Self-Compassion as a Mediator of the Longitudinal Link Between Parent and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Depression and Adolescent Depression

1.2. Self-Compassion

1.3. Self-Compassion in Adolescence

1.4. Self-Compassion, Parental Depression, and Adolescent Depression

1.5. Gender and Age

1.6. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Brief Symptoms Inventory

2.3.2. Self-Compassion Scale

2.3.3. Children’s Depression Inventory

2.4. Data Analysis Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

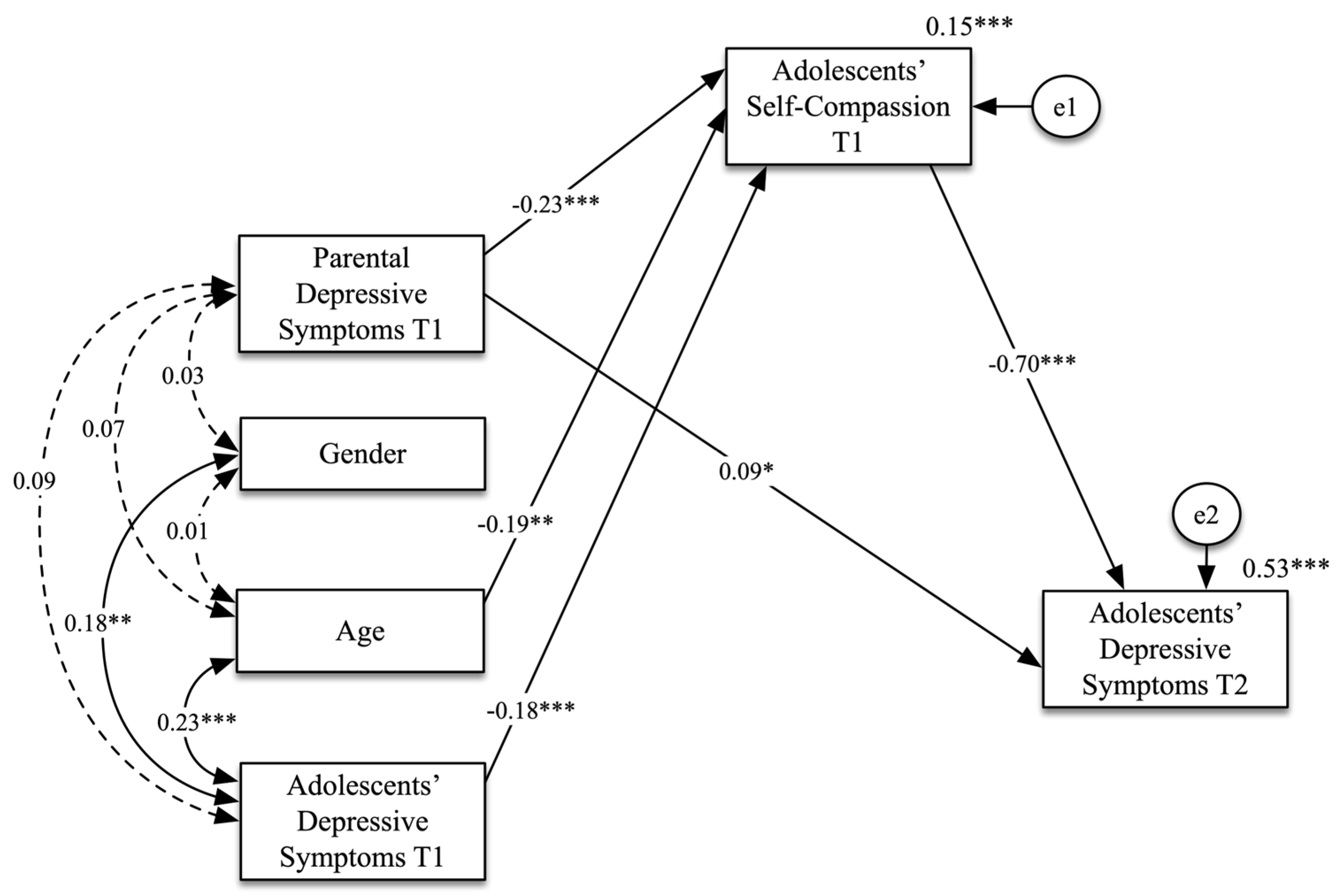

3.2. Path Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Adolescence, Depression, and Self-Compassion: Background and Aims

