1. Introduction

This paper reflects on the experiences of disabled people in Ireland, as they negotiate and engage with personal assistance (PA) services that are intended to support their independent living. It draws on a large-scale mixed-method study with disabled people, undertaken during summer and autumn, 2021. The approach included a multimode survey with PA service users, followed by in-depth interviews with selected service users with differing profiles and experiences. Framed within an emancipatory research approach, the planning and implementation of the survey and qualitative interviews, and the interpretation of the findings, were done in conjunction with disabled people and advocacy groups. The research draws on a capability approach, focusing on the voices, preferences and experiences of PA service users and their reflections on the role of PA supports in supporting the functionings they want to achieve.

In line with Irish policy, a personal assistant is defined as someone “employed by the person with a disability to enable them to live an independent life. The personal assistant provides assistance, at the discretion and direction of the person with the disability, thus promoting choice and control for the person with the disability to live independently” [

1]. It should be noted here that the phrase “employed by” is understood by the HSE and service providers as meaning that the service user has full control over the personal assistant. In the conventional sense of the term, most personal assistants are employed by service provider organisations on behalf of service users, using the funding allocated to that service user. Two main forms of personal support services are funded by the Irish government through the publicly funded healthcare system, the Health Service Executive (HSE): Home Support Service and Personal Assistance hours. Personal assistance services are provided primarily to persons with physical and sensory disabilities; persons with disabilities over the age of 65 are not eligible for personal assistance in Ireland [

2]. The Home Support Service provides home care and home assistance, typically understood in Ireland as support at home with cleaning, cooking and other light household tasks that an individual is unable to do due to a disability, although this scope has expanded to include assistance with personal care, such as hygiene and dressing [

3]. Recent appraisals of this system [

2,

4] suggest there may be a degree of interchangeability between these two services for persons with disabilities. There should be a clear distinction in the level of control over supports exercised by the two groups: as will be discussed, personal assistance should be controlled by the user in terms of both the scheduling of hours and the supports those hours are used for, while home support is framed in a much more prescriptive way. How well the Irish system meets this criterion will be a key focus of this paper.

An earlier stage in this research considered aspects of PA provision from the perspective of insiders, eliciting the views and experiences of service providers and state-based institutional stakeholders regarding the PA system and its challenges. A two-step exploratory mixed-method design, incorporating a series of qualitative interviews and a survey of Health Service Executive (HSE) disability managers, provided insights into the nature of PA provision in Ireland. The findings highlighted critical issues relating to under-funding, inadequate administrative data records and variation in allocation and provision across the country [

4]. The findings gave us an understanding of likely issues facing service users in accessing adequate PA and directing their PA, with particular issues around the evaluation of needs and how this informs allocation. The evidence highlights how the Irish PA system is distinct, in common with earlier evidence showing that the characteristics of PA schemes vary widely. This variation stretches across funding arrangements, needs assessment procedures, principles of provision, accountability requirements and the working conditions of the assistants [

5,

6]. The earlier phase provides a valuable backdrop to this primary research phase, where the voices of disabled people are the centre stage.

Centring the voices of disabled people and capturing their experiences is increasingly being widely recognised as fundamental in order to provide high quality services, though practice on this front may still lack the rhetoric. A long-awaited report on the costs of disability in Ireland, the

Costs of Disabilities report, was published by the Irish Government in 2021 [

7]. It lays out the financial impact of disability in Ireland, and there is a concerted effort on the part of disabled people and their advocacy groups to use the report to argue that the costs should not continue to fall on individuals on the grounds of justice. Significant developments in Irish PA are planned over the next few years to meet growing demand [

8], improve quality assurance [

9] and place PA supports on a statutory footing. This process has begun with home care for older people [

10] and whether it is implemented for PA supports as well is likely to depend on how that process goes. Ireland has an opportunity to build a much stronger PA system by making the system responsive to service user’s needs and values through these reforms. The Irish example could be particularly useful for other wealthy nations aiming to improve their existing systems, while the evidence of how PA can support people to live a full and independent life is relevant globally as countries grapple with implementing the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

For this research we use the term “disabled people” over “persons with disabilities” in line with advocates who see the term as emphasising the social model of disability. In this line of thinking, people with impairments are actively disabled by the socially constructed world they navigate rather than having the disability being individual and internal. However, we do not see the question as settled or our chosen term as the only correct one, only the most suitable in the present context. We acknowledge that many people prefer the term “persons with disabilities” and respect people’s right to use the language which they most identify with.

2. Theoretical Framework

In line with a number of international studies, most notably Mladenov’s work on PA user satisfaction [

5], our research is framed within an emancipatory research approach. As defined by Barnes [

11] (p. 122):

“Emancipatory research is about the demystification of the structures and processes which create disability, and the establishment of a workable dialogue between the research community and disabled people.”

As noted by Mladenov [

5], this approach incorporates several principles, including accountability to the community of disabled people, adherence to the social model of disability, making explicit the positionality of the researcher and generating practical outcomes which are useful for disabled people. The researchers have thus attempted to use their position within the research community to create research with, rather than on, disabled people. Neither author is disabled, and our position within the research community grants us a certain level of individual power and access to institutional prestige and other resources. Using these resources in a productive and ethically sound way has been a central concern in our work. Both of us have long experience of conducting research with marginalised groups, mostly within the field of education, focusing on not harming them in the process of the research or the dissemination of the results (an area where education research has often fallen short by engaging in deficit framing, theories rooted in biological or genetic hierarchies or the outright pathologisation of entire socioeconomic, cultural and ethnic groups) but instead aiming to improve their concrete conditions. To achieve this, we believe it is vital to include the voices of members of these groups in a meaningful, rather than tokenistic, way. From the outset, our study adhered to these principles; the study was undertaken in conjunction with disability advocates and disabled persons organisations (DPOs), with particular engagement on the study design and survey, in line with best practice [

12]. The study was oriented towards generating practical outcomes that would be useful for disability advocates, as well as for policymakers. Preliminary results have been disseminated among disability advocates and disabled persons organisations, and results will be available through key summaries in newsletters across a range of key stakeholder organisations.

