The Impact of Stroke on the Quality of Life (QOL) of Stroke Survivors in the Southeast (SE) Communities of Nigeria: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. IPA

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Data Collection Methods

2.4. The Study Population and Recruitment

2.5. IPA Analysis

3. Summary Results

4. Thematic Results and Discussion

4.1. Master Theme 1: An Unfamiliar Self

4.1.1. Introduction

4.1.2. Disempowerment (Physically and Psychologically)

‘Then suddenly, noticed my leg and arm become very heavy and my mouth started twisting, that’s all I could remember’.(Emeka, 54 years old)

‘it becomes so …soft, my mouth started to twist …just like this….so, I couldn’t walk again, even…on the chair, I was sitting….i almost fell off’.(Ouchi, 62 years old)

‘they took me to the hospital. On my get there, I could not get down from the vehicle again’.(Amaka, 53 years old)

‘I’m not going anywhere any more since my attack’.(Bisi, 29 years old)

‘I was going out before, but since I have not been well, I have just been at home’.(Amaka, 53 years old)

‘I am feeling sad that there is no one that I am going to see again, I’m feeling sad like a person’.(Tobichi, 58 years old)

‘or have an idea of what is happening around me’.(Meka, 58 years old)

‘it dawned on me that this was serious because there is no other way…’.( Meka, 58 years old)

‘and I couldn’t leave my bed again, at all (that was all I knew) …’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘I said no, and they agreed and brought a chair, errm stretcher and helped me to the stretcher…’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘I could not drive again …so I parked my car…’.(Emeka, 52 years old)

‘when somebody wake up, you cannot have anything to feed their children will lead you to thinking…’.

4.1.3. Self-Identification

‘there is nothing I am doing, just stay home and do my exercises’.(Joko, 61 years old)

‘it is because of the stroke I had that is why I am a lot more inactive. I no longer go to places I use to go or enjoy the things I use to enjoy before. I no longer have the freedom I had before …erm this has changed my life due to the stroke. I can no longer do the things that I use to do, that I was good at’.(Enosi, 55 years old)

‘those places I can’t attend, have to do without me as I can only do what I can considering my situation’.(Tobichi, 58 years old)

‘The main limitation is the ability to be active and to go to funerals and burials like I use to before’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘when I get better, I can start going out’.(Amaka, 53 years old)

4.1.4. Physical Disability

‘yeah, it has changed me, because before the stroke, I use to cook in my house, but now I cannot without help. Now I need support to cook’.(Amaka, 53 years old)

‘I was going, as I wanted to climb the stairs, but I fell on the floor’.(Meka, 58 years old)

‘I started limping on the leg, so I went to seek help’.(Meka, 58 years old)

‘I could not move at all from the bed or use my legs to the private toilet’.(Emeka, 54 years old)

‘Then I suddenly, noticed my leg and arm become stiff and heavy’.(Emeka, 54 years old)

‘at times I don’t even know or have an idea of what was happening around me, I later tried to move with energy, I couldn’t walk. I no longer feel myself it just psychosocial’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

