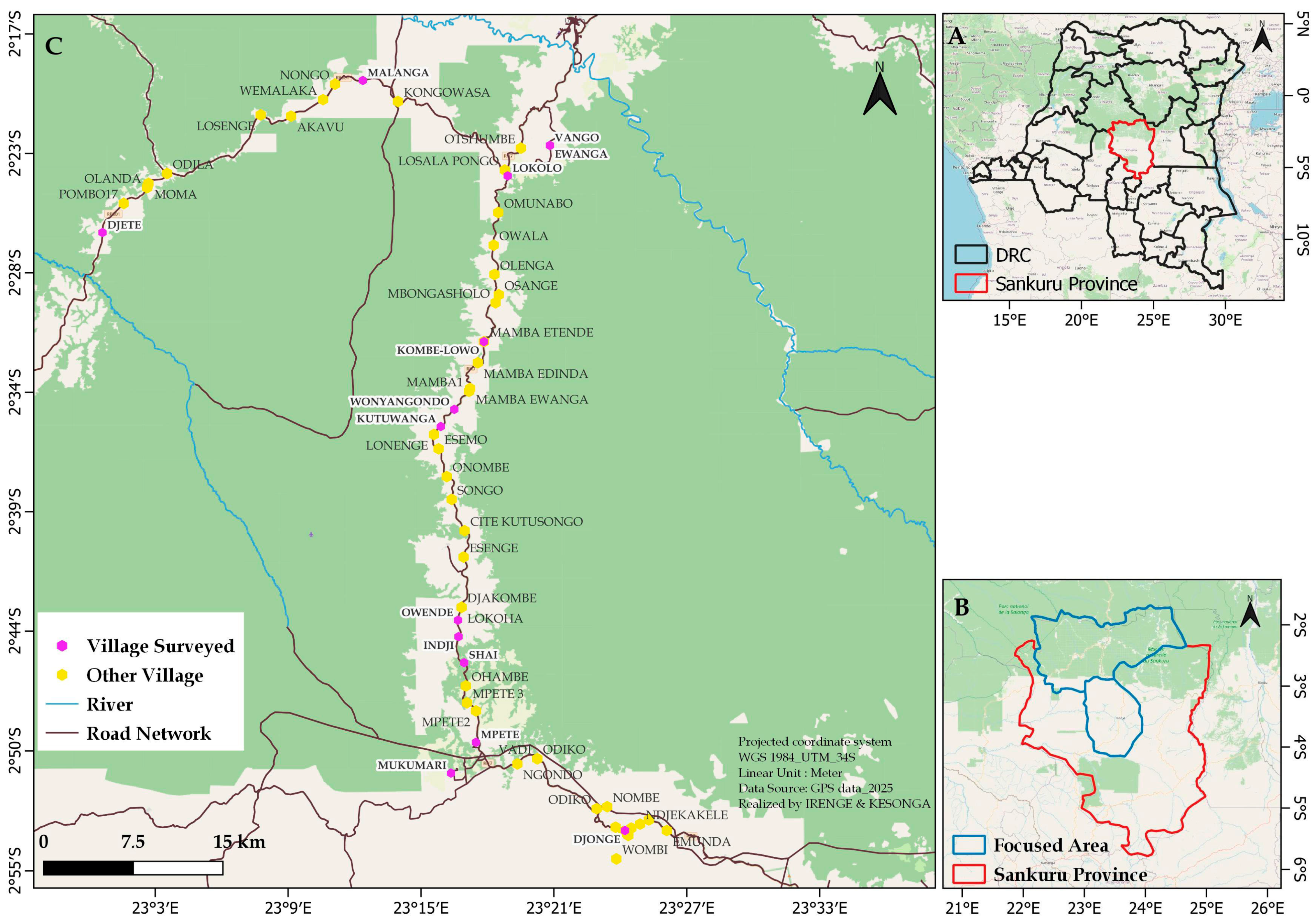

The results below provide an overview of the diversity of the sample and, consequently, of the current situation in the villages of the historical rubber plantations located in the Lomela and Lodja territories.

