1. Introduction

The sustainable management of textile waste, including recollection logistics, material classification, and maximizing recycling opportunities, constitutes a critical challenge within the framework of the circular economy [

1].

The textile and clothing sector is widely recognized as one of the most resource-intensive industries, generating a substantial environmental footprint from raw material extraction through to end-of-life disposal [

2,

3]. In response, the European Union’s Circular Economy Action Plan [

4] has instituted rigorous measures to advance sustainable consumption, such as the mandatory separate collection of textile waste by January 2025 [

5], the prohibition of destroying unsold or returned textile goods [

6], and restrictions on the non-EU export of textile waste [

7].

Despite these regulatory efforts, a significant volume of post-consumer textile waste is improperly discarded into the general mixed waste stream and it ends up landfilled or incinerated [

8]. In the specific case of Spain and Catalonia, although national legislation (BOE-A-2022-5809) [

9] has established the separate municipal collection as stated by the EU, public awareness related to this separate recollection remains low. The prevalent perception among consumers is that the municipal system is a voluntary, charitable mechanism for textile reuse, primarily because the service is often managed by the same social organizations that handled pre-directive collection [

10]. Consequently, an estimated 89% of discarded textile material is either incorrectly placed in the rejection fraction or acts as a contaminant in other selective streams [

11].

Nevertheless, the disparity between collected and lost material is significant. Specifically, separately collected textile waste in Catalonia represented a mere 0.6% of the total municipal waste in 2024. However, given that the residual fraction accounts for approximately 53% of all collected waste, and an estimated 4 % of this residual stream is textile, the scale of material loss is alarming: the textile volume in the residual fraction was approximately 81,802 tones, relative to only 23,195 tones collected through the appropriate recollection system [

12]. This demonstrates that the unrecovered waste stream exceeds the volume of properly managed textiles by more than three-fold. Critically, even when the residual waste undergoes mechanical separation processes aimed at recovering other materials, the embedded textile waste is typically not recycled and is ultimately relegated to landfilling or energy valorization.

Beyond the documented volumetric loss, existing literature on textile waste management emphasizes other critical challenges. Allwood et al. (2006) exposed the increasing material complexity of post-consumer textiles, marked by a proliferation of blended fibers that severely hinder the chemical and mechanical recycling processes [

13]. Furthermore, the high prevalence of non-textile components (e.g., zippers and buttons) in discarded items acts as a significant impediment, functioning as contaminants and processing disruptors [

14]. While the overall composition of municipal solid waste is extensively documented, a detailed, systematic characterization of the textile fraction specifically embedded within the residual waste bin is conspicuously absent in the literature. On the other hand, different studies have largely concentrated on characterizing the composition of separately collected textile waste (e.g., from specialized containers) [

15,

16,

17]. Crucially, a significant research deficit exists regarding the material properties of textiles entering the general waste stream, which represents a major, unexploited resource. Understanding the characteristics of this lost fraction—including fiber composition, degree of soiling, moisture content, and the nature and volume of recycling contaminants—is indispensable for formulating effective diversion strategies and evaluating its feasibility for high-value resource recovery.

This study addresses a critical knowledge gap by providing a detailed compositional analysis of the textile waste found in the residual fraction (rest) of general waste containers across Catalonia, Spain. While few studies have analyzed this specific waste stream, they typically lack a deep analysis of the intrinsic properties of the textiles involved [

18,

19]. By focusing on the intrinsic properties of this currently unmanaged waste flow, this analysis aims to determine its practical recycling potential. The specific objectives of this research were: (1) to quantify and categorize the textile material within the residual fraction; (2) to characterize its fiber composition and material condition (e.g., cleanliness, humidity) and; (3) to evaluate the quantity and nature of processing disruptors (e.g., zippers, metallic components).

The experimental findings of this study will provide a vital contribution by establishing a clearer understanding of the barriers and opportunities for resource recovery from the general waste stream. These findings may inform policy formulation and drive the development of more efficient textile recycling technologies. A better understanding of this lost textile flow can support both the development of targeted recycling technologies and the design of evidence-based policies, such as the forthcoming Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) scheme for textiles.

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis was conducted on 24 waste batches of approximately 20 kg each, generated in November and December 2024 in Catalonia, Spain, and sorted from 4800 kg of domestic waste generated by an area with around 500,000 population.

Figure 1 schematically illustrates the pathway of the analyzed waste, from the general discard stage to the separation conducted at the university facilities.

The study was carried out in three phases: identification, qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis. The waste batches included non-textile items such as shoes, belts, and bags. These items are typically classified as clothing, hence included in the batch due to the nature of the collection and classification process in the waste management facilities. However, these are mainly non-textile products and/or with a low recycling potential, falling out of the scope of the study, thus were discarded in an initial stage, at the arrival. The weight of this non-textile fraction was recorded and included in the overall results.