4.2. Main Findings

4.3. Strengths and Clinical and Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDS | Parental Depressive Symptoms |

| ADS | Adolescent Depressive Symptoms |

| SC | Self-Compassion |

| T1 | Time 1 |

| T2 | Time 2 |

| PASW | Predictive Analytics SoftWare |

| AMOS | Analysis of Moment Structures |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modelling |

References

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of 12 Mental Disorders in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Chen, H.; Liang, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Major Depressive Disorders in Adults Aged 60 Years and Older from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: Analyses from the Global Burden of Disease. J. Affect. Disorders. 2025, 374, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.L. Depression from Childhood through Adolescence: Risk Mechanisms across Multiple Systems and Levels of Analysis. Curr. Opin. Psychology 2015, 4, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global Prevalence of Depression and Elevated Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T.; Guedes, F.B.; Cerqueira, A.; Matos, M.G.; Equipa Aventura Social. A Saúde dos Adolescentes Portugueses em Contexto de Pandemia. Relatório do Estudo Health Behaviour in School Aged Children (HBSC) em 2022 [The Health of Portuguese Adolescents in the Context of the Pandemic. Report of the Health Behaviour in School Aged Children (HBSC) Study in 2022]. 2022. Available online: https://aventurasocial.com/dt_portfolios/a-saude-dos-adolescentes-portugueses-em-contexto-de-pandemia-dados-nacionais-2022 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Matos, M.G.; Equipa Aventura Social. A Saúde dos Adolescentes Portugueses Após a Recessão. Relatório do Estudo Health Behaviour in School Aged Children (HBSC) em 2018 [The Health of Portuguese Adolescents After the Recession. Report of the Study Health Behaviour in School Aged Children (HBSC) in 2018]. 2018. Available online: https://aventurasocial.com/dt_portfolios/estudo-health-behaviour-in-school-aged-children-hbsc-oms-internacional-2018 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Thapar, A.; Collishaw, S.; Pine, D.S.; Thapar, A.K. Depression in Adolescence. Lancet 2012, 379, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, L.P. The Adolescent Brain and Age-Related Behavioral Manifestations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000, 24, 417–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, N.B.; Sheeber, L.B. (Eds.) Adolescent Emotional Development and the Emergence of Depressive Disorders; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, L.; Härter, M.; Reese, C.; Kriston, L. Risk factors for chronic depression—A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 129, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs, M.; Obrosky, S.; George, C. The course of major depressive disorder from childhood to young adulthood: Recovery and recurrence in a longitudinal observational study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 203, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayborne, Z.M.; Varin, M.; Colman, I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, K.E.; Yap, M.B.; Pilkington, P.D.; Jorm, A.F. Risk and Protective Factors for Depression That Adolescents Can Modify: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 169, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnarson, E.O.; Craighead, W.E. Prevention of Depression among Icelandic Adolescents: A 12-Month Follow-Up. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Pineda, B.S.; Quero, S.; Karyotaki, E.; Struijs, S.Y.; Figueroa, C.A.; Llamas, J.A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Muñoz, R.F. Psychological Interventions to Prevent the Onset of Depressive Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, S.E.; Cox, G.R.; Witt, K.G.; Bir, J.J.; Merry, S.N. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Third-Wave CBT and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) Based Interventions for Preventing Depression in Children and Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD003380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.H.; Rouse, M.H.; Connell, A.M.; Broth, M.R.; Hall, C.M.; Heyward, D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburn, R.; Kazanas, S.A. Parental childhood rejection: An exploration of anxiety and depression in later life. Mod. Psychol. Stud. 2024, 30, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R.; Tambor, E.S.; Terdal, S.K.; Downs, D.L. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieb, R.; Isensee, B.; Höfler, M.; Wittchen, H.U. Parental Major Depression and the Risk of Depression and Other Mental Disorders in Offspring: A Prospective-Longitudinal Community Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2002, 59, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, M.T.; Murphy, E.; Posner, J.E.; Talati, A.; Weissman, M.M. Association of Multigenerational Family History of Depression with Lifetime Depressive and Other Psychiatric Disorders in Children: Results from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, M.M.; Wickramaratne, P.; Nomura, Y.; Warner, V.; Pilowsky, D.; Verdeli, H. Offspring of Depressed Parents: 20 Years Later. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Wickramaratne, P.; Gameroff, M.J.; Warner, V.; Pilowsky, D.; Kohad, R.G.; Verdeli, H.; Skipper, J.; Talati, A. Offspring of Depressed Parents: 30 Years Later. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J.; Ridder, E.M.; Beautrais, A.L. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, J.; Keiley, M.K.; Martin, N.C. Developmental trajectories of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Predictors of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P.M.; Rohde, P.; Klein, D.N.; Seeley, J.R. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder, I: Continuity into young adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 38, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, D.S.; Cohen, E.; Cohen, P.; Brook, J. Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: Moodiness or mood disorder? Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. An evolutionary approach to emotion in mental health with a focus on affiliative emotions. Emot. Rev. 2015, 7, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.C.; Dupasquier, J. Social safeness mediates the relationship between recalled parental warmth and the capacity for self-compassion and receiving compassion. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 89, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2003, 2, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D. Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Tóth-Király, I.; Yarnell, L.M.; Arimitsu, K.; Castilho, P.; Ghorbani, N.; Guo, H.X.; Hirsch, J.K.; Hupfeld, J.; Hutz, C.S.; et al. Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale in 20 diverse samples: Support for use of a total score and six subscale scores. