Abstract

Underserved communities in South Africa face persistent inequalities that hinder the health and well-being of young people, particularly during the critical developmental phase of adolescence. This study explored perceptions of adolescent health and well-being among parents/guardians and community leaders of adolescent girls in two underserved communities in Gauteng, focusing on food insecurity, alcohol use, and transactional sex. The sample comprised 63 participants, including parents/guardians of adolescents and community leaders (such as individuals working for community-based organisations or regarded as trusted figures in the community). Two facilitators conducted 11 focus group discussions in English, Sepedi, and isiZulu. All sessions were audio-recorded, translated, and transcribed. The transcripts were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. The findings reflect community and parental narratives of risk, showing how adolescents in Mamelodi and Soshanguve—two underserved communities in Gauteng—experience food insecurity that contributes to underage drinking and transactional sex, ultimately leading to teenage pregnancies and HIV infection. The results highlight the risks faced by adolescents, showing how social and structural factors create conditions that enable underage drinking and transactional sex, thereby increasing vulnerability to pregnancy and HIV infection. This study highlights the urgent need for interventions that can effectively address these narratives of risk.

1. Introduction

Adolescents comprise nearly 2 billion individuals worldwide [1]. In low- and middle-income countries, they represent 25.2% of the population, with Africa projected to have the largest adolescent cohort by 2100 [1]. South Africa’s total population is estimated at 63.02 million [2], of whom 18.5% are adolescents [3]—amounting to nearly 10 million young people [4]. This demographic profile highlights South Africa’s relatively youthful population, a figure expected to increase rapidly through to 2050 [3]. Against this backdrop, there is a growing need to improve adolescent health and well-being [1]. Achieving this, however, requires interventions that are responsive to the contextual and lived realities of adolescents. The health behaviours formed during this stage of development have a lasting impact on health and well-being [5], leading to either enhanced or reduced health outcomes.

Adolescents in South Africa face unique challenges shaped by the heterogeneity of their lived experiences. A snapshot of this diversity is reflected in demographic data, which show that the majority of South Africans identify as black African, followed by coloured (a term used in South Africa to denote mixed-race), white, and then Indian/Asian [5,6]. Population group continues to be a strong indicator of poverty risk, with the annual median household expenditure of white South Africans more than ten times higher than that of black Africans [7]. The high rates of poverty experienced are closely linked to adverse impacts on nutrition, education, health, housing, and access to information for adolescents in South Africa [6]. Some of these challenges include varying degrees of poverty, inequality, discrimination, safety concerns, family home environments, educational disparities, and environmental, cultural, and linguistic diversity. Together, these experiences make adolescence a uniquely shaped developmental period for each young person in South Africa. Many of these exposures place significant strain on adolescent health and well-being, particularly in underserved communities. Such communities are characterised by high levels of poverty and unemployment, combined with limited access to basic services and socio-economic infrastructure, often leading to an overreliance on social grants. They are frequently spatially polarised, clearly divided from wealthier communities, and commonly situated on the peripheries of cities with restricted access to services and economic hubs [8]. It is also important to recognise that South African communities have long and complex historical backgrounds, which makes each community distinctive in terms of its economic profile [9].

Adolescents in underserved communities often encounter significant barriers to improving their health and well-being. In South Africa, such communities are characterised by socio-economic constraints—poverty, geographic isolation, language barriers, and broader social determinants—that restrict access to essential resources and opportunities. These limitations are closely linked to diminished economic prospects, poor-quality education, and inadequate healthcare, all of which undermine the overall well-being of the community. Many of these barriers arise from immediate socio-economic conditions, while others stem from emerging determinants of adolescent health. These determinants include substance use and risky behaviours, exposure to violence and inequality, economic insecurity, trauma and mental health challenges, as well as environmental stressors.

South African adolescents have distinctive experiences, as outlined above, which further shape their health needs. The leading risk factors for morbidity and mortality among adolescents include substance use, teenage pregnancy, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [3]. These risks are closely influenced by food insecurity, itself often rooted in poverty and limited economic opportunities.

Poverty has been strongly associated with hunger and poor nutrition [10]. Households that experience these conditions are defined as food insecure. In such households, children, adolescents, and adults frequently depend on cheap, unhealthy food alternatives, or they are forced to adjust their food intake by reducing portions, skipping meals, or going hungry [11], often as a result of limited resources. In South Africa, nearly 63.5% of households are classified as food insecure [12]. A review of the impacts of food insecurity on adolescent health and well-being indicates that it is often associated with smoking, alcohol consumption, poor sleep, and other adverse health outcomes [11]. Clear associations have also been found between food insecurity and substance use among adolescents [13,14]. One study among young South Africans covertly suggested that the provision of alcohol in contexts of food insecurity was linked to expectations of sex [15], a finding supported by a broader body of evidence [16,17]. Food insecurity has also been associated with other behaviours that compromise adolescent health and well-being [11,18,19,20]. These include negative impacts on sexual and reproductive health, where it has been significantly linked to age-disparate sex among adolescents in South Africa [21] and to increased odds of transactional sex [22].