2.1. Identification and Characteristics of the Waste

During this first phase, individual textile items were analyzed, and a series of data points were recorded using a custom-built mobile application specifically developed using the Microsoft Power Apps environment (collecting the inputs shown in

Figure 2: identifier number, data, batch, type of item, weight, origin, application and specific subcategories, degree of dirtiness and humidity and presence of recycling disruptors). For efficient data logging and tracking, each textile item was fitted with a polyester fabric label incorporating a Quick Response (QR) code. This code served as the unique digital identifier for the item, thereby linking the physical waste unit to its digital record throughout the entire process chain. Furthermore, a photograph of the textile item, including a visible scale bar for dimensional reference, was captured and logged with its corresponding digital record. From the different data collected, the degree of dirtiness and humidity was subjectively assessed (visual inspection and by touch, respectively) as quantitative criteria could not be established due to the logistical challenges of performing accurate measurements. The classification relied on qualitative criteria consistently applied by the same team of trained authors throughout the sampling period.

Degree of dirtiness was classified into four categories, defined as follows: “very dirty” items exhibited an extensive coverage with visible stains, encrusted dirt and residual materials, with the original color significantly obscured; “dirty items” showed a high coverage of noticeable stains and residual material, with contamination that was widespread and prominent; “slightly dirty” items showed localized presence of minor stains, residual traces or surface soiling; “clean” items were free of discernible stains or residual materials on the surface upon inspection.

Humidity was classified into four categories, defined as follows: “wet items” were visibly dripping water; “very humid” items did not drip water but felt saturated and distinctly moist to the touch; “humid” items did not feel saturated, but a light sensation of coolness was registered through the sampling glove upon contact; “dry” items showed no moisture.

This qualitative approach allowed for consistent classification under varying field conditions, although it introduces a degree of subjective interpretation by the analyst. It is important to remark that, under high volume waste management conditions, quantitative gravimetric analysis of every item is totally unfeasible.

After that initial inspection and classification, samples of approximately 400 cm2 were cut from each item, weighed, and then washed and dried using a domestic cotton program in a household washing machine (AEG 7000 Series), with commercial textile detergent and disinfectant. The conditions for the washing cycles were 2 h at 40 °C with a maximum capacity of 9 kg and for the drying process 2.33 h at 95 °C with a maximum capacity of 5 kg. Before and after washing and drying, the samples with an area of 400 cm2 where weighted to determine quantitatively the humidity and the dirtiness and compare with the results obtained on the qualitative assessment. Moreover, photographs of the samples before and after washing were also recorded on the application.

2.2. Qualitative Analysis of the Composition and Other Textile Characteristics

After washing and drying, samples were weighed again to estimate the moisture content of the collected items. Specimens measuring 9 × 5 cm were cut for further analysis. Areal weight (g/m2) and thickness were determined under standard conditions (23 °C and 50% relative humidity).

Textiles were then classified as monolayer or multilayer. The textile structure (e.g., woven, knitted, non-woven) and color were recorded. Structural identification was determined by textile specialists and using magnifying glasses or stereoscopic microscope. Fiber composition was determined using a trinamiX Mobile NIR Spectroscopy device (Trinamix Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and the associated database provided by the manufacturer. For each sample, three measurements were taken. In the case of cotton/polyester blends, quantitative composition was also recorded when available.

Multilayer textile samples—which represented a small percentage of the analyzed waste—were separated into individual layers, and each layer was analyzed independently.

2.3. Chemical Quantitative Analysis of the Composition

Representative binary blended-fiber samples were selected from each batch for qualitative and quantitative analysis using optical microscopy and dissolution tests in order to validate the results obtained with the NIR equipment. Quantitative determination for binary blends followed the ISO 1833 standard.

3. Results

In the Catalan and Spanish waste management systems, general municipal waste is selectively collected subsequently transferred to a classification facility to improve recycling rates. Although separate collection systems are in place for textiles, glass, and plastic at the national level, individual sorting remains limited, requiring further classification at management facilities. In the case of textiles, this process has led to a loss of raw material flow, and continues to do so, as previously mentioned, due to a lack of detailed information. Thus, the interest of assessing the potential for high-value recycling of the textiles found out of the expected flow.

