A Scoping Review of Empirical Literature on People with Intellectual Disability in Nigeria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Research Question and Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

- identification of the research question;

- identification of relevant studies;

- selection of studies to be included;

- charting the data;

- collating, summarising and reporting the results of the articles included for review.

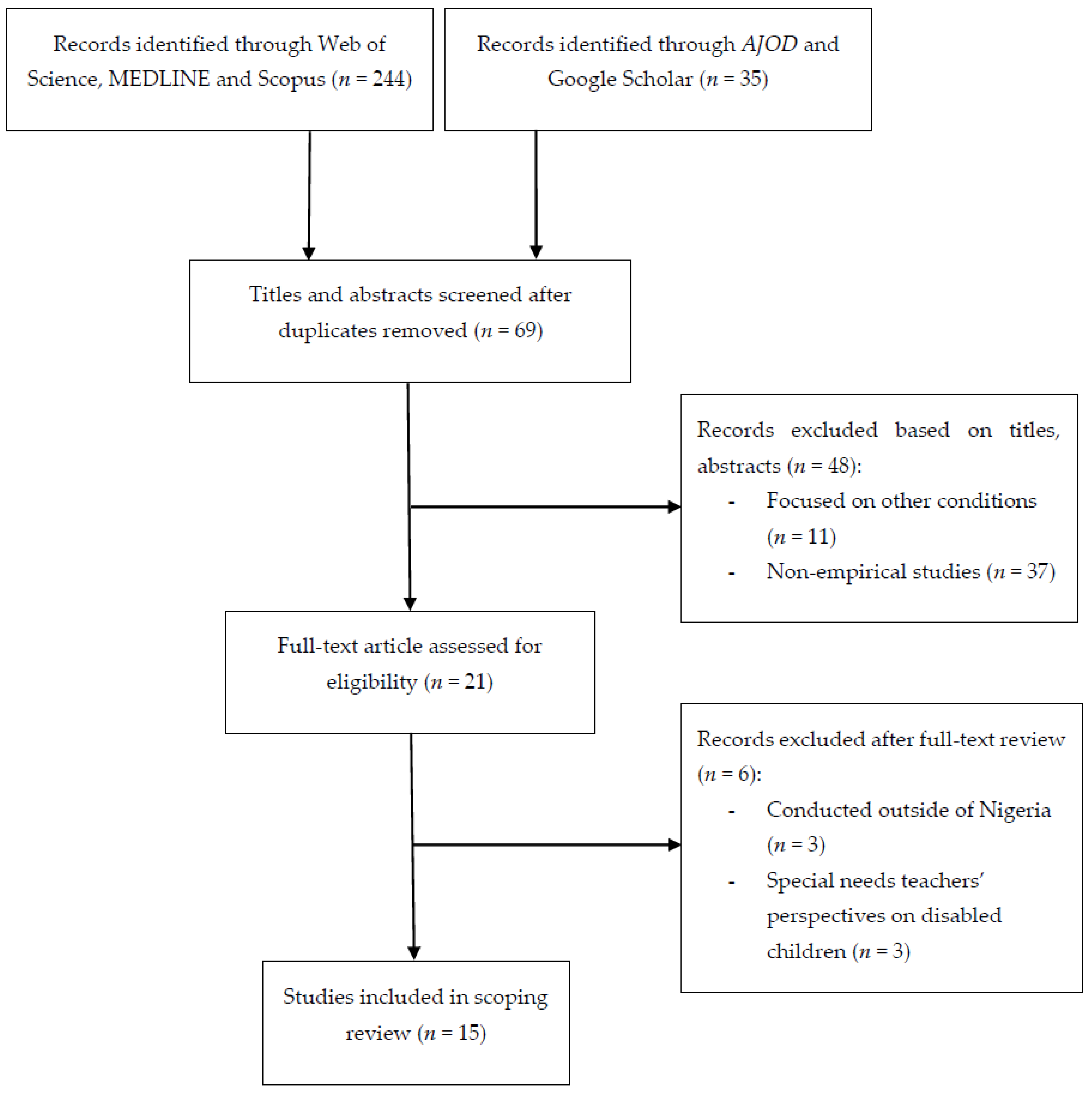

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies—Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of Studies—Applying Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

