2. Study Area

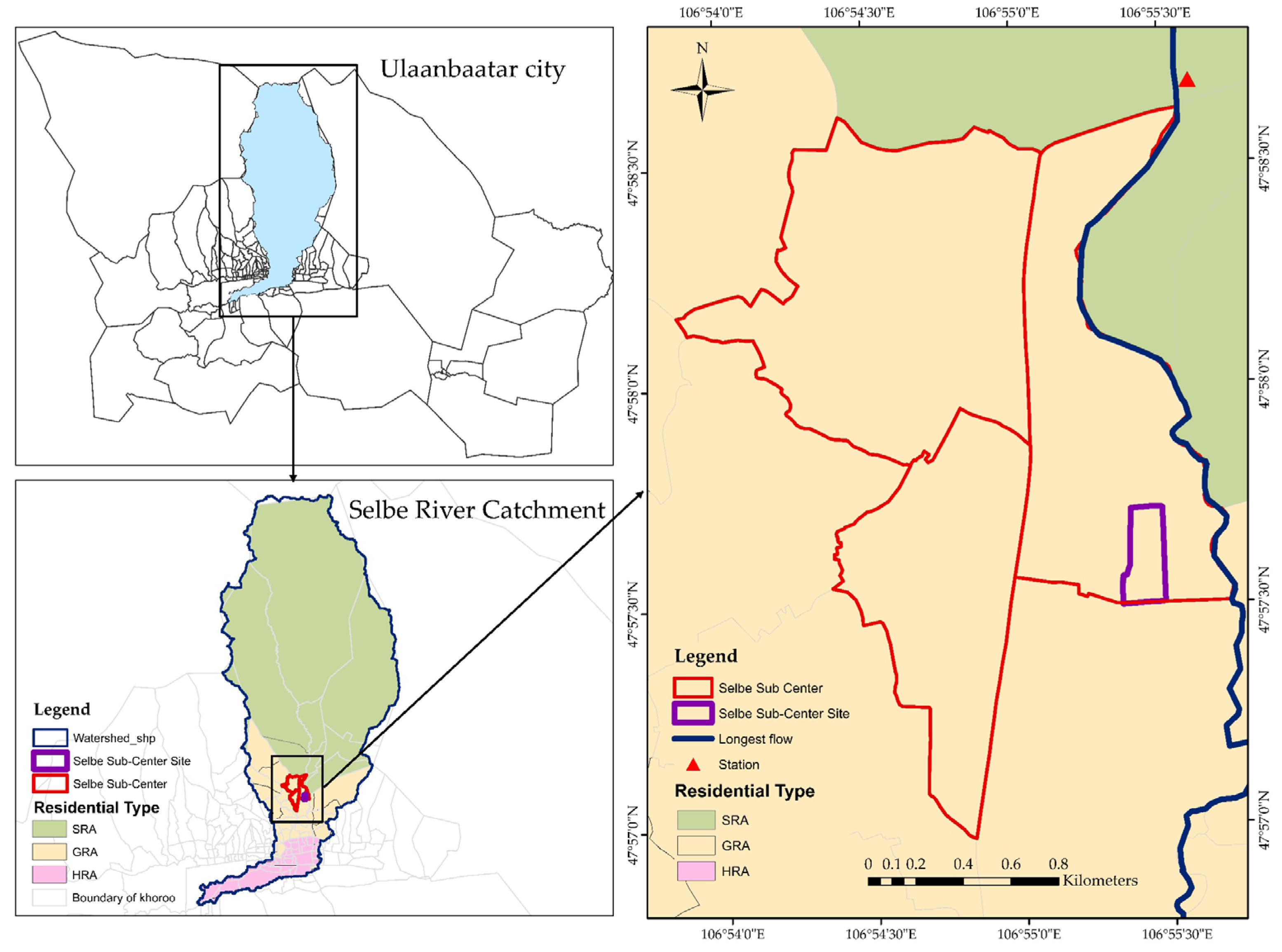

The study site is a 6.08-hectare area located within the Selbe River Catchment in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. The catchment lies in a cold semi-arid climatic zone, characterized by long, cold winters and short summers, with the majority of annual precipitation concentrating in summer months. High potential evapotranspiration further exacerbates seasonal water scarcity. The Selbe River, a tributary of the Tuul River, plays a critical role in the local hydrological system but is increasingly stressed by rapid urban expansion and informal wastewater discharge [

25,

26]. The selected site is located in a ger residential zone characterized by low-density housing, pit latrine sanitation, and limited connection to centralized water infrastructure. Based on Ulaanbaatar’s urban structure, residential areas are classified into three types: Seasonal Residential Areas (SRA), Ger Residential Areas (GRA), and High-Rise Residential Areas (HRA) (

Figure 1). The study site falls entirely within the GRA zone, which is defined by fenced plots, mixed pervious–impervious surfaces, and informal water and sanitation systems. Rapid densification and planned redevelopment make the area representative of broader inner urban transformation processes in Ulaanbaatar. Its proximity to the Selbe–Dambadarjaa gauging station also enables the use of observed hydrological data for model calibration and validation, supporting site-scale water balance assessment [

27].