A total mass of 4800 kg of general municipal waste collected during the analysis period. From this total, a targeted sample of 551.7 kg, initially classified as “textile” at the waste management plant, was extracted and analyzed across 24 batches collected over four distinct weeks. As previously mentioned, the initial characterization process at the university facilities for this study began by addressing the common issue of misclassification observed at management facilities, where workers tend to group textiles with associated items such as shoes and belts. Since these items cannot be processed using textile-specific technologies, they were separated immediately. Therefore, upon detailed post-collection sorting, the 551.7 kg samples of textile separated at the residues management facilities was resolved into 382.7 kg (69.4%) of textile purity fraction and 169.0 kg of non-textile contaminants. Across the 24 batches, this purity fraction averaged 66.9%, with pronounced batch-to-batch variation observed. The total number of individual textile items was 1682, corresponding 4.4 pieces per kilogram on average, consistent with common findings in recycling facilities.

Crucially, based on the total collected waste mass (4800 kg), the actual textile fraction represented approximately 8.0%. This calculated fraction is twice the average value estimated in regional waste characterization studies reported by the Catalan Government [

12]. This finding highlights the significant and currently underestimated volume of recoverable textile resources being directed to landfill or incineration. However, this experimentally determined value may be subject to methodological biases related to the limited sampling period, and thus could be influenced by seasonal or specific weather variations. Once an item was classified as textile, further analysis was conducted to assess its textile-specific characteristics.

3.1. Type of Textile and Origin

The first analysis focused on classifying the 1682 individual items by type and origin to determine the nature of the discarded material. The textiles were grouped according to whether they were full pieces or scraps, and by origin. On the one hand, 84% of the identified items were full pieces whereas the other 16% were scrap textiles (corresponding to a 91% and a 9% in weight, respectively). On the other hand, 96.0% of the items were identified as post-consumer textiles, a 3.6% as pre-consumer textiles, and a 0.4% were unidentifiable, this referring to cases where it was not possible to determine whether the textiles had been previously used. In this case, the percentages comparing by weight corresponds to an 97.3%, 2.6% and 0.1%, respectively. The results clearly demonstrated that the overwhelming majority of the waste consisted of full pieces, confirming the stream’s origin as predominantly post-consumer waste. While assessing the exact degree of use or damage was challenging upon arrival due to the presence of dirt and contamination, the classification was based primarily on the fact that these items were finished garments. Conversely, the presence of pre-consumer items was minimal, as expected, since industrial pre-consumer waste is typically managed through specialized channels and should not enter the general waste stream. The small amount of pre-consumer waste identified is therefore likely related to household consumption.

Analyzing both parameters revealed important statements. Although scraps represented a significant proportion by number of items, their reduced mass resulted in a much smaller proportion by weight. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that while the number of pre-consumer items was low, their weight was relatively high, suggesting that the identified pre-consumer material consisted of long or heavy pieces. Overall, these findings confirm that the stream represents textile discards from post-consumer waste end-of-life, solidifying its identity as a substantial resource for the recycling market.

3.2. Degree of Dirtiness and Humidity

The degree of dirtiness and humidity was initially assessed using the qualitative classification system due to the logistical constraints imposed by the volume of samples and the objective to simulating industrial pre-sorting conditions. The inclusion of these parameter was intended to explore if such factors could be reliably measured through visual inspection.

The qualitative assessment of the degree of dirtiness (

Figure 3, left) highlighted a major challenge for the subsequent intended recycling process of the textile waste: most of the textiles exhibited a high degree of dirtiness—over 70% by number and almost 80% by weight. This dirtiness, which mainly consist of soil and dirt residues, was associated with the co-mingling of textiles with general domestic solid waste during the recollection, transport and first classification at the waste management facility. Nonetheless, this contamination was confirmed to be predominantly on the surface-level and not chemically fixed, a finding replicated throughout the analysis. As shown in

Figure 4, following a standard cleaning cycle in a domestic washing machine, the dirtiness was fully removed from the vast majority of items.

Regarding humidity, approximately 50% of the items were found to be wet or highly humid, with around 40% considered moderately humid (

Figure 3, right). Only about 10% of the items were classified as dry. As expected, the percentage by weight was higher due to the additional mass of water absorbed by the textiles, particularly in hygroscopic fibers like cotton.

To obtain an absolute measurement, samples were weighed before and after washing, drying, and conditioning to assess quantitatively the moisture and dirtiness of the samples. The average humidity and dirtiness of the samples was estimated to be around 19%. A significant discrepancy was found between the quantitative measurements and the initial qualitative assessment, which indicated higher perceived humidity and dirtiness than the measured values. This error is influenced by factors such as the nature of the fiber (a 20% humidity in a cotton sample feels markedly different from the same level in a polyester sample), and external factors like the collection season or the complex chain custody prior to the analysis. In the case of the collection seasons and mainly related to the humidity, colder seasons may increase the perception or retention of moisture. On the other hand, the complex and extensive chain of custody undergone by the textiles prior to our analysis makes it difficult to achieve a confirmation of a direct correlation. The initial humidity and dirtiness condition may have been altered during these intermediate steps. Additionally, the type of containers of collection and the temporary storage containers could also have an influence. Given the variety of types, the quantifiable effect of this factor remains an acknowledged area of uncertainty within this research. Nevertheless, the scope of the study is mainly focused to the textile arrival to university facilities, simulating the arrival to a theoretical textile waste management facility after the recovering of these textiles flow from the general waste. Nonetheless, the results showed that assessing both parameters—dirtiness and humidity—based solely on subjective evaluation was a complex task. Therefore, objective physical measurements are required to accurately quantify these parameters for reliable information, even though these methods are typically time-consuming. Furthermore, it was observed that the vast majority of the items did not appear to be discarded due to irreparable damage (e.g., stains, tears), but rather as a result of consumer behavior.