A study conducted in South Africa among adolescents and young adults found that 45% reported substance use in the past twelve months [23]. Among those currently using substances, alcohol was the most common (74%), followed by tobacco (12%) and cannabis (11%) [23]. Adolescents from underserved communities in South Africa reported that 48% had consumed alcohol, with increased likelihood of current alcohol use among this group [24]. Substance use during adolescence has significant consequences for the health and well-being of young people in adulthood [25], predisposing them to substance use disorders later in life [26], as well as other health complications. Access to alcohol for adolescents is frequently facilitated by older individuals or by obtaining it in local settings. It has been reported that, within these contexts, adolescent girls who accept alcohol are often viewed as engaging in a form of currency for sexual exchange [27]. There is a prevailing notion that accepting alcohol is equivalent to consenting to sex [27].

The example of adolescent girls accepting alcohol, which is often regarded as a form of consent for sex, illustrates how sexual exchange can be transactional. Transactional sex has been interpreted in various ways within the social sciences, but a review by Stoebenau and colleagues [28] provides a useful framework for understanding this concept. They propose that transactional sex can be categorised into three paradigms: (i) sex for basic needs, (ii) sex for improved social status, or (iii) sex as a material expression of love [28]. There is evidence that adolescent girls frequently engage in transactional sex involving alcohol, which impairs judgement and decision-making [29,30].

Engagement in transactional sex often falls into one of three paradigms. Data show that adolescent girls may engage in such relationships with older men: (i) to meet basic needs arising from poverty, hunger, or resource scarcity [17,31]; (ii) to enhance their social status by gaining prestige and approval [17,31]; or (iii) to obtain luxury items and material possessions, which are often framed as symbols of love. Regardless of the paradigm that may be driving adolescent girls’ involvement in transactional sex in underserved communities, transactional sex and age-disparate relationships are associated with increased HIV risk [32]. These age-disparate relationships have been reported to involve age differences of five years or more [33], and sometimes 10 years or more, typically involving older men with financial resources [31]. Adolescent girls often have limited agency and negotiation power, which leads to higher rates of sexually transmitted infections, HIV, and teenage pregnancy.

In seeking to understand and respond to the unique experiences and exposures of adolescent girls in underserved communities, it is essential to incorporate the perspectives of parents/guardians and community leaders who engage with adolescents, alongside prioritising adolescent voices. Parents/guardians and community leaders offer valuable insights into the socio-economic and cultural factors that influence decisions affecting health and well-being.

When examining perceptions of adolescent health and well-being in underserved communities, several common concerns emerge. These include food insecurity, substance use, early sexual debut, transactional sex, teenage pregnancy, and HIV acquisition. Among these, food insecurity often stands out as a key driver shaping health and well-being. While the relationship between food insecurity and transactional sex has been studied extensively, little is known about how this dynamic specifically affects adolescents [34]. Transactional sex can be defined as a sexual relationship in which sex is exchanged for material benefits such as money, gifts, or services. While concerns related to adolescent health and well-being in underserved communities—such as substance use, early sexual debut, teenage pregnancy, and HIV acquisition—are well recognised, it remains unclear how these factors shape the perceived relationship between food insecurity and transactional sex among adolescents in South Africa. This study therefore qualitatively explored how parents, guardians, and community leaders perceive the factors influencing the health and well-being of adolescent girls in two underserved communities in Gauteng, with particular attention to food insecurity, alcohol use, and transactional sex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed an exploratory qualitative design, epistemologically aimed at examining perceptions of the factors shaping health and well-being among parents, guardians, and community leaders of adolescent girls in two underserved communities—Mamelodi and Soshanguve in Gauteng, South Africa—with a focus on food insecurity, alcohol use, and transactional sex. An interpretivist ontological lens was applied to explore the socially constructed realities of these parents/guardians and community leaders. This study is presented using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) [35].

2.2. Recruitment and Participants

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling, focusing on parents or guardians of adolescents and community leaders working with adolescents in two communities in Gauteng province, South Africa. For the purposes of this study, community leaders were defined as individuals holding positions of influence or responsibility within these communities. This group comprised both formal leaders, such as those involved with local organisations, faith communities, and schools, as well as informal leaders, recognised as trusted figures among community members. The two communities were purposively selected as they are among the largest townships in Gauteng province.

The province was chosen as it forms part of a broader study aimed at developing an intervention for adolescents in these areas to address their health concerns. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling and were required to meet one of the following criteria: (i) be a parent or guardian of an adolescent in one of the two communities, or (ii) be a community leader in one of the two communities involved in adolescent-related programmes.

The final sample included 63 participants across 11 focus group discussions (see Table 1), including parents/guardians (n = 39), community leaders (n = 9), and individuals who were both parents/guardians and community leaders (n = 15). Participants ranged in age from 19 to 58 years, with more female participants (n = 50). Most had completed high school as their highest level of education (n = 37), and more than half were unemployed (n = 37). Among community leaders, most had between one and three years of experience in their role (n = 10). For parents/guardians, the majority of households included either 1 (n = 30) or 2 (n = 17) adolescents (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 63).

2.3. Procedures

This study received ethical approval from the University of Pretoria Research Ethics Committee (Reference: HUM056/0624). Following approval, parents/guardians and community leaders were approached, informed about the study, and invited to participate. Those who consented were assigned to one of the 11 focus group discussions held across the two underserved communities in Gauteng. Only the researcher’s contact details were shared with participants, and no prior relationships had been established before the study.