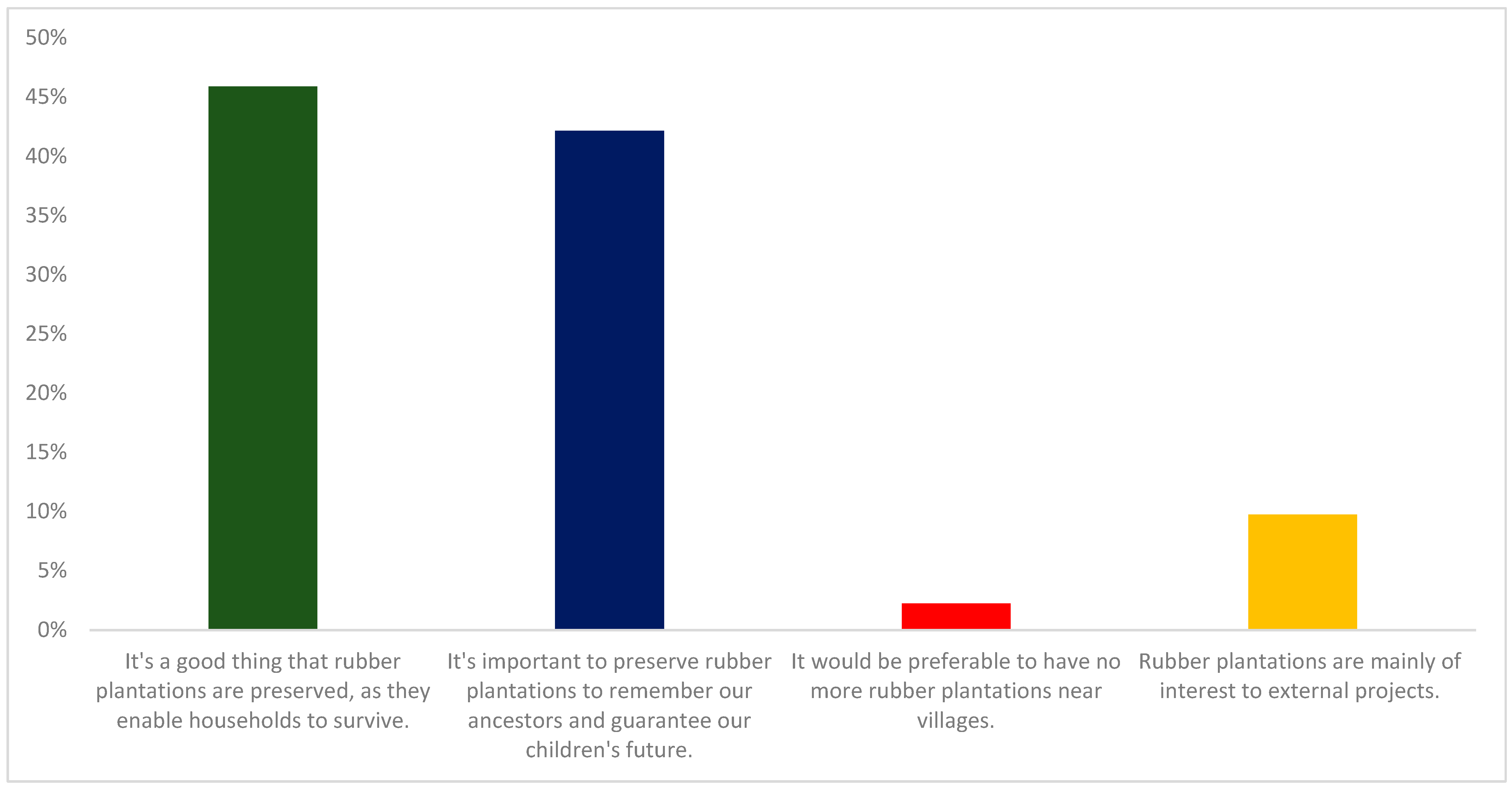

3.2. Respondents’ Perceptions of the Conservation of Historical Rubber Plantations

Figure 3 below shows the distribution of respondents according to their perception of the conservation of historical rubber plantations. The results show that 45.89% of respondents affirmed that it is good that rubber plantations are preserved, as they enable households to benefit from them in the event of a revitalization of its value chain, which would still remain foreseeable, 42.14% of respondents said that it is important to preserve rubber plantations to remember ancestors and guarantee children’s future, 9.73% of respondents said that it would be preferable if there were no more rubber plantations near villages, and 2.24% of respondents said that rubber plantations are mainly of interest to external projects.