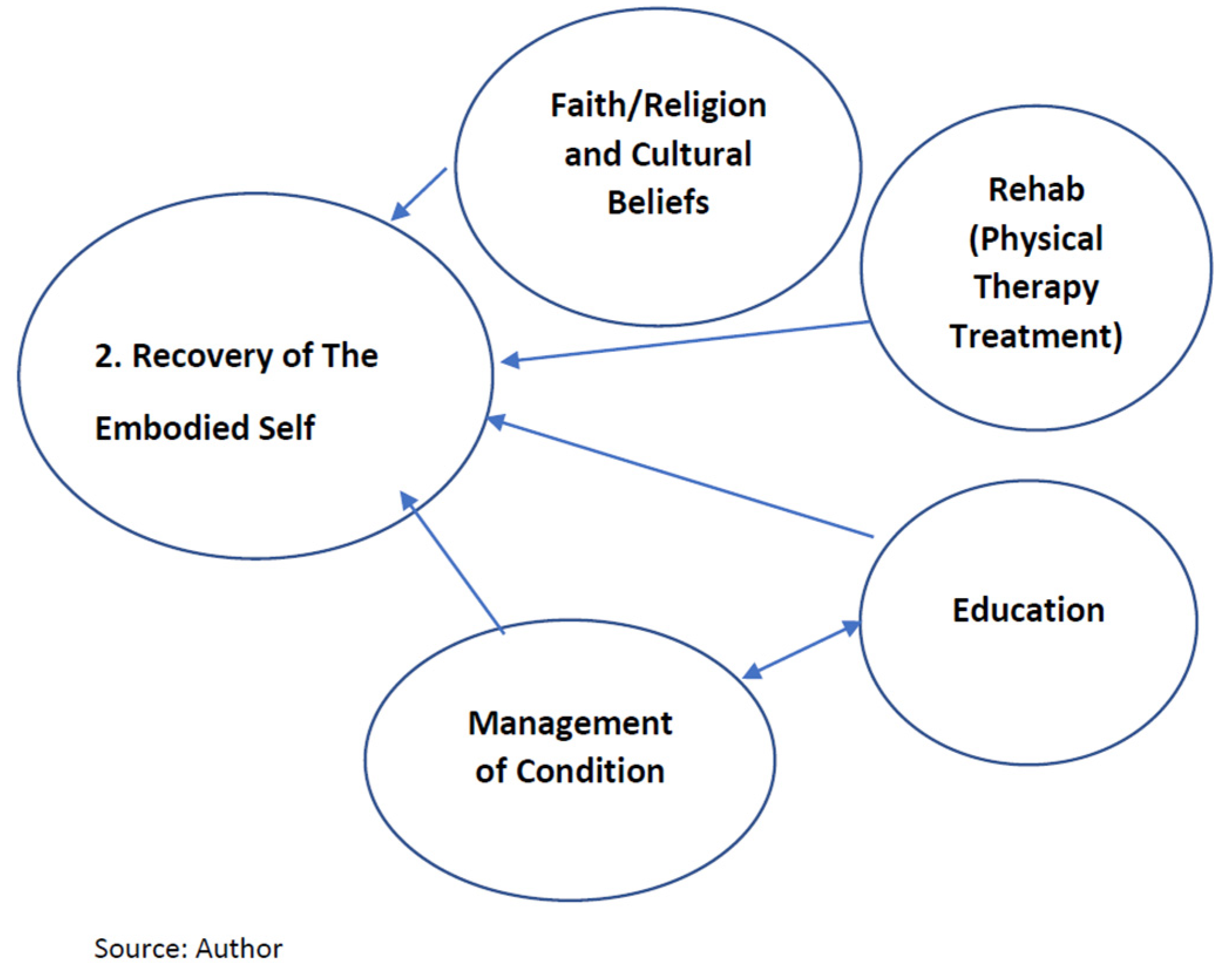

4.2. Master Theme 2: Recovering of the Embodied Self (Transitional Stage)

4.2.1. Introduction

‘I believe my arm will raise up, because before I was not raising it, because before… errh the only thing was the finger, but I am using it little by little. I can now straighten it up to hold something’.(Emeka, 54 years old)

‘They say it did not touch my bones, it was only soft tissue ie my muscles and nerves’.(Meka, 58 years old)

‘Yes, I don’t exercise for one week, I start to feel bad, exercise is very good for stroke’.(Amaka, 53 years old)

‘I have started to get up, I can now stand and sit’.(Tobichi, 58 years old)

‘The exercises have helped me a great deal…. A great deal’.(Enosi, 55 years old)

‘It helped me a bit, but not ready to stand up and walk’.(Tobichi, 58 years old)