Our theoretical framework is guided by the independent living movement which has been the driving force behind personal assistance provision in Ireland and internationally [

13]. At the heart of the independent living movement is the social model of disability, in which impairments become disabilities through collective and social, rather than individual and physiological, processes [

14]. Within the social model of disability, a person might be impaired by quadriplegia, for example, but they are disabled by lack of access to a suitable wheelchair, by the absence of ramps in key buildings or by prejudices around their impairment; in short, by the physically and culturally constructed environments they navigate in their day-to-day lives. The social model challenges us to consider the ways in which society fails to take account of, or provide for, people with impairments, and thus disables them, by highlighting the ways that many of the biggest barriers facing disabled people are artificial, although their impairments are not. Working from this model, the independent living movement is a movement of disabled people and their allies fighting for their right for an independent and full life in a world where architecture, technology and public services are designed for people with impairments, rather than inadvertently or purposefully disabling them.

The question of what a full and independent life actually looks like remains an open one, a long-term horizon beyond the immediate fight of the independent living movement to have more immediate priorities met. This study has tried to incorporate both levels of demand, to look at what PA service users need now and at what ideal a PA service would look like for them. It also remained sensitive to the conflation of meeting basic needs and facilitating independent living through the Irish PA system and the ways in which this fails to support, or actively undermines, disabled people’s self-determination. As the study progressed, the value of using Sen and Nussbaum’s capability approach [

15] as a lens through which to consider the PA system became clear. Scholars like Mitra [

16] and Terzi [

17] have explored how the capability approach can be adapted to disability studies, with particular emphasis on the role of society in promoting justice for disabled people. Coupled with this social conception of justice, the capability approach’s centring of each individual’s freedom to decide what is important to them, in terms of the functionings and capabilities they value, clearly mirrors the independent living movement’s assertion that effective supports should ensure that disabled people are in charge of the directions and day-to-day running of their own lives. The central position of authentic agency in the conception of justice within the capability approach also reflects the core thrust of the independent living movement’s goals. Building on this compatibility, the capability approach gives us a framework within which to evaluate the PA system as experienced by disabled people in Ireland. It also grounds the question in a universal standard of justice and highlights the role of the state and society in facilitating or obstructing justice.

One complication that PA presents to a capability approach is the inherently interpersonal nature of PA supports. Put simply, personal assistants are not just tools to be used but people themselves, with all of the potentialities and complexities people bring to every direct interaction. Foster and Handy [

18] and Trani et al. [

19] have used the concept of external capabilities to capture the way direct interactions between people can extend the capability set of one or both parties, a productive way to approach PA. Beyond the capability approach, however, this direct interaction has been the subject of nuanced critical attention, exploring the power relations between the service user as a disabled person and the personal assistant as a non-disabled person, but also between the service user as an employer and the personal assistant as an employee, and often a poorly paid and precarious one at that [

20,

21]. The professionalised support relationship at the heart of PA has been celebrated as an actuation of solidarity and mutual respect, but it has also been criticised as an inherently unequal relationship which tends towards condescension and sometimes leads to abuse and as another arena where disabled people must fight to be heard and taken seriously [

22].

Even the question of whether we should speak of PA as either a support role or a care role is contested, with the word “care” seen by some as inevitably carrying paternalistic connotations [

23] and by others as recognising all of our mutual interdependence and even providing a way to reorganise society around human wellbeing and social needs [

24]. As well as proposing a strong argument in favour of a wide-ranging conception of care, Lynch argues that the word’s negative connotations are inextricable from neoliberalism’s valorisation of individualism and economic self-interest. It is interesting, though, that support language is used more widely by disabled people’s organisations, suggesting that they have not, as yet, been convinced by these arguments. In the results and discussion we will return to the question of who is seen, by themselves and by others, as “cared for” rather than supported and explore how they understand and describe the relationship.

While this paper focuses on the voices, preferences and experiences of PA service users and not PAs, PA service users themselves raised many issues in relation to PAs; especially on the challenges of the relationship between the PA service user and the PA, but also on the conditions faced by PAs. Any consideration of the PA system and the experiences of those in receipt of PA services must therefore also include PAs. We will also return to this point in the discussion to highlight the need for future research to include their perspective as well.

Drawing on this framework, the paper is focused on four key research questions:

Are PA users satisfied with their personal assistance service in terms of the level and types of support they receive and the agency and autonomy they have in directing their personal assistance?

Are there structural forces resulting in different experiences for different users due to their location, the level of support they receive, the length of time they have been availing of PA or other factors?

What are the challenges that PA service users encounter in employing, using and benefitting from PA services?

What recommendations do PA service users have for changes and improvements to the PA system in Ireland?

Ultimately, as discussed above, the goal of this study is to identify key areas where the PA system can be improved in Ireland from the perspective of those actually receiving the PA services and highlight steps that could be taken to achieve this.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper reports on a cross-sectional mixed methods sequential explanatory design study [

25], namely a survey carried out with PA service users and follow-up in-depth interviews with a theoretical sample of survey respondents. Internationally, surveys with PA users have typically had relatively low response rates; our mixed methods research design was intended to capture both breadth and depth in understanding the lived experience of disabled people. There are few examples of large-scale representative studies of PA service users. One pan-European survey with disabled individuals that use PA supports gathered 60 responses, amounting to a 10 percent response rate [

5]. Another study with disability support service users at higher education institutions in the United States achieved a response rate of 15.4 percent (

n = 326) [

26]. Through engaging with service providers, DPOs and advocacy groups, as well as statutory bodies, our study sought to capture the experiences of a large and broadly representative sample of service users.

In line with our collaborative approach, disabled people in receipt of PA services were also included in the design of the survey, with several individuals giving invaluable direction on the issues covered in the survey and the phrasing of specific questions. In order to facilitate the inclusion of PA users with a range of impairments (including intellectual impairments), we adopted a multimode survey approach—providing options to complete the survey online (via Lime Survey), by post or telephone—as well as providing multiple survey options. Alongside the main survey, a second version of the survey was designed, focusing on fewer constructs of interest and using plainer language in order to be quicker and less demanding to complete (plain English and easy to read versions were provided). Further, all survey instruments were designed in consultation with ACE Communications, who specialise in tailoring instrument design to individuals with intellectual impairments.