3.3. Application

The collected textile items were categorized according to their end-use application: fashion, home, or technical textiles, to determine the primary source of the discarded volume. Samples that could not be identified were categorized as unidentifiable.

Figure 5 presents the results by number of items and by weight.

When evaluated by number, the vast majority of items were intended for fashion applications (65%), followed by home textiles (approximately 26%). Technical textiles represented the smallest fraction, accounting for only 7%. This distribution shifts significantly when analyzed by weight, a measure more relevant for industrial recycling processes. The proportion of fashion textiles (54.9%) decreased in favor of home textiles (37.5%), as the latter tend to be larger and heavier. This contrast highlights the key role of item mass in characterizing this waste stream.

Among the fashion textile items (

Figure 6), the most frequent were lightweight garments such as T-shirts (18.4%), followed by socks (17.9%), trousers (17.4%), underwear (10%), and jumpers (9.2%). However, when assessed by weight, heavier garments accounted for the largest share of the material. Trousers constituted the largest fraction (31.7%), followed by jumpers (17.0%), T-shirts (14.9%), and coats/jackets (11.4%). This shift was expected, since these garments are heavier—particularly coats and jackets, which are often multilayered and may include padding. Nevertheless, such garments were less prevalent in the analyzed stream, likely because they are retained longer due to their higher emotional value or are more often directed to appropriate recycling routes recycling (as is commonly the case of the coats and jackets.)

Consistent with the fashion category, the home textile category (

Figure 7) shifted toward heavier items when analyzed by weight. By number, small items dominated, including baizes (24.1%), sheets (12.5%) and towels (10.5%). By weight, however, bed covers accounted for the largest share (18.0%) followed by towels (15.5%) and sheets (13.7%). Overall, these findings confirm that although the stream contains many lightweight pieces, the material-recovery value is concentrated in heavier goods that are replaced less frequently.

Technical textiles (

Figure 8) were diverse, comprising items such as wrappers, samples, covers, bandages, tarpaulins, and technical garment (including textile belts, vests, sports jerseys, mountain jackets, and protective wear). Additionally, some unidentifiable products were classified as technical textiles based on the materials and textile structures observed during the initial classification process.

Finally, a small portion of the textiles consisted of f scraps for which the end-use application could not be determined. This category was almost negligible by weight (0.4%), primarily because scraps have the low mass.

3.4. Presence of Recycling Disruptors

Recycling disruptors refer to any non-textile components present in the items, regardless of their functionality. These materials pose an additional challenge for recycling because they typically require manual removal, increasing cost and processing complexity and, in some cases, leading to losses a of textile material. The analysis of this parameter revealed that, although the majority of individual textile pieces (63% by number) did not contain any recycling disruptors, the percentage of textiles without disruptors was lower when analyzed by weight (52%). This discrepancy was expected, as heavier textile items—such as trousers or jackets in the case of fashion textiles, or upholstery in home textiles—are more likely to include elements like zippers, buttons, elastics, or other non-textile components. Nonetheless, this finding underscores a fundamental trade-off: although most items are clean, the majority of the recovered mass requires a costly pre-processing step.

The types of recycling disruptors identified and their relative contribution to the total analyzed samples, are shown in

Figure 9. The most common components were rubber bands, buttons, and zippers, as well as combinations of the latter two. This distribution was expected, since zippers, buttons, and rubber bands are widely used as closures or fastening elements in fashion and technical textiles. Their prevalence highlights the need for efficient, preferably automated, identification and removal technologies to maximize recycling yields.

3.5. Type of Textile According to the Number of Layers

The majority of the textiles found were single-layered (monolayer) fabrics, which constituted over the 90% of the waste (94% by number and 91% by weight, respectively). Multilayer items accounted for less than 10% in both cases (by number and by weight), a proportion consistent with these items being typically large and heavy garments, such as jackets which were less quantified by number but contributed significantly to the weight fraction. As mentioned in the methodology, multilayer textiles were analyzed separately from single-layer textiles during the second phase of the study.