4.2.2. Education

‘I know now, I must stop thinking, there is noting that will annoy me anymore, what I know now is that I will manage being upset’.(Joko, 60 years old)

‘Your diet matters a lot, some people do no eat right’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘I avoid anything that has too much oil in it, we are advised to watch what we eat eg avoid high cholesterol’.(Emeka, 54 years old)

‘Its HBP and Diabetics, that mainly lead to stroke, but I’m not a diabetic and I don’t think I was hypertensive’.(Bisi, 29 years old)

‘I still have more… relief since that day till now, the things I didn’t know, now I know’.(Meka, 58 years old)

4.2.3. Management of the Condition

‘I suffer from HBP, now I often take my medication. But prior to the stroke I had not taken my medication for a week and some days’.(Enosi, 55 years old)

‘Everything before now, my BP was very high and the nurses and doctors tried to bring it down’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘Because I am now taking my meds regularly and checking my BP and sugar levels as I do not want my BP to be more than 100 over something. You know they explain all these things to you to better manage the condition’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘I’m advising everyone that are at risk of stroke to go for regular health check-up, stabilise your BP…. Go to for you physiotherapy and do not waste time’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘I will be checking my BP often and try to keep my weight down’.(Jopadi, 64 years old)

‘Now that I have had stroke, I will advise anyone who do not have stroke that they should be careful with their health, they should regularly go for BP check-up if they are at risk as this condition is not a joke. Checking BP regularly so they do not fall into this type of condition’.(Jopadi, 64 years old)

4.2.4. Spirituality

‘calling God to help us …only body that can help us is God. Is only God can do anything that you want in your life…’.

‘With God anything can be possible just living by the help of other people now, without my junior brother, I don’t think how far I would have gone by now because he helped me a lot and he took me to many places to make sure I got better. So, I’m thanking God for that’.

Buchi, Emeka, Joke and Bisi stated the following:

‘Yeah…herbal medicine. Yeah, they used razor blades to cut my arms and gave me some medicine…’.(Buchi, 72 years old)

‘He gave me some medicine because I was not walking before, then I started walking slowly …’.(Emeka, 54 years old)

‘He used the medicine and he gave me the medicine and I drank it. It get some massage he gave me using some things and hot water to my legs…’.(Joke, 61 years old)

‘Because when I got there, there were people that it was serious issues that are treated and got better, there were people it was very serious for them and they are getting better there…’.(Joke, 61 years old)

‘It helped me sha, in the sense that my hands was in a fist form before, but after taking the TM it stretched out a little…’.(Bisi, 29 years old)