As there is no national level database with accurate information on PA service users, respondents had to be recruited through service provider organisations. These service providers are generally non-profit organisations with a focus on specific regions or on specific impairments, though some are national and wide ranging in their remit. There are some for-profit organisations, as well as one organisation which acts as an umbrella group for PA service users who directly employ their PAs. Data from the HSE, a survey with HSE disability managers [

4], and data from the Disability Federation of Ireland (DFI) were used to identify the population of PA service providers. Identified service providers were asked to distribute the survey to all PA users who:

Are in receipt of personal assistant supports;

Are over the age of 18 at the time of the survey distribution;

Do not have moderate, severe or profound intellectual disabilities.

This decision was made after consultation with other stakeholders on the basis that the number of service users with “moderate, severe or profound intellectual disabilities” was thought to be low and their needs in relation to PA seen to be different those with “mild” or no intellectual disabilities. The language used here is that of the medical model rather than the social model—this was decided after consultation with stakeholders involved in PA provision regarding the language used by service providers and the HSE. It serves as a useful crystallisation of the difficulties of conducting research built on the social model of disability in a system driven largely by the logic of the medical model. In line with best practice [

5,

27], the research design was reviewed by the ESRI Research Ethics Committee to ensure the highest standards were upheld. The team included three ESRI staff members and one external expert. Ethical approval was awarded on 20 April 2021.

The survey covered issues under the headings of “Demographic, education and employment information”, “Disability and impairment type”, “Personal assistance supports, uses and experiences”, “Process of gaining access to personal assistance”, “Social support and quality of life” and “Views on personal assistance in Ireland”. It included closed and open response questions.

A total of 326 responses were received (274 in paper format and the remainder through online/telephone completion), representing approximately 20 percent of the population of service users to whom the survey was distributed. A range of descriptive and multivariate regression analyses were undertaken, in SPSS, to examine the factors and characteristics associated with different outcomes. These outcomes included the intensity of PA supports received, level of satisfaction with PA supports, life satisfaction levels and a desire for the reform of the PA system. Among the characteristics examined were age, gender, educational level, employment status, regional location, timing of receipt of supports (pre-2010 versus post-), complexity of need, nature of supports received, involvement in PA selection and the extent of social support available. Eight in-depth interviews were conducted based on the themes that emerged from the survey responses.

Table 1 below shows some key characteristics of the interviewees selected.

Thematic analysis was conducted on the open-ended survey responses and interviews to gather the respondents’ own words on key issues and highlight the nuances of individual experiences and areas of divergence across the sample. The challenge of creating a public model of PA, which is comprehensive enough to include all who need it but individualised enough to provide what each person accessing it needs, will be central to our discussion, and the results below will suggest some paths towards such a model.

4. Results

The results of the study speak for roughly 12–15 percent of the total population in receipt of HSE-funded PA services in Ireland in 2021, based on the number of PA service users reported by HSE key performance indicator (KPI) data from 2020. These data provide only the number of people in receipt of services and total number of hours.

Table 2 includes key demographic information about the respondents. Unfortunately, there are no population level statistics around the gender, age or types of impairments of those in receipt of PA services so we cannot assess the representativeness of the sample. It is possible, for example, that older respondents are better represented in the survey because there are more of them in receipt of PA services or because they are more likely to complete the survey. A population level database, which will record all of this information, the National Ability Supports System (NASS), is being assembled, but as yet, lacks widespread coverage of those in receipt of PA services [

4].

The quantitative and qualitative results of the study are here presented under five key headings covering the level and nature of PA support received by respondents, their satisfaction with the supports, their broader life satisfaction, their relationship with their personal assistant and their sentiments about reform of the PA system.

4.1. Level and Nature of PA Support

The levels of support received by respondents vary widely across the full sample. Overall, the median number of hours received per week is 10. In total, 31 percent of respondents are receiving 5 h or less of PA per week, 23 percent receive between 5.5 and 10 h, 24 percent receive 10.5 to 25 h, while 22 percent are receiving more than 25 h. A key research question in this study was whether there were structural factors leading to the different levels of support for different individuals with similar needs. Even within specific impairment types, the hours allocated vary widely with large standard deviations.

Descriptive results suggest statistically significantly higher PA allocations among those with higher levels of education, among those living in urban city areas and for those with lower levels of natural supports (those indicating that they do not have anyone they can count on if they have a serious personal problem). Regression models examined the factors and characteristics associated with lower and higher numbers of PA hours. The results show a variation in PA intensity across both geographic and social support indicators. People living in a city and those living in the capital city, Dublin, receive significantly more hours. Given funding cuts in the context of the period of austerity [

4], it is perhaps not surprising to find that those accessing supports prior to 2010 typically received greater levels of support. While it is not possible to establish the direction of causality given the cross-sectional nature of the data, the results show a relationship between levels of social or community support and levels of PA allocated. For example, respondents who indicate that they find it “hard or very hard to get help from a neighbour” are four times more likely to be in receipt of more than 15 h of PA support per week. Overall, more hours of assistance received from family is linked to a lower package of hours, while difficulty getting help from a neighbour is linked to a higher package of hours.

Within the qualitative data, more hours were widely called for across the open-ended survey questions, where it was the most common code recorded, and in most of the interviews. As can be seen in the examples in

Table 3 below, many of the responses in this code were just general calls for more hours, while some specified that they specifically wanted hours in the evenings and during weekends, and others highlighted specific things they wanted more hours to cover.

In terms of the nature of the supports received, and how disabled people use their PA services, support for personal care and activities of daily living are prominent, indicated by 71 and 79 percent of respondents. Assistance with social activities is indicated by just over half of respondents. Assistance in the workplace and assistance in education or training are less prevalent—with just 19 and 16 percent currently in receipt of these supports. As noted earlier, only a small minority of respondents are currently in employment (17 percent), with the majority unable to work due to illness/disability (55 percent) or unemployed (7 percent).