Several factors guided the selection of the study site. First, the Selbe Sub-Center is part of Ulaanbaatar’s decentralization strategy, as outlined in the 2040 General Plan and the 2050 National Development Concept [

28]. Second, although the total planned redevelopment area covers 158 hectares, this study focused on the initial phase of the housing project to ensure methodological feasibility. According to SUWMBA guidelines, the framework is designed for urban units up to 4 hectares but can be applied to sites as large as 50 hectares when they consist of low-rise buildings and lack specialized rainwater harvesting systems [

29]. Based on these criteria, a 6.08-hectare site represents an appropriate balance between spatial representativeness and model applicability. Finally, the site’s socio-economic characteristics including informal settlement patterns, incomplete infrastructure, and ongoing redevelopment process make it an ideal case for examining how infill densification alters hydrological performance in cold semi-arid urban environments [

21,

26].

4. Results

4.1. Land Cover Change

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial distribution of land cover change, and

Table 2 summarizes the quantitative shifts across categories. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 2, from 2008 to 2023, the study site experienced substantial shifts in land cover. Roof area expanded more than tenfold from 558 m

2 in 2008 to 6681 m

2 in 2023, reflecting the densification of dwellings. On the other hand, the vegetation declined sharply, and barren land fluctuated. These changes increased the effective imperviousness and reduced the evapotranspiration potential, forming the basis for altered site hydrology.

4.2. Performance Evaluation Results for the SUWMBA Framework

Performance evaluation for the SUWMBA framework was conducted by comparing rainfall–runoff calculated using the MUSIC rainfall–runoff tool with observed discharge data from the Selbe–Dambadarjaa gauging station, collected by the Water Supply Authority (WS) and the National Agency for Meteorology and Environmental Monitoring (NAMHEM) during July–August, the main rainy season in Ulaanbaatar [

35]. The Selbe–Dambadarjaa station has continuous multi-year discharge records for 2008–2009, 2010–2011, 2018–2019, and 2023–2024, which were used for model validation. Daily meteorological data for the same periods were obtained from the Terelj meteorological station, located east of Ulaanbaatar in the Terelj–Terelj Gol area. The locations of both the Terelj rain gauge and the Selbe–Dambadarjaa discharge station are shown in