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth-Király, I.; Neff, K.D. Is self-compassion universal? Support for the measurement invariance of the Self-Compassion Scale across populations. Assessment 2021, 28, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, M.; Xavier, A.; Castilho, P. Understanding self-compassion in adolescents: Validation study of the Self-Compassion Scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; Bluth, K.; Tóth-Király, I.; Davidson, O.; Knox, M.C.; Williamson, Z.; Costigan, A. Development and validation of the Self-Compassion Scale for Youth. J. Pers. Assess. 2020, 103, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, K.; Blanton, P.W. Mindfulness and self-compassion: Exploring pathways to adolescent emotional well-being. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, K.; Blanton, P.W. The influence of self-compassion on emotional well-being among early and older adolescent males and females. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K.D.; McGehee, P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self Identity 2010, 9, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Wekerle, C.; Schmuck, M.L.; Paglia-Boak, A. The linkages among childhood maltreatment, adolescent mental health, and self-compassion in child welfare adolescents. Child. Abus. Negl. 2011, 35, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettese, L.C.; Dyer, C.E.; Li, W.L.; Wekerle, C. Does self-compassion mitigate the association between childhood maltreatment and later emotion regulation difficulties? A preliminary investigation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011, 9, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.T.; Loflin, D.C.; Doucette, H. Adolescent self-compassion: Associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2015, 77, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Cunha, M.; Dinis, A. Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: The role of shame, self-criticism and fear of self-compassion. Child Youth Care Forum 2016, 45, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C.; Watson, L.; Williams, C.; Chan, S.W.Y. Social anxiety and self-compassion in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2018, 69, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, I.C.; Chan, S.W.Y.; MacBeth, A. Self-compassion and psychological distress in adolescents: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullmer, R.; Chung, J.; Samson, L.; Balanji, S.; Zaitsoff, S. A systematic review of the relation between self-compassion and depressive symptoms in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2019, 74, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, M.; Atalay, A.A. The relationship between perceived maternal parenting and psychological distress: Mediator role of self-compassion. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 2203–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, M.; Yuval, K.; Nitzan-Assayag, Y.; Bernstein, A. Self-compassion in recovery following potentially traumatic stress: Longitudinal study of at-risk youth. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolow, D.; Zuroff, D.C.; Young, J.F.; Karlin, R.A.; Abela, J.R. A prospective examination of self-compassion as a predictor of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Compassion and cruelty: A biopsychosocial approach. In Compassion: Conceptualisations, Research and Use in Psychotherapy; Gilbert, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 9–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P.; Irons, C. Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. In Adolescent Emotional Development and the Emergence of Depressive Disorders; Allen, N.B., Sheeber, L.B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M.; Gouveia, J.P.; Duarte, C. Constructing a self-protected against shame: The importance of warmth and safeness memories and feelings on the association between shame memories and depression. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2015, 15, 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P.; Procter, S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 13, 353–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankin, B.L.; Mermelstein, R.; Roesch, L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilt, L.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. The emergence of gender differences in depression in adolescence. In Handbook of Depression in Adolescents; Abela, J.R.Z., Hankin, B.L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos, N.L.; Leadbeater, B.J.; Barker, E.T. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A four-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004, 28, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Mendoza, R.; Paino, S.; Gillham, J.E. A two-year longitudinal study of gender differences in responses to positive affect and depressive symptoms during middle adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2017, 56, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, J. Depression in children and adolescents: Linking risk research and prevention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31 (Suppl. S1), S104–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezulis, A.; Salk, R.H.; Hyde, J.S.; Priess-Groben, H.A.; Simonson, J.L. Affective, Biological, and Cognitive Predictors of Depressive Symptom Trajectories in Adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chad-Friedman, E.; Jordan, L.S.; Chad-Friedman, S.; Lemay, E.; Olino, T.; Klein, D.N.; Dougherty, L.R. Parent and child depressive symptoms and authoritarian parenting: Reciprocal relations from early childhood through adolescence. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 12, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joormann, J.; Eugene, F.; Gotlib, I.H. Parental depression: Impact on offspring and mechanisms underlying transmission of risk. In Handbook of Depression in Adolescents; Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Hilt, L.M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 441–472. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.C. Understanding and addressing youth depression: Risk factors, resources, and promoting mental health and well-being. Psychology 2023, 14, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, O.; Mendes, J.F.; Templeton, P. Biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression: A review of recent literature. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuenschwander, R.; von Gunten, F.O. Self-compassion in children and adolescents: A systematic review of empirical studies through a developmental lens. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 755–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavarro, M.C. Inventário de Sintomas Psicopatológicos: BSI. In Testes e Provas Psicológicas em Portugal; Simões, M.R., Gonçalves, M., Almeida, L.S., Eds.; SHO/APPORT: Braga, Portugal, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Melisaratos, N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychol. Med. 1983, 13, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutsiou-Ladd, A.; Panayiotou, G.; Kokkinos, C.M. A review of the factorial structure of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Greek evidence. Int. J. Test. 2008, 8, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, N.; Forns, M.; Peró, M. Dimensional structure of the Brief Symptom Inventory with Spanish college students. Psicothema 2007, 19, 634–639. [Google Scholar]