Two qualitative interviewees were selected because they were using PA supports for work, and both spoke about how vital these supports were to their ability to work full-time in professional/managerial positions. However, they also noted that securing these hours had been very difficult. One was operating a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy around the hours they were using for workplace support, as they felt that there might be issues with their service provider or the HSE if it was officially known that the hours were being used this way, while the other had been given extra hours to support them in working from home because they were going to be at home rather than because they were going to be working. Other interviewees and open-ended survey responses asserted that they were unable to get any workplace support hours and that this was a significant factor in preventing them from working, as outlined in some of the examples in

Table 4 below.

The nature of supports varied somewhat across respondents, with higher packages of hours generally allowing greater levels of support for personal care and activities of daily living. Using personal assistance services for personal care and daily activities was higher where people had lower levels of social or familial supports. For example, 63 percent of those with high levels of familial support (40 or more hours of non-paid assistance) were using personal assistance service support for daily activities, compared to 83 percent of those with lower levels of familial support. Assistance with social activities appears strongly related to the package of hours received—with greater hours enabling people to access support for social activities. In total, 65 percent of respondents receiving more than 15 h of PA support indicate some of this support is currently used to support social activities, while such support is indicated by just 44 percent of those with a lower package of hours.

Social support and support with activities were the most common specific supports identified in an open-ended survey question about extra supports respondents would like to have access to, with examples in

Table 4 above. Transport was also an area of concern for many respondents, with difficulty in accessing medical appointments, going shopping and getting out of the house reported, as well as travel more broadly to events like concerts and on holidays. In the interviews, it emerged that transportation issues were arising both from the current PA system and from wider social supports and opportunities for disabled people. Service provider policies around where personal assistants can bring PA service users and how they can travel there were pointed to by interviewees and survey respondents as limiting their ability to engage with the world outside their house. Issues around the number of hours were also raised in relation to the lack of time to travel somewhere, do something there and return home within the PA hours available. In addition, non-PA factors, such as the lack of accessible transport and the lack of a grant to acquire an appropriate vehicle or the capacity for the service user to divert funds away from other services like PA to do so were also issues. One interviewee living in a rural area outside a large town spoke of how they were able to use a municipal transport service to get to the town, but were unable to use it to commute to work due to its limited running schedule, while other bus services ran longer hours but were not accessible and there was no taxi in the area able to transport their wheelchair. As a result, the interviewee was unable to work despite wanting to do so and holding a post-graduate degree.

As well as these impacts on individuals, several open-ended survey responses and interviews highlighted the impact that inadequate supports could have on their families. Families (generally parents or partners) were often left to fill the gaps in support, putting relationships under strain and constraining these family members’ own capabilities in terms of time and energy to put to other valued ends. The prohibition on using PA funding to pay family members for care work was noted by several respondents as making their life more difficult. Again, non-PA supports, such as respite, were seen as vital to sustaining family support.

4.2. Satisfaction with Supports

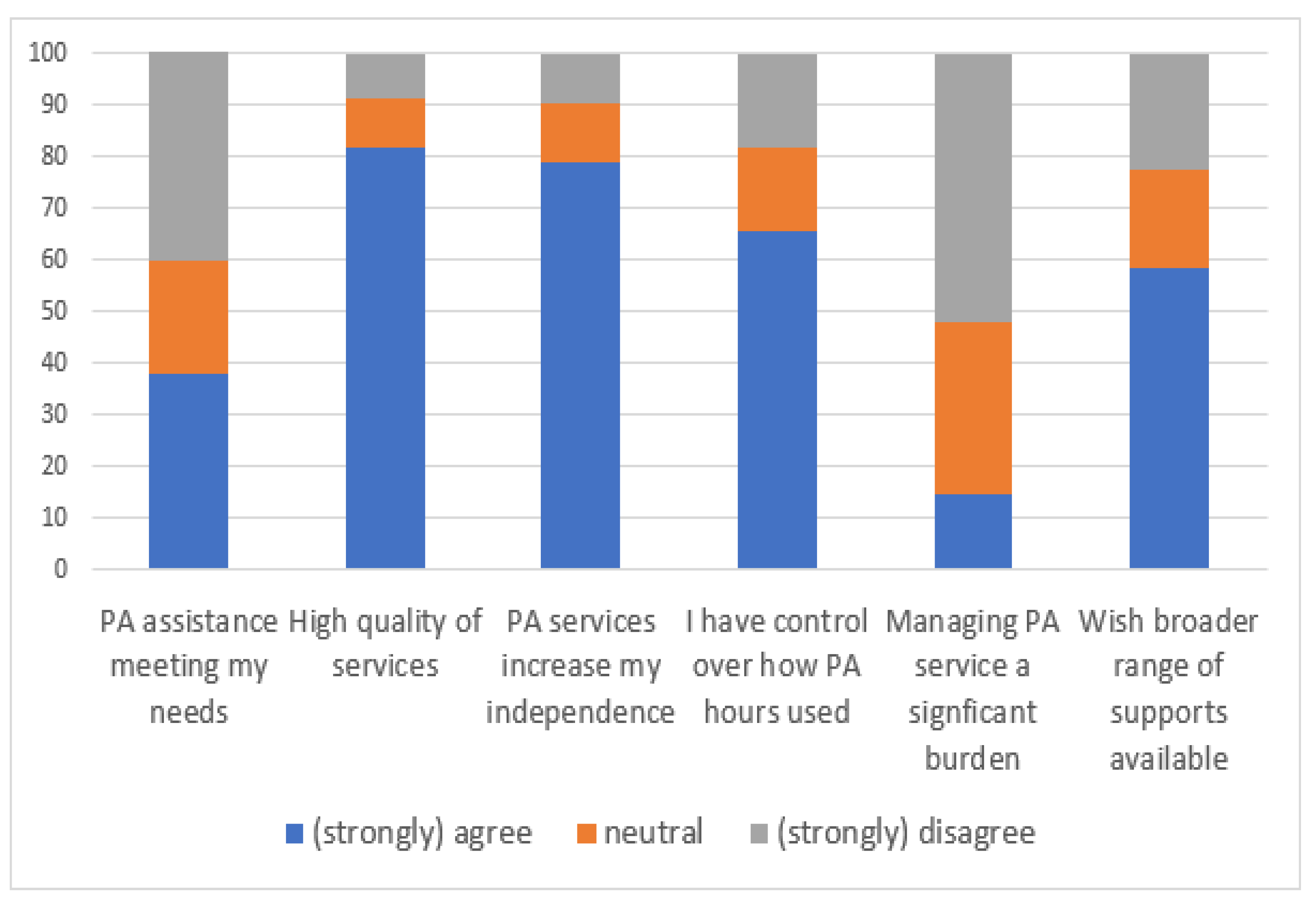

Respondents were asked to reflect on their personal assistance experiences, including the extent to which they agreed with statements around personal assistance services meeting their needs and whether personal assistance services increased their independence, thereby supporting their agency, with responses shown in