2.4. Data Generation

Focus group discussions were facilitated by two researchers. The first researcher conducted all discussions held in English, while the second led those in which participants used a mix of Sepedi, isiZulu, and English, with the first researcher providing oversight. The first researcher was a male with an academic background in psychology and public health, holding a doctoral degree. At the time of the study, he was an associate professor with extensive expertise in adolescent and emerging adult health. The second researcher was a male with a background in community youth work and was enrolled as an undergraduate social science student. He worked as an independent researcher and community youth worker, bringing considerable experience in youth development in South Africa.

All focus group discussions were audio-recorded and lasted between one hour and one hour and thirty minutes. Each session began with a free-listing activity, informed by the work of Colucci [36] and Bernard [37], to explore perceptions of adolescent health and well-being among caregivers and community leaders in the two communities. The discussions were guided by both the free-listing activity and a semi-structured discussion guide.

Separate focus groups were held for parents/guardians and community leaders. The researchers promoted turn-taking and fostered a safe, inclusive environment to minimise potential power dynamics among participants. Following each session, the researchers debriefed, reflected on the process, and reviewed their emerging thoughts and notes. No additional or repeat interviews were conducted with participants.

2.5. Data Analysis

All focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim by an independent transcriber. Discussions conducted in a mixture of Sepedi, isiZulu, and English were translated into English. The first researcher reviewed all translated and transcribed material to ensure accuracy. The transcripts were analysed using manual coding through a flexible and organic process that embraced ‘reflexivity, subjectivity, and creativity’ [38], guided by Braun and Clarke’s [39] reflexive thematic analysis process. This process can be summarised in six steps, namely (i) becoming familiar with the data, (ii) generating initial codes from the data, (iii) establishing themes, (iv) reviewing and revising the potential themes, (v) defining and naming the themes, and ending with (vi) disseminating the findings through a report.

Furthermore, the data analysis process was informed by investigator triangulation, whereby data were collected by more than one researcher, and by data source triangulation, which combined insights from the free-listing activity with those from the focus group discussions to identify health behaviours. In line with Braun and Clarke’s [40] reflexive thematic analysis, data adequacy was not conceptualised through the notion of ‘saturation’, which assumes that themes emerge until no new insights are identified. Instead, adequacy was understood in terms of the dataset providing sufficient richness and variation across participant conversations to meaningfully address the study’s aims.

2.6. Rigour

In this study, trustworthiness, dependability, and confirmability were supported through rich descriptions and transparency across all stages, including recruitment, data generation, and analysis [41]. These principles were further reinforced by providing clear justification for how the chosen methods of recruitment, data generation, and analysis were best suited to the study’s aims [42]. In addition, the researchers involved in data collection met to discuss and reflect on the discussions, processes, emerging insights, and debriefing notes, thereby fostering reflexivity throughout the study [41,42].

3. Results

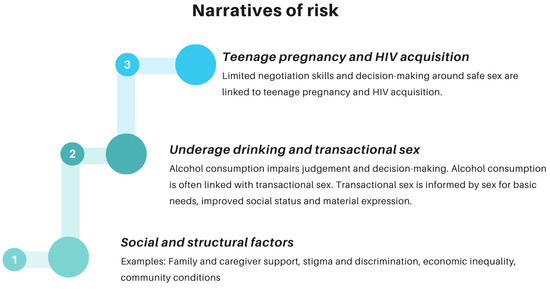

The results highlight narratives of risk for adolescents, showing how social and structural factors create conditions for underage drinking and transactional sex (Theme 1), which in turn heighten vulnerability to pregnancy and HIV acquisition (Theme 2; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A diagrammatic outline of the themes representing the narratives of risk for adolescents, where social and structural factors pave the way for underage drinking and transactional sex, leading to teenage pregnancy and HIV acquisition.

3.1. Theme 1: Social and Structural Factors Paving the Way for Underage Drinking and Transactional Sex

The stories shared by the community and parents/guardians of adolescents reveal how food insecurity and limited access to financial resources frequently lead adolescent girls to form relationships with older men and engage in transactional sex. The older men mentioned are typically at least ten years older than the adolescent girls and possess greater financial means. These individuals may include men aged 30 and above. The first sub-theme illustrates how social and structural factors, particularly those associated with restricted financial resources, facilitate relationships with older men and transactional sex.

3.1.1. Sub-Theme 1.1: Limited Financial Resources Paving the Way for Relationships with Older Men and Transactional Sex

The first sub-theme presents evidence of concerns expressed by the community and parents/guardians regarding adolescent girls who often visit taverns and local alcohol outlets, as these venues are frequented by older men with greater financial means. The following accounts from two parents/guardians illustrate how adolescent girls form relationships with older men, frequently attracted by their access to cars and their ability to provide material goods that the girls’ families cannot afford.

“I will talk about girls specifically when it comes to dress codes, smoking, going out to have a nice time or [at] taverns … the thing is they start when they go to these taverns and one finds themselves with a man who owns a car”(Participant 2_129, Parent/guardian, Age 34, Female).

“I think that money does play a role in the well-being of our young people. I think having little money affects them. These days, there are malls in our areas …when they [referring to adolescent girls] go to the mall, they meet older guys who buy them things that they cannot afford or that they cannot get from home. These guys will buy them streetwise [referring to a meal at a popular takeout restaurant] and other nice things, and kids end up getting into these relationships with these older guys so that they can get the things they buy for them, but unfortunately, they also give them diseases”(Participant 4_169, Parent/guardian, Age 44, Female).

