Investigation of Educational Needs of Primary Health Care Professionals in Greece for the Management of Adolescent Addictive Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Measurement Tools

2.3. Data Collection Procedure and Ethics

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

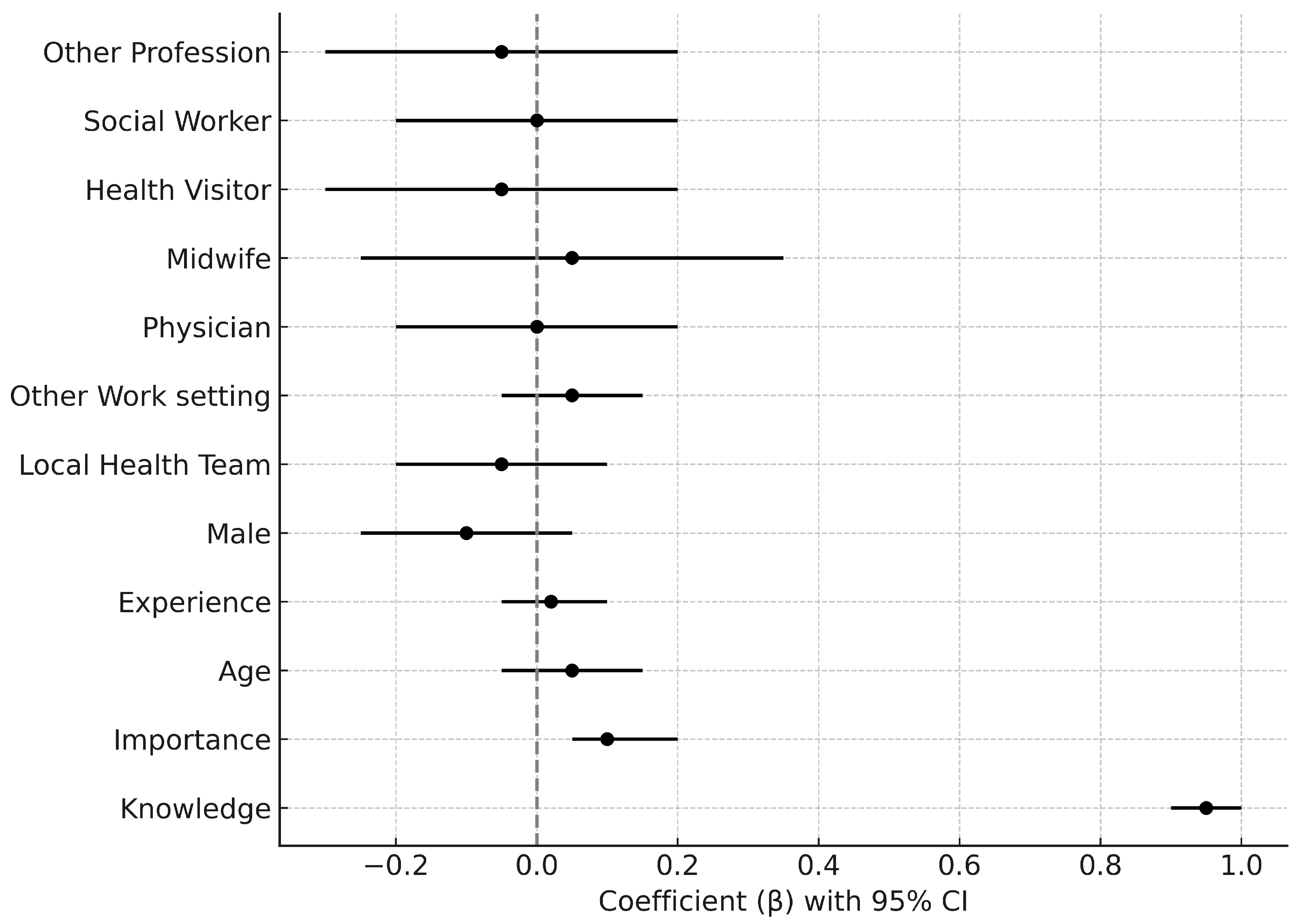

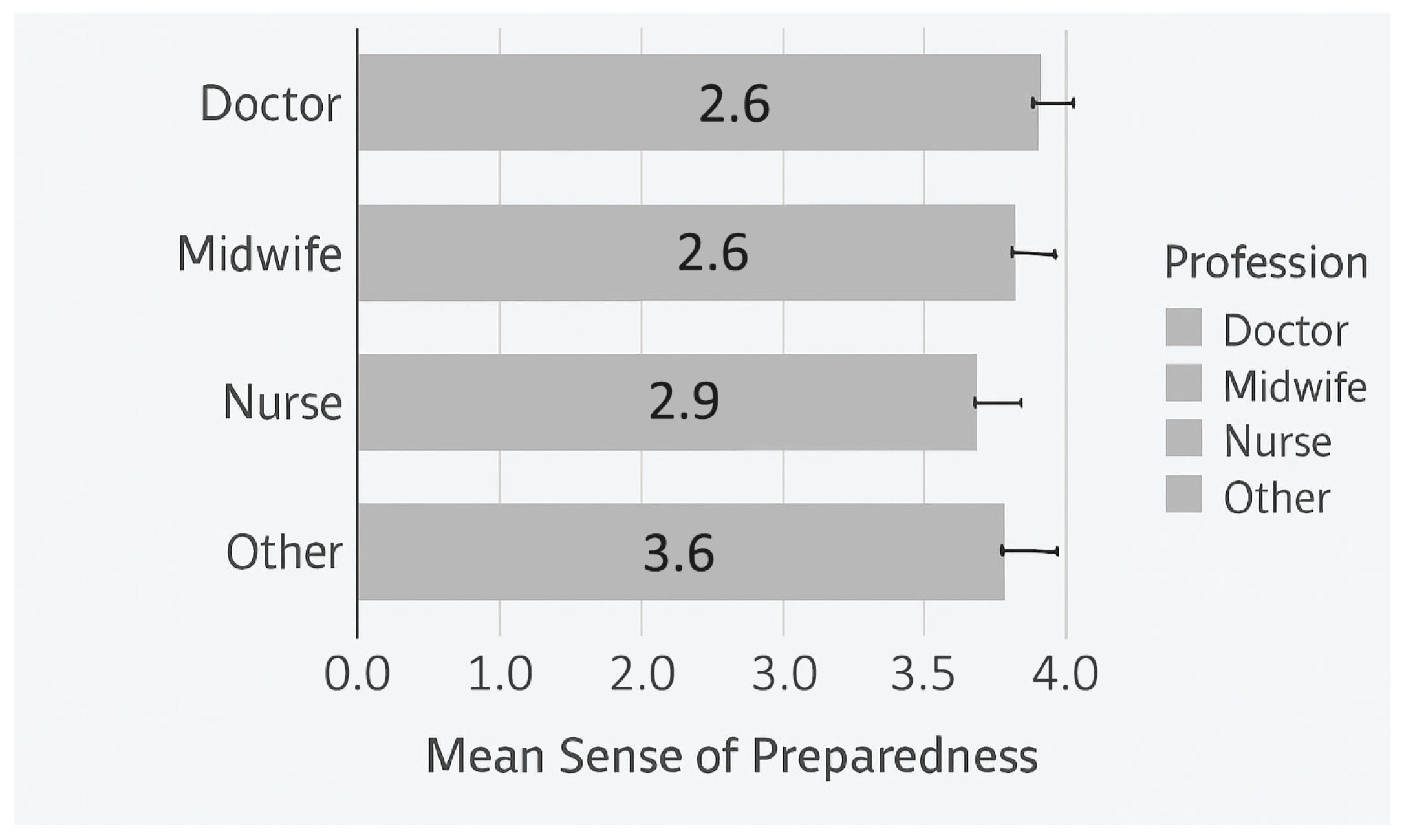

Key Adjusted Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. The Importance-Readiness Discrepancy and Its International Relevance