- Marujo, H.Á. Síndromas Depressivos na Infância e na Adolescência. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, M. Children’s Depression Inventory; Multi-Health Systems, Inc.: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jelínek, M.; Květon, P.; Burešová, I.; Klimusová, H. Measuring depression in adolescence: Evaluation of a hierarchical factor model of the Children’s Depression Inventory and measurement invariance across boys and girls. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B.; Weisz, J.R.; Politano, M.; Carey, M.; Nelson, W.M.; Finch, A.J. Developmental differences in the factor structure of the Children’s Depression Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1991, 3, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smucker, M.R.; Craighead, W.E.; Craighead, L.W.; Green, B.J. Normative and reliability data for the Children’s Depression Inventory. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1986, 14, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bento, C.; Pereira, A.T.; Marques, M.; Saraiva, J.; Macedo, A. 1765–Further validation of the Children’s Depression Inventory in a Portuguese adolescents sample. Eur. Psychiatry 2013, 28 (Suppl. S1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, B.; Collishaw, S.; Stringaris, A. Depression in childhood and adolescence. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P.; Perris, C. Early experiences and subsequent psychosocial adaptation: An introduction. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2000, 7, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammen, C. Context of stress in families of children with depressed parents. In Children of Depressed Parents: Mechanisms of Risk and Implications for Treatment; Goodman, S.H., Gotlib, I.H., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Abela, J.R.; Hankin, B.L. Rumination as a vulnerability factor to depression during the transition from early to middle adolescence: A multiwave longitudinal study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011, 120, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.; Matos, M.; Faria, D.; Zagalo, S. Shame memories and psychopathology in adolescence: The mediator effect of shame. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2012, 12, 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, G.; Blatt, S.J.; Zuroff, D.C.; Kuperminc, G.P.; Leadbeater, B.J. Reciprocal relations between depressive symptoms and self-criticism (but not dependency) among early adolescent girls (but not boys). Cogn. Ther. Res. 2004, 28, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, F.; Searle, A.; Sawyer, M. Identifying and implementing prevention programmes for childhood mental health problems. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 43, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluth, K.; Gaylord, S.A.; Campo, R.A.; Mullarkey, M.C.; Hobbs, L. Making friends with yourself: A mixed methods pilot study of a mindful self-compassion program for adolescents. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galla, B.M. Within-person changes in mindfulness and self-compassion predict enhanced emotional well-being in healthy, but stressed adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K.D.; Germer, C.K. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodfin, V.; Molde, H.; Dundas, I.; Binder, P.-E. A randomized control trial of a brief self-compassion intervention for perfectionism, anxiety, depression, and body image. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 751294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Federation for Mental Health. Depression: A global crisis. World Fed. Ment. Health 2012. Available online: http://www.wfmh.org/2012DOCS/WMHDay%202012%20SMALL%20FILE%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2025).[Green Version]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (T1) | 13.67 | 1.38 | - | |||||