Another parent/guardian recounted an encounter with an adolescent girl who is a neighbour, explaining that the girl regularly engaged in transactional sex with an older man in order to provide food for herself and her family. The parent/guardian continued:

“She’s still young [referring to the adolescent girl who is her neighbour]. She still go[es] to school ... she’s doing her grade 11 this year … She has a child … But she’s not staying with her mother. She found her own place … during the night, there were noises outside, and it was like a physical fight … So, in the morning, I called her and said: Why were you fighting during the night? … And she said: No, I was not in the mood for him [referring to the older man]. And I said: Is he your boyfriend? And she said: No, he’s not my boyfriend. I only go to him when we don’t have food in the house because I have to help my mother … And I was like: If this child can sleep with that man, for a bag of mealie meal [maize meal], what’s going on the whole year? The whole month? If the mother cannot provide, that means she’s going to sleep with that man every day for food. She has to go to school also”(Participant 2_134, Parent/guardian, Age 38, Female).

One community leader working with adolescents described how he frequently observed the pathway of risk for adolescent girls who often lacked food at home or were deprived of basic resources due to financial hardship:

“… girls go to the tavern offering older men to buy them clothes and then afterwards they will sleep with them and then they will not [think about] the consequences … in the township that I live both here in Mamelodi and Soshanguve I have also noticed that everyone just do[es] that …”(Participant 1_099, Community Leader, Age 25, Male).

The first two reflections above describe how adolescent girls in Mamelodi and Soshanguve frequently reside in households with limited financial resources, resulting in restricted access to clothing and food. Consequently, some choose to form relationships with older men to obtain clothes, food, and transportation. Within these relationships, adolescent girls are often provided with material goods in exchange for sexual activity. This transactional dynamic is shaped by economic deprivation, as older men exploit the lack of resources to secure sexual relationships, offering material benefits such as clothing, food, and mobility in return.

The third quote recounts the experience of an adolescent girl who has a child with an older man and participates in transactional sex to secure food for herself and her family. Social and structural factors associated with limited financial resources contribute to the prevalence of transactional sex. Experiencing financial hardship in meeting fundamental needs, such as food and clothing, frequently compels adolescent girls to form relationships with older men. These men often supply alcohol to the girls, which initiates a sequence of risk, subsequently leading to unprotected, transactional sex, as discussed in the following sub-theme.

3.1.2. Sub-Theme 1.2: The Combination of Alcohol and Transactional Sex at Taverns, Fuelled by Limited Access to Resources

Some community leaders working with adolescents in the two communities noted that underage girls are often able to purchase alcohol, which grants them access to taverns and the older men who frequent them. Interaction with these men frequently leads to alcohol use and transactional sex, a pattern linked to the inability of parents to provide basic resources due to financial hardship:

“… and the alcohol issue, the taverns now they [referring to taverns] sell alcohol to the young people. They are no longer as strict as before. Any young person can go into any tavern and purchase alcohol, whether wearing [their] school uniform or not … If you go to any place to purchase alcohol, you’ll find young girls there dressed indecently. And when you look at their age, you can tell that this person is very young. But they are there, and they are sitting among older men. So what are they doing there? Obviously [they are] not just drinking; they [are] probably getting sponsored [referring to being offered money, food and drinks] by these older men. And yes, they do sleep with them. So it’s like every night there’s always that young girl who’s dressed indecently going to a tavern … I just want to add on this issue. I think the government has failed our parents because now, if our parents are not earning that well, they can’t provide for these young girls. And if the government is failing the parents, they’re failing the kids as well”(Participant 2_069, Community Leader, Age 33, Female).

“… well I know that these underage children, these teenagers drink a lot of alcohol and they sleep with older men … these men buy them alcohol then sleep with them”(Participant 1_413, Community Leader, Age 49, Female).

A parent/guardian reflected on her daily experiences within the community, echoing the concerns expressed by the community leaders. She explained the following:

“… now if you go stand next to a tavern and you drive a big car, you will see that they [referring to adolescent girls] will start chasing you, all of them … and the owners at the tavern also sell alcohol to underage children”(Participant 4_412, Parent/guardian, Age 42, Female).

The lack of financial resources was a recurring theme in discussions with both community members and parents/guardians of adolescents. This scarcity often led adolescent girls to spend time with older men at taverns, particularly when those men displayed symbols of wealth, such as driving luxury cars. In these settings, adolescent girls engaged in underage drinking, gaining access to taverns in Mamelodi and Soshanguve without restriction despite their age. Alcohol was frequently provided by older, affluent men who used it as a means to lure girls into transactional sexual relationships, often fulfilling immediate needs for food, clothing, and transportation, as highlighted in sub-theme 1.1 above.

3.2. Theme 2: Increasing Risk of Teenage Pregnancy and HIV Acquisition

The unfolding of risk for adolescent girls often means that social and structural factors, driven by a lack of financial resources, lead them to engage in underage drinking and transactional sex with older men. This unfolding of risk results in an increase in teenage pregnancies and HIV acquisition among adolescent girls, as explored in this theme:

“And the alcohol, the young people at Mamelodi always drink on Friday or Saturday, or Sunday, they drink. [For a] nice time [it] is better going to the tavern or groove [referring to a party] or whatever. They [referring to the adolescent] use all the time at the taverns, drinking alcohol and smoking hubbly. This also causes teenage pregnancy. When they are at the taverns or parks, they start things [referring to having sex], and sometimes they don’t use a condom, and these are children. It’s like 14 years, 12 to 14 upwards. They didn’t go to the clinic to get prevention”(Participant 3_041, Parent/guardian, Age 56, Female).