Figure 1 below. Overall, 40 percent of respondents disagree with the statement that their needs are being met by PA supports, while 38 percent agree. There is a clear relationship with age—with the percentage indicating that their needs are met increasing from 19 percent among 19- to 29-year-olds to 47 percent among those over 60 years. Almost four-in-five believe that the personal assistance services they currently receive increase their independence. That said, a majority (59 percent) wish a broader range of supports were available to them. Again, there is a clear gradient across age groups—with levels of agreement falling from 68 percent among the youngest cohort, to 45 percent among those over 60 years. Nearly two-thirds feel they have a high level of control over how the hours are used. The vast majority indicate that the quality of services they receive are of a high standard. While it is unclear how much service users exercise control over their service, just 15 percent indicate that managing their service (including governance and regulatory compliance) is a significant burden.

We find some geographic and demographic variation in the levels of satisfaction reported. Those over 60 years of age and those in Munster are more likely to agree that their needs are met. Those who are not satisfied with life and those who indicate they have no-one they can count on are more likely to disagree that their needs are met. Those involved in the selection of their PA are somewhat more satisfied that they have control over how their service hours are used. In terms of a desire for a broader range of supports, older respondents (aged 50–59 or over 60 years) and those living in the Leinster region are less likely to wish a broader range of supports are available. Interestingly, those using PA for social activities are less likely to wish a broader range of supports are available. Those with fewer people that they can count on (compared to six or more) are more likely to agree they would like a broader range of supports.

Combining responses on all six statements, we construct an overall measure of the level of satisfaction with PA services currently received. The scale variable combines the six statements, with two in the reverse order (“Managing my PA service is a significant burden” and “I wish a broader range of PA supports were available”) so the scale runs negative to positive. It has high reliability, with an alpha score of 0.74.

Table 5 displays the results of a logistic regression model examining predictors of higher levels of satisfaction, with significant variation across key characteristics evident. Overall, those aged 50–59 and over 60 years showed higher levels of satisfaction with PA services, perhaps reflecting earlier pre-austerity access to services, and hence, more comprehensive supports. The results suggest some geographic variations, with people living in Connacht/Ulster showing lower levels of satisfaction with PA services. The results suggest that respondents with more complex impairments (based on the number of conditions/difficulties indicated) are less satisfied with their services. Those receiving assistance with social activities show higher levels of satisfaction. Other models suggest that those who were not involved in their PA selection are less satisfied with their PA experiences, but this does not remain significant when we take account of the types of support received. Additional models examined predictors of satisfaction with each of the individual statements. Results suggest that those with weaker social supports are less likely to agree that the supports meet their needs.

As discussed in the previous section, significant dissatisfaction with the number of hours currently allocated to respondents, as well as with the constraints on when those hours could be used and what they could be used for, was expressed in the qualitative data. As well as this, the relationship with individual personal assistants figured prominently in how the respondents expressed satisfaction and dissatisfaction with PA more generally, something which we will return to in the next section. Issues with service user choice, control of their own PA and specific negative experiences were also raised within the qualitative data, if less commonly than issues with hours and around the PA relationship. It is clear from the examples in

Table 6, however, that these issues were of significant importance to those who raised them.