4.2. The Role of Knowledge, Experience, and Training

4.3. Investigating Demographic and Professional Differences

4.4. Barriers to Effective Care Beyond Individual Readiness

4.5. Future Directions: A Multi-Level Approach for the Greek Context

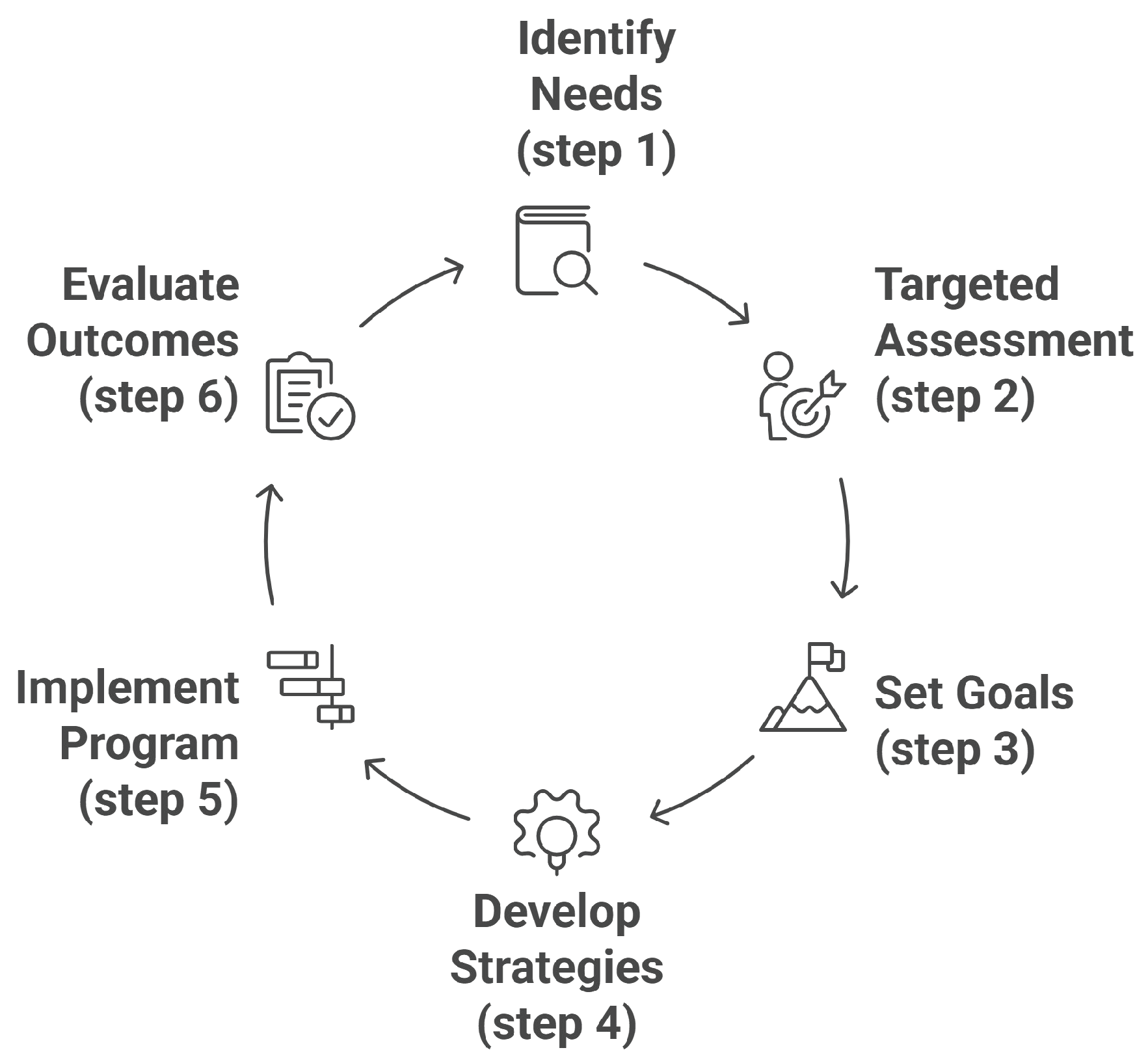

4.6. A Structured Framework for Training: Applying Kern’s Six-Step Model

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BI | Brief Intervention |

| CPD | Continuing Professional Development |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HR | Health Region |