“I can say 50% of the girls in Mamelodi. They find themselves HIV-positive without knowing where they got it. But if you ask: I was drunk and I slept with someone, I didn’t use a condom. You see, it’s affecting their health a lot. If you can ask a 15-year-old, why are you pregnant when you’re 15? I was at the tavern. I went home with this man, or I slept with two men during that time at the tavern. I don’t know who the father is. Did you test? [referring to an HIV test] Yes. What’s the result? I’m positive [referring to testing HIV-positive]”(Participant 2_410, Parent/guardian, Age 38, Female).

“… the health of the young people they are not in good shape these days. For instance, they date older men. They give them the virus, and then if the girls, go to the clinic to be tested, they find that they are HIV positive. Some do take the pills [referring to antiretroviral therapy]. When they go home to show their partners, they’ll be beaten. Telling them why they are saying that they want to give them the virus, while they know they go to school and they have other boyfriends there. Some, they will tell them: Baby, let’s go and test. So that you can even get the pills. Some will not allow that [referring to getting tested and receiving treatment]. They will want to share the same pills that the girl child got at the clinic”(Participant 1_041, Parent/guardian, Age 37, Female).

Excerpts from conversations with community leaders and parents/guardians illustrate how underage drinking is tolerated by local tavern owners, which often enables adolescent girls to gain access to these establishments. There, they meet older men who provide them with alcohol, leading to intoxication and engagement in underage, transactional sex. Frequently, this occurs without any protection, resulting in unintended teenage pregnancies and HIV infections. The data also reveal how older men would either beat the adolescent girls upon learning that they are HIV-positive, threatening to have other partners at school as well. Alternatively, there are instances where the older men seek to exploit the adolescent girls’ antiretroviral therapy, avoiding the need for testing and treatment themselves. This phenomenon is often referred to as informal antiretroviral therapy use.

4. Discussion

Bhekisisa, the Centre for Health Journalism, reports that one in seven mothers in South Africa are adolescents [43]. They further note that nearly 365 adolescent girls give birth each day in the country, with approximately 10 of these births occurring among girls younger than 15 [43]. The prevalence of adolescent births is disproportionately higher in underserved communities. When exploring the perceptions of adolescent health and well-being among parents/guardians and community leaders in Mamelodi and Soshanguve—two underserved communities in Gauteng—concerns around food insecurity and its links to transactional sex and teenage pregnancy were consistently raised. The findings illustrate how food insecurity operates as a central driver within the unfolding of risks. As reflected in the narratives, social and structural factors such as food insecurity create pathways into underage drinking and transactional sex, which in turn heighten the risk of teenage pregnancy and HIV acquisition among adolescent girls in these two communities.

The social and structural factors shaping the lives of adolescent girls are closely tied to the broader contextual landscape of underserved communities in South Africa and beyond, where poverty and food insecurity are pervasive [17]. In South Africa, as in many other developing contexts, more than 15 million people experience food insecurity on a daily basis [44]. This equates to approximately 63.5% of households being food insecure, indicating that a significant proportion of adolescents are directly affected by inadequate access to food.

Adolescents experiencing food insecurity are often more focused on meeting their immediate basic needs than on concerns about the future [45]. Among female adolescents, this frequently manifests in engaging in transactional sex with men in exchange for food, reflecting both reliance on and provision of basic sustenance [21,45]. The findings of the current study echo this pattern, showing how social and structural factors in the two underserved communities perpetuate food insecurity and, in turn, contribute to adolescent girls engaging in underage drinking and transactional sex with older men.

A large-scale global study conducted across 53 countries found that among the 16% of adolescents who had ever engaged in sex, more than half (51%) experienced food insecurity. Female adolescents were particularly likely to engage in transactional sex as a means of meeting basic food needs [45]. Male sexual partners frequently withheld or controlled access to food and financial resources as leverage for sexual exchange. Although the global study did not conceptualise transactional sex within a framework of unfolding risk, the current study highlights how this dynamic operates locally. Female adolescents in Mamelodi and Soshanguve often accessed taverns where they encountered men displaying signs of wealth—such as driving luxury cars—who would provide them with alcohol, a pathway that frequently led to transactional sex.

Another study [46] highlighted how food insecurity and transactional sex for food were also associated with other health outcomes, including substance use. The findings of the current study echo these concerns but further indicate that, at times, transactional sex is linked to the pursuit of luxury and prestige. Narratives revealed how adolescents engaged in transactional sex to gain access to parties, clothing, and other material goods, reflecting the paradigms of transactional sex outlined by Stoebenau et al. [28]. These include the paradigms of (i) sex for improved social status and (ii) sex as a material expression of love. It may be assumed that once basic needs such as food are met, higher-level concerns emerge, including the pursuit of luxury items that parents are often unable to provide. Similar findings have been reported in South Africa, where transactional sex has at times been associated with the acquisition of goods linked to luxury and prestige [17].