4.3. Quality of Life

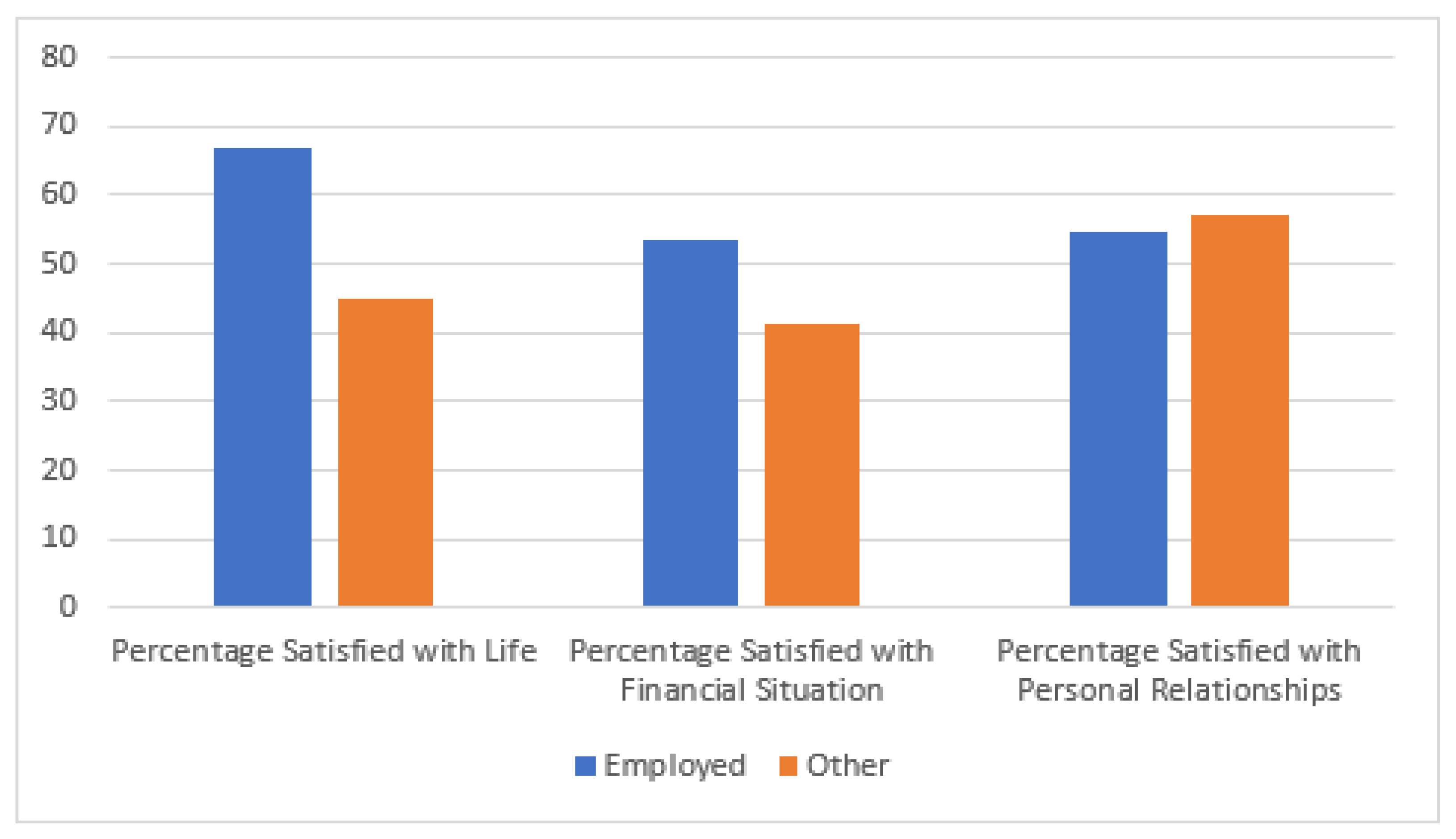

The survey included a number of questions on respondents’ overall life satisfaction, satisfaction with their financial situation and satisfaction with personal relationships. Females, those living in rural areas and those who completed higher education show higher levels of satisfaction with their personal relationships. As illustrated in

Figure 2, life satisfaction is substantially higher among those in employment, and this group are also more likely to be satisfied with their financial situation. Those who score highly on life satisfaction are also more likely to be receiving a higher package of PA hours.

Multivariate models assess the predictors of higher and lower life satisfaction levels. As shown in

Table 7, those aged over 60 years are more likely to indicate they are satisfied with their life. Those who indicated that they experienced multiple impairments were less likely to indicate they are satisfied with life compared to those who only reported one impairment, while those with fewer people they can count on are less likely to indicate they are satisfied with life. Compared to those unable to work due to illness/disability, those who are in employment are nearly three times more likely to score highly on the life satisfaction scale. Additional analyses (not shown) also show that those who would like a broader range of PA supports are less likely to score highly on the life satisfaction measure. Analyses again suggest that higher PA packages are associated with higher life satisfaction.

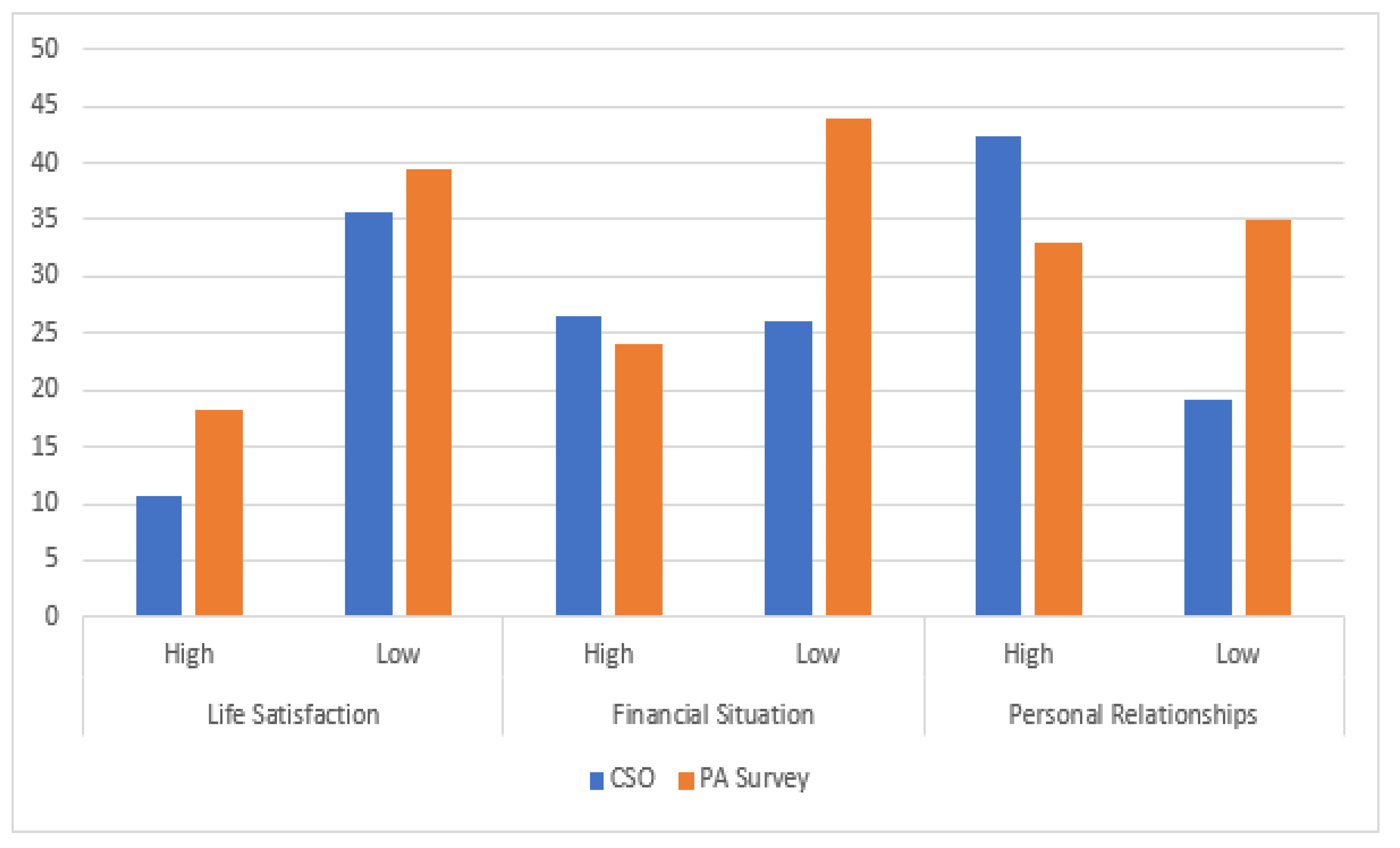

Using Irish Central Statistics Office data [

28], we can compare satisfaction among the respondents to this survey to that of the general population.

