Rock and Plovers—A Drama in Three Acts Involving a Big Musical Event Planned on a Coastal Beach Hosting Threatened Birds of Conservation Concern

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Act I (The Premises)

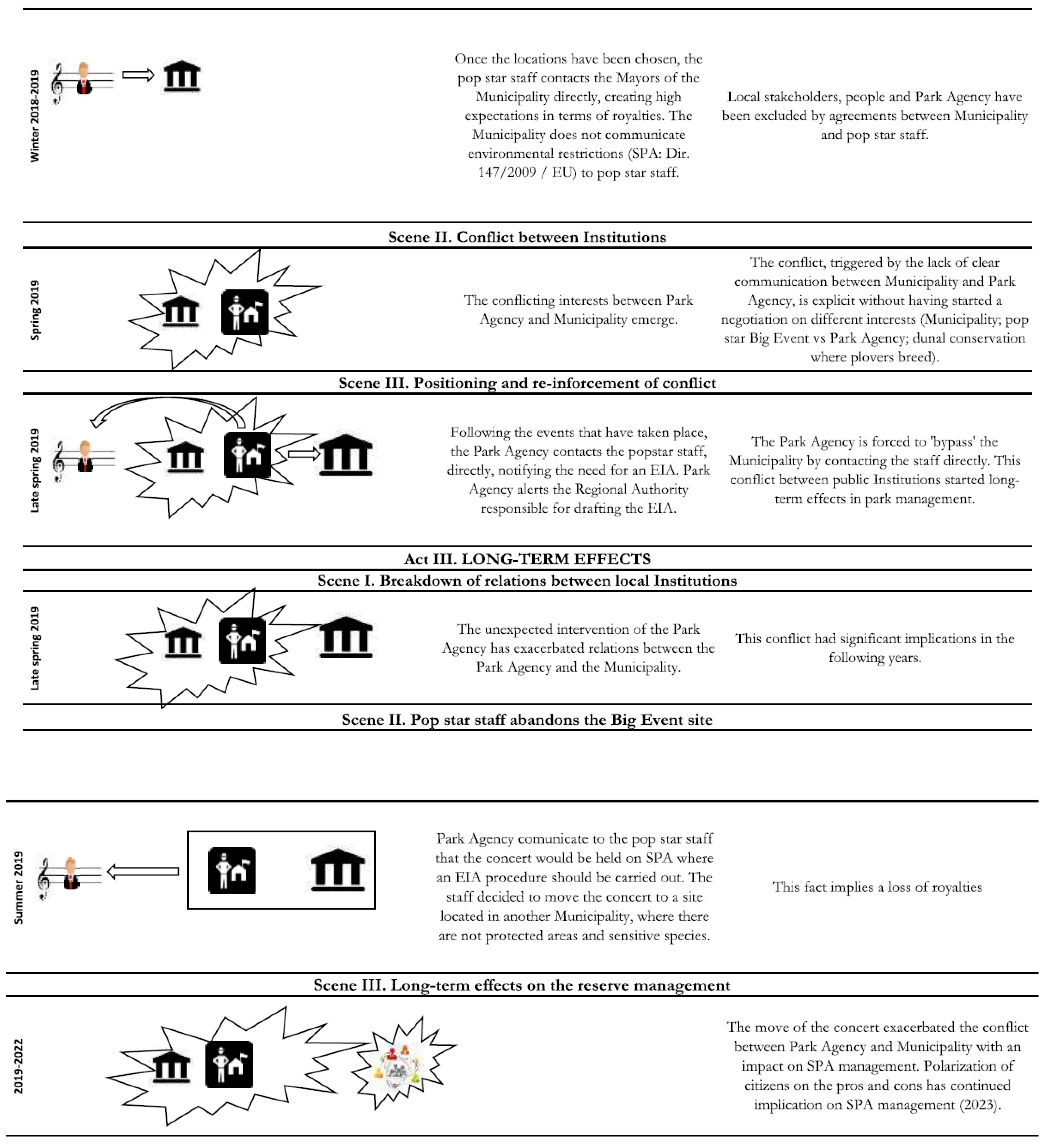

3.2. Act II (On the Field)

3.3. Act III (Long-Term Effects)

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- TripAdvisor. Concerts and Shows in The Alps. 2021. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g2324478-Activities-c58-The_Alps.html (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Wikipedia. T4 on the Beach. 2021. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T4_on_the_Beach (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Jiang, J.J.; Lee, C.L.; Fang, M.D.; Tu, B.W.; Liang, Y.J. Impacts of emerging contaminants on surrounding aquatic environment from a youth festival. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriolo, U.; Gonçalves, G. Impacts of a massive beach music festival on a coastal ecosystem—A showcase in Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 861, 160733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battisti, C.; Marini, F.; Sarrocco, S.; De Santis, E.; Savo, E. Analisi degli impatti di un evento musicale (Jova Beach Party, Campo di Mare, Italia centrale) su comunità ornitiche urbane e di mosaico ambientale: Prime evidenze. Alula 2019, 26, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Normandale, P.; Firth, H. Jova Beach Party Tours Italy with PROLIGHTS: Much more Than a Concert! Music and Light. 2019. Available online: https://www.musiclights.it/news_eventi.html?ID=233andlang=ENandlang=ITandlang=ITandlang=EN (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Salafsky, N.; Salzer, D.; Stattersfield, A.J.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Neugarten, R.; Butchart, S.H.; Collen, B.; Cox, N.; Master, L.L.; O’Connor, S.; et al. A standard lexicon for biodiversity conservation: Unified classifications of threats and actions. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFries, R.; Nagendra, H. Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science 2017, 356, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, P. Much Ado about Jovanotti: The Jova Beach Party. Italics Magazine. 2019. Available online: https://italicsmag.com/2019/08/29/much-ado-about-jovanotti-the-jova-beach-party/ (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Battisti, C.; Cento, M.; Fraticelli, F.; Hueting, S.; Muratore, S. Vertebrates in the “Palude di Torre Flavia” Special Protection Area (Lazio, Central Italy): An updated checklist. Nat. Hist. Sci. 2021, 8, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C.; Perchinelli, M.; Luiselli, L.; Dendi, D.; Vanadia, S. Cages Mitigate Predation on Eggs of Threatened Shorebirds: A Manipulative-Control Study. Conservation 2022, 2, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrelli, L.; Biondi, M. Long term reproduction data of Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus along a Mediterranean coast. Bull.-Wader Study Group 2012, 119, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, C.; Luiselli, L.; Pantano, D.; Teofili, C. On threats analysis approach applied to a Mediterranean remnant wetland: Is the assessment of human-induced threats related to different level of expertise of respondents? Biodiv. Conserv. 2008, 17, 1529–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C.; Luiselli, L.; Teofili, C. Quantifying threats in a Mediterranean wetland: Are there any changes in their evaluation during a training course? Biodiv. Conserv. 2009, 18, 3053–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C.; Gallitelli, L.; Vanadia, S.; Scalici, M. General macro-litter as a proxy for fishing lines, hooks and nets entrapping beach-nesting birds: Implications for clean-ups. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battisti, C.; Perchinelli, M.; Luiselli, L.; Amori, G. A “diary of events” to support the management actions on two beach-nesting birds of conservation concern: Historicization of experiences, learned lessons, and SWOT analysis. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.K.; McDuff, M.D.; Monroe, M.C. Conservation Education and Outreach Techniques; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heras, M.; Tàbara, J.D. Conservation theatre: Mirroring experiences and performing stories in community management of natural resources. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesch, C.; Gnakouri, C.; Marques, L.; Nohan, G.; Herbinger, I.; Lauginie, F.; Boesch, H.; Kouamé, S.; Traoré, M.; Akindes, F. Chimpanzee conservation and theatre: A case study of an awareness project around the Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire. In Conservation in the 21st Century: Gorillas as a Case Study; Stoinski, T.S., Steklis, H.D., Mehlman, P.T., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Pereira, H.M.; McKee, E.; Ceballos, O.; Martín-López, B. Social actors’ perceptions of wildlife: Insights for the conservation of species in Mediterranean protected areas. Ambio 2022, 51, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, D.M.; Tapella, E.; Quétier, F.; Díaz, S. The social value of biodiversity and ecosystem services from the perspectives of different social actors. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, P.; Brost, B. Use of land facets to plan for climate change: Conserving the arenas, not the actors. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandii, M.G.; Prisco, I.; Acosta, A.T.R. Hard times for Italian coastal dunes: Insights from a diachronic analysis based on random plots. Biodiv. Conserv. 2018, 27, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.T. Coastal Dune Vegetation Zonation in Italy: Squeezed Between Environmental Drivers and Threats. In Tools for Landscape-Scale Geobotany and Conservation; Pedrotti, F., Owen Box, E., Eds.; Springer Books: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Drius, M.; Jones, L.; Marzialetti, F.; de Francesco, M.C.; Stanisci, A.; Carranza, M.L. Not just a sandy beach. The multi-service value of Mediterranean coastal dunes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, P.; Spinella, G.; Zafarana, M.A.; Barbera, A.; Cusmano, A.; Cumbo, G.; D’Amico, D.; Grimaldi, D.; Ientile, R.; Laspina, F.; et al. Status, distribution and conservation of Kentish plover Charadrius alexandrinus (Aves, Charadriiformes) in Sicily. Nat. Hist. Sci. 2021, 9, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.H.; Carpenter, S.R.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N.; Cumming, G.S.; Janssen, M.A.; Lebel, L.; Norberg, J.; Peterson, G.D.; Pritchard, L. Resilience management in social–ecological systems: A working hypothesis for a participatory approach. Conserv. Ecol. 2002, 6, 14. Available online: http://www.consecol.org/vol6/iss1/art14/ (accessed on 15 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Cusack, J.J.; Bradfer-Lawrence, T.; Baynham-Herd, Z.; Castello y Tickell, S.; Duporge, I.; Hegre, H.; Moreno Zarate, L.; Naude, V.; Nijhawan, S.; Wilson, J.; et al. Measuring the intensity of conflicts in conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunewald, R. Assessment of damages from recreational activities on coastal dunes of the southern Baltic Sea. J. Coast. Res. 2006, 22, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defeo, O.; McLachlan, A.; Armitage, D.; Elliott, M.; Pittman, J. Sandy beach social–ecological systems at risk: Regime shifts, collapses, and governance challenges. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 19, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hacker, S.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 2011, 81, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanini, L.; Costa, L.L.; Zalmon, I.R.; Riechers, M. Social and ecological elements for a perspective approach to citizen science on the beach. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 694487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.R.; Defeo, O. Sandy shore ecosystem services, ecological infrastructure, and bundles: New insights and perspectives. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 57, 101477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Lucia, M.R.; Comín, F.A.; Escalera-Reyes, J. A framework for the social valuation of ecosystem services. Ambio 2015, 44, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinner, J. How behavioral science can help conservation. Science 2018, 362, 889–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.; Christie, P.