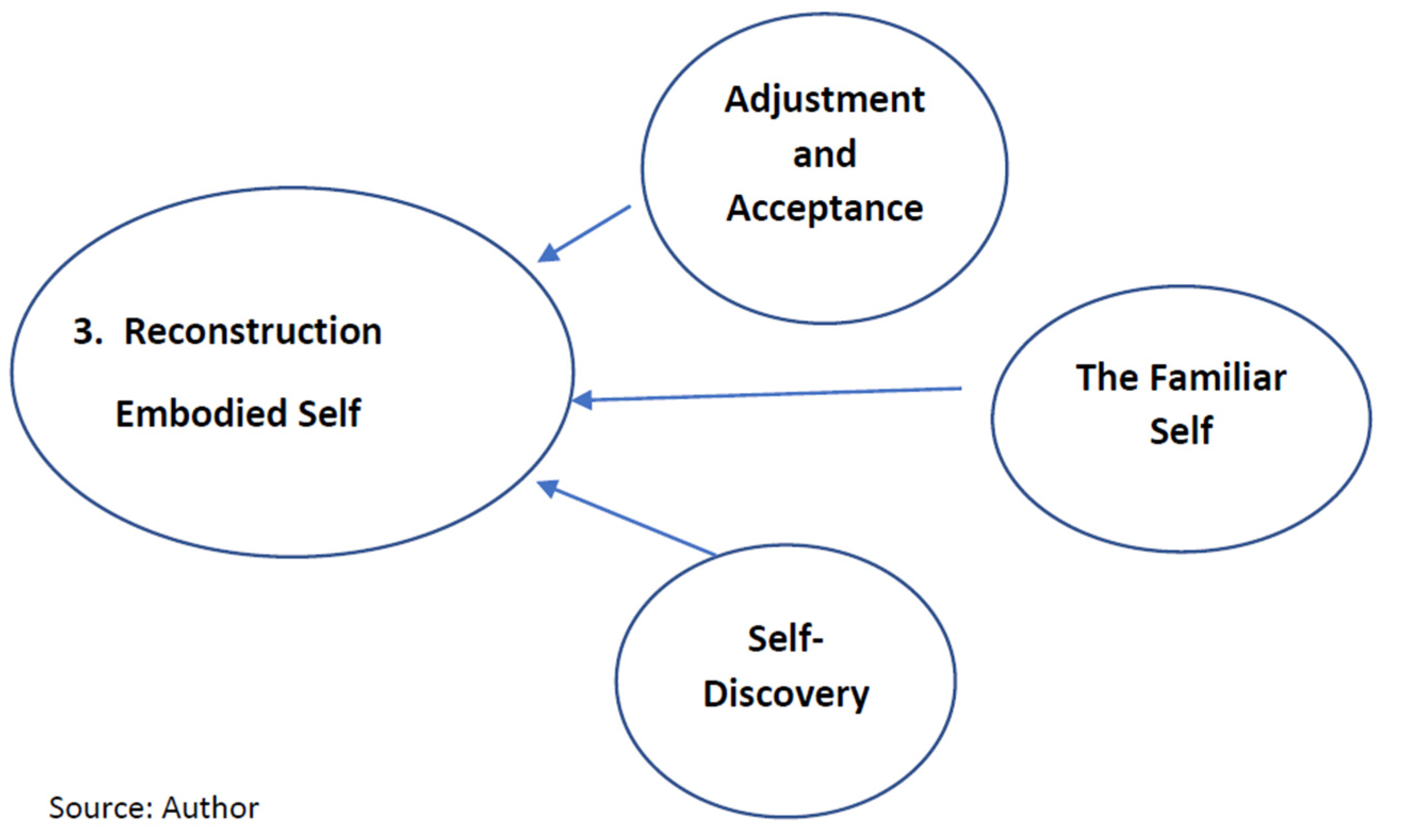

4.3. Master Theme 3: Reconstruction of the Embodied Self

4.3.1. Introduction

4.3.2. The Familiar Self

‘But now I walk slightly independently, sometimes with a walking aid but hope soon to walk without any help or aid… so to me this is a big achievement’.(Enosi, 55 years old)

‘It’s getting better …its becoming better’.(Enosi, 55 years old)

4.3.3. Self-Discovery

‘After doing a lot of exercises, I have more strength than before… errh, this has helped me a lot to get to this level in my recovery’.

‘When I first came to the rehab club, I saw some people who had worse conditions than myself, I just knew I was going to get better’.

4.3.4. Acceptance and Adjustment

‘During the sessions I do, I do it with all my ability and strength and I feel I am doing a good job because of all the improvements I have made in my recovery. I feel confident that with time, things will be a lot better for me’.(Bisi, 29 years old)

‘I’m coping with the assistance of my wife and brother taking care of me’.(Emeka, 54 years old)

‘The experiences I have now, is that I can’t do those things I used to do easily’.

