-year-old woman living with MS for four years)

“You feel there is a wait. We wait for the six weeks to end, and we wait for the intervention plan before doing any action or making any change. We’re waiting for the 6-week program to finish. We’re going to do the same things instead of giving you hope and trying things.”(Participant 2; 35-year-old man living with SCI for one year)

“Everything is sequential. For example, my therapist told me that the driving program came after the physical program, which greatly lengthens the time you spend there. You get discouraged with the time it takes to get to the next step.”(Participant 7; 54-year-old man living with SCI for two years)

3.5. Accessing Information for Decision-Making

“First, you have to know... You have to understand the purpose of the sessions. At first, you do not know! You go in there and you do not know what the purpose is.”(Participant 2; 35-year-old man living with SCI for one year)

“It could have been in the social worker’s mandate to explain what was going to happen in these sessions… or what questions I would have to answer in order to be better prepared. If you are not prepared, your whole rehabilitation will be impacted.”(Participant 13; 37-year-old man living with SCI for two years).

“I would have liked information on how to get psychological help [...]. I found myself in a twilight zone in this regard I would have liked to have sessions that told me which doors to knock on to get this type of help... psychological help.”(Participant 7; 54-year-old man living with SCI for two years)

“If I knew what the crucial information was to make good decisions for my rehabilitation, I would probably still be doing rehabilitation right now. I imagine that you have to know your deficits and from there, know on which doors to knock in order to overcome them.”(Participant 19; 38-year-old woman living with MS for 17 years).

“It’s important to know the role of the different therapists and it’s complex; it always has been. You know, a PT, an OT... It’s difficult to navigate and we do not always know who to ask our questions to or who to address our requests to. Do I need an OT or PT?”(Participant 15; 58-year-old woman living with MS for four years)

“I only spoke in neuropsychology about my social relations. […] I wasn’t talking about this with my OT, for example… She will not help me at that level. It’s not her role.”(Participant 12; 31-year-old man living with SCI for 17 years).

“Nothing was done about my plan to walk outside a bit more… I do not know what exists or what they can offer me [...] The how and the who… I have no idea! I do not even know if there is any help for that. Is it offered at the rehabilitation centre?”(Participant 19; 38-year-old woman living with MS for 17 years)

3.6. Exercising Self-Determination

“The goals that I set for myself every month. That’s what we do during the treatment planning sessions. Having goals and challenges, but also having a team that accompanies me helps. I am the master of my treatment planning sessions, the master of my rehabilitation.”(Participant 7; 54-year-old man living with SCI for two years)

“I did not have a word to say in the choice of goals... I did not even know which goals I needed or even reached throughout rehabilitation. [...] What they expected from me… I was not told.”(Participant 10; 56-year-old woman living with MS for one year)

“My goal… It’s almost my secret garden because of what I have heard from them about what we can achieve… I do not talk to them much and I dream, I dream.”(Participant 1; 40-year-old man living with SCI for one year)

“In occupational therapy, I had seen some type of special clothespins and I wanted them at home so that I could work on my dexterity. They ordered them for me directly from the catalog. They really helped me find the means to address my needs.”(Participant 13; 37-year-old man living with SCI for two years)

“I wanted to do workshops, some manual work as therapy during my rehabilitation. My OT told me that she did not like it; that she had another approach. During vacation replacement, the same thing happened. I wanted to do some workshops, but she wanted to do Wii.”(Participant 5; 47-year-old woman living with SCI for eight years)

“I did not make the decision to end my rehabilitation. It was the PT who told me we had finished. She had brought me where she wanted to take me, so it was the end. Personally, I would have liked to continue. She told me that I could call back if I needed other exercises.”(Participant 9; 55-year-old man living with MS for eight years)

“I was in the social integration program and for this, the question of exploring opportunities for participation, they clearly told me that it was over. No more services. I had no power over this. As for the physical aspect, there was an opening though.”(Participant 17; 46-year-old woman living with SCI for 12 years)

“What I realized was that at the center you are surrounded a lot, but when you get there, they already see the exit and they tell you about it.”(Participant 5; 47-year-old woman living with SCI for eight years)