This contrast suggests that women may perceive rubber plantation conservation as a means of attracting outside investment, or as being exploited for the benefit of outside stakeholders, rather than as a sustainable local resource. The chi-square test (X

2 = 50.840,

p = 0.000 ***) confirms the statistical robustness of this discrepancy, and indicates a highly significant relationship between gender and perception of rubber plantations (

Table 4). This high significance underlines the existence of a perception inequality between men and women, which can be attributed to socio-cultural and economic factors, such as the division of domestic responsibilities, natural resource management and women’s limited participation in local decision-making processes. During our qualitative interviews, one woman stated that rubber plantations are often subject to projects involving men. Women’s involvement is rarely taken into account. Moreover, rubber plantations occupy land that is close to villages, forcing women to travel long distances in search of arable land, and this is in a cultural context where men rarely accompany women to the fields. The men are content to hunt and fish, sometimes in forbidden areas. This often leads to arrests by the eco-guards and makes household survival more complex. One woman advocates reviving the rubber industry to provide employment for the men, or replacing rubber plantations with the main household survival crops, such as rice and manioc, which are the main food crops in the area.

Furthermore, analysis by age group shows a clear demarcation between young and older people regarding their perception of rubber plantations. Young people (under 45) account for 48.4% of those surveyed with a positive perception of the need to conserve these plantations, while those who are over 45 represent 51.6% of those with the same opinion. This distribution suggests a significant difference in attitude according to age, with a more marked tendency among young people to perceive the conservation of rubber plantations as an asset to be protected for future generations. Young people are indeed more inclined to see the conservation of rubber plantations as essential to securing future generations’ futures, which could reflect a heightened awareness of environmental and sustainability issues. This positive perception could be linked to a greater openness to sustainable development ideas and a desire to bequeath a favorable environment to future generations. On the other hand, although also they share a positive perception of conservation, older people seem to have a more nuanced view of the situation, probably due to their direct experience and adaptation to past changes, notably socio-economic and environmental evolutions linked to rubber plantations.

The chi-square test (X2 = 12.180, p = 0.007 **) supports this hypothesis, revealing a moderate and statistically significant association between age and perception of rubber plantation conservation. These results suggest that age has a substantial influence on how individuals perceive the conservation of these plantations. It would be pertinent to examine in more detail the factors underlying these divergences, exploring how different generations approach natural resource management issues and how their past experiences shape their vision of the future. Such analyses could offer avenues for the development of intergenerational conservation strategies that are better adapted to the specific perceptions and needs of the young and old alike.

With regard to the status of the head of household, the results reveal a marked distinction between individuals who occupy this role and those who do not. Household heads, who accounted for 95.5% of respondents, had a significantly more favorable and pronounced perception of the importance of rubber plantations. This trend could be explained by the fact that heads of household are often responsible for managing domestic and economic resources, and therefore have a vested interest in maintaining plantations to guarantee their family’s long-term food and financial security. Their perception could also be influenced by a heightened sense of intergenerational responsibility, as they are responsible for preserving resources for future generations of their children or relatives. On the other hand, those who do not exercise responsibility tend to adopt a more distant stance with regard to the conservation of rubber plantations. A significant proportion of these individuals (25.6%) feel that plantations are mainly of interest to external projects. This could be due to their less direct involvement in the management of family or community resources, reducing their perception of the importance of these plantations in their daily lives or their future. In addition, non-household heads may perceive plantations as resources linked more to external issues, such as economic projects, than to immediate domestic or community concerns.

The difference observed between these two groups is highly significant, as indicated by the chi-square test value (X2 = 45.198, p = 0.000 ***), suggesting that household head status is a determining factor in the perception of rubber plantation conservation. This result highlights the importance of social position and responsibilities within the family structure, which appears to play a crucial role in how individuals value natural resources and make decisions regarding their conservation. Future studies should explore in greater depth the impact of power dynamics within households and communities on natural resource management, particularly in rural contexts where family structures are often influential in decision-making.