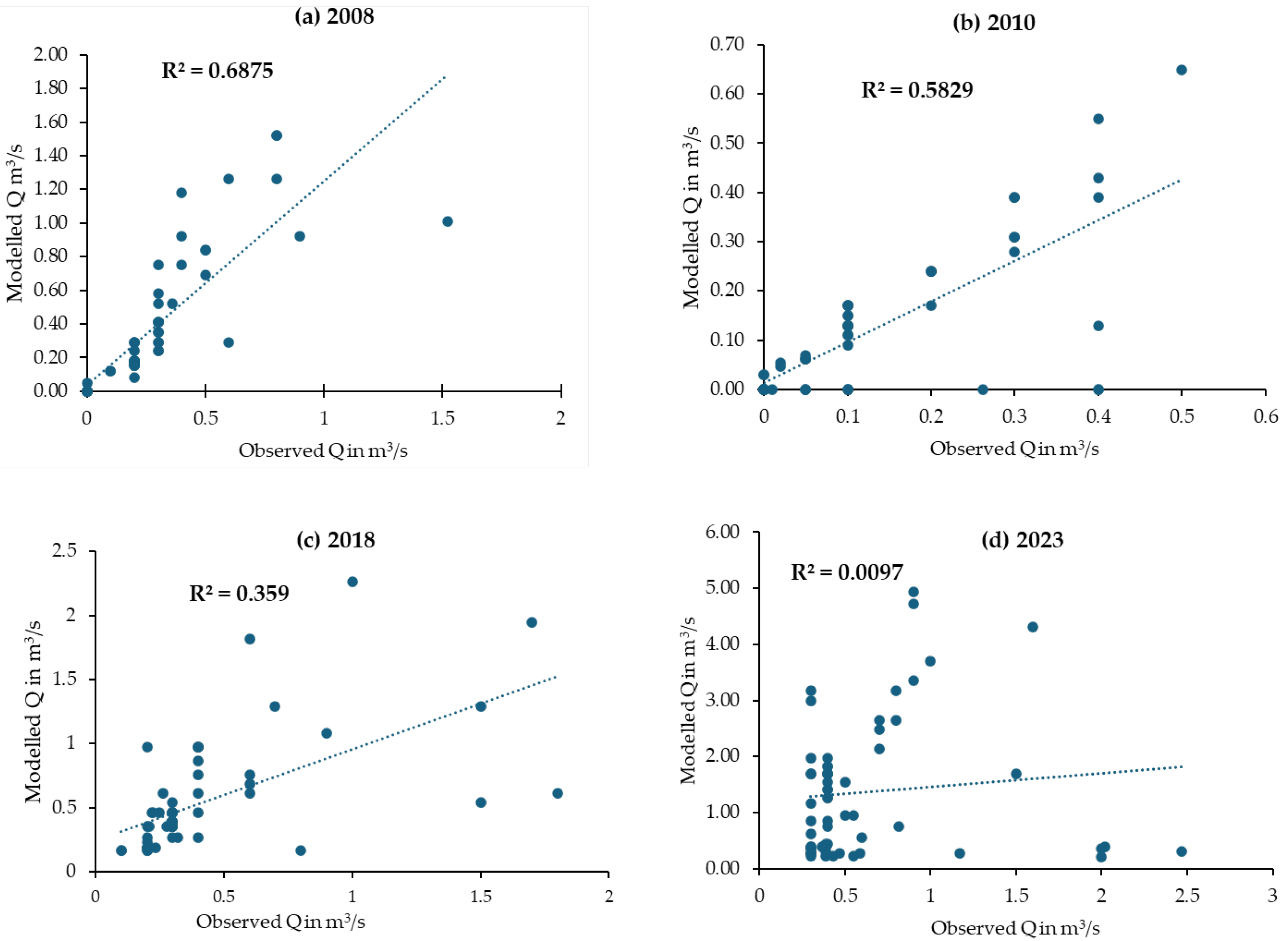

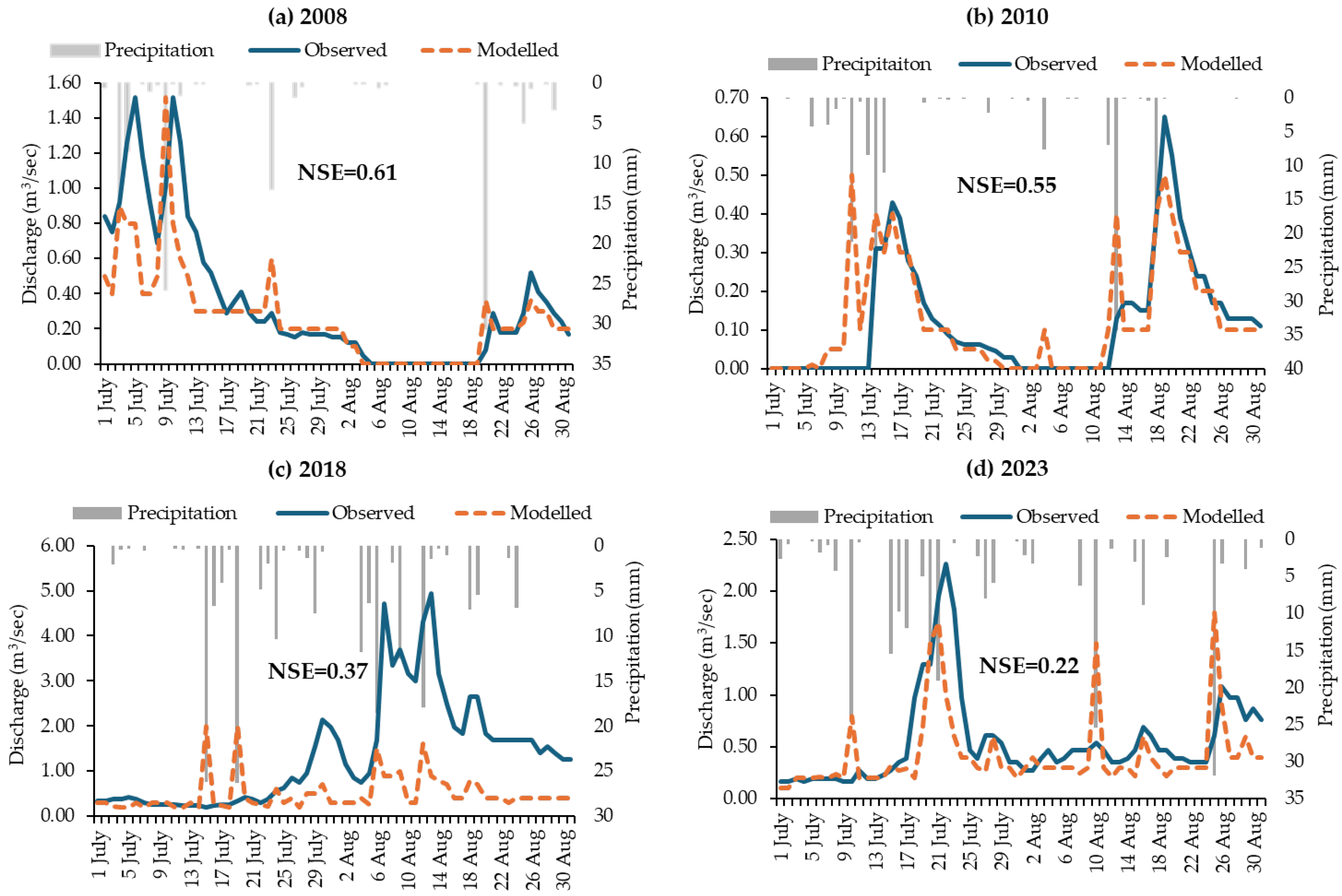

Figure 1. As shown in

Figure 4 and

Table 3, the results in 2008 and 2010 achieved satisfactory performance, with NSE values of 0.61 and 0.55 and R