| LHT | Local Health Team/Unit |

| M | Mean |

| Max | Maximum |

| MI | Motivational Interviewing |

| Min | Minimum |

| N | Number (Sample size/cases) |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| SBIRT | Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Casey, B.J.; Jones, R.M.; Hare, T.A. The adolescent brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, L.P. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000, 24, 417–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, B.; Good, J.; Singh, G.; Deyo, M.; Marshall, R.; Oesterle, T. Adolescent substance use disorder in primary care: Challenges in screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241276817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2023. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2023.html (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the Future Survey 2024: Overview of Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/2024/12/reported-use-of-most-drugs-among-adolescents-remained-low-in-2024 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Rotarou, E.S.; Sakellariou, D. Austerity and disabled people in Greece: The impact of a neoliberal response to the debt crisis. Disabil. Soc. 2017, 32, 1059–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Chliaoutakis, J.; Koukouli, S.; Papadakaki, M.; Papadaki, V.; Koutis, A. Exploring barriers to primary care for migrants in Greece in times of austerity: Perspectives of service providers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Fotiou, A.; Kanavou, E.; Stavrou, M.; Kokkevi, A. Substance Use, Alcohol, Smoking and Other Addictive Behaviour in Adolescents: Summary of Key Findings of the Greek Nationwide School Population Survey on Substance Use and Other Addictive Behaviours-ESPAD-Greece 2025; University Mental Health, Neurosciences Precision Medicine Research Institute “COSTAS STEFANIS” (UMHRI): Athens, Greece, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S.J.; Williams, J.F.; Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzouvara, V.; Papadopoulos, C.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A. Systematic review of the prevalence of mental illness stigma within the Greek culture. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2016, 62, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korhonen, J.; Axelin, A.; Stein, D.J.; Seedat, S.; Mwape, L.; Jansen, R.; Groen, G.; Grobler, G.; Jörns-Presentati, A.; Katajisto, J.; et al. Mental health literacy among primary healthcare workers in South Africa and Zambia. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hook, S.; Harris, S.K.; Brooks, T.; Carey, P.; Kossack, R.; Kulig, J.; Knight, J.R. The “Six T’s”: Barriers to screening teens for substance abuse in primary care. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boom, S.M.; Oberink, R.; Zonneveld, A.J.E.; van Dijk, N.; Visser, M.R.M. Implementation of motivational interviewing in the general practice setting: A qualitative study. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Screening for Substance Use in the Pediatric/Adolescent Medicine Setting. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/science-to-medicine/screening-substance-use/in-pediatric-adolescent-medicine-setting (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- O’Brien, D.; Harvey, K.; Howse, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C. Barriers to managing child and adolescent mental health problems: A systematic review of primary care practitioners’ perceptions. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e693–e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristopoulos, I.; Sazakli, E.; Leotsinidis, M. General practitioners’ views towards management of common mental health disorders: The critical role of continuing medical education. BMC Prim. Care 2023, 24, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, H.; Beni, Z.H.M.; Deris, F. Using Kern model to design, implement, and evaluate an infection control program for improving knowledge and performance among undergraduate nursing students: A mixed methods study. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications Office of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679; General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L 119, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Shama, M.E.; Meky, F.A.; Abou El Enein, N.Y.; Mahdy, M.Y. The effect of a training program in communication skills on primary health care physicians’ knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2009, 84, 261–283. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, T.L.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Michie, S. Using theories of behaviour change to inform interventions for addictive behaviours. Addiction 2010, 105, 1879–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, Á.N.D.S.; de Azevedo, K.P.M.; Braga, L.P.; de Medeiros, G.C.B.S.; de Oliveira Segundo, V.H.; Bezerra, I.N.M. Training in communication skills for self-efficacy of health professionals: A systematic review. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.A.; Mansour, K.A.; Wynter, K.; Francis, L.M.; Rogers, A.; Angeles, M.R.; Pennell, M.; Biden, E.; Harrison, T.; Smith, I. Men’s and Boys’ Barriers to Health System Access: A Literature Review; Deakin University, Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development (SEED): Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-07/men-s-and-boys-barriers-to-health-system-access-a-literature-review.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Dielissen, P.W.; Bottema, B.J.; Verdonk, P.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L. Attention to gender in communication skills assessment instruments in medical education: A review. Med. Educ. 2011, 45, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erku, D.A.; Gartner, C.E.; Morphett, K.; Steadman, K.J. Beliefs and self-reported practices of health care professionals regarding electronic nicotine delivery systems: A mixed-methods systematic review and synthesis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orji, R.; Mandryk, R.L.; Vassileva, J. Health Belief Model. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- D’Errico, F.; Cicirelli, P.G.; Papapicco, C.; Scardigno, R. Scare-Away Risks: The effects of a serious game on adolescents’ awareness of health and security risks in an Italian sample. Psych 2022, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, F.; Cicirelli, P.G.; Corbelli, G.; Paciello, M. Rolling minds: A conversational media to promote intergroup contact by countering racial misinformation through socioanalytic processing in adolescence. Psychol. Pop. Media 2024, 14, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannouli, V.; Hyphantis, T. In the labyrinth of e-Health: Exploring attitudes towards e-Health in Greece. J. Psychol. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, H.; Campbell, P.; Maxwell, M.; O’Carroll, R.E.; Dombrowski, S.U.; Williams, B.; Cheyne, H.; Coles, E.; Pollock, A. Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: A systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettema, J.; Steele, J.; Miller, W.R. Motivational interviewing. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 1, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, S.; Paris, M., Jr.; Añez, L.; Nich, C.; Canning-Ball, M.; Hunkele, K.; Olmstead, T.A.; Carroll, K.M. The effectiveness of a competency-based supervision approach for promoting clinicians’ use of motivational interviewing. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2016, 66, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, L.B.; Hamilton, M.A.; Mitchell, E.W.; Kiwanuka-Tondo, J.; Fleming-Milici, F.; Proctor, D. A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. J. Health Commun. 2004, 9, 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.; Foster, R.; Marks, J.; Morshead, R.; Goldsmith, L.; Barlow, S.; Sin, J.; Gillard, S. The effectiveness of one-to-one peer support in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, D.E.; Thomas, P.A.; Hughes, M.T. (Eds.) Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J. Learning needs assessment: Assessing the need. BMJ 2002, 324, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Physicians by Sex and Age. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Physicians_by_sex_and_age (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic/Category | N (%)/Value |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 48 (14.5%) |