Figure 3, below, shows the proportions of each sample who rated their life satisfaction, financial situation and personal relationships as high (9–10) or low (0–5). In terms of life satisfaction, a greater proportion of the PA survey respondents were in both the high group (18 percent compared to 10 percent from CSO survey) and the low group (39 percent compared to 36 percent). PA survey respondents were much more likely to be in the low group in terms of financial satisfaction (44 percent vs. 26 percent) and personal relationships (35 percent vs. 19 percent), slightly less likely to be in the high group in terms of financial situation (24 percent vs. 26 percent) and substantially less likely to be in the high group in terms of personal relationships (33 percent vs. 42 percent).

These gaps are generally as one would expect, with the possible exception of the larger proportion of survey respondents than CSO respondents in the high life satisfaction group. The greater proportion of survey respondents in the low satisfaction group for financial situation and personal relationships highlights two areas where PA may be particularly weak, at present. The impact of insufficient PA on service users’ families, outlined in

Section 4.1, as well as the difficulty in using supports for the social purposes outlined in

Section 4.2 may explain some of the low satisfaction in personal relationships. The lack of PA support in the workplace, meanwhile, and the greater difficulty in finding employment as a result, is likely to increase the financial pressure on service users.

4.4. PA Relationship

The relationship between PA service users and their personal assistants was central to respondents’ day-to-day experiences of PA. Overall, however, 45 percent of respondents said that they were not involved at all in the selection of their PA, with 31 percent involved and 23 percent not involved in the selection but consulted in the final decision. Those who received PA supports pre-2010 were more likely to be involved in the decision than those who started receiving PA supports after 2010 (66 percent vs. 47 percent). Those involved in the selection were slightly more likely to agree that they have a high level of control over how PA hours are used: (72 percent vs. 59 percent). This lack of involvement runs counter to the emphasis placed on service user direction of their own services and on centring disabled people by both the independent living movement and the HSE’s own literature, as discussed in the theoretical framework section.

The qualitative evidence provides valuable insights into the dynamics of service users’ relationship with their PA(s). Comments around the PA relationship ranged from personal issues to structural issues, with the difficulty in finding and keeping high quality PAs highlighted.

Table 8 shows selected quotes around the key codes of PA relationship, PA quality, PA turnover, PA cover and PA conditions.

The above quotes speak to two distinct but interlocking challenges to personal assistance arising from the personal assistant relationship. The first is to do with the lack of choice perceived by many respondents in selecting their personal assistant and the resulting lack of rapport or chemistry. The second is to do with the challenges facing personal assistants themselves—chiefly the low pay and poor conditions in the short term and the lack of progression opportunities in the long term. Respondents and interviewees felt that these challenges contribute to difficulties in the service user-PA relationship by increasing turnover, causing stress in PAs and making it difficult to attract sufficient numbers of suitable applicants at all. Interviewees flagged the current labour market squeeze as causing acute difficulties in the autumn and winter of 2021, but pointed out that this was a case of a chronic issue boiling over, rather than something entirely new caused by the pandemic. These problems are by no means unique to PA; they exist across much of the field of “care” around the world. Tackling them, therefore, requires a structural change rather than PA-specific reform.

The emphasis on the importance of the personal relationship with the PA return us to the question of whether PA is best understood as support or care. The support aspects, in relation to professionalism, ability and willingness to follow directions and respect service user’s autonomy were central to some participants’ appraisal of PA. For others, however, the aspects which are closer to care, in terms of the warmth of the relationship and the PA “taking charge” while present were key strengths of PA. Some interviewees even discussed the reciprocity of the caring aspects of the relationship as a mixed but overall positive feature, as they found themselves involved in their PA’s wider lives. This may be an area where service user wishes diverge, and what one would consider excellent PA, another would find overbearing or aloof.

4.5. Recommendations for the Future of PA Provision

The survey asked respondents to reflect on a series of statements relating to PA provision in Ireland (

Figure 4). The evidence suggests an appetite for reform and improvements in the level and nature of PA provision. While just one-third agreed that PA services are improving over time, nearly three-quarters indicate that the system needs reform. A total of 68 percent feel that establishing statutory/legal rights to PA would have a positive impact, while 64 percent agree there is a need to increase regulation of provision. Overall, respondents were generally satisfied with the standard of service in Ireland, with 65 percent indicating high standards, but 79 percent reporting that they would like to see a minimum training level/qualification for PAs.

We constructed a scale measuring the extent to which respondents agreed with four statements concerning a need for reform of PA services. The four statements were “PA services available in Ireland are under increasing pressure over time”, “The PA service system is in need of reform”, “Establishing statutory rights to PA would have a positive impact on PA provision” and “There is a need to increase regulation of the provision of PA services”. The scale is reliable, with an alpha score of 0.74. A logistic regression model was used to explore variation in views in relation to the PA system and the need for reform. As shown in

Table 9, older cohorts are less likely to feel there is a need for reform of PA provision. Those residing in urban town areas are more likely to seek reform, as are those currently in employment. Those who did not have any involvement in the selection of their PA are more likely to look for reform, as are those with weaker social supports.