2 values of 0.69 and 0.58, respectively. Percent bias indicated underestimation in 2008 (−25%) and slight overestimation in 2010 (+7%), while the RMSE values remained low (0.25 and 0.10 m

3/s), confirming acceptable error magnitudes. KGE values for these years (0.56 and 0.74) further indicate good agreement in terms of correlation, bias, and variability.

However, correlation and predictive accuracy declined in later years. In 2018, NSE dropped to 0.23 and R2 to 0.35, with PBIAS showing a −22% underestimation and RMSE increasing to 0.38 m3/s. The corresponding KGE value (0.50) suggests that although peak flows were underestimated, overall hydrological variability and correlation remained moderately represented. Performance deteriorated further in 2023, where NSE was −1.52 and R2 ≈ 0.01, accompanied by a large negative bias (−55%) and high RMSE (1.45 m3/s). The strongly negative KGE (−0.22) confirms a substantial mismatch between model assumptions and observed hydrological behavior under recent densification. Negative NSE values indicate that the model performed worse than the mean of the observed data, reflecting the limits of SUWMBA under rapidly changing land use conditions.

Several factors explain the deterioration in model performance in 2018 and 2023. First, rapid densification introduced informal hydrological pathways—such as shallow roadside channels, greywater discharge trenches, and wastewater leakage from pit latrines—that are not represented in the MUSIC rainfall–runoff structure. These unmodeled pathways altered flow routing and likely contributed to the systematic underestimation of peak flows. Second, discharge monitoring at the Selbe–Dambadarjaa station has become less consistent in recent years, resulting in data gaps and potential measurement uncertainty. Third, rapid construction between 2018 and 2023 created transitional surfaces (compacted soil, temporary structures, mixed pervious–impervious areas) that reduce infiltration and are difficult to classify accurately, introducing uncertainty into the land-cover inputs used for runoff simulation.

In addition, part of the reduced performance can be attributed to the representativeness of the precipitation data. The meteorological station and the gauging station are located at different elevations (approximately 1320 m and 1532 m, respectively), which may result in discrepancies between the recorded rainfall and the actual catchment conditions, particularly during localized convective storms. These mismatches become more pronounced under recent urban densification, where small-scale hydrological changes strongly influence runoff generation. Furthermore, both 2018 and 2023 experienced unusually high-intensity rainfall events that produced short-duration flood peaks. Under these extreme events, rainfall intensities exceeded the model’s calibration range, producing short-duration flood peaks and contributing to the underestimation of peak flows, including the strongly negative NSE observed in 2023. Despite these limitations, the model remains suitable for comparative scenario analysis, as relative differences between the baseline and redevelopment conditions are less sensitive to these uncertainties. Because MUSIC is calibrated for typical rainfall patterns rather than extreme storm events, these peaks were not adequately reproduced, contributing to the decline in NSE and R2 values in the later years. The degraded model performance in 2023 (NSE = −1.52) also affects the reliability of the comparative analysis across years, because several interpretations in this study draw on the 2023 model outputs. Since the model did not reproduce the observed runoff conditions well for this year, the estimated differences in stormwater runoff should be interpreted with caution. This limitation introduces additional uncertainty into the assessment of hydrological changes over time. Nevertheless, the scenario analysis remains informative because it evaluates the relative differences between the baseline and redevelopment conditions, which were less sensitive to systematic model bias than the absolute runoff estimates for 2023.

Hydrograph comparisons (

Figure 5) also illustrate these trends. While overall the simulations reproduced seasonal flow patterns and peak rainfall events reasonably well, simulations from 2018 onward underestimated peak flows and misrepresented baseflow. This decline likely reflects increasing complexity in urban hydrology due to densification, as well as limitations in monitoring data for newer developments.