| 2. Adolescent depressive symptoms (T1) | 10.32 | 6.08 | 0.20 ** | - | ||||

| 3. Parental depressive symptoms (T1) | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.13 ** | - | |||

| 4. Self-compassion (T1) | 77.35 | 18.82 | −0.23 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.22 ** | - | ||

| 5. Self-compassion (T2) | 72.66 | 12.66 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.04 | - | |

| 6. Adolescent depressive symptoms (T2) | 15.62 | 9.97 | 0.23 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.73 ** | 0.15 * | - |

| 7. Parental depressive symptoms (T2) | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.83 ** | −0.14 * | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Path | b | SE | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | |||||

| Parental depressive symptoms (T1) → Adolescent depressive symptoms (T2) | 1.24 | 0.53 | 2.34 | 0.019 | [0.168, 2.248] |

| Parental depressive symptoms (T1) → Adolescent self-compassion (T1) | −5.79 | 1.32 | −4.40 | <0.001 | [−8.314, −3.137] |

| Adolescent self-compassion (T1) → Adolescent depressive symptoms (T2) | −0.371 | 0.02 | −17.43 | <0.001 | [−0.413, −0.329] |

| Age → Adolescent self-compassion (T1) | −2.55 | 0.74 | −3.45 | <0.001 | [−4.041, −1.115] |

| Adolescent depressive symptoms (T1) → Adolescent self-compassion (T1) | −0.54 | 0.17 | −3.24 | 0.001 | [−0.872, −0.212] |

| Indirect effects | |||||

| Parental depressive symptoms (T1) → Adolescent self-compassion (T1) → Adolescent depressive symptoms (T2) | 2.15 | - | - | 0.001 | [0.087, 0.229] |

| Age → Adolescent self-compassion (T1) → Adolescent depressive symptoms (T2) | 0.95 | - | - | 0.001 | [0.055, 0.208] |

| Adolescent depressive symptoms (T1) → Adolescent self-compassion (T1) → Adolescent depressive symptoms (T2) | 0.20 | - | - | 0.002 | [0.049, 0.199] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cherpe, S.; Cunha, M.; Xavier, A.M.; Matos, A.P.; Arnarson, E.Ö.; Craighead, W.E.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Self-Compassion as a Mediator of the Longitudinal Link Between Parent and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms. Adolescents 2025, 5, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030045

Cherpe S, Cunha M, Xavier AM, Matos AP, Arnarson EÖ, Craighead WE, Pinto-Gouveia J. Self-Compassion as a Mediator of the Longitudinal Link Between Parent and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms. Adolescents. 2025; 5(3):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030045

Chicago/Turabian StyleCherpe, Sónia, Marina Cunha, Ana Maria Xavier, Ana Paula Matos, Eiríkur Örn Arnarson, W. Edward Craighead, and José Pinto-Gouveia. 2025. "Self-Compassion as a Mediator of the Longitudinal Link Between Parent and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms" Adolescents 5, no. 3: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030045

APA StyleCherpe, S., Cunha, M., Xavier, A. M., Matos, A. P., Arnarson, E. Ö., Craighead, W. E., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2025). Self-Compassion as a Mediator of the Longitudinal Link Between Parent and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms. Adolescents, 5(3), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5030045