3.5.1. Single Layer Textiles

Focusing on the majority single-layer textiles, the physical properties analyzed suggested a high degree of suitability for mechanical recycling. The vast majority had areal weights between 100 and 300 g/m

2 (approximately 60%) as shown in

Figure 10 left. The most representative group consisted of textiles with weights ranging from 150 to 200 g/m

2. Moreover, the thickness of the single-layer (monolayer) textiles was generally less than 1.5 mm, with the highest percentage of samples falling within the range of 0.5 to 1.0 mm (

Figure 10, right). These results are consistent with the overall composition of the waste, which was predominantly made up of fashion textiles. Heavier textiles with areal weights above 300 g/m

2 were also present, corresponding to items typically found in home or technical textile categories.

Regarding the textile (fabric) structure (

Figure 11), the waste items were split between knitted fabrics (~63%), followed by woven fabrics (~31%), with only 6% classified as nonwoven fabrics. However, when comparing the percentages by weight, woven fabrics accounted for nearly the same proportion as knitted ones (~50% vs. 47%, respectively), as knitted textiles are often lightweight items such as socks and underwear. The presence of nonwovens was further reduced (to a ~3%) when analyzed by weight due to the low mass of these pieces.

The structural analysis of the items revealed that woven fabrics were predominantly plain, twill, or terry cloths, while other structures such as jacquard or satin were present only in minor proportions (

Figure 11, data in blue). The relative distribution of these structures remained similar when analyzed by weight. These results were also expected as almost all the items analyzed were mainly fashion and home textiles.

As for the knitted textiles, the extensive majority were weft knitted (~89% by number percentage and ~83% in weight percentage, respectively), as can be seen in

Figure 11 (data in green). The result was expected because weft-knitted fabrics are generally more common in apparel production whereas warp-knitted fabrics are more prevalent in technical end-uses [

20].

In terms of nonwoven fabric structure, the vast majority of samples were needle-punched, followed by thermally consolidated fabrics, as shown in

Figure 11 (data in orange). However, the number of nonwoven samples obtained was relatively small. Therefore, the sample size is too limited for the analysis of this type of structure to be considered statistically significant or representative of the broader waste stream.

The complete analysis of the color is included in

Figure 12. Dark tones (black, grey, navy) were the most frequent by number and weight, representing the 40% in both cases. As a significant result for recycling, the evaluation by weight revealed that white textiles emerged as the predominant single color, representing 17.6% of the total mass. This fraction is especially relevant for recycling processes—particularly mechanical and thermomechanical recycling—since white textiles are highly valued due to their ease of recoloring and their potential to produce homogeneous colored yarns.

As observed in

Table 1, he mono-component textiles were dominated by the two most produced textile fibers: Cotton (CO, around 49.8% by number and 51.6% by weight) and polyester (PES, 24.9% by number and 28.4% by weight). This high presence of 100% cotton and polyester aligns with their widespread use in fashion and home textiles and makes the stream exceptionally attractive for both mechanical and chemical recycling. Viscose (CV), a popular fiber in fashion and home goods, was the next most significant component. Notably, polyamide (PA) exhibited a significant discrepancy when comparing its contribution by number and by weight (9.4% vs. 3.7%). This difference suggests that the PA fraction largely consists of small-mass items, probably related to technical textiles. Other fibers, such as polypropylene (PP) and acrylics (PAC), were found in minor quantities, which is consistent with their typical dedication to non-woven applications (PP) or other uses (PAC). Similarly, the identification of a residual fraction of items made of wool and silk was expected, given the higher monetary and emotional value of these goods, which typically reduces their likelihood of being discarded in the general waste stream.

Blended textiles (

Figure 13 yellow) were overwhelmingly composed of cotton mixed with other fibers, representing 66% by number and over 75% of all blends by weight. This predominance remarks the central role of cotton in textile production and emphasizes the viability of targeting the waste stream for cellulosic recovery.

Regarding non-cotton based blended textiles, the remaining blends were primarily polyester-elastane blends, accounting for 50% by number and 41% by weight). Viscose-elastane blends were the next most common, representing 25% by number and 35% by weight. The remaining blends represented a minor fraction of the stream and included polyamide-elastane (PA-EL), acrylic-polyester (PAC/PES), combinations wool with other fibers and a final category of miscellaneous blends. These data highlight the diversity of non-cotton blends and the prominence of elastane as a common component, particularly in products requiring stretch and flexibility—features valued in both fashion and technical textiles. Accordingly, accurate identification and classification of blended materials are essential to optimize recycling strategies and improve the quality of recovered outputs. Elastane is particularly challenging to recycle when blended with other fibers, as it can interfere with both mechanical and chemical recovery processes.