- Study—peer-reviewed articles reporting on empirical studies, qualitative or quantitative and/or mixed method research;

- Population—include people with ID alone or with a comparison group or people with ID and their families and teachers as research participants or solely include parents and siblings of people with ID;

- Language and year—written in the English language and published between January 2007 and March 2021. The year 2007 was selected because that was the year when Nigeria ratified the UNCRPD, and the subsequent years potentially covered disability-related policy changes in Nigeria that may have impacted the lives of people with disabilities. Additionally, a review carried out by Ngenga [2] of previous years yielded only 3 empirical research articles on ID in Africa: 1 was from Nigeria and 2 from South Africa.

2.5. Exclusion

- Nonempirical papers;

- articles not reporting data specifically identifying the lived experiences of people with ID or their families and teachers;

- Grey literature was excluded—prior to deciding to exclude the grey literature, the keywords presented in Table 1 were used to search three grey databases (i.e., www.opengrey.eu; www.isrctn.com, accessed on 5 February 2021, as well as the World Health Organization database via the African Index Medicus), and the searches yielded no relevant results in the context of ID research in Nigeria.

2.6. Charting the Data

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics—Description of the Articles Included

3.2. Themes

3.3. Theme I: Caregiving Experiences

3.3.1. Interpersonal and Emotional Support

3.3.2. Marital Experiences

3.3.3. Concerns Related to the Future of Family Members with ID

3.3.4. Coping with A Child with ID

3.4. Theme II: Prevalence of Neurodevelopmental and Behavioural Conditions in Children and Yound People with ID

3.5. Theme III: Sexual Experiences of People with ID

3.6. Theme IV: Language Comprehension, Social and Entrepreneurship Skills and People with ID

4. Discussion

- the experiences of caregivers supporting a family member with ID;

- the presence of additional neurodevelopmental and behavioural difficulties dis-played by children and young participants with ID;

- the sexual activities of participants with ID;

- English language comprehension, social skills and the need for entrepreneurial skills of young people with ID in Nigeria.

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maulik, P.K.; Mascarenhas, M.N.; Mathers, C.D.; Dua, T.; Saxena, S. Prevalence of intellectual disability: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njenga, F. Perspectives of intellectual disability in Africa: Epidemiology and policy services for children and adults. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2009, 22, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckenzie, J.A.; McConkey, R.; Adnams, C. Intellectual disability in Africa: Implications for research and service development. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1750–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sango, P.N. Country profile: Intellectual and developmental disability in Nigeria. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2017, 22, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capri, C.; Abrahams, L.; McKenzie, J.; Mkabile, S.; Saptouw, M.; Hooper, A.; Smith, P.; Adnams, C.; Swartz, L.; Ockert Coetzee, O.C. Intellectual disability rights and inclusive citizenship in South Africa: What can a scoping review tell us? Afr. J. Disabil. 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasko, A.M.; Morin, K.L.; Bauer, K.; Johnson, K.M.; Enriquez, G.B.; Hunsicker, L.E.; Tasik, E.J.; Renz, T.E., III. A Meta-Synthesis of Disability Research in Western Africa. J. Spec. Educ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization & The World Bank. World Report on Disability. 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44575 (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- The World Bank. Nigeria Releases New Report on Poverty and Inequality in Country. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/lsms/brief/nigeria-releases-new-report-on-poverty-and-inequality-in-country (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- McConkey, R.; Kahonde, C.; McKenzie, J. Tackling Stigma in Developing Countries: The Key Role of Families. In Intellectual Disability and Stigma: Stepping Out from the Margins; Scior, K., Werner, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rohwerder, B. Disability Stigma in Developing Countries; K4D Helpdesk Report; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Fact Book. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/nigeria/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Grace, O.U. The political economy of the proposed Islamic banking and finance in Nigeria: Prospects and challenges. Kuwait Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 1, 16–37. [Google Scholar]

