At Risk While on the Move—Mobility Vulnerability of Individuals and Groups in Disaster Risk Situations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Systematic Literature Review

3.2. Findings Within Selected Studies

3.3. Summary of Key Findings

3.4. Development of a Mobility Vulnerability Framework

3.4.1. From Static to Situational

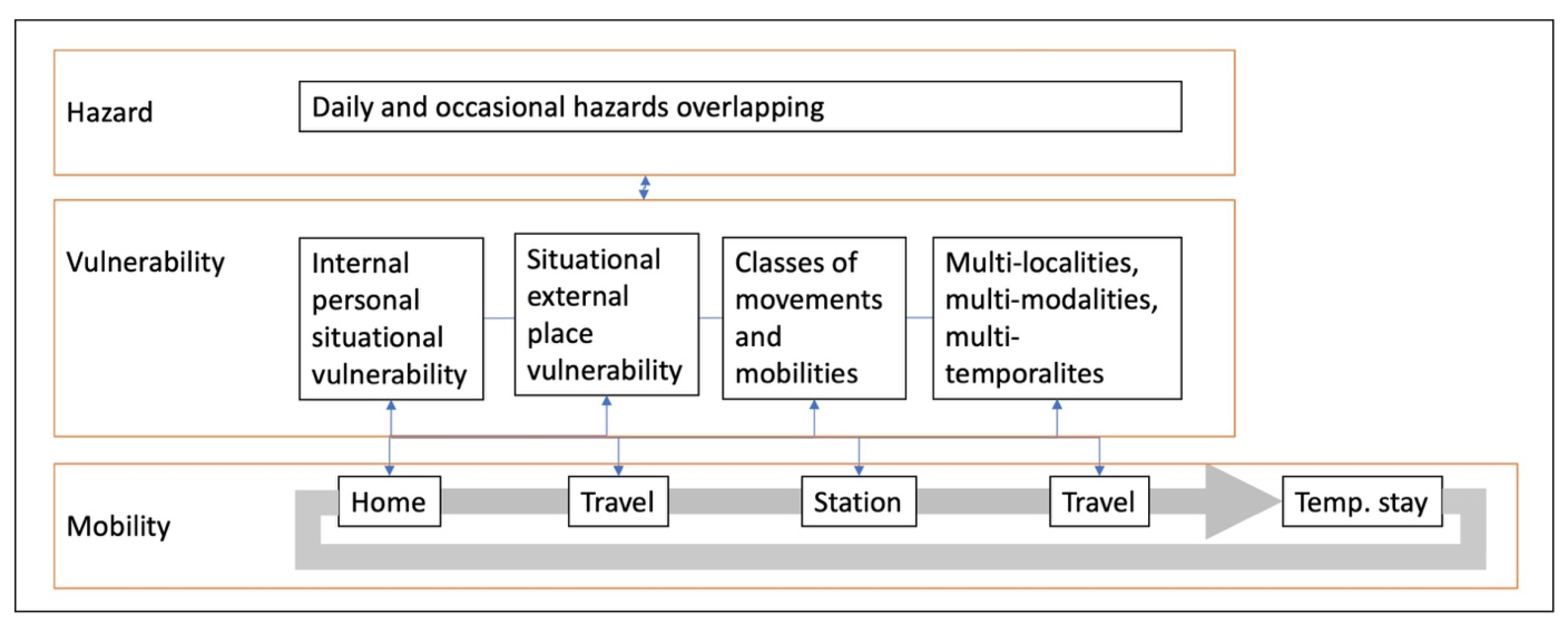

3.4.2. Sequences of Stationary and Mobility Vulnerability Patterns

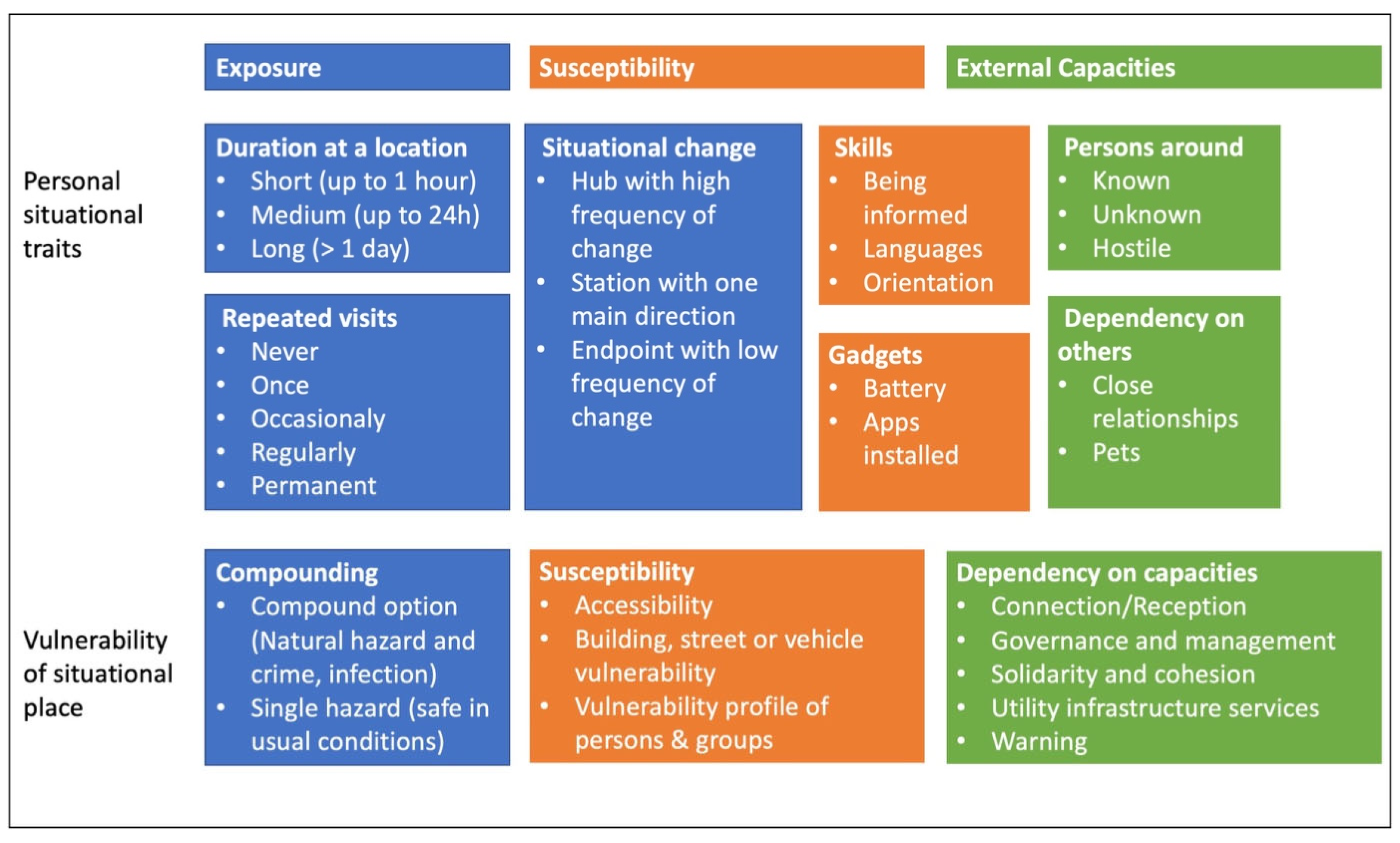

3.4.3. Personal and Situational Vulnerability Components

- Integrating

- Disaster risk and impact situations

- Classes of movements and mobilities related to disaster risk situations

- Multi-localities, multi-modalities, multi-temporalities, and multiple risks during sequences of movement and stationary situations

- Daily and occasional hazards

- Emic and etic characteristics of vulnerability

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of This Study

4.2. Can You Leave ‘Your Own Vulnerability’ Behind

5. Conclusions

- i.