The qualitative evidence gives a rich insight into what sort of changes respondents and interviewees would like to see. Calls for greater breadth and depth of supports were common—for more hours, more types of support and greater funding in general as well as for better links to non-PA supports, all echoing what has been covered in previous sections. Suggestions around personal assistants were also prevalent, again largely focused on the issues discussed in the previous section. There were also suggestions that more fundamental systemic change was needed, in the form of greater service user input and direction, and so was a rights-based model of PA, distinguishing PA hours from home care hours and increasing access to personalised budgets. The systems surrounding PA were also remarked upon, especially in the form of calls for a channel for feedback to service providers, the HSE or an independent body as well as suggestions around auditing and monitoring the quality of PA services, PA service providers and personal assistants. These suggestions around auditing presented different, sometimes diametrically opposed, sentiments—some favoured greater auditing, backed by a body like the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA), while others felt such an approach was inappropriate for a service largely based in people’s homes. At present, the focus of regulation and inspection is social care locations, and it appears that respondents are concerned that the same approach would be taken with PA. The planned model of regulation for home care in Ireland would focus on regulating providers rather than carrying out inspections in people’s homes, and this research suggests the same approach should be taken for PA. Further consultation with service users and clear communication about what it would and would not involve will also be vital to the success of any such regulation.

Table 10 presents a selection of quotes around these points.

Also featuring strongly in the suggestions for reform were calls to make PA easier to access in the first place, both through making more information about it available for people who might be eligible and through improving the assessment and allocation process. In particular, the wait times for assessment and allocation and the sense that certain types of impairment and people in particular circumstances slipped through the gaps when it came to allocation were highlighted, as shown in

Table 11. One interviewee drew attention to the difficulties they had experienced in trying to access services in their sixties—they argued forcefully that the current age limit of 65 years or younger was entirely arbitrary and did not take into account their capacity to direct their own PA rather than receiving a more prescriptive home support package. Another interviewee was unable to access any services at all, and described their frustration in trying to get an assessment and the allocation of hours for which they felt they were eligible and in need of in order to achieve a decent quality of life:

“I have four main conditions that make me very weak … so it has to be a wheelchair from outside the front door … and I’m just not old enough for care, they don’t put all the conditions in a bag, they just say one, two, three no none of those qualify … they have a checklist, they look at me and they say I don’t qualify … An hour, three times a week, that would be life-changing … having a wash … tidying, making the house a bit more accessible … taking me to a shop … it would be a game-changer … just having a person coming in and saying ‘what do you need?’”.

As this project focused predominantly on those in receipt of supports, the experiences of those currently not accessing any are not covered in as much detail, but it must be noted that there are people in this category, and that there will continue to be until the funded hours available in each region are brought in line with existing met and unmet needs [

4].

Overall, the findings discussed in this section show that there is a significant demand for reform among participants in this research. We will now turn to potential reforms which should be considered within the context of the Irish PA system.

5. Discussion

Personal assistance in Ireland exists under severe fiscal pressure, with the funding earmarked for PA predetermined by HSE budgets rather than based on the existing need in each region [

4]. This zero-sum system (a legacy of the 2008 financial crash and the subsequent imposition of austerity), in which an extra hour for one service user is one fewer hour for another, explains why there is a gap in hours received between those who started accessing PA before roughly 2010 and those who started after. As new hours become available much more slowly than the growth of unmet need, these larger packages of hours are often carved up when the person using them leaves the system, either to a different setting, a different area or through death. In this context, the calls for more hours and a broader range of supports, which were the most widely expressed suggestion for reform among participants of this study, are clearly also calls for adequate funding of PA. Considered through a capability framework, the qualitative evidence suggests that the lack of such funding has a detrimental effect on functionings and thus on the capabilities valued by participants in relation to their ability to participate in activities that many of us take for granted, such as shopping, going to the cinema, working and much more. The capability framework asks us to go further than recognise this detrimental effect—we must consider it an injustice arising from how resources are distributed in society, and especially from political decisions around whose needs will be met and whose will not.

While the increased hours called for by participants in this research would require a substantial increase in funding, the current level of expenditure on PA is a small fraction of the state’s spending on disability services: PA together with home support services constituted 5% of disability spending in 2018, with a budget of EUR 80 million [

29]. The overall disability services budget was EUR 1.86 billion in 2018, from a total health budget of EUR 15.46 billion. There is also space for other potential reforms which would not be as costly and thus could be implemented much more quickly and somewhat more straightforwardly. Standardising how PA is allocated across the country and drawing up best practice guidelines for putting service users in charge of their own PA are vital steps to ensuring that PA services meet the HSE’s own definition rather than being something closer to personal care or home support. Putting in place channels for service users to provide feedback and report problems without fear of retaliation is also vital in ensuring that services are performing as they are intended to. More generally, the question of how to ensure services are performing as they are supposed to is a contested one among the participants of this study. Some form of audit process was called for by many participants, but others raised questions about the appropriateness of these auditors entering service users’ homes. As increasing sums of public money are spent on PA, and HIQA call for the regulation of home care as part of the continuing reforms of and expansion of the sector [

9], some form of independent audit process appears inevitable; it is vital that service users are meaningfully involved in the design and implementation of this process.

This study also suggests that, from the perspective of PA service users at least, a vital step towards improving the PA system is improving the conditions for PAs. As long as the personal assistant position involves relatively low pay, poor conditions and no prospect of progression it will be difficult to attract and retain qualified and high-performing staff, especially with what looks likely to be a tighter labour market for the next few years. As with increasing hours, steps like paying personal assistants a living wage and including travel time in their hours, rather than just hours of PA provided, would require substantial funding increases.

Beyond PA, the qualitative material, in particular, suggests the potential of other supports in promoting independent living. The importance of peer networks to those interviewees who were involved (mainly through engagement with DPOs) was one area of particular note. Some of the interviewees who were not engaged in such networks emphasised difficulties in areas such as knowing what supports exist and how to access them and dealing with loneliness and feelings of helplessness. The potential of peer networks and DPOs in supporting people with these issues is clear. No doubt there are a range of other ways that peer networks could be encouraged, and a range of other supports which could be of great use in the Irish context, and future work should look beyond the PA system at ways to support independent living. The consciousness-raising element of the independent living movement in empowering disabled people to articulate and fight for their rights may be best galvanized by such other supports, though the PA system itself leaves room for improvement on this front. In particular, the emphasis on funding service providers to provide PA hours, rather than funding service users to organise their own PA, restrains disabled people’s self-determination. Developments in this front are ongoing [

4], but it is clear Ireland has a long way to go before it meets the true definition of PA as a user-directed support.