| Female | 281 (84.9%) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (0.6%) |

| Age (Years) | |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | 46.76 (8.45) |

| Range (Minimum-Maximum) | 41 (25–66) |

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 101 (30.5%) |

| Physician | 94 (28.4%) |

| Health Visitor | 71 (21.5%) |

| Administrative Staff | 29 (8.8%) |

| Midwife | 22 (6.6%) |

| Social Worker | 9 (2.7%) |

| Other | 5 (1.5%) |

| Years of Experience | |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | 19.28 (9.46) |

| Range (Minimum-Maximum) | 41 (1–42) |

| Work Setting (N = 323) | |

| Health Centers | 253 (78.3%) |

| Local Health Teams | 56 (17.3%) |

| Regional Clinics | 7 (2.2%) |

| Multi-purpose Reg. Clinics | 4 (1.2%) |

| Private EOPYY clinics | 2 (0.6%) |

| Municipal Clinics | 1 (0.3%) |

| Variable/Scale | Mean (M) | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Scale | ||||

| Communication strategies | 2.95 | 1.00 | 1 | 5 |

| Management of addictive behaviors | 2.45 | 0.97 | 1 | 5 |

| Risk factors | 3.01 | 1.00 | 1 | 5 |

| Protective factors | 2.81 | 0.94 | 1 | 5 |

| Screening tools | 2.25 | 0.92 | 1 | 5 |

| Motivational interviewing | 2.25 | 1.05 | 1 | 5 |

| Attitudes/Perceptions | ||||

| Perceived Importance | 4.31 | 1.02 | 1 | 5 |

| Sense of Preparedness | 2.65 | 1.01 | 1 | 5 |

| Expectations from Training | ||||

| Recognition of early signs | 4.43 | 0.73 | 2 | 5 |

| Understanding risk/protective factors | 4.41 | 0.75 | 1 | 5 |

| Application of motivational interviewing | 4.44 | 0.79 | 1 | 5 |

| Development of communication methods | 4.59 | 0.62 | 3 | 5 |

| Variable | Coefficient () | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge_Mean | 0.918 | 0.829–1.006 | <0.001 |