- Research recommendations: a focus on science and future vulnerability assessments, which include studies of vulnerability not only at specific locations but also in between, as well as for the specific variables and indicators related to mobility. As the second part of this study, it presents conceptual criteria that could be considered in such an assessment of mobility vulnerability: first, recognising the situation and the moving window of time and exposure. Second, to integrate different studies on the location of origin and destination, and the stations in between, as well as the corridors of movement of individuals and groups of people. To address this, it is also necessary to consider the typical conceptual dimensions of vulnerabilities, including exposure, susceptibility, and capacities.

- ii.

- Policy/practice recommendation: recognise the necessity of planning for risks while people are travelling, in transition, or especially during disaster situations, such as evacuation. Risks, exposure, and specific susceptibilities must be planned for in advance, and assistance provided during such mobilities, as well as in the recovery process and aftercare.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Term | Title-Abs-Keys | Title-Abs-Keys Review Papers | Title Search | Title Search Review Papers | Excl No Abs | Excl Dupl | Excl No Fit | Excl Redund. Info |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * home | 12,140 | 859 | 296 | 7 | ||||

| Vulnerab * travel | 3235 | 177 | 50 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * destination | 1464 | 78 | 20 | 0 | ||||

| Hub | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * airport | 338 | 14 | 6 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * border | 2841 | 154 | 69 | 1 | ||||

| Vulnerab * train station | 150 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * mobility infrastructure | 344 | 22 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Means of transportation | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * bicycle | 393 | 16 | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * bus | 1432 | 16 | 14 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * car | 1335 | 88 | 15 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * subway | 282 | 5 | 12 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * taxi | 118 | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * train | 14,041 | 906 | 125 | 4 | ||||

| Vulnerab * truck | 294 | 14 | 12 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * plane | 1657 | 54 | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * boat | 398 | 16 | 4 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * ferry | 57 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * ship | 1101 | 57 | 57 | 0 |

| Search Term | Social Group | Mobility Context | Hazard or Driver | Research Field | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulnerab * mobility | Households | Transportation environment | Terrorism | Urban geography | [29] |

| Social Vulnerab * mobility | Communities | Income, transportation | Transportation challenges | Occupation | [26] |

| Social Vulnerab * mobility | Domestic workers, flight crews, and sailors | Travel | COVID-19 | Public health | [30] |

| “mobility vulnerability” | Census blocks | Human mobility, mobile phone data | COVID-19 | Travel | [25] |

| Vulnerable mobil * group | Households, elderly, lower socioeconomic status | Foot traffic | Snowstorm | Natural hazards | [31] |

| Vulnerab * evacuation | Household, females, seniors | Mass evacuation, | Flood | Transport | [32] |

| Vulnerab * evacuation | Elderly | Host communities | Wildfire | Society | [33] |

| Vulnerab * evacuation | Drivers | Driving during emergency evacuation | Emergencies | Planning | [38] |

| Vulnerab * transit | Neighbourhoods | Access and waiting | Heat | Transport | [34] |

| Vulnerab * transit | Passengers | Bus ride | Black carbon exposure | Transport | [42] |

| Vulnerab * transit | Vulnerable commuters, riders | Public transit | Crime | Security | [43] |

| Vulnerab * Occupation | Professions | Job activities | Climate change | Sustainability | [35] |

| Vulnerab * Migrant | Migrants | Crossing a mountainous rainforest region | Migration, abuse, exploitation, malnourishment | Medicine | [40] |

| Social Vulnerab * mobility framework | People | Climate mobility | Climate extreme events | Geography | [41] |

| Vulnerab * mobility nighttime | Urban population | Diurnal migration in day and nighttime | Heat, flood | Health, Communications | [36,37] |