4.3. SUWMBA Simulation Outputs

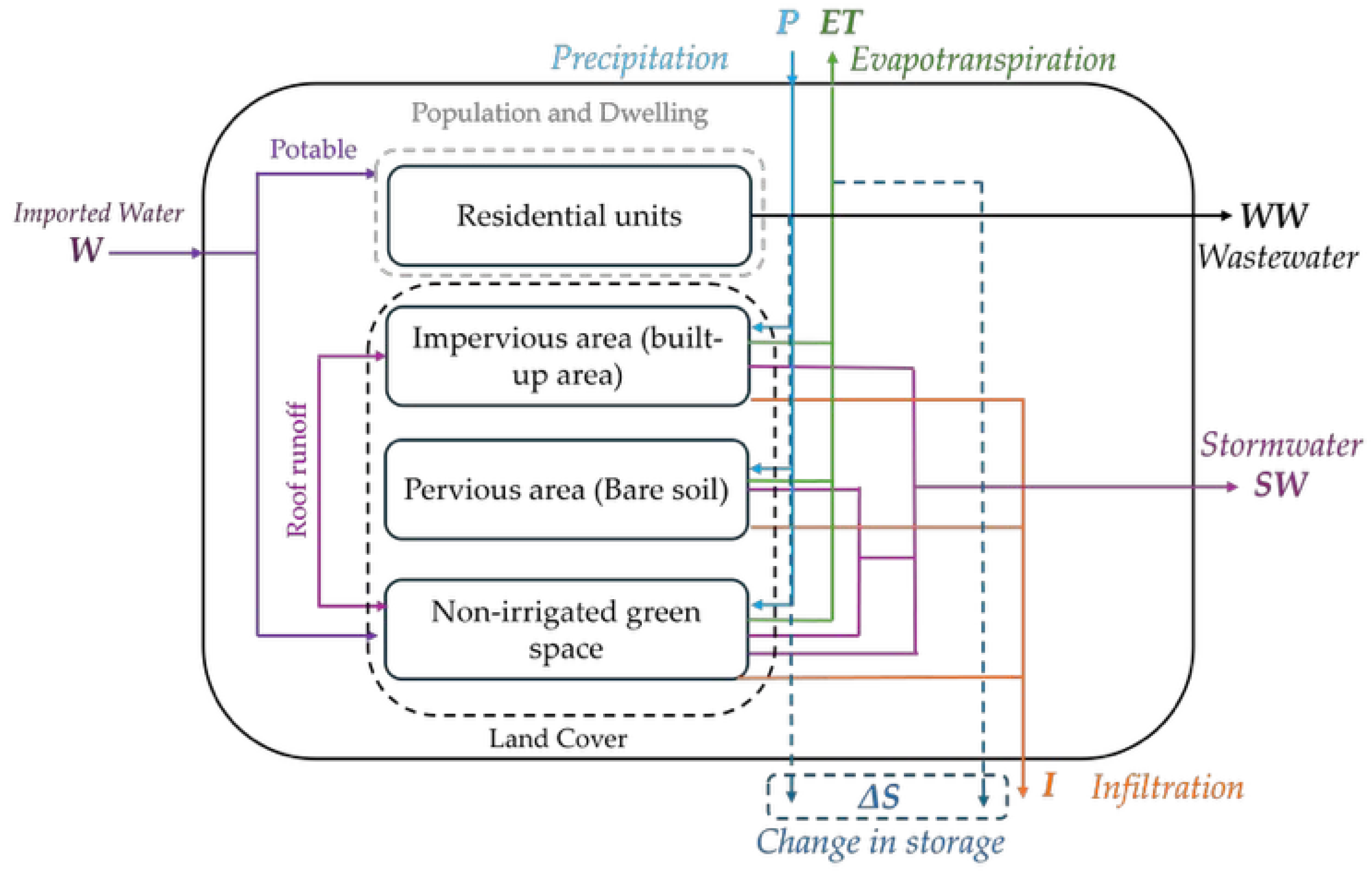

As shown in

Table 4, SUWMBA simulations for the 6.08 ha Selbe Sub-Center site revealed substantial alterations in the urban water cycle from 2008 to 2023, with runoff, evapotranspiration, infiltration, and imported water demand all reflecting the effects of densification and evolving land cover.

Relative to 2008, the total inflows increased by approximately 36% in 2010, 69% in 2018, and 83% in 2023, while total outflows increased by 24%, 57%, and 77%, respectively. Storage change (ΔS) shifted from a slight deficit in 2008 to positive values in later years, with the largest increases in 2010 and 2018 and a smaller increase in 2023. These percentage-based trends highlight the progressive intensification of the urban water cycle under densification.

From 2008 to 2023, total inflows increased from 223 to 312 mm, driven by a more than twentyfold rise in imported water (from 1 to 22 mm). Evapotranspiration declined by roughly 30%, while infiltration exhibited nonlinear, threshold-type responses to densification. Runoff increased steadily with the expansion of impervious surfaces, and wastewater exports rose in parallel with population growth.

These water balance outcomes reflect the absence of centralized water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure in the study area. Household water is obtained from local water kiosks rather than a piped network, so imported water (W) represents only this small on-site demand. Wastewater (WW) equals this volume because it is discharged locally to the soil, and all stormwater runoff (SW) is generated and retained on-site due to the lack of drainage infrastructure.

These shifts reflect reduced hydrological naturalness and increasing dependence on external water sources under redevelopment conditions. Even modest increases in imported water highlight vulnerability in ger redevelopment areas lacking centralized infrastructure. Declining ET and fluctuating infiltration indicate diminished ecosystem function, while rising runoff signals heightened flood risk. Collectively, these outputs demonstrate that densification without water-sensitive interventions exacerbates hydrological stress in cold, semi-arid urban environments.