5. Conclusions

Implications for Practice

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badaru, U.M.; Ogwumike, O.O.; Adeniyi, A.F. Quality of life of Nigerian stroke survivors and its determinants. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2015, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent-Onabajo, G.; Mohammad, Z. Preferred rehabilitation setting among stroke survivors in Nigeria and associated personal factors. Afr. J. Disabil. 2018, 7, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinpelu, A.D.; Gbiri, C.O. Quality of life of stroke survivors and apparently healthy individuals in south-western Nigeria. Physiother. Ther. Pract. 2009, 25, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Lawes, C.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Anderson, C.S. Stroke epidemiology: A review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol. 2003, 2, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolabi, M.O. Consistent determinants of post-stroke health related quality of life across diverse cultures: Berlin-Ibadan Study. Neurologica 2013, 128, 287–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enwereji, K.O.; Nwosu, M.C.; Ogunniyi, A.; Nwani, P.O.; Asomugha, A.L.; Enwereji, E.E. Epidemiology of stroke in a rural community in Southeastern Nigeria. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2014, 10, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezejimofor, M.C.; Fuchen, Y.; Kandala, N.; Ezejimofor, B.C.; Ezeabasil, A.C.; Stranges, S.; Uthman, O.A. Stroke survivors in low and middle-income countries. A meta-analysis of prevalence a secular trend. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 364, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.M.; Al-Sadat, N.; Loh, S.Y.; Jahan, N.K. Predictors of post stroke. Health-Related quality of life in Nigerian Stroke survivors: A 1-year Follow-up study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 350281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A. Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2004, 1, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. Br. J. Pain 2015, 9, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, E.; Wright, G. The difficulties of learning object oriented. Analysis and design: An exploratory study. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2002, 42, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P. Qualitative Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, L. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Johnson, R.B.; Collins, K.M. Call for mixed analysis: A philosophical framework for combining qualitative and quantitative approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2009, 3, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeechan, J.G. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of living with colorectal cancer as a chronic illness. JCN 2018, 27, 3148–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katerndahl, D. Impact of spiritual symptoms and their interactions on health services and life satisfaction. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timothy, E.K.; Graham, F.P. Transitions in the Embodied Experience after stroke: Grounded theory study. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzmüller, G.; Asplund, K.; Häggström, T. The long-term experience of family life after stroke. Am. Assoc. Neurosci. Nurses 2012, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luker, J.; Lynch, E.; Bernhardsson, S. Stroke survivors experience of physical rehabilitation: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1698–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omu, O.; Reynolds, F. Health professionals’ perceptions of cultural influences on stroke experiences and rehabilitation in Kuwait. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 34, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Northcott, S.; Moss, B.; Harrison, K.; Hilari, K.A. A systematic review of the impact of stroke on social support and social networks: Associated factors and patterns of chang. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, S. Stroke disability and rehabilitation of stroke: World health Organisation perspective. Int. J. Stroke 2013, 8, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntzen, C.; Borg, T.; Hamran, T. Long-term recovery trajectory after stroke: An ongoing negotiation between body, participation and self. Disbil. Rehabil. 2014, 37, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowswell, G.; Lawler, J. Investigating recovery from stroke: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2000, 9, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owolabi, M.O. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures: There are still many unanswered questions about human life. Sci. World J. 2008, 8, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.G.; Anke, A.; Aadal, L. Experiences of quality of life the first year after stroke in Denmark and Norway. A qualitative analysis. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Wellbeing 2019, 14, 1659540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, C.; Coen, R.F.; Kidd, N. A qualitative study of the experience of psychological distress post-stroke. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2572–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peoples, H.; Satinr, T. Stroke survivors’ experiences of rehabilitation: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 18, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roding, J.; Lindstrom, B. Frustrated and invisible—Younger stroke patients experience of the rehabilitation process. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajatovic, M.; Tatsuoka, C. A Targeted self-management approach for reducing stroke risk factors in African American men who have had a stroke or transient ischemic attack. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 32, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.B.; Kleindorfer, A. Stroke in a biracial population: The excess burden of stroke among blacks. Stroke 2004, 35, 426–431. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J.G.; Bakris, G.L.; Epstein, M.; Ferdinand, K.C.; Ferrario, C.; Flack, J.M.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, W.E.; Haywood, J.; Maxey, R.; et al. Management of high blood pressure in African Americans. Consensus statement of the Hypertension in African Americans Working Group of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks. Arch. Int. Med. 2003, 163, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosarelli, P. Medicine, Spirituality, Patient Care. JAMA 2008, 300, 836–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.L.; Peters, R.; Schim, S.M. Spirituality and spiritual Self-care. Expanding and Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory. Nurs. Sci. Qual. 2011, 24, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Health Systems: Improving Performance; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Parappilly, B.P.; Mortenson, W.B.; Field, T.S.; Eng, J.J. Exploring perceptions of stroke survivors and caregivers about secondary prevention: Longitudinal qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akosile, C.; Adegoke, B.; Ezeife, C.; Maruf, F.D.; Ibikunle, P.O.; Johnson, O.S.; Ihudiebube-Splendor, C.; Dada, O.O. Quality of life and sex–differences in a South–Eastern Nigeria Stoke sample. Afr. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, S.A.; Isezuo, S.A. Health related QOL of stroke survivors: Experiences of a stroke unit. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2012, 1, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Sampane-Donkor, E. A Study of Stroke in Southern Ghana. Epidemiology, Quality of Life and Community Perceptions. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Health Sciences, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent-Onabajo, G.O.; Muhammad, M.M.; Usman Ali, M. Social support after stroke: Influence of source of support on stroke survivor’s health-related quality of life. Int. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. J. 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, C. Introducing Qualitative Research in Psychology; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Study ID | Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Type of Stroke | Year of Stroke | Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Buchi | 72 | Male | Ischemic | 2018 | 6 |