Details on Exclusion for Further Screening and Analysis

References

- Montz, B.E.; Tobin, G.A.; Hagelman, R.R. Natural Hazards: Explanation and Integration; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L. (Ed.) What is a Disaster? Perspectives on the Question; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; pp. 234–273. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cuny, F.C. Disasters and Development; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, D.P. Introduction to International Disaster Management, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.F.; Kates, R.W.; Burton, I. Knowing better and losing even more: The use of knowledge in hazards management. Environ. Hazards 2001, 3, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.F. Human Adjustment to Floods: A geographical Approach to the Flood Problem in the United States; The University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A place-based model for understanding community resilience. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, A.; O’Keefe, P.; Westgate, K.N.; Wisner, B. Towards an Explanation and Reduction of Disaster Proneness; Occasional paper no.11; Disaster Research Unit.; University of Bradford: Bradford, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. At Risk—Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K.; Zakieldeen, S.A. Loss and Damage Due to Climate Change. An Overview of the UNFCCC Negotiations; European Capacity Building Initiative: Oxford, UK, 2012; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Synthesis Report. Longer Report; The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. In A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change-IPCC; Field, C.B., Barros, V., Stocker, T.F., Dahe, Q., Dokken, D.J., Ebi, K.L., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Plattner, G.-K., Allen, S.K., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Armaș, I.; Albulescu, A.-C. From static to dynamic: Conceptual and operational developments of vulnerability. IScience 2025, 28, 112070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ruiter, M.C.; Van Loon, A.F. The challenges of dynamic vulnerability and how to assess it. IScience 2022, 25, 104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nes, E.H.; Scheffer, M.; Brovkin, V.; Lenton, T.M.; Ye, H.; Deyle, E.; Sugihara, G. Causal feedbacks in climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcher, J.C.; Bates, F.L. Aftermath of natural disasters: Coping through residential mobility. Disasters 1983, 7, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow-Jones, H.A.; Morrow-Jones, C.R. Mobility Due to Natural Disaster: Theoretical Considerations and Preliminary Analyses. Disasters 1991, 15, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, U.; Arnall, A.; Azfa, A. Disaster mobilities, temporalities, and recovery: Experiences of the tsunami in the Maldives. Disasters 2023, 47, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, N. Forced Relocation After the Indian Ocean Tsunami 2004—Case Study of Vulnerable Populations in Three Relocation Settlements in Galle, Sri Lanka; UNU-EHS: Bonn, Germany, 2012; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Renaud, F.; Bogardi, J.J.; Dun, O.; Warner, K. Control, Adapt or Flee. How to Face Environmental Migration? UNU-EHS: Bonn, Germany, 2007; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K.; Hamza, M.; Oliver-Smith, A.; Renaud, F.; Julca, A. Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Nat. Hazards 2010, 55, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lu, Y. Exploring dual-directional collective human mobility vulnerability and the built environment in places: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Travel Behav. Soc. 2025, 40, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeghers, M.; Winter, S.; Classen, S. Exploring Transportation Challenges and Opportunities for Mobility-Vulnerable Populations Through the Social-Ecological Model. OTJR-Occup. Ther. J. Res. 2025, 45, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, K. Place ontologies and a new mobilities paradigm for understanding awareness of vulnerability to terrorism in American cities. Urban Geogr. 2014, 35, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.J.; Alipio, C.; Wan, J.A.; Mane, H.; Nguyen, Q.C. Social Network Analysis on the Mobility of Three Vulnerable Population Subgroups: Domestic Workers, Flight Crews, and Sailors during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhai, W.; Yang, X.K. Enhancing resilience and mobility services for vulnerable groups facing extreme weather: Lessons learned from Snowstorm Uri in Harris County, Texas. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 1573–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.J.; Habib, M.A. Vulnerability Assessment during Mass Evacuation: Integrated Microsimulation-Based Evacuation Modeling Approach. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, H.W.; McGee, T.K.; Christianson, A.C. Indigenous Elders’ Experiences, Vulnerabilities and Coping during Hazard Evacuation: The Case of the 2011 Sandy Lake First Nation Wildfire Evacuation. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.M.; Chester, M.V. Transit system design and vulnerability of riders to heat. J. Transp. Health 2017, 4, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, H.; Lim, U. Exploring the Spatial Distribution of Occupations Vulnerable to Climate Change in Korea. Sustainability 2016, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.C.; Tong, S.L.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, K.J.; Yang, X.C.; Yang, Y.J. Mapping Heat Vulnerability and Heat Risk for Neighborhood Health Risk Management in Urban Environment? Challenges and Opportunities. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2025, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.Y.; Duan, H.F. Human mobility amplifies compound flood risks in coastal urban areas under climate change. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, O.F.; Dulebenets, M.A.; Ozguven, E.E.; Moses, R.; Boot, W.R.; Sando, T. Assessing perceived driving difficulties under emergency evacuation for vulnerable population groups. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 72, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawano, T.; Nishikawa, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Leppold, C.; Takiguchi, M.; Saito, H.; Shimada, Y.; Morita, T.; Tsukada, M.; Ohira, H.; et al. Premature death associated with long-term evacuation among a vulnerable population after the Fukushima nuclear disaster A case report. Medicine 2019, 98, e16162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, L.; Williams, Y.; Levy, J.; Obando, R.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Pachar, M.; Chen, R.D.R.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Higuita, N.A.; Henao-Martinez, A.; et al. The Endless Vulnerability of Migrant Children In-Transit across the Darien Gap. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 109, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarun; Cooke, B.; Vahanvati, M.; McEvoy, D. Rethinking Climate Extreme Events and (Im)mobility From a Place-Based Perspective. Geogr. Compass 2025, 19, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.; Bosker, T.; Dirks, K.N.; Behrens, P. The impact of seating location on black carbon exposure in public transit buses: Implications for vulnerable groups. Transp. Res. Part D-Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.S.V.; Smith, M.J. Commuters using public transit in New York City: Using area-level data to identify neighbourhoods with vulnerable riders. Secur. J. 2014, 27, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sherbinin, A. Mapping the Unmeasurable? Spatial Analysis of Vulnerability to Climate Change and Climate Variability; University of Twente: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, O.D. Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment; Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Seismology: Skopje, North Macedonia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, R.A.; Shah, H.C. An Urban Earthquake Disaster Risk Index; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, G.A.; Montz, B.E. Natural Hazards. Explanation and Integration; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elvidge, C.D.; Safran, J.; Tuttle, B.; Sutton, P.; Cinzano, P.; Pettit, D.; Arvesen, J.; Small, C. Potential for global mapping of development via a nightsat mission. GeoJournal 2007, 69, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, W.; He, C.; Yu, B.; Li, X.; Elvidge, C.D.; Cheng, W.; Zhou, C. Applications of satellite remote sensing of nighttime light observations: Advances, challenges, and perspectives. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, O.; Wilson, D.; Bent, R.; Linger, S.; Arnold, J. Accuracy of Service Area Estimation Methods Used for Critical Infrastructure Recovery. In Critical Infrastructure Protection VIII: 8th IFIP WG 11.10 International Conference, ICCIP 2014, Arlington, VA, USA, 17–19 March 2014; Revised Selected Papers; Butts, J., Shenoi, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Spiers, J. New perspectives on vulnerability using emic and etic approaches. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rufat, S.; Fekete, A. Conclusions of the First European Conference on Risk Perception, Behaviour, Management and Response; University of Cergy-Pontoise: Paris, France, 2019; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, H. Comprehensive Emergency Management. A Governor’s Guide; National Governors’ Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1979; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Kasperson, R.E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H.S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Kasperson, J.X.; Ratick, S. The Social Amplification of Risk: A Conceptual Framework. Risk Anal. 1988, 8, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappes, M.S.; Keiler, M.; von Elverfeldt, K.; Glade, T. Challenges of analyzing multi-hazard risk: A Review. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 1925–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, T.D.; Pelling, M.; Ghosh, A.; Matyas, D.; Siddiqi, A.; Solecki, W.; Johnson, L.; Kenney, C.; Johnston, D.; Du Plessis, R. Pathways for Transformation: Disaster Risk Management to Enhance Resilience to Extreme Events. J. Extrem. Events 2016, 03, 1671002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderbauer, S.; Baunach, D.; Pedoth, L.; Renner, K.; Fritzsche, K.; Bollin, C.; Pregnolato, M.; Zebisch, M.; Liersch, S.; Rivas López, M.d.R. Spatial-explicit climate change vulnerability assessments based on impact chains. Findings from a case study in Burundi. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; McCarthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Christensen, L.; Eckley, N.; Kasperson, J.X.; Luers, A.; Martello, M.L.; et al. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, J.; Cardona, O.D.; Carreño, M.L.; Barbat, A.H.; Pelling, M.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Kienberger, S.; Keiler, M.; Alexander, D.; Zeil, P.; et al. Framing vulnerability, risk and societal responses: The MOVE framework. Nat. Hazards 2013, 67, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrill, C.D.; Brooke, S.; Mulley, C.; Nelson, J.D.; Wright, S. Can multi-modal integration provide enhanced public transport service provision to address the needs of vulnerable populations? Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.B.; Gotham, J.C. Multi-modal mass evacuation in upstate New York: A review of disaster plans. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2007, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, D.; Wurm, M.; Stark, T.; Angelo, P.; Stebner, K.; Dech, S.; Taubenböck, H. Spatial parameters for transportation: A multi-modal approach for modelling the urban spatial structure using deep learning and remote sensing. J. Transp. Land Use 2021, 14, 777–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderbauer, S. Risk and Vulnerability to Natural Disasters—From Broad View to Focused Perspective. Doctoral Thesis, FU Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNDRR. Terminology. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/terminology (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Anderson, M.B.; Woodrow, P.J. Rising From the Ashes: Development Strategies in Times of Disaster, 1998th ed.; Lynne Rienner: Boulder, CO, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bohle, H.-G. Vulnerability and Criticality. In Newsletter of the International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change; Nr. 2/2001; Vulnerability Article 1; UNU-EHS: Bonn, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Manyena, S.B. The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters 2006, 30, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripley, A. The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes-and Why; Arrow: Centennial, CO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi, S.M.; Peerenboom, J.P.; Kelly, T.K. Identifying, Understanding, and Analyzing Critical Infrastructure Interdependencies. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2001, 21, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- UN/HABITAT. HABITAT III. New Urban Agenda; United Nations Human Settlement Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Form, W.H.; Nosow, S. Community in Disaster; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1958; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, K. (Ed.) Interpretations of Calamity. From the Viewpoint of Human Ecology; Allen & Unwin: Boston, MA, USA; London, UK; Sydney, Australia, 1983; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; De Campos, R.S.; Mortreux, C. Mobility, displacement and migration, and their interactions with vulnerability and adaptation to environmental risks. In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Displacement and Migration; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, C.A.; Slack, T.; Singelmann, J. Social vulnerability and migration in the wake of disaster: The case of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Popul. Environ. 2008, 29, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raška, P.; Dolejš, M.; Pacina, J.; Popelka, J.; Píša, J.; Rybová, K. Review of current approaches to spatially explicit urban vulnerability assessments: Hazard complexity, data sources, and cartographic representations. GeoScape 2020, 14, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, R.; Kuhlicke, C. Climate Captivity: When in-situ Adaptation and Moving Out Are No Longer Options. Prog. Environ. Geogr. 2025; Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakes, O.; Tate, E. Social vulnerability in a multi-hazard context: A systematic review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 033001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuohy, R.; Stephens, C. Exploring older adults’ personal and social vulnerability in a disaster. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2011, 8, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rufat, S.; Fekete, A.; Enderlin, E. Addressing the social vulnerability gap in disaster risk perception. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 129, 105789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, T.T. Global Policy of ‘Community of Common Destiny’and IR4: A Robust for Multiculturalism and Humanitarian Crisis Response. J. Public Value 2022, 6, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.H. Communities in Disaster. A Sociological Analysis of Collective Stress Situations; Doubleday: Garden City, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bankoff, G.; Frerks, G.; Hilhorst, D. Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development and People; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Longley, P.; Goodchild, M.F.; Maguire, D.J.; Rhind, D.W. Geographic Information Science and Systems, 4th ed.; Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J. Conway’s game of life. Sci. Am. 1970, 223, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Von Neumann, J.; Burks, A.W. Theory of self-reproducing automata. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1966, 5, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rufat, S.; Tate, E.; Emrich, C.T.; Antolini, F. How valid are social vulnerability models? Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 1131–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouilloud, J.-P. From “Crisisology” to “Riskology”. Communications 2012, 91, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, D. Disaster Theory: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Concepts and Causes; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Search Term | Title-Abs-Keys | Title-Abs-Keys Review Papers | Title Search | Title Search Review Papers | Excl No Abs | Excl Dupl | Excl No Fit | Excl Redund. Info |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General topic | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * mobility | 4579 | 288 | 89 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Social Vulnerab * mobility | 1261 | 78 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | |

| “Mobility vulnerability” | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | |||

| Social Vulnerab * mobility framework | 171 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 17 | |||

| Group type | ||||||||

| Vulnerability mobil * individual | 748 | 49 | 1 | 0 | 50 | |||

| Vulnerability mobil * person | 180 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | ||

| Vulnerability mobil * group | 848 | 52 | 2 | 0 | 54 | |||

| Vulnerable mobil * group | 1604 | 183 | 5 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Vulnerability mobil * crowd | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | |||

| Process | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * evacuation | 1250 | 68 | 58 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 49 | |

| Vulnerab * relocate * | 1012 | 59 | 13 | 0 | 13 | |||

| Vulnerab * transit | 1116 | 40 | 57 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 49 | |

| Livelihood | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * commuter | 131 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Vulnerab * farmer | 4596 | 333 | 169 | 3 | ||||

| Vulnerab * mobility farmer | 59 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 8 | |||

| Vulnerab * flight crews | 19 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Vulnerab * Fisher | 1196 | 46 | 19 | 0 | 19 | |||

| Vulnerab * Sailor | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 1 | ||

| Vulnerab * Shepherd | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 34 | |||

| Vulnerab * Nomad | 49 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | |||

| Vulnerab * Occupation | 1746 | 106 | 13 | 0 | 12 | |||

| Vulnerab * labor mobility | 270 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Leisure | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * Tourist | 938 | 31 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 20 | ||

| Vulnerab * Tourist evacuation | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | |||

| Vulnerab * Traveller | 356 | 38 | 9 | 0 | 9 | |||

| Disaster terms | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * Displaced | 1397 | 119 | 23 | 0 | 7 | 16 | ||

| Vulnerab * Homeless | 1880 | 154 | 120 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Vulnerab * Migrant | 4374 | 291 | 270 | 7 | 6 | |||

| Vulnerab * Refugee | 2750 | 278 | 134 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Situations | ||||||||

| Vulnerab * mobility daytime | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Vulnerab * mobility nighttime | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Vulnerab * mobility unfamiliar * | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |||

| Vulnerab * mobility situate * | 260 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |||

| Vulnerab* mobility situatedness | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Vulnerab * mobility disaster | 274 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | |||

| Vulnerab * mobility hazard | 295 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fekete, A. At Risk While on the Move—Mobility Vulnerability of Individuals and Groups in Disaster Risk Situations. Geographies 2025, 5, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040056

Fekete A. At Risk While on the Move—Mobility Vulnerability of Individuals and Groups in Disaster Risk Situations. Geographies. 2025; 5(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleFekete, Alexander. 2025. "At Risk While on the Move—Mobility Vulnerability of Individuals and Groups in Disaster Risk Situations" Geographies 5, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040056

APA StyleFekete, A. (2025). At Risk While on the Move—Mobility Vulnerability of Individuals and Groups in Disaster Risk Situations. Geographies, 5(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/geographies5040056