4.1. Community Environments Shaping Transactional Sex and Alcohol

To further understand the links between food insecurity and transactional sex, it is important to consider the role of communities. Communities often shape perceptions of transactional sex [47]. In contexts where having multiple sexual partners is associated with socially constructed views of masculinity, this has been linked to riskier forms of transactional sex [48]. However, communities with established hubs that facilitate transactional sex tend to show higher prevalence. The findings of this study highlight how taverns function as such hubs, where adolescent girls seek to meet their basic needs through transactional sex, while simultaneously being exposed to underage alcohol consumption.

Taverns provide adolescent girls with access to older men, who frequently purchase alcohol for them. Alcohol has been documented as a form of currency within transactional sex among adults [27]. Among adolescents, however, its availability in taverns creates environments that not only promote underage drinking but also lower inhibitions and heighten vulnerability. Easy access to alcohol at local outlets predisposes adolescent girls to unsafe sexual encounters and transactional sex [49]. Research in communities comparable to those in the present study indicates that there are approximately 10.7 alcohol outlets or taverns per square kilometre [49]. The high density and accessibility of taverns in these areas highlight how easily adolescent girls are able to access such spaces, which often serve as hubs for risky behaviours.

The data from the current study also indicate that adolescents frequently access these taverns, even when underage or wearing school uniform, implying that local policies and regulations concerning underage drinking are often disregarded. Previous reports have found that many adolescents begin consuming alcohol before the age of 13, despite the South African National Liquor Act prohibiting the sale of alcohol to individuals under 18 [24,50]. These findings reinforce the view that community environments contribute to the initiation, continuation, and normalisation of perceptions and behaviours that jeopardise adolescents’ health and well-being.

In the narratives regarding risk for adolescent girls, underage alcohol consumption coupled with transactional sex serves as a pathway to increased teenage pregnancy and HIV acquisition.

4.2. Increased Pathways to Teenage Pregnancy and HIV Acquisition

Norris et al. [51] found that alcohol use and engagement in transactional sex elevate the risk of sexually transmitted infection. Transactional sex is associated with increased HIV acquisition among females in sub-Saharan Africa [52]. Underage alcohol consumption frequently results in adolescent girls making decisions with impaired judgement. Alcohol use has also been shown to affect condom negotiation and related decision-making processes [53]. When adolescent girls consume alcohol and are unable to negotiate condom use during transactional sex, they are placed at increased risk of teenage pregnancy and HIV acquisition. The data in the current study illustrate how adolescent girls are often offered alcohol when visiting taverns, prior to engaging in sex with older men, which impairs their judgement and inhibits their ability to negotiate condom use. This impaired negotiation frequently leads to pregnancy or HIV infection among adolescent girls, as described by parents and guardians in the study. The experiences reported here are consistent with findings from a population-based study across 59 countries, which identified a link between adolescent alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviours [54]. The data also raised concerns about the informal use of antiretroviral treatment among older men, either when they attempted to share medication with adolescent girls they had infected with HIV, or in situations where domestic violence occurred after adolescent girls confronted them upon testing positive for HIV.

This study has several limitations worth noting. It focused exclusively on two underserved communities; although it offers detailed insights into the concerns of parents/guardians of adolescents and community leaders working with young people in these areas, including additional communities would have broadened the range of perspectives. Only the views of parents/guardians and community leaders are explored in this paper, which forms part of a larger study. The experiences of adolescents themselves are being addressed in a separate publication currently in preparation. When using focus group discussions, there is a risk of social desirability bias, as participants may tailor their responses to align with perceived group expectations.

The findings illustrate the narratives of risk faced by adolescent girls in underserved communities, where social and structural factors—including food insecurity and community dynamics—create conditions conducive to underage drinking and transactional sex. These circumstances frequently contribute to a heightened risk of pregnancy and HIV acquisition.

4.3. Implications for Society, Policy, Practice, and Research

The results have important implications for society, policy, practice, and research. Society: Transactional sex is more common than sex work, and therefore interventions within communities must be tailored to the specific context, particularly in underserved and marginalised areas, to disrupt the cycle associated with increased risk. Food insecurity, which is connected to poor mental health outcomes, can also be tackled through school-based or community-based initiatives. These approaches, such as food gardens or meal services, can help alleviate food insecurity and its effects on mental health and well-being.

In addition, access to taverns and local alcohol providers in communities not only leads to increased substance use and abuse at an early age, but is also associated with greater vulnerability to teenage pregnancy and HIV acquisition. Some considerations at the societal level could include verifying the age of patrons upon entry and making condoms available in bathrooms.

Policy: Sexual and reproductive health policies for adolescent girls and young women are insufficient to address emerging risks and must take into account the context in which they are implemented. Paying attention to contextual factors is particularly crucial in underserved communities, where underage and transactional sex undermines the well-being of adolescent girls and young women.

More importantly, the effective enforcement and implementation of the Sexual Offences Act [55] in South Africa requires all community stakeholders to assume responsibility, as it is unlawful for anyone to engage in sexual activity with children and adolescents under the age of 17. There is also a pressing need for strategies to tackle underage drinking in alcohol hubs, such as taverns, particularly within underserved communities [50]. Implementing these policies necessitates a comprehensive community-based approach to overcome the persistent issues associated with the inadequate enforcement of the National Liquor Act [56], which prohibits both access to and the sale of alcohol to adolescents.