Analysis of the respondents’ social and legal organization reveals an almost absolute prevalence of the patriarchal system, with 98.8% of respondents adhering to this model. This social and legal structure has a significant influence on the perception of rubber plantations, particularly how these plantations are perceived as being primarily associated with development projects. Indeed, a consistent majority of participants who evolve within a patriarchal framework seem to consider rubber plantations not only as an economic resource but also as a lever for development initiatives or external interests, such as research projects and community support programs. The dominance of the patriarchal system in the region may explain this orientation, where power and decision-making structures are concentrated within men, who are generally perceived as the main holders of family and community authority. This dynamic may influence the perception of rubber plantations, which are then interpreted as assets for development or investment projects, rather than as conservation elements linked to environmental or intergenerational issues. It is likely that in such a context, individuals, particularly those who do not exercise significant decision-making power (such as women or young people), may have a more instrumentalized vision of these plantations, linking them more to external projects or immediate profit objectives than to a sustainable conservation perspective.

The statistical significance of this relationship is indicated by the chi-square test, whose value (X2 = 28.696, p = 0.000 ***) shows that belonging to a patriarchal social organization is strongly linked to the perception that rubber plantations are mainly associated with development projects. This statistical association highlights the structural impact that social hierarchy can have on perceptions of natural resources.

In terms of management and conservation policy, it is therefore essential to consider the influence of the patriarchal model in rubber plantation management strategies. An approach that fails to take this reality into account risks failing to respond adequately to the concerns and needs of different categories of the local population, particularly women and young people, who may be under-represented in decision-making processes linked to plantation management. A more in-depth analysis of power relations within communities would therefore be beneficial in developing conservation policies that are more inclusive and better adapted to existing social structures.

Analysis of perceptions of rubber plantations by geographical origin reveals a marked distinction between natives and non-natives. Indeed, most indigenous respondents (89.8%) expressed a positive perception of the conservation of rubber plantations, suggesting a stronger attachment to the sustainable management of this natural resource. Conversely, a significantly lower proportion of non-natives (10.2%) see these plantations as relevant to development projects, rather than as a heritage to be preserved for future generations. This difference in perception between indigenous and non-indigenous groups is statistically significant, as confirmed by the chi-square test (X2 = 7.823, p = 0.000 ***), indicating a direct relationship between respondents’ geographical origin and their view of the conservation of rubber plantations. This result highlights the importance of geographical origin in shaping perceptions, suggesting that natives, who are probably more rooted in the territory and local resource management, develop a more favorable perception of plantation conservation as a common and sustainable good. On the other hand, non-natives, who may be less involved in the day-to-day management of plantations or less familiar with local dynamics, tend to perceive these plantations from a more utilitarian angle, focused on external projects.

This distinction also reveals cultural and socio-economic aspects that influence how different communities perceive rubber plantations. Indigenous people, likely to have a historical and ongoing relationship with these plantations, might perceive their conservation as necessary to maintain their traditional way of life. In contrast, non-indigenous people, often associated with external dynamics, might see them more as resources to be exploited as part of development projects or for economic purposes. The results underline that an approach to the management and conservation of these plantations cannot be practical without a thorough understanding of cultural differences and the varied perceptions that arise from them.

The analysis of respondents’ economic characteristics in relation to their perception of rubber plantation conservation, as presented in

Table 5, reveals several significant trends, both in terms of plantation acquisition, main activities, and the diversification of income sources. These economic variables are strongly associated with how individuals perceive the conservation of rubber plantations, and the statistical results corroborate this association with very marked significances.