“Currently, I sometimes feel that I should leave and make room for someone else when I’m not progressing.”(Participant 1; 40-year-old man living with SCI for one year)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Futures Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rapp, C.A.; Goscha, R. The Strengths Model: Case Management with People with Psychiatric Disabilities, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, C.A.; Goscha, R. The Strengths Model: A Recovery-Oriented Approach to Mental Health Services, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Björkman, T.H.; Sandlund, M.L. Outcome of case management based on the strengths model compared to standard care. A randomised controlled trial. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2002, 37, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, S.; Goscha, R.; Rapp, C.A.; Mabry, A.; Liddy, P.; Marty, D. Strengths Model Case Management Fidelity Score and Client Outcomes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 708–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanard, R. The Effect of Training in a Strengths Model of Case Management on Client Outcomes in a Community Mental Health Center. Community Ment. Health J. 1999, 35, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tsoi, E.W.; Hamilton, B.; O’Hagan, M.; Shepherd, G.; Slade, M.; Whitley, R.; Petrakis, M. Uses of strength-based interventions for people with serious mental illness: A critical review. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 62, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.; Baptiste, S.; Mills, J. Client-Centred Practice: What does it Mean and Does it Make a Difference? Can. J. Occup. Ther. 1995, 62, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A.; Roskell, C.; Elder, T.; Collett, J.; Dawes, H. The psychological processes of adaptation and hope in patients with multiple sclerosis: A thematic synthesis. Open J. Ther. Rehabil. 2016, 4, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilkins, S.; Pollock, N.; Rochon, S.; Law, M. Implementing client-centred practice: Why is it so difficult to do? Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2001, 68, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, J.; Evans, J.; Baldwin, P. The importance of self-determination to perceived quality of life for youth and young adults with chronic conditions and disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2010, 31, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, M.L. Self-determination and the empowerment of people with disabilities. Am. Rehabil. 2004, 28, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, E.A.; Polatajko, H.J. Enabling Occupation II: Advancing an Occupational Therapy Vision for Health, Well-Being & Justice through Occupation; CAOT Publications ACE: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007; 418p. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.R. Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind. Psychol. Inq. 2002, 13, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Lopez, S.J.; Shorey, H.S.; Rand, K.L.; Feldman, D.B. Hope theory, measurements, and applications to school psychology. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2003, 18, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lynch, S.G.; Kroencke, D.C.; Denney, D.R. The relationship between disability and depression in multiple sclerosis: The role of uncertainty, coping, and hope. Mult. Scler. J. 2001, 7, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, A.W.; Piazza, D.; Holcombe, J.; Paul, P.; Daffin, P. Hope, self-esteem and social support in persons with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. J. Am. Assoc. Neurosci. Nurses 1990, 22, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, S.; Pakenham, K.I. The stress-buffering effects of hope on changes in adjustment to caregiving in multiple sclerosis. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, S.; Martin, J.; Miller, R.; Ward, M.; Wehmeyer, M. A Practical Guide for Teaching Self-Determination; Council for Exceptional Children: Reston, VA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, M.J.; Craddock, G.; Mackeogh, T. The relationship of personal factors and subjective well-being to the use of assistive technology devices. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammell, K.R. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord 2007, 45, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peter, C.; Rauch, A.; Cieza, A.; Geyh, S. Stress, internal resources and functioning in a person with spinal cord disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2012, 30, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haymes, L.K.; Cote, D.L.; Storey, K. Improving Community Integration and Participation. In Advances in Exercise and Health for People with Mobility Limitations; Hollard, D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, W. Strengths-based approaches: What if even the ‘bad’ things are good things? Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 80, 395–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.; Koenig, K.; Cox, J.; Sabata, D.; Pope, E.; Foster, L.; Blackwell, A. Harnessing strengths: Daring to celebrate everyone’s unique contributions (part I). Dev. Disabil. Spec. Interest Sect. Q. 2013, 36, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, W.; Koenig, K.; Cox, J.; Sabata, D.; Pope, E.; Foster, L.; Blackwell, A. Harnessing strengths: Daring to celebrate everyone’s unique contributions (part II). Dev. Disabil. Spec. Interest Sect. Q. 2013, 36, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks, S.; Lapum, J.; Schwind, J.; Beanlands, H.; Romaniuk, D.; McCay, E. Discussion of patient-centered care in health care organizations. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2012, 21, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.; Turpin, M.J. Intentional strengths interviewing in occupational justice research. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulock, H. Research Design: Descriptive Research. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 1993, 10, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M.F.; Gagnon, J. Fondements et Étapes du Processus de Recherche Méthodes Quantitatives et Qualitatives, 3rd ed.; Chenelière Éducation: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte, S.; Vallée, C.; Vincent, C. Occupational therapy and community integration of adults with neurological conditions: A scoping review. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 85, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russinova, Z.; Rogers, E.S.; Cook, K.F.; Ellison, M.L.; Lyass, A. Conceptualization and measurement of mental health providers’ recovery-promoting competence: The recovery promoting relationships scale (RPRS). Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russinova, Z.; Rogers, E.S.; Ellison, M.L.; Lyass, A. Recovery-promoting professional competencies: Perspectives of mental health consumers, consumer-providers and providers. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2011, 34, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilrycx, G.; Croon, M.A.; van den Broek, A.; van Nieuwenhuizen, C. Psychometric properties of three instruments to measure recovery. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 26, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McColl, M.A.; Davies, D.; Carlson, P.; Johnston, J.; Minnes, P. The community integration measure: Development and preliminary validation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 82, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J. L’Échelle de provisions sociales: Une validation québécoise. Sante Ment. Que. 1996, 21, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthey, T.J.; Knowles, B.; Asher, D.; Wahab, S. Strengths-based practice and motivational interviewing. Adv. Soc. Work. 2011, 12, 126–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sumsion, T.; Lencucha, R. Balancing challenges and facilitating factors when implementing client-centred collaboration in a mental health setting. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2007, 70, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumbardó-Adam, C.; Vicente Sánchez, E.; Simó-Pinatella, D.; Coma Roselló, T. Understanding practitioners’ needs in supporting self-determination in people with intellectual disability. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2020, 51, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, C.A.; Nathanson, R.; Baker, S.R.; Tamura, R. Self-determination: What do special educators know and where do they learn it? Remedial Spec. Educ. 2002, 23, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundy, A.; Smith, B.; Butler, M.; Minns Lowe, C.; Helen, D.; Winward, C.H. A qualitative study in neurological physiotherapy and hope: Beyond physical improvement. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2010, 26, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J.; Yaghmaian, R.; Brooks, J.; Fais, C.; Chan, F. Attachment, hope, and participation: Testing an expanded model of Snyder’s hope theory for prediction of participation for individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2018, 63, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsett, P.; Geraghty, T.; Sinnott, A.; Acland, R. Hope, coping and psychosocial adjustment after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2017, 3, 17046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phillips, B.N.; Smedema, S.M.; Fleming, A.R.; Sung, C.; Allen, M.G. Mediators of disability and hope for people with spinal cord injury. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 1672–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazeau, H.; Davis, C.G. Hope and psychological health and well-being following spinal cord injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2018, 63, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theory-Driven Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Mobilization of personal strength | Place for personal plans or aspirations Personal strengths or skills mobilized in rehabilitation What a strengths-based perspective could offer |