The composition analysis employed near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, a fast and highly scalable technology for industrial sorting, although it exhibited distinct limitations. Approximately 8% of the samples by number and 6% by weight could not be identified by the NIR system, respectively. The inability to identify these samples was primarily due to technical limitations of the NIR system. One major factor was the presence of dark colors, which absorb infrared radiation and reduce the reflected signal, thereby hindering spectral identification. [

21]. Additionally, complex yarn structures, multifilament constructions, non-uniform surfaces, variation in colors and finishing can interfere with the accuracy of detection [

22]. Another restriction is the incomplete reference database used for material identification. The use of NIR technology in the textile sector is still incipient, and the error rate of the equipment remains relatively high. Despite its limitations, the high value of NIR technology in large-scale operations remains critical for the sorting.

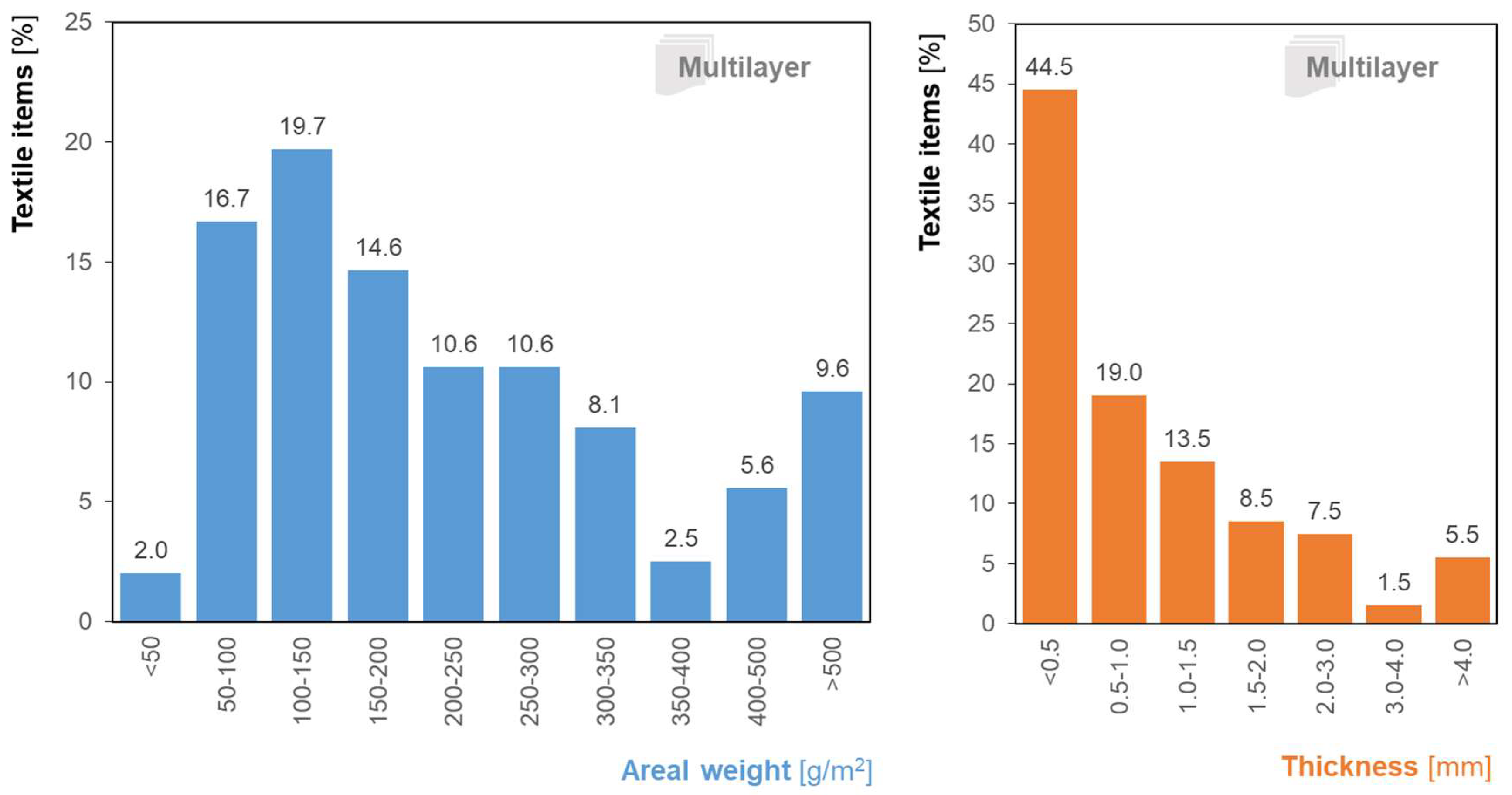

3.5.2. Multilayer Textiles

Regarding the analysis of multilayer textiles (

Figure 14), only 102 items were identified in the waste stream, representing a minority: 6% of the total number of items analyzed and 9% when evaluated by weight. The vast majority of these items (70%) were composed of unbonded layers, which simplifies the potential for separation and recycling. Furthermore, the layer structure was generally simple: 70% were composed of two layers, followed by three layers (28%), with only 2% consisting of four layers. The structure of these items (