4.4. Application of SUWMBA Framework to a Planning Project: Selbe Sub-Center Redevelopment

So far, water balance estimates have been made for 2008, 2010, 2018, and 2023. Meanwhile, a scenario based on the Feasibility Study of the Selbe Sub-Center Ger Residential Area Redevelopment and Housing Project [

36], which is one of the first initiatives under the Ulaanbaatar City Master Plan 2040 (Selbe Sub-Center redevelopment scenario) has been proposed [

37]. Therefore, we applied the SUWMBA framework to this project area to estimate the water mass balance.

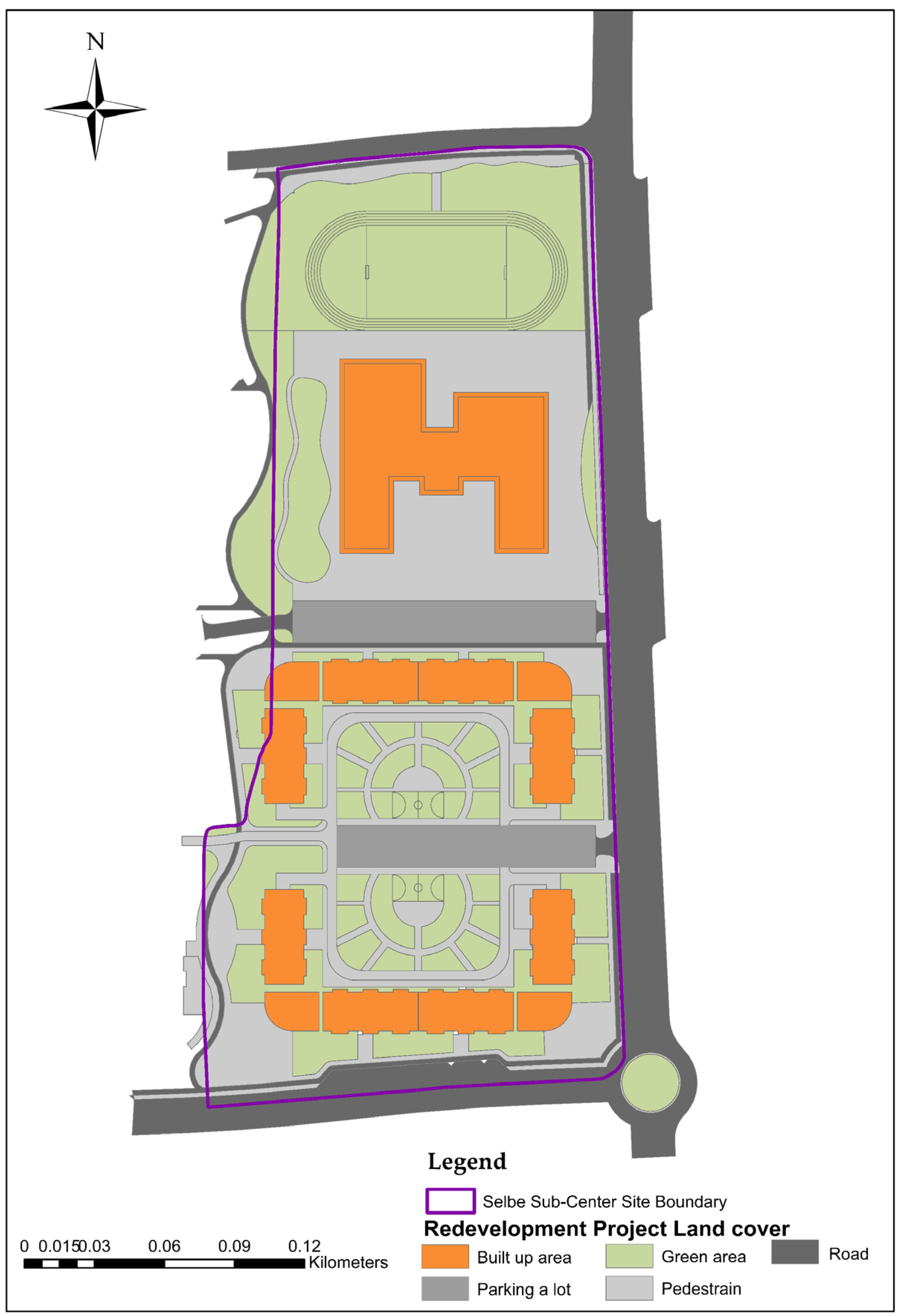

The Selbe Sub-Center redevelopment scenario involves transforming existing ger districts into higher density housing areas, accompanied by expanded water supply and sanitation infrastructure. Within the SUWMBA framework, this scenario was parameterized by adjusting land cover fractions, impervious area, and population density to reflect projected redevelopment conditions (

Figure 6). In addition to land cover changes, the redevelopment scenario also incorporates the introduction of centralized water, wastewater, and stormwater infrastructure, which substantially alters the water balance outcomes even under the same degree of imperviousness. It provides a forward-looking assessment of how planned densification will alter the urban water cycle, complementing the past and current situation results for 2008, 2010, 2018, and 2023.