- Groce, N.; Kett, M.; Lang, R.; Trani, J.F. Disability and poverty: The need for a more nuanced understanding of implications for development policy and practice. Third World Q. 2011, 32, 1493–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Posarac, A.; Vick, B. Disability and poverty in developing countries: A multidimensional study. World Dev. 2013, 41, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, L.M.; Polack, S. The Economic Costs of Exclusion and Gains of Inclusion of People with Disabilities; International Centre for Evidence in Disability: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arimoro, A.E. Are they not Nigerians? The obligation of the state to end discriminatory practices against persons with disabilities. Int. J. Discrim. Law 2019, 19, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018, Nigeria. 2019. Available online: https://nigeriahealthwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/bsk-pdf-manager/2019/02/1244-Discrimination-Against-Persons-with-Disabilities-Prohibition-ACT-2018.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Abang, T.B. Disablement, disability and the Nigerian society. Disabil. Handicap Soc. 1988, 3, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.; Upah, L. Scoping Study: Disability Issues in Nigeria; DFID: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scior, K.; Hamid, A.; Hastings, R.; Werner, S.; Belton, C.; Laniyan, A.; Patel, M.; Kett, M. Intellectual Disabilities: Raising Awareness and Combating Stigma—A Global Review; University College London: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/intellectual-developmental-disabilities-research/sites/intellectual-developmental-disabilities-research/files/ExecSummary.pdf.https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ciddr/documents/Global_ID_Stigma_Report_Final_July_15.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Rugoho, T.; Maphosa, F. Challenges faced by women with disabilities in accessing sexual and reproductive health in Zimbabwe: The case of Chitungwiza town. Afr. J. Disabil. 2017, 6, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sango, P.N.; Bello, M.; Deveau, R.; Gager, K.; Boateng, B.; Ahmed, H.K.; Azam, M.N. Exploring the role and lived experiences of people with disabilities working in the agricultural sector in northern Nigeria. Afr. J. Disabil. 2022, 11, a897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. The Washington Group Extended Set on Functioning (WG-ES) Questionnaire. 2010. Available online: https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/question-sets/wg-extended-set-on-functioning-wg-es/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Ijezie, O.A.; Okagbue, H.I.; Oloyede, O.A.; Heaslip, V.; Davies, P.; Healy, J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Nigeria. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajuwon, P.M. A Study of Nigerian Families Who Have a Family Member with Down Syndrome. J. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 18, 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. Thematic content analysis (TCA). Thematic Content Analysis (TCA): Descriptive Presentation of Qualitative Data. 2007. Available online: http://rosemarieanderson.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/ThematicContentAnalysis.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Onyedibe, M.C.C.; Ugwu, L.I.; Mefoh, P.C.; Onuiri, C. Parents of children with Down Syndrome: Do resilience and social support matter to their experience of carer stress? J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajuwon, P.M.; Brown, I. Family quality of life in Nigeria. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eni-Olorunda, T.; Ariyo, M.; Lasode, A. Influence of the presence of a child with intellectual disability on marital stability in south-west Nigeria. Afr. J. Psychol. Stud. Soc. Issues 2015, 18, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu, N.E.; Okoye, U.O.; Onyeneho, N.G.; Okeibunor, J.C. Coping strategies of families of persons with learning disability in Imo state of Nigeria. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2019, 38, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aderemi, T.J.; Pillay, B.J. ‘Sexual or not?’: HIV & AIDS knowledge, attitudes and sexual practices among intellectually impaired and mainstream learners in Oyo State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Rhetor. 2011, 3, 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Aderemi, T.J.; Pillay, B.J. Sexual abstinence and HIV knowledge in school-going adolescents with intellectual disabilities and non-disabled adolescents in Nigeria. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2013, 25, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aderemi, T.J.; Pillay, B.J.; Esterhuizen, T.M. Differences in HIV knowledge and sexual practices of learners with intellectual disabilities and non-disabled learners in Nigeria. J. Int. Aids Soc. 2013, 16, 17331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, M.O.; Ebigbo, P.O.; Ubochi, V.N. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among Nigerian children with intellectual disability: A stopgap assessment. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2012, 23, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, M.O.; Ubochi, V.N.; Ebigbo, P.O.; Orovwigho, A.O. Problem and pro-social behavior among Nigerian children with intellectual disability: The implication for developing policy for school based mental health programs. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2010, 36, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atilola, O.; Omigbodun, O.; Bella-Awusah, T.; Lagunju, I.; Igbeneghu, P. Neurological and intellectual disabilities among adolescents within a custodial institution in South-West Nigeria. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eni-Olorunda, T.; Adediran, O.A. Socio-economic status difference in English language comprehension achievement of pupils with intellectual disability. IFE Psychol. Int. J. 2013, 21, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Adeniyi, Y.C.; Omigbodun, O.O. Effect of a classroom-based intervention on the social skills of pupils with intellectual disability in Southwest Nigeria. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2016, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isawumi, O.D.; Oyundoyin, J.O. Home and School Environments as Determinant of Social Skills Deficit among Learners with Intellectual Disability in Lagos State. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Olufemi, A.M.; Favour, J.T.; Olaosebikan, O.A. Efficacy of Vocational Training as an Integral Part of Entrepreneurship Education as a Transition Programme for Persons with Intellectual Disability in Oyo State. Adv. Econ. Bus. 2008, 5, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, Y.C.; Adeniyi, A.F. Development of a community-based, one-stop service centre for children with developmental disorders: Changing the narrative of developmental disorders in sub-Saharan Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostert, M.P. Stigma as a barrier to the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Africa. Afr. Disabil. Rights Yearb. 2016, 4, 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K.R.; Purcal, C. Policies to change attitudes to people with disabilities. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2017, 19, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeo, R.; Moore, K. Including disabled people in poverty reduction work: “Nothing about us, without us”. World Dev. 2003, 31, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasha, T.N.; Myaka, L.D. Sexuality and sexual abuse involving teenagers with intellectual disability: Community conceptions in a rural village of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sex. Disabil. 2014, 32, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürol, A.; Polat, S.; Oran, T. Views of mothers having children with intellectual disability regarding sexual education: A qualitative study. Sex. Disabil. 2014, 32, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aley, R. An Assessment of the Social, Cultural and Institutional Factors that Contribute to the Sexual Abuse of Persons with Disabilities in East Africa. Advantage. 2016. Available online: https://www.advantageafrica.org/file/advantage-africa-full-research-report-sexual-abuse-of-persons-with-disabilities-pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

| Intellectual Disability | Nigeria |

|---|---|

| Disab *, autism *, mental retard * developmental disorder * and special educational need. * The last three keywords incorporated the following terms: Down’s Syndrome, fragile X, learning disability, intellectual disability, learning difficulty and foetal alcohol syndrome | Nigeria |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sango, P.N.; Deveau, R. A Scoping Review of Empirical Literature on People with Intellectual Disability in Nigeria. Disabilities 2022, 2, 474-487. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030034

Sango PN, Deveau R. A Scoping Review of Empirical Literature on People with Intellectual Disability in Nigeria. Disabilities. 2022; 2(3):474-487. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleSango, Precious Nonye, and Roy Deveau. 2022. "A Scoping Review of Empirical Literature on People with Intellectual Disability in Nigeria" Disabilities 2, no. 3: 474-487. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030034

APA StyleSango, P. N., & Deveau, R. (2022). A Scoping Review of Empirical Literature on People with Intellectual Disability in Nigeria. Disabilities, 2(3), 474-487. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities2030034