Figure 14, right) was primarily knitted (57%) or woven (34%). Nonwoven and mixed layers combining woven and non-woven accounted for a minor share of the stream (5% and 4%, respectively). These structural characteristics, suggest that even this complex fraction may be amenable to mechanical or chemical pre-processing before fiber recovery.

Analysis of the individual layers composing the multilayer textiles revealed that most had areal weights ranging from 50 to 200 g/m

2 (

Figure 15, left) and thicknesses below 1.5 mm (

Figure 15, right). These values are similar to those observed in single-layer textiles, as the analysis considers each layer of the multilayer fabrics separately.

Regarding the color of these fabrics (

Figure 16), approximately 50% were either white or black, followed by other colors such as red and multicolor. A noticeable increase in the presence of white fabrics was observed, which may be attributed to the frequent use of white materials in the inner layers of multilayer assemblies The fiber composition largely maintained the predominance of polyester, cotton-polyester blends, and polyester-elastane (

Table 2), consistent with the overall stream composition. The low sample size for nonwoven structures in both single and multilayer analysis limits the statistical significance of their specific structural breakdown.

3.6. Quantitative Analysis According to ISO 1833 and Comparison with NIR

To assess the precision of the rapid Near-Infrared (NIR) technique for industrial application, a selection of 46 representative textile blend samples was subjected to a quantitative analysis using the definitive ISO 1833 standard. The results highlighted a significant trade-off between the speed of the NIR system and the required analytical precision. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that the high degradation state of the studied textiles challenged both measurements.

Regarding the qualitative composition, the blend items determined by microscopic observation matched the NIR results in 67.4% of the samples. In the remaining discordant cases (32.6%), the NIR correctly identified at least one of the two fibers present. This result underscores the strong utility of NIR for identifying the dominant component in blended textiles, which is relevant for operational sorting decisions, but confirms its current limitation in accurately resolving all fiber components in complex mixtures, especially for automated sorting applications and with the objective of achieving high purity recycling.

The analysis identified several technical limitations of the NIR equipment, including the tendency to underestimate the cotton fraction and overestimate the polyester fraction in CO/PES fabrics (especially in dark or finished samples), the occasional misidentification of polyamide as elastane (due to chemical similarities), and frequent errors with black samples (due to high light absorption). Furthermore, complex yarn structures or surface finishes can interfere with the spectral identification, leading to less accurate readings, especially in finished samples due to the inability to analyze the deeper layers and only detecting the surface layer.

When focusing on quantitative composition—determined only for samples where qualitative results matched—only 37.9% of the samples had matching fiber proportions across both techniques. For the majority (62.1%), the composition determined by NIR showed an error greater than 7%, the error specified by the manufacturer. This significant contrast between quantitative determination by NIR and the ISO 1833 standard illustrates the technological gap: while the ISO method provides an accurate, reproducible reference, it is slow, destructive, and laborious. NIR, in contrast, offers immediacy, portability, and automation potential, but with elevated uncertainty.

Despite these limitations, it must be noted that NIR systems are still under development for textile applications as commented before. However, and although the technology is continuously evolving, the vast diversity of samples, colors, finishes, and fiber combinations makes it difficult to build accurate models. Moreover, NIR models are complex and require ongoing calibration and expansion of the reference database. Therefore, while NIR technology may not yet match the precision of laboratory-based techniques as demonstrated, its speed, portability, and potential for automation make it a key tool for future textile waste management and recycling systems. Even with its limitations, the general coherence of the compositional trends (predominance of cotton, polyester, and their blends) supports the validity of NIR as a composition measurement tool in recycling. The method successfully identifies the dominant flows of textile waste, which is sufficient for operational decision-making in sorting and valorization, although it does not replace laboratory control when regulatory accuracy is required. Furthermore, the practical relevance of the partial match (at least one fiber correctly identified) should be noted. In automated sorting, recognizing the majority fiber could determine, for example, the appropriate subsequent recycling type (mechanical, chemical, or energetic).

4. Considerations for Recycling

The detailed characterization of the textile waste stream recovered from general municipal containers confirms its high potential as a vital source of secondary raw material, provided that the current logistical and technical challenges are addressed. The findings support the strategic importance of diverting this waste flow from landfill.