| Importance | 0.063 | −0.017–0.143 | 0.120 |

| Age | −0.003 | −0.010–0.005 | 0.516 |

| Experience | 0.000 | −0.006–0.006 | 0.960 |

| Gender_Male | −0.178 | −0.407–0.051 | 0.127 |

| WorkSetting_Local Health Team | −0.161 | −0.410–0.088 | 0.205 |

| WorkSetting_Other | 0.013 | −0.176–0.202 | 0.891 |

| Profession_Physician | 0.004 | −0.352–0.360 | 0.984 |

| Profession_Midwife | −0.014 | −0.511–0.483 | 0.956 |

| Profession_Health Visitor | −0.074 | −0.430–0.283 | 0.686 |

| Profession_Social Worker | 0.301 | −0.091–0.693 | 0.131 |

| Profession_Other | −0.103 | −0.601–0.396 | 0.687 |

| Barrier | N Selecting “Yes” | % Selecting “Yes” |

|---|---|---|

| a. Lack of training and knowledge | 290 | 87.6% |

| b. Services are not designed with adolescents in mind | 250 | 75.5% |

| c. Ignorance about where cases can be referred | 183 | 55.3% |

| d. Reduced parental support | 151 | 45.6% |

| e. Low internal motivation of adolescents | 145 | 43.8% |

| f. Time constraints in interactions | 142 | 42.9% |

| g. Reduced effectiveness of screening tools | 90 | 27.2% |

| Dependent Variable | Grouping: Gender Z (p-Value) | Grouping: Profession (df = 5) (p-Value) | Grouping: Work Setting (df = 5) (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||

| Communication strategies | −2.418 (0.016) * | 22.609 (<0.001) ** | 6.886 (0.229) |

| Management of addictive behaviors | −1.853 (0.064) | 18.309 (0.003) ** | 5.178 (0.395) |

| Risk factors | −0.471 (0.638) | 12.869 (0.025) * | 6.015 (0.305) |

| Protective factors | −0.895 (0.371) | 17.529 (0.004) ** | 3.868 (0.569) |

| Screening tools | −0.853 (0.393) | 10.467 (0.063) | 0.967 (0.965) |

| Motivational interviewing | −0.089 (0.929) | 21.229 (0.001) ** | 5.335 (0.376) |

| Attitudes/Perceptions | |||

| Perceived Importance | −2.031 (0.042) * | 5.360 (0.374) | 6.414 (0.268) |

| Sense of Preparedness | −1.990 (0.047) * | 11.314 (0.045) * | 5.392 (0.370) |

| Expectations from Training | |||

| Recognition of signs | −2.504 (0.012) * | 4.482 (0.482) | 5.734 (0.333) |

| Application of MI | −2.681 (0.007) ** | 8.517 (0.130) | 8.336 (0.139) |

| Development of communication | −2.302 (0.021) * | 10.150 (0.071) | 4.898 (0.428) |

| Understanding factors | −2.069 (0.039) * | 3.795 (0.579) | 3.587 (0.610) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meditskos, A.; Hatzipantelis, E.; Bacopoulou, F.; Kaltsa, M.; Stachteas, P.; Smyrnakis, E. Investigation of Educational Needs of Primary Health Care Professionals in Greece for the Management of Adolescent Addictive Behaviors. Adolescents 2025, 5, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030049

Meditskos A, Hatzipantelis E, Bacopoulou F, Kaltsa M, Stachteas P, Smyrnakis E. Investigation of Educational Needs of Primary Health Care Professionals in Greece for the Management of Adolescent Addictive Behaviors. Adolescents. 2025; 5(3):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030049

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeditskos, Andreas, Emmanouel Hatzipantelis, Flora Bacopoulou, Maria Kaltsa, Panagiotis Stachteas, and Emmanouil Smyrnakis. 2025. "Investigation of Educational Needs of Primary Health Care Professionals in Greece for the Management of Adolescent Addictive Behaviors" Adolescents 5, no. 3: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030049

APA StyleMeditskos, A., Hatzipantelis, E., Bacopoulou, F., Kaltsa, M., Stachteas, P., & Smyrnakis, E. (2025). Investigation of Educational Needs of Primary Health Care Professionals in Greece for the Management of Adolescent Addictive Behaviors. Adolescents, 5(3), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030049