In the Selbe Sub-Center redevelopment, land cover and demographic characteristics of the Selbe Sub-Center project area were adjusted to reflect planned densification under the Ulaanbaatar City Master Plan 2040. As shown in

Table 5, the total site area is 60,883 m

2, of which 12,849 m

2 is occupied by building footprints, 27,300 m

2 by roads, and 20,734 m

2 by green space. The scenario assumes a population of 804 residents accommodated within 8 multi-unit dwellings, representing a shift from low-density ger housing toward consolidated apartment blocks. These changes illustrate the transformation of land cover composition and settlement structure under the redevelopment plan.

For the redevelopment planning project, household water demand was set at 80 L/person/day in line with national norms for connected public housing. This represents a planning assumption reflecting the shift from ger households to fully serviced apartments. The imported water in

Table 6 is supplied from the Tuul River Basin via the city’s centralized network, while wastewater is exported to treatment facilities outside the Selbe Catchment. Within SUWMBA, these flows are represented as external boundary inputs and outputs rather than internal Selbe hydrological processes.

Table 6 summarizes the projected urban water mass balance components for the Selbe Sub-Center redevelopment scenario under the Ulaanbaatar City Master Plan 2040. Total inflows amount to 773 mm, consisting of 387 mm of precipitation and 386 mm of imported water supplied through the centralized system. Outflows total 780 mm, distributed across evapotranspiration (132 mm), stormwater runoff (270 mm), infiltration (24 mm), and wastewater export (386 mm). The resulting storage change is −7 mm, indicating a slight net loss of soil moisture under the densified land-use configuration.

Compared to the results obtained in 2008–2023 for the Selbe Sub-Center site, the redevelopment planning project scenario reflects reduced evapotranspiration and increased stormwater runoff, consistent with expanded impervious cover and diminished vegetation. These projections highlight the hydrological consequences of densification at the project scale, providing quantitative evidence of how redevelopment alters the balance between inflows, outflows, and storage.

Taken together, the simulations for years of 2008–2023 and the redevelopment scenario provide a comprehensive picture of how densification transforms the urban water cycle in the Selbe River Catchment. While the site results from 2008–2023 reveal declining hydrological naturalness and increasing reliance on imported water, the redevelopment scenario highlights further shifts anticipated under Master Plan 2040. Together, these findings set the stage for a broader discussion of implications for water-sensitive urban design and integrated land–water management in Ulaanbaatar.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates that land-use change in the densifying Selbe River Catchment has substantially altered the site-scale urban water cycle. Between 2008 and 2023, total inflows increased from 223 to 312 mm, driven largely by a more than twentyfold rise in imported water (from 1 to 22 mm). Evapotranspiration declined from 193 to 135 mm, while stormwater runoff rose from 29 to 77 mm in response to expanding impervious surfaces. Infiltration patterns were irregular, reflecting threshold-type soil–vegetation interactions that can temporarily buffer hydrological impacts. Collectively, these shifts indicate reduced hydrological naturalness and increasing dependence on external water sources. The decline in evapotranspiration further underscores the importance of urban greenery strategies, which are known to improve microclimates and support ecosystem function in cold, semi-arid urban environments [

37].

Earlier hydrological experiments in the Selbe River Catchment [

27] emphasized natural rainfall–runoff variability, with evapotranspiration losses reaching up to 90% in dry months. The present SUWMBA analysis extends this baseline by quantifying how redevelopment intensifies stress, shifting the balance from precipitation-dominated to infrastructure-dependent water systems. This trajectory mirrors findings from other rapidly urbanizing regions, where densification outpaces infrastructure expansion and forces reliance on distant water sources that are environmentally costly and economically unsustainable [

38]. Comparable system dynamics modeling in Indonesia has similarly highlighted how integrated approaches are needed to manage clean water under rapid urbanization [

39].

To situate these findings within broader research on Ulaanbaatar’s water security,

Table 7 compares the Selbe SUWMBA case with recent catchment- and city-scale studies. While previous work has focused on water yield modeling, groundwater contamination, managed aquifer recharge, and governance diagnostics, this study provides the first site-scale quantification of hydrological transformation under planned redevelopment.

These comparisons highlight that while basin- and city-scale studies have advanced the understanding of water yield, groundwater contamination, recharge strategies, and governance, none have quantified site-scale hydrological performance under redevelopment. The Selbe SUWMBA case therefore fills a critical methodological gap, providing evidence that densification without water-sensitive interventions reduces hydrological naturalness and exacerbates stress on urban water systems. The nature-based solutions literature identifies indicators and barriers relevant to embedding ecological functions into redevelopment [

43], while blue-green infrastructure reviews emphasize that design and planning choices strongly influence hydrological resilience in densifying cities [

44].