Analyzing the recycling potential of the waste, several key findings highlight its intrinsic value. The 91% by weight of the waste consisted of single-layer fabrics. Furthermore, approximately 54% of the fabrics weighed less than 250 g/m2, had a thickness below 1 mm, and 57% by weight were knitted fabrics—all characteristics that suggest suitability for mechanical recycling. Crucially, about 54% by weight of the waste was mono-material, with 51.6% composed of 100% cotton. The high purity of these mono-materials facilitates recycling, with cellulosic fibers (cotton and viscose) representing 61.2% by weight, making the stream highly attractive for chemical recycling processes. Additionally, mono-component polyester waste accounts for 28.4% by weight, a significant fraction for potential chemical and/or thermomechanical recycling. Finally, white textiles represent 17.6% by weight, a highly valued color for subsequent recycling operations. Among blended textiles 77% by weight were cotton blends, with cotton-polyester blends representing 51.8%.

However, the initial state of the material presents clear obstacles: the high subjective perception of dirtiness and humidity indicates that mandatory washing and drying steps are necessary, even though the contamination is primarily superficial. Furthermore, the estimated 19% moisture content suggests that the volume of textile waste is significantly overestimated when measured solely by gross collected weight. Another key factor impacting recyclability is the presence of recycling disruptors. Although they are not present in the majority of individual pieces, the fact that nearly half of the total weight (48%) contains these non-textile components means that a costly pre-processing step for removal is mandatory for processing the bulk mass.

Assuming the typology and composition of textile waste found in rejection containers in Catalonia align with to the results of this study, and considering that the Catalan Government estimates that 147,000 tons of textile waste are landfilled annually from these containers, a rough, order-of-magnitude extrapolation suggests that this volume could potentially include approximately: 92,610 tons of textiles without recycling disruptors; 89,964 tons of 100% cellulosic fiber, of which 75,852 tons are 100% cotton; 41,748 tons of 100% polyester fiber; and 25,872 tons of white fibers. These indicative estimations highlight the potential strategic relevance of this alternative waste stream as a source of high-quality raw materials for textile recycling. Its composition—relatively rich in mono-materials, cellulosic fibers, and white fibers- makes it particularly suitable for both mechanical and chemical recycling processes. However, these estimates should be interpreted as exploratory and contingent on the representativeness ofthe sample. Improving the collection, classification, and valorization of textile waste from rejection containers could nonetheless play a key role in advancing circularity within the textile sector in Catalonia and beyond.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a rigorous characterization of the textile fraction within the general municipal waste stream, yielding three major conclusions with implications for the circular economy.

The analysis determined the actual textile fraction within the general waste stream to be approximately 8.0% by mass. This quantification is twice the regional average estimated in waste characterization studies by the Catalan Government. While this experimental value may be influenced by seasonal or specific weather variations, further investigation is required to fully assess and mitigate such methodological variability in future sampling campaigns. Nevertheless, the finding clearly indicates a significant and currently underestimated volume of recoverable textile resources being directed to landfill or incineration.

The study reveals a high potential for recycling, as the waste stream is largely composed of mono-material textiles. Notably, cotton and other cellulosic fibers account for 61.2% by weight, while polyester represents 28.4%. The predominance of single-layer and knitted fabrics, combined with a significant proportion of white textiles (17.6%), suggests strong suitability for all the recycling routes mechanical, thermomechanical and chemical. However, several challenges must be addressed to fully realize this potential. The high levels of dirtiness and humidity—80% and 70% respectively—require an initial washing and disinfection stage, which adds complexity and cost to the recycling workflow. Furthermore, the presence of recycling disruptors, particularly in heavier garments, poses a significant obstacle that must be carefully managed.

In terms of methodological insights, the study underscores the usefulness of NIR spectroscopy for rapid qualitative analysis in textile waste characterization. Even so, it also reveals important limitations, particularly in quantitative accuracy. To improve reliability, it is essential to develop more robust predictive models tailored to the complexity of textile materials. These models must account for the wide variability in fiber types, colors, finishes, and degradation states, and require continuous calibration and expansion of the reference database. Such advancements will make NIR technology achieve the precision necessary for informed decision-making in recycling processes.

The findings of this study provide a valuable characterization of textile waste in the rejection fraction, identifying a significant and recyclable resource. In addition, it emphasizes the strategic importance of this waste stream, which—due to its composition and volume—represents a key opportunity for advancing circularity in the textile sector. Properly harnessing this flow could contribute substantially to reducing landfill dependency and increasing the availability of high-quality secondary raw materials. To achieve this, targeted investments in infrastructure, technology, and policy will be necessary to overcome the current limitations and unlock its full recycling potential.