Practice: Interventions to address the risks faced by adolescent girls, as identified in the current study, require a comprehensive, multipronged approach. This approach should focus on (i) behavioural aspects, such as enhancing health decision-making skills; (ii) economic and structural measures, including the provision of economic opportunities or access to cash transfers to reduce food insecurity and, consequently, the likelihood of transactional sex, underage drinking, pregnancy, and HIV acquisition; and (iii) community-based interventions that challenge cultural norms and community attitudes that contribute to risk among adolescents.

Research: More qualitative research is needed to explore and understand the contexts in which social and structural factors contribute to underage drinking and transactional sex, resulting in an increased risk of underage pregnancy and HIV acquisition [57].

5. Conclusions

The perspectives of parents/guardians of adolescents and community leaders working with adolescents in two underserved communities in Gauteng province, South Africa, offer valuable insights into the narratives of risk faced by adolescent girls. Social and structural factors, including food insecurity, contribute to underage drinking and transactional sex, which in turn elevate the likelihood of pregnancy and HIV acquisition.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Pretoria Research Development Programme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Faculty of Humanities Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pretoria (protocol code: HUM056/0624 and date of approval: June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants (caregivers and community leaders) for sharing their knowledge and insights; without them, this publication would not be possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Baird, S.; Choonara, S.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Banati, P.; Bessant, J.; Biermann, O.; Capon, A.; Claeson, M.; Collins, P.Y.; De Wet-Billings, N.; et al. A call to action: The second Lancet Commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2025, 405, 1945–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Government. Available online: https://www.gcis.gov.za/resources/south-africa-yearbook-202324 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Bhana, A.; Jonas, K.; Ramraj, T.; Goga, A.; Mathews, C. Achieving universal health coverage for adolescents in South Africa: Health sector progress and imperatives. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2019, 1, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=1854&PPN=Report-03-19-09&SCH=74242 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Spring, B.; Moller, A.C.; Coons, M.J. Multiple health behaviours: Overview and implications. J. Public Health 2012, 34 (Suppl. S1), i3–i10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Available online: https://www.unicef.org/southafrica/media/10731/file/ZAF-UNICEF-situation-analysis-children-adolescents-SA-2024-summary.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-19/Report-03-10-192017.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Hamann, C.; Horn, A.C. Socio-economic inequality in the City of Tshwane, South Africa: A multivariable spatial analysis at the neighborhood level. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 2001–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies. Available online: https://www.tips.org.za/projects/past-projects/inequality-and-economic-inclusion/item/1748-creating-access-to-economic-opportunities-in-small-and-medium-sized-towns (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Van der Berg, S.; Patel, L.; Bridgman, G. Food insecurity in South Africa: Evidence from NIDS-CRAM wave 5. Dev. S. Afr. 2022, 39, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dush, J.L. Adolescent food insecurity: A review of contextual and behavioural factors. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Sciences Research Council. Available online: https://foodsecurity.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/National-Report-compressed.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Tetteh, J.; Ekem-Ferguson, G.; Quarshie, E.N.; Dwomoh, D.; Swaray, S.M.; Otchi, E.; Adomako, I.; Quansah, H.; Yawson, A.E. Food insecurity and its impact on substance use and suicidal behaviours among school-going adolescents in Africa: Evidence from the Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psych. 2024, 33, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Palar, K.; Gooding, H.C.; Garber, A.K.; Tabler, J.L.; Whittle, H.J.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Weiser, S.D. Food insecurity, sexual risk, and substance use in young adults. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.J.; Mannell, J.; Washington, L.; Khaula, S.; Gibbs, A. “Something we can all share”: Exploring the social significance of food insecurity for young people in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Ragnarsson, A.; Mathews, C.; Johnston, L.G.; Ekström, A.M.; Thorson, A.; Chopra, M. “Taking care of business”: Alcohol as currency in transactional sexual relationships among players in Cape Town, South Africa. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duby, Z.; Jonas, K.; McClinton Appollis, T.; Maruping, K.; Vanleeuw, L.; Kuo, C.; Mathews, C. From survival to glamour: Motivations for engaging in transactional sex and relationships among adolescent girls and young women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3238–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasujja, I.; Lund, C.; Salisbury, T.T. Food insecurity and mental health among children and adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2025, 177, 108493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carries, S.; Sigwadhi, L.N.; Moyo, A.; Wagner, C.; Mathews, C.; Govindasamy, D. Associations between household food insecurity and depressive symptomology among adolescent girls and young women during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa. Adolescents 2024, 4, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frongillo, E.A.; Adebiyi, V.O.; Boncyk, M. Meta-review of child and adolescent experiences and consequences of food insecurity. Glob. Food Secur. 2024, 41, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa, R.; Graham, L.; Khan, Z.; Chowa, G.; Patel, L. Food insecurity, sexual risk taking, and sexual victimisation in Ghanaian adolescents and young South African adults. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, T.; Govender, N.; Reddy, P. Food insecurity and risky sexual behaviours among university students in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int. J. Sex Health 2022, 34, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmethi, T.G.; Modjadji, P.; Mathibe, M.; Thovhogi, N.; Sekgala, M.D.; Madiba, T.K.; Ayo-Yusuf, O. Substance use among school-going adolescents and young adults in rural Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmereki, B.; Mathibe, M.; Cele, L.; Modjadji, P. Risk factors for alcohol use among adolescents: The context of township high schools in Tshwane, South Africa. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 969053. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson, R.W.; Heeren, T.; Winter, M.R. Age of alcohol dependence onset: Associations with severity of dependence and seeking treatment. Paediatrics 2006, 11, e755–e763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, T.; Myers, B.J.; Louw, J.; Okwundu, C.I. Brief school-based interventions and behavioural outcomes for substance-using adolescents. Cochrane Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD008969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, M.H.; Aunon, F.M.; Skinner, D.; Sikkema, K.J.; Kalichman, S.C.; Pieterse, D. “Because he has bought for her, he wants to sleep with her”: Alcohol as a currency for sexual exchange in South African drinking venues. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1005–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoebenau, K.; Heise, L.; Wamoyi, J.; Bobrova, N. Revisiting the understanding of “transactional sex” in sub-Saharan Africa: A review and synthesis of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 168, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zembe, Y.Z.; Townsend, L.; Thorson, A.; Ekström, A.M. “Money talks, bullshit walks” interrogating notions of consumption and survival sex among young women engaging in transactional sex in post-apartheid South Africa: A qualitative enquiry. Glob. Health 2013, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, B.; Moultrie, H.; Somji, A.; Chersich, M.F.; Watts, C.; Delany-Moretlwe, S. Alcohol use and sexual risk behaviour among men and women in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Public Health 2017, 17 (Suppl. S3), 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngidi, N.D.; Ntinga, X.; Tshazi, A.; Moletsane, R. Blesser relationships among orphaned adolescent girls in contexts of poverty and gender inequality in South African townships. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucinski, K.B.; Mbita, G.; Atkins, K.; Majani, E.; Komba, A.; Casalini, C.; Drake, M.; Makyao, N.; Galishi, A.; Mlawa, Y.; et al. Transactional sex and age-disparate sexual partnerships among adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania. Front. Rep. Health 2024, 6, 1360339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Beckett, S.; Reddy, T.; Govender, K.; Cawood, C.; Khanyile, D.; Kharsany, A.B. Determining HIV risk for adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) in relationships with “blessers” and age-disparate partners: A cross-sectional survey in four districts in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheira, L.A.; Izudi, J.; Gatare, E.; Packel, L.; Kayitesi, L.; Sayinzoga, F.; Hope, R.; McCoy, S.I. Food insecurity and engagement in transactional sex among female secondary students in Rwanda. AIDS Behav. 2024, 28, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, E. “Focus groups can be fun”: The use of activity-oriented questions in focus group discussions. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport. Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davids, E.L.; Zembe, Y.; de Vries, P.J.; Mathews, C.; Swartz, A. Exploring condom use decision-making among adolescents: The synergistic role of affective and rational processes. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhekisisa. Available online: https://bhekisisa.org/health-news-south-africa/2024-09-13-1-in-7-moms-in-sa-are-teens-we-dive-into-the-numbers/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/15-million-south-africans-dont-get-enough-to-eat-every-day-4-solutions-250700 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Smith, L.; Ward, P.B.; Vancampfort, D.; López-Sánchez, G.F.; Yang, L.; Grabovac, I.; Jacob, L.; Pizzol, D.; Veronese, N.; Shin, J.I.; et al. Food insecurity with hunger and sexual behaviour among adolescents from 53 countries. Int. J. Sex Health 2021, 33, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, H.J.; Sheira, L.A.; Frongillo, E.A.; Palar, K.; Cohen, J.; Merenstein, D.; Wilson, T.E.; Adedimeji, A.; Cohen, M.H.; Adimora, A.A.; et al. Longitudinal associations between food insecurity and substance use in a cohort of women with or at risk for HIV in the United States. Addiction 2019, 114, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latkin, C.A.; German, D.; Vlahov, D.; Galea, S. Neighbourhoods and HIV: A social ecological approach to prevention and care. Am. Psychol. 2013, 68, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.; Winter, A.; Elfstrom, M. Community environments shaping transactional sex among sexually active men in Malawi, Nigeria, and Tanzania. AIDS Care 2013, 25, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letsela, L.; Weiner, R.; Gafos, M.; Fritz, K. Alcohol availability, marketing, and sexual health risk amongst urban and rural youth in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathibe, M.; Cele, L.; Modjadji, P. Alcohol use among high school learners in the peri-urban areas, South Africa: A descriptive study on accessibility, motivations and effects. Children 2022, 9, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, A.H.; Kitali, A.J.; Worby, E. Alcohol and transactional sex: How risky is the mix? Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilburn, K.; Ranganathan, M.; Stoner, M.C.; Hughes, J.P.; MacPhail, C.; Agyei, Y.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Kahn, K.; Pettifor, A. Transactional sex and incident HIV infection in a cohort of young women from rural South Africa. AIDS 2018, 32, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawacki, T.; Vela, T.T.; Harper, S.E.; Jackel, K.M. Causal effects of alcohol consumption on condom negotiation skills of women with varying sexual assault histories. AIDS Behav. 2025, 29, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, C. Associations of tobacco and alcohol use with sexual behaviours among adolescents in 59 countries: A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Government. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/criminal-law-sexual-offences-and-related-matters-amendment-act (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- South African Government. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/liquor-act (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Davids, E.L.; Kredo, T.; Gerritsen, A.A.; Mathews, C.; Slingers, N.; Nyirenda, M.; Abdullah, F. Adolescent girls and young women: Policy-to-implementation gaps for addressing sexual and reproductive health needs in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2020, 110, 855–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).