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Curran, D.; Durbin, T.J.; Epstein, G.; et al. Conservation social science: Understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 205, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, B.; Sekulova, F.; Hörschelmann, K.; Salk, C.F.; Takahashi, W.; Wamsler, C. Citizen participation in the governance of nature-based solutions. Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, F.L. Dealing with surprises in environmental scenarios. In Environmental Futures: The Practice of Environmental Scenario Analysis; Alcamo, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C.; Warman, R. Disrupting polarized discourses: Can we get out of the ruts of environmental conflicts? Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2018, 36, 987–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibony, O. You’re about to Make a Terrible Mistake!: How Biases Distort Decision-Making and What You Can Do to Fight Them; Swift Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, A.S.; Redford, K.; Margoluis, R.; Knight, A.T. Black swans, cognition, and the power of learning from failure. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redford, K.H.; Groves, C.; Medellin, R.A.; Robinson, J.G. Conservation stories, conservation science, and the role of the intergovernmental platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Conserv. Biol. 2012, 26, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.J.; Grorud-Colvert, K.; Mannix, H. Uniting science and stories: Perspectives on the value of storytelling for communicating science. Facets 2018, 3, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, L.; Hettinger, A.; Moore, J.W.; Neeley, L. Conservation stories from the front lines. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2005226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundin, A.; Andersson, K.; Watt, R. Rethinking communication: Integrating storytelling for increased stakeholder engagement in environmental evidence synthesis. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, A.D.İ.E. Training Children Environmentalists in Africa: The Learning by Drama Method. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. Environ. Model. 2019, 2, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Margoluis, R.; Stem, C.; Salafsky, N.; Brown, M. Using conceptual models as a planning and evaluation tool in conservation. Eval. Program Plan. 2009, 32, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.E.; Teel, T.; Bruyere, B.; Laurence, S. Metrics and outcomes of conservation education: A quarter century of lessons learned. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.P.; Orvos, D.R.; Cairns, J., Jr. Impact assessment using the before-after-control-impact (BACI) model: Concerns and comments. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1993, 50, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C. Unifying the trans-disciplinary arsenal of project management tools in a single logical framework: Further suggestion for IUCN project cycle development. J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 41, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Battisti, C. Rock and Plovers—A Drama in Three Acts Involving a Big Musical Event Planned on a Coastal Beach Hosting Threatened Birds of Conservation Concern. Conservation 2023, 3, 87-95. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation3010008

Battisti C. Rock and Plovers—A Drama in Three Acts Involving a Big Musical Event Planned on a Coastal Beach Hosting Threatened Birds of Conservation Concern. Conservation. 2023; 3(1):87-95. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation3010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleBattisti, Corrado. 2023. "Rock and Plovers—A Drama in Three Acts Involving a Big Musical Event Planned on a Coastal Beach Hosting Threatened Birds of Conservation Concern" Conservation 3, no. 1: 87-95. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation3010008

APA StyleBattisti, C. (2023). Rock and Plovers—A Drama in Three Acts Involving a Big Musical Event Planned on a Coastal Beach Hosting Threatened Birds of Conservation Concern. Conservation, 3(1), 87-95. https://doi.org/10.3390/conservation3010008