| Hope | Things supporting hope during rehabilitation Things hindering hope during rehabilitation |

| Accessing information for decision-making | Information needed Navigating the system Perceptions/understanding of therapists’ roles Representation of rehabilitation mandate |

| Exercising self-determination | Goals, personal priorities, and rehabilitation objectives Preferences in interventions What can help exercising self-determination Influencing the length or intensity of rehabilitation services |

| Population | Age (Year) | Gender (n) | Time Since Diagnosis (Year) | Marital Status (n) | Annual Family Income (CAD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean [Range] | Women:Men | Mean [Range] | Single or Divorced | Married or Civil Union | <50 k | between 50 k and 100 k | >100 k | |

| SCI (n = 9) | 42.6 [28–65] | 4:5 | 9.3 [1–40] | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| MS (n = 11) | 54.4 [38–65] | 9:2 | 14.9 [1–28] | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| Total (n = 20) | 48.5 [28–65] | 13:7 | 12.1 [1–40] | 8 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 2 |

| Rehabilitation Programs | Participant ID |

|---|---|

| Social integration support program (SISP) | 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 |

| Spinal cord injury program (SCIP) | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 13 |

| MS rehabilitation clinic (MSRC) | 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 20 |

| Population | Total Score (/100) | Indexes & Subscales (/100) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Relationship Index | Recovery-Promoting Strategies Index | Hope Subscale | Empowerment Subscale | Self-Acceptance Subscale | ||

| Means [Ranges] | ||||||

| SCI (n = 9) | 75.4 [61–89] | 91.2 [68–100] | 75.1 [61–88] | 81.9 [67–100] | 80.3 [38–100] | 81.9 [57–100] |

| MS (n = 11) | 75 [52–100] | 96.8 [65–100] | 73.7 [44–100] | 85.7 [43–100] | 78.25 [41–100] | 85.1 [42–100] |

| Total (n = 20) | 75.2 | 94.3 | 74.4 | 84 | 79.4 | 83.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turcotte, S.; Vallée, C.; Vincent, C. Exploration of a Strengths-Based Rehabilitation Perspective with Adults Living with Multiple Sclerosis or Spinal Cord Injury. Disabilities 2023, 3, 352-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030023

Turcotte S, Vallée C, Vincent C. Exploration of a Strengths-Based Rehabilitation Perspective with Adults Living with Multiple Sclerosis or Spinal Cord Injury. Disabilities. 2023; 3(3):352-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030023

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurcotte, Samuel, Catherine Vallée, and Claude Vincent. 2023. "Exploration of a Strengths-Based Rehabilitation Perspective with Adults Living with Multiple Sclerosis or Spinal Cord Injury" Disabilities 3, no. 3: 352-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030023

APA StyleTurcotte, S., Vallée, C., & Vincent, C. (2023). Exploration of a Strengths-Based Rehabilitation Perspective with Adults Living with Multiple Sclerosis or Spinal Cord Injury. Disabilities, 3(3), 352-366. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities3030023