Policy implications are clear: Ulaanbaatar’s Master Plan 2040 must embed Water Sensitive Urban Design measures—such as permeable pavements, green roofs, rainwater harvesting, and regenerative landscaping—to ensure that redevelopment enhances resilience rather than amplifying vulnerability. Regional climate studies highlight that semi-arid cities face increasing extremes, intensifying the urgency of water-sensitive planning [

35].

Limitations of this study include the decline in model performance after 2018 and the reliance on available monitoring data, which may not fully capture informal water pathways. Model performance deteriorated markedly after 2018 due to rapid densification, increasing imperviousness, and the emergence of informal drainage routes that are not represented within SUWMBA’s fixed-parameter framework. During this period, the Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) became increasingly sensitive to peak-flow underestimation, whereas the Kling–Gupta Efficiency (KGE) provided a more balanced evaluation by integrating correlation, bias, and variability. The moderate KGE in 2018 (0.50) and the strongly negative value in 2023 (−0.22) indicate that hydrological behavior diverged progressively from the model assumptions as redevelopment intensified. These findings highlight the need for improved monitoring data and the adoption of dynamic or hybrid modeling approaches in future work to better represent evolving urban hydrological processes.

In adapting international WSUD approaches to Ulaanbaatar, it is essential to recognize Mongolia’s unique climatic and socio-economic constraints. Cold-climate conditions—including frozen soils for five to six months, limited infiltration during winter, delayed spring snowmelt, and short vegetation growth periods—restrict the year-round performance of green infrastructure and require modified design standards. At the same time, socio-economic realities in ger areas, such as low household income, informal land tenure, and limited capacity for operation and maintenance, influence the feasibility and long-term adoption of WSUD measures. These factors highlight that while global initiatives such as Sponge Cities and Low Impact Development offer valuable frameworks, their implementation in Ulaanbaatar must be tailored to local climatic and community conditions to ensure effectiveness and equity.

In addition to freeze–thaw-resilient WSUD measures, Ulaanbaatar’s hydrology offers opportunities for seasonal storage and managed aquifer recharge (MAR). Because infiltration is limited during winter but increases rapidly during spring thaw, the most feasible recharge window aligns with the short, high-flow snowmelt period. Potential strategies include shallow infiltration galleries, controlled recharge basins, and the use of green open spaces for temporary detention during meltwater pulses. These approaches allow excess spring runoff to be stored underground for later use, reducing pressure on centralized supply systems and enhancing resilience in a highly seasonal climate.

Cold semi-arid hydrological dynamics further shape the feasibility of WSUD in Ulaanbaatar. Prolonged soil freezing suppresses infiltration for much of the year, while rapid spring snowmelt generates short, intense runoff pulses that place additional pressure on drainage systems. These conditions require tailored WSUD solutions such as insulated rainwater harvesting tanks, frost-resistant infiltration trenches, permeable pavements designed for freeze–thaw cycles, and snow-compatible stormwater conveyance. Socio-economic considerations are equally important: many ger-area households face financial constraints, variable land tenure, and limited capacity for system upkeep, making the long-term sustainability of WSUD dependent on cost–benefit trade-offs, community engagement, and affordable maintenance pathways. Integrating these climatic and socio-economic realities is essential for designing WSUD interventions that are both technically viable and socially equitable in Mongolia’s redevelopment context.

By applying SUWMBA in a cold semi-arid, developing-country context, this study establishes methodological precedent and provides quantitative evidence for embedding water-sensitive design into Mongolia’s decentralization strategy. Planetary health frameworks stress that safeguarding water systems is central to resilience in the Anthropocene [

45].

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the application of the site-scale Urban Water Mass Balance Assessment (SUWMBA) framework to quantify hydrological transformations under land use change in the Selbe River Catchment, Ulaanbaatar. Results revealed a sharp rise in imported water dependency, declining evapotranspiration, irregular infiltration responses, and steadily increasing stormwater runoff. These findings demonstrate how densification without water-sensitive interventions reduces hydrological naturalness and intensifies stress on urban water systems in cold semi-arid contexts.

By situating the Selbe case alongside catchment- and city-scale studies, this research fills a critical methodological gap: it provides the first site-scale quantification of hydrological performance under planned redevelopment in Mongolia. The evidence underscores the need to embed Water-Sensitive Urban Design measures—such as permeable pavements, green roofs, rainwater harvesting, and regenerative landscaping—into Ulaanbaatar’s Master Plan 2040 and National Development Concept 2050. Doing so will ensure that redevelopment enhances resilience rather than amplifying vulnerability.

Beyond its local relevance, this study establishes methodological precedent for applying SUWMBA in developing-country urban systems with incomplete infrastructure. Future work should integrate socio-economic variables, expand the monitoring of informal water pathways, and test WSUD interventions at site-scale. Together, these efforts will advance integrated land–water management strategies and support more sustainable urban transformation in Mongolia and comparable semi-arid cities worldwide.