| Participant 2 | Emeka | 54 | Male | Haemorrhage | 2019 | 4 |

| Participant 3 | Amaka | 53 | Female | Haemorrhage | 2012 | 4 |

| Participant 4 | Meka | 60 | Male | Ischemic | 2017 | 5 |

| Participant 5 | Ouchi | 62 | Male | Ischemic | 2018 | 5 |

| Participant 6 | Enosi | 55 | Male | Haemorrhage | 2018 | 4 |

| Participant 7 | Bisi | 29 | Female | Haemorrhage | 2015 | 1 |

| Participant 8 | Joko | 60 | Female | Ischemic | 2015 | 7 |

| Participant 9 | Jopadi | 64 | Female | Ischemic | 2015 | 5 |

| Participant 10 | Tobichi | 58 | male | Haemorrhage | 2018 | 0 |

| Master Themes | Superordinate/Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Unpredictable Body | |

| Self-identity Disempowerment: Physical and psychological Physical Disability |

| Transitional Stage | |

| Rehabilitation /Physical Therapy Treatment Education/Management of Condition Faith/Religion and Cultural Beliefs |

| My New Life after Stroke | |

| Familiar Self Self-discovery Adjustment and Acceptance |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adigwe, G.A.; Tribe, R.; Alloh, F.; Smith, P. The Impact of Stroke on the Quality of Life (QOL) of Stroke Survivors in the Southeast (SE) Communities of Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. Disabilities 2022, 2, 501-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030036

Adigwe GA, Tribe R, Alloh F, Smith P. The Impact of Stroke on the Quality of Life (QOL) of Stroke Survivors in the Southeast (SE) Communities of Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. Disabilities. 2022; 2(3):501-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdigwe, Gloria Ada, Rachel Tribe, Folashade Alloh, and Patricia Smith. 2022. "The Impact of Stroke on the Quality of Life (QOL) of Stroke Survivors in the Southeast (SE) Communities of Nigeria: A Qualitative Study" Disabilities 2, no. 3: 501-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030036

APA StyleAdigwe, G. A., Tribe, R., Alloh, F., & Smith, P. (2022). The Impact of Stroke on the Quality of Life (QOL) of Stroke Survivors in the Southeast (SE) Communities of Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. Disabilities, 2(3), 501-515. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030036