The method of plantation acquisition was found to be a determining factor in respondents’ perceptions. Indeed, the chi-square test results (X2 = 98.758, p = 0.000 ***) reveal a highly significant association between this mode of acquisition and perceptions of rubber plantation conservation. Those who acquired their plantations by inheritance feel it is important to conserve them to ensure their daily lives (92.9%) and those of future generations (94.7%), thanks to the ecosystem services these plantations provide. A few respondents consider plantations to only concern external projects (35.7%). On the other hand, plantation buyers seem less likely to think that these plantations should be conserved or protected, and more likely to perceive these plantations as interesting mainly for external projects. This suggests that an acquisition by inheritance is potentially perceived as an ancestral and lasting link with the land. In contrast, a purchase could imply a more utilitarian or commercial vision of the plantation, more focused on immediate profitability. Results relating to respondents’ main activity also significantly affect their perception of rubber plantations. The chi-square test reveals moderate significance (X2 = 35.799, p = 0.007 **), indicating that the main sector of activity influences how individuals perceive the conservation of these plantations. Those whose main occupation is farming have a significantly more positive perception of the need to conserve and protect rubber plantations, particularly with regard to conservation for future generations. In contrast, individuals whose main activity is livestock rearing, hunting or fishing seem to be more distant from the issues of rubber plantation conservation, suggesting that their relationship with the plantations is less direct or less involved in the process of sustainable natural resource management. This trend is particularly marked in the group of herders, who have a weaker perception of the importance of plantations, possibly due to their orientation towards other forms of production or resource exploitation.

Diversification of income sources is another relevant economic factor in the analysis of perceptions. The chi-square test (X2 = 19.913, p = 0.000 ***) shows a highly significant relationship between this variable and perceptions of rubber plantation conservation. However, individuals who have diversified their sources of income (notably through agriculture and other economic activities) have a more marked perception of the importance of plantation conservation. They are also more likely to stress the need to protect these plantations for future generations, suggesting that those with multiple sources of income are more likely to adopt a long-term, sustainable approach to natural resources, as opposed to those whose income is more dependent on a specific economic activity, who may adopt a more short-term outlook. On the other hand, those who do not diversify their sources of income tend to have a less favorable perception of the conservation and protection of rubber plantations, which could be linked to a more immediate focus on short-term economic gains, to the detriment of long-term environmental issues.

The results in

Table 6 are interpreted based on an analysis of respondents’ perceptions of rubber plantations in relation to certain organizational and institutional characteristics. This analysis was structured by examining each independent variable, the results of the chi-square test, and the implications of the results within a rigorous framework.

The chi-square test revealed a significant association between membership in a social organization and the perception of rubber plantations (p = 0.013 *). Indeed, 47.8% of members of a social organization consider it good to conserve rubber plantations, and 51.5% think that it is important to protect them for future generations. On the other hand, among non-members, these perceptions are less pronounced (52.2% and 48.5%, respectively). The non-member group presents a higher proportion of individuals who prefer the cessation of rubber plantations (77.8%). These results suggest that involvement in a social organization could positively influence perceptions linked to plantation conservation, making them more sensitive to issues of sustainability and intergenerational transmission.

Statistical analysis also shows a significant association between access to an informal self-help network and perception of rubber plantations (p = 0.029 *). Among those who benefit from such networks, a higher proportion consider plantations something that should be protected for future generations (19.5% versus 9.8% among those without access to such networks). Conversely, non-beneficiaries of such networks are more likely to think that plantations should be abandoned (77.8% versus 22.2% among those benefiting from such networks). These results show that informal networks can play an important role in the perception of the benefits of rubber plantations, notably by creating bonds of solidarity and support within local communities.

Membership in a planters’ association is strongly associated with the perception of rubber plantations (p = 0.000 ***). Indeed, a majority of members (65.2%) consider conserving plantations to be beneficial to their economic survival, and 76.9% think that it is crucial to protect these plantations for future generations. On the other hand, a majority of non-members believe that it would be preferable to abandon the plantations (88.9% versus 11.1% of members). This result highlights the importance of planters’ associations in the management and sustainability of rubber plantations, suggesting that collective organization around this activity can positively influence the perception of its long-term benefits.

There is a very strong association between contact with extension services and perception of rubber plantations (p = 0.000 ***). Among those who had been in contact with these services, 64.5% felt that plantation conservation was essential, and 83.7% thought that protecting them for future generations was crucial. In contrast, these perceptions are much less pronounced among those who have not had contact (35.5% and 22.2%, respectively). These results imply that access to extension services, which can provide technical information and practical advice on sustainable plantation management, is crucial to improving farmers’ perceptions of the long-term value of rubber plantations.